Abstract

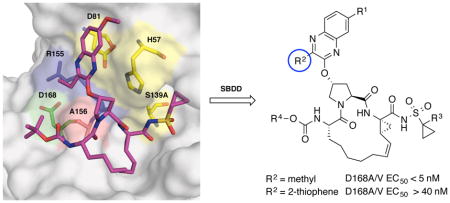

A substrate envelope-guided design strategy is reported for improving the resistance profile of HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors. Analogues of 5172-mcP1P3 were designed by incorporating diverse quinoxalines at the P2 position that predominantly interact with the invariant catalytic triad of the protease. Exploration of structure-activity relationships showed that inhibitors with small hydrophobic substituents at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline maintain better potency against drug resistant variants, likely due to reduced interactions with residues in the S2 subsite. In contrast, inhibitors with larger groups at this position were highly susceptible to mutations at Arg155, Ala156 and Asp168. Excitingly, several inhibitors exhibited exceptional potency profiles with EC50 values ≤ 5 nM against major drug resistant HCV variants. These findings support that inhibitors designed to interact with evolutionarily constrained regions of the protease, while avoiding interactions with residues not essential for substrate recognition, are less likely to be susceptible to drug resistance.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infects over 130 million people globally and is the leading cause of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.1 HCV is known as a “silent killer” as a majority of affected patients remain unaware of their infection, and over time the acute infection progresses to chronic liver disease.2 The rate of cirrhosis is estimated to increase from 16% to 32% by the year 2020 due to the high number of untreated patients.3 Thus, there is an urgent need to ensure that patients infected with HCV receive proper treatment. However, HCV infection is difficult to treat, as the virus is genetically diverse with six known genotypes (genotype 1–6), each of which is further sub-divided into numerous subtypes.4 Genotype 1 (GT1) and genotype 3 (GT3) are the most prevalent accounting for 46% and 30% of global infections, respectively.4,5 Therapeutic regimen and viral response are largely genotype dependent with most treatments being efficacious only against GT1.6

The recent advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) targeting essential viral proteins NS3/4A, NS5A, and NS5B has remarkably improved therapeutic options and treatment outcomes for HCV infected patients.6,7 Four new all-oral combination treatments have been approved by the US FDA: (1) sofosbuvir/ledipasvir,8 (2) ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir,9 (3) elbasvir/grazoprevir,10 and (4) sofosbuvir/velpatasvir.11 The DAA-based therapies are highly effective against GT1 with sustained virological response (SVR) rates greater than 90%.6,7 However, most of the FDA approved treatments and those in clinical development are not efficacious against other genotypes, especially GT3.7 Moreover, except for sofosbuvir, all current DAAs are susceptible to drug resistance.12 Therefore, more robust DAAs need to be developed with higher barriers to drug resistance and a broad spectrum of activity against different HCV genotypes.

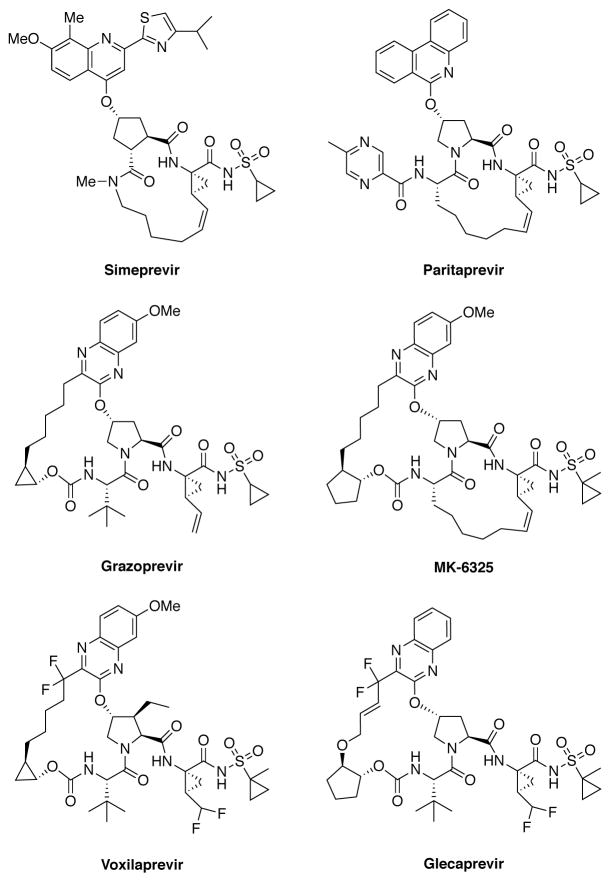

The HCV NS3/4A protease is a major therapeutic target for the development of pan-genotypic HCV inhibitors.13,14 The NS3/4A protease inhibitors (PIs) telaprevir15 and boceprevir16 were the first DAAs approved for the treatment of HCV GT1 infection in combination therapy with pegylated-interferon and ribavirin.17,18 Three recently approved PIs, simeprevir,19 paritaprevir20 and grazoprevir,21 (Figure 1) are integral components of various combination therapies currently used as the standard of care for HCV infected patients.6,7,14 Two other NS3/4A PIs, asunaprevir22 and vaniprevir,23 have been approved in Japan. In addition, a number of next generation NS3/4A PIs are in clinical development including glecaprevir24 and voxilaprevir25 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors. Simeprevir, paritaprevir and grazoprevir are approved by the FDA; voxilaprevir and glecaprevir are in clinical development.

All NS3/4A PIs share a common peptidomimetic scaffold and are either linear or macrocyclic; the macrocycle is located either between P1–P3 or P2–P4 moieties.14 In addition, these inhibitors contain a large heterocyclic moiety attached to the P2 proline, which significantly improves inhibitor potency against wild-type (WT) NS3/4A protease.26,27 However, all NS3/4A PIs are susceptible to drug resistance, especially due to single site mutations at protease residues Arg155, Ala156 and Asp168.28,29 Notably, D168A/V mutations are present in nearly all patients who fail treatment with PIs.12 Moreover, natural polymorphisms at this position are responsible for significantly reduced inhibitor potency against GT3.30 We previously determined the molecular mechanisms of drug resistance due to single site mutations by solving high-resolution crystal structures of PIs bound to WT and mutant proteases.31–34 These crystal structures revealed that the large heterocyclic P2 moieties of PIs bind outside the substrate binding region, defined as the substrate envelope, and make extensive interactions with residues Arg155, Ala156 and Asp168.32,33 The inhibitor P2 moiety induces an extended S2 subsite by forcing the Arg155 side chain to rotate nearly 180° relative to its conformation in substrate complexes.31 This altered Arg155 conformation is stabilized by electrostatic interactions with Asp168, providing additional hydrophobic surface that is critical for efficient inhibitor binding. Disruption of electrostatic interactions between Arg155 and Asp168 due to mutations underlies drug resistance against NS3/4A PIs.31–33,35 Moreover, we have shown that structural differences at the P2 moiety largely determine the resistance profile of these inhibitors.36

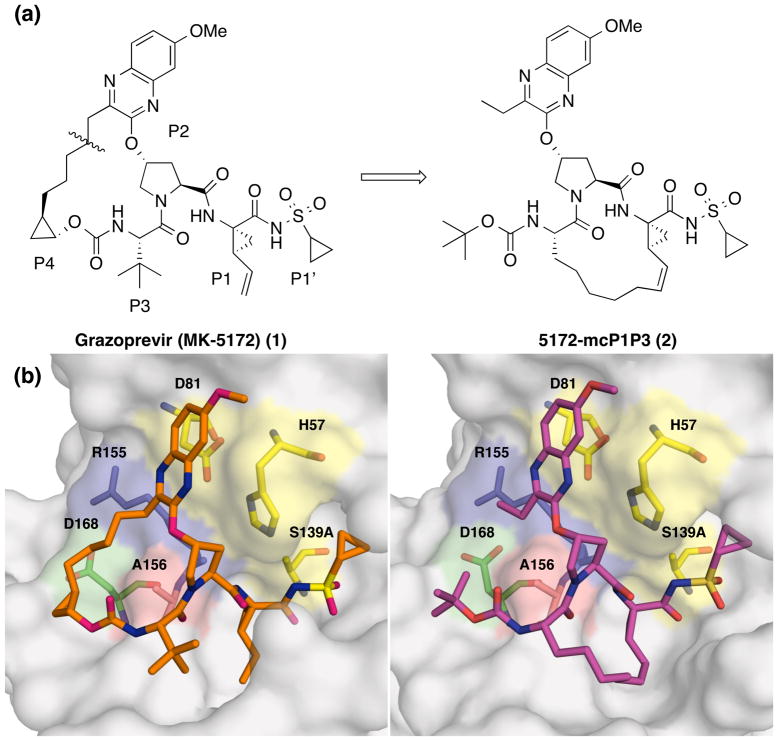

Grazoprevir (MK-5172, 1), one of the most potent HCV NS3/4A PIs, has a unique binding mode where the P2 quinoxaline moiety interacts with residues of the catalytic triad, avoiding direct interactions with Arg155 and Asp168 (Figure 2).32 As a result, 1 has an excellent potency profile across different genotypes and relatively low susceptibility to drug resistance due to mutations at Arg155 and Asp168.21,37 However, 1 is highly susceptible to mutations at Ala156, mainly due to steric clashes of larger side chains with the P2–P4 macrocycle. We have shown that the P1–P3 macrocyclic analogue 5172-mcP1P3 (2) avoids this steric clash while still maintaining the unique binding mode of 1 (Figure 2).38 Compound 2, though slightly less potent than 1 against WT HCV, has an excellent potency profile with EC50 values in the single digit nanomolar range against drug resistant variants including A156T. Similar to 1, the P2 quinoxaline moiety in 2 stacks against the catalytic residues His57 and Asp81 and largely avoids direct interactions with residues around the S2 subsite.38 But unlike 1, the flexible P2 quinoxaline moiety in 2 better accommodates mutations at Ala156, resulting in an overall improved resistance profile.36,38 Thus, the P1–P3 macrocyclic analogue 2 is a promising lead compound for structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies to further improve potency against drug resistant variants and other genotypes.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures and binding modes of grazoprevir (1) and analogue 2. (a) Compound 2 was designed by replacing the P2–P4 macrocycle in 1 with a P1–P3 macrocycle. (b) The binding conformation of 1 (PDB code: 3SUD) and 2 (PDB code: 5EPN) in the active site of wild-type NS3/4A protease. Compound 2 maintains the unique binding mode of 1 whereby the P2 quinoxaline makes strong interactions with the catalytic residues avoiding contacts with known drug resistance residues. The catalytic triad is highlighted in yellow and drug resistance residues Arg155, Ala156, and Asp168 are shown in blue, red and green, respectively. The canonical nomenclature for drug moiety positioning is indicated using grazoprevir.

The substrate envelope model provides a rational approach to design NS3/4A PIs with improved resistance profiles by exploiting interactions with the protease residues essential for function and avoiding direct contacts with residues that can mutate to confer drug resistance.39–41 Another approach applied to design PIs with improved resistant profiles involves incorporation of conformational flexibility that can allow the inhibitor to adapt to structural changes in the protease active site due to mutations.35 Here, we describe a structure-guided strategy that combines these two approaches and, together with our understanding of the mechanisms of drug resistance, led to the design of NS3/4A PIs with exceptional potency profiles against major drug resistant HCV variants. Based on the lead compound 2, a series of analogues were designed and synthesized with diverse substituents at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline moiety. Investigation of SARs identified P2 quinoxaline derivatives that predominantly interact with the invariant catalytic triad and avoid contacts with the S2 subsite residues. The results indicate that combining the substrate envelope model with optimal conformational flexibility provides a general strategy for the rational design of NS3/4A PIs with improved resistance profiles.

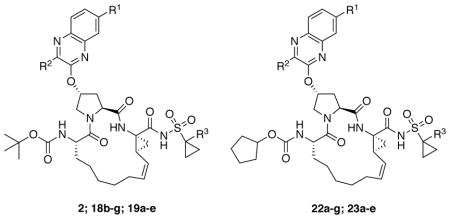

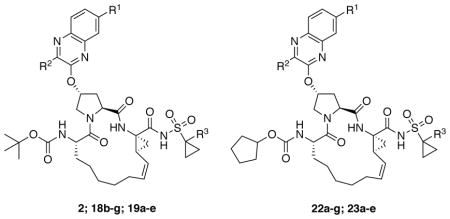

CHEMISTRY

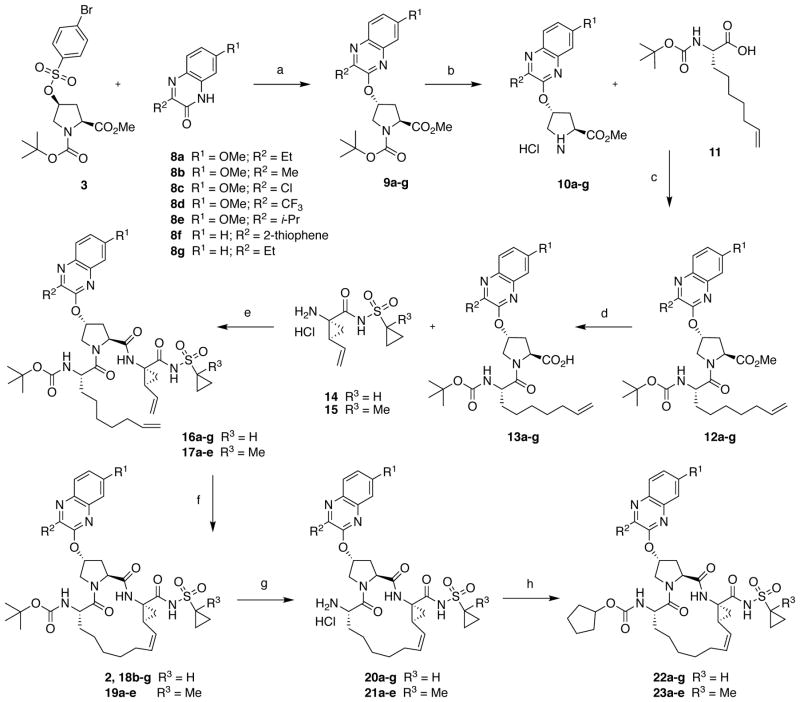

The NS3/4A PIs with diverse P2 quinoxaline moieties were synthesized using the reaction sequence outlined in Scheme 1. A Cs2CO3-mediated SN2 reaction of 3-substituted quinoxalin-2-ones 8a-g with the activated proline derivative 3 provided the key P2 intermediates 9a-g in 75–90% yield. The alternate SNAr reaction between activated quinoxaline derivatives and Boc-protected hydroxy-proline resulted in lower yields, and purification of the resulting P2 acid products was significantly more challenging. The 3-substituted 7-methoxy-quinoxalin-2-ones 8ab and 8d-e were prepared by condensation reactions of 4-methoxybenzene-1,2-diamine with the corresponding ethyl glyoxylates (see Supporting Information for details). The 3-chloro-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-one 8c was prepared according to a reported method.21

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors. Reagents and conditions: (a) Cs2CO3, NMP, 55 °C, 6 h; (b) 4 N HCl in dioxane, CH2Cl2, RT, 3 h; (c) HATU, DIEA, DMF, RT, 4 h; (d) LiOH.H2O, THF, H2O, RT, 24 h; (e) HATU, DIEA, DMF, RT, 2 h; (f) Zhan 1B catalyst, 1,2-DCE, 70 °C, 6 h; (g) 4 N HCl, dioxane, RT, 3 h; (h) N-(cyclopentyloxycarbonyloxy)-succinimide, DIEA, CH3CN, RT, 36 h.

The P1–P3 macrocyclic PIs were assembled from the P2 intermediates 9a-g using a sequence of deprotection and peptide coupling steps followed by the ring-closing metathesis (RCM) reaction (Method A). Removal of the Boc group in 9a-g using 4 N HCl provided the amine salts 10a-g, which were coupled with the amino acid 11 in the presence of HATU and DIEA to yield the P2–P3 ester intermediates 12a-g. Hydrolysis of these esters with LiOH and reaction of the resulting carboxylic acids 13a-g with the P1–P1′ fragments 1442 and 1543 under HATU/DIEA coupling conditions provided the bis-olefin intermediates 16a-g and 17a-e. Finally, cyclization of the bis-olefin intermediates was accomplished using a highly efficient RCM catalyst Zhan 1B, and provided the inhibitors 18b-g and 19a-e in 45–80% yield. Interestingly, RCM reactions of bis-olefins 17a-e bearing the 1-methylcyclopropylsulfonamide provided higher yield than the corresponding cyclopropylsulfonamide analogues 16a-g. Finally, removal of the Boc group and reaction of the resulting amine salts 20a-g and 21a-e with the N-(cyclopentyloxycarbonyloxy)-succinimide in the presence of DIEA afforded the inhibitors 22a-g and 23a-e with the N-terminal cyclopentyl P4 moiety.

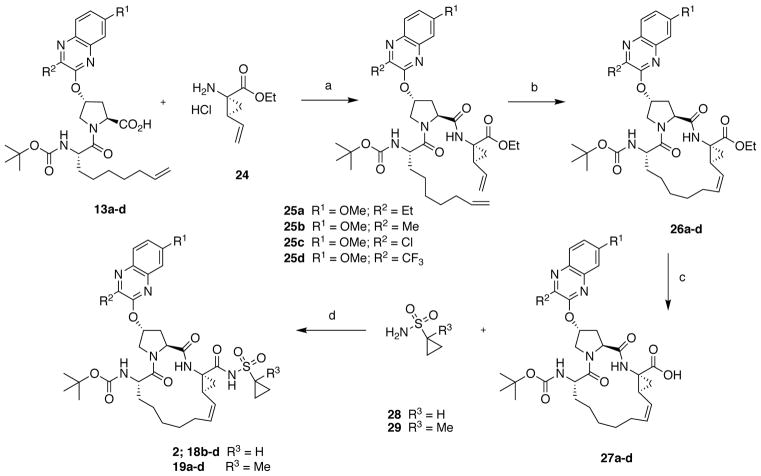

A subset of inhibitors was synthesized using an alternate reaction sequence that allowed late-stage modification at both the P1′ and P4 positions as illustrated in Scheme 2 (Method B). The P2–P3 acid intermediates 13a-d were reacted with the commercially available amine salt 24 under HATU/DIEA coupling conditions to afford the bis-olefin intermediates 25a-d. RCM reaction in the presence of Zhan 1B catalyst provided the macrocyclic intermediates 26a-d in 75–90% yield, which was better than that obtained in the presence of the P1′ acylsulfonamide. The P1–P3 macrocyclic core intermediates 26a-d can be modified in either direction after removing the C- or N-terminal protecting groups. Thus, hydrolysis of the C-terminal ethyl ester with LiOH provided the acids 27a-d, which were then reacted with either cyclopropylsulfonamide 28 or 1-methylcyclopropylsulfonamide 29 in the presence of CDI and DBU to afford the final inhibitors 18b-d and 19a-d. The N-terminal tert-butyl capping group was replaced with the cyclopentyl moiety as described earlier to provide the target inhibitors 22a-d and 23a-d.

Scheme 2.

Alternate synthesis of HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors. Reagents and conditions: (a) HATU, DIEA, DMF, RT, 2 h; (b) Zhan 1B catalyst, 1,2-DCE, 70 °C, 5 h; (c) LiOH.H2O, THF, MeOH, H2O, RT, 24 h; (d) CDI, THF, DBU, reflux, 1.5 h, RT, 36 h.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Our goal was to develop a structure-guided design strategy to improve the resistance profile of HCV NS3/4A PIs based on the substrate envelope model.39,40 Compound 2 is an attractive scaffold for exploring this strategy due to the unique structural features: (1) the P2 quinoxaline moiety that predominantly interacts with the highly conserved catalytic residues Asp81 and His57 and (2) the conformational flexibility that allows the inhibitor to efficiently accommodate structural changes in the S2 subsite due to resistance mutations. Despite these promising features, optimization of substituents at the P2 quinoxaline and the N-terminal capping may be key to discovering analogues with improved potency and resistance profiles. Therefore, efforts were focused on exploration of SARs at the P2 quinoxaline moiety in 2, specifically substituting the ethyl group at the 3-position that directly interacts with protease S2 subsite residues Arg155 and Ala156. The SAR strategy was based on insights from detailed structural analysis of 1 and 2 bound to wild-type NS3/4A protease and drug resistant variants.32,38 Based on these insights, we hypothesized that small hydrophobic groups at the 3-position of the quinoxaline would be preferred for retaining inhibitor potency against drug resistant variants, but larger groups that make extensive interactions with Arg155, Ala156 and Asp168 would result in inhibitors highly susceptible to mutations at these positions. To test this hypothesis, a series of inhibitors with diverse substituents at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline were designed and synthesized.

The potency and resistance profiles of NS3/4A PIs were assessed using biochemical and replicon assays. The enzyme inhibition constants (Ki) were determined against wild-type GT1a NS3/4A protease, drug-resistant variant D168A, and GT3a NS3/4A protease (Table 1). The cellular antiviral potencies (EC50) were determined using replicon-based antiviral assays against wild-type HCV and drug-resistant variants R155K, A156T, D168A, and D168V (Table 2). Grazoprevir (GZR, 1) was used as a control in all assays. The observed antiviral potencies are generally higher than protease inhibitory potencies, likely because biochemical assays were performed using the protease domain alone rather then the full-length NS3/4A.

Table 1.

Inhibitory activity against wild-type NS3/4A protease and drug resistant variants

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Inhibitor | R1 | R2 | R3 | Ki (nM) | ||

|

| ||||||

| GT1a WT NS3/4A Protease | GT1a D168A NS3/4A Protease | GT3a NS3/4A Protease | ||||

| 2 | OMe | Et | H | 3.29 ± 0.52 | 82.4 ± 4.4 | 204 ± 19 |

| 19a | OMe | Et | Me | 1.82 ± 0.38 | 55.2 ± 5.3 | 171 ± 23 |

| 22a | OMe | Et | H | 1.24 ± 0.14 | 52.3 ± 3.2 | 211 ± 18 |

| 23a | OMe | Et | Me | 1.37 ± 0.34 | 55.2 ± 5.3 | 186 ± 30 |

|

| ||||||

| 18b | OMe | Me | H | 3.40 ± 0.47 | 50.9 ± 3.7 | 152 ± 18 |

| 19b | OMe | Me | Me | 3.60 ± 0.44 | 52.0 ± 2.4 | 119 ± 18 |

| 22b | OMe | Me | H | 0.93 ± 0.15 | 31.9 ± 2.5 | 147 ± 20 |

| 23b | OMe | Me | Me | 1.13 ± 0.22 | 36.3 ± 1.8 | 121 ± 16 |

|

| ||||||

| 18c | OMe | Cl | H | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 39.8 ± 3.4 | 67.5 ± 8.0 |

| 19c | OMe | Cl | Me | 1.11 ± 0.38 | 77.7 ± 6.1 | 53.6 ± 5.9 |

| 22c | OMe | Cl | H | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 30.6 ± 2.6 | 85.6 ± 11 |

| 23c | OMe | Cl | Me | 0.44 ± 0.15 | 25.7 ± 1.8 | 61.0 ± 12 |

|

| ||||||

| 18d | OMe | CF3 | H | 13.3 ± 3.9 | 157 ± 12 | 344 ± 141 |

| 19d | OMe | CF3 | Me | 5.77 ± 1.78 | 118 ± 13 | 231 ± 74 |

| 22d | OMe | CF3 | H | 7.55 ± 2.39 | 115 ± 12 | 757 ± 334 |

| 23d | OMe | CF3 | Me | 8.14 ± 2.37 | 110 ± 14 | 433 ± 206 |

|

| ||||||

| 18e | OMe | i-Pr | H | 4.27 ± 1.34 | 239 ± 20 | NT |

| 19e | OMe | i-Pr | Me | 0.58 ± 0.08 | 211 ± 19 | NT |

| 22e | OMe | i-Pr | H | 1.44 ± 0.46 | 161 ± 11 | NT |

| 23e | OMe | i-Pr | Me | 1.34 ± 0.48 | 156 ± 17 | NT |

|

| ||||||

| 18f | H | 2-thiophene | H | 1.03 ± 0.13 | 1823 ± 347 | NT |

| 22f | H | 2-thiophene | H | 1.59 ± 0.56 | 900 ± 81 | NT |

|

| ||||||

| 18g | H | Et | H | 7.18 ± 1.02 | 190 ± 13 | NT |

| 22g | H | Et | H | 1.99 ± 0.48 | 107 ± 7.0 | NT |

|

| ||||||

| GZR (1) | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 49.1 ± 1.6 | 30.3 ± 1.9 | |||

NT: not tested

Table 2.

Antiviral activity against wild-type HCV and drug resistant variants.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Inhibitor | R1 | R2 | R3 | Replicon EC50 (nM) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| WT | R155K | A156T | D168A | D168V | ||||

| 2 | OMe | Et | H | 0.33 | 1.75 | 9.65 | 6.31 | 9.10 |

| 19a | OMe | Et | Me | 0.43 | 1.80 | 4.52 | 4.97 | 6.42 |

| 22a | OMe | Et | H | 0.14 | 2.08 | 11.8 | 3.60 | 11.9 |

| 23a | OMe | Et | Me | 0.16 | 2.07 | 10.6 | 3.45 | 7.08 |

|

| ||||||||

| 18b | OMe | Me | H | 0.39 | 1.17 | 5.95 | 4.24 | 3.17 |

| 19b | OMe | Me | Me | 0.30 | 0.80 | 1.57 | 2.37 | 1.60 |

| 22b | OMe | Me | H | 0.11 | 0.89 | 2.88 | 2.63 | 4.32 |

| 23b | OMe | Me | Me | 0.13 | 1.09 | 3.99 | 2.16 | 2.85 |

|

| ||||||||

| 18c | OMe | Cl | H | 0.16 | 0.44 | 16.2 | 1.42 | 0.73 |

| 19c | OMe | Cl | Me | 0.18 | 0.40 | 8.86 | 1.07 | 0.49 |

| 22c | OMe | Cl | H | 0.15 | 0.59 | 3.55 | 1.32 | 1.55 |

| 23c | OMe | Cl | Me | 0.15 | 0.56 | 4.32 | 0.97 | 1.09 |

|

| ||||||||

| 18d | OMe | CF3 | H | 1.98 | 3.45 | 36.2 | 16.8 | 17.1 |

| 19d | OMe | CF3 | Me | 1.52 | 2.30 | 20.5 | 8.64 | 8.31 |

| 22d | OMe | CF3 | H | 4.86 | 7.97 | 117 | 15.1 | 24.0 |

| 23d | OMe | CF3 | Me | 4.04 | 6.90 | 75.9 | 8.46 | 11.4 |

|

| ||||||||

| 18e | OMe | i-Pr | H | 1.43 | 5.02 | 25.7 | 15.3 | 23.7 |

| 19e | OMe | i-Pr | Me | 1.86 | 4.14 | 21.2 | 11.9 | 18.1 |

| 22e | OMe | i-Pr | H | 0.48 | 7.63 | 32.1 | 7.96 | 30.1 |

| 23e | OMe | i-Pr | Me | 0.59 | 6.83 | 27.6 | 7.91 | 18.2 |

|

| ||||||||

| 18f | H | 2-thiophene | H | 0.98 | 21.7 | 256 | 111 | 193 |

| 22f | H | 2-thiophene | H | 0.40 | 19.2 | 183 | 42.2 | 70.0 |

|

| ||||||||

| 18g | H | Et | H | 0.46 | 1.81 | 10.6 | 8.55 | 14.0 |

| 22g | H | Et | H | 0.24 | 4.28 | 24.6 | 7.50 | 19.3 |

|

| ||||||||

| GZR (1) | 0.14 | 1.89 | 238 | 9.69 | 5.41 | |||

Compound 1 showed sub-nanomolar inhibitory potency against WT NS3/4A protease and maintained nanomolar activity against drug resistant variant D168A and GT3a protease. Similarly, in replicon assays 1 exhibited an excellent potency profile with sub-nanomolar activity against WT HCV (EC50 = 0.14 nM) and low nanomolar activity against drug resistant variants R155K, D168A, and D168V. However, in line with previous reports,36 1 was highly susceptible to the A156T mutation (EC50 = 238 nM), losing over 1000-fold potency against this variant. Compared to 1, the P1–P3 macrocyclic analogue 2 exhibited lower inhibitory potency against WT protease and the D168A variant. Also, the inhibitory activity of 2 against the GT3a protease was considerably lower than that of 1. However, as we have previously shown,36 2 displayed a superior potency profile in replicon assays with sub-nanomolar activity against WT HCV (EC50 = 0.33 nM) and maintained single digit nanomolar potency against all drug-resistant variants tested. Notably, unlike 1, compound 2 maintained low nanomolar potency against the A156T variant (EC50 = 9.65 nM). Thus, with an improved resistance profile compared to 1, the P1–P3 macrocyclic analogue 2 is an attractive lead compound for further optimization.

Modifications of P1′ and P4 Capping Groups

Initial SAR efforts to optimize lead compound 2 focused on exploring changes at the P1′ position and N-terminal capping group. Recent SAR studies of diverse NS3/4A PIs indicate that replacement of the cyclopropylsulfonamide moiety at the P1′ position with a slightly more hydrophobic 1-methylcyclopropylsulfonamide improves inhibitor potency in replicon assays.43,44 Moreover, changes at the P4 position have been shown to significantly affect inhibitor potency against drug resistant variants, as these groups bind in close proximity to the pivotal drug resistance site Asp168.45 For carbamate-linked P4 capping groups, generally bulky hydrophobic moieties are preferred but the size of the group appears to be dependent on the heterocyclic moiety present at the P2 position.35

First, replacing the cyclopropylsulfonamide at the P1′ position in 2 with 1-methylcyclopropylsulfonamide provided the analogue 19a. Compared to the parent compound 2, 19a showed slightly better Ki values against WT, D168A and GT3a proteases and exhibited similar or slightly better antiviral potency against WT and drug resistant variants. Next, the tert-butyl P4 capping group in both 2 and 19a was replaced with a larger cyclopentyl moiety, resulting in analogues 22a and 23a. Unlike the change at the P1′ position, the P4 cyclopentyl modification provided mixed results. Compound 22a afforded a 2-fold increase in potency than 2 in biochemical assays against WT protease and a slight improvement against the D168A variant, but was equipotent to 2 against GT3a protease. Similarly, in replicon assays 22a exhibited 2-fold enhanced potency against WT HCV and D168A variant, but showed similar potency as 2 against the R155K and D168V variants. Compound 23a, with a 1-methylcyclopropylsulfonamide moiety at the P1′ position and a cyclopentyl group at the P4 position, exhibited potency profile largely similar to 22a. Surprisingly, a slight loss in potency was observed against the A156T variant for compounds with a cyclopentyl versus tert-butyl capping group. Overall, these minor modifications at the P1′ and N-terminal capping regions of inhibitor 2 were tolerated and provided analogues with improved potency profiles.

SAR Exploration of P2 Quinoxaline

Next, SARs at the P2 quinoxaline in compound 2 were explored. Efforts mainly focused on replacing the 3-position ethyl group with diverse functional groups with respect to size and electronic properties. Replacement of the ethyl group in 2 with a smaller methyl group provided analogue 18b. As expected, reducing the size of the hydrophobic group at this position resulted in improved potency profile. Compound 18b showed slightly enhanced potency against drug resistant variants in biochemical and antiviral assays, with a notable ~2-fold improvement against the D168V variant (EC50 = 3.17 nM). The introduction of 1-methylcyclopropylsulfonamide moiety at the P1′ position afforded inhibitor 19b with protease inhibitory activity comparable to the parent compound 18b. However, similar to the 3-ethylquinoxaline analogue (19a), compound 19b demonstrated significant gain in potency in replicon assays. In fact, compared to 2, 19b exhibited 2- to 6-fold enhancement in potency against drug resistant variants R155K (EC50 = 0.80 nM), A156T (EC50 = 1.57 nM), D168A (EC50 = 2.37 nM), and D168V (EC50 = 1.6 nM). Replacement of the tert-butyl P4 capping in 18b and 19b with a cyclopentyl group, providing 22b and 23b, resulted in an increase in WT and D168A inhibitory activity as well as 2- to 3-fold increase in WT replicon potency. Unlike the corresponding 3-ethylquinoxaline analogues (22a and 23a), the 3-methyquinoxaline compounds 22b and 23b maintained the excellent potency profile observed for the corresponding tert-butyl analogues. Remarkably, with the exception of 18b (A156T EC50 = 5.95 nM), all compounds in the 3-methylquinoxaline series display exceptional potency profiles with EC50 values below 5 nM against WT and clinically relevant drug resistant variants.

To gain insights into the excellent potency profile observed for the 3-methyquinoxaline series, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of inhibitor 19b in complex with the WT NS3/4A protease at a resolution of 1.8 Å (Figure 3, Table S3, PDB code: 5VOJ). The WT-19b complex structure was compared with the previously reported structures of compound 2 in complex with WT protease and the A156T variant (PDB codes: 5EPN and 5EPY).38 The two WT structures overlap very well, with only minor differences in the S1 and S2 subsites because of modifications in the inhibitor structure. In the WT-2 crystal structure, the 3-ethyl group at the P2 quinoxaline makes hydrophobic interactions with the hydrocarbon portion of the Arg155 side-chain, while the methylene portion of this group interacts with the side-chain of Ala156. The smaller methyl group at this position in the WT-19b structure maintains hydrophobic interactions with Ala156, while minimizing chances of steric clash with a larger side-chain, such as in A156T.

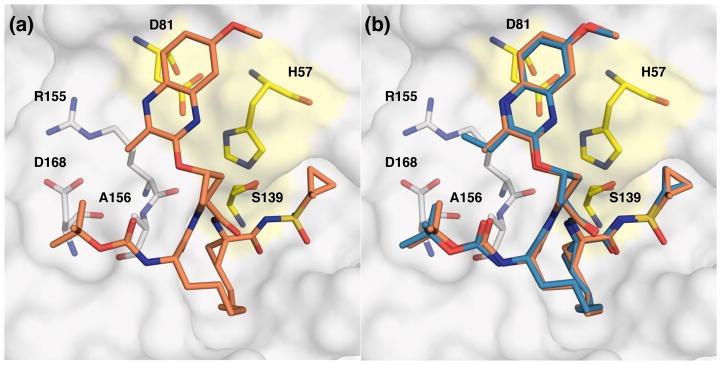

Figure 3.

(a) X-ray crystal structure of WT1a HCV NS3/4A protease in complex with inhibitor 19b and (b) superposition of WT-2 and WT-19a complexes. The protease active site is shown as a surface with inhibitor 19b shown in orange and 2 shown in blue. The catalytic triad is highlighted in yellow and drug resistance residues Arg155, Ala156, and Asp168 are shown as sticks.

Unlike inhibitor 1, the P1–P3 macrocyclic analogues retain potency against the A156T variant. Comparison of the WT-2 and A156T-2 (PDB code: 5EPY) structures shows subtle changes in inhibitor interactions with the mutant protease.38 In the A156T-2 structure the P2 quinoxaline largely maintains interactions with the catalytic residues, but the ethyl group is shifted away from Arg155 side chain toward A156T. Moreover, to accommodate a larger Thr side-chain, the Asp168 side chain adopts another conformation, moving away from Arg155. These changes underlie reduced inhibitor potency against the A156T variant, but unlike 1, inhibitor 2 is able to better accommodate these changes due to a flexible P2 moiety. The 3-methylquinoxaline analogues are more potent against the A156T variant than the corresponding 3-ethylquinoxaline compounds likely due the reduced interactions of the smaller methyl group with the Thr side-chain. Replacing the methyl group with hydrogen at the 3-position of quinoxaline would further reduce interactions with the S2 subsite residues, but could result in a highly flexible P2 moiety, likely destabilizing interactions with the catalytic residues. Thus, a small hydrophobic group at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline is preferred to maintain favorable interactions with Ala156 and avoid steric clashes with the Thr side-chain in the A156T variant.

The improved potency profile of 3-methyquinoxaline compounds led to exploration of bioisosteric replacements of the 3-methyl group with varied size and electronic properties. To that end, analogues 18c and 19c bearing the 3-chloro-7-methoxyquinoxaline at the P2 position were prepared. The protease inhibitory potency profiles of these compounds were excellent and showed improvement against WT, D168A and GT3a over 2. These potency gains were not only maintained in replicon assays but were more significant, with the only exception of A156T variant. Both compounds 18c and 19c were more active than the corresponding 3-methylquinoxaline analogues (18b and 19b) with EC50 values less than 1 nM against WT, R155K and D168V and less than 2 nM against the D168A variant, but experienced about 3- to 6-fold reduction in potency against the A156T variant. However, potency losses against the A156T variant were largely reversed when the P4 tert-butyl group in 18c and 19c was replaced with a larger cyclopentyl moiety to afford 22c and 23c. Similar to the 3-methylquinoxaline compounds, the 3-chloroquinoxaline analogues displayed exceptional potency profiles with EC50 values of less than 5 nM against all drug resistant variants including A156T. These results clearly demonstrate that small hydrophobic groups with weak electron-donating properties at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline can be replaced with weak electron-withdrawing groups without affecting the overall potency profile.

Next, a larger and strongly electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl moiety was explored at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline, leading to inhibitors 18d and 19d. This modification, however, resulted in significant potency losses in both biochemical and replicon assays. Compound 18d was about 2- to 4-fold less active than 2 against WT protease and variants. Analogue 19d with the 1-methylcyclopropylsulfonamide moiety at the P1′ position showed similar trends when compared to the corresponding 19a. In line with biochemical data, both 18d and 19d suffered 2- to 6-fold decrease in replicon potency against WT and drug resistant variants, though 19d maintained relatively good potency profile. In contrast to the results in previous series, the introduction of the larger cyclopentyl P4 capping group, as in 22d and 23d, was detrimental to replicon potency, particularly against the A156T variant. Moreover, compounds in the 3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxaline series were among the least active against the GT3a protease in biochemical assays. These results indicate that strong electron-withdrawing groups at the 3-position of the P2 quinoxaline may be detrimental to potency. However, a recent SAR study indicates that PIs incorporating the 3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxaline can be optimized with modifications at the 7-position of quinoxaline in combination with changes at the P1–P3 macrocycle and P4 capping group.46

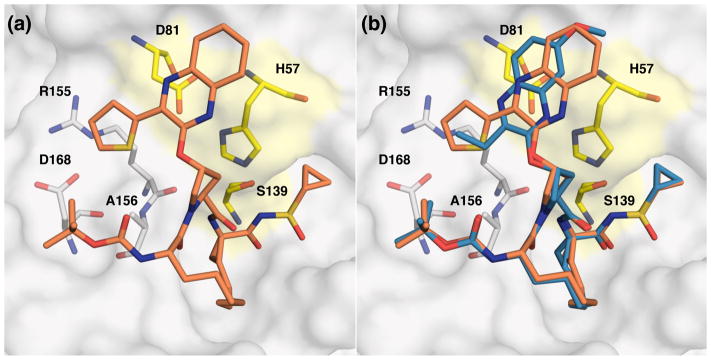

In the absence of a co-crystal structure, the lower inhibitory potencies of compounds in the 3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxaline series against WT protease could not be explained by molecular modeling, which suggested a similar binding conformation of the P2 quinoxaline in 18d as observed for 2 (Figure 4A). Perhaps there are repulsive interactions between trifluoromethyl moiety and the side chain of Asp168, and/or the strong electron-withdrawing effect may weaken the overall interactions of the P2 quinoxaline with the catalytic residues. Potency losses against resistant variants may also result from the larger size of the trifluoromethyl moiety, which is comparable to that of an ethyl group, though both have different topographical shapes.47

Figure 4.

Comparison of lead compound 2 with analogues (a) 18d, and (b) 18e, modeled in the active site of WT HCV NS3/4A protease. Compound 2 is shown in salmon and modified inhibitors are in green. The catalytic triad is highlighted in yellow and drug resistance residues Arg155, Ala156, and Asp168 are in sticks.

To isolate the effects of larger size versus electronic properties on potency, inhibitors 18e and 19e with the larger isopropyl group at the 3-position of the P2 quinoxaline were designed and evaluated. These compounds showed WT protease inhibitory activity similar to the corresponding 3-ethylquinoxaline analogues (2 and 19a), but experienced 2- to 4-fold reduced activity against the D168A variant. A broader reduction in potency was observed for both 18e and 19e in replicon assays against WT and drug resistant variants. The cyclopentyl P4 group in analogues 22e and 23e slightly improved biochemical and replicon potency against WT and D168A variants, but was largely unfavorable to replicon potency against R155K and A156T variants. This trend is broadly similar to the results observed with the 3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxaline series, indicating that both electronic properties and size of the group at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline are important for maintaining potency against drug resistant variants. Modeling indicated that compared to 2 the P2 quinoxaline moiety in 18e has to shift away from the catalytic triad in order to accommodate the larger isopropyl group thereby weakening critical stacking interactions with His57 (Figure 4B). Overall, SAR data from the 3-isopropyl- and 3-(trifluoromethyl)-quinoxaline series supports the hypothesis that large substituents at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline have detrimental effect on inhibitor potency against drug resistant variants.

These findings were further reinforced by the results obtained for the 3-(thiophen-2-yl)quinoxaline analogues 18f and 22f. Based on molecular modeling, the large thiophene moiety in these compounds was expected to make extensive interactions with the residues Arg155 and Ala156, resulting in improved potency against WT protease. However, mutations at these positions as well as at Asp168 would cause significant potency losses, as these residues are crucial for efficient inhibitor binding. As expected, compound 18f (a previously reported NS3/4A PI incorrectly labeled as ABT-450)19,48 showed a 3-fold enhancement in WT biochemical potency but was dramatically less active against the D168A variant, losing over 1800-fold potency. Similarly, in replicon assays analogue 18f showed considerably reduced potency against all drug resistant variants with losses ranging from 20- to 250-fold compared to WT (Table S1 and S2). The cyclopentyl P4 analogue 22f also experienced large potency losses against the variants, albeit to a lesser extent than 18f. Thus inhibitors with large groups at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline are highly susceptible to mutations at residues Arg155, Ala156 and Asp168, leading to poor resistance profiles.

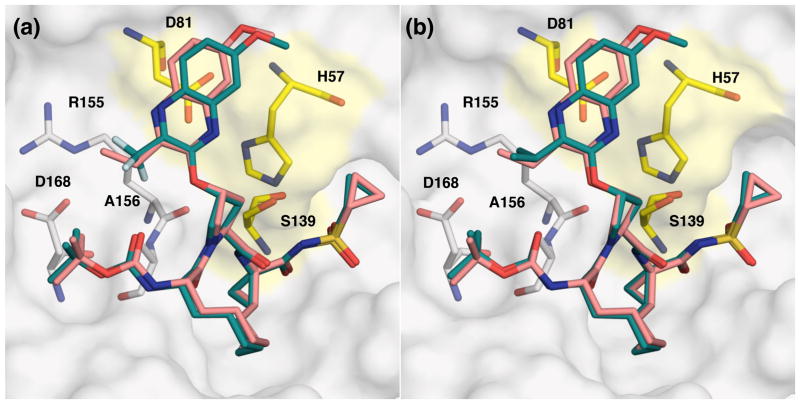

The X-ray crystal structure of inhibitor 18f in complex with WT NS3/4A protease was determined at a resolution of 1.9 Å, providing insights into the binding modes of P2 quinoxaline with a larger thiophene substituent at the 3-position (Figure 5, Table S3, PDB code: 5VP9). Comparison of the WT-18f and WT-2 crystal structures showed significant differences in the interactions of quinoxaline moieties with the catalytic triad and S2 subsite residues. As predicted, the quinoxaline moiety in WT-18f structure is shifted toward the active site to accommodate the larger thiophene substituent. The thiophene ring makes extensive interactions with residues in the S2 subsite, including cation-π interactions with Arg155, likely contributing to the improved potency against the WT protease. As this Arg155 conformation is stabilized by electrostatic interactions with Asp168, mutations at either residue would disrupt inhibitor binding by loss of direct interactions as well as indirect structural effects. In addition, the A156T mutation would result in a steric clash with the thiophene ring, as reflected in the antiviral data for this variant. These biochemical and structural findings are in line with previous studies that show inhibitors that are dependent on extensive interactions with the S2 subsite residues for potency are highly susceptible to mutations at residues Arg155, Ala156 and Asp168.

Figure 5.

(a) X-ray crystal structure of WT1a HCV NS3/4A protease in complex with inhibitor 18f and (b) superposition of WT-2 and WT-18f complexes. The protease active site is shown as a surface with inhibitor 18f shown in orange and 2 shown in blue. The catalytic triad is highlighted in yellow and drug resistance residues Arg155, Ala156, and Asp168 are shown as sticks.

As compounds 18f and 22f lacked the C-7 substituent at the P2 quinoxaline, analogues 18g and 22g were prepared to investigate the effect of this group on inhibitor potency. Compared to 2, analogue 18g experienced about 2-fold decrease in biochemical potency and only minor loss in replicon potency against WT and drug resistant variants. The P4 cyclopentyl analogue 22g resulted in about 2-fold reduced potency compared to the corresponding compound 22a. Thus removal of the C-7 methoxy group has minimal effect on inhibitor potency. The slightly reduced potency of 18g and 22g is likely due to the reduced hydrophobic interactions with the aromatic ring of Tyr56 and the methylene portion of His57 of the catalytic triad. In contrast, the observed potency losses against resistant variants for the 3-(thiophen-2-yl)quinoxaline compounds most likely result from loss of interactions of the 2-thiophene moiety with the S2 subsite residues of the protease.

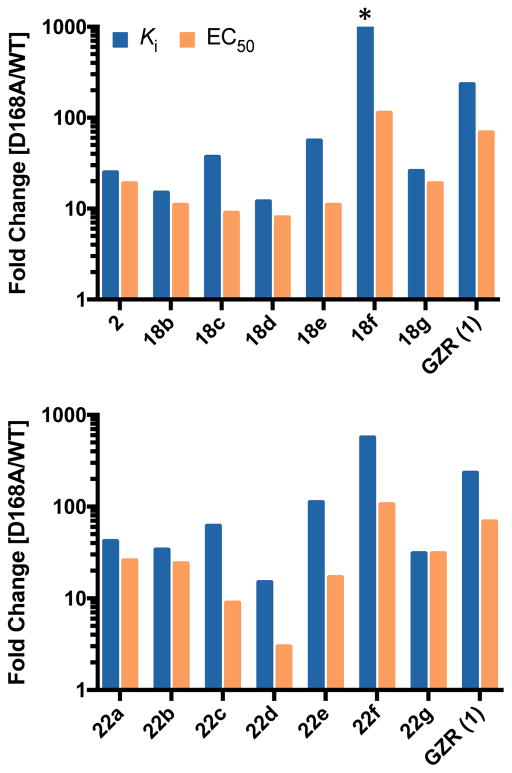

Effects of P2 Substituent Size and Flexibility

Taken together, our SAR results indicate that resistance profiles of compound 2 and analogues are strongly influenced by the substituent at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline and N-terminal capping group. While all PIs showed reduced potency against drug resistance variants in both enzyme inhibition and replicon assays, fold potency losses varied significantly depending on the substituents at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline. To evaluate susceptibility to the clinically important D168A variant, to which all current NS3/4A PIs are susceptible, potencies were normalized to WT for PIs with the same P4 capping groups (Figure 6). Fold changes in Ki against the D168A protease variant for PIs with the same P1′ and P4 capping groups largely trended with the size of the substituent at the 3-position of P2 quinoxaline, with the exception of trifluoromethyl compounds. Losses in potency were significantly higher for compounds with the larger 2-thiophene substituent at the P2 quinoxaline. These results strongly support using the substrate envelope model to reduce direct inhibitor interactions in the S2 subsite, thereby reducing inhibitor susceptibility to drug resistance.

Figure 6.

Resistance profiles of protease inhibitors in enzyme inhibition and antiviral assays for PIs with (a) tert-butyl and (b) cyclopentyl P4 capping groups. Enzyme inhibitory (blue bars) and antiviral (orange bars) activities against the D168A variant were normalized with respect to the wild-type NS3/4A protease domain or wild-type HCV replicon. *Indicates value higher than 1000.

As we and others have shown,31–33,35 the reduced potencies of NS3/4A PIs against drug resistant variants R155K, A156T, and D168A/V mainly result from disruption of the electrostatic interactions between Arg155 and Asp168. Compared to 1, compound 2 and most analogues incorporating flexible P2 quinoxaline showed lower fold-changes in potency against these variants (Table S1 and S2). In these P1–P3 macrocyclic PIs the conformational flexibility of the P2 allows this moiety to adapt to the structural changes caused by mutations at Arg155, Ala156 and Asp168, resulting in better resistance profiles. Potency losses were higher for compound 1 because constraint imposed by the macrocycle does not allow the P2 moiety to adapt to the structural changes resulting from these mutations. Compound 1 and similar P2–P4 macrocyclic PIs, such as voxilaprevir and glecaprevir, are likely to be more susceptible to mutations that cause significant structural changes in the protease active site. However, the P1–P3 macrocyclic compounds reported here, as well as those reported in patent literature that incorporate similar flexible P2 quinoxaline moieties,49 are likely to be more effective against clinically relevant drug resistant variants. More broadly, combining the substrate envelope model with optimal conformational flexibility provides a rational approach to design NS3/4A PIs with improved resistance profiles.

CONCLUSIONS

Drug resistance is a major problem across all DAA classes targeting HCV. As new therapies are developed the potential for drug resistance must be minimized at the outset of inhibitor design. The substrate envelope model provides a rational approach to design robust NS3/4A PIs with improved resistance profiles. Our SAR findings support the hypothesis that reducing PI interactions with residues in the S2 subsite leads to inhibitors with exceptional potency and resistance profiles. Specifically, the P1–P3 macrocyclic inhibitors incorporating flexible P2 quinoxaline moieties bearing small hydrophobic groups at the 3-position maintain excellent potency in both enzymatic and antiviral assays against drug resistant variants. While these inhibitors protrude from the substrate envelope, they leverage interactions with the essential catalytic triad residues and avoid direct contacts with residues that can mutate to confer resistance. Moreover, conformational flexibility at the P2 moiety is essential to efficiently accommodate structural changes due to mutations in the S2 pocket in order to avoid resistance. These insights provide strategies for iterative rounds of inhibitor design with the paradigm that designing inhibitors with flexible P2 quinoxalines, leveraging evolutionarily constrained areas in the protease active site and expanding into the substrate envelope may provide inhibitors that are robust against drug resistant variants.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General

All reactions were performed in oven-dried round bottomed or modified Schlenk flasks fitted with rubber septa under argon atmosphere, unless otherwise noted. All reagents and solvents, including anhydrous solvents, were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. Flash column chromatography was performed using silica gel (230–400 mesh, EMD Millipore). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using silica gel (60 F-254) coated aluminum plates (EMD Millipore), and spots were visualized by exposure to ultraviolet light (UV), exposure to iodine adsorbed on silica gel, and/or exposure to an acidic solution of p-anisaldehyde (anisaldehyde) followed by brief heating. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were acquired on Varian Mercury 400 MHz and Bruker Avance III HD 500 MHz NMR instruments. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm (δ scale) with the residual solvent signal used as reference and coupling constant (J) values are reported in hertz (Hz). Data are presented as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, dd = doublet of doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, br s = broad singlet), coupling constant in Hz, and integration. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Velos Pro mass spectrometer coupled with a Thermo Scientific Accela 1250 UPLC and an autosampler using electrospray ionization (ESI) in the positive mode. The purity of final compounds was determined by analytical HPLC and was found to be ≥95% pure. HPLC was performed on a Waters Alliance 2690 system equipped with a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector and an autosampler under the following conditions: column, Phenomenex Luna-2 RP-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm, 120 Å, Torrance, CA); solvent A, H2O containing 0.1% formic acid (FA), solvent B, CH3CN containing 0.1% FA; gradient, 50% B to 100% B over 15 min followed by 100% B over 5 min; injection volume, 10 μL; flow rate, 1 mL/min. Retention times and purity data for each target compound are provided in the experimental section.

Typical procedures for the synthesis of protease inhibitors using Method A

1-(tert-Butyl) 2-methyl (2S,4R)-4-((3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)pyrrolidine-1,2-dicarboxylate (9a)

A solution of 3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-one 8a (3.0 g, 14.7 mmol) in anhydrous NMP (45 mL) was treated with Cs2CO3 (7.40 g, 22.7 mmol). After stirring the reaction mixture at room temperature for 15 min, proline derivative 3 (6.20 g, 13.3 mmol) was added in one portion. The reaction mixture was heated to 55 °C, stirred for 4 h, and then another portion of proline derivative 3 (0.48 g, 1.0 mmol) was added. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at 55 °C for an additional 2 h, cooled to room temperature, quenched with aqueous 1 N HCl solution (150 mL), and extracted with EtOAc (300 mL). The organic fraction was washed successively with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and NaCl (150 mL each), dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography using 15–30% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to provide 9a (5.50 g, 87%) as a white foamy solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) (mixture of rotamers, major rotamer) δ 7.85 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.18 (m, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.73 (br s, 1 H), 4.47 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.98–3.86 (m, 5 H), 3.78 (s, 3 H), 2.92 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.68–2.60 (m, 1 H), 2.43–2.36 (m, 1 H), 1.43 (s, 9 H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.56, 160.59, 155.38, 154.02, 148.95, 141.26, 134.12, 129.07, 119.02, 106.11, 80.76, 73.81, 58.43, 55.93, 52.73, 52.40, 36.88, 28.47, 26.68, 11.97 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C22H30N3O6, 432.2129; found 432.2135.

1-(tert-Butyl) 2-methyl (2S,4R)-4-((7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)pyrrolidine-1,2-dicarboxylate (9d)

The same procedure was used as described above for compound 9a. 7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2(1H)-one 8d (4.76 g, 19.5 mmol) in NMP (65 mL) was treated with Cs2CO3 (9.80 g, 30.0 mmol) and proline derivative 3 (9.0 g, 19.3 mmol) to provide 9d (6.50 g, 71%) as a pale yellow foamy solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) (mixture of rotamers, major rotamer) δ 7.77 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.48–7.43 (m, 2 H), 5.76 (br s, 1 H), 4.50 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.97–3.91 (m, 5 H), 3.78 (s, 3 H), 2.69–2.64 (m, 1 H), 2.41–2.34 (m, 1 H), 1.42 (s, 9 H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.43, 159.58, 153.98, 152.11, 138.39, 137.22, 127.99, 125.73, 120.70 (q, J = 273.4 Hz), 107.64, 80.69, 74.62, 58.27, 56.02, 52.32, 52.11, 36.70, 28.34 ppm; 19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3); −67.73 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C21H25F3N3O6, 472.1690; found 472.1689.

Methyl (2S,4R)-1-((S)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)non-8-enoyl)-4-((3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)pyrrolidine-2-carboxylate (12a)

A solution of ester 9a (4.80 g, 11.1 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (30 mL) was treated with a solution of 4 N HCl in 1,4-dioxane (30 mL). After stirring the reaction mixture at room temperature for 3 h, solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried under high vacuum. The pale yellow solid was triturated with diethyl ether (3 × 30 mL) and dried under high vacuum to yield the amine salt 10a (4.0 g, 98%) as an off-white powder.

A mixture of amine salt 10a (4.0 g, 10.9 mmol) and (S)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)non-8-enoic acid 11 (3.0 g, 11.1 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (60 mL) was treated with DIEA (7.30 mL, 44.2 mmol) and HATU (6.35 g, 16.7 mmol). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h, then diluted with EtOAc (400 mL), and washed successively with aqueous 0.5 N HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and saturated aqueous NaCl (250 mL each). The organic portion was dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography using 20–30% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to provide 12a (5.50 g, 86%) as a white foamy solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) (mixture of rotamers, major rotamer) δ 7.86 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.20 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.12 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.87–5.75 (m, 2 H), 5.20 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 5.02–4.92 (m, 2 H), 4.73 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.38 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.17 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.06 (dd, J = 11.6, 4.4 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 3.78 (s, 3 H), 2.90 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.69–2.64 (m, 1 H), 2.41–2.34 (m, 1 H), 2.05 (app q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2 H), 1.82–1.74 (m, 1 H), 1.63–1.56 (m, 1 H), 1.45–1.25 (m, 18 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.34, 171.96, 160.61, 155.61, 155.13, 148.95, 141.08, 139.18, 129.22, 119.08, 114.58, 106.14, 79.84, 74.48, 58.19, 55.91, 52.88, 52.67, 52.05, 35.16, 33.88, 32.88, 29.14, 28.96, 28.46, 26.52, 24.92, 11.86 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C31H45N4O7 585.3283; found 585.3286.

Methyl (2S,4R)-1-((S)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)non-8-enoyl)-4-((7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)pyrrolidine-2-carboxylate (12d)

The same procedure was used as described above for compound 12a. Compound 9d (6.0 g, 12.7 mmol) was treated with 4 N HCl (40 mL) to afford amine salt 10d (5.10 g, 12.5 mmol), which was coupled with acid 11 (3.80 g, 14.0 mmol) using DIEA (9.25 mL, 56.0 mmol) and HATU (7.60 g, 20.0 mmol) to provide 12d (6.40 g, 81%) as a pale yellow foamy solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) (mixture of rotamers, major rotamer) δ 7.78 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.48 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.44 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1 H), 5.86 (br s, 1 H), 5.84–5.78 (m, 1 H), 5.18 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.01–4.92 (m, 2 H), 4.75 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.35 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 4.19 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.08 (dd, J = 11.5, 4.5 Hz, 1 H), 3.95 (s, 3 H), 3.78 (s, 3 H), 2.70–2.65 (m, 1 H), 2.41–2.35 (m, 1 H), 2.04 (app q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.80–1.75 (m, 1 H), 1.60–1.54 (m, 1 H), 1.45–1.28 (m, 15 H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.10, 171.60, 159.99, 155.37, 151.78, 138.98, 138.41, 136.93, 134.40 (q, J = 36.3 Hz), 127.85, 125.66, 120.53 (q, J = 273.4 Hz), 114.33, 107.54, 79.58, 75.05, 57.83, 55.91, 52.44, 52.33, 51.75, 34.77, 33.65, 32.70, 28.91, 28.73, 28.18, 24.70 ppm; 19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3); −67.73 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C30H40F3N4O7, 625.2844; found 625.2844.

tert-Butyl ((S)-1-((2S,4R)-2-(((1R,2S)-1-((cyclopropylsulfonyl)carbamoyl)-2-vinylcyclopropyl)carbamoyl)-4-((3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)pyrrolidin-1-yl)-1-oxonon-8-en-2-yl)carbamate (16a)

A solution of ester 12a (5.86 g, 10.0 mmol) in THF-H2O mixture (1:1, 140 mL) was treated with LiOH.H2O (1.40 g, 33.4 mmol). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to ~5 °C, acidified to a pH of 2.0 by slow addition of aqueous 0.25 N HCl (~ 200 mL), and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 400 mL). The organic portions were washed separately with saturated aqueous NaCl (200 ml), dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The gummy residue was dissolved in CHCl3 (50 mL), concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried under high vacuum overnight to yield the acid 13a (5.70 g, 100%) as a white foamy solid.

A mixture of acid 13a (2.10 g, 3.7 mmol) and amine salt 1442 (1.20 g, 4.5 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (35 mL) was treated with DIEA (2.43 mL, 14.7 mmol) and HATU (2.1 g, 5.5 mmol). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2.5 h, then diluted with EtOAc (300 mL) and washed successively with aqueous 0.5 N HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and saturated aqueous NaCl (200 mL each). The organic portion was dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography using 50– 70% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to provide the bis-olefin compound 16a (2.50 g, 86%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.24 (s, 1 H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.18 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.13 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.04 (s, 1 H), 5.91 (br s, 1 H), 5.85–5.73 (m, 2 H), 5.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 5.27 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.14 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.01–4.90 (m, 2 H), 4.47 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.38–4.33 (m, 1 H), 4.20 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.02 (dd, J = 11.2, 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.96–2.84 (m, 3 H), 2.56–2.51 (m, 2 H), 2.11 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.05–1.99 (m, 3 H), 1.74–1.54 (m, 2 H), 1.47–1.10 (m, 21 H), 1.08–1.03 (m, 2 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.09, 172.58, 168.69, 160.54, 155.89, 154.99, 148.88, 140.95, 139.07, 134.69, 132.71, 129.45, 119.02, 118.77, 114.67, 106.13, 80.0, 74.66, 60.61, 55.91, 53.42, 52.62, 41.83, 35.46, 34.47, 33.89, 32.40, 31.39, 28.98, 28.89, 28.47, 26.68, 25.47, 23.83, 11.85, 6.68, 6.26 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C39H55N6O9S, 783.3746; found 783.3734.

tert-Butyl ((S)-1-((2S,4R)-4-((3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-2-(((1R,2S)-1-(((1-methylcyclopropyl)sulfonyl)carbamoyl)-2-vinylcyclopropyl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)-1-oxonon-8-en-2-yl)carbamate (17a)

The same procedure was used as described above for compound 16a. Acid 13a (1.50 g, 2.6 mmol) was coupled with amine salt 1543 (0.90 g, 3.2 mmol) using DIEA (1.75 mL, 10.6 mmol) and HATU (1.50 g, 3.9 mmol) to provide the bisolefin compound 17a (1.75 g, 84%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.02 (s, 1 H), 7.84 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.13 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.06 (s, 1 H), 5.90 (br s, 1 H), 5.83–5.73 (m, 2 H), 5.37 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.27 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.14 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.98 (dd, J = 17.2, 1.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.92 (dd, J = 10.4, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.48 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.39–4.33 (m, 1 H), 4.16 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.02 (dd, J = 11.6, 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.89 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.57–2.50 (m, 2 H), 2.12 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.05– 1.99 (m, 3 H), 1.75–1.58 (m, 4 H), 1.49 (s, 3 H), 1.45–1.18 (m, 19 H), 0.93–0.79 (m, 2 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.79, 172.41, 167.51, 160.31, 155.71, 154.76, 148.63, 140.73, 138.85, 134.41, 132.60, 129.18, 118.80, 118.54, 114.41, 105.89, 79.74, 74.42, 60.36, 55.68, 53.17, 52.43, 41.71, 36.56, 35.23, 34.22, 33.64, 32.19, 28.70, 28.67, 28.25, 26.43, 25.35, 23.49, 18.37, 14.27, 13.29, 11.64 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C40H57N6O9S, 797.3902; found 797.3887.

tert-Butyl ((2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-14a-((cyclopropylsulfonyl)carbamoyl)-2-((3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,14a,15,16,16a-hexadecahydrocyclopropa[ e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecin-6-yl)carbamate (2)

A degassed solution of bis-olefin 16a (1.40 g, 1.8 mmol) in 1,2-DCE (300 mL) was heated to 50 °C under argon, then Zhan 1b catalyst (0.150 g, 0.20 mmol) was added in two portions over 10 min. The resulting reaction mixture was heated to 70 °C and stirred for 6 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography using 50–80% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to yield the P1–P3 macrocyclic product 2 (0.72 g, 53%) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.28 (s, 1 H), 7.84 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.20–7.15 (m, 2 H), 6.91 (s, 1 H), 5.90 (br s, 1 H), 5.69 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.14 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.96 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.59 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.49 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.30–4.24 (m, 1 H), 4.02 (dd, J = 10.8, 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.94– 2.85 (m, 3 H), 2.70–2.51 (m, 3 H), 2.31 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 1.93–1.64 (m, 2 H), 1.60–1.05 (m, 24 H), 0.95–0.89 (m, 1 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.15, 173.28, 168.02, 160.29, 155.00, 154.90, 148.66, 140.88, 136.31, 134.28, 128.90, 124.47, 118.82, 105.91, 79.84, 74.68, 59.45, 55.72, 53.08, 51.92, 44.57, 34.65, 32.81, 31.01, 29.70, 28.14, 27.11, 27.16, 26.31, 26.06, 22.16, 20.92, 11.56, 6.67, 6.12 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C37H51N6O9S, 755.3433; found 755.3410. Anal. HPLC: tR 14.23 min, purity 97%.

tert-Butyl ((2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-2-((3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-14a-(((1-methylcyclopropyl)sulfonyl)carbamoyl)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,14a,15,16,16a-hexadecahydrocyclopropa[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecin-6-yl)carbamate (19a)

The same procedure was used as described above for compound 2. Bis-olefin 17a (1.45 g, 1.8 mmol) was treated with Zhan 1b catalyst (0.150 g, 0.20 mmol) in 1,2-DCE (300 mL) to afford the P1–P3 macrocyclic product 19a (1.0 g, 71%) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.16 (s, 1 H), 7.82 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.18–7.15 (m, 2 H), 6.94 (s, 1 H), 5.90 (br s, 1 H), 5.69 (q, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.99 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.59 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.49 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.30–4.25 (m, 1 H), 4.04 (dd, J = 11.6, 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.87 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.70–2.51 (m, 3 H), 2.33 (q, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 1.92–1.68 (m, 4 H), 1.60–1.15 (m, 24 H), 0.85–0.78 (m, 2 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.19, 173.24, 167.0, 160.23, 154.99, 154.88, 148.73, 140.84, 136.26, 134.25, 129.03, 124.89, 118.72, 105.92, 79.84, 74.67, 59.48, 55.72, 53.11, 51.92, 44.71, 36.43, 34.68, 32.80, 29.62, 28.14, 27.09, 26.38, 26.12, 22.19, 20.93, 18.17, 14.51, 12.50, 11.54 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C38H53N6O9S, 769.3589; found 769.3561. Anal. HPLC: tR 15.01 min, purity 99%.

Cyclopentyl ((2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-14a-((cyclopropylsulfonyl)carbamoyl)-2-((3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,14a,15,16,16a-hexadecahydrocyclopropa[ e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecin-6-yl)carbamate (22a)

Compound 2 (0.40 g, 0.53 mmol) was treated with a solution of 4 N HCl in 1,4-dioxane (10 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h, then concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried under high vacuum. The off-white solid was triturated with diethyl ether (3 × 10 mL) and dried under high vacuum to yield the amine salt 20a (0.37 g, 100%) as a white powder.

A solution of the above amine salt 20a (0.37 g, 0.53 mmol) in anhydrous CH3CN (15 mL) was treated with DIEA (0.35 mL, 2.1 mmol) and N-(cyclopentyloxycarbonyloxy)-succinimide (0.15 g, 0.66 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 36 h, then concentrated under reduced pressure and dried under high vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography using 50–90% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to provide the target compound 22a (0.32 g, 79%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.29 (s, 1 H), 7.83 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 2 H), 6.94 (s, 1 H), 5.93 (br s, 1 H), 5.70 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.26 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.96 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.86–4.82 (m, 1 H), 4.60 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.45 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.34–4.28 (m, 1 H), 4.03 (dd, J = 11.2, 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.93–2.85 (m, 3 H), 2.70–2.48 (m, 3 H), 2.30 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 1.93–1.23 (m, 23 H), 1.15–1.06 (m, 2 H), 0.96–0.88 (m, 1 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.18, 173.03, 168.04, 160.28, 155.65, 154.93, 148.78, 140.90, 136.27, 134.20, 128.92, 124.46, 118.80, 105.92, 77.87, 74.55, 59.47, 55.72, 53.01, 52.17, 44.54, 34.58, 32.72, 32.63, 32.59, 31.01, 29.70, 27.14, 27.05, 26.40, 26.05, 23.56, 22.16, 20.90, 11.61, 6.67, 6.12 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C38H51N6O9S, 767.3433; found 767.3408. Anal. HPLC: tR 14.50 min, purity 98%.

Cyclopentyl ((2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-2-((3-ethyl-7-methoxyquinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-14a-(((1-methylcyclopropyl)sulfonyl)carbamoyl)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,14a,15,16,16a-hexadecahydrocyclopropa[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecin-6-yl)carbamate (23a)

The same procedure was used as described above for compound 22a. Compound 19a (0.40 g, 0.52 mmol) was treated with 4 N HCl in 1,4-dioxane (10 mL) to yield the amine salt 21a, which was treated with DIEA (0.35 mL, 2.1 mmol) and N-(cyclopentyloxycarbonyloxy)-succinimide (0.15 g, 0.66 mmol) to provide the target compound 23a (0.30 g, 74%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.17 (s, 1 H), 7.81 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 2 H), 6.93 (s, 1 H), 5.92 (br s, 1 H), 5.70 (q, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.26 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.99 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.86–4.81 (m, 1 H), 4.59 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.45 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.34–4.28 (m, 1 H), 4.04 (dd, J = 11.6, 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.87 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.70–2.48 (m, 3 H), 2.32 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 1.92–1.23 (m, 27 H), 0.85–0.78 (m, 2 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.21, 172.99, 166.98, 160.22, 155.63, 154.90, 148.84, 140.85, 136.22, 134.36, 129.05, 124.88, 118.70, 105.93, 77.86, 74.54, 59.51, 55.71, 53.05, 52.16, 44.70, 36.43, 34.61, 32.72, 32.64, 32.58, 29.63, 27.13, 27.06, 26.47, 26.12, 23.56, 22.18, 20.94, 18.17, 14.49, 12.50, 11.59 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C39H53N6O9S, 781.3589; found 781.3561. Anal. HPLC: tR 15.25 min, purity 99%.

Typical procedures for the synthesis of protease inhibitors using Method B

Ethyl (1R,2S)-1-((2S,4R)-1-((S)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)non-8-enoyl)-4-((7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamido)-2-vinylcyclopropane-1-carboxylate (25d)

A solution of ester 12d (6.40 g, 10.25 mmol) in THF-H2O (1:1 mixture, 140 mL) was treated with LiOH.H2O (1.38 g, 32.0 mmol). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, then cooled to ~5 °C, acidified to a pH of 2.0 by slow addition of aqueous 0.25 N HCl (~ 200 mL), and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 500 mL). The organic portions were washed separately with saturated aqueous NaCl (250 ml), dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The gummy residue was dissolved in CHCl3 (50 mL), concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried under high vacuum to yield the acid 13d (6.12 g, 98%) as a pale yellow foamy solid.

A solution of acid 13d (6.12 g, 10.0 mmol) and amine salt 24 (2.50 g, 13.0 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (100 mL) was treated with DIEA (9.10 mL, 55.0 mmol), HATU (5.30 g, 14.0 mmol) and DMAP (0.60 g, 4.9 mmol). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 14 h, then diluted with EtOAc (500 mL), and washed successively with aqueous 1.0 N HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and saturated aqueous NaCl (250 mL each). The organic portion was dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography using 25–35% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to provide the bisolefin compound 25d (6.54 g, 87%) as a pale yellow foamy solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) (mixture of rotamers, major rotamer) δ 7.78 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.53 (br s, 1 H), 7.47 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.43 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 5.88 (br s, 1 H), 5.81–5.70 (m, 2 H), 5.30 (dd, J = 16.8, 0.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.14–5.10 (m, 2 H), 5.01–4.89 (m, 2 H), 4.79 (dd, J = 14.0, 5.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.35–4.29 (m, 1 H), 4.21–4.08 (m, 3 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.90–2.82 (m, 1 H), 2.48–2.38 (m, 1 H), 2.16 (q, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 2.04–1.98 (m, 2 H), 1.86 (dd, J = 8.0, 5.2 Hz, 1 H), 1.66–1.52 (m, 2 H), 1.46 (dd, J = 9.6, 5.6 Hz, 1 H), 1.43–1.21 (m, 19 H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.02, 171.00, 169.87, 159.62, 155.52, 152.03, 138.92, 138.48, 137.16, 133.66, 128.02, 125.73, 120.72 (q, J = 273.6 Hz), 118.08, 114.52, 107.66, 79.98, 75.26, 61.40, 58.41, 56.02, 52.58, 52.43, 40.14, 33.89, 33.77, 32.76, 32.62, 28.97, 28.78, 28.31, 25.18, 23.11, 14.48 ppm; 19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3); −67.77 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C37H49F3N5O8, 748.3528; found 748.3514.

Ethyl (2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-6-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-2-((7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,15,16,16atetradecahydrocyclopropa[ e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecine-14a(5H)-carboxylate (26d)

A degassed solution of bis-olefin 25d (1.50 g, 2.0 mmol) in 1,2-DCE (300 mL) was heated to 50 °C under argon, then Zhan 1b catalyst (0.150 g, 0.20 mmol) was added in two portions over 10 min. The resulting mixture was heated to 70 °C and stirred for 5 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography using 25–35% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to yield the P1–P3 macrocyclic product 26d (1.0 g, 70%) as an off-white foamy solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.77 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.47 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.44 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.03 (br s, 1 H), 5.84–5.80 (m, 1 H), 5.56–5.49 (m, 1 H), 5.32–5.22 (m, 2 H), 4.92 (q, J = 4.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.49 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.24–4.05 (m, 4 H), 3.95 (s, 3 H), 3.05–2.99 (m, 1 H), 2.41–2.35 (m, 1 H), 2.24–2.14 (m, 3 H), 1.93–1.86 (m, 2 H), 1.66–1.60 (m, 1 H), 1.55 (dd, J = 96, 5.2 Hz, 1 H), 1.46–1.20 (m, 18 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.81, 171.95, 169.74, 159.69, 155.21, 152.20, 138.56, 137.25, 134.50, 128.08, 125.91, 125.84, 120.80 (q, J = 276 Hz), 107.73, 80.04, 75.42, 61.50, 58.08, 56.13, 52.21, 51.39, 41.36, 32.16, 31.77, 28.45, 28.10, 28.02, 26.37, 25.74, 23.70, 22.57, 14.72 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C35H45F3N5O8, 720.3215; found 720.3203.

tert-Butyl ((2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-14a-((cyclopropylsulfonyl)carbamoyl)-2-((7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,14a,15,16,16a-hexadecahydrocyclopropa[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecin-6-yl)carbamate (18d)

A solution of ester 26d (1.0 g, 1.4 mmol) in THF-MeOH-H2O (1:1:1 mixture, 20 mL) was treated with LiOH.H2O (0.18 g, 4.2 mmol). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, then cooled to ~5 °C, acidified to a pH of 2.0 by slow addition of aqueous 0.25 N HCl, and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 150 mL). The organic portions were washed separately with saturated aqueous NaCl (100 ml), dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The gummy residue was dissolved in CHCl3 (10 mL), concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried under high vacuum to yield the acid 27d (0.95 g, 98%) as a pale yellow foamy solid.

A mixture of acid 27d (0.40 g, 0.58 mmol) and CDI (0.131 g, 0.81 mmol) in anhydrous THF (8 mL) was heated at reflux for 1.5 h. The solution was cooled to room temperature and slowly added to a solution of cyclopropanesulfonamide 28 (0.10 g, 0.82 mmol) in anhydrous THF (4 mL) followed by DBU (0.12 mL, 0.81 mmol). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, then quenched with aqueous 0.5 N HCl to pH ~2. Solvents were partially evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (2 × 100 mL). The combined organic portions were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl (100 mL), dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography using 40–70% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to afford the title compound 18d (0.28 g, 60%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.28 (s, 1 H), 7.83 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.49 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.42 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.87 (s, 1 H), 5.92 (br s, 1 H), 5.70 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.13 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.97 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.62–4.56 (m, 2 H), 4.23–4.17 (m, 1 H), 4.01 (dd, J = 11.6, 3.2 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.93–2.87 (m, 1 H), 2.68–2.50 (m, 3 H), 2.31 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 1.95–1.54 (m, 2 H), 1.53–1.02 (m, 21 H), 0.96–0.88 (m, 1 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 176.99, 173.31, 167.91, 159.45, 154.93, 151.76, 138.27, 136.99, 136.32, 134.56 (q, J = 36.2 Hz), 127.99, 125.57, 124.53, 120.8 (q, J = 274.0 Hz), 107.40, 79.76, 75.54, 59.44, 55.89, 52.72, 51.86, 44.65, 34.61, 32.82, 31.02, 29.61, 28.02, 27.04, 25.99, 22.21, 20.93, 6.67, 6.12 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C36H46F3N6O9S, 795.2994; found 795.2974. Anal. HPLC: tR 14.59 min, purity 100%.

tert-Butyl ((2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-2-((7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-14a-(((1-methylcyclopropyl)sulfonyl)carbamoyl)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,14a,15,16,16a-hexadecahydrocyclopropa[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecin-6-yl)carbamate (19d)

The same procedure was used as described above for compound 18d. Acid 27d (0.43 g, 0.62 mmol) was treated with CDI (0.141 g, 0.87 mmol), 1-methylcyclopropanesulfonamide 29 (0.118 g, 0.87 mmol) and DBU (0.13 mL, 0.87 mmol) to afford the title compound 19d (0.34 g, 68%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.15 (s, 1 H), 7.83 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.48 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.42 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.90 (s, 1 H), 5.91 (s, 1 H), 5.70 (q, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.14 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 5.00 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.62–4.55 (m, 2 H), 4.24–4.18 (m, 1 H), 4.02 (dd, J = 11.6, 3.6 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.71–2.51 (m, 3 H), 2.33 (q, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 1.93–1.75 (m, 4 H), 1.56–1.18 (m, 21 H), 0.85–0.78 (m, 2 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.30, 173.46, 167.15, 159.68, 155.16, 152.01, 138.50, 137.23, 136.50, 134.60 (q, J = 36.0 Hz), 128.23, 125.79, 125.19, 120.83 (d, J = 274.0 Hz), 107.65, 80.01, 75.79, 59.70, 56.12, 52.97, 52.08, 45.03, 36.65, 34.86, 33.06, 29.81, 28.26, 27.31, 27.24, 26.32, 22.47, 21.21, 18.42, 14.73, 12.77 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C37H48F3N6O9S, 809.3150; found 809.3129. Anal. HPLC: tR 15.23 min, purity 99%.

Cyclopentyl ((2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-14a-((cyclopropylsulfonyl)carbamoyl)-2-((7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,14a,15,16,16a-hexadecahydrocyclopropa[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecin-6-yl)carbamate (22d)

Compound 18d (0.40 g, 0.52 mmol) was treated with a solution of 4 N HCl in 1,4-dioxane (10 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h, concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried under high vacuum. The pale yellow solid was triturated with diethyl ether (3 × 10 mL) and dried under high vacuum to yield the amine salt 20d (0.37 g, 100%) as a white powder.

A solution of the above amine salt 20d (0.37 g, 0.52 mmol) in anhydrous CH3CN (15 mL) was treated with DIEA (0.35 mL, 2.1 mmol) and N-(cyclopentyloxycarbonyloxy)-succinimide (0.15 g, 0.66 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, then concentrated under reduced pressure and dried under high vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography using 50–90% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent to provide the target compound 22d (0.30 g, 74%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.27 (s, 1 H), 7.82 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.48 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.42 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.78 (s, 1 H), 5.95 (s, 1 H), 5.70 (q, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 5.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.98 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.74–4.69 (m, 1 H), 4.60 (t, J = 7.6, 1 H), 4.54 (d, J = 11.6, 1 H), 4.25–4.19 (m, 1 H), 3.99 (dd, J = 11.6, 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.94–2.88 (m, 1 H), 2.68–2.50 (m, 3 H), 2.31 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 1.94–1.24 (m, 21 H), 1.20–1.07 (m, 2 H), 0.96–0.89 (m, 1 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.33, 173.29, 168.27, 159.68, 155.87, 152.08, 138.56, 137.24, 136.47, 134.74 (q, J = 36.0 Hz), 128.24, 125.75, 124.79, 120.87 (d, J = 273.2 Hz), 107.62, 78.02, 75.70, 59.68, 56.11, 52.90, 52.35, 44.83, 34.71, 32.92, 32.81, 32.64, 31.26, 29.87, 27.27, 26.24, 23.81, 23.75, 22.49, 21.11, 6.89, 6.34 ppm; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C37H46F3N6O9S, 807.2994; found 807.2976. Anal. HPLC: tR 14.98 min, purity 99%.

Cyclopentyl ((2R,6S,13aS,14aR,16aS,Z)-2-((7-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)oxy)-14a-(((1-methylcyclopropyl)sulfonyl)carbamoyl)-5,16-dioxo-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13a,14,14a,15,16,16a-hexadecahydrocyclopropa[e]pyrrolo[1,2-a][1,4]diazacyclopentadecin-6-yl)carbamate (23d)

The same procedure was used as described above for compound 22d. Compound 19d (0.40 g, 0.52 mmol) was treated with 4 N HCl in 1,4-dioxane (10 mL) to yield the amine salt 21d, which was treated with DIEA (0.35 mL, 2.1 mmol) and N-(cyclopentyloxycarbonyloxy)-succinimide (0.15 g, 0.66 mmol) to provide the target compound 23d (0.30 g, 74%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.18 (s, 1 H), 7.83 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.48 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.41 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.94 (s, 1 H), 5.94 (s, 1 H), 5.70 (q, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.28 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 5.00 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.74– 4.69 (m, 1 H), 4.60 (t, J = 7.6, 1 H), 4.54 (d, J = 12.0, 1 H), 4.25–4.19 (m, 1 H), 4.00 (dd, J = 11.6, 3.6 Hz, 1 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.68–2.50 (m, 3 H), 2.31 (q, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 1.92–1.20 (m, 24 H), 0.85–0.78 (m, 2 H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.33, 173.25, 167.13, 159.68, 155.84, 152.08, 138.56, 137.24, 136.44, 134.75 (q, J = 35.2 Hz), 128.25, 125.74, 125.21, 120.86 (d, J = 274.0 Hz), 107.62, 78.02, 75.71, 59.73, 56.12, 52.89, 52.34, 45.03, 36.65, 34.73, 32.93, 32.82, 32.64, 29.83, 27.26, 27.21, 26.29, 23.81, 23.75, 22.52, 21.23, 18.42, 14.73, 12.76 ppm. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C38H48F3N6O9S, 821.3150; found 821.3133. Anal. HPLC: tR 15.65 min, purity 97%.

Enzyme Inhibition Assays

For each assay, 2 nM of NS3/4A protease (GT1a, D168A and GT3a) was pre-incubated at room temperature for 1 h with increasing concentration of inhibitors in assay buffer [50 mM Tris, 5% glycerol, 10 mM DTT, 0.6 mM LDAO, and 4% dimethyl sulfoxide]. Inhibition assays were performed in nonbinding surface 96-well black half-area plates (Corning) in a reaction volume of 60 μL. The proteolytic reaction was initiated by the injection of 5 μL of HCV NS3/4A protease substrate (AnaSpec), to a final concentration of 200 nM and kinetically monitored using a Perkin Elmer EnVision plate reader (excitation at 485 nm, emission at 530 nm). Three independent data sets were collected for each inhibitor with each protease construct. Each inhibitor titration included at least 12 inhibitor concentration points, which were globally fit to the Morrison equation to obtain the Ki value.

Cell-Based Drug Susceptibility Assays

Mutations (R155K, A516T, D168A and D168V) were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using a Con1 (genotype 1b) luciferase reporter replicon containing the H77 (genotype 1a) NS3 sequence.50 Replicon RNA of each protease variant was introduced into Huh7 cells by electroporation. Replication was then assessed in the presence of increasing concentrations of protease inhibitors by measuring luciferase activity (relative light units) 96 h after electroporation. The drug concentrations required to inhibit replicon replication by 50% (EC50) were calculated directly from the drug inhibition curves.

Crystallization and structure determination

Protein expression and purification were carried out as previously described (see Supporting Information for details).32 The Ni-NTA purified WT1a protein was thawed, concentrated to 3 mg/mL, and loaded on a HiLoad Superdex75 16/60 column equilibrated with gel filtration buffer (25 mM MES, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 2 mM DTT, pH 6.5). The protease fractions were pooled and concentrated to 25 mg/mL with an Amicon Ultra-15 10 kDa filter unit (Millipore). The concentrated samples were incubated for 1 h with 3:1 molar excess of inhibitor. Diffraction-quality crystals were obtained overnight by mixing equal volumes of concentrated protein solution with precipitant solution (20–26% PEG-3350, 0.1 M sodium MES buffer, 4% ammonium sulfate, pH 6.5) at RT or 15 °C in 24-well VDX hanging drop trays. Crystals were harvested and data was collected at 100 K. Cryogenic conditions contained the precipitant solution supplemented with 15% glycerol or ethylene glycol.

Diffraction data were collected using an in-house Rigaku X-ray system with a Saturn 944 detector. All datasets were processed using HKL-3000.51 Structures were solved by molecular replacement using PHASER.52 The WT-2 complex structure (PDB code: 5EPN)38 was used as the starting structure for all structure solutions. Model building and refinement were performed using Coot53 and PHENIX,54 respectively. The final structures were evaluated with MolProbity55 prior to deposition in the PDB. To limit the possibility of model bias throughout the refinement process, 5% of the data were reserved for the free R-value calculation.56 Structure analysis, superposition and figure generation were done using PyMOL.57 X-ray data collection and crystallographic refinement statistics are presented in the Supporting Information (Table S3).

Molecular Modeling

Molecular modeling was carried out using MacroModel (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY).58 Briefly, inhibitors were modeled into the active site of WT1a and A156T proteases using the WT-2 and A156T-2 co-complex structures (PDB code: 5EPN and 5EPY).38 Structures were prepared using the Protein Preparation tool in Maestro 11. 2D chemical structures were modified with the appropriate changes using the Build tool in Maestro. Once modeled, molecular energy minimizations were performed for each inhibitor–protease complex using the PRCG method with 2500 maximum iterations and 0.05 gradient convergence threshold. PDB files of modeled complexes were generated in Maestro for structural analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the NIH (R01 AI085051). ANM was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH (F31 GM119345). MJ was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC). We thank Dr. Kiran K. Reddy and members of the Schiffer and Miller laboratories for helpful discussions.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CDI

1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole

- DBU

1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene

- 1,2-DCE

1,2-dichloroethane

- DIEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- GT

genotype

- HATU

1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo-[4,5-b]-pyridinium 3-oxid hexafl uorophosphate

- NMP

N-methylpyrrolidinone

- PI

protease inhibitor

- RT

room temperature

- SAR

structure− activity relationship

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest. AN, CJP and WH are employees of Monogram Biosciences.

Accessions Codes

The PDB accession codes for inhibitors 18f- and 19b-bound WT NS3/4A protease X-ray structures are 5VP9 and 5VOJ. Authors will release the atomic coordinates and experimental data upon article publication.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Synthesis of intermediates and final compounds

Protein expression, purification and Km experiments

Molecular formula strings

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) [Accessed February 6: 2016];Hepatitis C, Fact Sheet. (Updated July 2016): http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/

- 2.Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:553–562. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]