Significance

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) belongs to the alphavirus family, the members of which have enveloped icosahedral capsids. The maturation process of alphaviruses involves proteolysis of some of the structural proteins before assembling with nucleocapsids to produce mature virions. We mutated the proteolytic cleavage site on E2 envelope protein, which is necessary in initiating the maturation process. Noninfectious virus-like particles (VLP) equivalent to “immature” fusion incompetent particles were produced to study the immature conformation of CHIKV. We describe the 6.8-Å resolution electron microscopy structure of “immature” CHIK VLPs. Structural differences between the mature and immature VLPs show that posttranslational processing of the envelope proteins and nucleocapsid is necessary to allow exposure of the fusion loop on glycoprotein E1 to produce an infectious virus.

Keywords: alphavirus, Chikungunya virus, maturation, cryo-electron microscopy, conformational changes

Abstract

Cleavage of the alphavirus precursor glycoprotein p62 into the E2 and E3 glycoproteins before assembly with the nucleocapsid is the key to producing fusion-competent mature spikes on alphaviruses. Here we present a cryo-EM, 6.8-Å resolution structure of an “immature” Chikungunya virus in which the cleavage site has been mutated to inhibit proteolysis. The spikes in the immature virus have a larger radius and are less compact than in the mature virus. Furthermore, domains B on the E2 glycoproteins have less freedom of movement in the immature virus, keeping the fusion loops protected under domain B. In addition, the nucleocapsid of the immature virus is more compact than in the mature virus, protecting a conserved ribosome-binding site in the capsid protein from exposure. These differences suggest that the posttranslational processing of the spikes and nucleocapsid is necessary to produce infectious virus.

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a mosquito-borne virus, which was first reported in Tanzania in 1952 (1) and later emerged as an epidemic in the French Reunion Island in 2005 (2). In the past decade, CHIKV has spread to more than 40 countries across Africa, Asia, and Europe, causing over a million infections in the Americas alone since 2014 (3). Among the symptoms of the disease are rash, myalgia, high fever, and, typically, severe arthritis (4).

CHIKV is a member of the alphavirus genus in the Togaviridae family (5). Other closely related and well-studied alphaviruses are Semliki Forest virus (SFV), Ross River virus (RRV), Sindbis virus (SINV), and Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis virus (VEEV). Alphaviruses are spherical enveloped viruses with an ∼700-Å diameter and a T = 4 quasi-icosahedral symmetry. The genome of alphaviruses is an ∼12-kb positive-sensed single-stranded RNA molecule encoding four nonstructural proteins (nsP1–4), which are required for virus replication, and five structural proteins (capsid protein C, glycoproteins E1, E2, E3, and 6K) (6). The structural proteins are synthesized as a long polyprotein, which is then posttranslationally cleaved into C, E1, 6K, and p62. A total of 240 copies of the C protein associate with a newly synthesized genomic RNA molecule to form a nucleocapsid in the host cell’s cytoplasm (7). The glycoproteins E1 and p62 interact to form heterodimers that subsequently trimerize into a viral spike in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The glycoprotein p62 is then cleaved into E2 and E3 by cellular furin during its transportation from the acidic environment of the Golgi and early endosomes to the neutral pH environment of the cell surface, releasing E3 (Movie S1). Virus budding occurs at the cell membrane where the nucleocapsid is enveloped by the glycoproteins E1–E2 on the plasma lipid membrane. The protein 6K facilitates particle morphogenesis (8–10), but its position in the particle remains to be verified.

Alpha- and flaviviruses (11) have many similarities. Their glycoprotein exteriors have icosahedral symmetry and surround a lipid membrane that, in turn, surrounds their RNA genome, which is associated with the capsid protein. A major difference between alpha- (12) and flaviviruses (13) is the maturation process. Flaviviruses are assembled as “immature” noninfectious particles in the ER of the host cell that are then proteolytically modified to produce infectious viruses on leaving the host cell. However, alphavirus components are proteolytically modified before assembly into mature viruses on the plasma membrane. In addition, a regular, icosahedral capsid shell is observed only in alphaviruses. During infection, a conserved sequence on the N-terminal regions of the capsid proteins binds to the host cell’s 60S ribosomal subunits, initiating the dissociation of the nucleocapsid and the release of the RNA from the nucleocapsid (14). This ribosome-binding site (RBS) is buried during nucleocapsid assembly but is exposed at the end of the maturation process (15, 16).

In alphaviruses, there are 20 trimeric spikes located on the icosahedral threefold axes and another 60 trimeric spikes in general positions that obey T = 4 quasi-symmetry (17–19). Glycoprotein E1 is involved in cell fusion (20), and glycoprotein E2 interacts with host receptors (21) whereas glycoprotein E3 facilitates E1-p62 heterodimerization and prevents the exposure of the E1 fusion loops from premature fusogenic activation (22, 23). Cryo-EM studies have shown that E3 remains associated with the mature virus of SFV (24), RRV (18), and VEEV (25). However, SINV (26, 27) and CHIKV (28) release E3 after budding.

Here, we report the structure of immature CHIKV, which was determined using virus-like particles (VLPs) with mutations at the furin cleavage site on p62. The E3 remained associated with the E2, mimicking the precursor p62 in its immature conformation. A crystal structure of the E1-p62 heterodimer [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 3N40 (29)] was fitted into the cryo-EM electron density map of immature CHIKV VLPs to examine the interactions of E1 and p62 with each other in the immature virus. A previous report showed that alphaviruses can be assembled in a partially mature, replication-competent state (25). Hence, the structure described here represents an intermediate structure of CHIKV during the assembly and maturation process. We showed that there are significant conformational differences between the mature and immature viruses, including the nucleocapsid, the transmembrane helices, and the cellular attachment sites on E2. The presence of E3 in the immature virus stabilized domain B on E2, protecting the fusion peptide on E1 from becoming exposed and fusogenic.

Results and Discussion

Cryo-EM Structure of Immature CHIKV.

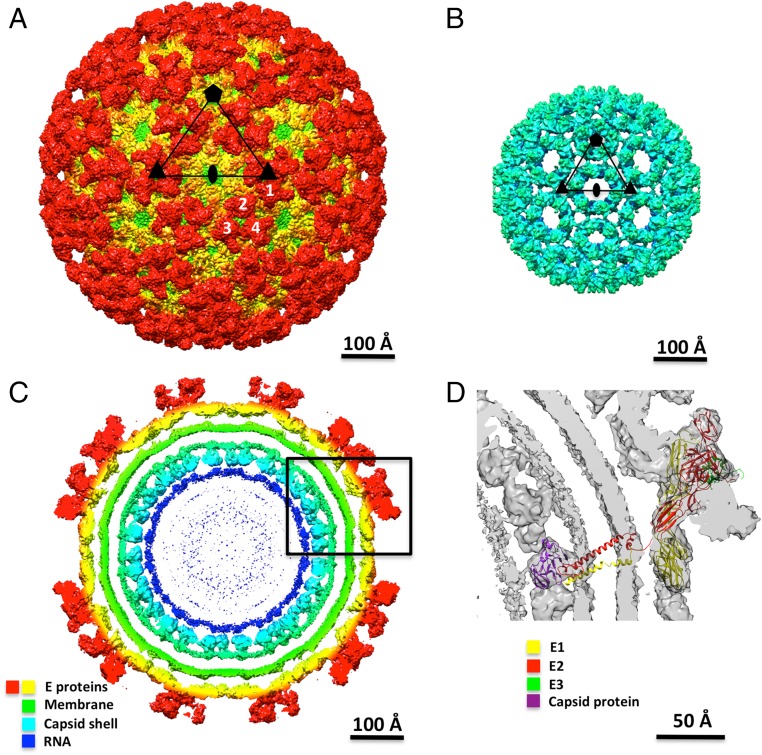

The cryo-EM density map of immature CHIK VLPs attained a 6.8-Å resolution (Fig. 1A). The virions had a diameter of 660 Å and, like mature virions, have T = 4 icosahedral symmetry. Central cross-sections of the reconstruction showed that the immature virion (Fig. 1C) has a nucleocapsid, enveloped by a plasma membrane and an outermost layer of glycoproteins. Unlike flaviruses, alphaviruses, including CHIKV, have a well-ordered icosahedral nucleocapsid within the membrane envelope (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Cryo-EM reconstruction of immature CHIK virus-like particle. (A) Three-dimensional cryo-EM map of immature CHIKV, viewed down an icosahedral twofold axis. An icosahedral asymmetric unit is marked by a black triangle. Icosahedral symmetry elements are shown as black-filled pentagon, triangles, and ellipse. Four unique subunits in an asymmetric unit are shown in white numbers. (B) Internal capsid protein shell of the immature CHIKV. (C) Central cross-sections of the immature CHIKV viewed down an icosahedral twofold axis. Components of the virus are shown in different colors as indicated in the figure. (D) Enlarged view of the region outlined by the black rectangle in C. Fitting of an E1-p62-C structure is shown in the cryo-EM map of immature CHIKV.

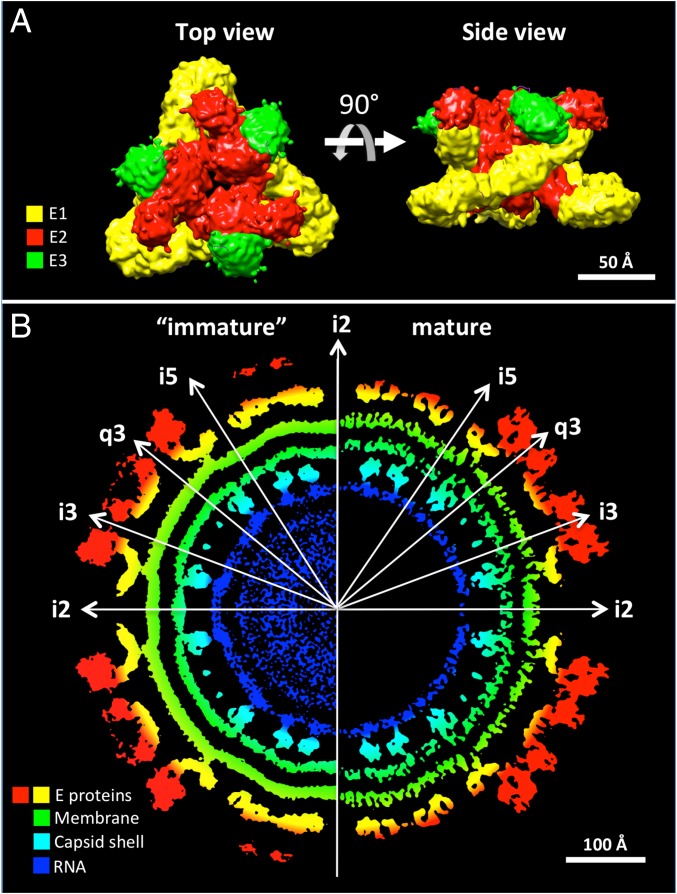

Immature CHIKV virions, like mature CHIKV virions, have spike-like features (Fig. 2A) on their surface. Intraspike contacts are formed between the three E2 molecules that form a spike. The glycoprotein E1 wraps around E2 and contributes to interspike interactions. Furthermore, E3 is located at the periphery of the E2 molecules (Fig. 2A). The trimeric immature spikes, although organized with T = 4 quasi-symmetry, are similar to mature CHIKV spikes, but are less compact with a hole along their threefold axes, resulting in a bigger spike radius. The spikes are more densely packed on the surface of immature CHIKV, resulting in smaller holes along the icosahedral twofold (i2) and icosahedral fivefold (i5) symmetry axes and smaller separation between the spikes, in comparison with mature CHIKV (Fig. 2B). Thus, the spikes undergo a structural rearrangement during maturation.

Fig. 2.

Structural characteristics of the immature CHIKV. (A) A trimeric spike of the immature CHIKV. The E2 molecules (red) form interactions within a spike whereas the E1 molecules (yellow) wrap around E2 molecules and form interactions between spikes. The E3 molecules (green) are located at the periphery of the E2 molecules. (B) Central cross-section of the immature (Left) and mature (Right) CHIKV. The icosahedral symmetry axes are indicated by white arrows. Components of the viruses are shown in different colors as indicated in the figure. The immature virus has smaller holes around the i2 and i5 symmetry axes compared to the mature virus. The diameter of the nucleocapsid in the immature virus is smaller than in the mature virus.

Glycoprotein Spikes.

As described in the crystal structure of E1-p62 (29), E1 has three beta-sheet–rich domains, namely domains I, II, and III. A fusion loop is located at the tip of domain II. E2 consists of three Ig-like domains (A, B, and C) and a long beta-ribbon (domain D) connecting domain B to C. Domain D interacts extensively with E3. The E1 fusion loop is sandwiched between domains A and B of E2.

The crystal structure of E1-p62 (PDB ID code 3N40) (29) was fitted into the cryo-EM electron density map of immature CHIKV (Fig. 1D) using the EMfit program (30). Unlike the mature CHIKV, the average electron density of domain B in E2 is higher than in the immature CHIKV (Table 1). This implies that domain B is more rigid in immature CHIKV. This result supports the hypothesis that domain B of E2 is stabilized by the presence of E3, in agreement with a previous study (29). The rigid domain B of E2 protects the fusion loop on E1 from exposure and therefore inhibits cell fusion. However, domain A of E2 is more flexible in the immature than in the mature CHIKV, as indicated by the poorer electron density (Table 1). This might be because the spikes in the immature CHIKV are less compact. Domain A of E2, which is situated close to the spike center, has fewer contacts with the neighboring molecules than in the mature virus. This domain is more stable and exposed in the mature conformation, which might be beneficial for host-cell binding.

Table 1.

Average density height of the densities at the atomic positions (sumf) on fitting of the atomic structure of CHIKV heterodimer E1-p62 into the immature cryo-EM density map

| Protein | Protein domain | T = 4 fitting | Independent molecule fitting |

| E1 | I | 14.2 | 15.3 |

| II | 14.2 | 16.0 | |

| III | 15.6 | 16.0 | |

| E2 | A | 11.1 | 13.2 |

| B | 10.0 | 11.9 | |

| C | 16.3 | 18.8 | |

| D | 13.9 | 14.1 | |

| E3 | 12.9 | 13.1 | |

| Average | 13.5 | 14.8 |

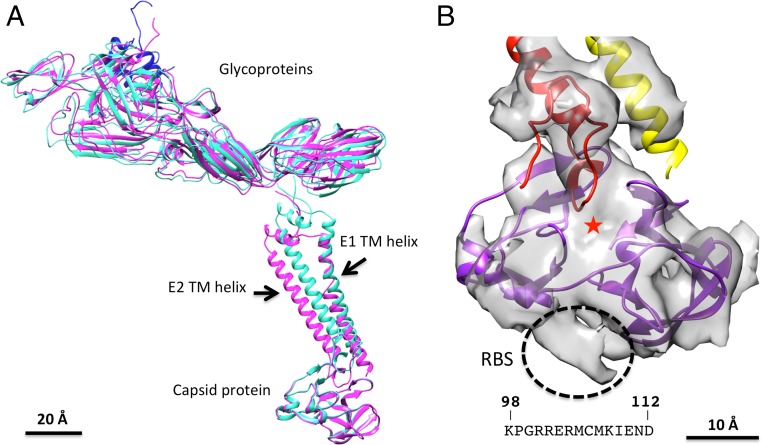

Glycoproteins Transmembrane Helices and Capsid Protein.

The chymotrypsin-like capsid protein of alphaviruses consists of a hydrophobic pocket between the two β-barrel domains (31). The rather basic N-terminal residues 1 to ∼110 of the capsid protein are disordered in the crystal structures of SINV (31, 32) and SFV (33). However, in the cryo-EM maps of VEEV and SINV, the ordered part of the capsid protein starts at about residue 109 (VEEV) (25) and residue 97 (SINV) (19), presumably due to interactions with the genomic RNA. This ordered part has a helical structure in VEEV. In the virus, the positively charged region of the capsid proteins is associated with the negatively charged RNA. The external glycoproteins and the internal capsid protein shell are associated with the E1 and E2 cytoplasmic tail binding to the capsid protein (34). This interaction has been shown to be important in virus budding and fusion (35).

The model of the E1 and E2 transmembrane (TM) domains and capsid protein as observed in mature CHIKV (28) was fitted into the cryo-EM map of immature CHIKV (Fig. 1D). There are a number of differences between the structure of immature and mature CHIKV. These include a small change in orientation and location of the TM helices (Fig. 3A and Fig. S1), resulting in a more compact nucleocapsid in the immature CHIKV (Fig. 2B). The additionally ordered amino terminal region of the capsid protein in the virus is a part of the RBS (Fig. 3B). This fragment consists of the residues 98–112 (KPGRRERMCMKIEND) of the capsid protein, which are the conserved RBS in alphaviruses (14).

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of the E1-E2-C structure in the immature and mature CHIKV. (A) Superposition of the E1-p62-C structure in the immature conformation (magenta) to E1-E2-C structure in the mature conformation (cyan). The E3 molecule in p62 is in blue. The capsid protein has a similar orientation in both immature and mature conformations. However, the TM helices have a different orientation and location in the immature form compared with the mature form. (B) Density of the capsid protein. The ordered structure of the capsid protein consists of residues 113–261. Additional density seen only in the cryo-EM reconstruction of the virus (outlined with black dashes) belongs to the N-terminal region of the capsid protein. This region is the RBS (residues 98–112). The hydrophobic pocket of the capsid protein is indicated by a red star.

The life cycle of alphaviruses can be described as starting with the mature virus in which the B domain of E2 is only loosely associated with the underlying domain II of the E1 glycoprotein. Thus, after virus recognition of a cell, the virus is enclosed into the low pH environment of an endosome. This causes the formation of trimeric fusogenic spikes resulting in the fusion of the viral and cellular membranes. As a result, the nucleocapsid is exposed to the cell’s cytoplasm containing ribosomes at low pH. The RBS on the icosahedral capsid of the mature virus is then available to bind to ribosomes. The association of ribosomes with the nucleocapsid causes the viral capsid to disintegrate (14) while guiding the genome to a ribosome. The replicated genome then associates with newly synthesized capsid proteins to make new nucleocapsids. These are transported to the plasma membrane where they will associate with mature E1–E2 to form new mature particles that bud out from the membrane. In some cases, the E3 glycoprotein, although cleaved from E2, will remain on the particle.

In the present case, the cleavage site has been mutated resulting in no cleavage of p62 but producing the assembly of immature particles. The diameter of the nucleocapsids in these immature particles is about 20 Å smaller than in the mature particles, making the particles more compact and less likely to expose the RBS. When these immature particles bind to a cell surface the (E1p62)3, trimeric spikes cannot fuse with the cell membrane because the E3 glycoprotein stops the exposure of the fusion loop. Observations of the immature particles indicate that furin cleavage of glycoprotein spikes followed by their association with the preformed nucleocapsid is required to produce fusion- and replication-competent particles.

Conclusion.

During the maturation process of alphaviruses, cleavage of p62 into E2 and E3 exposes the fusion loop on E1 and arranges the glycoprotein spikes into a mature conformation. Association of the mature spikes with the preassembled nucleocapsid expands the nucleocapsid to a less compact form. This step exposes the RBS on the capsid protein, thus priming the nucleocapsid to be disassembled upon release into the host-cell cytoplasm during the next infection cycle. The events described here for VLPs would correspond to the release of the genome into a host cell after virus entry and may be similar to the mechanism of genome release in many other viruses.

Materials and Methods

Production and Purification of Immature CHIK VLP.

The coding sequence for the CHIKV strain 37997 structural proteins, C-E3-E2-6K-E1, was synthesized by the Blue Heron Company and cloned into a pUC119-derived vector under the control of a human cytomegalovirus early immediate promoter. The expression plasmid for the furin cleavage-resistant CHIKV VLP was generated by mutating amino acids 61–64 in E3 to Ser-Gly-Gly-Gly-Gly-Ser, using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies). The VLPs were produced in FreeStyle 293-F cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were transfected with VLP-expressing plasmids by polyethylenimine reagent (Polysciences). Four days after transfection, the cell culture supernatant was harvested and clarified by centrifugation and filtration through a 0.45-µm polyethersulfone (PES) membrane. The VLPs secreted in the culture supernatant were collected by using OptiPrep Density Gradient Medium (Sigma-Aldrich), as described previously (36), and further purified by Hiprep 16/60 Sephacryl S-500 HR column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The eluates containing purified VLPs were concentrated by Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter units (EMD Millipore) and filtered with a 0.20-µm PES membrane.

Electron Microscopy and 3D Reconstruction.

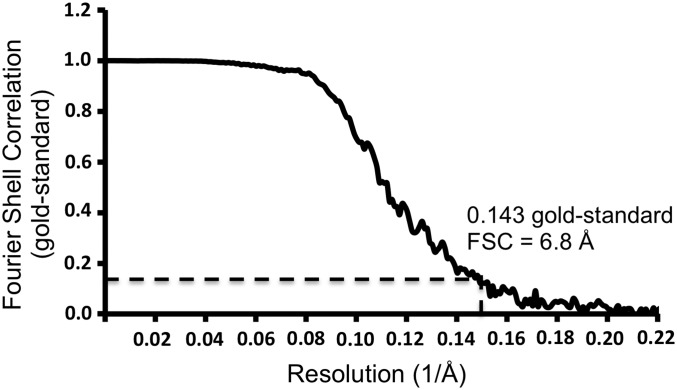

Aliquots of a 2.5-µL sample at 3 mg/mL concentration were loaded on glow-discharged C-Flat grids (CF-2/2–4C). These grids were blotted for 5 s and flash-frozen in liquid ethane using a Gatan CP3 plunge freezer. The grids were viewed using the FEI Titan Krios electron microscope operated at 300 kV. Images were recorded with a Gatan K2 Summit detector calibrated to have a magnification of 38,461, yielding a pixel size of 0.65 Å. A total dose of 36 e−/Å2 and an exposure time of 7.6 s were used to collect 38 movie frames. Fully automated data collection was implemented using Leginon (37). The MotionCorr software (38) was used to correct the beam-induced motion. A total of 5,325 images were collected, and 76,806 particles were boxed using the EMAN2 package (39). Contrast transfer function parameters were estimated using CTFFIND3 (40). The 2D classification was performed using RELION (41), and the 3D reconstruction was performed using the JSPR software (42). The final electron density map was reconstructed using 72,944 particles and was estimated to have a resolution of 6.8 Å based on the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) criterion of 0.143 (43) (Fig. 4). The map was deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (www.emdatabank.org) with Electron Microscopy Data Bank accession code EMD-8734, and structure coordinates have been deposited with the PDB (PDB ID code 5VU2).

Fig. 4.

Gold-standard FSC curve for refinement. The resolution corresponding to the 0.143 FSC cutoff is 6.8 Å.

Data Analysis and Figure Preparation.

The crystal structure of E1-p62 (PDB ID code 3N40) and models of the E1 and E2 TM domains and capsid protein (PDB ID code 3J2W) were fit into the cryo-EM map using the EMfit program (30) to maximize the average density height (sumf value) at all atomic positions. The model was fit as a rigid body using the T = 4 quasi-symmetry and also was fit independently as a rigid body into four unique positions in an asymmetric unit. All figures were prepared using Chimera (44).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sheryl Kelly and Yingyuan Sun for help in the preparation of this manuscript and technical support, respectively, and the Purdue Cryo-EM Facility for instrument access and technical support. The work was funded by NIH Grant AI095366 (to M.G.R.). Part of this work was supported by VLP Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: M.L.Y., T.K., S.S.H., and M.G.R. declare no competing financial interests. A.U. is an employee of VLP Therapeutics, and W.A. is an officer and shareholder of VLP Therapeutics.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The final immature Chikungunya VLP electron density map was deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank, https://www.emdatabank.org (accession code EMD-8734), and structure coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org/pdb (PDB ID code 5VU2).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1713166114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952-1953. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuffenecker I, et al. Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017 NOWCAST: Chikungunya in the Americas. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/modeling/index.html. Accessed April 11, 2017.

- 4.Ryman KD, Klimstra WB. Host responses to alphavirus infection. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:27–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhn RJ. Togaviridae: The viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. 5th Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 1001–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss JH, Strauss EG. The alphaviruses: Gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:491–562. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.491-562.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melancon P, Garoff H. Processing of the Semliki Forest virus structural polyprotein: Role of the capsid protease. J Virol. 1987;61:1301–1309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1301-1309.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaedigk-Nitschko K, Schlesinger MJ. The Sindbis virus 6K protein can be detected in virions and is acylated with fatty acids. Virology. 1990;175:274–281. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90209-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaedigk-Nitschko K, Schlesinger MJ. Site-directed mutations in Sindbis virus E2 glycoprotein’s cytoplasmic domain and the 6K protein lead to similar defects in virus assembly and budding. Virology. 1991;183:206–214. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90133-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanz MA, Carrasco L. Sindbis virus variant with a deletion in the 6K gene shows defects in glycoprotein processing and trafficking: Lack of complementation by a wild-type 6K gene in trans. J Virol. 2001;75:7778–7784. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7778-7784.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmaljohn AL, McClain D. Alphaviruses (Togaviridae) and Flaviviruses (Flaviviridae) In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th Ed. University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; Galveston, TX: 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jose J, Snyder JE, Kuhn RJ. A structural and functional perspective of alphavirus replication and assembly. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:837–856. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukhopadhyay S, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. A structural perspective of the flavivirus life cycle. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:13–22. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wengler G, Würkner D, Wengler G. Identification of a sequence element in the alphavirus core protein which mediates interaction of cores with ribosomes and the disassembly of cores. Virology. 1992;191:880–888. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90263-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wengler G, Wengler G, Boege U, Wahn K. Establishment and analysis of a system which allows assembly and disassembly of alphavirus core-like particles under physiological conditions in vitro. Virology. 1984;132:401–412. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wengler G. The mode of assembly of alphavirus cores implies a mechanism for the disassembly of the cores in the early stages of infection. Brief review. Arch Virol. 1987;94:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF01313721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel RH, Provencher SW, von Bonsdorff CH, Adrian M, Dubochet J. Envelope structure of Semliki Forest virus reconstructed from cryo-electron micrographs. Nature. 1986;320:533–535. doi: 10.1038/320533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng RH, et al. Nucleocapsid and glycoprotein organization in an enveloped virus. Cell. 1995;80:621–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90516-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukhopadhyay S, et al. Mapping the structure and function of the E1 and E2 glycoproteins in alphaviruses. Structure. 2006;14:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lescar J, et al. The fusion glycoprotein shell of Semliki Forest virus: An icosahedral assembly primed for fusogenic activation at endosomal pH. Cell. 2001;105:137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith TJ, et al. Putative receptor binding sites on alphaviruses as visualized by cryoelectron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10648–10652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulvey M, Brown DT. Involvement of the molecular chaperone BiP in maturation of Sindbis virus envelope glycoproteins. J Virol. 1995;69:1621–1627. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1621-1627.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carleton M, Lee H, Mulvey M, Brown DT. Role of glycoprotein PE2 in formation and maturation of the Sindbis virus spike. J Virol. 1997;71:1558–1566. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1558-1566.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mancini EJ, Clarke M, Gowen BE, Rutten T, Fuller SD. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals the functional organization of an enveloped virus, Semliki Forest virus. Mol Cell. 2000;5:255–266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang R, et al. 4.4 Å cryo-EM structure of an enveloped alphavirus Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. EMBO J. 2011;30:3854–3863. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paredes AM, et al. Three-dimensional structure of a membrane-containing virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9095–9099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paredes AM, et al. Structural localization of the E3 glycoprotein in attenuated Sindbis virus mutants. J Virol. 1998;72:1534–1541. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1534-1541.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun S, et al. Structural analyses at pseudo atomic resolution of Chikungunya virus and antibodies show mechanisms of neutralization. Elife. 2013;2:e00435. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voss JE, et al. Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature. 2010;468:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossmann MG, Bernal R, Pletnev SV. Combining electron microscopic with x-ray crystallographic structures. J Struct Biol. 2001;136:190–200. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2002.4435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S, et al. Identification of a protein binding site on the surface of the alphavirus nucleocapsid and its implication in virus assembly. Structure. 1996;4:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi HK, et al. Structure of Sindbis virus core protein reveals a chymotrypsin-like serine proteinase and the organization of the virion. Nature. 1991;354:37–43. doi: 10.1038/354037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi HK, Lu G, Lee S, Wengler G, Rossmann MG. Structure of Semliki Forest virus core protein. Proteins. 1997;27:345–359. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199703)27:3<345::aid-prot3>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owen KE, Kuhn RJ. Alphavirus budding is dependent on the interaction between the nucleocapsid and hydrophobic amino acids on the cytoplasmic domain of the E2 envelope glycoprotein. Virology. 1997;230:187–196. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang J, et al. Molecular links between the E2 envelope glycoprotein and nucleocapsid core in Sindbis virus. J Mol Biol. 2011;414:442–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akahata W, et al. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med. 2010;16:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nm.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suloway C, et al. Automated molecular microscopy: The new Leginon system. J Struct Biol. 2005;151:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X, et al. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nat Methods. 2013;10:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang G, et al. EMAN2: An extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2003;142:334–347. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheres SH. A Bayesian view on cryo-EM structure determination. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo F, Jiang W. Single particle cryo-electron microscopy and 3-D reconstruction of viruses. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1117:401–443. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-776-1_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheres SH, Chen S. Prevention of overfitting in cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods. 2012;9:853–854. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera: A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.