Significance

Antimicrobial drug resistance is set to kill millions in the coming decades. Finding new drugs is one solution, but might it also be possible to prevent the emergence of drug resistance in the first place? We show that the emergence of drug resistance can be prevented by reducing the availability of a nutrient for which drug-resistant parasites are especially hungry. Rather than killing parasites, this intervention works by harnessing ecological interactions: With resistant parasites struggling to replicate, susceptible parasites outcompete them before they can emerge. Since resource-limiting drugs can be rationally designed and do not need to be lethal, it may be easier to find them than new, traditional drugs.

Keywords: drug resistance, competition, combination therapy, Plasmodium chabaudi, evolutionary management

Abstract

Slowing the evolution of antimicrobial resistance is essential if we are to continue to successfully treat infectious diseases. Whether a drug-resistant mutant grows to high densities, and so sickens the patient and spreads to new hosts, is determined by the competitive interactions it has with drug-susceptible pathogens within the host. Competitive interactions thus represent a good target for resistance management strategies. Using an in vivo model of malaria infection, we show that limiting a resource that is disproportionately required by resistant parasites retards the evolution of drug resistance by intensifying competitive interactions between susceptible and resistant parasites. Resource limitation prevented resistance emergence regardless of whether resistant mutants arose de novo or were experimentally added before drug treatment. Our work provides proof of principle that chemotherapy paired with an “ecological” intervention can slow the evolution of resistance to antimicrobial drugs, even when resistant pathogens are present at high frequencies. It also suggests that a broad range of previously untapped compounds could be used for treating infectious diseases.

Drug resistance threatens modern medicine as we know it (1, 2). Since the rate that new antimicrobials are being discovered has declined (3), there is an urgent need to develop interventions that slow the evolution of resistance to drugs that remain effective, as well as to next-generation antimicrobials (4, 5).

At its simplest, drug resistance evolution is a two-step process. First, an individual pathogen must acquire a genetic change that confers resistance to drugs. Second, the progeny of that resistant pathogen must successfully emerge, reaching high densities within the host. In the absence of drug treatment, resistant pathogens rarely emerge because they experience intense competition from susceptible competitors (competitive suppression), such as the ancestors that gave rise to them, particularly when resistance is associated with fitness costs (6, 7). Drug treatment removes susceptible competitors, allowing resistant pathogens to flourish, a phenomenon known as competitive release (8–10). Ecological theory predicts that when an organism requires more of a limiting resource to survive than its competitor, depleting that resource from the environment will tip the competitive scales in favor of the organism’s competitor (11–13). When drug resistance is associated with elevated resource requirements, as in some malaria parasites (14, 15) and bacteria (16, 17), resource limitation could therefore intensify the competitive suppression of resistant mutants. If the competition can be sufficiently intensified, it might be possible to eliminate resistant pathogens before their susceptible competitors are removed by drugs.

We tested this idea using the malaria mouse model, Plasmodium chabaudi, the drug pyrimethamine, and the nutrient para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA). P. chabaudi parasites resistant to pyrimethamine require more pABA than susceptible parasites (18) and suffer intense competitive suppression from susceptible competitors, particularly when pABA is scarce (19). We hypothesized that in pABA-limited mice, it would be possible to both treat the infection and prevent the emergence of drug resistance.

Results

Two hundred mice were inoculated with 106 parasites of a pyrimethamine-susceptible strain of P. chabaudi and treated with a week-long regimen of high-dose pyrimethamine treatment (Fig. 1A). Treatment began 6 d after inoculation, when mice begin to exhibit symptoms. Half of the mice were supplemented with pABA, as is standard in experimental studies of mouse models of malaria, (20, 21), and half were not. On the day before drug treatment began, there was no difference in the size of the parasite populations of pABA-supplemented and pABA-limited mice (Fig. S1).

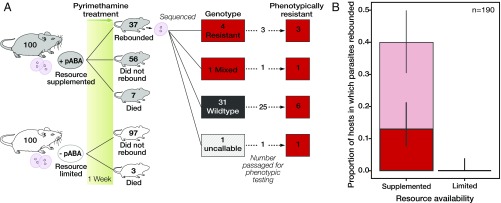

Fig. 1.

Resource limitation prevents the emergence of drug resistance. (A) Mice were assigned to each resource treatment and inoculated with 106 pyrimethamine-susceptible parasites. Rebounding parasite populations were genotyped (Fig. S3) and injected into a second drug-treated mouse to assess their phenotypic resistance. All parasites that were genotypically resistant and underwent phenotypic testing were found to be phenotypically resistant. (B) Proportion of mice in which parasites rebounded (light red, thin-lined bar) and which were confirmed to be either genetically or phenotypically resistant (dark red, thick-lined bar). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval around the proportion as calculated from a binomial distribution. n, number of mice included in the analysis.

In the pABA-supplemented treatment, parasites rebounded following drug treatment in 37 of 93 (40%) mice; parasites of 12 of these mice were confirmed to be either phenotypically or genotypically resistant (Fig. 1 and SI Discussion). In sharp contrast, parasites did not rebound following drug treatment in mice not given pABA. Thus, resource limitation completely prevented the emergence of drug resistance (Fig. 1).

To confirm that resource limitation prevented resistance emergence by intensifying the competitive suppression of drug-resistant parasites, and that the effect was not contingent on some unknown effect of pABA limitation on the rate that de novo resistance mutations occur, we investigated the effect of pABA limitation on resistance emergence in mice infected with both a resistant strain and a susceptible competitor and in mice infected with the resistant strain alone. Coinfected mice were first inoculated with 106 parasites of a drug-susceptible strain; then, on the day before drug treatment began, all mice were infected with 105 parasites of a drug-resistant strain.

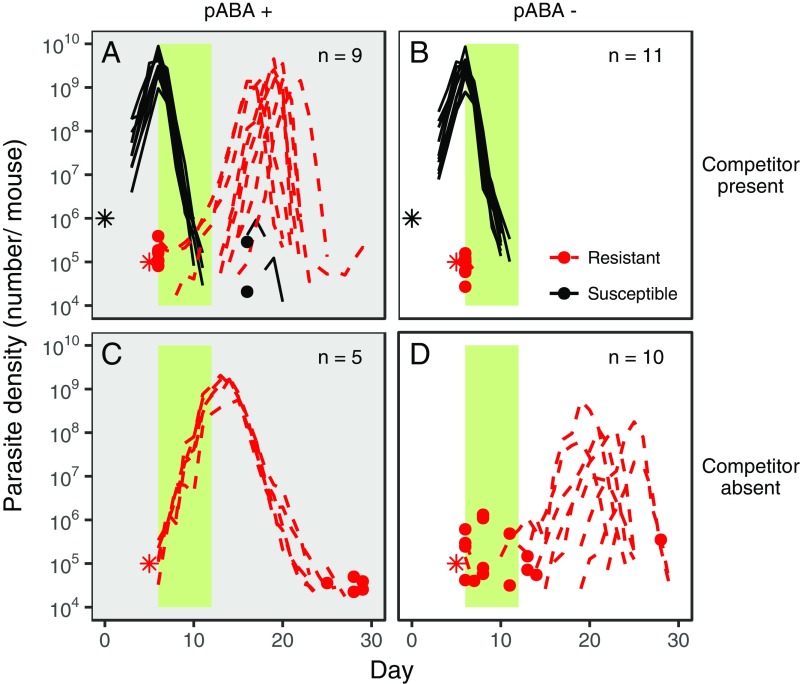

Following drug treatment, resistant parasites emerged in all of the coinfected, pABA-supplemented mice (Fig. 2A and Table S1), reaching a density of more than 109 resistant parasites per mouse (Fig. 2A). In contrast, resistant parasites were not observed following drug treatment in any of the coinfected mice in the pABA-limited treatment (Fig. 2B and Table S1). Limitation of pABA prevented the emergence of drug resistance by intensifying competitive suppression since resistant parasites grew to high densities in almost all of the pABA-limited mice that were infected with resistant parasites but not with a susceptible competitor (Fig. 2D, Table S1, and SI Discussion). Resource limitation made coinfected mice less anemic (Fig. 3 A and B) and eliminated the possibility of the onward transmission of drug-resistant parasites (Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 2.

Resource limitation prevents the emergence of drug resistance by intensifying competitive suppression. Dynamics of pyrimethamine-susceptible (black, solid lines) and -resistant (red, dashed lines) parasites in mice given supplemental pABA (A and C; gray background) or not (B and D; white background) and infected with both susceptible and resistant parasites (A and B) or with only resistant parasites (C and D) are shown. Each line represents the dynamics of parasites in an individual mouse. The infection dynamics of each mouse are plotted in Figs. S4–S6. Stars indicate the number and timing at which parasites were inoculated; note that resistant parasites enter the host at a much greater frequency than a de novo mutant would. Dots indicate the density of parasites detected on a particular day in instances where parasites were not detected the day before or after, and the green bar represents the period of pyrimethamine treatment. n, number of mice included in the analysis. Susceptible and resistant parasites were of the AJ and AS genetic backgrounds (SAJ and RAS), respectively; only resistant parasites possess the S106N mutation associated with pyrimethamine resistance in P. chabaudi (Fig. S7). In the absence of drugs, resistant parasites were competitively suppressed by susceptible parasites and did not emerge in either resource treatment (Fig. S8).

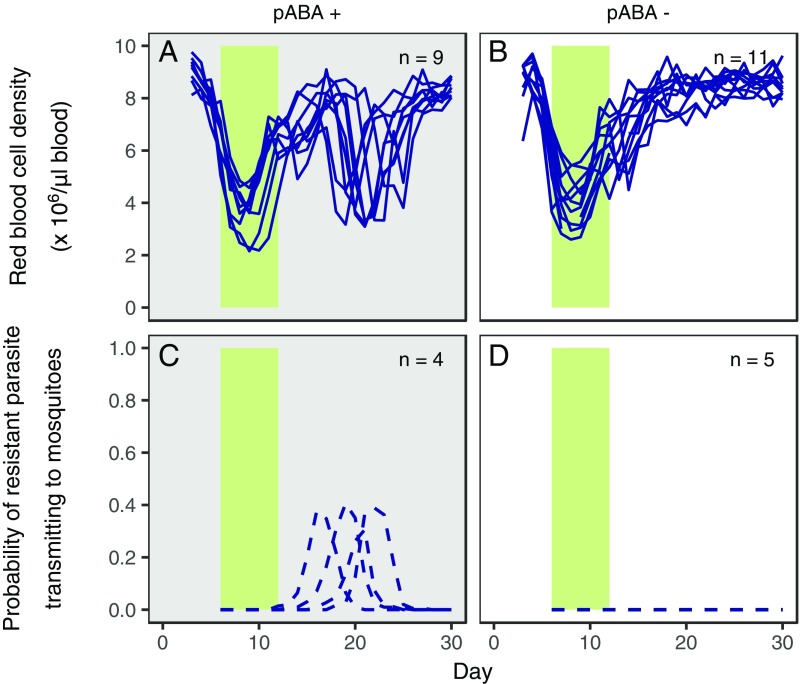

Fig. 3.

Resource limitation improves host health and prevents the transmission of drug resistance in mice inoculated with both drug-susceptible and drug-resistant parasites. Red blood cell dynamics of individual mice (A and B; solid lines) and the probability of resistant parasites transmitting to mosquitoes (C and D; dashed lines) in mice infected with both susceptible and drug-resistant parasites (SAJ and RAS) and either supplemented with resources (A and C; gray background, pABA+) or not (B and D; white background, pABA−) are shown. All mice were administered pyrimethamine treatment (green bar). Limitation of pABA was associated with less anemia (total red blood cell density, resource treatment: F1,17 = 24.3; P < 0.001, linear regression). Note that these data are from all (A and B) or a subset (C and D) of the infections shown in Fig. 2 A and B.

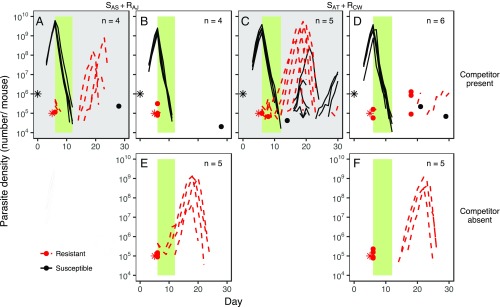

In two follow-up experiments, we examined the effect of pABA limitation on resistance emergence in mice infected with other pairs of parasite strains, almost doubling the number of replicates in the resource limitation treatment (Table S1). Limitation of pABA prevented the emergence of drug-resistant parasites in all but one of the 10 mice coinfected with drug-resistant and drug-susceptible parasites (Fig. 4 A–D and Table S1) but did not prevent their proliferation in seven of the 10 mice that were infected with resistant parasites only (Fig. 4 E and F). Taken together, our data (Figs. 2 and 4) show that resource limitation reduces resistance emergence by intensifying within-host competition, even when resistant parasites are present at an initial density many orders of magnitude greater than the density of a de novo resistant mutant when it first arises.

Fig. 4.

Resource limitation prevents the emergence of drug-resistant parasites, irrespective of the combination of strains with which the host is infected. Dynamics of susceptible (black, solid lines) and pyrimethamine-resistant (red, dashed lines) parasites in mice coinfected with SAS and RAJ (A and B), SAT and RCW (C and D), or only RAJ (E) or RCW (F), and either administered resources (A and C; gray background) or not (B and D–F; white background) are shown. The resistant strains (RAJ and RCW), but not the susceptible strains (SAS and SAT), possess the mutation associated with pyrimethamine resistance in this system (Fig. S7). Each line represents the dynamics of infections in an individual mouse; the infection dynamics of each mouse are plotted separately in Fig. S9. Stars represent the number of parasites inoculated and the time at which they were administered. Dots indicate the density of parasites detected on a particular day in instances where parasites were not detected the day before or after. The green bar indicates the duration and timing of pyrimethamine treatment. n, number of mice plotted and included in the analysis. Note that in these experiments, unlike those in Fig. 2, resistant parasites were not grown alone in pABA-supplemented mice.

Discussion

Our data provide proof of principle that competitive interactions between pathogens can be manipulated to prevent the emergence of antimicrobial resistance by reducing the availability of within-host resources. Resource limitation could be achieved through dietary intervention, as modeled in our experiments, or by a broad range of compounds, such as chelators, (artificial) siderophores, inhibitors of host pathways that produce resources used by parasites, and drugs that deplete resources from the host environment either directly or as a side effect. Many examples of the latter are already approved for human use (22, 23). We suggest that it should therefore be possible to partner a traditional antimicrobial drug with a resource-limiting drug so as to prolong the useful life span of the antimicrobial drug.

A combination of a traditional antimicrobial and a resource-limiting drug may be more robust to resistance evolution than traditional combination therapy, as resistance to resource-limiting drugs may emerge more slowly than to conventional drugs. First, a variety of mechanisms that confer resistance to traditional antimicrobial drugs (either -cidal or -static), such as mutations at drug-binding sites and expression of efflux pumps, will not confer resistance to resource limitation. With fewer pathways available to confer resistance to resource limitation, we might expect resistance to resource limitation to evolve more slowly than resistance to a traditional antimicrobial partner drug. Second, with judicious choice of which resource to manipulate, it may be possible to greatly weaken the strength of selection for resistance and even to focus it entirely on a small part of the parasite population. For instance, where resource limitation has little impact on the susceptible parasite population, as was the case here (Fig. S2), selection for resistance to resource limitation will be restricted to the small subset of the population that is resistant to the traditional antimicrobial in the combination—only in this population will resistance to resource limitation be advantageous. As such, resource limitation could offer similar resistance management advantages as compounds that specifically target resistant pathogens (5, 24, 25).

This ecological approach to resistance management opens up the possibility of using hitherto untapped compounds for drug treatment. Resource-limiting drugs will have a different profile than standard chemotherapeutics, in that they should target the host environment and could be negligibly toxic to the pathogen (as pABA limitation was; Figs. 2D, 4 E and F, and Fig. S2). Therefore, resource-limiting drugs may not be detected in standard drug discovery screens aimed at identifying toxic compounds. Nevertheless, there is considerable scope for the rational discovery of resource-limiting drugs. By studying resistance to conventional antimicrobial drugs both before and after they are on the market (e.g., refs. 24, 26–28), resource contingencies associated with drug resistance can be identified and resource-limiting interventions could be designed to protect traditional chemotherapeutic agents. Since drug resistance is associated with elevated resource requirements in some cancers (29, 30), resource limitation may also be of relevance to the management of drug resistance in cancer cells. Whatever the target organism, it will be crucial that screening for a resource-limiting compound involves ecological assays, whereby the impact of resource limitation on the intensity of competitive interactions between drug-susceptible and drug-resistant parasites is assessed.

Materials and Methods

Study Design.

To investigate if and how resource limitation could slow the emergence of drug resistance, we performed four experiments. In experiment 1, we investigated the impact of resource limitation on the emergence of pyrimethamine resistance in mice infected with a pyrimethamine-susceptible strain of P. chabaudi. In experiments 2–4, we investigated the impact of resource limitation on the competitive release of pyrimethamine-resistant parasites in mice infected with both pyrimethamine-susceptible and pyrimethamine-resistant strains of P. chabaudi, which differed in their genetic backgrounds (Table S1). To ensure that our results were not driven by the genetic backgrounds of the strains, we used a different combination of parasite strains in each of experiments 2–4 (Table S1): In experiment 2, we used drug-susceptible strains of the AJ genetic background and a pyrimethamine-resistant strain with the AS background; in experiment 3, we reversed the design of experiment 2, using susceptible parasites with the AS background and a pyrimethamine-resistant strain of the AJ background; and in experiment 4, we used sensitive parasites with the AT background and resistant parasites with the CW background. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Pennsylvania State University (permit no. 44512).

Experiment 1.

Hosts and parasites.

A total of 200 inbred Swiss Webster mice were maintained on 5001 Laboratory Rodent Diet (LabDiet). Parasites in this and all other experiments were of the species P. chabaudi, originally isolated from thickets rats, Thamnomys rutilans. Each mouse was inoculated i.p. with 106 parasites of the pyrimethamine-susceptible AS13p strain. This strain, which had never previously been exposed to pyrimethamine, is susceptible to pyrimethamine and does not possess the mutation associated with pyrimethamine resistance in P. chabaudi (Genotypic assessment of rebounding parasites and Fig. S3). Half of the mice received a 0.05% pABA solution, made with diH2O as the solvent, as drinking water from the day before parasite inoculation (resource-supplemented treatment), and the remaining half received diH2O only (resource-limited treatment). Five days following parasite inoculation, 5 μL of blood was taken from the tail for the quantitation of parasite density (Infection monitoring). Between days 6 and 12 postinoculation (PI), mice received pyrimethamine at a dose of 8 mg/kg twice a day by i.p. injection, for a total of 14 treatments. Pyrimethamine treatment was initiated on day 6 PI, when mice typically begin to exhibit symptoms (Fig. 3 A and B), to reflect the fact that patients seek treatment upon feeling sick. From day 13 to day 26 PI, blood was taken daily from the tail, a slide was made, and the presence of parasites in the blood was assessed by microscopy. If parasites were observed, the parasites were said to have rebounded. The author (D.G.S.) who performed the drug treatment, microscopy, and subsequent passages (Phenotypic assessment of rebounding parasites) was blinded to the resource treatment to which mice were assigned.

Phenotypic assessment of rebounding parasites.

When parasites were observed in the blood after pyrimethamine treatment had ended, 106 parasites were passaged onto one or two “secondary mice,” which were administered pyrimethamine at a dose of 8 mg/kg immediately after they were inoculated with parasites. Treatments continued twice a day until the mouse had received 14 doses in total. On the day after the last dose of pyrimethamine, blood was examined for parasites, as described above. If parasites were found, they were classified as phenotypically drug resistant; 10 μL of blood was taken from the tail for genotypic analysis of the parasites and a further sample was frozen down in liquid nitrogen.

Genotypic assessment of rebounding parasites.

In P. chabaudi, pyrimethamine resistance is most commonly conferred by a mutation from guanine to adenine that causes an amino acid change from serine to asparagine at position 106 of the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) gene (31–33). This is the P. chabaudi version of the Plasmodium falciparum S108N mutation (33). We assessed whether the S106N mutation was present in the parasites that emerged in primary mice following drug treatment in experiment 1, as well as in the original inoculum of AS13p (Fig. S3). DNA was extracted from the samples taken upon parasite emergence, as described above. Primers DHFR-F, AAG GGA CTT GGG AAT GAA GG, and DHFR-R, CAG ATG CAC CTC CTA TAA CAA AA, were used at a final concentration of 400 nM; they were designed using Primer3 software (34, 35). PCR was performed using the Taq PCR Core Kit (Qiagen) under the following conditions: 94 °C for 2 min and 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 10 min. The resulting product of 400 bp was purified using the E.Z.N.A. Gel Extraction Kit (OMEGA Bio-Tek) before being sequenced in both directions by the Penn State Genomics Core Facility. Consensus contigs were assembled and aligned to a pyrimethamine-susceptible reference sequence [GenBank accession no. L28120.1 (33) (Fig. S3) using GENEIOUS (version 10) (36)]. The presence of the S106N mutation in the sequences was assessed by visual inspection of chromatograms, and the results of this analysis were corroborated by the calls made by GENEIOUS. In one case, dual peaks were observed, and this base was called as “mixed” (Fig. 1A and Fig. S3, sequence fifth from bottom).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using R (version 3.2.0). The impact of resource treatment on parasite density on day 5 was analyzed using Welch’s two-sided t test. Parasite density was log-transformed before analysis.

Competition Experiments (Experiments 2, 3, and 4).

The impact of resource limitation on the competitive suppression and release of pyrimethamine-resistant parasites was investigated by comparing the performance of pyrimethamine-resistant parasites in the absence (single infections) and presence of competition from a genetically distinct drug-susceptible parasite strain (mixed infections) in mice either supplemented with 0.05% pABA (resource-supplemented treatment) or not (resource-limited treatment) (Table S1). Mice in mixed-infection treatments were inoculated with 106 susceptible parasites on day 0 and 105 resistant parasites on day 5. Mice in single-infection treatments were inoculated with either 106 susceptible parasites on day 0 or 105 resistant parasites on day 5. Since the detection threshold of quantitative PCR (qPCR) is ∼200 parasites per microliter (which equates to ∼104 parasites in a 20-g mouse) (37), inoculating 105 resistant parasites enabled us to confirm that resistant parasites had been present in cases where they did not emerge posttreatment.

Hosts and parasites.

Hosts in all experiments were inbred female C57BL/6 mice maintained on 5001 Laboratory Rodent Diet. Mice in the resource-supplemented treatment were administered 0.05% pABA from the day before they were inoculated with parasites. In each experiment, a different pair of pyrimethamine-susceptible and -resistant strains was used. In block 1 of experiment 2, the drug-susceptible strain AJ22p and pyrimethamine-resistant strain AS123p (RAS) were used; in block 2, AJ35p was used in place of AJ22p, from which AJ35p is descended (both are referred to hereafter and in the figures as SAJ). In experiments 3 and 4, the strain pairs AS13p (SAS) and AJ36p (RAJ) and AT2p (SAT) and CW29p (RCW) were used, respectively. Whereas the drug-resistant ancestor of RAS was derived by passage from 47AS, a strain made resistant to pyrimethamine by a single round of drug selection (38), we created RAJ and RCW by drug selection, as described below. The presence of the S106N mutation in the DHFR gene of all strains was confirmed by sequencing, following the protocol described above (Fig. S7).

Selection of pyrimethamine-resistant strains for experiments 3 and 4.

For experiments 3 and 4, we created pyrimethamine-resistant strains with CW and AJ genetic backgrounds by in vivo drug selection. Selection for resistance to pyrimethamine was imposed on strains CW28 and AJ35p, which had never been exposed to pyrimethamine, following the protocol used in experiment 1. Each strain was administered to 10 outbred Swiss mice, which were maintained on PicoLab Rodent Diet 5053 (LabDiet) and 0.05% pABA solution. As soon as parasites were detected in the blood posttreatment, ∼106 parasites were passaged to each of four additional mice, which immediately received pyrimethamine drug treatment. As soon as parasitemia reached 30% in a mouse, parasites were frozen down for storage in liquid nitrogen, as CW29p (RCW) and AJ36p (RAJ). The presence of the S106N mutation in these strains was latterly confirmed (discussed above).

Drug treatment.

Pyrimethamine dissolved in DMSO was administered to mice at a dose of 8 mg/kg 11 times between days 6 and 12 (twice daily on days 6–9, once daily on days 10–12). In block 1 of experiment 2, where pyrimethamine was administered in a 0.05-mL volume of DMSO, mortality was higher in treated groups than in untreated groups. We reasoned that this was because of the toxic effects of DMSO and so used an injection volume of 0.03 mL in experiments 3 and 4. Since patients who do not receive drug treatment are spared its toxic side effects, mice in untreated groups were given an injection of saline equal in volume to that given to treated mice.

Infection monitoring.

Between days 3 and 30 PI, 7 μL of blood was taken from the tail: 5 μL for quantification of asexual parasite density using qPCR and 2 μL for the quantification of red blood cell density using a Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter). Asexual parasite density was quantified as previously described (37), with the exception that parasite DNA was extracted using a MagMax 96 DNA Multi-Sample Kit (Life Technologies), per the manufacturer’s instructions. In block 1 of experiment 2, an additional 10 μL was taken for the quantification of gametocytes (transmission stages) following the method of Huijben et al. (39).

Experiment 2: Block 1.

To explore the impact of resource availability, pyrimethamine treatment, and competition on the dynamics of pyrimethamine-resistant and -susceptible parasite infections, we performed a fully factorial experiment (Table S1). Each treatment group contained five mice, with three exceptions. Eight mice were allocated to the resource-supplemented, mixed-infection group that did not receive pyrimethamine treatment, as these mice were expected to experience higher than average mortality. Eight mice were allocated to each of the pABA-limited, mixed-infection groups (one of which received pyrimethamine treatment) to guard against resistant parasites failing to take hold in these treatments.

Experiment 2: Block 2.

To replicate key findings from block 1, we repeated a subset of the treatments from block 1 in block 2 (Table S1). To confirm the impact of resource limitation on competitive release, both the resource-limited and resource-supplemented, drug-treated, mixed-infection groups were repeated. To further confirm that resource limitation acts via its impact on competitive interactions, rather than being lethal to resistant parasites, we repeated the resource-limited, drug-treated, single resistant infection group.

Experiments 3 and 4.

These experiments had the same design as that of block 2 of experiment 2 (Table S1).

Statistical analysis.

We calculated total parasite density and red blood cell density (the sum of these measurements over the course of the experiment). To examine the impact of resource limitation on resistant and susceptible parasite strains in block 1 of experiment 2, we used a generalized least squares model with experimental treatment specified as a variance covariate to account for heterogeneity in the variance in total parasite density among treatments and for resource treatment, strain, and their interaction as predictors. For the analysis of red blood cell density, standard linear regression was used and block was included as a main effect to control for possible block by block variation. Least significant terms were dropped from the full model until all predictors were significant. Parasite density was log-transformed before analysis to meet the assumptions of the model.

The probability of parasites transmitting to mosquitoes was calculated using the gametocyte density-infectivity function derived experimentally by Bell et al. (40).

Mice that died, received a dose of parasites lower than was intended, or were inadvertently given drug treatment were excluded from the analysis (Figs. S4–S6 and S9 and Table S1).

Graphics.

To ease interpretation, parasite densities were converted to numbers per mouse under the assumption that a mouse has 58.5 mL of blood per kilogram of weight and weighs 20 g. The y-axis limit is set to 104 to reflect the detection limit of the qPCR assay used to measure parasite densities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Read and Thomas groups for discussion and A. King, M. Duffy, D. Goldberg, N. Mideo, E. Hansen, K. Vandegrift, and M. Acosta for comments on the manuscript. We thank J. Megahan for assistance with Fig. 1A. This work was funded by the Institute of General Medical Science (Grant R01 GM089932). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The datasets generated during this study are available from the Dryad Digital Depository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.v2q3v).

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1715874115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2016 Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Available at https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2017.

- 2.Laxminarayan R, et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: A worldwide challenge. Lancet. 2016;387:168–175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown ED, Wright GD. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolgin E. Inner workings: Combating antibiotic resistance from the ground up. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:11642–11643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614173113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baym M, Stone LK, Kishony R. Multidrug evolutionary strategies to reverse antibiotic resistance. Science. 2016;351:aad3292. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babiker HA, Hastings IM, Swedberg G. Impaired fitness of drug-resistant malaria parasites: Evidence and implication on drug-deployment policies. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7:581–593. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson DI, Hughes D. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: Is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:260–271. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wargo AR, Huijben S, de Roode JC, Shepherd J, Read AF. Competitive release and facilitation of drug-resistant parasites after therapeutic chemotherapy in a rodent malaria model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19914–19919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707766104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Read AF, Day T, Huijben S. The evolution of drug resistance and the curious orthodoxy of aggressive chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10871–10877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100299108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day T, Huijben S, Read AF. Is selection relevant in the evolutionary emergence of drug resistance? Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tilman D. Resource Competition and Community Structure. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tilman EA, Tilman D, Crawley MJ, Johnston AE. Biological weed control via nutrient competition: Potassium limitation of dandelions. Ecol Appl. 1999;9:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith VH, Holt RD. Resource competition and within-host disease dynamics. Trends Ecol Evol. 1996;11:386–389. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)20067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs RL. Role of p-aminobenzoic acid in Plasmodium berghei infection in the mouse. Exp Parasitol. 1964;15:213–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(64)90017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang P, Nirmalan N, Wang Q, Sims PFG, Hyde JE. Genetic and metabolic analysis of folate salvage in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;135:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiefer P, et al. Metabolite profiling uncovers plasmid-induced cobalt limitation under methylotrophic growth conditions. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song T, et al. Fitness costs of rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis are amplified under conditions of nutrient starvation and compensated by mutation in the β′ subunit of RNA polymerase. Mol Microbiol. 2014;91:1106–1119. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wernsdorfer WH, Trigg PI. Recent progress of malaria research: Chemotherapy. In: Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor IA, editors. Malaria: Principles and Practice of Malariology. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1988. pp. 1569–1674. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wale N, Sim DG, Read AF. A nutrient mediates intraspecific competition between rodent malaria parasites in vivo. Proc Biol Sci. 2017;284:20171067. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walliker D, Carter R, Morgan S. Genetic recombination in Plasmodium berghei. Parasitology. 1973;66:309–320. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000045248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor LH, Walliker D, Read AF. Mixed-genotype infections of malaria parasites: Within-host dynamics and transmission success of competing clones. Proc Biol Sci. 1997;264:927–935. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stargrove MB, Treasure J, McKee DL. Herb, Nutrient, and Drug Interactions: Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Strategies. Mosby Elsevier; St. Louis: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwegmann A, Brombacher F. Host-directed drug targeting of factors hijacked by pathogens. Sci Signal. 2008;1:re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.129re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukens AK, et al. Harnessing evolutionary fitness in Plasmodium falciparum for drug discovery and suppressing resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:799–804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320886110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright GD. Antibiotic adjuvants: Rescuing antibiotics from resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:862–871. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou T, Zhang W, Wang J, Wang W. Predicting drug resistance of the HIV-1 protease using molecular interaction energy components. Proteins. 2009;74:837–846. doi: 10.1002/prot.22192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corey VC, et al. A broad analysis of resistance development in the malaria parasite. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11901. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sommer MOA, Munck C, Toft-Kehler RV, Andersson DI. Prediction of antibiotic resistance: Time for a new preclinical paradigm? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:689–696. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva AS, et al. Evolutionary approaches to prolong progression-free survival in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6362–6370. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stäubert C, et al. Rewired metabolism in drug-resistant leukemia cells: A metabolic switch hallmarked by reduced dependence on exogenous glutamine. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:8348–8359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.618769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sirawaraporn W, Yuthavong Y. Kinetic and molecular properties of dihydrofolate reductase from pyrimethamine-sensitive and pyrimethamine-resistant Plasmodium chabaudi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1984;10:355–367. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(84)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowman AF, Lew AM. Chromosomal rearrangements and point mutations in the DHFR-TS gene of Plasmodium chabaudi under antifolate selection. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;42:21–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Q, Saul A. The dihydrofolate reductase domain of rodent malarias: Point mutations and pyrimethamine resistance. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;65:361–363. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Untergasser A, et al. Primer3–New capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1289–1291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kearse M, et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell AS, de Roode JC, Sim D, Read AF. Within-host competition in genetically diverse malaria infections: Parasite virulence and competitive success. Evolution. 2006;60:1358–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walliker D, Carter R, Sanderson A. Genetic studies on Plasmodium chabaudi: Recombination between enzyme markers. Parasitology. 1975;70:19–24. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000048824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huijben S, et al. Chemotherapy, within-host ecology and the fitness of drug-resistant malaria parasites. Evolution. 2010;64:2952–2968. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell AS, et al. Enhanced transmission of drug-resistant parasites to mosquitoes following drug treatment in rodent malaria. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.