Abstract

Human onchocerciasis—commonly known as river blindness—is one of the most devastating yet neglected tropical diseases, leaving many millions in Sub-Saharan Africa blind and/or with chronic disabilities. Attempts to eliminate onchocerciasis, primarily through the mass drug administration of ivermectin remains challenging and has been heightened by the recent news that drug-resistant parasites are developing in some populations after years of drug treatment. Needed, and needed now, in the fight to eliminate onchocerciasis are new tools, such as preventive and therapeutic vaccines. This review summarizes the progress made to advance the onchocerciasis vaccine from the research lab into the clinic.

Descriptive words: Onchocerca volvulus, vaccine, vaccine candidates, elimination

Why a vaccine against Onchocerca volvulus is needed

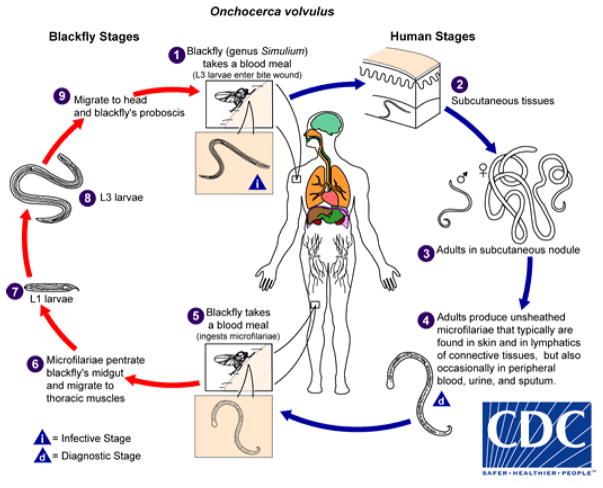

Human onchocerciasis caused by Onchocerca volvulus and spread by the bite of infected Simulium black flies (Figure 1) remains one of the most important neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). Recent estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 indicate that approximately 15.5 million people currently live with onchocerciasis, including 12.2 million people with Onchocerca skin disease (OSD) and 1.025 million with vision loss (river blindness) [1]. Almost everyone severely affected with OSD and river blindness lives in Sub-Saharan Africa or Yemen in the Middle East.

Figure 1.

The Onchocerca volvulus lifecyle. During a blood meal, an infected blackfly (genus Simulium) introduces third-stage filarial larvae onto the skin of the human host, where they penetrate into the bite wound ➊. In subcutaneous tissues the larvae ➋ develop into adult filariae, which commonly reside in nodules in subcutaneous connective tissues ➌. Adults can live in the nodules for approximately 15 years. Some nodules may contain numerous male and female worms. Females measure 33 to 50 cm in length and 270 to 400 μm in diameter, while males measure 19 to 42 mm by 130 to 210 μm. In the subcutaneous nodules, the female worms are capable of producing microfilariae for approximately 9 years. The microfilariae, measuring 220 to 360 μm by 5 to 9 μm and unsheathed, have a life span that may reach 2 years. They are occasionally found in peripheral blood, urine, and sputum but are typically found in the skin and in the lymphatics of connective tissues ➍. A blackfly ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal ➎. After ingestion, the microfilariae migrate from the blackfly’s midgut through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles ➏. There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae ➐ and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae ➑. The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the blackfly’s proboscis ➒ and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal ➊. Reproduced from the Center for Disease (https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/onchocerciasis/index.html).

Through programs of mass drug administration (MDA) with ivermectin, tremendous strides have been made in reducing the global prevalence of onchocerciasis. Transmission has been nearly eliminated in Latin America, while globally there has been a 29 percent reduction in the prevalence of onchocerciasis since 2005 [1]. However, it remains unlikely that onchocerciasis can be eliminated as a public health problem entirely through ivermectin mass treatments. The reasons for this observation have been reviewed recently, and include the inability to implement large-scale treatment programs in areas that are co-endemic for loiasis, and the potential for emerging anthelminthic drug resistance [2]. Recent genome-wide analyses revealed significant genetic variation in O. volvulus parasites, differentiating between those that are good responders to ivermectin treatment and those that are sub-optimal responders. Those parasites that responded sub-optimally were taken from individuals in Ghana and Cameroon who experienced repopulation of the skin microfilariae earlier/more extensively than expected after ivermectin treatment [3].

In addition, disease modeling studies show that transmission interruption and elimination will require routine and regular quantum reductions in O. volvulus microfilariae in the skin and subcutaneous tissues following each round of MDA, but such targets are seldom achieved [2]. The African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control predicted in 2015 that to achieve elimination 1.15 billion treatments will have needed to be administered until 2045 [4]. Such estimates indicate that onchocerciasis may not be eliminated for decades using current approaches.

To accelerate elimination and advance towards the major targets of the 2012 London Declaration for NTDs (http://unitingtocombatntds.org/sites/default/files/document/london_declaration_on_ntds.pdf), there is an effort to develop new and improved control tools. These include better diagnostics, small-molecule drugs and vaccines that can improve surveillance and achieve longer and more sustained reductions in host microfilarial loads. There is also a need for better safety profiles for interventions used in loiasis co-endemic areas of Africa. Individuals who have high blood levels of Loa loa microfilariae, a filarial infection that usually does not cause clinical disease, and receive ivermectin as part of the MDA programs to eradicate lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis, may develop a severe inflammatory reaction that can result in encephalopathy, and rarely death. In 2015, an international consortium launched a new global initiative, known as TOVA – The Onchocerciasis Vaccine for Africa [2]. TOVA is evaluating and pursuing vaccine development as a complementary control tool. Briefly, TOVA is primarily using recombinant proteins and novel adjuvant platforms, with the goal to meet at least one of the desired target product profiles (TPP). The TPP either relies on a preventive vaccine for children under the age of five who have not yet had access to MDA with ivermectin, or a therapeutic vaccine for both adults and children with onchocerciasis (Table 1) [2]. The efforts to develop an effective, safe, and logistically feasible vaccine against onchocerciasis builds on the evidence of protective immunity achieved using live attenuated vaccines. Immunization with irradiated larvae typically achieves ~70% protection in laboratory settings [5–9], but such vaccines are not feasible for mass human immunization on safety, logistical, and economic grounds. Current efforts to develop a subunit vaccine, such as confirmatory vaccine trials in large-animal models, modeling studies, and future clinical trials will build the necessary body of evidence to allow for the selection of the best TPP. The TPP presented in Table 1 was based in part on mathematical modelling that explored the potential influence of a prophylactic vaccination program on infection resurgence in areas where local elimination has been successfully achieved [10]. It assumed an initial prophylactic efficacy of 50% and an initial therapeutic efficacy of 90%, based on efficacy results in animal models. The vaccine was assumed to target 1 to 5 year olds based on the age range included in the Expanded Programme on Immunization. The modelling indicated that an onchocerciasis vaccine would have a beneficial impact in onchocerciasis-loiasis co-endemic areas, markedly reducing microfilarial load in the young (under 20 yr) age groups. The TPP for therapeutic vaccines is still hypothetical as it assumes that it will be safe to target immunologically residual microfilariae in young and adult populations living in endemic regions that went through many years of MDA with ivermectin.

Table 1.

Target product profiles for prophylactic and therapeutic onchocerciasis vaccines

| Characteristic | Desired target – prophylactica | Desired target – therapeutic (if different)b |

|---|---|---|

| Indication | A vaccine to protect against infection with infective larvae and to reduce adult worm burden and microfiladermia for the purpose of reducing morbidity and transmission | A vaccine to reduce microfiladermia for the purpose of reducing morbidity and transmission |

| Target population | Children <5 years | older children and adults that already carry adult worms |

| Route of administration | Intramuscular injection | |

| Product presentation | Single-dose vials; <0.5 ml volume of delivery | |

| Dosage schedule | Maximum of 3 immunizations given 4 weeks apart | |

| Warnings and precautions/pregnancy and lactation | Mild to moderate local injection site reactions such as erythema, oedema and pain, the character, frequency, and severity of which is similar to licensed recombinant protein vaccines. Less than 0.01% risk of urticaria and other systemic allergic reactions. Incidence of serious adverse reactions no more than licensed comparator vaccines | |

| Expected efficacy | >50% efficacy at preventing establishment of incoming worms; >90% reduction of microfilariae (based on current animal model results) | >99% reduction of microfilariae |

| Co-administration | All doses may be co-administered and/or used with other infant immunization programmes | |

| Shelf life | 4 Years | |

| Storage | Refrigeration between 2 to 8 degrees Celsius. Cannot be frozen. Can be out of refrigeration (at temperatures up to 25 degrees) for up to 72 hours | |

| Product registration | Licensure by the Food and Drug Administration and/or the European Medicine Agency | |

| Target price | Less than $10 per dose for use in low- and middle-income countries. |

adapted from [2].

the assumptions for the blank cells are similar to those expected for the prophylactic vaccine

Here, we provide a perspective of the importance of a rational design for the discovery and antigen selection process before embarking into advanced vaccine development of the onchocerciasis vaccine with a review of the current advancements and progress on the TOVA global initiative. Finally, we provide a prospective of how new technologies and artificial intelligence can catalyze and accelerate the evaluation and selection of suitable vaccine candidates leading to a greater chance of their translation into safe and efficacious human vaccines.

Discovery and evaluation of the first generation vaccine candidate antigens

Considerable effort has been expended in the 1990s on the identification of parasite molecules, primarily proteins, which induce a protective immune response in humans and in the available animal models of onchocerciasis. Anti-L3 protective immunity within the O. volvulus endemic population has been described in two populations: (1) immunity that impedes the development of a patent infection (microfilaria positive) in putatively immune (PI) individuals (i.e., individuals that had no clinical manifestations of the disease, even though they lived for at least 10 years within regions where onchocerciasis is endemic and were exposed to high transmission rates of infection); and (2) concomitant immunity, which develops in the patently infected individuals with increasing age and is independent of the immune responses that are induced by the adult worms and microfilaria associated with patent infection [11]. Protective immunity against the infective larvae was also shown in a mouse model employing O. volvulus L3 in diffusion chambers; a significant reduction of ~50% in the survival of larvae was obtained in mice immunized with normal, irradiated or freeze-thaw-killed L3 [5].

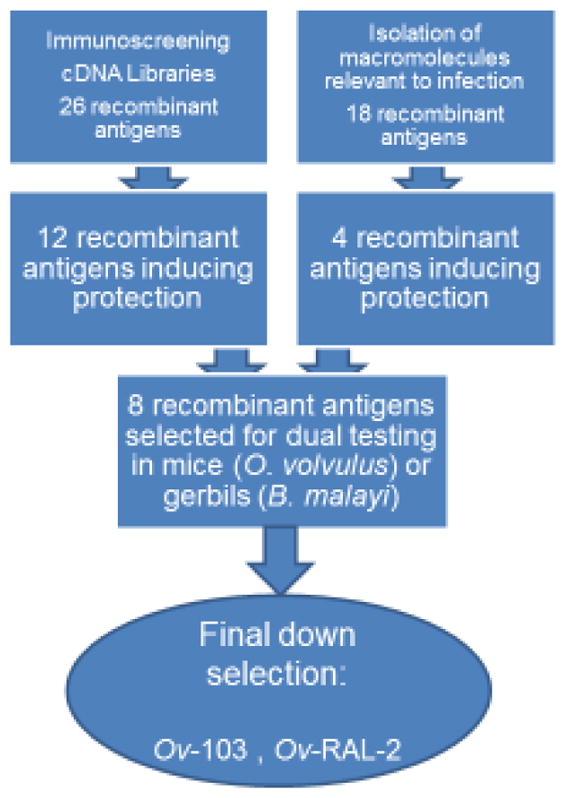

Two basic strategies were used to identify and clone O. volvulus target vaccine antigens: (1) Exploitation of the potential involvement of antibodies in protective immunity by immunoscreening various O. volvulus cDNA libraries to identify target proteins. The success of the immunoscreening effort relied mostly on the source and specificity of the immune sera from human or animal hosts and, hence, was done mostly with serum samples from individuals identified as putatively immune. In addition, sera from vaccinated or immune animals (chimpanzees, mice or cows), polyclonal antibodies raised against O. volvulus infective stage larvae also called L3, or monoclonal antibodies developed against specific parasite-antigens, were used to screen the cDNA libraries. Initially cDNA libraries constructed from adult worm stages of O. volvulus were used and later cDNA libraries constructed from O. volvulus larval stages (L3, molting L3 and fourth-stage larvae or L4) were used. Altogether, out of 26 recombinant antigens that were identified by immunoscreening and tested in the O. volvulus mouse model, 12 induced partial but significant protection (39–69%) in the presence of block copolymer, alum or Freund’s complete adjuvant [11–13]. (2) Identification and isolation of molecules thought to be essential during the infection process. These molecules would include proteins with vital metabolic functions or defense properties, which would permit the parasite to survive in immunocompetent hosts. Targeting such molecules as vaccine candidates, would block or interfere with the establishment of the parasite in the host. In addition, antigens that are not normally seen by the host, but that are nevertheless accessible to host immune-effector molecules and cells, the ‘hidden antigens’, were also thought to be potentially useful as vaccine targets [14]. The identification of the genes and isolation of the encoding proteins of interest was achieved by one or multiple of the following methods: a) screening cDNA libraries using a heterologous probes [15]; b) amplification by PCR using degenerate primers and cloning strategies [15]; c) purification of the proteins from secreted products of larval stages followed by partial amino acid sequencing and molecular cloning [16]; or d) identification of the genes of interest by searching the O. volvulus expressed sequence tag (EST) database or the EST databases generated by the Filarial Genome Project [17]. Out of 18 recombinant antigens that have been cloned using these strategies and that were tested in the O. volvulus mouse model, four (Ov-ALT-1, Ov-CHI-1, Av-ABC and Av-UBI) induced partial but significant protection. Of these, Av-ABC and Av-UBI were cloned from the rodent filarial parasite Acanthocheilonema viteae and were protective in the presence of alum or Freund’s complete adjuvant, as was Ov-ALT-1. In addition, chitinase, Ov-CHI-1, effectively induced protection using DNA immunization [18]. The Onchocerca homologue of Av-ABC has not been studied yet, whereas the Av-UBI of A. viteae is completely identical to Ov-UBI.

The characteristics of the parasite proteins corresponding to the above protective recombinant O. volvulus antigens have been described in detail previously [12, 13, 19]. Eight of the proteins, Ov-ALT-1, Ov-B8, Ov-RAL-2, Ov-B20, OI5/OI3, Ov-CHI-1, Ov-RBP-1 and Ov-103 are parasite specific antigens, whereas Ov-ASP-1 is a member of the vespid venom allergen-like protein family [20]. Six of the protective proteins are homologues to recognized proteins of higher organisms. Thus, Ov-CPI-2 (onchocystatin), Ov-TMY-1 (tropomyosin), Ov-FBA-1 (aldolase), Ov-CAL-1 (calponin), Av-ABC (ATP binding cassette protein transporter) and Av-UBI (ubiquitin) have 32, 31, 69, 42, 71 and 98% amino-acid identity, respectively, with human proteins. An important concern associated with vaccine antigens belonging to conserved gene families (e.g. enzymes, muscle proteins) is the risk of cross-reactions with host or environmental antigens. Eight antigens were also cloned from a very close relative of O. volvulus, O. ochengi, and used together to vaccinate cattle in the only field trial of a recombinant onchocerciasis vaccine performed to date [21]. These eight antigens included representatives from the parasite-specific [Oo-ALT-1, Oo-B8, Oo-RAL-2, Oo-B20 and Oo-FAR-1 (homolog of Ov-RBP-1)] as well as the highly conserved (Oo-TMY-1 Oo-FBA-1, and Oo-CPI-2) protein groups. The multivalent vaccine induced statistically significant protection also against patency (microfilaridermia), but did not significantly reduce adult worm burden [22].

Since the above described studies, only one additional antigen with protective properties, Ov-GAPDH, which was cloned using immunoscreening, has been recently reported [23]. Thus, out of a total of 16 vaccine candidates, 12 were identified by immunoscreening and 4 were identified using other approaches as illustrated in Figure 2. Below we will describe the 8 vaccine candidates chosen to be studied in greater depth for their ability to insure protection against infection.

Figure 2.

Schematics that illustrates the down-selection process that resulted in the selection of the two most promising vaccine antigens for future clinical development.

Evaluation and selection of the best vaccine candidates for a prophylactic vaccine using two small animal models

Humans are the only definitive hosts of O. volvulus. Therefore, one of the significant challenges towards the development of a vaccine against onchocerciasis has been the absence of suitable small animal models that support the life-cycle of the parasite (Figure 1). To overcome this obstacle, we adopted a dual-model screening system. In the first model, O. volvulus L3 are implanted in mice within diffusion chambers [24]. This model has the advantages of using the target human parasite and allows the unique analysis of the host molecules and cells found within the parasite microenvironment. In addition, dissection of the mechanism of immunity induced by the vaccine can be accomplished with the plethora of reagents and assays designed for murine studies. A significant disadvantage of the mouse diffusion chamber model is that the parasites will only develop for a limited time in mice and thus adult worms and microfilariae do not develop. To overcome this limitation, we tested in parallel a second system, the Brugia malayi-gerbil model of lymphatic filariasis, using homologues of promising O. volvulus antigens. Injection of L3 subcutaneously in this model allows for examination of vaccine efficacy following the natural migration of developing stages of parasites and their maturation to adult stages [25].

From the pipeline of potential candidate antigens (Figure 2), fifteen proteins were evaluated in previous studies using the mouse-Onchocerca model and identified as being able to induce partial protection following vaccination [13]. To select the most promising protective antigens for the early pre-clinical process development, a scoring system was developed that allowed ranking these 15 antigens based on their other known characteristics (reviewed in [13]), and to select eight vaccinate candidate for more extensive studies. All the 15 O. volvulus protective antigens in the O. volvulus - mouse model were given a score of 1.0 (Table 2). The added scoring was based on the following criteria: (1) score 0.2 was given to those that are nematode or parasite specific with or without known function (for example Ov-CPI-2 (cystatin), Ov-RBP-1 (retinoid binding protein) or Ov-CHI-1 (chitinase); (2) score 0.2 was given to those in which localization of the corresponding native proteins in L3 and/or molting L3 (mL3) by immunoelectron microscopy was in one or more regions that are also recognized by antibodies from protected humans and/or also from xL3 immunized and protected mice [11]; (3) score 0.2 was given to those being recognized by antibodies from protected humans (PI and INF with concomitant immunity) and/or animal models after immunization with xL3 (cattle, chimpanzees, mice); (4) score 0.2 was given to those being abundantly expressed in L3 and/or mL3, which indirectly indicates that the corresponding translated proteins are important for the parasite during the initial phases of the Ov infection; and (5) score 0.2 was given to those where studies have shown the ability of antibodies targeting the parasite antigen to kill larvae in vitro.

Table 2.

The portfolio of eight lead O. volvulus protective larval proteinsa

| Characteristics of the O. volvulus protective protein | Protection in animal models | Total Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen (kDa) | Identity (Function) | Localizationb | Immunogenicityc | #ESTsd L3/mL3 |

In vitro killing assayse | Protection in Ov mouse model (%)e [adjuvant] | Protection in lymphatic filariae models [animal model, adjuvant] | Protection in other helminth models (model, adjuvant) | |

| Ov-CPI-2 (17) | Onchocystatin, (Cysteine protease inhibitor) | Hypodermis; basal layer of cuticle; separation of L3/L4 cuticles; secretory vesicles; ES | PI sera CI sera Chimpanzee anti-Ov-xL3 |

59/9 | 96–100% inhibition of Ov L3 molting | 43–49% (alum) | Ls-cystatin; 50% reduction in patent infectionf [Ls mouse model, alum and Pam3Cys] | Ac-cystatin; 22% reduction in worm burden [Ac dog model, AS03] | 4 |

| Score | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ov-ASP-1 (25) | Novel, homologue of vespid venom allergen 5 and the PR-1 protein family | Granules of glandular esophagus; ES | PI sera CI sera Mice anti-Ov-xL3 |

50/1 | Serum from jirds immunized with Bm-ASP-1 caused 62% cytotoxicity in vitro against Bm L3 and Mf | 44 % (alum) 42% (FCA) |

Bm-ASP-1; 62% reduction in survival of L3 in chamber [jird, alum] Bm-ASP-1+Bm-ALT-2 +; 79% reduction in worm burden [jird, alum] |

Ac-ASP-2; 26% reduction in worm burden; 69% reduction in eggs output; serum from the vaccinated dogs induced in vitro 60% reduction in L3 migration [Ac dog model, AS03] | 4 |

| Score | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ov-RAL-2 (17) | Novel, nematode specific | Hypodermis | PI sera CI sera Mouse anti-Ov-xL3 |

6/4 | Anti-rAs16 from the protected pigs inhibit survival and molting of L3 in vitro | 51–60 % (FCA) | rWb-SXP/Bm14; 30% reduction of L3 survival within chambers [mice, FCA] Wb-SXP; 19% reduction of L3 survival within the chambers [mice, DNA] rBm-SXP-1; >90% reduction in microfilaremia and 35% in adult worm burden [jirds, FCA or Alum] |

rAs16; 64% reduction in A. suum L3 [mice, cholera Toxin (CT)] rAs16; 58% reduction in A. suum lung – stage L3s [pigs, CT] rAc-16; 25% reduction in hookworm worm burden, 64% reduction in egg count and significant reduction of blood loss [dogs; AS03] |

3.8 |

| Score | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ov-ALT-1 (15) | Novel, filariae specific | Granules of glandular esophagus; cuticle; channels | PI sera CI sera |

223/18 | Serum from jirds immunized with Bm-ALT-2 caused 72% cytotoxicity against Bm L3 and Mf in vitro | 39–62% (alum) |

Bm-ALT-1; 76% reduction in worm burden [jird, FCA] Bm-ALT-2; 72% reduction in survival of L3 in chamber [jird, alum] Bm-ALT-2 + Bm-ASP-1; 79% reduction in worm burden [jird, alum] |

ALT-1 is a filariae specific protein | 3 |

| Score | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ov-103 (15) | Novel, nematode specific | In L3: Basal layer of the cuticle; hypodermis; basal lamina; channels; multivesicular bodies. In Mf: surface |

PI sera CI sera |

5/0 | Anti-Ov-103 killed Mf 79% | 30–69 % (alum) | NDg | Ac-SAA-1; antibodies inhibited (46%) migration of L3 [Ac, FCA] | 3.0 |

| Score | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ov-B20 (52/65) | Novel, nematode specific | Cuticle; hypodermis; ES product | Cattle anti-Ol-xL3 | 3/2 | ND | 39 % [Alum]; | 49–60% [Av, FCA] | ND | 2.8 |

| Score | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ov-RBP-1/Ov-FBP-1 (20/22) | Novel, nematode specific; Retinoid binding protein, | Body wall; ES product | PI sera CI sera |

1/2 | ND | 42 % [BC] | 36–55% [Av, FCA] | ND | 2.8 |

| Score | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ov-CHI-1 (75) | Chitinase | Cuticle, granules of glandular esophagus | PI sera CI sera Jird anti-Av-xL3 |

0/0 | ND | 53% [DNA] | Bm-chitinase; induced 48% reduction in worm burden and >90% in Mf [jirds, FCA and alum] | ND | 2.6 |

| Score | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

This Table was adapted from [45].

Localization based on the native protein in larval stages (L3 and mL3) as determined by IEM.;

Immunogenicity based on data obtained from protected humans, putatively immune individuals (PI), infected individuals who developed concomitant immunity (CI), and/or antibodies from xL3 animal models (xL3 mouse model, cows or chimpanzees);

The number of ESTs were determined by BLAST-searching the L3 and mL3 EST datasets (3,510 and 5,165 entries, respectively) using each individual gene sequence. A gene was considered up-regulated if the ESTs occurred at least 5 times in a particular stage.

Using in vitro cytotoxicity assays few antigens were shown to be a target for antibodies raised against the recombinant antigens of Ov-CPI-2 and Ov-103. Although antibodies against the other vaccine candidates were not tested in vitro for their ability to inhibit molting or kill larvae, it appeared that immunization with the recombinant antigens Ov-CPI-2 and Ov-ALT-1 also induced significant reduction in the molting of L3. Moreover, studies using antibodies from mice immunized with the B. malayi homologous recombinant proteins of Ov-ALT-1 (Bm-ALT-2) and Ov-ASP-1 (Bm-ASP-1) have shown that anti-Bm-ALT-2 antibodies elicited 71–72% cytotoxicity in vitro against both L3 and Mf, while anti-Bm-ASP-1 antibodies induced 61–62% cytotoxicity in vitro against both L3 and Mf. Interestingly, antibodies against the homologous proteins of Ov-103 in hookworms (Ac-SAA-1) and Ov-RAL-2 in Ascaris (rAs-16), when used in vitro inhibit invasion of L3 through dog skin or caused cytotoxicity in vitro against L3, respectively.

Protection was determined in mice after two immunization with 25 μg of protein in the presence of an adjuvant or using a DNA vaccine, followed by challenge with 25 L3 within diffusion chambers, and is defined by a significant (p<0.05) % of reduction of L3 survival in the immunized mice vs. control mice.

ND=Not determined.

Abbreviations:

Ov, O. volvulus; Ol, O. lienalis; Bm, B. malayi; Wb, W. branconfti; Ls, L. sigmodontis; Av, A. viteae; Ac, A. ceylanicum; As, Ascaris Suum;; BC, block copolymer; ES, excretory–secretory product. XXX – protective in Ov and Bm; XXX- protective in Ov and other filaria animal model (Wb, Av or Lg); XXX protective in Ov and in other nematodes.

In addition, we have added two more criteria [45] that are based on more recent published and unpublished studies and thus provide added support for the selection of these 8 antigens for our proposed preclinical studies. A score of 1.0 was given to those (for examples Ov-ALT-1, Ov-CPI-2, Ov-RAL-2, chitinase, Ov-RBP-1 and Ov-B20) whose homologues have been shown to also induce protection in other filariae host–parasite systems [26–36]. Moreover, A score of 1.0 was given to those (Ov-ASP-1, Ov-103, Ov-CPI-2, Ov-RAL-2) having homologues in other nematode host–parasite systems that have been shown to be able to induce reduction in worm burden or other protective measures against hookworm infection in dogs and Ascaris in pigs [37–44]. Based on this rational innovative scoring system we have selected the top ranking 8 Ov protective antigens (Ov-CPI-2, Ov-ALT-1, Ov-RAL-2, Ov-ASP-1, Ov-103, Ov-RBP-1, Ov-CHI-1 and Ov-B20) for which we propose to conduct extensive preclinical evaluation and further selection. Those selected are ranked between a total score of 4.0 to 2.6 (Table 2). Those of the original 15 rOvAgs that were not selected were only ranked at a total score of 1.0 to 1.6.

The eight selected O. volvulus proteins and the B. malayi homologues were expressed in both bacterial (Escherichia coli) and eukaryotic (Pichia) expression systems. In the presence of the adjuvant alum, the recombinant Ov-103 and Ov-RAL-2 proteins, together with their Bm-103 and Bm-RAL-2 homologues emerged as the most promising candidates in each animal model, validating the robustness of our selection and prioritization process. Combination of these two antigens by either co-administration vaccine strategies or single injections using a recombinant fusion protein vaccine induced enhanced levels of protective immunity, demonstrating that the antigens could act synergistically in both systems [45, 46]. Furthermore, these co-administered molecules or the fusion proteins reduced embryogenesis in B. malayi females, suggesting a potential impact also on microfilaremia and transmission [46].

Various adjuvants were evaluated and compared for their ability to improve efficacy by enhancing the killing of O. volvulus in diffusion chambers implanted in mice. Only adjuvants that induced Th2 responses, as determined by cytokine profiles, were effective at enhancing the vaccine efficacy, consistent with reports showing that IL-4, IL-5, and functional eosinophils are necessary for the development of adaptive immunity in mice immunized with irradiated O. volvulus larvae [47–49], and the Litomosoides sigmodontis murine model [50–54]. Co-administration of both of the O. volvulus antigens enhanced parasite killing as compared to single antigen immunizations, with all of the adjuvants inducing Th2 responses. Antigen specific IgG1 was the dominant antibody isotype that developed in protected immunized mice. Based on chemokine levels within the diffusion chambers, it appears that eosinophils, macrophages and neutrophils participate in the killing mechanism. These findings suggest that the mechanism of protective immunity induced by the two O. volvulus antigens is multifactorial with roles for cytokines, chemokines, antibody and specific effector cells [55]. This observation was confirmed in the B. malayi–gerbil model, where it was demonstrated that serum from gerbils immunized with the two B. malayi antigens on alum, killed the parasites in vitro, in collaboration with peritoneal exudate cells [46].

Thus, based on the two model systems, O. volvulus in mice and B. malayi in gerbils, an effective two-antigen vaccine against O. volvulus has been identified. It consists of the proteins Ov-103 and Ov-RAL-2, administered with an adjuvant that induces Th2 responses. Immunization with both antigens enhanced the protective immune response and the mechanism of protective immunity appears to be antibody and effector cell dependent, in both model systems.

As mentioned above, a third small-animal model, the L. sigmodontis-BALB/c mouse model, has been developed and used for studying anti-filarial immunity and vaccines [56, 57]. This model also allows full development of the infective larvae to adult worms producing circulating microfilariae. It will be worthwhile to incorporate this third model into future efficacy pipeline studies and validate the L. sigmodontis homologous of the O. volvulus vaccine candidates also in this filarial infection model in mice.

The need for a rational and efficient process to generate a robust pipeline of second generation vaccine candidate antigens

The disappointing results obtained many times during human proof of concept clinical trials, continue to highlight the challenges and limitations of how to best predict whether a vaccine candidate translates successfully from animal testing into humans [58, 59].

Many articles call for a change in paradigm from an empirical development strategy to a rational vaccine design [60–62]. Amongst the parameters driving decisions during the development of new vaccine targets, the current consensus is that antigen selection and optimization represents the foundation in vaccine design. In addition, it is essential to have available appropriate preclinical models, but it is also crucial to have optimal vaccine formulations, adjuvants and delivery strategies. These are essential elements to target the appropriate immune mechanisms of protection [63]. This is especially important when developing vaccines for infectious diseases, such as for onchocerciasis, because unfortunately scientific advances and tools are still trailing and there is also a need for safety and efficacy studies to be done more quickly, with more certainty and at lower costs.

For example, strategies to identify the ideal Onchocerca vaccine candidate antigens can rely on selection processes based on the knowledge of candidates inducing effective immune responses, identifying antibody-based epitopes via computational prediction tools, down-selection of candidates based on predictions of sequences that could induce immunopathology or allergy, and continuous assessment of parasite molecules by structural biology and stability assessments. Hence, systems biology approaches continue to lead the efforts seeking better understanding of the mechanisms of protection and safety of vaccines [61].

Considerable efforts have also been done in the area of novel adjuvant development. Subunit vaccines need help with secondary molecules modulating the immune responses. TOVA Initiative is also incorporating into the development path the evaluation of other adjuvants besides the traditional phosphate or hydroxide salts of aluminum such as oil-in-water emulsions and synthetic toll-like receptor agonists [62]. The objective is to select adjuvants that facilitate the most effective response, while in parallel investigate their optimized use, route and molecular mechanism.

Selecting and evaluating the ideal delivery route and system also provides a benefit towards rational vaccine design. Investigating the mechanisms to overcome pre-existing immunity, an understanding of the basis for the stimulation of memory responses, and examining the interface between innate and adaptive immunity can also maximize the potential for vaccines to trigger long-lasting immunity and protection.

Using ‘omics to catalyze and accelerate the decision process for the discovery of second generation vaccine candidate antigens

Recent technology advancements of the 21st Century have allowed the use of new animal or computer-based predictive models, biomarkers for safety and efficacy, and clinical evaluation techniques to assist in the improvement of predictability and efficacy needed along the critical path to move discoveries from the laboratory bench to licensure. Ultimately, developing and identifying methods to establish correlate markers or surrogate endpoints for protection will be necessary and essential [60].

The current accumulation of molecular data and expansion of filarial parasite RNA and DNA databases, as well as proteomic datasets, has already provided a fresh start by permitting a more rational approach to vaccine candidate discovery [64]. For instance, the availability of genomes for B. malayi, L. sigmodontis and O. ochengi has facilitated numerous secretome studies across the parasite lifecycle [65–67]. One group of vaccine candidates that was identified by this unbiased, high-throughput approach was a ShK toxin domain family in which each individual member contains six ShK domains; a situation that is unique to filarial nematodes [30]. These abundant secreted proteins probably have an immunomodulatory role [66, 68] that could be targeted using antigens incorporating rational mutation of critical amino acid residue(s); an approach that has been used successfully with CPI-2 [56, 69]. In addition, the O. volvulus genome, as well as the transcriptome and proteome of each stage from the definitive host (L3, molting L3, L4, adult male, adult female, and nodule and skin microfilaria stages), has been published recently [70, 71]. These new datasets, when combined with immunomics [72–76], have provided an opportunity to identify the antigens that, either alone or in combination, function as targets of natural acquired immunity against filariae. Recombinant protein or synthetic peptide arrays can be used to interrogate the genome-wide proteome of infectious pathogens consisting of the entire potential antigens using only small amounts of individual sera samples. This approach permits investigators to perform extensive longitudinal, epidemiological and surveillance analyses, as well as identifying immune responses at various stages of infections in the human host in a fashion not possible with other technologies [77, 78].

Using the immunomics approach with sera samples from putatively immune individuals from Cameroon and the Americas versus sera from infected individuals, six new potential vaccine antigens were identified. This was accomplished by screening for IgG1, IgG3 and IgE antibody responses against a protein array containing 362 O. volvulus recombinant proteins [71], and identifying those with a significant IgG1 and/or IgG3 reactivity with little-to-no IgE reactivity. Notably, four of these antigens (OVOC10819, OVOC5395, OVOC11598 and OVOC12235) are highly expressed during the development of the early stages of the infective stage larvae, L3, in the human host; these would be worthy candidates for testing their efficacy in a preventative vaccine model of infection. Interestingly, the two other proteins (OVOC8619 and OVOC7083) are highly expressed by the microfilariae and were mostly recognized by sera from the putatively immune individuals who never developed a patent infection with microfilaridermia; these would be worthy to be tested as vaccine candidates for a therapeutic vaccine [71].

The initial objective for the Onchocerca vaccine was to identify candidate antigens for a prophylactic vaccine to be administered to children under the age of five who have not yet had access to MDA with ivermectin (Table 1); the first generation of our vaccine candidates fulfilled this objective. However, the immunomics approach now opens new possibilities for also developing a safe anti-transmission or therapeutic vaccine. The immunomics studies reported by Bennuru et al. [71] were the first time in which the O. volvulus stage-specific genome-wide expression data was used to discover empirically novel vaccine candidates. It would be of great interest to test the novel vaccine candidates identified by the immunomics approach [71] in the O. volvulus diffusion chamber mouse model [45] and B. malayi – gerbil infection model to validate whether the immunomics approach actually have identified vaccine candidates that protect against L3 and/or microfilariae.

Other potential applications of immunomic approaches include unbiased characterization of the immune response at the site of infection. In the O. ochengi system in cattle, a recent secretome analysis of nodule fluid identified almost 500 host proteins that ‘bathe’ the adult worms in vivo [67]. Interestingly, these proteins were dominated by antimicrobial proteins, such as cathelicidins, which probably originate from the neutrophils that dominate the intranodular environment. A parallel approach could be used to explore the immunological changes that occur within nodules in animals displaying partial protection induced by vaccination. Such studies will be very valuable in the future for the machine learning approach described below.

Prospective: The potential for machine learning to accelerate the evaluation and selection of vaccine candidates

Decades of research on prototype anti-filarial vaccines in animal models, the application of transgenic knockout mouse strains, and immunological studies of onchocerciasis patients presenting different clinical phenotypes, has led to a broad consensus on the characteristics of protective immunity and some of the key factors that drive immunopathology. Thus, a Th2-biased immune response directed against incoming infective larvae, with a secondary (but important) role for a Th1 component and the modulating influence of T-regulatory cells, is associated with ‘benign’ protection [57, 79, 80]. Conversely, at least in humans, unregulated Th2 responses against microfilariae in conjunction with Th17-driven inflammation and profound eosinophilia lead to effective parasite killing, but at the price of a hyperreactive form of onchocerciasis exhibiting severe skin inflammation also called sowda if the inflammation is unilaterally predominant [81, 82]. This very rare condition is associated with certain genetic polymorphisms in immune-related genes [83, 84]. However, adverse reactions with a clear immunological component are possible in a wider range of patients, as is not uncommon with antifilarial chemotherapy [85, 86]. Consequently, accurately predicting whether a vaccine candidate is likely to be both safe and effective is very challenging using conventional approaches alone, especially as we lack animal models that recapitulate the pathology seen in human onchocerciasis.

Traditional statistical approaches can be powerful at disentangling these immunological events, but tend not to generalize well from model systems to humans. However, machine learning techniques have been developed to improve generalizability by tuning models to maximize prediction accuracy to independent test samples, and tend to deal with large numbers of variables better than traditional statistical approaches [87, 88]. Such methods have been used successfully to analyze immune responses to bacterial infection using whole blood transcriptional signatures [89], and to detect local pathogen-specific immune profiles in peritoneal dialysis patients [87]. In principle, by combining vaccinology read-outs from animal models and natural immunity in humans, it may therefore be possible to improve the selection of vaccine candidates earlier than currently possible. Thus, by identifying robust markers of immunity that generalize well, such approaches may help bridge the divide between development, preclinical, and clinical phases of vaccine development (Figure 3).

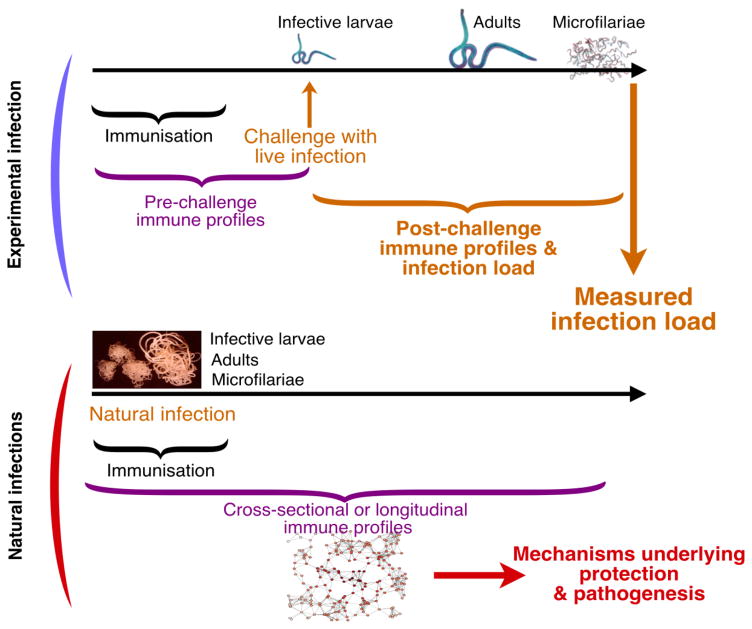

Figure 3.

Combining a systems analysis of response to vaccines and machine learning algorithms to help predict vaccine efficacy. (A) Applying machine learning to experimental infections across multiple model systems and species can help identify which immune variables throughout the time course of an infection most reliably predict infection load, while ensuring the trained models generalize well across biological systems. (B) These optimized models may then be useful in predicting vaccine efficacy in human trials in two ways: identifying what data to collect and predicting likely vaccine efficacy using incomplete data that are typical of human field studies.

Concluding remarks

Although it was previously considered that O. volvulus infections can be controlled using only MDA with ivermectin, it is becoming increasingly clear that without additional modalities such as drugs which kill or permanently sterilize the adult worms and/or a vaccine, elimination of onchocerciasis from Sub Saharan Africa may remain an unfulfilled goal. Vaccines aimed at preventing infection (anti-L3), and/or reduce microfilariae in adults and children with onchocerciasis could be the essential complement for the successful control or elimination of both diseases.

The successful vaccines developed against taeniases and the major advances already made in development of human anthelminthic vaccines [90], show that it is indeed possible to develop and test protective vaccines against multicellular parasites. In regard to O. volvulus, the human studies have suggested that protective immunity can develop in humans. The experimental and natural infections of calves have demonstrated that protective immunity does develop and that vaccines can protect animals from infection under natural conditions. Moreover, using the small animal models for antigen screening have already accomplished the identification of two lead vaccine candidates; now the challenge is to optimize and formulate these vaccines for human usage, which can take advantage of the procedures currently being developed for the human hookworm and schistosome vaccines [91, 92], making the process potently quicker than usually expected (see Outstanding Questions). Efforts to develop novel diagnostic assays that support the monitoring of current and future control measures are underway and are expected to soon provide diagnostic assays that can predict efficacy of the prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines in human clinical trials.

Outstanding Questions.

What additional tools are needed to support the elimination of onchocerciasis in Africa?

Adjuvants are an important component for vaccine delivery; additional adjuvants that may increase efficacy. Should other adjuvants be tested versus the alum formulated vaccines?

Should we optimize the O. volvulus vaccine in regard to dosage, number of immunization and ability to provide sufficient memory?

Should we proceed to identify new vaccine candidates for prophylactic and/or therapeutic vaccines using more rational approaches?

How can new technologies and artificial intelligence catalyze and accelerate the evaluation and selection of more effective vaccine candidates leading to a greater chance of their translation into safe and efficacious human vaccines?

Can we develop diagnostic assays that can predict efficacy of the prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines in human clinical trials?

The task ahead is to assure continued pre-clinical development by convincing potential donors that O. volvulus vaccine production and testing is a realistic goal worth supporting. The potential development of drug resistance to the drugs used for MDA and the many years of MDA now being anticipated to control onchocerciasis might provide such impetus.

Box 1. Key points that support the advancement and progress towards an onchocerciasis vaccine.

It remains unlikely that onchocerciasis can be eliminated entirely through ivermectin mass treatments

An international consortium launched in 2015 a new global initiative, known as TOVA – The Onchocerciasis Vaccine for Africa – with the goal of evaluating and pursuing vaccine development as a complementary control tool

A rational design for the antigen discovery and selection process before embarking into advanced vaccine development of the onchocerciasis vaccine resulted in the identification of two recombinant proteins – Ov-103 and Ov-RAL-2 – that individually or in combination induced significant protection against infection

Acknowledgments

This work described in this review was support in part by NIH/NIAID grant 1R01AI078314 and by the European Commission grant HEALTH-F3-2010-242131. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Disease GBD, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotez PJ, et al. The Onchocerciasis Vaccine for Africa--TOVA--Initiative. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(1):e0003422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle SR, et al. Genome-wide analysis of ivermectin response by Onchocerca volvulus reveals that genetic drift and soft selective sweeps contribute to loss of drug sensitivity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(7):e0005816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YE, et al. Control, elimination, and eradication of river blindness: scenarios, timelines, and ivermectin treatment needs in Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(4):e0003664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange AM, et al. Induction of protective immunity against larval Onchocerca volvulus in a mouse model. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49(6):783–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babayan SA, et al. Vaccination against filarial nematodes with irradiated larvae provides long-term protection against the third larval stage but not against subsequent life cycle stages. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(8):903–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tchakoute VL, et al. In a bovine model of onchocerciasis, protective immunity exists naturally, is absent in drug-cured hosts, and is induced by vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(15):5971–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601385103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Achukwi MD, et al. Successful vaccination against Onchocerca ochengi infestation in cattle using live Onchocerca volvulus infective larvae. Parasite Immunol. 2007;29(3):113–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Goff L, et al. Parasitology and immunology of mice vaccinated with irradiated Litomosoides sigmodontis larvae. Parasitology. 2000;120(Pt 3):271–80. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099005533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner HC, et al. Human Onchocerciasis: Modelling the Potential Long-term Consequences of a Vaccination Programme. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(7):e0003938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lustigman S, et al. CD4+ dependent immunity to Onchocerca volvulus third-stage larvae in humans and the mouse vaccination model: common ground and distinctions. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33(11):1161–71. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham D, et al. Development of a recombinant antigen vaccine against infection with the filarial worm Onchocerca volvulus. Infect Immun. 2001;69(1):262–70. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.262-270.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lustigman S, et al. Towards a recombinant antigen vaccine against Onchocerca volvulus. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18(3):135–41. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(01)02211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sher A. Vaccination against parasites: special problems imposed by the adaptation of parasitic organisms to the host immune response. In: Englund PT, Sher A, editors. The Biology of Parasitism. Alan R. Liss, INC; 1988. pp. 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henkle-Duhrsen K, Kampkotter A. Antioxidant enzyme families in parasitic nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;114(2):129–42. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Y, et al. Chitinase genes expressed by infective larvae of the filarial nematodes, Acanthocheilonema viteae and Onchocerca volvulus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;75(2):207–19. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lizotte-Waniewski M, et al. Identification of potential vaccine and drug target candidates by expressed sequence tag analysis and immunoscreening of Onchocerca volvulus larval cDNA libraries. Infect Immun. 2000;68(6):3491–501. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3491-3501.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison RA, et al. DNA immunisation with Onchocerca volvulus chitinase induces partial protection against challenge infection with L3 larvae in mice. Vaccine. 1999;18(7–8):647–55. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lustigman S, Abraham D. Onchocerciasis. In: Barrett ADT, Stanberry LR, editors. Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Chapter 67. Academic Press Inc - Elsevier Science & Technology; 2008. pp. 1379–1400. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tawe W, et al. Angiogenic activity of Onchocerca volvulus recombinant proteins similar to vespid venom antigen 5. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;109(2):91–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makepeace BL, Tanya VN. 25 Years of the Onchocerca ochengi Model. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32(12):966–978. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makepeace BL, et al. Immunisation with a multivalent, subunit vaccine reduces patent infection in a natural bovine model of onchocerciasis during intense field exposure. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(11):e544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erttmann KD, et al. Cloning, characterization and DNA immunization of an Onchocerca volvulus glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Ov-GAPDH) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1741(1–2):85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abraham D, et al. Survival and development of larval Onchocerca volvulus in diffusion chambers implanted in primate and rodent hosts. J Parasitol. 1993;79(4):571–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris CP, et al. A comprehensive, model-based review of vaccine and repeat infection trials for filariasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(3):381–421. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frank GR, et al. Molecular cloning of a developmentally regulated protein isolated from excretory-secretory products of larval Dirofilaria immitis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;75(2):231–40. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregory WF, et al. The abundant larval transcript-1 and -2 genes of Brugia malayi encode stage-specific candidate vaccine antigens for filariasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68(7):4174–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4174-4179.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anand SB, et al. Comparison of Immuno prophylactic efficacy of Bm rALT2 or Bm rVAH or rALT + rVAH by Single and Multiple antigen vaccination mode. American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;75(5):295. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaff AW, et al. Litomosoides sigmodontis cystatin acts as an immunomodulator during experimental filariasis. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32(2):171–8. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lustigman S, et al. Characterization of an Onchocerca volvulus cDNA clone encoding a genus specific antigen present in infective larvae and adult worms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;45(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lustigman S, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of onchocystatin, a cysteine proteinase inhibitor of Onchocerca volvulus. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(24):17339–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramachandran S, et al. The larval specific lymphatic filarial ALT-2: induction of protection using protein or DNA vaccination. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48(12):945–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang SH, et al. Evaluation of recombinant chitinase and SXP1 antigens as antimicrofilarial vaccines. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56(4):474–81. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adam R, et al. Identification of chitinase as the immunodominant filarial antigen recognized by sera of vaccinated rodents. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(3):1441–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor MJ, et al. Onchocerca volvulus larval antigen, OvB20, induces partial protection in a rodent model of onchocerciasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63(11):4417–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4417-4422.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jenkins RE, et al. Characterization of a secreted antigen of Onchocerca volvulus with host-protective potential. Parasite Immunol. 1996;18(1):29–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1996.d01-10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghosh K, et al. Vaccination with alum-precipitated recombinant Ancylostoma-secreted protein 1 protects mice against challenge infections with infective hookworm (Ancylostoma caninum) larvae. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(6):1380–3. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goud GN, et al. Expression of the Necator americanus hookworm larval antigen Na-ASP-2 in Pichia pastoris and purification of the recombinant protein for use in human clinical trials. Vaccine. 2005;23(39):4754–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hotez PJ, et al. New technologies for the control of human hookworm infection. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22(7):327–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bethony JM, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of the Na-ASP-2 Hookworm Vaccine in unexposed adults. Vaccine. 2008;26(19):2408–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhan B, et al. Ac-SAA-1, an immunodominant 16 kDa surface-associated antigen of infective larvae and adults of Ancylostoma caninum. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34(9):1037–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuji N, et al. Intranasal immunization with recombinant Ascaris suum 14-kilodalton antigen coupled with cholera toxin B subunit induces protective immunity to A. suum infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69(12):7285–92. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7285-7292.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuji N, et al. Mice intranasally immunized with a recombinant 16-kilodalton antigen from roundworm Ascaris parasites are protected against larval migration of Ascaris suum. Infect Immun. 2003;71(9):5314–23. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5314-5323.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuji N, et al. Recombinant Ascaris 16-Kilodalton protein-induced protection against Ascaris suum larval migration after intranasal vaccination in pigs. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(10):1812–20. doi: 10.1086/425074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hess JA, et al. Vaccines to combat river blindness: expression, selection and formulation of vaccines against infection with Onchocerca volvulus in a mouse model. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44(9):637–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arumugam S, et al. Vaccination of Gerbils with Bm-103 and Bm-RAL-2 Concurrently or as a Fusion Protein Confers Consistent and Improved Protection against Brugia malayi Infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(4):e0004586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson EH, et al. Immune responses to third stage larvae of Onchocerca volvulus in interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 knockout mice. Parasite Immunol. 1998;20(7):319–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1998.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lange AM, et al. IL-4- and IL-5-dependent protective immunity to Onchocerca volvulus infective larvae in BALB/cBYJ mice. J Immunol. 1994;153(1):205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abraham D, et al. Immunoglobulin E and eosinophil-dependent protective immunity to larval Onchocerca volvulus in mice immunized with irradiated larvae. Infect Immun. 2004;72(2):810–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.810-817.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volkmann L, et al. Interleukin-4 is essential for the control of microfilariae in murine infection with the filaria Litomosoides sigmodontis. Infect Immun. 2001;69(5):2950–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2950-2956.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin C, et al. IL-5 is essential for vaccine-induced protection and for resolution of primary infection in murine filariasis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2000;189(2):67–74. doi: 10.1007/pl00008258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Specht S, et al. Lack of eosinophil peroxidase or major basic protein impairs defense against murine filarial infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74(9):5236–43. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00329-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saeftel M, et al. Synergism of gamma interferon and interleukin-5 in the control of murine filariasis. Infect Immun. 2003;71(12):6978–85. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.6978-6985.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hubner MP, et al. Type 2 immune-inducing helminth vaccination maintains protective efficacy in the setting of repeated parasite exposures. Vaccine. 2010;28(7):1746–57. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hess JA, et al. The Immunomodulatory Role of Adjuvants in Vaccines Formulated with the Recombinant Antigens Ov-103 and Ov-RAL-2 against Onchocerca volvulus in Mice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(7):e0004797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Babayan SA, et al. Deletion of parasite immune modulatory sequences combined with immune activating signals enhances vaccine mediated protection against filarial nematodes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(12):e1968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Allen JE, et al. Of mice, cattle, and humans: the immunology and treatment of river blindness. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(4):e217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pedrique B, et al. The drug and vaccine landscape for neglected diseases (2000–11): a systematic assessment. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e371–9. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pronker ES, et al. Risk in vaccine research and development quantified. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nabel GJ. Designing tomorrow’s vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):551–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Gregorio E, Rappuoli R. From empiricism to rational design: a personal perspective of the evolution of vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(7):505–14. doi: 10.1038/nri3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rueckert C, Guzman CA. Vaccines: from empirical development to rational design. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(11):e1003001. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griffin JF. A strategic approach to vaccine development: animal models, monitoring vaccine efficacy, formulation and delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(6):851–61. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lustigman S, et al. The role of ‘omics’ in the quest to eliminate human filariasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(4):e0005464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bennuru S, et al. Brugia malayi excreted/secreted proteins at the host/parasite interface: stage- and gender-specific proteomic profiling. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(4):e410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Armstrong SD, et al. Comparative Analysis of the Secretome from a Model Filarial Nematode (Litomosoides sigmodontis) reveals Maximal Diversity in Gravid Female Parasites. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(10):2527–2544. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.038539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Armstrong SD, et al. Stage-specific Proteomes from Onchocerca ochengi, Sister Species of the Human River Blindness Parasite, Uncover Adaptations to a Nodular Lifestyle. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15(8):2554–75. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.055640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chhabra S, et al. Kv1.3 channel-blocking immunomodulatory peptides from parasitic worms: implications for autoimmune diseases. FASEB J. 2014;28(9):3952–64. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-251967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arumugam S, et al. Vaccination with a genetically modified Brugia malayi cysteine protease inhibitor-2 reduces adult parasite numbers and affects the fertility of female worms following a subcutaneous challenge of Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) with B. malayi infective larvae. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44(10):675–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cotton JA, et al. The genome of Onchocerca volvulus, agent of river blindness. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16216. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bennuru S, et al. Stage-Specific Transcriptome and Proteome Analyses of the Filarial Parasite Onchocerca volvulus and Its Wolbachia Endosymbiont. MBio. 2016;7(6) doi: 10.1128/mBio.02028-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Assis RR, et al. A next-generation proteome array for Schistosoma mansoni. Int J Parasitol. 2016;46(7):411–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Driguez P, et al. Schistosomiasis vaccine discovery using immunomics. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doolan DL, et al. Profiling humoral immune responses to P. falciparum infection with protein microarrays. Proteomics. 2008;8(22):4680–94. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gaze S, et al. An immunomics approach to schistosome antigen discovery: antibody signatures of naturally resistant and chronically infected individuals from endemic areas. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(3):e1004033. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tang YT, et al. Genome of the human hookworm Necator americanus. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):261–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bacarese-Hamilton T, et al. Protein microarrays: from serodiagnosis to whole proteome scale analysis of the immune response against pathogenic microorganisms. Biotechniques Suppl. 2002:24–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lagatie O, et al. Identification of three immunodominant motifs with atypical isotype profile scattered over the Onchocerca volvulus proteome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(1):e0005330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoerauf A, Brattig N. Resistance and susceptibility in human onchocerciasis--beyond Th1 vs. Th2. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(01)02173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Babayan SA, et al. Future prospects and challenges of vaccines against filariasis. Parasite Immunol. 2012;34(5):243–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Katawa G, et al. Hyperreactive onchocerciasis is characterized by a combination of Th17-Th2 immune responses and reduced regulatory T cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(1):e3414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brattig NW. Pathogenesis and host responses in human onchocerciasis: impact of Onchocerca filariae and Wolbachia endobacteria. Microbes Infect. 2004;6(1):113–28. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meyer CG, et al. HLA-D alleles associated with generalized disease, localized disease, and putative immunity in Onchocerca volvulus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(16):7515–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hoerauf A, et al. The variant Arg110Gln of human IL-13 is associated with an immunologically hyper-reactive form of onchocerciasis (sowda) Microbes Infect. 2002;4(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Keiser PB, et al. Bacterial endosymbionts of Onchocerca volvulus in the pathogenesis of posttreatment reactions. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(6):805–11. doi: 10.1086/339344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wildenburg G, et al. Lymph nodes of onchocerciasis patients after treatment with ivermectin: reaction of eosinophil granulocytes and their cationic granule proteins. Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45(2):87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang J, et al. Machine-learning algorithms define pathogen-specific local immune fingerprints in peritoneal dialysis patients with bacterial infections. Kidney Int. 2017;92(1):179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hastie T, et al. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction. 10. Springer; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Urrutia A, et al. Standardized Whole-Blood Transcriptional Profiling Enables the Deconvolution of Complex Induced Immune Responses. Cell Rep. 2016;16(10):2777–91. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hotez PJ, et al. Human anthelminthic vaccines: Rationale and challenges. Vaccine. 2016;34(30):3549–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Diemert DJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the Na-GST-1 hookworm vaccine in Brazilian and American adults. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(5):e0005574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Merrifield M, et al. Advancing a vaccine to prevent human schistosomiasis. Vaccine. 2016;34(26):2988–91. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.MacDonald AJ, et al. Ov-ASP-1, the Onchocerca volvulus homologue of the activation associated secreted protein family is immunostimulatory and can induce protective anti-larval immunity. Parasite Immunol. 2004;26(1):53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-9838.2004.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goud GN, et al. Cloning, yeast expression, isolation, and vaccine testing of recombinant Ancylostoma-secreted protein (ASP)-1 and ASP-2 from Ancylostoma ceylanicum. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(5):919–29. doi: 10.1086/381901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.MacDonald AJ, et al. Differential Cytokine and Antibody Responses to Adult and Larval Stages of Onchocerca volvulus Consistent with the Development of Concomitant Immunity. Infect Immun. 2002;70(6):2796–804. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2796-2804.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lustigman S, et al. Identification and characterization of an Onchocerca volvulus cDNA clone encoding a microfilarial surface-associated antigen. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50(1):79–93. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90246-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Abdel-Wahab N, et al. OvB20, an Onchocerca volvulus-cloned antigen selected by differential immunoscreening with vaccination serum in a cattle model of onchocerciasis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;76(1–2):187–99. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02558-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mpagi JL, et al. Humoral responses to a secretory Onchocerca volvulus protein: differences in the pattern of antibody isotypes to recombinant Ov20/OvS1 in generalized and hyperreactive onchocerciasis. Parasite Immunol. 2000;22(9):455–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2000.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wu Y, et al. Human immune responses to infective stage larval-specific chitinase of filarial parasite, Onchocerca volvulus, Ov-CHI-1. Filaria J. 2003;2(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]