Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Methylation of specific microRNAs (miRNAs) often occurs in an age-dependent manner, as a field defect in some instances, and may be an early event in colitis-associated carcinogenesis. We aimed to determine whether specific mRNA signature patterns (MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, MIR34B/C) could be used to identify patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) who are at increased risk for colorectal neoplasia.

METHODS

We obtained 387 colorectal tissue specimens collected from 238 patients with UC (152 without neoplasia, 17 with dysplasia, and 69 with UC-associated colorectal cancer [UC-CRC]), from 2 independent cohorts in Japan between 2005 and 2015. We quantified methylation of miRNAs by bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis. We analyzed clinical data to determine whether miRNA methylation patterns were associated with age, location, or segment of the colorectum (cecum, transverse colon, and rectum). Differences in tissue miRNA methylation and expression levels were compared among samples and associated with cancer risk using the Wilcoxon, Mann-Whitney, and Kruskal–Wallis tests as appropriate. We performed a validation study of samples from 90 patients without UC and 61 patients with UC-associated dysplasia or cancer to confirm the association between specific methylation patterns of miRNAs in non-tumor rectal mucosa from patients with UC at risk of UC-CRC.

RESULTS

Among patients with UC without neoplasia, rectal tissues had significantly higher levels of methylation levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, and MIR137 than in proximal mucosa; levels of methylation were associated with age and duration of UC in rectal mucosa. Methylation of all miRNAs was significantly higher in samples from patients with dysplasia or CRC compared with samples from patients without neoplasia. Receiver operating characteristic analysis revealed that methylation levels of miRNAs in rectal mucosa accurately differentiated patients with CRC from those without. Methylation of MIR137 in rectal mucosa was an independent risk factor for UC-CRC. Methylation patterns of a set of miRNAs (panel) could discriminate discriminate UC patients with or without dysplasia or CRC in the evaluation cohort (area under the curve, 0.81) and the validation cohort (area under the curve, 0.78).

CONCLUSIONS

In evaluation and validation cohorts, we found specific miRNAs to be methylated in rectal mucosal samples from patients with UC with dysplasia or CRC compared with patients without neoplasms. This pattern also associated with patient age and might be used to identify patients with UC at greatest risk for developing UC-CRC. Our findings provide evidence for a field defect in rectal mucosa from patients with UC-CRC.

Keywords: MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, MIR34B/C, Methylation, Ulcerative Colitis, Colitis-Associated Cancer

Patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) who are at higher risk for developing colorectal cancer (CRC) are recommended to undergo periodic colonoscopic surveillance with multiple biopsies for earlier diagnosis and treatment of UC-associated CRC (UC-CRC).1,2 However, it remains unclear whether current colonoscopic surveillance approaches are effective for the early detection of UC-CRC. The detection of such lesions endoscopically is challenging, and histologically it can be an arduous task to differentiate these dysplastic or neoplastic foci from inflamed or regenerating epithelium.3 Consequently, to improve surveillance strategies, there is an unmet need for biomarkers that can help identify patients who are at high risk for UC-CRC.

In most human cancers, aberrant hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands and subsequent inactivation of key tumor suppressor genes is a frequent step in tumorigenesis. In CRC, this epigenetic alteration has been shown to associate with an age-related pattern (type A) and a cancer-specific methylation pattern (type C).4 Age-related methylation has been suggested to be an important contributor to the acquired predisposition to CRC, and the 2 types may overlap in a chronic inflammation-associated disease such as UC.5

Inflammation in UC patients characteristically begins in the rectal mucosa and spreads progressively and contiguously to the proximal colon.6 In UC-associated carcinogenesis, chronic inflammation has been proposed to increase epithelial cell turnover in the colonic mucosa, resulting in accelerated aging of colonic mucosa and enhanced vulnerability for acquiring genetic and epigenetic alternations.7–11 These results suggest that an age-related methylation field defect could potentially be exploited for the identification of UC patients who are at increased risk for developing UC-CRC later in life. Therefore, we proposed a systematic exploration of the methylation status of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C in UC patients. The biological functions of these miRNAs have been characterized as tumor suppressors, and hypermethylation of CpG islands in all of these miRNAs has been demonstrated in CRC associated with or without UC.12–16 Moreover, their methylation pattern has been shown to associate with increasing age, and a field defect has been observed in the uninvolved colonic mucosa of CRC patients.15–24

Herein, we hypothesized that hypermethylation of specific miRNAs in normal aging colorectal epithelium may be an early event in colitis-associated CRC, leading us to undertake a systematic and comprehensive study (Supplementary Figure 1). First, we determined whether a panel of miRNAs exhibited an age- and location-dependent methylation pattern in multiple mucosal tissues collected from different segments of the colorectum (cecum, transverse colon, and rectum) in a large cohort of UC patients without colorectal neoplasia (dysplasia or cancer). Next we investigated whether methylation patterns of these miRNAs occurred in a cancer-dependent manner by analyzing both non-neoplastic and neoplastic mucosa from UC patients with and without colorectal neoplasia. By examining the methylation status of these miRNAs specifically in the non-neoplastic rectal mucosa of UC patients with and without neoplasia elsewhere in the colon, we looked for a field defect in the rectal biopsies from UC patients. The underlying hypothesis was to evaluate whether aberrant methylation of these miRNAs in non-neoplastic rectal mucosa could identify patients at greatest risk for UC-CRC.

Methods

Patients and Samples

A total of 387 colorectal epithelial specimens, including 362 non-neoplastic and 25 neoplastic tissues that were obtained from 238 patients diagnosed with UC from 2 different patient cohorts enrolled at Mie University and Hyogo College of Medicine in Japan (Supplementary Figure 1) were analyzed in this study (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The study design included a 3-step analysis for the clinical evaluation phase to determine whether these miRNAs exhibited age-, location-, or tissue-dependent methylation patterns in multiple mucosal tissues collected from different segments of the colorectum (cecum, transverse colon, and rectum) in a large cohort of UC patients with or without dysplasia or cancer. The subsequent external validation phase confirmed our observation that aberrant methylation of these miRNAs in non-neoplastic rectal mucosa from UC patients could identify those patients at greatest risk for developing UC-CRC (Supplementary Figure 1).

The diagnosis of UC was based on medical history, endoscopic findings, histologic examination, laboratory tests, and clinical disease presentation. The extent of disease was characterized as left-side colitis or total colitis, and inflammation severity was classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings. Patients with right-sided colitis, segmental colitis and proctitis, acute fulminating UC, those who presented with their first attacks, or infectious colitis caused by C. difficile or cytomegalovirus were excluded from evaluation.

In the clinical evaluation cohort, 62 patients had only colitis, while 25 also had UC-associated dysplasia or cancer (Supplementary Table 1). During surveillance colonoscopy, target biopsies were obtained from regions suspected of UC-CRC. Panchromoendoscopy was not performed routinely. However, chromoendoscopy was performed for any lesion suspected of dysplasia or cancer. Although high-definition colonoscopy was only used at the endoscopists’ discretion, the majority of endoscopists utilized high-definition white-light endoscopes in 100% of cases. The number of targeted biopsy samples was not limited, but features prompting biopsy included protruding lesions, flat lesions, and depressed lesions. All biopsied specimens were confirmed histopathologically by 2 expert pathologists. The pathologic findings were categorized as: the absence of neoplasia, low-grade dysplasia, and high-grade dysplasia or cancer. In the event of a discrepancy among the pathologists, the final diagnosis was made based on mutual discussion.

All fresh frozen tissues retrieved from colectomy specimens came from the Mie University Hospital between 2005 and 2015. In UC patients without dysplasia or cancer, multiple tissue specimens were sampled from 3 different regions within the colon (cecum, transverse colon, and rectum). Likewise, 2 specimens (neoplastic tissue and rectal epithelium without dysplasia or cancer) were collected from patients with dysplasia or cancer (Supplementary Figure 1). All tissue specimens were preserved immediately after surgical resection and stored at −80°C until DNA extraction.

In the external validation cohort, 90 patients had only colitis, while 61 patients also had UC-associated dysplasia or cancer (Supplementary Table 2). In this cohort, non-neoplastic rectal epithelium was collected from UC patients with and without dysplasia or cancer (Supplementary Figure 1). All tissues were formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE), and retrieved from colectomy specimens resected at the Hyogo College of Medicine between 2005 and 2011. Specimen collection and studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of all participating institutions. All participants provided written informed consent and willingness to donate their tissue samples for research.

DNA Extraction From Fresh-Frozen Samples and FFPE Samples

DNA from fresh-frozen surgical specimens was isolated using QIAmp DNA Mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. FFPE tissue blocks were serially sectioned at 10 μm thickness. Based on histologic findings, mucosal tissues from each region were microdissected and genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAmp DNA FFPE tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

DNA Methylation Analysis

DNA was bisulfite modified using the EZ DNA methylation Gold Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Methylation status of putative promoter regions of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C were quantified by quantitative bisulfite pyrosequencing (PSQ HS 96A pyrosequencing system; Qiagen), and the primers sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Methylation levels of each specimen were represented as the mean methylation levels of specific CpG sites analyzed within the promoter regions of each miRNA (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from FFPE tissues using the RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Ambion Inc, Austin, TX). Briefly, tissue sections were microdissected to enrich for neoplastic cells, followed by deparaffinization and RNA extraction using the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA was eluted in the appropriate buffer, and quantified using a Nano-Drop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Reverse transcription reactions were carried out using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a total reaction volume of 15 μL. MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, MIR34C, and MIR16 were quantified in duplicate by qRT-PCR, using MicroRNA Assay Kits (Applied Biosystems). qRT-PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7000 Sequence Detection System. MIR16 was chosen as the endogenous normalizer for miRNA expression analysis based on previous findings that MIR16 was one of the most suitable reference genes for relative quantification of small ncRNAs in colonic tissues based on microarray analysis of large cohorts of normal and neoplastic tissues, as well as our own studies illustrating that MIR16 is a reliable normalizer for tissue colorectal tissues.25–31 Expression levels of tissue miRNAs were normalized against MIR16 using the 2–ΔCt method. Differences between the groups were presented as ΔCt, indicating differences between Ct values of the miRNA of interest and those of the normalizer miRNA.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical differences in tissue miRNA methylation and expression levels between different sample sources were determined using Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests, as appropriate, based on the non-normal distribution of the methylation levels observed. Statistical differences in miRNA methylation levels between different sampling locations (cecum, transverse colon, and rectum) from the same group of patients were compared using the Wilcoxon test for paired samples. Differences in the methylation levels in each disease location by clinical variables (gender, age at diagnosis, age at operation, disease duration, the degree of inflammation, and colitis type) were compared using the Mann-Whitney’s U test after stratifying the entire cohort into below and above the median of each clinical variable. F-tests were used to assess the equality of variance for comparable groups. When multiple hypothesis testing was performed, the P value for significance was adjusted by Bonferroni correction in each analysis respectively. Differences between categorized groups were estimated by the Pearson’s χ2-test. Results were expressed as median ΔIQRs (interquartile ranges). The Spearman’s rank correlation test was conducted for statistical correlations. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were established to distinguish UC patients with and without dysplasia or cancer. Diagnostic criteria were used as per STARD guidelines, and predictive accuracy was determined by measuring area under the ROC curve (AUC), specificity, and sensitivity. A predictive model with AUC of Δ0.7 was considered to be sufficiently discriminative; AUC of 0.5 is equivalent to a “coin toss.”32,33 Optimal cutoff values of miRNA methylation levels in logistic regression analysis for predictive factors of UC-dysplasia or cancer were determined by ROC curves with Youden’s index. For the individual ROC analyses, we used the actual proportion of methylation level of each miRNA and generated the ROC curve with a moving threshold because all the miRNAs fulfilled the criteria of AUC >0.7 in the individual analyses; and since there were no significant collinearities between the methylation statuses of the miRNAs, we used the methylation levels of all miRNAs in the combined ROC analysis. Logistic regression models produced odds ratio and, based on these data, a linear function was constructed in each cohort to produce the scoring for combined ROC analysis to determine the clinical significance for using methylation levels of this miRNA panel in the rectal mucosa as potential biomarkers for patients at risk for UC-associated dysplasia or cancer. Other clinical variables considered for logistic regression analysis included gender, age at onset of disease, age at time of surgery, disease duration, extent of disease, and inflammation score. Forced-entry regression was used to include these variables in all multivariable equations to analyze whether each of the predictors affected the outcome after adjusting for known confounders. With regard to the co-linearity between the variables, those with Pearson’s correlation coefficients above 0.5 or below −0.5 were regarded as highly co-linear. In the validation cohort, we used all the covariates used in the first discovery cohort that were clinically available in the corresponding cohort. All P values are 2-sided. P < .05 was considered significant in multivariate analysis. All statistical analyses were carried out using Medcalc 12.7 software (Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Methylation Levels of miRNAs in Mucosa From UC Patients Without Neoplasia Were Significantly Associated With Age, Disease Duration, and Location Within the Colorectum

We evaluated associations between methylation levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C and clinicopathologic features in mucosal tissues from UC patients without dysplasia or cancer based on their location within the colorectum (n=186). MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C methylation levels showed a stepwise increase in methylation from cecum to rectum; and methylation levels of 4 miRNAs (all except MIR34B/C) were significantly higher in rectal mucosa vs cecum (MIR1: 10.0 ± 3.0% vs 10.0 ± 2.0%, P = .002; MIR9: 11.0 ± 6.0% vs 8.0 ± 4.0%, P < .001; MIR124: 8.0 ± 5.0% vs 6.0 ± 2.0%, P = .002; MIR137: 6.5 ± 3.0% vs 5.0 ± 1.0%, P < .001; MIR34B/ C: 13.5 ± 8.0% vs 13.0 ± 7.0%, P = .017; Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C methylation levels in UC mucosa (n = 186). Dot plots depicting methylation levels of miRNAs in mucosa from the cecum (C; n=62), transverse colon (T; n=62), and rectum (R; n=62) (MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C, respectively). Statistically significant differences were determined using Mann–Whitney tests and Kruskal–Wallis tests. When multiple hypothesis testing was performed, the P value for significance was adjusted to .017 (= .05/3) by Bonferroni correction. (B) MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C methylation levels in UC mucosa by disease status (n = 236). Dot plots illustrating miRNA methylation levels in non-neoplastic UC mucosa (N; n=211), dysplasia (D; n=12), and cancer (C; n=13) (MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C, respectively). Statistically significant differences were determined using Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests. When multiple hypothesis testing was performed, the P value for significance was adjusted to .017 (= .05/3) by Bonferroni correction.

Furthermore, methylation levels of 4 miRNAs that were methylated in a location-dependent manner demonstrated a significant association with age at diagnosis (MIR1: 12.0 ± 3.0 vs 10.0 ± 2.0, P = .001; MIR9: 12.0 ± 6.0 vs 9.0 ± 4.0, P = .002; MIR124: 9.0 ± 5.5 vs 6.0 ± 3.8, P = .001; MIR137: 7.0 ± 3.0 vs 6.0 ± 3.0, P < .001), and age at operation (MIR1: 12.0 ± 3.0 vs 10.0 ± 2.0, P = .001; MIR9: 12.0 ± 7.5 vs 9.0 ± 4.0, P = .002; MIR124: 9.0 ± 6.0 vs 6.0 ± 3.8, P = .002; MIR137: 7.0 ± 3.0 vs 6.0 ± 3.0, P < .001) in rectal mucosa. Particularly, longer disease duration was significantly associated with hypermethylation of MIR124 in rectal mucosa (MIR1: 12.0 ± 3.0 vs 10.0 ± 2.5, P = .011; MIR9: 12.0 ± 7.0 vs 10.0 ± 4.5, P = .026; MIR124: 9.0 ± 7.0 vs 6.5 ± 3.8, P = .008; MIR137: 7.0 ± 3.0 vs 6.0 ± 2.0, P = .009) in rectal mucosa (Table 1, and Supplementary Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7). In contrast, no associations were observed between MIR34B/C methylation and any of the clinicopathologic features (Supplementary Table 8), suggesting that aberrant methylation of specific miRNAs occurs in a location- and age-dependent manner in rectal mucosa of UC patients.

Table 1.

Correlation Between Clinicopathologic Factors and miRNA Methylation Status in UC Rectal Mucosa

| Methylation levels in rectal mucosa (median ± IQRs) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Category | MIR1 | P | MIR9 | P | MIR124 | P | MIR137 | P | MIR34B/C | P | |

| Gender | Male | 10.0 ± 3.5 | .54 | 10.0 ± 4.0 | .86 | 7.0 ± 5.0 | .93 | 6.0 ± 3.0 | .11 | 13.0 ± 8.0 | .59 |

| Female | 10.5 ± 4.0 | 11.0 ± 7.0 | 8.0 ± 5.0 | 7.0 ± 2.0 | 14.0 ± 6.5 | ||||||

| Smoking history | Present | 10.5 ± 3.0 | .69 | 11.0 ± 5.0 | .97 | 8.0 ± 5.0 | .85 | 6.5 ± 2.0 | .92 | 13.0 ± 7.0 | .67 |

| Absent | 10.0 ± 3.0 | 10.5 ± 5.5 | 7.5 ± 5.5 | 6.5 ± 3.0 | 14.0 ± 7.5 | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis | ≤ 27 ya | 10.0 ± 2.0 | .001 | 9.0 ± 4.0 | .002 | 6.0 ± 3.8 | .001 | 6.0 ± 3.0 | <.001 | 12.0 ± 9.8 | .1 |

| > 27 ya | 12.0 ± 3.0 | 12.0 ± 6.0 | 9.0 ± 5.5 | 7.0 ± 3.0 | 15.0 ± 4.0 | ||||||

| Age at operation | ≤ 34 ya | 10.0 ± 2.0 | .001 | 9.0 ± 4.0 | .002 | 6.0 ± 3.8 | .002 | 6.0 ± 3.0 | <.001 | 13.0 ± 8.8 | .24 |

| > 34 ya | 12.0 ± 3.0 | 12.0 ± 7.5 | 9.0 ± 6.0 | 7.0 ± 3.0 | 14.0 ± 4.8 | ||||||

| Disease duration | ≤ 6 ya | 10.0 ± 2.5 | .011 | 10.0 ± 4.5 | .026 | 6.5 ± 3.0 | .008 | 6.0 ± 2.0 | .009 | 13.0 ± 8.0 | .17 |

| > 6 ya | 12.0 ± 3.0 | 12.0 ± 7.0 | 9.0 ± 7.0 | 7.0 ± 3.0 | 14.0 ± 8.0 | ||||||

| Inflammation degree | mild | 10.0 ± 4.0 | .82 | 10.0 ± 4.5 | .2 | 7.0 ± 5.3 | .96 | 7.0 ± 3.3 | .58 | 13.0 ± 7.3 | .94 |

| moderate/severe | 10.0 ± 3.0 | 11.0 ± 6.3 | 8.0 ± 5.3 | 6.0 ± 3.0 | 14.0 ± 7.3 | ||||||

| Colitis type | left side | 11.0 ± 2.5 | .69 | 11.0 ± 5.5 | .47 | 8.0 ± 4.8 | .38 | 7.0 ± 2.8 | .13 | 13.0 ± 5.5 | .93 |

| total | 10.0 ± 3.3 | 10.0 ± 5.5 | 7.0 ± 5.0 | 6.0 ± 3.0 | 14.0 ± 8.0 | ||||||

NOTE. When multiple hypothesis testing was performed, the P value for significance was adjusted to .0083 (= .05/6) by Bonferroni correction. Bold values indicate statistical significance.

The median age at onset, median age at surgery and median disease duration are 27, 34, and 6 years, respectively.

Methylation Levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C Were Significantly Higher in Neoplastic vs Non-neoplastic Tissues in UC Patients

To evaluate the diagnostic potential of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C methylation levels, we examined 236 tissue specimens, which included 211 UC mucosa and 25 UC-associated neoplastic tissues (12 with dysplasia and 13 with CRC) in the clinical evaluation cohort. Compared with UC mucosa, methylation levels of all of 5 miRNAs were increased in cancer tissues (MIR1: 21.0 ±19.3 vs 10.0 ±3.0, P <.001; MIR9: 23.0 ±11.5 vs 10.0 ±5.0, P <.001; MIR124: 35.0 ±23.5 vs 7.0 ± 3.0, P < .001; MIR137: 24.0 ± 16.3 vs 6.0 ± 3.0, P < .001; MIR34B/C: 35.0 ± 23.0 vs 14.0 ± 8.0, P < .001; Figure 1B). Likewise, the methylation of these miRNAs was significantly increased in dysplasia compared with non-neoplastic UC mucosa (MIR1: 13.5 ± 3.0 vs 10.0 ± 3.0, P = .004; MIR9: 13.5 ± 4.0 vs 10.0 ± 5.0, P < .001; MIR124: 12.0 ± 6.5 vs 7.0 ± 3.0, P < .001; MIR137: 10.5 ± 4.0 vs 6.0 ± 3.0, P < .001; MIR34B/ C: 23.5 ± 6.5 vs 14.0 ± 8.0, P < .001; Figure 1B).

ROC analyses revealed that methylation levels of each individual miRNA were robust in discriminating cancer from UC mucosa, as evidenced by high sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), and AUC values of MIR1 (sensitivity: 84.6%, specificity: 85.8%, positive predictive value (PPV): 26.8%, NPV: 98.9%, AUC: 0.92), MIR9 (sensitivity: 84.6%, specificity: 88.6%, PPV: 31.4%, NPV: 98.9%, AUC: 0.94), MIR124 (sensitivity: 100%, specificity: 82.9%, PPV: 26.5%, NPV: 100%, AUC: 0.98), MIR137 (sensitivity: 84.6%, specificity: 97.6%, PPV: 68.7%, NPV: 99.0%, AUC: 0.98) and MIR34B/C (sensitivity: 100%, specificity: 89.1%, PPV: 36.1%, NPV: 100%, AUC: 0.98), respectively (Figure 2A). More importantly, from a diagnostic perspective, methylation levels of all 5 miRNAs reliably differentiated dysplasia from UC mucosa, as evidenced by the high NPV values of 98.2% (MIR1, sensitivity: 75.0%, specificity: 79.1%, PPV: 17.0%, AUC: 0.75), 99.2% (MIR9, sensitivity: 91.7%, specificity: 60.2%, PPV: 11.6%, AUC: 0.8), 98.2% (MIR124, sensitivity: 75.0%, specificity: 79.6%, PPV: 17.3%, AUC: 0.79), 98.9% (MIR137, sensitivity: 83.3%, specificity: 84.4%, PPV: 23.2%, AUC: 0.91) and 98.9% (MIR34B/C, sensitivity: 83.3%, specificity: 87.2%, PPV: 27.0%, AUC: 0.9), respectively (Figure 2A). Additionally, ROC analysis using a combination of methylation levels from all miRNAs revealed that this panel was very robust in discriminating UC-associated neoplasia from non-neoplastic UC mucosa (AUC values of 0.99 for UC-associated cancer, 0.94 for dysplasia, and 0.97 for all neoplasia [dysplasia or cancer], Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) ROC curve analysis for methylation levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C in distinguishing UC-associated dysplasia or cancer from non-neoplastic UC mucosa. AUC, area under the curve; Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value. ROC curve analyses demonstrate that methylation levels of all 5 miRNAs are robust in discriminating cancer from UC mucosa, with high sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and AUC values of MIR1 (Sensitivity: 84.6%, Specificity: 85.8%, PPV: 26.8%, NPV: 98.9%, AUC: 0.92), MIR9 (Sensitivity: 84.6%, Specificity: 88.6%, PPV: 31.4%, NPV: 98.9%, AUC: 0.94), MIR124 (Sensitivity: 100%, Specificity: 82.9%, PPV: 26.5%, NPV: 100%, AUC: 0.98), MIR137 (Sensitivity: 84.6%, Specificity: 97.6%, PPV: 68.7%, NPV: 99.0%, AUC: 0.98) and MIR34B/C (Sensitivity: 100%, Specificity: 89.1%, PPV: 36.1%, NPV: 100%, AUC: 0.98), respectively, in the upper panels. The lower panels represent ROC curve analyses for methylation levels of miRNAs in discriminating dysplasia from UC mucosa, with high NPV and AUC values of MIR1 (Sensitivity: 75.0%, Specificity: 79.1%, PPV: 17.0%, NPV: 98.2%, AUC: 0.75), MIR9 (Sensitivity: 91.7%, Specificity: 60.2%, PPV: 11.6%, NPV: 99.2%, AUC: 0.8), MIR124 (Sensitivity: 75.0%, Specificity: 79.6%, PPV: 17.3%, NPV: 98.2%, AUC: 0.79), MIR137 (Sensitivity: 83.3%, Specificity: 84.4%, PPV: 23.2%, NPV: 98.9%, AUC: 0.91) and MIR34B/C (Sensitivity: 83.3%, Specificity: 87.2%, PPV: 27.0%, NPV: 98.9%, AUC: 0.9), respectively. (B) Combination analysis for methylation levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C in discriminating dysplasia or cancer from non-neoplastic UC mucosa. Combined ROC analyses for the methylation levels of various miRNAs revealed a significantly improved AUC value of 0.99 (95% CI: 0.97–0.99) with 100% sensitivity and 95.7% specificity in discriminating UC-associated cancer (left panel), 0.94 (95% CI: 0.9–0.97) with 100% sensitivity and 77.3% specificity in discriminating UC-associated dysplasia (middle panel), and 0.97 (95% CI: 0.94–0.99) with 92.0% sensitivity and 95.3% specificity in discriminating UC-associated neoplasia (dysplasia or cancer; right panel).

A Panel of Methylated miRNAs From Rectal Mucosa Could Identify UC Patients With Dysplasia or Cancer

To assess the potential usefulness of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C methylation as biomarkers for the early diagnosis of UC-associated CRC, we compared methylation in non-neoplastic rectal mucosa from UC patients with and without neoplasia. We observed that methylation of each of the miRNAs in rectal mucosa was significantly higher in patients with cancer than in those without (MIR1: 17.0 ± 10.0 vs 10.0 ± 3.0, P < .001; MIR9: 15.0 ± 7.0 vs 11.0 ± 6.0, P = .027; MIR124: 13.0 ± 7.0 vs 8.0 ± 5.0, P = .003; MIR137: 10.0 ± 5.8 vs 6.5 ± 3.0, P < .001; MIR34B/C: 19.0 ± 6.0 vs 13.5 ± 8.0, P < .001; Table 2). In addition, MIR1, MIR137, and MIR34B/C methylation in rectal mucosa from patients with dysplasia or cancer was significantly higher compared with methylation in patients without neoplasia (MIR1: 17.0 ± 6.0 vs 10.0 ± 3.0, P = .003; MIR137: 9.0 ± 2.8 vs 6.5 ± 3.0, P < .001; MIR34B/C: 17.0 ± 6.3 vs 13.5 ± 8.0, P = .005; Table 2). These results support that methylation of these miRNAs reflect an underlying field defect in UC mucosa.

Table 2.

Methylation Levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C in Non-neoplastic Rectal Tissue of Patients who Have UC, With and Without Dysplasia or Cancer in the Clinical Evaluation Cohort

| Category | Patients without cancer (n = 62) | Patients with cancer (n = 13) | P | Patients without dysplasia or cancer (n = 62) | Patients with dysplasia or cancer (n = 25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIR1 methylation (median ± IQRs) | 10.0 ± 3.0 | 17.0 ± 10.0 | <.001 | 10.0 ± 3.0 | 17.0 ± 6.0 | .003 |

| MIR9 methylation (median ± IQRs) | 11.0 ± 6.0 | 15.0 ± 7.0 | .027 | 11.0 ± 6.0 | 12.0 ± 5.8 | .05 |

| MIR124 methylation (median IQRs) | 8.0 ± 5.0 | 13.0 ± 7.0 | .003 | 8.0 ± 5.0 | 9.0 ± 6.8 | .13 |

| MIR137 methylation (median ± IQRs) | 6.5 ± 3.0 | 10.0 ± 5.8 | <.001 | 6.5 ± 3.0 | 9.0 ± 2.8 | <.001 |

| MIR34B/C methylation (median ± IQRs) | 13.5 ± 8.0 | 19.0 ± 6.0 | <.001 | 13.5 ± 8.0 | 17.0 ± 6.3 | .005 |

NOTE. Neoplasia: dysplasia or cancer. When multiple hypothesis testing was performed, the P value for significance was adjusted to .01 (= .05/5) by Bonferroni correction. Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Next, we generated ROC curves to determine the clinical significance of using this miRNA methylation panel in rectal mucosa as biomarkers in patients at risk for UC-associated CRC. ROC analyses revealed that methylation of these miRNAs robustly discriminated UC patients with vs without cancer, with high NPV and AUC values of MIR1 (sensitivity: 84.6%, specificity: 75.8%, PPV: 42.3%, NPV: 95.9%, AUC: 0.84), MIR9 (sensitivity: 61.5%, specificity: 77.4%, PPV: 36.3%, NPV: 90.6%, AUC: 0.7), MIR124 (sensitivity: 76.9%, specificity: 67.7%, PPV: 33.3%, NPV: 93.3%, AUC: 0.76), MIR137 (sensitivity: 76.9%, specificity: 80.6%, PPV: 45.5%, NPV: 94.3%, AUC: 0.8) and MIR34B/C (sensitivity: 100%, specificity: 56.5%, PPV: 32.5%, NPV: 100%, AUC: 0.8), respectively (Figure 3A). These results consistently revealed high NPVs and low PPVs in these analyses, suggesting that hypermethylation of these miRNAs could be used as a biomarker for diagnosis of UC patients with cancer.

Figure 3.

(A) ROC curve analysis demonstrated that methylation levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C in non-neoplastic rectal mucosa could distinguish patients with UC-associated neoplasia from those without in the clinical evaluation cohort. AUC, area under the curve; Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value. The upper panels represent ROC curve analyses of miRNA methylation discriminating UC patients with cancer from those without cancer, with high NPV and AUC values of MIR1 (Sensitivity: 84.6%, Specificity: 75.8%, PPV: 42.3%, NPV: 95.9%, AUC: 0.84), MIR9 (Sensitivity: 61.5%, Specificity: 77.4%, PPV: 36.3%, NPV: 90.6%, AUC: 0.7), MIR124 (Sensitivity: 76.9%, Specificity: 67.7%, PPV: 33.3%, NPV: 93.3%, AUC: 0.76), MIR137 (Sensitivity: 76.9%, Specificity: 80.6%, PPV: 45.5%, NPV: 94.3%, AUC: 0.8), and MIR34B/C (Sensitivity: 100%, Specificity: 56.5%, PPV: 32.5%, NPV: 100%, AUC: 0.8), respectively. The lower panels demonstrate ROC curve analyses for methylation levels of these miRNAs in differentiating UC patients with cancer or dysplasia from those without, with corresponding AUC values of 0.7 (MIR1: Sensitivity: 84.0%, Specificity: 53.2%, PPV: 42.0%, NPV: 89.2%), 0.63 (MIR9: Sensitivity: 88.0%, Specificity: 38.7%, PPV: 36.7%, NPV: 88.9%), 0.61 (MIR124: Sensitivity: 24.0%, Specificity: 95.2%, PPV: 66.7%, NPV: 75.6%), 0.77 (MIR137: Sensitivity: 76.0%, Specificity: 71.0%, PPV: 51.4%, NPV: 88.0%), and 0.69 (MIR34B/C: Sensitivity: 84.0%, Specificity: 50.0%, PPV: 40.4%, NPV: 88.6%), respectively. (B) Combined ROC analysis revealed that methylation panel of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137,and MIR34B/C inrectalnon-neoplastic mucosa could discriminate UC patients with neoplasia from those without in the clinical evaluation cohort. Combined ROC analyses for methylation levels revealed AUC values of0.85(95%CI: 0.75–0.92) with92.3% sensitivity and62.9% specificityindiscriminating UC-associated cancer (left panel), 0.80 (95% CI: 0.69–0.88) with 83.3% sensitivity and 69.4% specificity in discriminating UC-associated dysplasia (middle panel), and 0.81 (95% CI: 0.71–0.88) with 80.0% sensitivity and 74.2% specificity in discriminating UC-associated dysplasia or cancer (right panel). (C) ROC curve analysis demonstrated that methylation levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C in non-neoplastic rectal mucosa could distinguish patients with UC-associated neoplasia from those without in the external validation cohort. The upper panels represent ROC curve analysis of miRNA methylation discriminating UC patients with cancer from those without cancer, with high NPV and AUC values of MIR1 (Sensitivity: 58.2%, Specificity: 81.1%, PPV: 65.3%, NPV: 76.0%, AUC: 0.71), MIR9 (Sensitivity: 82.1%, Specificity: 51.1%, PPV: 51.1%, NPV: 82.1%, AUC: 0.7), MIR124 (Sensitivity: 78.6%, Specificity: 60.0%, PPV: 55.0%, NPV: 81.8%, AUC: 0.68), MIR137 (Sensitivity: 85.7%, Specificity: 57.8%, PPV: 55.8%, NPV: 86.7%, AUC: 0.77), and MIR34B/C (Sensitivity: 76.8%, Specificity: 56.7%, PPV: 52.4%, NPV: 79.7%, AUC: 0.7), respectively. (D) Combined ROC analysis revealed that methylation panel of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C in rectal non-neoplastic mucosa could discriminate UC patients with neoplasia from those without in the external validation cohort. Combined ROC analyses for the methylation levels revealed AUC values of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.71–0.85) with 67.3% sensitivity and 82.2% specificity in discriminating UC-associated cancer (left panel), and 0.78 (95% CI: 0.7–0.84) with 65.0% sensitivity and 81.1% specificity in discriminating UC-associated dysplasia or cancer (right panel).

More importantly, from a screening perspective, the methylation status of MIR137 alone in rectal mucosa could differentiate UC patients with dysplasia or cancer from those without neoplasia, with an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.67–0.86), with a sensitivity and specificity of 76.0% and 71.0%, respectively (Figure 3A). These results were further strengthened by univariate logistic regression analysis illustrating that elevated methylation of all 5 miRNAs together with disease duration >8 years could be used to assess the risk for developing UC-associated CRC (Supplementary Table 9).

Thereafter, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to further clarify the ability of these miRNA biomarkers to serve as independent risk factors for identifying UC patients at high risk for UC-CRC by using the forced-entry model that included covariates based on the results of co-linearity between the variables (Supplementary Table 10). The results of this analysis revealed that high MIR137 methylation levels in rectal mucosa may serve as an independent risk factor for UC patients harboring dysplasia or cancer (OR: 5.92, 95% CI: 1.36–25.8, P = .018; Supplementary Table 9). Furthermore, combined ROC analysis for a methylation panel of these miRNAs in rectal mucosa successfully identified patients harboring UC-CRC with remarkably high AUC values (cancer: 0.85 [95% CI: 0.75–0.92]; dysplasia: 0.8 [95% CI: 0.69–0.88], and dysplasia or cancer: 0.81 [5% CI: 0.71–0.88]); Figure 3B).

Methylation of miRNAs in Rectal Mucosa From UC Patients With Neoplasia in an Independent Patient Cohort

Finally, to confirm the biomarker potential of these miRNAs as biomarkers for risk assessment of UC patients harboring dysplasia or cancer, we evaluated the methylation status of these miRNAs in non-neoplastic rectal mucosa from UC patients with and without neoplasia using clinical specimens from an independent patient cohort of UC-CRC. Methylation of all 5 miRNAs in rectal mucosa was significantly higher in patients with CRC, or dysplasia and cancer, than in those with neither (MIR1: 11.2 ±9.2 vs 6.4 ±6.4, P <.001, 11.0 ±9.2 vs 6.4 ± 6.4, P < .001; MIR9: 14.3 ± 8.5 vs 10.5 ± 5.7, P < .001, 13.8 ± 7.5 vs 10.5 ± 5.7, P < .001; MIR124: 25.4 ± 15.2 vs 18.3 ± 18.8, P <.001, 24.8 ± 14.9 vs 18.3 ± 18.8, P < .001; MIR137: 14.0 ± 6.6 vs 9.4 ± 5.3, P < .001, 13.3 ± 6.7 vs 9.4 ± 5.3, P < .001; MIR34B/C: 24.9 ± 7.0 vs 21.3 ± 7.0, P < .001, 24.5 ± 6.8 vs 21.3 ± 7.0, P < .001, respectively; Table 3).

Table 3.

Methylation Levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C in Non-neoplastic Rectal Tissue of Patients who have UC, With and Without Dysplasia or Cancer in an External Validation Cohort

| Category | Patients without cancer (n = 90) | Patients with cancer (n = 56) | P | Patients without dysplasia or cancer (n = 90) | Patients dysplasia or cancer (n = 61) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIR1 methylation (median ± IQRs) | 6.4 ± 6.4 | 11.2 ± 9.2 | <.001 | 6.4 ± 6.4 | 11.0 ± 9.2 | <.001 |

| MIR9 methylation (median ± IQRs) | 10.5 ± 5.7 | 14.3 ± 8.5 | <.001 | 10.5 ± 5.7 | 13.8 ± 7.5 | <.001 |

| MIR124 methylation (median± IQRs) | 18.3 ± 18.8 | 25.4 ± 15.2 | <.001 | 18.3 ± 18.8 | 24.8 ± 14.9 | <.001 |

| MIR137 methylation (median± IQRs) | 9.4 ± 5.3 | 14.0 ± 6.6 | <.001 | 9.4 ± 5.3 | 13.3 ± 6.7 | <.001 |

| MIR34B/C methylation (median± IQRs) | 21.3 ± 7.0 | 24.9 ± 7.0 | <.001 | 21.3 ± 7.0 | 24.5 ± 6.8 | <.001 |

NOTE. Neoplasia: dysplasia or cancer. When multiple hypothesis testing was performed, the P value for significance was adjusted to .01 (= .05/5) by Bonferroni correction. Bold values indicate statistical significance.

We performed ROC analysis to validate the potential of this miRNA panel in rectal mucosa as biomarkers for identification of UC patients harboring dysplasia or cancer. ROC analyses revealed that methylation levels of these miRNAs could discriminate UC patients with vs without cancer or dysplasia with AUC values similar to those observed in our clinical evaluation cohort (MIR1: 0.7; MIR9: 0.69, MIR124: 0.67; MIR137: 0.76; MIR34B/C: 0.7) (Figure 3C). In addition, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the methylation status of MIR137, MIR34B/C, and MIR124 in rectal mucosa can serve as an independent risk factor for UC patients harboring dysplasia or cancer (MIR137, OR: 3.34, 95% CI: 1.38–8.05, P = .007; MIR34B/C, OR: 2.87, 95% CI: 1.23–6.69, P = .014; MIR124, OR: 2.63, 95% CI: 1.01–6.86, P = .048; Supplementary Table 11). Combined ROC analysis for a methylation panel of these miRNAs in rectal mucosa also successfully validated the biomarker potential for identifying patients harboring UC-associated cancer with remarkably high specificity, NPV, and AUC values (Cancer: sensitivity: 67.3%, specificity: 82.2%, PPV: 69.9%, NPV: 80.7%, AUC: 0.78 (95% CI: 0.71–0.85), and combined cancer or dysplasia: sensitivity: 65.0%, specificity: 81.1%, PPV: 69.6%, NPV: 77.7%, AUC: 0.78 (95% CI: 0.7–0.84); Figure 3D).

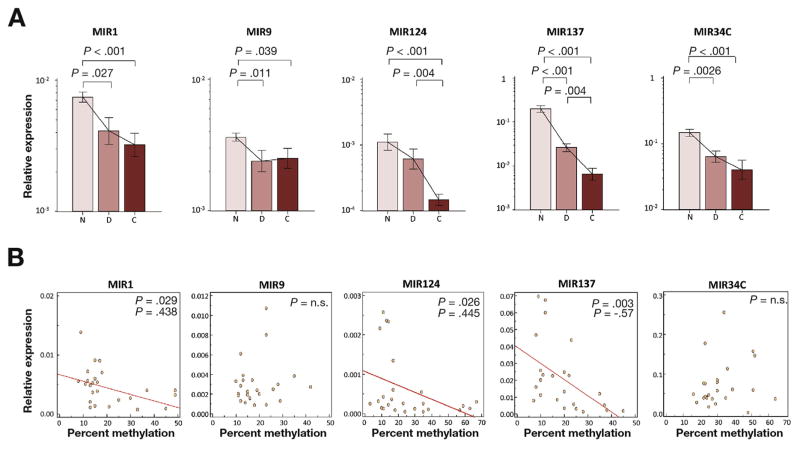

Inverse Correlation Between Methylation Levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C and Their Expression

To determine whether methylation of these miRNAs also resulted in transcriptional silencing of their expression in UC tissues, we quantified expression levels of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34C in dysplastic, cancerous, and non-neoplastic UC mucosa. As expected, compared with non-neoplastic UC mucosa, expression of all 5 miRNAs demonstrated a stepwise decrease in dysplasia (MIR1: P = .027; MIR9: P = .011; MIR137: P < .001; MIR34C: P = .0026), and/or in cancer (MIR1: P < .001; MIR9: P = .039; MIR124: P < .001; MIR137: P < .001; MIR34C: P < .001, Figure 4A). Methylation and expression of MIR1, MIR124, and MIR137 were significantly and inversely correlated with UC-associated dysplasia or cancer (MIR1; ρ= −0.438, P = .029, MIR124; ρ= −0.445, P = .026, MIR137; ρ= −0.57, P = .003, Figure 4B). In contrast, an inverse correlation was not observed for MIR9 or MIR34B/C methylation levels and expression status in UC-associated dysplasia or cancer.

Figure 4.

Expression of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34C in tissues from UC patients. (A) Expression levels of age-associated miRNAs in non-neoplastic UC mucosa (N, n=20), dysplasia (D, n=12), and cancer (C, n=13). The Y-axis represents relative expression of miRNAs normalized to MIR16 expression. Statistically significant differences were determined using Mann–Whitney tests and Kruskal–Wallis tests. When multiple hypothesis testing was performed, the P value for significance was adjusted to .017 (= .05/3) by Bonferroni correction. (B) Scatter plots of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, MIR137, and MIR34B/C show correlations between expression levels (Y-axis) and methylation levels (X-axis) in samples obtained from UC patients with dysplasia and cancer. Negative correlations were found for MIR1, MIR124, and MIR137 by Spearman correlation (MIR1; ρ= −0.44, P = .029, MIR124; ρ= −0.445, P = .026, MIR137; ρ= −0.57, P = .003).

Discussion

We embarked upon this study to investigate whether the methylation status in a panel of miRNAs in tissues from patients with UC could be used as diagnostic biomarkers for identifying patients at higher risk of UC-CRC. Although some previous studies have attempted to identify disease-specific and site-specific patterns of miRNA dysregulation and altered DNA methylation in UC/UC-CRC,14,34–37 these have achieved limited success because of the use of improperly designed study cohorts and the lack of optimal candidate markers. Based upon our results, we made several important clinically relevant observations. First, methylation of MIR1, MIR9, MIR124, and MIR137 in rectal mucosa from UC patients was significantly higher compared with 2 other proximal regions in the colon. Second, methylation in this miRNA panel significantly associated with various clinical factors, including the age at diagnosis, age at operation, and disease duration, and this pattern was most pronounced in rectal tissues. Third, we found that methylation of each of the miRNAs was significantly higher in patients with dysplasia or cancer compared with that in non-neoplastic UC mucosa. Fourth, methylation of all miRNAs in the rectal mucosa from UC patients with dysplasia or cancer were significantly higher than those without, and these results were successfully validated in second, independent patient cohort. Taken together, methylation status of our miRNA panel in UC mucosa revealed malignancy- and age–related alterations, as well as reinforced existence of a field defect in the rectum of UC patients.

Another important clinical implication of this study is that methylation of these miRNAs emerged as novel biomarkers for identifying patients who are at a higher risk of UC-associated dysplasia or cancer. We confirmed that methylation in this miRNA panel in rectal mucosa was significantly higher in patients with cancer than in those without, particularly in the subset of patients with a disease duration >8 years (Supplementary Table 12), for whom surveillance colonoscopy for UC-associated CRC is strongly recommended.1,38 In addition, our ROC analysis revealed higher AUC values for methylation of each miRNA in rectal tissues from UC patients with vs those without cancer, and these AUC values were superior to the data for disease duration. Furthermore, our miRNA-methylation assay was better in refuting dysplasia and cancer rather than their prediction because ROC analysis revealed that while NPV was greater than 90%, the PPV was lower. Collectively, our methylated miRNA biomarkers appear to be robust for diagnosing patients with UC-CRC, and may help improve the current approach to colonoscopic surveillance for identifying patients that are truly at greater risk of neoplasia. Furthermore, surveillance colonoscopy is invasive, cumbersome, and expensive, and leads to poor screening compliance, and the clinical efficacy of such a screening protocol for reducing the risk of UC-CRC remains controversial.39 Therefore, surveillance colonoscopy following our miRNA methylation assay could be developed into a more cost-effective and less invasive approach to managing UC patients with longstanding disease, and offer them a more robust and practical strategy compared with what we now use.

Our data also demonstrated that methylation levels of MIR137 alone had a robust AUC in discriminating patients with UC-associated dysplasia or cancer, and emerged as an independent marker for UC-associated neoplasia. However, UC-CRC progression is a multistep process that involves the accumulation of heterogeneous genetic and epigenetic alterations, creating a challenge for the development of a single biomarker that can adequately capture disease heterogeneity. In view of this evidence, we noted that in contrast to analyzing the methylation status of each miRNA individually, a combined methylation analysis using this miRNA panel could further improve the diagnostic accuracy for the identification of UC patients harboring dysplasia or cancer.

The precise function of the miRNAs in our study have already been characterized as tumor suppressive in various human cancers. The onco-suppressive role of MIR1 has been indicated in several human cancers.23,40,41 wherein it exerts its activity by directly targeting several oncogenes, such as MET, FOXP1, HDAC4, and BDNF.17,41–43 Silence of MIR9 by CpG island hypermethylation has been reported previously, and MIR9 possesses tumor suppressor and anti-inflammatory potential by targeting cyclin D1, Ets1, CXCR4, and NFkB1.20,44,45 Likewise, MIR124 is thought to exert a tumor-suppressive effect by targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6); and epigenetic silencing of MIR124 leads to CDK6 activation and Rb phosphorylation.18,21 MIR34C is another tumor suppressor and induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis by downregulating candidate target genes, including MET, cyclin-dependent kinase 4, cyclin E2, and MYC.22,24 Finally, MIR137 targets CDK6, LSD1, and CDC42 to exert its tumor-suppressor function.16,46,47 Meanwhile, restoration of these endogenous miR-NAs through demethylation or their introduction in cells leads to down-regulation of target genes and inhibits cell proliferation and migration.24,48 In the current study, expression levels of all of these miRNAs were significantly downregulated in dysplasia or cancer compared with non-neoplastic UC mucosa, and showed a significantly inverse correlation between methylation and expression in MIR1, MIR124, and MIR137. Therefore, restoration of these miRNAs or inhibition of DNA methylation could be the basis of a strategy to slow or reverse age-related UC-associated neoplasia.

We acknowledge several potential limitations to the present study. First, we focused on only aging- and cancer-associated miRNAs, and further studies including a broader, unbiased genome-wide analysis may potentially identify additional methylation loci to assess the risk for UC-CRC. Second, our study design did not demonstrate the predictive potential of these miRNA methylation biomarkers to predict the occurrence of metachronous UC-related neoplasia. Finally, although we successfully validated our novel findings using an external independent cohort, the samples size of our study was still somewhat small. In addition, the clinical materials analyzed in this study were solely from patients of Japanese origin; however, considering the rarity of disease occurrence of UC-CRC, this is still perhaps one of the largest cohorts ever published in this context. Furthermore, because we successfully validated our markers in both fresh frozen and paraffin tissues, our data suggest that a screening test based on miRNA-methylation could be easily implemented on various types of clinical specimens in the clinic. Nonetheless, larger prospective trials including diverse ethnic populations with a consistent sampling protocol may be needed to further confirm the validity of these biomarkers and assess their predictive potential for identifying UC patients with high risk of developing UC-CRC, and preventing morbidity and mortality from this chronic disease.

In conclusion, age- and cancer-dependent methylation of mRNAs from a single rectal biopsy specimen has robust potential in permitting the identification of UC patients harboring dysplasia or cancer elsewhere in the colorectum.

Supplementary Material

EDITOR’S NOTES.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

Currently, we lack availability of robust biomarkers that can facilitate improved surveillance and identification of patients that are at high risk for developing ulcerative colitis associated colorectal cancer (UC-CRC).

NEW FINDINGS

Methylation of specific miRNAs occurred in an age- and cancer-dependent manner in UC patients. MiRNA methylation in non-neoplastic rectal mucosa successfully discriminated patients with UC-CRC from those without in two independent patient cohorts.

LIMITATIONS

The study was retrospective and we analyzed the methylation status of a panel of miRNAs using moderate sized clinical cohorts. Future, prospective studies using larger patient cohorts are needed.

IMPACT

Methylation status of a panel of miRNAs from a single rectal biopsy specimen may serve as important biomarkers for improving surveillance efficiency for patients at greatest risk for developing UC-CRC.

Acknowledgments

Ajay Goel had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors thank Yuki Orito for providing excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants R01 CA72851, CA181572, CA184792, CA202797, and U01 CA187956 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Health, a grant from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT; RP140784), pilot grants from the Baylor Sammons Cancer Center and Foundation, as well as funds from the Baylor Research Institute. Yuji Toiyama was supported in part by a Grant in Aid for Scientific Research (26462011) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan. Yoshinaga Okugawa, was supported by fellowship of the Uehara Memorial Foundation in Tokyo, Japan.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AUC

area under the ROC curve

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- FFPE

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- NPV

negative predictive value

- PPV

positive predictive value

- ROC

received operating characteristic

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- UC

ulcerative colitis

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the Digestive Disease Week, Chicago, IL, May 3–6, 2014.

Conflict of interests

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.037.

References

- 1.Hata K, Watanabe T, Kazama S, et al. Earlier surveillance colonoscopy programme improves survival in patients with ulcerative colitis associated colorectal cancer: results of a 23-year surveillance programme in the Japanese population. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1232–1236. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults (update): American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1371–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujii S, Fujimori T, Chiba T, et al. Efficacy of surveillance and molecular markers for detection of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal neoplasia. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1117–1125. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issa JP. Aging, DNA methylation and cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1999;32:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(99)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713–1725. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1102942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Issa JP, Ahuja N, Toyota M, et al. Accelerated age-related CpG island methylation in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3573–3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Risques RA, Lai LA, Brentnall TA, et al. Ulcerative colitis is a disease of accelerated colon aging: evidence from telomere attrition and DNA damage. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:410–418. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Issa JP, Ottaviano YL, Celano P, et al. Methylation of the oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nat Genet. 1994;7:536–540. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujii S, Tominaga K, Kitajima K, et al. Methylation of the oestrogen receptor gene in non-neoplastic epithelium as a marker of colorectal neoplasia risk in longstanding and extensive ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54:1287–1292. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.062059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tominaga K, Fujii S, Mukawa K, et al. Prediction of colorectal neoplasia by quantitative methylation analysis of estrogen receptor gene in nonneoplastic epithelium from patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8880–8885. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen WS, Leung CM, Pan HW, et al. Silencing of miR-1-1 and miR-133a-2 cluster expression by DNA hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1069–1076. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harada T, Yamamoto E, Yamano HO, et al. Analysis of DNA methylation in bowel lavage fluid for detection of colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:1002–1010. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueda Y, Ando T, Nanjo S, et al. DNA methylation of microRNA-124a is a potential risk marker of colitis-associated cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2444–2451. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng G, Kakar S, Kim YS. MicroRNA-124a and microRNA-34b/c are frequently methylated in all histological types of colorectal cancer and polyps, and in the adjacent normal mucosa. Oncol Lett. 2011;2:175–180. doi: 10.3892/ol.2010.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balaguer F, Link A, Lozano JJ, et al. Epigenetic silencing of miR-137 is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6609–6618. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki H, Takatsuka S, Akashi H, et al. Genome-wide profiling of chromatin signatures reveals epigenetic regulation of MicroRNA genes in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5646–5658. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lujambio A, Ropero S, Ballestar E, et al. Genetic unmasking of an epigenetically silenced microRNA in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1424–1429. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitano K, Watanabe K, Emoto N, et al. CpG island methylation of microRNAs is associated with tumor size and recurrence of non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:2126–2131. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu T, Liu K, Wu Y, et al. MicroRNA-9 inhibits the proliferation of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by suppressing expression of CXCR4 via the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2014;33:5017–5027. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agirre X, Vilas-Zornoza A, Jimenez-Velasco A, et al. Epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor microRNA Hsa-miR-124a regulates CDK6 expression and confers a poor prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4443–4453. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lujambio A, Calin GA, Villanueva A, et al. A microRNA DNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13556–13561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803055105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudson RS, Yi M, Esposito D, et al. MicroRNA-1 is a candidate tumor suppressor and prognostic marker in human prostate cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3689–3703. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toyota M, Suzuki H, Sasaki Y, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-34b/c and B-cell translocation gene 4 is associated with CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4123–4132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hur K, Toiyama Y, Takahashi M, et al. MicroRNA-200c modulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in human colorectal cancer metastasis. Gut. 2013;62:1315–1326. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toiyama Y, Takahashi M, Hur K, et al. Serum miR-21 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:849–859. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Link A, Balaguer F, Shen Y, et al. Fecal MicroRNAs as novel biomarkers for colon cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1766–1774. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang KH, Mestdagh P, Vandesompele J, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling to identify and validate reference genes for relative quantification in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hur K, Toiyama Y, Schetter AJ, et al. Identification of a metastasis-specific MicroRNA signature in human colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015:107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okugawa Y, Toiyama Y, Toden S, et al. Clinical significance of SNORA42 as an oncogene and a prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017;66:107–117. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hur K, Toiyama Y, Okugawa Y, et al. Circulating microRNA-203 predicts prognosis and metastasis in human colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017;66:654–665. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearce J, Ferrier S. Evaluating the predictive performance of habitat models developed using logistic regression. Ecological Modelling. 2000;133:225–245. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elith J, Leathwick J. Predicting species distributions from museum and herbarium records using multi-response models fitted with multivariate adaptive regression splines. Diversity and Distributions. 2007;13:265–275. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Josse C, Bouznad N, Geurts P, et al. Identification of a microRNA landscape targeting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in inflammation-induced colorectal carcino-genesis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G229–G243. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00484.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan YG, Zhang YF, Guo CJ, et al. Screening of differentially vexpressed microRNA in ulcerative colitis related colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2013;6:972–976. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanaan Z, Rai SN, Eichenberger MR, et al. Differential microRNA expression tracks neoplastic progression in inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:551–560. doi: 10.1002/humu.22021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranjha R, Aggarwal S, Bopanna S, et al. Site-specific microRNA expression may lead to different subtypes in ulcerative colitis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colo-rectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526–535. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe T, Ajioka Y, Mitsuyama K, et al. Comparison of TARGETED vs random biopsies for surveillance of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Gastro-enterology. 2016;151:1122–1130. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nohata N, Hanazawa T, Enokida H, et al. microRNA-1/ 133a and microRNA-206/133b clusters: dysregulation and functional roles in human cancers. Oncotarget. 2012;3:9–21. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nasser MW, Datta J, Nuovo G, et al. Down-regulation of micro-RNA-1 (miR-1) in lung cancer. Suppression of tumorignic property of lung cancer cells and their sensitization to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis by miR-1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33394–33405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Datta J, Kutay H, Nasser MW, et al. Methylation mediated silencing of MicroRNA-1 gene and its role in hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5049–5058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43.Yan D, da Dong XE, Chen X, et al. MicroRNA-1/206 targets c-Met and inhibits rhabdomyosarcoma development. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29596–29604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bazzoni F, Rossato M, Fabbri M, et al. Induction and regulatory function of miR-9 in human monocytes and neutrophils exposed to proinflammatory signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5282–5287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810909106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng L, Qi T, Yang D, et al. microRNA-9 suppresses the proliferation, invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer cells through targeting cyclin D1 and Ets1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kozaki K, Imoto I, Mogi S, et al. Exploration of tumor-suppressive microRNAs silenced by DNA hypermethylation inoral cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2094–2105. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu M, Lang N, Qiu M, et al. miR-137 targets Cdc42 expression, induces cell cycle G1 arrest and inhibits invasion in colorectal cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1269–1279. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilting SM, van Boerdonk RA, Henken FE, et al. Methylation-mediated silencing and tumour suppressive function of hsa-miR-124 in cervical cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:167. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.