Abstract

Aim

There is limited evidence on what behavioral economics strategies are effective and can be used to inform non-communicable diseases (NCDs) public health policies designed to reduce overeating, excessive drinking, smoking, and physical inactivity. The aim of the review is to examine the evidence on the use and effectiveness of behavioral economics insights on reducing NCDs lifestyle risk factors.

Methods

Medline, Embase, PhycINFO, and EconLit were searched for studies published between Jan 2002 and July 2016 and reporting empirical, non-pharmacological, interventional research focusing on reducing at least one NCDs lifestyle risk factor by employing a behavioral economics perspective.

Results

We included 117 studies in the review; 67 studies had a low risk of bias and were classified as strong or very strong, 37 were moderate, and 13 were week. We grouped studies by NCDs risk factors and conducted a narrative synthesis. The most frequent behavioral economics concepts were use of incentives, framing, and choice architecture. We found mixed results for effectiveness of behavioral economics insights on reducing NCDs lifestyle risk factors.

Conclusions

Most studies targeting tobacco consumption, physical activity levels, and eating behaviors from a behavioral economics perspective had promising results with potential impact on NCDs health policies. We recommend future studies to be implemented in real-life settings and on large samples from diverse populations.

Keywords: behavioral economics, non-communicable diseases, lifestyle risk factors

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) result from a combination of biological and lifestyle factors such as tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and overeating (1), and are the major cause of disability and death worldwide (2). In order to curb the current NCDs epidemic, it was proposed for interventions to target the automatic bases of behaviors rather than to encourage conscious reflection upon the (unhealthy) behavior (3). Similarly, behavioral economists capitalize on the psychological underpinnings of the human behavior to predict the decision-making process of individuals and, ultimately, positively influence their behavior without restricting freedom of choice (4).

In the last decade there was considerable and continuously growing research and public policy interest in behavioral economics, with multiple applications being focused on reducing the four major risk behaviors of NCDs (5–7). Yet, our search shows the existence of only five systematic reviews on behavioral economics-related concepts, three focusing on choice architecture interventions (8–10) and two focusing on time discounting (11,12). From a public policy perspective, interest for behavioral economics started to rise in the early 2000’s, when the libertarian paternalism approach to public policy has emerged (13,14).

The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate evidence for the application of behavioral economics strategies to reduce NCDs lifestyle risk factors. The specific objectives of the review are: i) to identify effective behavioral economics strategies used to promote tobacco cessation, reduce alcohol consumption, promote healthful diet, and increase physical activity; and ii) assess the extent to which the effective behavioral economics strategies could be used to inform NCDs public health policies.

Methods

This review is grounded in a structured systematic review protocol developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (15,16).

Data/information sources

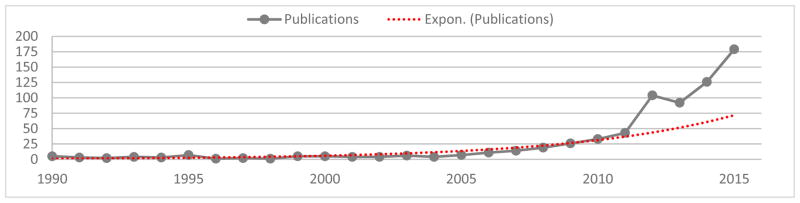

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and EconLit between January 1st 2002 (the year in which Daniel Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics and the start of the exponential growth in behavioral economics-related publications - see Figure 1 (17)) and July 1st 2016.

Figure 1.

Medline trend: automated yearly statistics of PubMed results for “behavioral economics” query (17)

Search strategy

The search strategy consisted of a combination of key words, Medical Subject Headings, and Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms. We combined six search themes using Boolean operators (see Table 1), and searched databases using individualized search strategies (refer to Appendix 1).

Table 1.

List of search themes and terms used for the searching strategies

| Search themes | Search terms |

|---|---|

| (i) Behavioral economics (18) | behavioral economics, anchoring, choice architecture, confirmation bias, default, framing, intertemporal choice, incentive, loss aversion, mental accounting, nudge, partitioning, social norm, social proof, status quo bias, time discounting |

| (ii) Study design | allocated, assigned, clinical trial, comparative studies, controlled, controlled clinical trial, cross-over studies, experiment, intervention, placebo, pre-post, randomization randomized controlled trial, RCT |

| (iii) Tobacco use | cessation, smoking, tobacco use, nicotine |

| (iv) Lack of physical activity | active, energy expenditure, exercise, exercise behavior, fundamental movement skill, motor activity, motor skill, movement, physical activity, physical exertion, physical fitness, sedentary, sport, training |

| (v) Poor nutrition | beverages, carbonated beverages, diet, dietary behavior, eating feeding behavior, food, nutrition, soda, soft drink, sugar intake, sweetened beverage, carbonated beverage, unhealthy diet |

| (vi) Alcohol consumption | alcohol use, alcohol abuse, alcoholic beverage, alcoholism, binge drinking, drinking, ethanol, liquors |

Eligibility criteria

We included studies published in English between January 2002 and July 2016, describing empirical, non-pharmacological research conducted on humans, focusing on reducing one of the four lifestyle risk factors of NCDs, depicting any type of intervention design (19) employed to support behavioral change, and reporting the use of at least one behavioral economics concept. We excluded studies published in abstract or studies for which we could not retrieve their full.

Data management

Documents were handled using the Mendeley Desktop reference manager software (20) and the Rayyan software for conducting systematic reviews (21).

Study selection

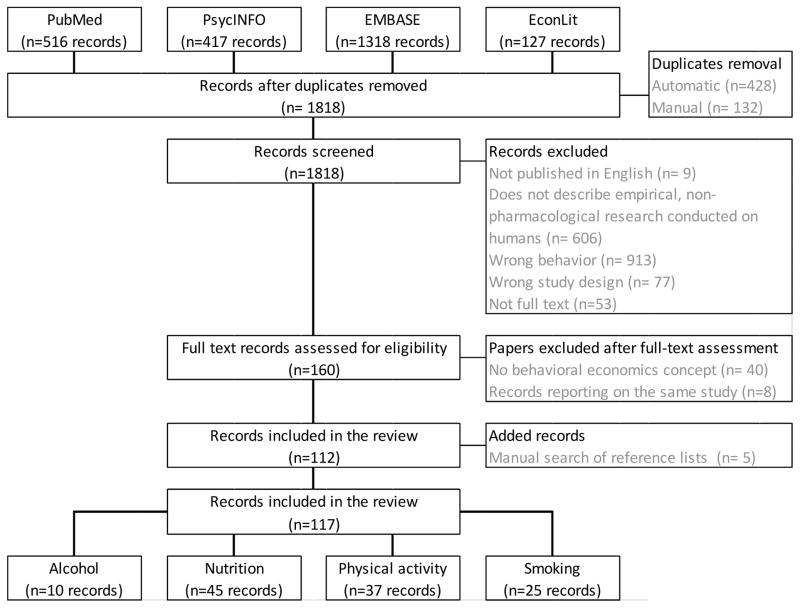

Studies were selected for inclusion by two independent reviewers, the inter-rater reliability (κ=.759, 95% CI; 96% percent agreement among raters) suggesting substantial agreement between reviewers (22). We resolved disagreements through discussion. Figure 2 describes the study selection procedure.

Figure 2.

Review flowchart

Data items, data extraction process, and synthesis

Variables for which data was extracted for each eligible study (see Appendix 2 to review the data extraction form) include: (i) general details (i.e. title, authors, year of publication); (ii) specific details (i.e. study purpose, NCDs risk factor researched, study participants; and (iii) outcomes (i.e. standardized measures assessing the lifestyle risk factors of NCDs; changes in attitudes, beliefs, and social norms; findings’ potential to inform public health policies).

We grouped studies included in the review based on the NCDs risk factor they focused on and the behavioral economics principle they employ. We used narrative synthesis was used for this review (23), as it was previously used for other systematic reviews on health behaviors (9,24,25).

Quality of studies included in the review

The quality of studies included in the review was assessed using Symour’s et al. methodological quality rating system (26) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Methodological quality system employed to assess quality of studies included in the review

| Rating | Definition | Study description | Design and methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| * | Weak | Many details missing (three or more of the following: setting, intervention design, duration, intensity, population, or statistical analysis), irrelevant design or methods. | Methodologic flaws (in statistical methods used, design of intervention, etc.). |

| ** | Moderate | Some details missing (one or two). | Small sample size (<50) or short duration (<1 month). |

| *** | Strong | Some details missing (one or two). | Larger sample size (≥50) and longer duration (>1 month). |

| **** | Very strong | Very clear, all details provided. | Larger sample size (≥50), longer duration (>1 month), and all of the following criteria: population randomly allocated or matched for intervention or control, generalizable results, or validated assessment. |

Note: Instrument reproduced from Seymour et al. (2004)

Results

From the 2378 searches, 112 unduplicated records met the inclusion criteria. After searching the reference lists of included articles, we included 5 additional records in our review, rendering a total of 117 articles (refer to Table 3 for the full list of articles included in the review).

Table 3.

Quality assessment of studies included in the review

| Weak | Moderate | Strong | Very strong | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| NCDs risk factor | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n |

| Alcohol | 4 | 40 | 6 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Nutrition | 4 | 8.88 | 14 | 31.11 | 15 | 33.33 | 12 | 26.66 | 45 |

| Physical activity | 4 | 10.81 | 10 | 27.03 | 11 | 29.73 | 12 | 32.43 | 37 |

| Smoking | 1 | 4 | 7 | 28 | 8 | 32 | 9 | 36 | 25 |

| Total | 13 | 11.11 | 37 | 31.62 | 34 | 29.06 | 33 | 28.20 | 117 |

From the included studies, 18 were implemented in laboratory settings. The most frequent behavioral economics concept in these studies was use of monetary and nonmonetary incentives (n=51), followed by framing (n=28), and by choice architecture (n=12). The intervention duration ranged from 5 minutes to 3 years. The number of participants ranged from 7 to 304,054.

Study quality assessment

Most of the studies included in this review were of an experimental nature. Thus, they entailed small sample sizes and short duration. Studies focusing on alcohol abuse were of the poorest methodological quality. In this review, studies targeting the eating behavior of the individuals were found to be less affected by methodological biases.

Studies focusing on reducing alcohol consumption

The 10 studies targeting alcohol consumption included a total of 2528 subjects, with sample sizes ranging from 13 (27) to 660 (28) subjects. Studies were implemented in laboratories of large universities in the USA (27–30), classrooms (31–33), fraternity houses (34), and online environments through email (35) and Facebook (36). All the studies focused on college students, with most targeting heavy drinkers (27,29,33,35), and were based on convenience samples. Seven studies included randomization of participants (29–33,35,36) and four reported using a control group (29,32,33,36). For articles which reported intervention durations, this ranged from 30 minutes (33) to 8 hours (34). For six studies, intervention duration was not reported (28,30–32,35,36).

In terms of employed behavioral economics concepts, four studies focused on changing social and group-specific norms associated with alcohol consumption (28,32,35,36), three on delayed discounting by emphasizing the role of drinking on career goals or constructive alternatives to drinking (27,29,33), one on the prospect theory by testing the effects of loss and gain frames on reported binge drinking (31), one on academic constraints associated with alcohol consumption (30), and one on the use of monetary incentives to prevent excessive alcohol consumption (34). Most studies focused on changes in social norms and self-reported alcohol consumption, and only one study reported biochemical assessment of alcohol consumption (blood alcohol concentration) (34).

Concerning the policy potential of these findings, two studies propose changes in campus policies by (i) increasing availability of self-evaluation of blood alcohol concentrations as a means to promote lower intoxication levels (34), and (ii) manipulation of class schedules as a means to reduce alcohol use in the night prior to early next-day classes (30).

Studies focusing on reducing tobacco use

Reduction in smoking was targeted in 25 interventional studies with a total of 12,278 participants, sample sizes ranging from 43 (37) to 2538 (38) participants. Among the identified articles, seven reported studies implemented in medical settings (39–45), six in educational settings (46–51), while four described online interventions (37,38,52,53). Others were implemented at home (54), in the workplace (55,56) or by telephone (57–59). Regarding participants, interventions focused on pregnant smokers (n=4) (40–42,45), adult smokers (n=5) (37,43,50,52,60), smokers seeking to quit (n=3) (57,58,61), college students (n=4) (47,48,51,53), adolescents (n=3) (46,49,54), employees (n=2) (38,55,56), or other participants categories (n=2) (44,59). Most studies were based on convenience sampling or purposive sapling. We identified randomized controlled trials (n=14) (38,39,41,43–46,49,54,56–58,60), experimental or quasi-experimental studies (n=7) (37,47,48,50–52,61), and pre-post evaluation or post-evaluation only studies (n=4) (40,53,55,59). Reported intervention durations ranged from 10 minutes (48) to 12 months (43).

The behavioral economics concept most frequently reported was incentives, either alone (n=11) (39–41,44,45,49,54,56,61,62) or in combination with other behavioral economics concepts (n=3) (38,55,60). Framing was used in eight studies (37,48,51–53,57–59), while two studies employed pledges (46) or use of priming (47).

The policy implications of three studies included in the review refer to the development of positively framed anti-smoking Public Service Announcements (PSAs) (48) for individuals who have low nicotine addiction, while negatively framed anti-smoking PSAs have the potential to be more effective for individuals who are aware that smoking is an unhealthy behavior and intend to change (53); at a population level, variation in terms of warning content was found to have sustained effectiveness (52). A study conducted in Thailand which used incentives combined with peer-pressure and a pre-commitment contract to reduce smoking suggested that team-based approaches are more cost-effective in poor communities (60), while the results of a study conducted in the UK suggest that spirometry and providing information about lung age to smokers has the potential to be cheaper and more effective than other available smoking cessation programs (43).

Studies focusing on improving nutrition

From the 117 articles included in the review, 45 articles focused on improving the eating behavior of a total sample of 40,528 individuals. Sample sizes ranged from 13 (63) to 8,000 (64) participants. Only 4 of the identified studies described interventions implemented in a laboratory setting (65–68), 12 were implemented in cafeterias or canteens (69–80), and 7 were implemented in schools (64,81–86). In terms of participants, 17 studies focused on primary or secondary school children (63,64,68–71,79,80,82–90), 8 focused on adults (67,81,91–96). Special populations targeted by these studies include overweight children (63) and obese women (91), postpartum women (95), adolescents and young adults with intellectual disabilities (97), adolescent girls at risk of obesity, and low-income individuals (88,98). All studies were based on convenience or purposive samples, with the exception of three studies which used a probabilistic (99), a clustered (85), and a stratified random (80) sampling design. Thirteen studies were randomized controlled studied (63,75,82,85–87,89,91,92,96,98,100,101), ten described field experiments (64,74,75,79,80,88,99,102–104), and two were quasi-experimental studies (71,97). Reported intervention durations ranged from 7 minutes (89) to 24 months (77).

Ten of these studies employed the concept of choice architecture (66,71,76–78,82,85,97,102,104) to make changes to serving lines (66,78,97), to vending machines (85), or to indicate healthful and unhealthful foods by using traffic lights-like labels (76,77). Incentives, both monetary and non-monetary, used alone or in combination with other behavioral economics concepts (99), were reported in 8 studies (65,75,90,95,98,100,105). Framing was used to influence the normative size of food portions (74), to negatively or positively frame the incentives received after selecting a healthful/unhealthful food item (88), and to emphasize healthier choices using a “tick” (92) or single-/dual-column nutritional labels (81). Other studies made use of defaults rules by encouraging the selection of at least one serving of fruits or vegetables for a meal (84), by using a bowl of the same size for every meal (91), and by pre-preparing vegetables in containers (87,101).

In term of findings with policy implications, the studies included in this review propose: the use of traffic-light labels as means to promote healthy food choices (76,77); the use of incentives in combination with education to decrease consumption and reduce waste (88); changes in serving lines as a means to influence choice of healthful foods (72,78,81,102); and making the healthier choice the easiest choice (97) and the unhealthy choice more difficult to get (70).

Studies focusing on increasing physical activity

We identified 37 articles describing 39 interventional studies focused on increasing physical activity. The sample sizes of these studies ranged from 7 (106) to 30,4054 (107), resulting in a total of 449,406 participants. Twelve studies were web- or mHealth-based (108–119), eight were implemented in educational settings (120–126), five were conducted in laboratory settings (106,127–130), while four were implemented in sports facilities (131–134). Other studies reported interventions conducted at the workplace (135–137), in medical centers (115,138), in a senior center (130), or outdoors (139). Participants were employees (n=7) (108,109,115–117,119,120,131,135–137), college students (n=8) (106,113,124,127,128,131,134) and school children (n=6) (114,121–123,133,139). Participants were further described as sedentary or overweight (115,116,126,128,138,140), older adults (115,127,129,130,141), or members in health programs (106,107,110–112,118). Regarding the selection of participants, 38 studies employed a convenience sampling design and one study (127) used snowball sampling. The articles included in the review describe randomized controlled designs (n=14) (112–117,119,126,132–134,138,139), experimental and quasi-experimental designs (n=14) (111,121,123,124,127,130,131,135–137,140,141), pre-post evaluation or post-evaluation only designs (n=9) (106,109,110,118,120,122,125,128,129), while two studies had an observational design (107,108). The intervention durations ranged from 5–7 minutes (111) to 3 years (107); three studies (112,113,129) did not mention the length of intervention.

The researchers used incentives in more than half of the studies (n=24), either alone (n=19) (106–110,115,116,119,121,122,124,125,131,134,135,137,139) or combined with other behavioral economics concepts (n=5) (114,117,126,136,140). Other employed behavioral economics concepts included framing (n=10) (111,113,118,123,127–130,138), anchoring (112,133), nudging (112,132), use of pre-commitments (112,141), default options (112) or disconnected values models (120).

Some studies suggest that using incentives could increase physical activity and subsequently minimize the health risks of sedentarism (106,107,116,122,131), but not among currently active individuals (124). On the other hand, commitment contracts or money deposits have the potential to be more scalable with minimal resources and could be similar or more cost-effective than offering monetary incentives from the interventionist’s part (112,141). The use of exergames – video games prompting the player to move – can promote physical activity among school-children (123). Older adults could benefit from programs including positively-framed messages and meant to improve their physical activity (130). Finally, nudging was also proposed as an effective way to increase physical activity by sending reminders about the targeted behavior or feedback regarding participants’ behaviors (132).

Discussions

The aim of this review was to evaluate evidence on the use and effectiveness of behavioral economics strategies to reduce lifestyle risk factors for the development of non-communicable diseases. Due to the heterogeneity of primary outcomes and the weak or moderate quality of included studies, we could not determine the effectiveness of interventions targeting NCDs risk factors and using behavioral economics underpinnings in this review. Therefore, this review should be seen as an indicator of the current research in this field and a starting point for future research to be conducted in this area.

The relatively poor quality of studies focusing on alcohol consumption and behavioral economics identified in this review calls for more non-laboratory-based, randomized controlled studies on this specific topic.

Our findings show that the behavioral economics concepts employed across the studies included in the review vary by the nature of the targeted NCDs risk behavior. More specifically, studies reporting interventions designed to reduce alcohol consumption employed concepts such as social norms and delayed discounting. On the other hand, interventional studies focusing on reducing smoking and those targeting an increase in physical activity levels were more likely to use incentives as part of their strategy to diminish tobacco use and/ or increase physical inactivity. The use of incentives was also frequent in nutrition-related studies, but a large proportion of these studies also employed choice architecture and framing strategies to increase fruit and vegetable intake or reduce consumption of unhealthful foods.

Offering incentives was the most common technique used to change the NCDs health risk behaviors we focused on in this review. The purpose of this review was not to focus on interventions using incentives provided contingent on smoking cessation, reduced alcohol intake, improved nutrition, or increased physical activity, as this has been the focus of previous reviews (142–147). The results of this review suggest a potentially more cost-effective alternative to the use of monetary and non-monetary incentives. Such a strategy could consist in asking participants to make pre-commitments, either by signing a contract to change a behavior (46,55,60,112,136,148) or by making a monetary deposit as a guarantee for behavioral change (141).

Our findings emphasize several behavioral economics strategies to reduce smoking, poor nutrition, and physical inactivity which warrant future research, due to their potential policy implications. In the case of tobacco use, we found that positively framed anti-smoking public service announcements may be more effective in the case of individuals with low nicotine addiction, whereas negatively framed anti-smoking public service announcements may be more effective in individuals who are in the contemplation phase (53). In addition, offering information to smokers regarding the age of their lungs could be an effective way to encourage them to stop using tobacco (43). Regarding potential policies designed to impact nutrition and eating behaviors, these could incorporate traffic-light labels (76,77) and changes in serving lines (72,78,81,102) as means to promote healthy food choices. To reduce physical inactivity, researchers recommend policy makers to implement programs with a commitment contract or money deposit component (112,141), focus on development of exergames (123), and nudge individuals by offering constant feedback regarding the status of their physical activity level (132).

Conclusions and future research

This review found inconclusive evidence regarding the success of behavioral economics strategies to reduce alcohol consumption, but suggests several strategies with policy-level implications which could be used to reduce smoking, improve nutrition, and increase physical activity. This review has highlighted some studies which showed potential to reduce smoking and overeating, and to increase physical activity. Yet, the majority of these studies have to be replicated over longer periods of time, and among more diverse populations, to demonstrate the generalizability of their findings. We also recommend future studies to compare their outcomes against those of established health promotion interventions designed to deter the lifestyle risk factors of NCDs, in order to establish if interventions grounded on behavioral economics concepts are more effective than other strategies to reduce overeating, smoking, excess drinking, and lack of physical activity.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this review include the existence of a systematic review protocol and the use of two reviewers for the selection of the relevant studies. Limitations consists in the use of only four electronic databases as data sources and the exclusion of articles published in non-English languages, possibly resulting in selection bias.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW008308. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None to declare

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Competing interest

None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO | Noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miranda JJ, Kinra S, Casas JP, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: context, determinants and health policy. Trop Med Int Health. 2008 Oct;13(10):1225–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marteau TM, Hollands GJ, Fletcher PC. Changing Human Behavior to Prevent Disease: The Importance of Targeting Automatic Processes. Science (80-) 2012;337(6101) doi: 10.1126/science.1226918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2014 Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. Rockville: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice T. The behavioral economics of health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health Annual Reviews. 2013 Jan;34:431–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajbhandari-Thapa J, Lyford C. Obes Rev J. Vol. 15. Rajbhandari-Thapa, Texas Tech University; United States: 2014. Can behavioral economics promote healthy food choice? A systematic review; p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, Glick HA, Puig A, Asch DA, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb;360(7):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollands GJ, Shemilt I, Marteau TM, Jebb SA, Kelly MP, Nakamura R, et al. Altering micro-environments to change population health behaviour: towards an evidence base for choice architecture interventions. BMC Public Health England. 2013;13:1218. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skov LR, Lourenço S, Hansen GL, Mikkelsen BE, Schofield C. Choice architecture as a means to change eating behaviour in self-service settings: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013 Mar;14(3):187–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thapa JR, Lyford CP. Int Food Agribus Manag Rev. A Vol. 17. International Food and Agribusiness Management Association (IFAMA); 2014. Behavioral Economics in the School Lunchroom: Can it Affect Food Supplier Decisions? A Systematic Review. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barlow P, McKee M, Reeves A, Galea G, Stuckler D. Int J Epidemiol. Oxford University Press; 2016. Nov, Time-discounting and tobacco smoking: a systematic review and network analysis; p. dyw233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlow P, Reeves A, McKee M, Galea G, Stuckler D. Unhealthy diets, obesity and time discounting: a systematic literature review and network analysis. Obes Rev. 2016 Sep;17(9):810–9. doi: 10.1111/obr.12431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camerer C, Issacharoff S, Lowenstein G, O’Donoghue T, Rabin M. Regulation for conservatives: Behavioral economics and the case of “asymetrical paternalism”. Univ PA Law Rev. 2003;151(3):1211–54. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thaler R, Sustein C. Libertarian Paternalism. Am Econ Rev. 2003;93(2):175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015 Jan;349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015 Jan;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corlan AD. Medline trend: automated yearly statistics of PubMed results for any query [Internet] 2004 Available from: http://dan.corlan.net/medline-trend.html.

- 18.Samson A. The Behavioral Economics Guide 2014. 2014 https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/BEGuide2014.pdf.

- 19.Thiese MS. Observational and interventional study design types; an overview. Biochem medica. 2014 Jan;24(2):199–210. doi: 10.11613/BM.2014.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendeley. Mendeley Desktop. London: Mendeley Ltd; 2011. Getting Started with Mendeley; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elmagarmid A, Fedorowicz Z, Hammady H, Ilyas I, Khabsa M, Ouzzani M. Rayyan: a systematic reviews web app for exploring and filtering searches for eligible studies for Cochrane Reviews. Evidence-Informed Public Health: Opportunities and Challenges Abstracts of the 22nd Cochrane Colloquium; Hyderabad, India. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem medica Croatian Society for Medical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 2012;22(3):276–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMahon S, Fleury J. External validity of physical activity interventions for community-dwelling older adults with fall risk: a quantitative systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs NIH Public Access. 2012 Oct;68(10):2140–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Everson-Hock ES, Johnson M, Jones R, Woods HB, Goyder E, Payne N, et al. Community-based dietary and physical activity interventions in low socioeconomic groups in the UK: a mixed methods systematic review. Prev Med (Baltim) 2013 May;56(5):265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seymour JD, Yaroch AL, Serdula M, Blanck HM, Khan LK. Impact of nutrition environmental interventions on point-of-purchase behavior in adults: a review. Prev Med (Baltim) 2004 Sep;39( Suppl 2):S108–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy JG, Skidmore JR, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Borsari B, Barnett NP, et al. Addict Res Theory. 6. Vol. 20. TELEPHONE HOUSE, 69-77 PAUL STREET, LONDON EC2A 4LQ, ENGLAND: INFORMA HEALTHCARE; 2012. A behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking; pp. 456–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Huchting KK, Neighbors C. Drug and Alcohol Review. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. A brief live interactive normative group intervention using wireless keypads to reduce drinking and alcohol consequences in college student athletes; pp. 40–7. LaBrie, Joseph W.: Department of Psychology, Loyola Marymount University, 1 LMU Drive, Suite 4700, Los Angeles, CA, US, 90045, jlabrie@lmu.edu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennhardt AA, Yurasek AM, Murphy JG. J Exp Anal Behav. 1. Vol. 103. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2015. Jan, Change in delay discounting and substance reward value following a brief alcohol and drug use intervention; pp. 125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gentile ND, Librizzi EH, Martinetti MP. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 5. Vol. 20. American Psychological Association; 2012. Academic constraints on alcohol consumption in college students: A behavioral economic analysis; pp. 390–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hutter RRC, Lawton R, Pals E, O’Connor DB, McEachan RRC. Tackling student binge drinking: Pairing incongruent messages and measures reduces alcohol consumption. Br J Health Psychol England. 2015 Sep;20(3):498–513. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy S, Moore G, Williams A, Moore L. An exploratory cluster randomised trial of a university halls of residence based social norms intervention in Wales, UK. BMC Public Health England. 2012;12:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yurasek AM, Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic intervention for alcohol and marijuana use. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol American Psychological Association. 2015;23(5):332–8. doi: 10.1037/pha0000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fournier AK, Ehrhart IJ, Glindemann KE, Geller ES. Intervening to decrease alcohol abuse at university parties: differential reinforcement of intoxication level. Behav Modif United States. 2004 Mar;28(2):167–81. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor MJ, Vlaev I, Maltby J, Brown GDA, Wood AM. Heal Psychol. 12. Vol. 34. 750 FIRST ST NE, WASHINGTON, DC 20002-4242 USA: AMER PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOC; 2015. Dec, Improving Social Norms Interventions: Rank-Framing Increases Excessive Alcohol Drinkers’ Information-Seeking; pp. 1200–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridout B, Campbell A. Using Facebook to deliver a social norm intervention to reduce problem drinking at university. Drug Alcohol Rev Australia. 2014 Nov;33(6):667–73. doi: 10.1111/dar.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham JA, Faulkner G, Selby P, Cordingley J. Addict Behav. 8. Vol. 31. THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD OX5 1GB, ENGLAND: PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD; 2006. Aug, Motivating smoking reductions by framing health information as safer smoking tips; pp. 1465–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halpern SD, French B, Small DS, Saulsgiver K, Harhay MO, Audrain-McGovern J, et al. Randomized trial of four financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2015 May;372(22):2108–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins ST, Washio Y, Lopez AA, Heil SH, Solomon LJ, Lynch ME, et al. Examining two different schedules of financial incentives for smoking cessation among pregnant women. Prev Med (Baltim) Elsevier Science. 2014 Nov;68:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ierfino D, Mantzari E, Hirst J, Jones T, Aveyard P, Marteau TM. Addiction. 4. Vol. 110. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2015. Apr, Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: a single-arm intervention study assessing cessation and gaming; pp. 680–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopez AA. Examining delay discounting and response to incentive-based smoking-cessation treatment among pregnant women. ProQuest Information & Learning. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopez AA, Skelly JM, Higgins ST. Nicotine Tob Res [Internet] 4. Vol. 17. Burlington, United States: Oxford University Press; 2014. Apr 1, Financial incentives for smoking cessation among depression-prone pregnant and newly postpartum women: Effects on smoking abstinence and depression ratings; pp. 455–62. S.T. Higgins, Vermont Center on Behavior and Health, University of Vermont, UHC Campus. [cited 2016 Jul 5] Available from: http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L604376019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parkes G, Greenhalgh T, Griffin M, Dent R. Effect on smoking quit rate of telling patients their lung age: the Step2quit randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008 Mar;336(7644):598–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39503.582396.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sigmon SC, Miller ME, Meyer AC, Saulsgiver K, Badger GJ, Heil SH, et al. Addiction. 5. Vol. 111. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2016. May, Financial incentives to promote extended smoking abstinence in opioid-maintained patients: a randomized trial; pp. 903–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tappin D, Bauld L, Purves D, Boyd K, Sinclair L, MacAskill S, et al. Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;350:h134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Sheyab N, Alomari M, Shah S, Gallagher R. Trop Med Int Heal. Vol. 20. N” Al-Sheyab, Jordan University of Science and Technology; Irbid, Jordan: 2015. “Class smoke-free” pledge impacts on nicotine dependence in male adolescents: A cluster randomized controlled trial; pp. 255–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris JL, Pierce M, Bargh JA. Tob Control. 4. Vol. 23. BMJ Publishing Group; 2014. Jul, Priming effect of antismoking PSAs on smoking behaviour: a pilot study; pp. 285–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jung WS, Villegas J. The effects of message framing, involvement, and nicotine dependence on anti-smoking public service announcements. Health Mark Q England. 2011;28(3):219–31. doi: 10.1080/07359683.2011.595641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krishnan-Sarin S, Cavallo DA, Cooney JL, Schepis TS, Kong G, Liss TB, et al. An exploratory randomized controlled trial of a novel high-school-based smoking cessation intervention for adolescent smokers using abstinence–contingent incentives and cognitive behavioral therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend Elsevier Science. 2013 Sep;132(1–2):346–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romanowich P, Lamb RJ. J Appl Behav Anal. 3. Vol. 43. P. Romanowich, University of Texas, Health Science Center; USA: 2010. Effects of escalating and descending schedules of incentives on cigarette smoking in smokers without plans to quit; pp. 357–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen L. Health Commun. 1. Vol. 25. 325 CHESTNUT STREET, STE 800, PHILADELPHIA, PA 19106 USA: LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOC INC-TAYLOR & FRANCIS; 2010. The Effect of Message Frame in Anti-Smoking Public Service Announcements on Cognitive Response and Attitude Toward Smoking; pp. 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mays D, Turner MM, Zhao X, Evans WD, Luta G, Tercyak KP. NICOTINE Tob Res. 7. Vol. 17. GREAT CLARENDON ST, OXFORD OX2 6DP, ENGLAND: OXFORD UNIV PRESS; 2015. Jul, Framing Pictorial Cigarette Warning Labels to Motivate Young Smokers to Quit; pp. 769–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moorman M, van den Putte B. Addict Behav. 10. Vol. 33. THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD OX5 1GB, ENGLAND: PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD; 2008. Oct, The influence of message framing, intention to quit smoking, and nicotine dependence on the persuasiveness of smoking cessation messages; pp. 1267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reynolds B, Harris M, Slone SA, Shelton BJ, Dallery J, Stoops W, et al. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 6. Vol. 23. 750 FIRST ST NE, WASHINGTON, DC 20002-4242 USA: AMER PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOC; 2015. Dec, A Feasibility Study of Home-Based Contingency Management With Adolescent Smokers of Rural Appalachia; pp. 486–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwang G-S, Jung H-S, Yi Y, Yoon C, Choi J-W. Asia Pac J Public Health [Internet] 1. Vol. 24. SAGE Publications; 2012. Jan, Smoking cessation intervention using stepwise exercise incentives for male workers in the workplace; pp. 82–90. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21159694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, Glick HA, Puig A, Asch DA, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2009 Feb 12;360(7):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19213683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fucito LM, Latimer AE, Carlin-Menter S, Salovey P, Cummings KM, Makuch RW, et al. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2–3. Vol. 114. ELSEVIER HOUSE, BROOKVALE PLAZA, EAST PARK SHANNON, CO, CLARE, 00000, IRELAND: ELSEVIER IRELAND LTD; 2011. Apr, Nicotine dependence as a moderator of a quitline-based message framing intervention; pp. 229–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Latimer-Cheung AE, Fucito LM, Carlin-Menter S, Rodriguez J, Raymond L, Salovey P, et al. How do perceptions about cessation outcomes moderate the effectiveness of a gain-framed smoking cessation telephone counseling intervention? J Health Commun. United States. 2012;17(9):1081–98. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.665420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szklo AS, Freire Coutinho ES. Addict Behav. 6. Vol. 35. THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD OX5 1GB, ENGLAND: PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD; 2010. Jun, The influence of smokers’ degree of dependence on the effectiveness of message framing for capturing smokers for a Quitline; pp. 620–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.White JS. A team-based behavioral economics experiment on smoking cessation. ProQuest Information & Learning. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamb RJ, Kirby KC, Morral AR, Galbicka G, Iguchi MY. Shaping smoking cessation in hard-to-treat smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol United States. 2010 Feb;78(1):62–71. doi: 10.1037/a0018323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lopez AA, Skelly JM, Higgins ST. NICOTINE. 4. Vol. 17. Tob Res GREAT CLARENDON ST, OXFORD OX2 6DP, ENGLAND: OXFORD UNIV PRESS; 2015. Apr, Financial Incentives for Smoking Cessation Among Depression-Prone Pregnant and Newly Postpartum Women: Effects on Smoking Abstinence and Depression Ratings; pp. 455–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Stein RI, Paluch RA, Kilanowski CK. The challenge of identifying behavioral alternatives to food: clinic and field studies. Ann Behav Med United States. 2005;30(3):201–9. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loewenstein G, Price J, Volpp K. J Health. Vol. 45. Econ PO BOX 211, 1000 AE AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS: ELSEVIER SCIENCE BV; 2016. Jan, Habit formation in children: Evidence from incentives for healthy eating; pp. 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dolan P, Galizzi MM, Navarro-Martinez D. Soc Sci Med. SI. Vol. 133. THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE, KIDLINGTON, OXFORD OX5 1GB, ENGLAND: PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD; 2015. May, Paying people to eat or not to eat? Carryover effects of monetary incentives on eating behaviour; pp. 153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kongsbak I, Skov LR, Nielsen BK, Ahlmann FK, Schaldemose H, Atkinson L, et al. Food Qual Prefer. Vol. 49. Elsevier Science; 2016. Apr, Increasing fruit and vegetable intake among male university students in an ad libitum buffet setting: A choice architectural nudge intervention; pp. 183–8. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robinson E, Harris E, Thomas J, Aveyard P, Higgs S. Reducing high calorie snack food in young adults: A role for social norms and health based messages. In: Robinson E, editor. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. University of Liverpool; Liverpool, United Kingdom: 2013. p. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salmon SJ, Fennis BM, De Ridder DTD, Adriaanse MA, De Vet E. Heal Psychol. 2. Vol. 33. S.J Salmon, Department of Marketing, University of Groningen, 9700 AV Groningen; Netherlands: 2014. Health on impulse: When low self-control promotes healthy food choices; pp. 103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ensaff H, Homer M, Sahota P, Braybrook D, Coan S, McLeod H. Nutrients. 6. Vol. 7. POSTFACH, CH-4005 BASEL, SWITZERLAND: MDPI AG; 2015. Jun, Food Choice Architecture: An Intervention in a Secondary School and its Impact on Students’ Plant-based Food Choices; pp. 4426–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goto K, Waite A, Wolff C, Chan K, Giovanni M. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. Oxford: 2013. Do environmental interventions impact elementary school students’ lunchtime milk selection? pp. 360–76. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hakim SM, Meissen G. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2, S. Vol. 24. JOURNALS PUBLISHING DIVISION, 2715 NORTH CHARLES ST, BALTIMORE, MD 21218-4363 USA: JOHNS HOPKINS UNIV PRESS; 2013. May, Increasing Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables in the School Cafeteria: The Influence of Active Choice; pp. 145–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hanks AS, Just DR, Smith LE, Wansink B. Healthy convenience: nudging students toward healthier choices in the lunchroom. J Public Health (Oxf) 2012 Aug;34(3):370–6. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jue JJS, Press MJ, McDonald D, Volpp KG, Asch DA, Mitra N, et al. The impact of price discounts and calorie messaging on beverage consumption: a multi-site field study. Prev Med (Baltim) 2012 Dec;55(6):629–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Just DR, Wansink B. Health Econ. 7. Vol. 23. 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA: WILEY-BLACKWELL; 2014. Jul, ONE MAN’S TALL IS ANOTHER MAN’S SMALL: HOW THE FRAMING OF PORTION SIZE INFLUENCES FOOD CHOICE; pp. 776–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thorndike AN, Riis J, Levy DE. Prev Med (Baltim) Vol. 86. A.N Thorndike; Boston, United States: 2016. Social norms and financial incentives to promote employees’ healthy food choices: A randomized controlled trial; pp. 12–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thorndike AN, Sonnenberg L, Riis J, Barraclough S, Levy DE. A 2-Phase Labeling and Choice Architecture Intervention to Improve Healthy Food and Beverage Choices. Am J Public Health. 2012 Mar;102(3):527–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thorndike AN, Riis J, Sonnenberg LM, Levy DE. Traffic-light labels and choice architecture: promoting healthy food choices. Am J Prev Med Netherlands. 2014 Feb;46(2):143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wansink B, Hanks AS. Slim by Design: Serving Healthy Foods First in Buffet Lines Improves Overall Meal Selection. In: Wansink B, Charles S, editors. PLoS One. 10. Vol. 8. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University; Ithaca, NY, United States: 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wansink B, Just DR, Hanks AS, Smith LE. Pre-Sliced Fruit in School Cafeterias. Am J Prev Med Elsevier Science. 2013 May;44(5):477–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Raju S, Rajagopal P, Gilbride TJ. Marketing Healthful Eating to Children: The Effectiveness of Incentives, Pledges, and Competitions. J Mark. 2010 May;74(3):93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Antonuk B, Block LG. The Effect of Single Serving Versus Entire Package Nutritional Information on Consumption Norms and Actual Consumption of a Snack Food. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38(6):365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cohen JFW, Richardson SA, Cluggish SA, Parker E, Catalano PJ, Rimm EB. JAMA Pediatr. 5. Vol. 169. J.F.W Cohen, Department of Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health; Boston, United States: 2015. Effects of choice architecture and chef-enhanced meals on the selection and consumption of healthier school foods a randomized clinical trial; pp. 431–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jones BA, Madden GJ, Wengreen HJ. The FIT Game: preliminary evaluation of a gamification approach to increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in school. Prev Med (Baltim) Elsevier Science. 2014 Nov;68:76–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Just D, Price J. Default options, incentives and food choices: evidence from elementary-school children. Public Health Nutr EDINBURGH BLDG, SHAFTESBURY RD, CB2 8RU CAMBRIDGE, ENGLAND: CAMBRIDGE UNIV PRESS. 2013 Dec;16(12):2281–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kocken PL, van Kesteren NMC, Buijs G, Snel J, Dusseldorp E. Students’ beliefs and behaviour regarding low-calorie beverages, sweets or snacks: are they affected by lessons on healthy food and by changes to school vending machines? Public Health Nutr. England. 2015 Jun;18(9):1545–53. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014002985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morrill BA, Madden GJ, Wengreen HJ, Fargo JD, Aguilar SS. A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Food Dudes Program: Tangible Rewards are More Effective Than Social Rewards for Increasing Short- and Long-Term Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016 Apr;116(4):618–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cravener TL, Schlechter H, Loeb KL, Radnitz C, Schwartz M, Zucker N, et al. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. New York: 2015. Feeding strategies derived from behavioral economics and psychology can increase vegetable intake in children as part of a home-based intervention: results of a pilot study; pp. 1798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.List JA, Samek AS. The behavioralist as nutritionist: Leveraging behavioral economics to improve child food choice and consumption. J Health Econ PO BOX 211, 1000 AE AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS: ELSEVIER SCIENCE BV. 2015 Jan;39:135–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sharps M, Robinson E. Appetite. Vol. 100. M Sharps, Institute of Psychology, Health and Society, Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Liverpool; Liverpool, United Kingdom: 2016. Encouraging children to eat more fruit and vegetables: Health vs descriptive social norm-based messages; pp. 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thompson D, Baranowski T, Cullen K, Watson K, Liu Y, Canada A, et al. Food, fun, and fitness internet program for girls: pilot evaluation of an e-Health youth obesity prevention program examining predictors of obesity. Prev Med (Baltim) United States. 2008 Nov;47(5):494–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ahn HJ, Han KA, Kwon HR, Min KW. The Small Rice Bowl-Based Meal Plan was Effective at Reducing Dietary Energy Intake, Body Weight, and Blood Glucose Levels in Korean Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Korean Diabetes J. 2010;34:340–9. doi: 10.4093/kdj.2010.34.6.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Borgmeier I, Westenhoefer J. Impact of different food label formats on healthiness evaluation and food choice of consumers: a randomized-controlled study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(184) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Freedman DA, Choi SK, Hurley T, Anadu E, Hébert JR. Prev Med (Baltim) 5. Vol. 56. D.A Freedman, University of South Carolina; Columbia, SC 29208, United States: 2013. A farmers’ market at a federally qualified health center improves fruit and vegetable intake among low-income diabetics; pp. 288–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gilliland J, Sadler R, Clark A, O’Connor C, Milczarek M, Doherty S. Biomed Res Int. 410 PARK AVENUE, 15TH FLOOR, #287 PMB, NEW YORK, NY 10022 USA: HINDAWI PUBLISHING CORPORATION; 2015. Using a Smartphone Application to Promote Healthy Dietary Behaviours and Local Food Consumption. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Herman DR, Harrison GG, Afifi AA, Jenks E. American Journal of Public Health. American Public Health Assn; 2008. Effect of a targeted subsidy on intake of fruits and vegetables among low-income women in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; pp. 98–105. Herman, Dena R.: Nutrilite, Division of Access Business Group, 5600 Beach Blvd, Buena Park, CA, US, 90621-2007, dherman@ucla.edu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kral TVE, Bannon AL, Moore RH. Effects of financial incentives for the purchase of healthy groceries on dietary intake and weight outcomes among older adults: A randomized pilot study. Appetite Elsevier Science. 2016 May;100:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hubbard KL, Bandini LG, Folta SC, Wansink B, Eliasziw M, Must A. Public Health Nutrition. Cambridge: 2015. Impact of a Smarter Lunchroom intervention on food selection and consumption among adolescents and young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in a residential school setting; pp. 361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weinstein E, Galindo RJ, Fried M, Rucker L, Davis NJ. Impact of a Focused Nutrition Educational Intervention Coupled With Improved Access to Fresh Produce on Purchasing Behavior and Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables in Overweight Patients With Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Educ Sage Publications. 2014 Jan;40(1):100–6. doi: 10.1177/0145721713508823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Klerman JA, Bartlett S, Wilde P, Olsho L. The Short-Run Impact of the Healthy Incentives Pilot Program on Fruit and Vegetable Intake. Am J Agric Econ JOURNALS DEPT, 2001 EVANS RD, CARY, NC 27513 USA: OXFORD UNIV PRESS INC. 2014 Oct;96(5):1372–82. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cawley J, Hanks AS, Just DR, Wansink B. Unlisted: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, NBER Working Papers. 2016. Incentivizing Nutritious Diets: A Field Experiment of Relative Price Changes and How They are Framed; p. 21929. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Morland TB, Synnestvedt M, Honeywell S, Yang F, Armstrong K, Guerra CE. J Gen Intern Med. Vol. 29. T.B Morland, Geisinger Medical Center; Danville, United States: 2014. Effect of financial incentive for colorectal cancer screening adherence on appropriateness of colonoscopy orders; p. S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hansen PG, Skov LR, Jespersen AM, Skov KL, Schmidt K. Apples versus brownies: A field experiment in rearranging conference snacking buffets to reduce short-term energy intake. J Foodserv Bus Res Routledge. 2016 Jan;19(1):122–30. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thunstrom L, Nordstrom J. The Impact of Meal Attributes and Nudging on Healthy Meal Consumption--Evidence from a Lunch Restaurant Field Experiment. Mod Econ HUI Research AB, Stockholm and U WY. 2013 Oct;4(10A):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 104.van Kleef E, van den Broek O, van Trijp HCM. Appl Psychol Heal Well-Being. 2. Vol. 7. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2015. Jul, Exploiting the Spur of the Moment to Enhance Healthy Consumption: Verbal Prompting to Increase Fruit Choices in a Self-Service Restaurant; pp. 149–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tilley F, Weaver RG, Beets MW, Turner-McGrievy G. Healthy eating in summer day camps: the Healthy Lunchbox Challenge. 2. Vol. 46. 360 PARK AVE SOUTH, NEW YORK, NY 10010-1710 USA: ELSEVIER SCIENCE INC; 2014. pp. 134–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Irons JG, Pope DA, Pierce AE, Van Patten RA, Jarvis BP, Andersen RE, et al. Behav Chang [Internet] 2. Vol. 30. Cambridge University Press; 2013. Jun 11, Contingency Management to Induce Exercise Among College Students; pp. 84–95. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0813483913000089. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Patel D, Lambert EV, da Silva R, Greyling M, Kolbe-Alexander T, Noach A, et al. Am J Heal Promot. 5. Vol. 25. PO Box 1897, 810 East 10th Street: Lawrence, KS 66044-8897; 2011. Participation in fitness-related activities of an incentive-based health promotion program and hospital costs: a retrospective longitudinal study; pp. 341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sepúlveda M-J, Lu C, Sill S, Young JM, Edington DW. An Observational Study of an Employer Intervention for Children’s Healthy Weight Behaviors. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Herman CW, Musich S, Lu C, Sill S, Young JM, Edington DW. Effectiveness of an Incentive-Based Online Physical Activity Intervention on Employee Health Status. J Occup Environ Med [Internet] 2006 Sep;48(9):889–95. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000232526.27103.71. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00043764-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Berg CJ, Stratton E, Giblin J, Esiashvili N, Mertens A. Psychooncology [Internet] 10. Vol. 23. NIH Public Access; 2014. Oct, Pilot results of an online intervention targeting health promoting behaviors among young adult cancer survivors; pp. 1196–9. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24639118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.de Bruijn G-J, Out K, Rhodes RE. Testing the effects of message framing, kernel state, and exercise guideline adherence on exercise intentions and resolve. Br J Health Psychol [Internet] 2014 Nov;19(4):871–85. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12086. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/bjhp.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Goldhaber-Fiebert J, Blumenkranz E, Garber A. Committing to Exercise: Contract Design for Virtuous Habit Formation [Internet] Cambridge, MA: 2010. Dec, [cited 2016 Oct 9]. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w16624.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gray JB, Harrington NG. J Health Commun [Internet] 3. Vol. 16. Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. Feb 28, Narrative and Framing: A Test of an Integrated Message Strategy in the Exercise Context; pp. 264–81. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10810730.2010.529490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Guthrie N, Bradlyn A, Thompson SK, Yen S, Haritatos J, Dillon F, et al. Development of an accelerometer-linked online intervention system to promote physical activity in adolescents. PloS oneONE. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kullgren JT, Harkins KA, Bellamy SL, Gonzales A, Tao Y, Zhu J, et al. Health Educ Behav [Internet] 1 Suppl. Vol. 41. SAGE Publications; 2014. Oct, A mixed-methods randomized controlled trial of financial incentives and peer networks to promote walking among older adults; pp. 43S–50S. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25274710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Patel MS, Asch DA, Rosin R, Small DS, Bellamy SL, Heuer J, et al. Ann Intern Med [Internet] 6. Vol. 164. American College of Physicians; 2016. Mar 15, Framing Financial Incentives to Increase Physical Activity Among Overweight and Obese Adults; p. 385. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://annals.org/article.aspx?doi=10.7326/M15-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Patel MS, Asch DA, Rosin R, Small DS, Bellamy SL, Eberbach K, et al. J Gen Intern Med [Internet] 7. Vol. 31. Springer US; 2016. Jul 14, Individual Versus Team-Based Financial Incentives to Increase Physical Activity: A Randomized, Controlled Trial; pp. 746–54. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11606-016-3627-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.van ‘t Riet J, Ruiter RAC, Werrij MQ, de Vries H. Health Educ Res [Internet] 2. Vol. 25. Oxford University Press; 2010. Apr, Investigating message-framing effects in the context of a tailored intervention promoting physical activity; pp. 343–54. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19841041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Patel MS, Volpp KG, Rosin R, Bellamy SL, Small DS, Fletcher MA, et al. Am J Health Promot [Internet] 6. Vol. 30. SAGE Publications; 2016. Jul, A Randomized Trial of Social Comparison Feedback and Financial Incentives to Increase Physical Activity; pp. 416–24. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27422252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Anshel MH, Kang M. Behav Med [Internet] 3. Vol. 33. Heldref; 2007. Sep, An Outcome-Based Action Study on Changes in Fitness, Blood Lipids, and Exercise Adherence, Using the Disconnected Values (Intervention) Model; pp. 85–100. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3200/BMED.33.3.85-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Brinker JS. Academic incentives impact on increasing seventh-graders physical activity during leisure time. ProQuest. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 122.Burguera B, Colom A, Piñero E, Yanez A, Caimari M, Tur J, et al. Obes Facts [Internet] 5. Vol. 4. Karger Publishers; 2011. ACTYBOSS: activity, behavioral therapy in young subjects--after-school intervention pilot project on obesity prevention; pp. 400–6. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22166761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lwin MO, Malik S. J Health Commun [Internet] 2. Vol. 19. Taylor & Francis Group; 2014. Feb 5, Can Exergames Impart Health Messages? Game Play, Framing, and Drivers of Physical Activity Among Children; pp. 136–51. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10810730.2013.798372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Charness G, Gneezy U. Econometrica [Internet] 3. Vol. 77. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2009. Incentives to Exercise; pp. 909–31. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.3982/ECTA7416. [Google Scholar]

- 125.DeVahl J, King R, Williamson JW. J Am Coll Heal [Internet] 6. Vol. 53. Heldref; 2005. May, Academic Incentives for Students Can Increase Participation in and Effectiveness of a Physical Activity Program; pp. 295–8. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3200/JACH.53.6.295-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Garcia D. Feasibility of a campaign intervention compared to a standard behavioral weight loss intervention in overweight and obese adults. 2013 [cited 2016 Oct 9]; Available from: http://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/16509365.pdf.

- 127.Berry TR, Carson V. Br J Health Psychol [Internet] 1. Vol. 15. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2010. Feb, Ease of imagination, message framing, and physical activity messages; pp. 197–211. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1348/135910709X447811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. Psychol Health [Internet] 7. Vol. 26. Routledge; 2011. Jul, When “fit” leads to fit, and when “fit” leads to fat: How message framing and intrinsic vs. extrinsic exercise outcomes interact in promoting physical activity; pp. 819–34. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08870446.2010.505983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Li K, Cheng S, Fung H. Effects of message framing on self-report and accelerometer-assessed physical activity across age and gender groups. J Sport Exerc [Internet] 2014 doi: 10.1123/jsep.2012-0278. [cited 2016 Oct 9]; Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kin-Kit_Li/publication/259016984_Effects_of_Message_Framing_on_Self-Report_and_Accelerometer-Assessed_Physical_Activity_Across_Age_and_Gender_Groups/links/00463531005722d9cb000000.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 130.Notthoff N, Carstensen LL. Psychol Aging [Internet] 2. Vol. 29. American Psychological Association; 2014. Positive messaging promotes walking in older adults; pp. 329–41. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/a0036748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Acland D, Levy MR. Manage Sci [Internet] 1. Vol. 61. INFORMS; 2015. Jan, Naiveté, Projection Bias, and Habit Formation in Gym Attendance; pp. 146–60. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.2014.2091. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Calzolari G, Nardotto M. Nudging with Information: A Randomized Field Experiment on Reminders and Feedback. SSRN Electron J [Internet] 2011 [cited 2016 Oct 9]; Available from: http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=1924901.

- 133.Lamb K, Eaves S, Hartshorn J. J Sports Sci [Internet] 2. Vol. 22. Taylor & Francis Ltd; 2004. Feb, The effect of experiential anchoring on the reproducibility of exercise regulation in adolescent children; pp. 159–65. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02640410310001641485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pope L, Harvey-Berino J. Burn and earn: A randomized controlled trial incentivizing exercise during fall semester for college first-year students. Prev Med (Baltim) 2013;56(3):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hunter RF, Tully MA, Davis M, Stevenson M, Kee F. Physical Activity Loyalty Cards for Behavior Change: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Royer H, Stehr M, Sydnor J. Incentives, Commitments, and Habit Formation in Exercise: Evidence from a Field Experiment with Workers at a Fortune-500 Company. Am Econ J Appl Econ [Internet] 2015 Jul;7(3):51–84. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/10.1257/app.20130327. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Schumacher JE, Utley J, Sutton L, Horton T, Hamer T, You Z, et al. Rehabil Psychol [Internet] 1. Vol. 58. American Psychological Association; 2013. Boosting workplace stair utilization: A study of incremental reinforcement; pp. 81–6. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/a0031764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mascola AJ, Yiaslas TA, Meir RL, McGee SM, Downing NL, Beaver KM, et al. Eat Weight Disord - Stud Anorexia, Bulim Obes [Internet] 2–3. Vol. 14. Springer International Publishing; 2009. Jun 18, Framing physical activity as a distinct and uniquely valuable behavior independent of weight management: A pilot randomized controlled trial for overweight and obese sedentary persons; pp. e148–52. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF03327814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Finkelstein EA, Tan Y-T, Malhotra R, Lee C-F, Goh S-S, Saw S-M. A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of an Incentive-Based Outdoor Physical Activity Program. J Pediatr. 2013;163(1):167–172. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Petry NM, Barry D, Pescatello L, White WB. A Low-Cost Reinforcement Procedure Improves Short-term Weight Loss Outcomes. The American Journal of Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Donlin Washington W, McMullen D, Devoto A. Transl Issues Psychol Sci [Internet] 2. Vol. 2. Educational Publishing Foundation; 2016. A matched deposit contract intervention to increase physical activity in underactive and sedentary adults; pp. 101–15. [cited 2016 Oct 9] Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/tps0000069. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Sutherland K, Christianson JB, Leatherman S. Impact of targeted financial incentives on personal health behavior: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2008 Dec;65(6 Suppl):36S–78S. doi: 10.1177/1077558708324235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Mozaffarian D, Afshin A, Benowitz NL, Bittner V, Daniels SR, Franch HA, et al. Circulation. 12. Vol. 126. 530 WALNUT ST, PHILADELPHIA, PA 19106-3621 USA: LIPPINCOTT WILLIAMS & WILKINS; 2012. Sep, Population Approaches to Improve Diet, Physical Activity, and Smoking Habits A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association; p. 1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Burns RJ, Donovan AS, Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Rothman AJ, Jeffery RW. A theoretically grounded systematic review of material incentives for weight loss: implications for interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2012 Dec;44(3):375–88. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wall J, Ni Mhurchu C, Blakely T, Rodgers A, Wilton J. Nutr Rev. 12. Vol. 64. C Ni Mhurchu, Clinical Trials Research Unit, University of Auckland, School of Population Health; Auckland 1001, New Zealand: 2006. Effectiveness of monetary incentives in modifying dietary behavior: A review of randomized, controlled trials; pp. 518–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Cahill K, Perera R. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 4. England: 2011. Competitions and incentives for smoking cessation; p. CD004307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Strohacker K, Galarraga O, Williams DM. The impact of incentives on exercise behavior: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Behav Med United States. 2014 Aug;48(1):92–9. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9577-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Raju S, Rajagopal P, Gilbride TJ. Marketing Healthful Eating to Children: The Effectiveness of Incentives, Pledges, and Competitions. J Mark [Internet] 2010 May;74(3):93–106. [cited 2016 Jul 5] Available from: http://journals.ama.org/doi/abs/10.1509/jmkg.74.3.93. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.