Abstract

Introduction:

Optimal asthma control is a major aim of childhood asthma management. This study aimed to determine factors associated with suboptimal asthma control at the pediatric chest clinic of a resource-poor center.

Methods:

Over a 12-month study period, children aged 2–14 years with physician-diagnosed asthma attending the pediatric chest clinic of the Wesley Guild Hospital (WGH), Ilesa, Nigeria were consecutively recruited. Asthma control was assessed using childhood asthma control questionnaire. Partly and uncontrolled asthma was recorded as a suboptimal control. Relevant history and examinations findings were compared between children with good and suboptimal asthma control. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine the predictors of suboptimal asthma control.

Results:

A total of 106 children participated in the study with male:female ratio of 1.5:1, and majority (83.0%) had mild intermittent asthma. Suboptimal asthma control was observed in 19 (17.9%) of the children. Household smoke exposure, low socioeconomic class, unknown triggers, concomitant allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and poor parental asthma knowledge, were significantly associated with suboptimal control (P < 0.05). Low socioeconomic class (odds ratio [OR] =6.231; 95% confidence interval [CI] =1.022–8.496; P = 0.005) and poor parental asthma knowledge (OR = 7.607; 95% CI = 1.011–10.481; P = 0.007) independently predict suboptimal control.

Conclusion:

Approximately, one in five asthmatic children attending the WGH pediatric chest clinic who participated in the study had suboptimal asthma control during the study. More comprehensive parental/child asthma education and provision of affordable asthma care services may help improve asthma control among the children.

Keywords: Childhood asthma, control, predictors, resource-poor center

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease that leads to reversible narrowing and constriction of the airway and tendency of the airway to over-react to stimuli.[1] Asthma in children often manifest with recurrent episodic cough, breathlessness, wheezing, and poor exercise tolerance.[1,2] Asthma is a leading cause of respiratory disorder globally with over 334 million people suffering from the disease and the global prevalence ranging widely from 1% to 18%.[1,2,3] In developing countries including Nigeria, evidence from epidemiological studies point to increasing prevalence of childhood asthma.[1,2,3] Falade et al.[4] in 2004, reported a prevalence of 7.6% among school-age children using International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Questionnaire in Ibadan South West Nigeria.

Childhood asthma is a common cause of school absenteeism, hospitalization, and emergency room visits, as well as poor parental/caregiver and child's quality of life and increased family and governmental spendings on health.[5,6,7] These morbidities and burden associated with childhood asthma coupled with the fact that over the past decades, there has been reported increase in the prevalence of asthma[1,2,3] make the proper management of childhood asthma and appropriate symptoms control a necessity.

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) of the National Institutes of Health prescribes meticulous evaluation of asthma control as a very important component in childhood asthma management.[8] According to NAEPP guidelines, asthma control is assessed by patient reports of daytime and nocturnal symptoms, activity limitations due to asthma, need for rescue medications, and measures of lung function.[8] A major goal of asthma management is to achieve well-controlled asthma which had been associated with improved quality of life of children and their caregivers, fewer hospitalization and emergency room visit and increased productivity among children and their parents/caregivers.[5,6,7]

There have been lots of studies to assess the levels of asthma control in children and to determine factors influencing asthma control.[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] In the developed countries, the prevalence of poorly control asthma among children varies from 32% to 64%.[9,10,11,12] The factors predisposing to poorly controlled childhood asthma also vary widely.[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] Male sex, the use of woollen blanket, Surinamese ethnic group, and nondaily use of steroid were reported to predict poor childhood asthma control in a study in the Netherland.[12] Gandhi et al.[13] in Florida, however, reported that parental perceived self-efficacy with patient-physician interaction and satisfactions with shared decision-making were the determinants of children's asthma control status and asthma-specific health-related quality of life. Al-Muhsen et al.[14] in Saudi Arabia reported that poor education about asthma and/or medication use was the major determinant of poor childhood asthma control which was reported in 60.3% of the study population. Garba et al.[15] found that adherence to medications was associated with good asthma control observed in 55.7% of the children attending a tertiary health facility in Gauteng, South Africa.

There is paucity of reports about childhood asthma control from developing countries including Nigeria with the few studies on asthma control from Nigeria limited to few school age asthmatics.[16] Furthermore, factors influencing childhood asthma control may vary from one location to another as environmental, sociodemographic, and household variables which may affect asthma control differ. This study, therefore, aims to determine the prevalence and factors associated with suboptimal asthma control among children attending the Paediatric Chest Clinic of a Tertiary Centre in South West Nigeria.

Methods

Study design

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study.

Study location

This study was carried out at the pediatric chest clinic of the Wesley Guild Hospital (WGH), Ilesa, Nigeria over a 12-month period (January to December 2015). The clinic is run once a week by a team of clinicians including a pediatric pulmonologist assisted by resident doctors and other staff. Ten to 15 children with infectious and noninfectious respiratory conditions are attended to per week. Childhood asthma accounts for about 3.5% of an average of 3300 children seen annually at the pediatric inpatient and outpatient departments of the hospital.

The WGH is a Tertiary Annexe of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex (OAUTHC), Ile-Ife. The hospital is one of the main referral centers providing general and specialized pediatric care for the people of Osun and few neighboring states. Ilesa, where the hospital is located is the largest town in Ijesaland, situated on latitude 7°35´ N and longitude 4°51´E and is about 200 km North-East of Lagos.[17]

Study population

All children aged 2–14 years with physician-diagnosed asthma[1] and/or history of recurrent episodes of cough, wheezing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath which resolves spontaneously or with the use of bronchodilators were consecutively recruited. Informed consent and assent were obtained from the caregivers and older children, respectively. Other inclusion criteria for the study were having attended the chest clinic for a minimum of 3 months, and caregivers must have at least primary education with the ability to read and write. This will enable the caregivers answer the questions of the research tools including the Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (AKQ) without having to translate the questions to the local languages.

Sociodemographic information obtained from the patients and or the caregiver included age, sex, and age at diagnosis of asthma in the child. A history of asthma in the parents or close relatives of the children was also obtained. Family and personal history of other allergic conditions such as allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and dermatitis were also obtained. History about previous asthma-related hospitalization and possible triggering factors of acute asthma exacerbation was also obtained. Also of interest in this study is the gestational age at delivery of the children and whether they were exclusively breastfed or not. Number of individuals sharing the same room as the child and overcrowding for this study was defined as having three or more persons sharing the same room as the child.[18] Information about the presence of pets, tobacco smokers/users in the household and source of fuel for household cooking was also obtained.

The severity of asthma among the children was assessed using Global Initiative for Asthma criteria and categorized into mild intermittent as well as mild, moderate, and severe persistent asthma.[2] The caregivers were asked about the frequency of daytime symptoms, nighttime sleep disturbance from symptoms of asthma, days with the limitation of activities due to asthma during the past month.[2] Parental socioeconomic class was determined using the method described by Oyedeji.[19] This is based on rank assessment of the occupations and highest educational qualification of both parents. Professionals with postsecondary education were ranked as upper class, while unskilled laborers or petty traders with primary education were ranked as lower social class.[19]

The level of asthma control for the study participants was assessed according to NAEPP guidelines.[8] Children with at least one nocturnal asthma symptoms, 2 or more daytime symptoms within a month, use of rescue medication for at least twice per week and any form of limitation of normal activities as a result of asthma symptoms were classified as having suboptimal (partly and poorly) control. Children without the highlighted symptoms were classified as having well-controlled asthma.

Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire

The level of caregivers' asthma knowledge for this study was assessed using a 25-item knowledge questionnaire about childhood asthma.[20] The validated questionnaire has an adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha of 0.69). The AKQ was administered to the caregiver-patient pair by the authors. The minimum and maximum score of the AKQ is 0 and 25, respectively. Any score <11 was regarded as inadequate (poor) knowledge about childhood asthma.[20]

The study participants were examined for comorbid conditions such as allergic dermatitis, conjunctivitis, and rhinitis. For this study, allergic dermatitis was defined using the diagnostic criteria of Williams et al.[21] This was based on the presence of pruritic vesicular, weeping or crusting eruptions. These lesions may also be dry, scaly, and lichenified found mostly in large joint flexures.[21] The children were then referred to a dermatologist for confirmation. Allergic rhinitis was defined using Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma criteria.[22] This is based on the presence of recurrent nasal itching, discharge, sneezing, and nasal obstruction induced by exposure to allergens.[22] Children with eye symptoms were referred to the ophthalmologist for the diagnosis and management of associated allergic conjunctivitis.

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the OAUTHC, Ile-Ife with Protocol Number ERC/2015/02/12.

Data analysis

This was done using Statistical Programme for Social Sciences (SPSS) Software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, 2008). Categorical variables such as sex, severity of asthma, and asthma control were summarized using proportions and percentages, while continuous variables like age of the children and caregivers, duration since asthma was diagnosed and level of caregivers' knowledge about childhood asthma were summarized using means and standard deviations (SDs) for normally distributed variables and median and interquartile ranges for nonnormally distributed ones. Differences between continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t-test, while categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson's Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test as appropriate (with Yate's correction where applicable). The level of significance at 95% confidence interval (CI) was taken at P < 0.05. Association between dependent (suboptimal asthma control) and independent variables (study variables) that gave significant results in the univariate analysis was assessed using binary logistic regression analysis to adjust for possible confounders and determine the predictors of suboptimal control among the children with asthma. Results were interpreted with odds ratio (OR) risk and 95% CI at P < 0.05.

Results

Over a 12-month period (January to December 2015), 130 children with asthma were seen in the pediatric chest clinic of the WGH, Ilesa. Twenty-four (18.5%) of the children were excluded from this study. This included 11 (8.5%) children who were <2 years of age and 3 (2.3%) children who had not attended the clinic for 3 consecutive months before the end of the study.

A total of 106 children with asthma who met the inclusion criteria of this study were recruited and form the basis of further analysis. Eighty-seven (82.1%) of the 106 children had well-controlled asthma, while asthma was partly controlled in 11 (10.4%) and uncontrolled in 8 (7.5%) of the children. Therefore, 19 (17.9%) of the children had suboptimal asthma control.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the children with asthma

Sex and age distribution of the children

Of the 106 children with asthma 64 (60.4%) were males, with a male:female ratio of 1.5:1. The ages of the children ranged from 2 to 14 years with a mean (SD) age of 6.4 (3.9) years. Fifty-five (51.9%) of the children were 6 years and above [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and general information of the children and caregivers/parents as related to asthma control

Parental socioeconomic class

Majority (45.3%) of the children were from upper social class, with only 12 (11.3%) from low social class. Furthermore, 50 (48.4%) of the caregivers of these children had postsecondary education and the predominant occupation of the caregivers was trading (47.2%) [Table 1].

Caregivers' knowledge about childhood asthma

Thirty-two (30.2%) of the caregivers had poor knowledge about childhood asthma, while 74 (69.8%) had good knowledge about childhood asthma based on their scores in the AKQ.

Other information about the children with asthma

About one-fifth (23 children) lived in overcrowded houses, and 42 (39.6%) of the children live with at least one pet in the house. These pets included dogs 25 (23.6%), cats 5 (4.7%), and further 12 (11.3%) rear poultry in the house. Majority (97.2%) of the children were born at term, but only 64 (60.4%) were exclusively breastfed for the first 4–6 month of life.

Co-morbid condition and asthma triggers in the children

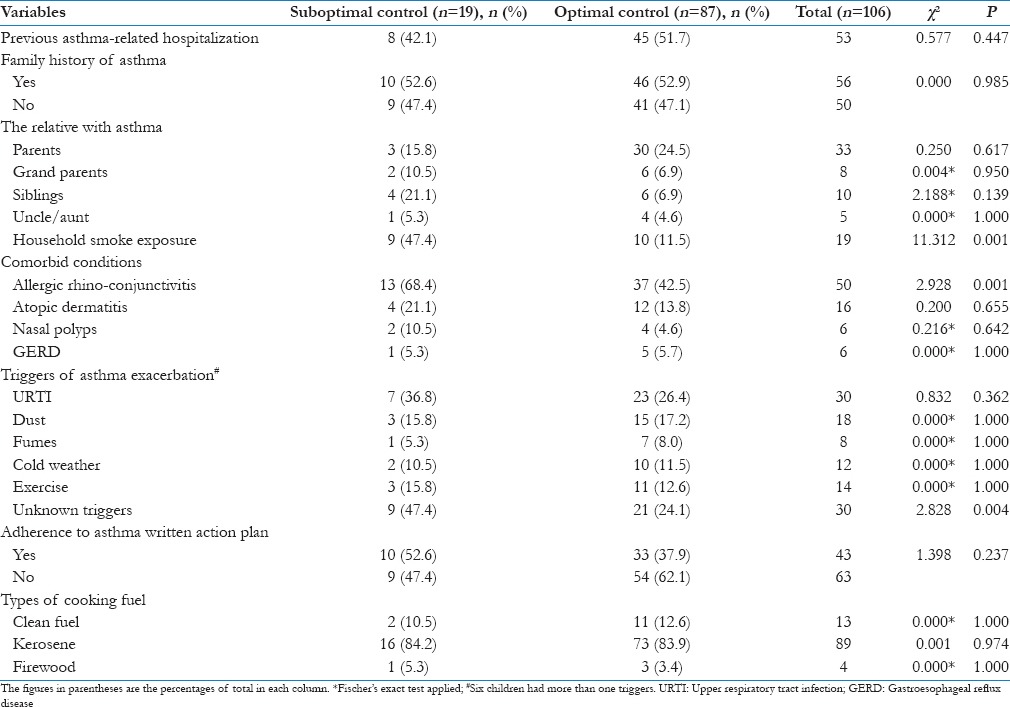

The predominant comorbid condition observed among the children was allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (47.2%). Others are highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comorbid conditions and triggers in the children as related to asthma control

Triggers of asthma exacerbations

Thirty (28.3%) of the children reported no known triggers of their asthma, while specific triggers were identified in 76 (71.7%) of them. The triggers of acute asthmatic exacerbations in the study participants are highlighted in Table 2.

Family history of asthma

History of asthma is present in close relative in 56 (52.8%) of the children. About one-third of the children had at least one parent who is a known asthmatic. The proportions of other relatives with asthma are shown in Table 2. No family history of asthma was reported in 50 (47.2%) of the children.

Previous asthma-related hospitalization

One-half of the children had been hospitalized for asthma exacerbation at least once in the past. Of these 53 children, 19 (17.9%) had been hospitalized two times or more in the past.

Type of household cooking fuel

Only 13 (12.3%) of the study participants used clean fuel (electric and gas cooker) for household cooking; the rest used unclean fuel for cooking. These included kerosene stove (84.0%) and firewood (3.8%). In addition, 19 (17.9%) of the children were exposed to cigarettes smoke as there was at least a smoker living in the household [Table 2].

Asthma severity in the children

Majority (83.0%) of the children had mild intermittent asthma while 18 (17.0%) had persistent asthma which was mild persistent in 10 (9.5%) and moderate persistent in 8 (7.5%). None of the study participants had severe persistent asthma.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the children as related to asthma control

Children from low socioeconomic class were more likely to have suboptimal asthma control as six (50.0%) of the 12 children from low social class compared to 13 (13.8%) of the remaining 94 children from middle and upper class had suboptimal control (χ2 = 6.088, df = 1; P = 0.014).

Similarly, children with caregivers having poor asthma knowledge were more likely to have suboptimal asthma control (50.0% vs. 4.1%; χ2 = 32.056; df = 1; P < 0.01). There is no significant association between the gender, age, caregivers' level of education and occupation, and the level of asthma control in the children [Table 1].

Comorbid condition and triggers as related to asthma control in the children

Children with asthma who had associated allergic rhinoconjunctivitis were more likely to have suboptimal asthma control as 13 (26.0%) of the 50 children with concomitant allergic rhinoconjunctivitis compared to 6 (10.7%) of the remaining 56 children with no rhinoconjunctivitis had suboptimal asthma control (χ2 = 2.928; df = 1; P = 0.001). Likewise, children with no known triggers of acute exacerbation were more likely to have suboptimal asthma control (30.0% vs. 10.5%; χ2 = 2.828; df = 1; P = 0.004).

Household exposure to cigarette smoke was significantly associated with suboptimal asthma control as 9 (47.4%) of the 19 children with household exposure compared to 8 (9.4%) of the remaining 85 children without household exposure, had suboptimal asthma control [Table 2].

Previous asthma-related hospitalization, family history of asthma, and type of fuel used for household cooking were not significantly associated with the level of asthma control among the children [Table 2].

Predictors of suboptimal asthma control in the children

The variables found to be significantly associated with suboptimal asthma control in the study participants [Tables 1 and 2] were further analyzed using binary logistic regression [Table 3], parental low socioeconomic class (OR = 6.231; 95% CI = 1.022–8.496; P = 0.005) and poor caregivers' knowledge about childhood asthma (OR = 7.607; 95% CI = 1.011–10.481; P = 0.007) were the independent predictors of suboptimal asthma control among the study participants.

Table 3.

Predictors of suboptimal asthma control among the study participants

Discussion

This study has presented data on childhood asthma on Ilesa; South West Nigeria highlighting that about one in every 5–6 (17.9%) study participants aged 2–14 years attending the pediatric chest clinic of the WGH, Ilesa during the study had suboptimal asthma control. Low socioeconomic class, poor caregivers' knowledge about childhood asthma, unrecognized triggers, exposure to household cigarette smoke, and concomitant allergic rhinoconjunctivitis were significantly associated with suboptimal asthma control among the study participants.

The prevalence of suboptimal asthma control among the study participants (17.9%) was similar to 14.6% reported among Japanese children in a web-based study by Sasaki et al.[23] It is, however, low compared to 64.0% among children with asthma attending a center in Saudi Arabia[13] and 64.4% reported by Ayuk et al.[16] from South East Nigeria. van Dellen et al.[12] reported 40.0% prevalence of suboptimal asthma control among multiethnic children in a center in the Netherland. Studies from other developed countries reported prevalence ranging from 32.0% to 64.0%.[9,10,11] The relatively low prevalence of suboptimal asthma control reported in this study and the Japanese study may be related to high prevalence of mild intermittent forms (83.0%) of asthma reported in these studies compared to the more severe persistent forms seen among children in the earlier cited studies.[9,10,11,12] Furthermore, children from rural and periurban nonaffluent countries like the study site who live in less hygienic environment are believed to be exposed earlier in life to viral infections and helminthic infestations causing upregulation of Th1 helper cells at the expense of proallergic Th2 helper cells – hygiene hypothesis.[24] These may reduce the prevalence of severe forms of asthma in them hence the reduced prevalence of more severe persistent asthma and suboptimal asthma control.[24]

The high prevalence of children with mild forms of asthma (mild intermittent asthma) in the present study may be related to the easy access of the populace to the study site. The WGH though is a tertiary annex of the university teaching hospital is located in a semi-urban region right in the center of town[17] and patients can walk into the hospital to access care even without necessarily being referred from a peripheral center. Technically, the facility also provides primary and secondary healthcare to the populace. This also contributes to the low prevalence of children with suboptimal asthma control observed in this study.

Low socioeconomic class is an important predictor of suboptimal asthma control in this study which is similarly reported by Bloomberg et al.[9] and Chen et al.[10] in America. Stanford et al.[25] also reported caregivers' unemployment closely related to low social class as a significant predictor of poor asthma control in a cohort of asthmatics in the USA. Low socioeconomic class puts the caregivers at risk of not being able to meet the financial obligations in terms of procuring the appropriate rescue and controller medications for optimal asthma control.[1,6] Secondly, children with asthma from low socioeconomic class are more likely to be exposed to other risks factors for asthma exacerbation and respiratory tract infections like indoor and outdoor air pollution.[26] People from low social class particularly from low- and middle-income countries are more likely to use biomass fuel for cooking lighting and heating thereby predisposing them to frequent acute asthma exacerbation and recurrent chest infection[27] with subsequent suboptimal asthma control. This implies that making childhood asthma care easily accessible and affordable by all the socioeconomic classes in the community will go a long way in ensuring good asthma control.

Poor parental asthma knowledge assessed using the AKQ was also found in this study as an independent predictor of suboptimal asthma control. This finding was corroborated by Awan and Munir[28] in Pakistan where poor parental knowledge about childhood asthma was associated with under usage of controller medications and subsequent high prevalence of suboptimal asthma control. McGhan et al.[29] also reported poor parental knowledge and perception of childhood asthma was significantly related to suboptimal asthma control among Canadian children with asthma. Children depend on their parents and/or caregiver for the control of their asthma, the importance of parental and child comprehensive asthma education including prevention and control cannot be overemphasized.

Exposure to household tobacco smoke was significantly associated with suboptimal asthma control in the study which was similarly reported by McGhan et al.,[29] Yamasaki et al.,[30] and Morkjaroenpong et al.[31] also reported that tobacco smoke increases the severity and frequency of acute exacerbation among children with asthma. Also Millet et al.[32] reported a significant fall in the frequency of hospitalization of childhood asthma in England following the introduction of smoke-free legislation. Avoidance of exposure to tobacco smoke in children with asthma may assist in avoiding exacerbation and ensuring control of the symptoms of asthma.

Concomitant presence of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children with asthma makes them more likely to have suboptimal control of the symptoms of asthma in this study. This is similar to reports by Sasaki et al.[23] among Japanese children. Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis is a common occurrence in children with asthma as they form part of the “atopic march.”[33,34] It is found in 47.2% of children with asthma in this study which is similar to reports from other centers.[33,34] Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis predisposes children to infections of the respiratory tract which are important triggers of acute exacerbation in asthmatics.[32] Furthermore, it increases the cost of management of asthma and predispose to emotional and behavioral problems in asthmatics[34] thereby leading to suboptimal asthma control. These imply that children being managed for asthma should be thoroughly evaluated for allergic conditions including rhinoconjunctivitis and if presence, should be appropriately managed to ensure adequate asthma control.

One of the pillars of proper asthma education and control is the need to avoid triggering factors of acute exacerbation. In situations where the triggers of asthmatic attacks were not known, ensuring optical symptoms control becomes difficult. Unrecognized or unknown triggers of asthma exacerbation were significantly associated with suboptimal asthma control in this study. Awan and Munir[28] also reported unknown triggers as being associated with frequent asthma exacerbation. The need to recognize triggers of acute exacerbations and promptly treat, avoid and or manage these triggers including environmental manipulations will go a long way in ensuring optimal asthma control and improve the quality of life.

Worthy of note from this study is that caregivers' level of educational qualifications did not significantly affect the level of asthma control, but caregivers' level of knowledge about childhood asthma did affect the level of asthma control.[35] This may be due to the fact that asthma knowledge affects the perception of the disease, and ultimately affects the management and motivation to ensure adequate control. Highly educated caregivers may have wrong perceptions and inadequate knowledge about the pathogenesis, course, triggers, and medication use as related to childhood asthma and these definitely will affect the level of control as observed in this study and other studies.[28,35]

This study has added to the few data on childhood asthma control and factors associated with it in a developing country. We assessed a variety of social, demographic, environmental, and clinical factors which may affect asthma control in children. The levels of asthma control and caregivers' knowledge about childhood asthma in this study were objectively assessed using validated instruments. These constitute great strengths of this study.

We, however, appreciate the limitations that parental and children perception of asthma and the presence of psychosocial and emotional problems in the school-aged children recruited for this study were not assessed and these may impact on the levels of asthma control. In addition, recall bias may also be present as an objective assessment of control through the use of lung function assessment was not done for all the study participants in this study. Nonetheless, this study has been able to highlight significant factors that can predict suboptimal asthma control among children in Ilesa. We advocate for multicenter, community-based approach to assessing factors affecting childhood asthma control in developing countries as hospital-based study may not totally reflect the true picture of what is happening in the community.

Conclusion

Optimal childhood asthma control is desirable and achievable, in fact, it is highly recommended in the guidelines for childhood asthma management. However, children with asthma who have concomitant allergic rhinoconjunctivitis or with unrecognized triggers of acute exacerbations especially those from low socioeconomic homes and those whose caregivers have poor knowledge about childhood asthma are at increased risk of having suboptimal asthma control. The implications of these to the family physicians and primary care practitioners in our setting or similar settings are that children with asthma should be carefully assessed for comorbidities especially allergic rhinoconjunctivitis because its presence may affect the control of asthma symptoms. In addition, the primary care physicians should ensure that children with asthma and their caregivers have adequate knowledge about the condition particularly as related to avoidance of triggers of acute exacerbations to facilitate good asthma symptoms control. On the part of health policy makers, making childhood asthma care easily accessible and affordable may assist the clinicians, caregivers, and parents to ensure good childhood asthma control.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby acknowledge the contributions of the clinicians and nurses who assisted in the running of the weekly pediatric chest clinic of the WGH, Ilesa. The children and their parents/caregivers who participated in the study and patiently filled the study questionnaire are also acknowledged.

References

- 1.The Global Asthma Report 2014. Auckland, New Zealand: Global Asthma Network. 2014. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 15]. Available from: http://www.globalasthmanetwork.org .

- 2.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Program. The global burden of asthma: Executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy. 2004;59:469–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falade AG, Olawuyi JF, Osinusi K, Onadeko BO. Prevalence and severity of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema in 6- to 7-year-old Nigerian primary school children: The international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. Med Princ Pract. 2004;13:20–5. doi: 10.1159/000074046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean BB, Calimlim BM, Kindermann SL, Khandker RK, Tinkelman D. The impact of uncontrolled asthma on absenteeism and health-related quality of life. J Asthma. 2009;46:861–6. doi: 10.3109/02770900903184237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams SA, Wagner S, Kannan H, Bolge SC. The association between asthma control and health care utilization, work productivity loss and health-related quality of life. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:780–5. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181abb019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang LY, Zhong Y, Wheeler L. Direct and indirect costs of asthma in school-age children. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2:A11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute: National Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. 2007. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm .

- 9.Bloomberg GR, Banister C, Sterkel R, Epstein J, Bruns J, Swerczek L, et al. Socioeconomic, family, and pediatric practice factors that affect level of asthma control. Pediatrics. 2009;123:829–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen E, Bloomberg GR, Fisher EB, Jr, Strunk RC. Predictors of repeat hospitalizations in children with asthma: The role of psychosocial and socioenvironmental factors. Health Psychol. 2003;22:12–8. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dick S, Doust E, Cowie H, Ayres JG, Turner S. Associations between environmental exposures and asthma control and exacerbations in young children: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e003827. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dellen QM, Stronks K, Bindels PJ, Ory FG, Bruil J, van Aalderen WM PEACE Study Group. Predictors of asthma control in children from different ethnic origins living in Amsterdam. Respir Med. 2007;101:779–85. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandhi PK, Kenzik KM, Thompson LA, DeWalt DA, Revicki DA, Shenkman EA, et al. Exploring factors influencing asthma control and asthma-specific health-related quality of life among children. Respir Res. 2013;14:26. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Muhsen S, Horanieh N, Dulgom S, Aseri ZA, Vazquez-Tello A, Halwani R, et al. Poor asthma education and medication compliance are associated with increased emergency department visits by asthmatic children. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10:123–31. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.150735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garba BI, Ballot DE, White DA. Home circumstances and asthma control in Johannesburg. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;27:182–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayuk AC, Oguonu T, Ikefuna AN, Ibe BC. Asthma control and quality of life in school- age children in Enugu South East, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2014;21:160–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilesa West Local Government Area. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 05]. Available from: http://www.info@ilesawestlg.os.gov.ng .

- 18.Park K. Environment and health. In: Park JE, Park K, editors. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. Jabalpur: Banarasidas Bhanot and Company; 2006. pp. 521–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyedeji GA. Socioeconomic and cultural background of hospitalized children in Ilesa. Niger J Paediatr. 1985;13:111–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho J, Bender BG, Gavin LA, O'Connor SL, Wamboldt MZ, Wamboldt FS. Relations among asthma knowledge, treatment adherence, and outcome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:498–502. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams HC, Burney PG, Hay RJ, Archer CB, Shipley MJ, Hunter JJ, et al. The U.K. working party's diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:383–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA (2) LEN and AllerGen) Allergy. 2008;63(Suppl 86):8–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasaki M, Yoshida K, Adachi Y, Furukawa M, Itazawa T, Odajima H, et al. Factors associated with asthma control in children: Findings from a national Web-based survey. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25:804–9. doi: 10.1111/pai.12316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The 'hygiene hypothesis' for autoimmune and allergic diseases: An update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanford RH, Gilsenan AW, Ziemiecki R, Zhou X, Lincourt WR, Ortega H. Predictors of uncontrolled asthma in adult and pediatric patients: Analysis of the Asthma Control Characteristics and Prevalence Survey Studies (ACCESS) J Asthma. 2010;47:257–62. doi: 10.3109/02770900903584019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 02]. World Health Organization. Burden of Disease from Household Air Pollution for 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/phe/health_topics/outdoorair/databases/FINAL_HAP_AAP_BoD_24March2014.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, Hibberd PL, Kurmi OP, Lam KB, et al. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:823–60. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awan AS, Munir SS. Asthmatic children; knowledge, attitude and practices among caregivers. Prof Med J. 2015;22:130–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGhan SL, MacDonald C, James DE, Naidu P, Wong E, Sharpe H, et al. Factors associated with poor asthma control in children aged five to 13 years. Can Respir J. 2006;13:23–9. doi: 10.1155/2006/149863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamasaki A, Hanaki K, Tomita K, Watanabe M, Hasagawa Y, Okazaki R, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and its effect on the symptoms and medication in children with asthma. Int J Environ Health Res. 2009;19:97–108. doi: 10.1080/09603120802392884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morkjaroenpong V, Rand CS, Butz AM, Huss K, Eggleston P, Malveaux FJ, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and nocturnal symptoms among Inner-city children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:147–53. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.125832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millett C, Lee JT, Laverty AA, Glantz SA, Majeed A. Hospital admissions for childhood asthma after smoke-free legislation in England. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e495–501. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Melo KC, Naspitz CK. Is rhinitis alone or associated with atopic eczema a risk factor for severe asthma in children? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:121–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruokonen M, Kaila M, Haataja R, Korppi M, Paassilta M. Allergic rhinitis in school-aged children with asthma – Still under-diagnosed and under-treated. A retrospective study in a children's hospital? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(1 Pt 2):e149–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rastogi D, Madhok N, Kipperman S. Caregiver asthma knowledge, aptitude, and practice in high healthcare utilizing children: Effect of an educational intervention. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2013;26:128–39. doi: 10.1089/ped.2013.0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]