Abstract

Background:

Delivery of maternal health care services is a major challenge to the health system in developing countries. Provision of antenatal care (ANC) services is the major function of public health delivery system in India to improve maternal health outcomes and its impact on maternal morbidity and mortality. Studies are lack in documenting variation in utilization of ANC services between geographical regions of Andhra Pradesh (AP).

Objective:

The objective of this study is to assess variation in utilization of ANC services stratified by geographical region, type of delivery and determinants of utilization of ANC services in AP.

Methodology:

It is a cross-sectional study of District Level Household and Facility Survey-4 of the state of AP. Multistage, stratified and probability proportional to size sample with replacement was used. Around 3982 women who delivered after the year 2007 were considered for analysis. Binomial logistic regression was carried out to determine association of demographic, system level variables with adequate ANC.

Results:

Study reveals wide variation across four regions of AP in utilization of ANC services. Reception of adequate ANC was low in Rayalaseema region (27.9%) and high in North-coastal region (42.4%). The utilization of private health facilities for ANC services were highest in South-coastal region (73.2%) and lowest in North-coastal region (43.2%).

Conclusion:

Policy measures are to be adopted and implemented by government to address the demand-supply imbalance such as public health infrastructure and quality of services in underperforming districts of AP and to increase outreach of current programs by engaging communities.

Keywords: Andhra Pradesh, antenatal care, determinants, District Level Household and Facility Survey, geographical region, National Family Health Survey

Introduction

Delivery of maternal health care services remains a major challenge to the health system in developing countries.[1] More than three-quarters of maternal deaths in the world were found in the African region and South-East Asia, 53% and 25%, respectively.[2] The Southern states of India are highly advanced with respect to sociodemographic indicators. Indian Government listed eight states Uttaranchal, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Odisha, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh as Empowered Action Group states which are very poor with respect to socioeconomic and demographic status.[3] Antenatal care (ANC) services are primary function of the primary health care delivery system of a country, which aims a healthy society and is a component of continuum of care for controlling maternal morbidity and mortality. One of the important components of Safe Motherhood Initiative is the provision of good ANC to all pregnant women. ANC utilization is associated with greater knowledge of contraceptive among mothers and declined fertility rates. A community based study in rural Tamil Nadu suggested that ANC of women influences postpartum health seeking behavior.[4]

Women, not receiving proper ANC services during pregnancy in developing countries leading to poor birth outcomes. Previous studies revealed that countries which have improved their maternal health care services are successful in dropping the maternal morbidity or mortality rate.[5,6,7] The utilization of ANC services in India increased substantially over time, 66% in National Family Health Survey-2 (NFHS-2) to 77% in NFHS-3 while it remained static between NFHS-1 and NFHS-2.[8] Previous study findings revealed socioeconomic, demographic, and rural environmental conditions of the women are considered as essential determinants for ANC utilization.[9] Achievement of higher coverage of ANC in rural areas will remain challenging till the improvements in terms of quality of care and community participation is attained.[10] Place of delivery in India may be at home with or without the presence of a skilled birth attendant and institutional deliveries at public or private facilities. Public facilities are owned and financed by government with minimal costs. Private facilities are expensive, good amenities, and offering the best standard of care.[11] The Government of India introduced Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), a conditional cash assistance programme to promote institutional deliveries and to reduce maternal mortalities. In India, though 75.2% of pregnant women receive ANC, only 47% deliver in an institution.[12,13] Adolescent marriages were 30%–70% in the Indian subcontinent, based on United Nations Children's Fund survey of mothers of 20–24 years age-group.[14] Adolescent's maternal health care is crucial because early sexual and childbearing activities accelerate the risk of child and maternal morbidity or/and mortality.[15]

According to NFHS-4, 76.3% of pregnant women had received at least 4 ANC visits in the state of Andhra Pradesh (AP), 79.6% and 75.1% were from urban and rural areas, respectively. Krishna district had highest (88.2%), and Guntur district had lowest (68.4%) ANC visits among districts of AP.[16] Utilization of ANC is an evidence of early registration.[10] The previous study revealed that, as birth order increases, the percentage of women received at least three ANC decreases.[17] As per NFHS-2, majority of women from Maharashtra delivered at home (n = 559, 37%); with private and public facility deliveries accounting for 32% (n = 493) and 31% (n = 454), respectively.[18]

Regional variation exists in the utilization of ANC services in the state of AP, and inequities exist in availability and accessibility of health care services. Studies are lacking to identify determinants of ANC services in AP. This study objective is to know the utilization of ANC services, type of delivery and determinants of utilization of ANC services in AP.

Methodology

Sample design

District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-4) was a fourth round of nationwide survey conducted in 2012–2013. It is a multi-stage, stratified, probability proportional to size (PPS) sample with replacement, was adopted in 21 states of DLHS-4 (except Gujarat). The First Stage Unit (FSU) for urban areas is the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), Urban Frame Survey (UFS) blocks and Ultimate Stage Sampling Unit was the household (HH). UFS blocks in each district were stratified into million class cities, and nonmillion class cities and allotment of sample was proportional to relative sizes. The sample frame for selection of primary sampling units (PSU) for urban areas was provided by Survey Design and Research Division of NSSO. Urban areas in some districts were oversampled by taking more PSUs for districts with less than estimated 30% urban population. HH number as per PSU is 25; however, it varied for North-Eastern states and hilly districts such as Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh. While for rural areas, census 2001 villages were framed as FSU of sampling, stratified by size and selection by PPS. Households (HHs) listing in the FSU provided the sampling frame for selecting HHs at the second stage. List of HH preparation served as the sampling frame for selection of representative HHs. This involved mapping and listing of structures and HHs for each sampled PSU following the preparation of location and layout maps. Large sample villages (more than 300 HHs) were segmented as per DLHS-4. For villages with 300–600 HHs, the study had two segments almost with same size and one was selected randomly among them. For villages with more than 600 HHs, more than three segments were made with about 150 HHs each and two were selected at random. In urban areas, each UFS have no more than 300 HHs. Each HH distinct in had one lister and one mapper; this operation was completed in 2 months in advance of the survey. PSU was selected in each district from rural and urban sample frame followed by selection of HHs. The allocation of HHs is proportional to size of each substratum. Each selected rural/urban PSU is represented by 25 HHs.

Data collection

Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) was used for data collection in DLHS-4. Each investigator was provided with a mini laptop with bilingual questionnaire. This technique took minimum time for moving the questionnaire for editing the data and entry, etc., from field to work area. CAPI data was uploaded to server (FTP account) located in Indian Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) on day to day basis. Bilingual questionnaires were collected in the local language and English from HHs, visitors stayed in HH during the night before interview and ever married women in DLHS-4.

Standardized HH survey instrument was used to collect information on main source of drinking water, toilet facility, type of fuel used for cooking, caste and religion, education, morbidity and mortality details, multiple marriages, socioeconomic status, and assets possessed etc., since January 2008. Clinical, Anthropometric, and Bio-Chemical tests were also carried out for selected HHs.

Ever-married women's questionnaire was used to collect information from women of 15–49 years on women's characteristics, age, educational status, marriage, pregnancy, mode of delivery including history of induced, spontaneous abortions and stillbirths, antenatal, natal and postnatal care, institutional delivery, financial assistance from JSY or any other government schemes, nature of complications during pregnancy for recent births and birth order, immunization and child care, contraception and fertility preferences, reproductive health including knowledge about HIV/AIDS.

DLHS-4 survey was conducted in the state of AP from 2012 to 2013. Information was collected from 20,490 HHs, 12,163 from rural, and 8,327 from urban regions. 16,498 of total ever married women were surveyed (9,859 from rural and 6,639 from urban). Ever-married women of 3982 HHs (2502 from rural and 1480 from urban) delivered after year 2008 were considered for analysis.

Measures

The outcome or dependent variable is ANC: The odds of mother receiving (i) adequate care and (ii) inadequate care. Adequate care is defined as mother availing at least 4 ANC visits, at least 1 tetanus toxoid injection and consumption of 100 or more iron-folic acid tablets. Inadequate care is defined as mothers availing <4 ANC visits, no TT injection and consumption of <100 iron-folic acid tablets. Independent variables were age of mother, social group, education, occupation, age at marriage of mother, family size, wealth quintile and regions of state of AP – North-coastal (Vishakhapatnam, Vizianagaram, Srikakulam), Delta (East Godavari, Krishna, West Godavari), South Coastal (Guntur, Prakasam, Nellore), and Rayalaseema (Anantapur, Chittoor, Kadapa, Kurnool).

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Frequency and percentage for categorical variables were calculated. Binomial logistic regression was carried out for analysis of determinants of adequate ANC. Chi-square analysis was carried out to determine assumption of independence of each variable and variables with minimum P = 0.25 were selected. Backward likelihood ratio was carried out to find predictors for adequate ANC. The goodness-of-fit for the final model was tested by Hosmer and Lemeshow test.

Results

Regional variation in maternal health services utilization

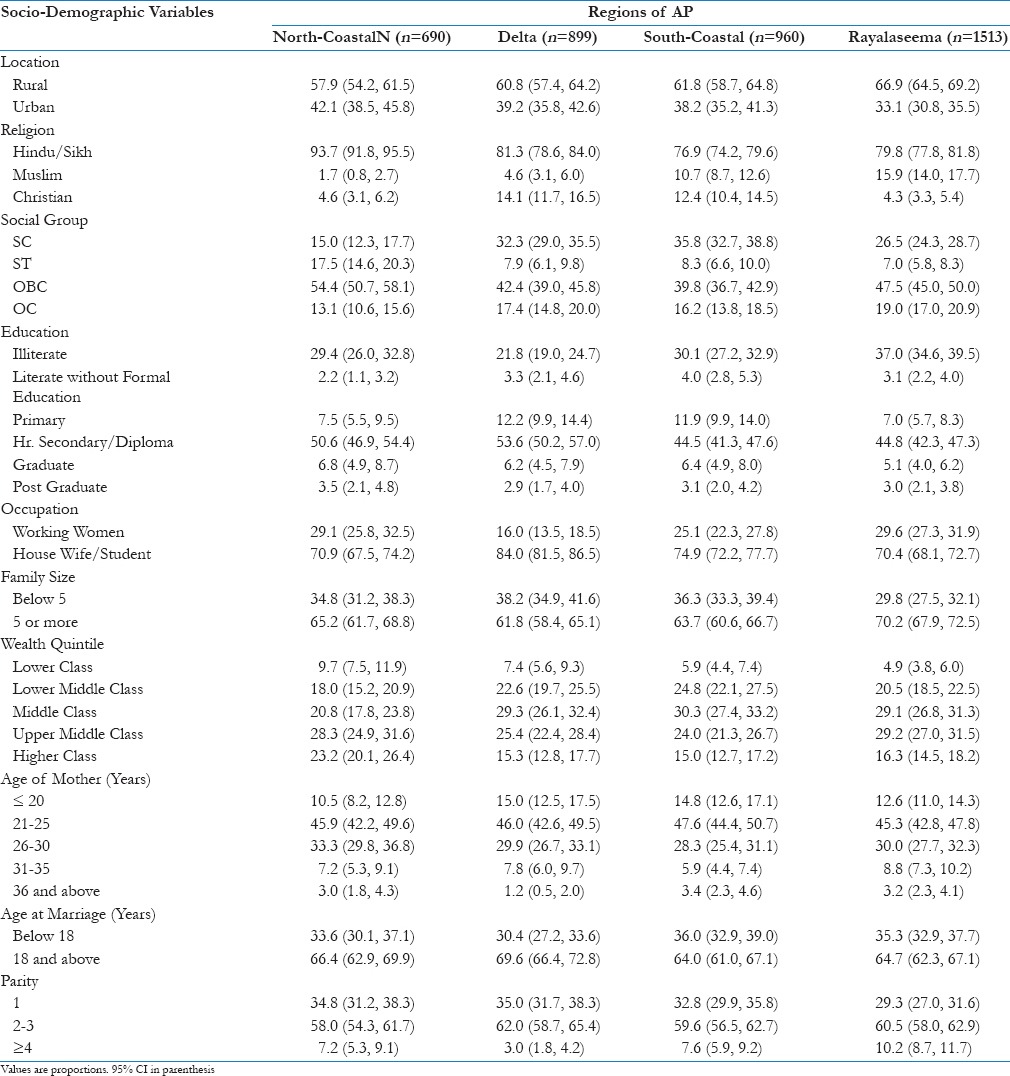

Table 1 reveals mothers with higher secondary education had availed antenatal services in majority among four regions of the state of AP. The majority of mothers availing antenatal services were housewives among all regions. Mothers of middle class had availed antenatal services in majority across all regions. About 33% of mothers who had availed antenatal services were married below 18 years of age across all regions.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics by region of AP

Table 2 shows mothers receiving adequate ANC was highest in North-coastal region (42.2%) and lowest in Rayalaseema region (30.2%). Private hospitals are main source of provision of antenatal services in South Coastal, Rayalaseema, and Delta regions of AP. At least 80% of mothers had registered for ANC services in the first trimester across all regions of AP. Consumption of at least 100 iron-folic acid tablets by pregnant mothers is 35.9% in Rayalaseema, while 45.5% and 45.7% in North-coastal and Delta regions. Pregnant women reception of two shots of tetanus vaccine is high in South coastal (72.6%) and low in Delta (52.6%) regions.

Table 2.

Components of ANC in each region of AP

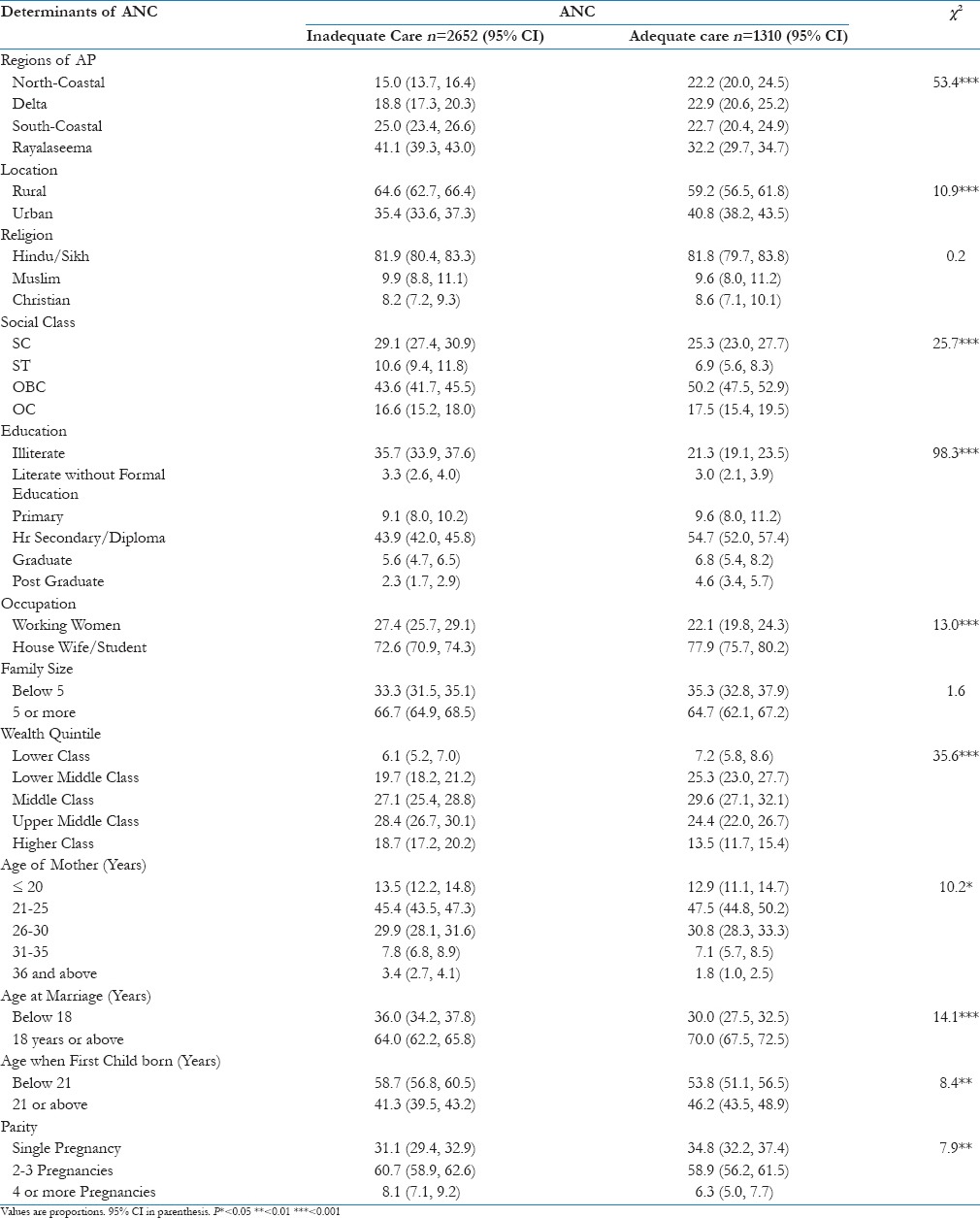

Table 3 illustrates 66.1% and 51.8% of pregnant mothers with higher education and above, respectively had received adequate and inadequate ANC services, while 21.3% and 35.7% of illiterate mothers received adequate and inadequate ANC services.

Table 3.

Characteristics of mothers receiving ANC services

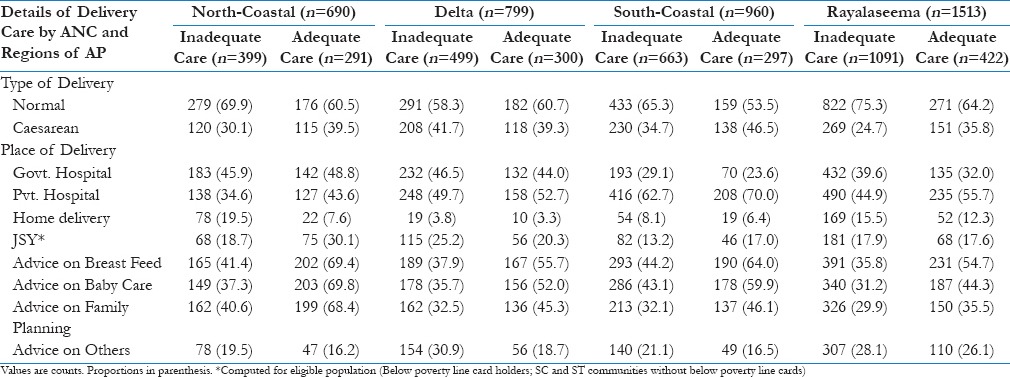

Table 5 depicts higher institutional deliveries in Government hospitals at North Coastal (47.3%) region, while it was higher in private hospitals at South Coastal (66.3%), Delta (51.2%) and Rayalaseema (50.0%) regions. Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) programme utilization was higher in North Coastal (24.4%) and Delta (22.7%) regions compared to South Coastal (15.1%) and Rayalaseema (17.7%) regions.

Table 5.

Components of perinatal care by adequacy of care in each region of AP

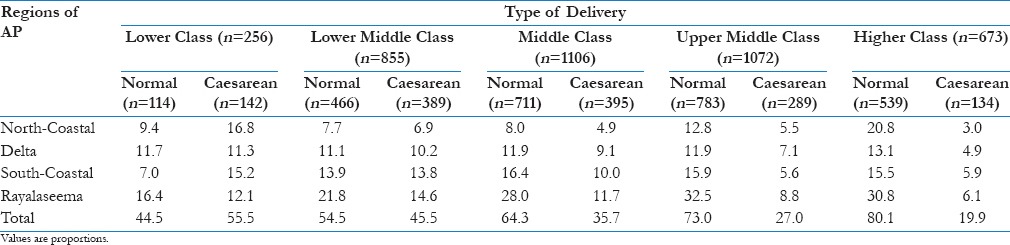

Table 6 reveals cesarean delivery in mothers were 55.8%, 45.5%, 35.8%, 27%, and 19.8% in lower class, lower middle class, middle class, upper middle class and upper class, respectively.

Table 6.

Type of delivery of each region stratified by wealth quintile

Factors associated with utilization of maternal health services

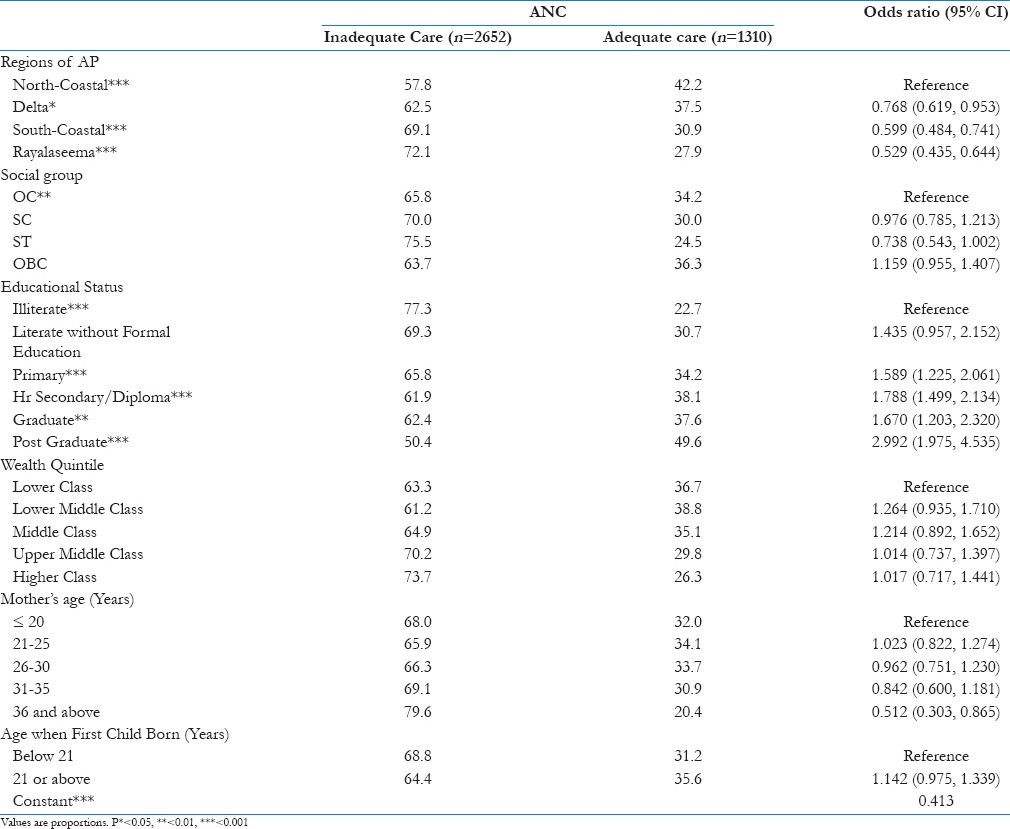

Table 4 shows an association of variables with the adequacy of ANC. Pregnant mothers of Delta region, South Coastal and Rayalaseema of 23.2%, 40.1%, and 47.1%, respectively were less likely to receive adequate ANC than North-coastal regions after adjusting for other variables. Postgraduate and graduate pregnant women of 200% and 67%, respectively were more likely to receive adequate ANC services than illiterate, pregnant women.

Table 4.

Binomial Logistic Regression Summary

Discussion

Reception of adequate ANC services is 43.7% in the state of AP compared to 32.9%, 42.2%, and 45% in Karnataka, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu, respectively.[16] Mothers receiving antenatal checkup in I trimester is 82.5% and 82.4% in AP based on DLHS4 and fourth round of NFHS-4, respectively. No variation in availing antenatal checkup in I trimester across four regions of AP. Wide variation in utilization of ANC services across four regions of AP with the reception of adequate care is low in Rayalaseema region (27.9%) and high in North-coastal region (42.4%). Hence, variation of utilization of ANC services across regions is due to demand and supply-side barriers of access to maternal health services in communities.[19,20]

Supply-side barriers include poor attitude of health care staff of public health facilities toward communities at the lower end of wealth quintile. Unavailability of medicines at the health center had become a major share of out of pocket expenses for poor HHs hindering them to avail maternal health services.[21] Unavailability of health providers at public health facilities is the frequent complaint received from the communities and forcing them to utilize the private health facilities, increasing the cost of care and a major economic burden to them.[22] Utilization of private health facilities for ANC services is higher across all regions of AP and highest in South-coastal region (73.2%) and lowest in North-coastal region (43.2%).

Demand-side barriers override supply-side and are a major cause of inadequate utilization of maternal health services.[21] First, indirect consumer costs like transportation to health facility is a major barrier for availing ANC services and institutional deliveries. Transport costs due to distant health facility will affect the utilization of services.[20,22] Second, financial constraint is one of the major reasons for home deliveries,[20] hence government of India launched JSY scheme on April 12, 2015, aimed to reduce neonatal and maternal mortality rates by promoting institutional delivery.[23] JSY scheme utilization is 15%, 17.7%, 22%, and 24% in South-coastal, Rayalaseema, Krishna and North-coastal districts, respectively and is inversely proportional to institutional deliveries at private hospitals. Low utilization of the scheme might be due to lack of awareness of scheme and no motivation from health workers in utilizing it. Third, lack of community engagement, in seeking health care services, institutional deliveries, and perinatal care, is one of the barriers in utilizing services. Evidence from previous intervention studies reveal Lady Health Workers (LHW) are effective in promoting maternal health services by various approaches, for example, home visits, home management, and facilitated referral.

Home visits involve provision of basic ANC (nutrition counseling, screening for common illness, iron-folic acid supplementation and TT administration), newborn care preparedness and home-based perinatal care by LHW.[24] Another approach like LHW organizing group sessions in the community to promote ANC, use of clean kits at delivery, institutional delivery, identifying danger signs of pregnancy, and promotion of health seeking behavior.[25] Evidence from previous studies shows recruitment of ASHA health worker in rural areas had increased the utilization of maternal health services (registration in the first trimester, ANC visits, institutional deliveries, deliveries to be announced, immunization).[26]

The strategies designed for engaging the community are not meeting the targets due to lack of knowledge of community about strategies designed without understanding three fundamental influences of decision-making process for the woman making health care decision. These influences are gendered decision-making norms, multigenerational dialogue, and appropriate communication.

Gendered decision-making norms play a vital role in influencing health-seeking behavior and health outcomes. Gender equality and women empowerment are essential to increase utilization of maternal health services. At the HH level disempowerment of women, results to lowered access to resources such as education, employment, income, and limits their decision-making power.[22] Factors increasing women role in decision-making process in a hold is their education and contribution to HH income. Our study corroborates these findings that women with secondary education had a higher probability of adequate ANC and institutional delivery. The difference in education between wife and husband is also crucial in influencing decision-making process.[27]

Multigenerational gaps exist as social norms, values, traditions, and customs inhibit mothers to transfer knowledge and experiences to their daughters resulting in lack of sexual education and preparedness for motherhood.[28,29] Generational gaps are growing reality due to increased urbanization and proliferation of nuclear families leading to increasing disconnection of urban HHs from their traditional roots, conflict between social beliefs can arise. Intergenerational dialogue is necessary to achieve consensus on best practices in motherhood. The lack of communication between pregnant women and health provider leads to poor health outcomes. ANC can be delivered by frontline providers including midwives, nurses, and community health workers, provided they are well trained. Health information should be designed in consultation with local women and disseminated in two-way communication considering literacy levels of mothers.

Limitations

A limitation of DLHS-4 survey is, limited data were collected of supply-side factors at village level about the availability of health care infrastructure, but no information was collected about barriers of accessibility and quality of maternal health services from HHs. Another limitation of the study is retrospective reporting, which involves recall bias and therefore, impacts the reliability of data.

Conclusion

Wide variation of utilization of maternal health services across four regions of AP is because of lack of awareness of mothers in various health schemes, financial constraints, and lack of awareness of HHs of incentives for institutional delivery. Health interventions should be designed to tackle the barriers such as effective training of ASHA worker to educate and motivate mothers about newborn and perinatal care, and engage communities for women empowerment, identification of community volunteers to motivate women to seek health care. Policy measures to be adopted to periodically monitor the supply-side issues like the application of Geographical Information System to assess the accessibility of maternal health services in underperforming districts, and improving infrastructure, and quality of care in public health facilities.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to IIPS, Mumbai for providing DLHS-4 data.

References

- 1.Patton GC, Viner RM, Linh le C, Ameratunga S, Fatusi AO, Ferguson BJ, et al. Mapping a global agenda for adolescent health. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:427–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, UNICEF. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank estimates [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh RK. Lifestyle behavior affecting the prevalence of anemia among women in EAG states, India. J Public Health. 2012;21:279–88. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra US, Roy TK, Rajan SI. Antenatal care and contraceptive behavior in India: Some evidence from the National Family Health Survey 3. Fam Welf. 1998;44:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rejoice PR, Ravi Shankar AK. Differentials in maternal health care service utilization: Comparative study between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. World Appl Sci J. 2011;14:1661–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartlett LA, Mawji S, Whitehead S, Crouse C, Dalil S, Ionete D, et al. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: Maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999-2002. Lancet. 2005;365:864–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilpatrick SJ, Crabtree KE, Kemp A, Geller S. Preventability of maternal deaths: Comparison between Zambian and American referral hospitals. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:321–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mumbai: IIPS; 2008. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005.06: Uttar Pradesh. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fatmi Z, Avan BI. Demographic, socio-economic and environmental determinants of utilisation of antenatal care in a rural setting of Sindh, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:138–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy MP, Mohan U, Singh SK, Singh VK, Srivastava AK. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services in rural Lucknow, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2013;2:55–9. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.109946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thind A, Mohani A, Banerjee K, Hagigi F. Where to deliver. Analysis of choice of delivery location from a national survey in India? BMC Public Health. 2008;8:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devadasan N, Elias MA, John D, Grahacharya S, Ralte L. A conditional cash assistance programme for promoting institutional deliveries among the poor in India: Process evaluation results. In: Richard F, Witter S, De Brouwere V, editors. Reducing Financial Barriers to Obstetric Care in Low-Income Countries. Antwerp, Belgium: ITG Press; 2008. pp. 257–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fact Sheet. District Level Household Facility Survey-3, 2007-08; AP. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. 2010. [Last accessed on2016 Sep 06]. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/pdf/rch3/state/India.pdf .

- 14.United Nations Children's Fund. Progress for Children: A World Fit for Children Statistical Review. Protecting against Abuse, Exploitation and Violence: Child Marriage. 2011. [Last accessed on 2011 Jan 19]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/progressforchildren/2007n6/index_41848.htm .

- 15.Rosenfield A, Charo RA, Chavkin W. Moving forward on reproductive health. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1869–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mumbai: IIPS; 2015. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), India, 2015-16: INDIA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh RK, Patra S. Differentials in the utilization of antenatal care services in EAG states of India. Int Res J Soc Sci. 2013;2(Suppl 11):28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mumbai: IIPS; 2000. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998-99: India. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: Influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:69–79. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elmusharaf K, Byrne E, O'Donovan D. Strategies to increase demand for maternal health services in resource-limited settings: Challenges to be addressed. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:870. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2222-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piet-Pelon NJ, Rob U, Khan ME. Dhaka: Karshaf Publishers; 1999. Men in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan: Reproductive Health Issues; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishor S, Gupta K. Gender equality and womens empowerment in India. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) India 2005-06 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 06]. Available from: http://www.nhp.gov.in/janani-suraksha-yojana-jsy-_pg .

- 24.Baqui AH, El-Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, Ahmed S, Williams EK, Seraji HR, et al. Effect of community-based newborn-care intervention package implemented through two service-delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1936–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhutta ZA, Soofi S, Cousens S, Mohammad S, Memon ZA, Ali I, et al. Improvement of perinatal and newborn care in rural Pakistan through community-based strategies: A cluster-randomised effectiveness trial. Lancet. 2011;377:403–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62274-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padda P, Devgun S, Gupta V, Chaudhari S, Singh G. Role of ASHA in improvement of maternal health status in northern India: An urban rural comparison. Indian J Community Health. 2013;25:465–71. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quisumbing AR, Maluccio JA. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2000. Intrahousehold allocation and gender relations: New empirical evidence from four developing countries. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varga CA. How gender roles influence sexual and reproductive health among South African adolescents. Stud Fam Plann. 2003;34:160–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchinson MK, Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Braverman P, Fong GT. The role of mother-daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: A prospective study. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]