Abstract

Background:

Over the past decade, gender equality and women's empowerment have been explicitly recognized as key not only to the health of nations but also to social and economic development. The aim of the present study was to assess the effectiveness of a mixed methods' participatory group education approach to introduce gender equity to adolescent school children. It also assessed baseline and postintervention knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding gender equity, sexual and reproductive health among adolescent students in government-aided schools, and finally, compare the pre- and post-intervention gender equitable (GE) attitudes among the study participants.

Methodology:

A government-aided school was selected by nonprobalistic intentional sampling. On 5 predesignated days, willing students were included in the intervention which included a pretest, a group of educational-based participatory mixed methods' intervention followed by a posttest assessment. A total of 186 students participated in the study.

Results:

Girls had better baseline GE scores as compared to boys and they also improvised more on the baseline scores following the intervention.

Conclusion:

The present mixed method approach to introduce gender equity to adolescent school children through a group education-based interventional approach proved to be effective in initiating dialog and sensitizing adolescents on gender equity and violence within a school setting.

Keywords: Adolescents, gender equity, mixed methods, school students, violence

Introduction

Gender inequality damages the physical and mental health of millions of girls and women across the globe, and also of boys and men despite the many tangible benefits, it gives men through resources, power, authority, and control.[1] Different gender norms exist for adolescent boys and girls,[2] especially in India. Evidence is increasing that gender norms – social expectations of appropriate roles and behavior for men (and boys) and women (and girls) – directly affect attitudes and health-related behavior. This has implications in multiple areas such as HIV prevention, sexual and reproductive health (SRH), use and experience of violence (gender-based), domestic chores, parenting, and men's participation in child, newborn, and maternal health.[3]

Adolescence is a time to explore and experiment with beliefs about roles in intimate relationships. It is necessary to reach adolescents to sensitize them with programs that address gender equity and prevention of gender-based violence before expectations, attitudes, and behaviors are well developed.[4] Sets of effective actions identified include “working with boys and men to transform masculinist values and behaviors that harm women's health and their own.”[1]

In working with adolescents, programs extended to schools and community settings have seen to more impact.[4] Schools are the only places outside the home where children are in a familiar, comfortable environment, and supervised by trusted adults. They have a great potential to shape gender norms and behavior and can serve as a canvass to initiate dialogs on gender equity and health with adolescents. In addition, girls who have been educated about menarche and early menstrual patterns will experience less anxiety when they occur.[5]

Studies have shown that less egalitarian gender norms threaten the sexual health and well-being of adolescents.[2,6,7] Adolescent boys with less egalitarian gender norms are more likely to engage in sexual risk behavior, such as having multiple sexual partners. Adolescent girls with less egalitarian gender norms are more vulnerable to negative SRH outcomes, such as experiencing sexual coercion.[8,9] The importance of gender for adolescents' sexuality is also recognized by the United Nations Population Fund and the World Health Organization who recognize the need to address gender as an “upstream” antecedent of adolescents' sexual health behavior.[10,11]

Sensing a priority area, the present study was planned to introduce gender equity, abuse, and violence to adolescent school students through a participatory mixed method approach and assess its effectiveness through changes of participants' pre- and post-intervention scores.

Methodology

Study design

The present study was a cross-sectional study. The Institutional Ethics Committee approval was taken before initiation of the study.

Setting

The study was conducted in a government-aided private school in an urban slum of Hyderabad.

Study population

Adolescents of age group 13–16 years were eligible to participate in the study.

Methods

Prior permission was taken from the school authorities. Parents and teachers were also briefed on the objectives of the study. Informed consent was taken from participant's parents before initiating the study. A brainstorming of potential activities was done. The teachers had discussions with students to seek their inputs on the activities that would interest them.

The study was finally conducted during five regular predesignated school days for 120 min each day. All students (13–16 years) in classes 9th and 10th who were present on 1st day were invited to participate in the study. Enrolled students who were not present were excluded from the study as were eligible students who were absent on the day of initiation of study.

Girls and boys were stationed in separate classes for the intervention period as deemed culturally appropriate in the study setting so they could uninhibitedly communicate their concerns regarding gender, menstruation, puberty, and sexual abuse.

As an initial step, on day 1, assessment of baseline knowledge, attitudes, and practices of participants regarding gender equity, SRH was done completing a self-administered questionnaire which included certain sociodemographic variables such as age (completed number of years), mothers' occupation, and certain household possessions. It included the gender equitable measurement (GEM) scale.[12] A 5-day long intervention followed the initial assessment. The workshop-based intervention used mixed participatory methods for group education which included ice breaking sessions, stories, games, role plays, demonstrations using audio-visual aids, debates, and group discussions. Posters on gender equity and violence were put across the school from 2 days before the study; drawing and essay writing competitions were organized for the entire week of the study.

Each session was conducted for 120 min. It included three broad themes:

(1) Gender: Gender equality, equity, and discrimination (What is gender? Division of work) (2) My body (Body and hygiene. Puberty: Changing body and changing mind. Respecting one's own and others' bodies) (3) Violence (What is violence? from violence to understanding, labeling violence, and importance of intolerance to violence). Certain questions on opportunities and discrimination such as whether girls get equal opportunity to education compared to boys were also raised. Why this difference? How does this affect their lives? Are not these issues important to discuss? Do we face violence? Who perpetrates more and who faces more? Should we do something to stop it? The intervention thus attempted to focus on deepening students' understanding of gender (roles and norms) and building skills to respond positively to discrimination and violence.

Postintervention on the final day (day 5), knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding gender equity, SRH assessment was done among study participants using the same instrument. The GEM scale[12] is a Likert-type scale where participant has to tick whether they agreed, disagreed, or were not sure about 18 statements that clustered around three themes, i.e., (1) roles/restrictions/privileges, (2) attributes, and (3) violence. Those who agreed with a statement, indicating support for gender inequality, received a score of 0. Those who were not sure received a score of 1 and those who disagreed, received a score of 2, indicating support for gender equality. Total scores ranged from a low of 0 (highly gender inequitable) to a high of 36 (highly GE). The students were categorized into three categories for further analysis: (1) those with low equality scores of 0–12, (2) moderate equality scores of 13–24, and (3) high equality scores of 24–36. Final scores were calculated before and after the intervention. A total of 186 students participated in the study, but some questionnaires could not be included as they were incomplete. A final sample of 168 pre- and post-intervention questionnaires was used for data entry and analysis.

Data entry was done and analysis was done by comparing the pre- and post-intervention scores of participants, using MS Excel 19.0 and SPSS.23.0 Statistical Package for Social Sciences by IBM.

Results

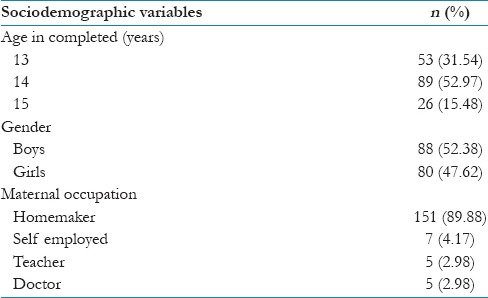

Sociodemographic characteristics and comparison of pre- and post-intervention scores among the participants are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

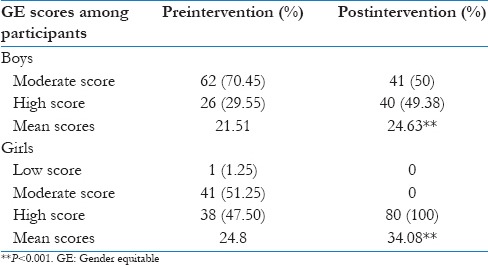

Table 2.

Distribution of gender equitable scores among participants

A highly significant difference (paired t-test) was observed between the pre- and post-intervention mean scores of study participants. Girls showed much more significant difference (improvement) in their performance compared to boys.

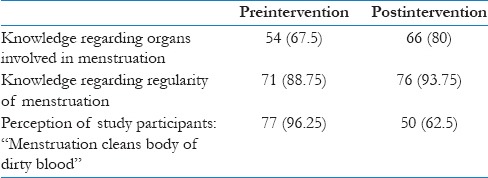

Knowledge and attitude regarding menstruation among girl participants is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Knowledge and attitude regarding menstruation

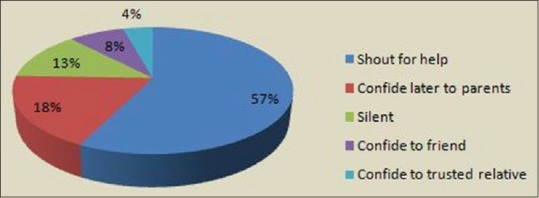

As depicted in Figure 1, when all participants were asked how they would respond to someone touching them inappropriately or exposing themselves, 57.14% (96) of them answered that they would shout for help, 18.45% (31) said that they would confide later to parents, 12.50% (21) said they would be silent, 7.74% (13) said they would confide it to a friend, and 4.17% (7) answered that they would confide it to a trusted relative.

Figure 1.

Study participants' response to inappropriate touch

Discussion

In the present study, an improvement in knowledge regarding menstruation was seen following the intervention which also included a health education session on menstruation physiology and hygiene. This highlights the effectiveness of an interventional session in reducing the knowledge gap regarding menstruation among the study participants. Frank and Williams[13] conducted a similar descriptive study of 106 fifth-, sixth-, and seventh-grade girls to determine their attitudes toward menarche. Attitudes of affirmation and worry were examined including whether the participants had talked with their mother or a close friend or seen a video on menstruation.

In the present study, health educational intervention in areas of physiological changes in puberty in both boys and girls was found to be an effective tool as it also helped in initiating in depth discussions with the girls where they could interact freely and ask questions which they would not be able to ask their parents.

More than 50% of mothers of study participants were homemakers. This fact was taken into consideration during the sessions on gender and gender stereotyping of duties both in the house and outside; and importance of both boys and girls engaging in household duties was highlighted and acknowledged by almost all participants. Early childhood experiences have been shown to influence men's adult attitudes and practices, also emphasizing the need for programs and policies to promote equitable care giving.[14]

During the session on “violence and labeling,” many participants admitted indulging in labeling and not being aware that labeling someone is also a part of violence. During the discussion on “whether menstrual blood is dirty and purifies the body,” 96.2% of girls responded in the affirmative and postintervention an attitudinal change was seen in 34% of girls in response to the same question.

The baseline/preintervention GE scores are higher for girls as compared to the boys. This is consistent with other studies.[15] However, other studies examining the complexities of gender equity and power and health also found that in many circumstances women themselves had more gender inequitable views than men on all gender attitude scales.[16,17] This highlights the areas for further qualitative research in the field of gender and violence. As these norms are internalized at an early age, in countries such as India, more attitude transformational interventions with adolescents are required to sensitize them on gender equity. Active involvement of teachers and parents through workshops, group discussions, etc., can be an effective strategy to introduce gender equality and nonviolence to children both at home and at school from an early age. Similar studies have stressed that future interventions should emphasize work with both men and boys and women and girls to change social norms on gender relations, and need to appropriately accommodate the differences between men and women in the design of programs.[12,18,19,20]

Responses to “how would you react if someone would touch you inappropriately” [Figure 1] differed and nearly 20% of participants said they would be silent/confide in a friend. The knowledge gap in identifying abuse and importance of asserting themselves was addressed in the session “my body”. Furthermore, this finding identifies an imperative area for further qualitative research and on the importance of assertiveness training for children and adolescents on how to say “no” to sexual abuse.

The increase in GE scores of postintervention is also seen to be more in girls. The outcome variables demonstrate that the greatest changes were seen more around questions related to appropriate roles for women and men and girls and boys. There was also increased support for a higher age at marriage for girls, greater male involvement in household work, increased opposition to gender discrimination. The difference in the mean scores for boys and girls, pre- and post-intervention is highly significant (P < 0.001), the change in scores was seen more in girls as compared to boys. This finding is consistent with other research that shows GE attitudes to be an effective methodology for bringing about attitudinal and behavioral changes.[12,21] In the present study, a single-mixed method intervention was highly effective in changing attitudes related to gender equity. This is consistent with studies which showed that attitudes toward gender and sexuality as reported behavior in relationships often changed.[12,21]

In a similar study, De Meyer et al.[22] studied the strong link between gender equality and sexual health. Their cross-sectional study with young people in Bolivia and Ecuador reveals that more egalitarian gender attitudes are related to higher current use of contraceptives within the couple, more positive experiences and ideas about sexual intercourse, and better communication about sexuality with the partner among sexually active and sexually nonactive adolescents.

Goicolea et al.[23] investigate how young men understand intimate partner violence from the Ecuadorian context. The main finding is that the young men take a stance in which they condemn violence, whereas at the same time, they do not really reject sexism. In another study from Southern Spain, Marcos Marcos et al.[24] provide insights into constructions of masculinities that are dependent on collective practices and performative acts which have a bearing on health behavior and gender equality.

In a similar study, Sherrow et al.[25] concluded that young men are receptive to small group formats that encourage active participation and focus on sensitive sexual health issues; and young men are interested in gaining a greater understanding of female attitudes and expectations regarding relationships with men.

MacPherson et al.[26] presented a critical overview of gender equity and SRH in Eastern and Southern Africa. They concluded that SRH is central to gender equity in health in the region and that interventions to improve it have to be enacted not only within the health system but also outside the system.

In a recent study, Das et al.[27] examined the relationship among adolescent males' gender attitudes, attitudes condoning violence against women, exposure to family and community violence, and violence perpetration against peers and girls. They found that more equitable gender attitudes were associated with significantly less likelihood of sexual violence perpetration. It concluded that promoting equitable gender attitudes may be an important modifiable factor in preventing violence against women and girls, especially among boys who have been exposed to violence.

A systematic review by Barker et al.[4] confirmed that reasonably well-designed programs and interventions with men and boys can produce short-term change in attitudes and behavior and the programs show that the evidence of being gender-transformative seems to show more success in changing behavior among men and boys.

Limitations of the study

The present study did not involve long-term (1 year later) follow-up of participants for reinforcing and reassessment of principles of gender equity and violence among them. Involvement/sensitization of parents of the school children in separately designed sessions would have been more effective in helping students to sustain the practice of gender equity in their current and future lives.

Conclusion

The results of the present mixed methods' study support promotion of education as a strategy for initiating a dialog on gender equity and violence within a school setting. Schools can provide an effective setting for initiating dialog/interventions on gender, SRH communication, and violence with adolescents; both boys and girls. This can have far flung implications on their lives and those of their families resulting in positive behavioral and health outcomes for all.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank school authorities for permission and support in conducting the study. The author would like to thank Institutional Review Board and department of Community Medicine of Apollo Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Hyderabad for their continued support.

References

- 1.WHO. Women and Gender Equity. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 02]. Available from: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/wgekn_final_report_07.pdf .

- 2.Marston C, King E. Factors that shape young people's sexual behaviour: A systematic review. Lancet. 2006;368:1581–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kishor S, Gupta K. Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment in India. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005-2006. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Engaging Men and Boys in Changing Genderbased Inequity in Health: Evidence from Programme Interventions. UN, 2002, 2008; WHO, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Campbell J. Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:132–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goicolea I, Torres MS, Edin K, Ohman A. When sex is hardly about mutual pleasure: Dominant and resistant discourses on sexuality and its consequences for young people's sexual health. Int J Sex Health. 2012;24:303–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres VM, Goicolea I, Edin K, Ohman A. 'Expanding your mind': The process of constructing gender-equitable masculinities in young Nicaraguan men participating in reproductive health or gender training programs. Glob Health Action. 2012;5:173–98. doi: 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pilgrim NA, Blum RW. Protective and risk factors associated with adolescent sexual and reproductive health in the English-speaking Caribbean: A literature review. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:5–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuo X, Lou C, Gao E, Cheng Y, Niu H, Zabin LS. Gender differences in adolescent premarital sexual permissiveness in three Asian cities: Effects of gender-role attitudes. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(3 Suppl):S18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New York: UNFPA; 2013. UNFPA. State of the world population 2013. Motherhood in Childhood: Facing the Challenge of Adolescent Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geneva: WHO; 2011. WHO. The sexual and reproductive health of younger adolescents. Research issues in developing countries. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achyut P, Bhatla N, Khandekar S, Maitra S, Verma RK. New Delhi: ICRW; 2011. Building support for gender equality among young adolescents in school: Findings from Mumbai, India. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank D, Williams T. Attitudes about menstruation among fifth-, sixth-, and seventh-grade pre-and post-menarcheal girls. J Sch Nurs. 1999;15:25–31. doi: 10.1177/105984059901500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levtov RG, Barker G, Contreras-Urbina M, Heilman B, Verma R. Men and masculinities pathways to gender-equitable men: Findings from the international men and gender equality survey in eight countries. Men Masc. 2014;17:467–501. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott J, Averbach S, Modest AM, Hacker MR, Cornish S, Spencer D, et al. An assessment of gender inequitable norms and gender-based violence in South Sudan: A community-based participatory research approach. Confl Health. 2013;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nanda G, Schuler SR, Lenzi R. The influence of gender attitudes on contraceptive use in Tanzania: New evidence using husbands' and wives' survey data. J Biosoc Sci. 2013;45:331–44. doi: 10.1017/S0021932012000855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimuna SR, Djamba YK, Ciciurkaite G, Cherukuri S. Domestic violence in India: Insights from the 2005-2006 national family health survey. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28:773–807. doi: 10.1177/0886260512455867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fulu E, Jewkes R, Roselli T, Garcia-Moreno C UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence research team. Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e187–207. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewkes R, Flood M, Lang J. From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: A conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. Lancet. 2015;385:1580–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. Gender Tool, European Strategy for Child and Adolescent Health and Development. [Last accessed on 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/76511/EuroStrat_Gender_tool.pdf .

- 21.Verma RK, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra V, Khandekar S, Barker G, Fulpagare P, et al. Challenging and changing gender attitudes among young men in Mumbai, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14:135–43. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Meyer S, Jaruseviciene L, Zaborskis A, Decat P, Vega B, Cordova K, et al. A cross-sectional study on attitudes toward gender equality, sexual behavior, positive sexual experiences, and communication about sex among sexually active and non-sexually active adolescents in Bolivia and Ecuador. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24089. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goicolea I, Öhman A, Salazar Torres M, Morrás I, Edin K. Condemning violence without rejecting sexism. Exploring how young men understand intimate partner violence in Ecuador? Glob Health Action. 2012;5:1–12. doi: 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcos Marcos J, Avilés NR, del Río Lozano M, Cuadros JP, García Calvente Mdel M. Performing masculinity, influencing health: A qualitative mixed-methods study of young Spanish men. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:21134. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.21134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherrow G, Ruby T, Braverman PK, Bartle N, Gibson S, Hock-Long L. Man2Man: A promising approach to addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of young men. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35:215–9. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.214.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacPherson EE, Richards E, Namakhoma I, Theobald S. Gender equity and sexual and reproductive health in Eastern and Southern Africa: A critical overview of the literature. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23717. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das M, Ghosh S, Verma R, O'Connor B, Fewer S, Virata MC, et al. Gender attitudes and violence among urban adolescent boys in India. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2014;19:99–112. [Google Scholar]