Abstract

Introduction:

Menstruation is a milestone event in a girl's life and the beginning of reproductive life. Lack of knowledge and poor sanitary practices during menstruation has been associated with serious ill-health ranging from genital tract infections, urinary tract infections, and bad odor.

Aim:

This study aims to explore the knowledge, attitude, and practices about menstrual hygiene and perceived reproductive morbidity among adolescent school girls in Puducherry.

Materials and Methods:

A school based cross-sectional study was conducted from June 2015 to July 2015 in Puducherry among 242 adolescent school girls in the age group of 12–18 years using multistage random sampling technique. Data were collected using a predesigned pretested, structured proforma by personal interview method after having informed written consent.

Results:

The mean age for menarche was 12.99 ± 0.9 years; 51.7% of respondents were not aware of menstruation before attaining menarche; 71.5% and 61.2% were not known about the cause and source of the menstrual bleeding, respectively; 78.1% used only sanitary pads whereas 21.9% used both old clothes and sanitary pads as the absorbents. Unsatisfactory cleaning of the external genitalia was practiced by 12% of respondents. Higher prevalence of dysmenorrhea (82.2%) was mentioned by the respondents; 25.2% reported excessive genital discharge. Statistically significant association was found between perceived reproductive morbidity and poor menstrual hygiene practices. About 88.4% of the study population reported any one of the reproductive morbidity, and only 37.4% sought for medical treatment from a health facility.

Conclusion:

The present study has underscored the necessity of adolescent girls to have adequate and precise knowledge about menstruation before menarche. Proper menstrual hygiene practices which could be imparted through appropriate interventions at earlier stages of life can prevent the girls and women from suffering reproductive morbidities.

Keywords: Adolescent school girls, menstrual hygiene, menstruation, reproductive morbidity

Introduction

Menstruation is a milestone event in a girl's life and the beginning of reproductive life. Hence, all aspects of menstruation need to be understood by adolescent girls. Large number of girls has scanty knowledge about menstruation until their first experience because menstruation is something that is not frequently talked off in homes.[1]a Better understanding of the good menstrual hygiene is crucial for the education, health, and dignity of girls and women. Being an important sanitation issue which has long been in the closet, still, there is a long-standing need to openly discuss it. Most of the time adolescent girls are unprepared – in terms of knowledge, skills, and attitudes for managing the menstrual cycle.[2] This lack of knowledge and poor personal sanitary practices during menstruation has been associated with serious ill-health ranging from genital tract infections, urinary tract infections, and bad odor.[3,4,5]

Unhealthy menstrual practices are not washing genitalia regularly, using unclean cloth, etc. Learning about menstrual hygiene forms a vital aspect of health education among menstruating women to avoid future long-term ill effects of poor menstrual hygiene practices leading to premature births, stillbirths, miscarriages, infertility problems, toxic shock syndrome, carcinoma cervix as a complication of recurrent reproductive tract infections.[6] There is the difference in prior awareness about menstruation and menstrual hygiene and their relation with reproductive health among rural and urban adolescent girls.[7]

Research indicates that a vast information gap exists among adolescent girls regarding prior awareness about menstruation and menstrual hygiene which do have an impact on the practices during menstruation[1] and the associated gynecological morbidities. Hence, the present study was done to estimate the magnitude of perceived gynecological morbidities as well as to find out the relation between the knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) about menstruation.

With this background, the current study was conducted to explore the KAP about menstrual hygiene and the magnitude of perceived reproductive morbidity among adolescent school girls in Puducherry.

Materials and Methods

This institution based observational descriptive study, cross-sectional in design was carried out among the school going adolescent girls of both urban and rural government schools of Puducherry for 2 months from June 2015 to July 2015. The inclusion criteria were adolescent school girls studying in class 9th–12th standard; who have attained menarche. Adolescent school girls and/or the parents who refused to give consent were excluded from the study. Considering the prevalence of sanitary pad usage among school going urban and rural adolescent girls as 70%,[7] with α = 10%, β = 20%, error of margin = 5%, the minimum sample size was found to be 227 using the formula, n = P × (100 − P) × z2/d2 where P is the anticipated prevalence; d is the desired precision; z is the standard normal distribution for the desired confidence level.[7]

Multistage random sampling procedure was used to select the desired sample size. First of all, two commune (Oulgaret and Bahour) was chosen out of seven commune in district Puducherry by random sampling. Then, a list of all higher secondary government (co-ed and girls) school was made for Oulgaret and Bahour commune separately. Finally, one school was randomly selected from the Oulgaret commune and one from Bahour commune. Consent from the directorate of school education and from the head of each school was taken before conducting the study. A consent form was given to each student who was involved in the study and was asked get it signed from their parents. All the eligible students in the selected school who were meeting the criteria were considered for the study. Following that data were collected by interview method using a predesigned pretested, structured proforma. The proforma was used to collect data regarding their socio-demographic profile, symptoms and imposed restrictions, knowledge, and perceptions regarding menstruation, perception regarding advantages and disadvantages of sanitary napkins, hygiene during menstruation, and reproductive morbidities. confidentiality was maintained for the data collected throughout the study.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered using EpiData version 3.1 (Informer Technologies, Inc., Roseau Valley, DM). Simple percentages, proportions, mean and standard deviation were used for describing the results of the study and Chi-square test was used to find the association. Data were analyzed using EpiData analysis V2.2.2.183 and MS Excel 2013. The value of P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

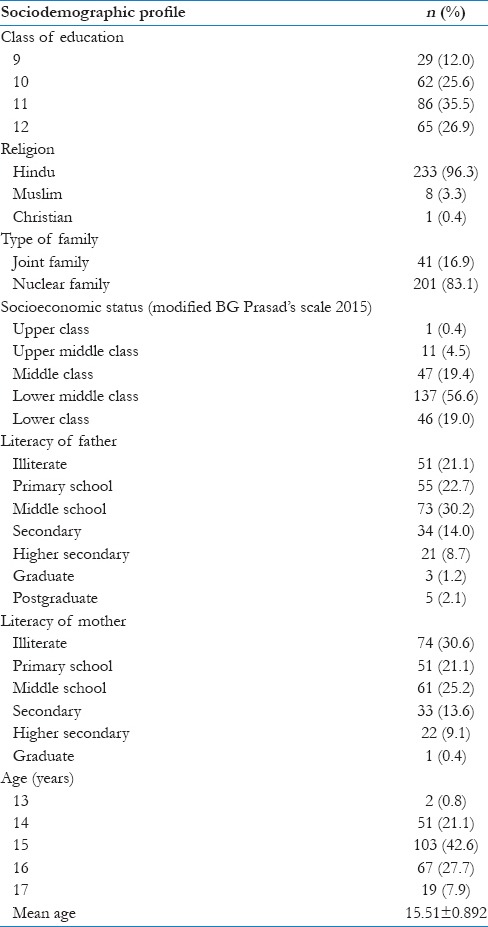

Table 1 demonstrates that a total of 242 adolescent girls studying in classes 9th–12th were involved in the present study. Most of the girls were in the age of 15 years (42.6%) followed by 16 years (27.7%); about 96.3% of the girls were Hindus; 83.1% were from nuclear families. The majority (56.6%) of the girls were from lower middle-class families followed by the middle class (19.4%) as per modified BG Prasad scale 2015. Most of the fathers were having middle school education (30.2%), whereas most of the mothers were illiterates (30.6%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of the study participants (n=242)

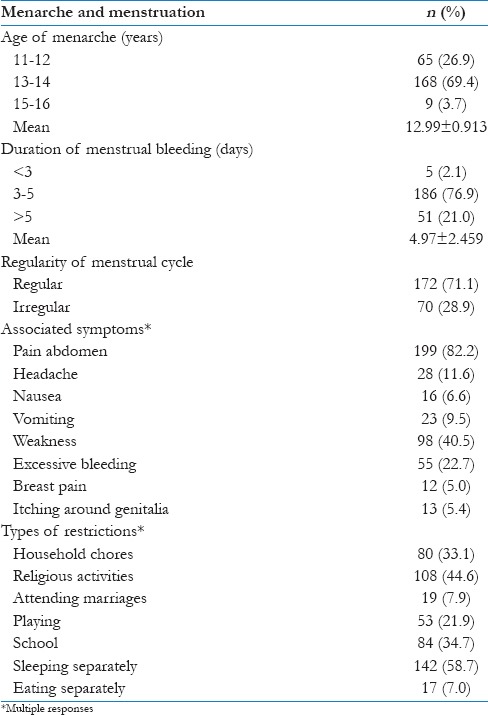

Table 2 shows that majority (71.1%) of girls had reported having a regular menstrual cycle. Most of the girls (82.2%) had abdominal pain during menstruation followed by weakness (40.5%). Regarding various types of restrictions as shown in Table 2, 58.7% of girls sleep separately, 44.6% of girls were restricted to attend any religious event, 34.7% of girls did not go to school, 33.1% of girls did not carry out any household activities, 21.9% girls did not play, 7.9% of girls did not attend any marriages and 7% of girls were eating separately during the menstrual period.

Table 2.

Distribution of study population according to menstrual history (n=242)

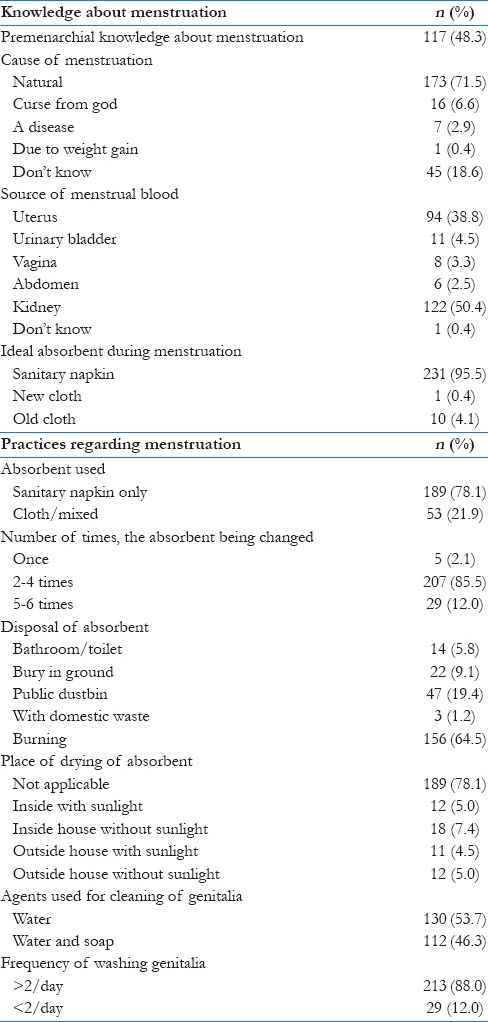

Regarding knowledge, about 71.5% of respondents knew that the menstruation is a natural physiological process and only 38.8% knew that the source of menstrual blood is uterus. The sanitary pad was mentioned as ideal absorbent by 95.5% of the study population. Unsatisfactory cleanliness of external genitalia was reported (frequency of washing external genitalia was < 2/day) by 29 (12%) girls [Table 3].

Table 3.

Knowledge and practices of the adolescent girls regarding menstruation (n=242)

So far practices were concerned, 78.1% girls were using sanitary napkin whereas 21.9% girls were either cloth or mixed users during menstruation. The majority (85.5%) were changing the absorbent 2–4 times during the menstruation. Most of the girls were disposing the absorbent by burning (64.5%) followed by public dustbin (19.4%). Among cloth users, many were drying it inside the house without sunlight (34%). Majority washed their genitalia using only water (53.7%) during menstruation.

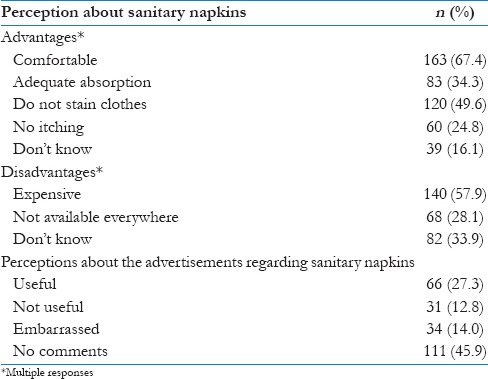

Table 4 shows that 67.4% of respondent girls perceived that on using sanitary pads they felt comfortable, 49.6% perceived that it would not stain clothes, 34.3% felt that it absorbed adequately whereas 24.8% felt that there was no itching with its use. On the other hand, 57.9% adolescent girls perceived it to be expensive, and 28.1% felt that it was not available everywhere. 27.3% adolescent girls felt that the advertisement about sanitary napkins was useful while 14% felt it embarrassing and 12.8% as not useful.

Table 4.

Perception regarding advantages and disadvantages of sanitary napkins (n=242)

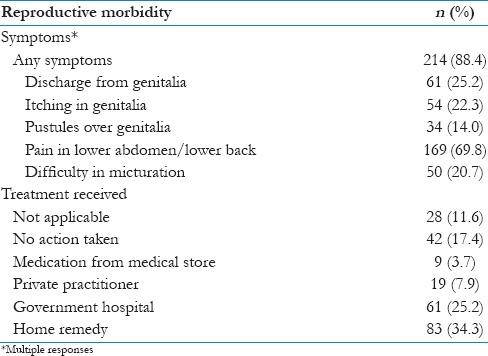

Astonishingly, a high proportion of respondents reported having at least one reproductive tract problem (88.4%). The commonly reported reproductive morbidity were symptoms of lower abdominal/lower back pain (69.8%), discharge from genitalia (25.2%), itching from genitalia (22.3%), difficulty in micturition (20.7%), and pustules over genitalia (14%) [Table 5]. Out of the 214 (88.4%) adolescent girls who perceived any reproductive tract morbidity only 89 (41.6%) received treatment for these health problems. Overall, 80 (37.4%) of respondents reported for seeking treatment from any registered medical practitioner.

Table 5.

Distribution of study population according to perceived reproductive morbidity and treatment received

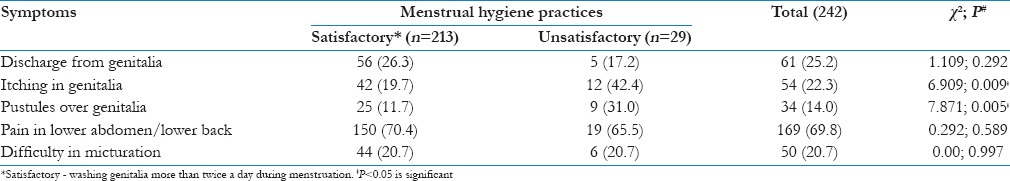

Some of the symptoms suggestive of reproductive tract infections were observed to be more common among the girls who were having unsatisfactory menstrual hygiene practices, and this difference was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) for itching in genitalia and pustules over genitalia [Table 6].

Table 6.

Association between perceived reproductive morbidity and menstrual hygiene practices (n=242)

Discussion

In this study, majority of adolescent girls 168 (69.4%) attained menarche at the age of 13–14 years; mean age of menarche was 12.99 years; and 76.7% had 3–5 days of menstrual flow; which was similar to the findings by Balasubramanian[8] and Juyal et al.[2]

In this study, only 48.3% of the study population had knowledge regarding menstruation before menarche which was almost corroborative with the findings by Verma et al. where 58.3% girls had reported having prior knowledge about menstruation.[9] More than half of the adolescent girls were unaware about menstruation before menarche. Ideally, every girl child must be aware of menstruation before menarche which will have a long role in maintaining the menstrual hygiene and preventing its related morbidities.

About 71.5% of the girls believed that menstruation is a natural phenomenon which was fairly similar to the observation by Verma et al. where 85.83% of girls believed it to be a natural phenomenon.[9] It was evident that a majority of girls in the study (61.2%) were not aware of the correct source of menstrual bleeding which was in line to a study by Pundkar et al. where 70.71% girls did not know the source.[10] The above findings may be due to low literacy level among mothers and absence of menstrual hygiene related education programs in schools.

In India, different communities follow a different type of restrictions during menstruation. In our study, girls were asked to sleep separately (58.7%) which was the most common restriction, followed by restricting religious activities (44.6%). In contrast, Verma et al. recorded playing and going outside home were the most common restrictions.[9]

This study showed that majority of the girls use only sanitary napkin (78.1%) as menstrual absorbent rather than cloth pieces. Only 21.9% girls used both cloth and sanitary napkins. This was in contrary to the study conducted in West Bengal by Dasgupta and Sarkar[3] and in Tamil Nadu by Balamurugan et al.[11] where the majority of girls (>50%) preferred using clothes to sanitary napkin. This could be due to the availability of napkins in adolescent clinics conducted in Primary health centers at free of cost in Puducherry and wide publicity through mass media.

Water and soap (63%) were the most common agents used for cleaning genitalia in a study conducted by Pundkar et al.[10] whereas in the present study the most common agent was only water (53.7%) followed by soap and water (46.3%). Pundkar et al.[10] also showed that satisfactory cleaning of external genitalia was reported by 97% of girls which was almost similar to our study where it was reported by 88% of girls. In the present study, the commonly practiced method of disposing the absorbent was burning similar to the findings by another author.[10]

The prevalence of dysmenorrhea in our study was found to be 82.2% whereas it ranged from 60% to 93%[12] in Multan city, Pakistan and 62%–65% in India as reported from East Delhi[13] and Karnataka.[14] Even in India, a study conducted among young girls in Indore by Kural et al. had observed 84.2% prevalence of dysmenorrhea.[15]

In our study, excessive discharge from genitalia (probable respiratory tract infections) had been reported by 25.2% of adolescent girls, itching in genitalia by 22.3% and difficulty in micturition by 20.7% girls. These were almost similar to the findings reported by Juyal et al.[2] (19% vaginal discharge and 7.9% itching in genitalia) and Ram et al. (12% burning sensation).[16] This is due to the fact that discussing menstrual hygiene is considered as taboo subject in India[2] which hinders women and girls from getting treatment on time.

Out of 214 girls who reported any one of the reproductive morbidity, only 80 (37.4%) of girls sought medical treatment from a health facility. This is similar to a study conducted at Nagpur by Kulkarni and Durge where girls seeking and not seeking health care was 33.67% and 62.33%, respectively.[17] In spite of a high prevalence of reproductive morbidities among adolescent girls, there is a low treatment seeking behavior from health care.

Conclusion

To conclude, the present study has underscored the necessity of adolescent girls to have adequate and precise knowledge about menstruation before menarche. They should also be taught about its relationship with their reproductive health. Menstrual pain is a very common problem reported by majority of adolescent girls which points out the need for suitable intervention through lifestyle modification. Reproductive tract morbidities which can devastate a women's life is directly linked with poor menstrual hygiene practices. The girls should be made aware of the facts of menstruation and proper hygienic practices through mass media, school curriculum and school teacher, health personnel and above all, well-informed parents. Health camps in schools need to be conducted to treat the girls suffering from reproductive tract morbidities.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are very much thankful to ICMR STS Reference ID: 2015-02507.

References

- 1.Patle RA, Kubde SS. Comparative study on menstrual hygiene in rural and urban adolescent. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3:129–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juyal R, Kandpal SD, Semwal J. Menstrual hygiene and reproductive morbidity in adolescent girls in Dehradun, India. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 19];Banglad J Med Sci. 2014 13:170–4. Available from: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.3329/bjms.v13i2.14257 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dasgupta A, Sarkar M. Menstrual hygiene: How hygienic is the adolescent girl? Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:77–80. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.40872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mudey AB, Keshwarni N, Mudey GA, Goyal RC. A cross-sectional study on the awareness regarding safe and hygienic practices amongst school going adolescent girls in the rural areas of Wardha District, India. Glob J Health Sci. 2010;2:225–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatia JC, Cleland J. Self-reported symptoms of gynecological morbidity and their treatment in South India. Stud Fam Plann. 1995;26:203–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bathija GV, Bant DD, Itagimath SR. Study on usage of woman hygiene kit among menstruating age group in field practice area of KIMS, Hubli. Int J Biomed Res. 2013;4:95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamath R, Ghosh D, Lena A, Chandrasekaran V. A study on knowledge and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among rural and urban adolescent girls in Udupi Taluk, Manipal, India. Glob J Med Public Health. 2013;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balasubramanian P. Health needs of poor unmarried adolescent girls – A community based study in rural Tamil Nadu. Indian J Popul Educ. 2005;2:18–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma P, Ahmad S, Srivastava RK. Knowledge and practices about menstrual hygiene among higher secondary school girls. Indian J Community Health. 2013;25:265–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pundkar RD, Zambare MB, Baride JP. The knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in one of the municipal corporation school of Ahmednagar. VIMS Health Sci J. 2014;1:118–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balamurugan SS, Shilpa S, Shaji S. A community based study on menstrual hygiene among reproductive age group women in a rural area, Tamil Nadu. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci. 2014;3:83–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali S, Sultana H, Sayyada I, Parveen N. Primary dysmenorrhoea in adolescence. Med Forum Mon. 2009;20:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nair P, Grover VL, Kannan AT. Awareness and practices of menstruation and pubertal changes amongst unmarried female adolescents in a rural area of East Delhi. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:156–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.George NS, Priyadarshini S, Shetty S. Dysmenorrhoea among adolescent girls-characteristics and symptoms experienced during menstruation. Nitte Univ J Health Sci. 2014;4:2249–7110. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kural M, Noor NN, Pandit D, Joshi T, Patil A. Menstrual characteristics and prevalence of dysmenorrhea in college going girls. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:426–31. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.161345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ram R, Bhattacharya SK, Bhattacharya K, Baur B, Sarkar T, Bhattacharya A, et al. Reproductive tract infection among female adolescents. Indian J Community Med. 2006;31:32–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulkarni MV, Durge PM. Reproductive health morbidities among adolescent girls: Breaking the silence. Ethno Med. 2011;5:165–8. [Google Scholar]