Abstract

More than 30 proteins form amyloid in humans, most of them outside of the brain. Deposition of amyloid in extracerebral tissues is very common and seems inevitable for an aging person. Most deposits are localized, small, and probably without consequence, but in some instances, they are associated with diseases such as type 2 diabetes. Other extracerebral amyloidoses are systemic, with life-threatening effects on the heart, kidneys, and other organs. Here, we review how amyloid may spread through seeding and whether transmission of amyloid diseases may occur between humans. We also discuss whether cross-seeding is important in the development of amyloidosis, focusing specifically on the amyloid proteins AA, transthyretin, and islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP).

The types of extracerebral amyloid constitute a large and heterogeneous group that includes small, local, and seemingly innocent deposits as well as severe and usually lethal systemic types. This group also includes a number of local amyloid types that are, or are suspected to be, important in the pathogenesis of specific diseases. A total of 31 different proteins have been identified as amyloid-forming in humans (Sipe et al. 2014). Of these, two (insulin and enfurvitide) cause iatrogenic amyloid, and 14 are associated with systemic diseases. At least three systemic (ATTR, ACys, and ABri; for nomenclature, see Sipe et al. 2014 and Tables 1 and 2) and two extracerebral (AL and medin) localized amyloidoses can have intracerebral deposits, usually confined to meninges and blood vessels. More biochemical amyloid forms will likely be defined in the future.

Table 1.

The 14 proteins that constitute fibrils in systemic amyloidoses

| Designation | Parent protein | Associated condition |

|---|---|---|

| AL | Immunoglobulin light chain | Plasma cell dyscrasia |

| Immunoglobulin light chain (mutant) | Hereditary | |

| AH | Immunoglobulin heavy chain | Plasma cell dyscrasia |

| AA | Serum amyloid A (SAA) | Prolonged SAA expression |

| ATTR | Transthyretin (mutant) | Hereditary |

| Transthyretin (wild-type) | Aging | |

| Aβ2M | β-2 microglobulin (wild-type) | Hemodialysis |

| β-2 microglobulin (mutant) | Hereditary | |

| AApoAI | Apolipoprotein A-I (mutant) | Hereditary |

| AApoAII | Apolipoprotein A-II (mutant) | Hereditary |

| AApoAIV | Apolipoprotein A-IV (wild-type) | Aging |

| AGel | Gelsolin (mutant) | Hereditary |

| ALys | Lysozyme (mutant) | Hereditary |

| ALECT2 | Leucocyte chemotactic factor-2 | Unknown |

| AFib | Fibrinogen α-chain (mutant) | Hereditary |

| ACys | Cystatin C (mutant) | Hereditary |

| ABri | ABriPP | Hereditary |

Three of the amyloid forms (ATTR, ABri, and ACys) have or may have intracerebral deposits.

Table 2.

Biochemically characterized localized extracerebral amyloid forms in humans

| Designation | Parent protein | Target organ | Associated condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| AL | Immunoglobulin light chain | Varying | Localized plasma cell clone |

| AH | Immunoglobulin heavy chain | Varying | Localized plasma cell clone |

| ACal | Calcitonin | Tumor | Thyroid C-cell neoplasm |

| AANF | Atrial natriuretic factor | Cardiac atria | Aging |

| APro | Prolactin | Pituitary | Aging |

| Tumor | Pituitary neoplasm | ||

| AIAPP | Islet amyloid polypeptide | Islets | Aging |

| Islets | Type 2 diabetes | ||

| Tumor | β-cell neoplasm | ||

| AIns | Insulin | Skin | Iatrogenic |

| ASPC | Surfactant protein | Lung | Mutation |

| AGal7 | Galectin-7 | Skin | Unknown |

| ACor | Corneodesmosin | Skin | Mutation |

| AMed | Lactadherin | Arterial media | Aging |

| AKer | Keratoepithelin | Cornea | Mutation |

| ALac | Lactoferrin | Cornea | Unknown |

| AOAAP | Odontogenic ameloblast-associated protein | Odontogenic tumors | Neoplasm |

| ASem1 | Semenogelin-1 | Seminal vesicles | Aging |

| AEnf | Enfurvitide | Skin | Iatrogenic |

The unifying property of systemic amyloidoses is that the fibril precursor is expressed in one or a few tissues, circulates in blood plasma, and is finally deposited as amyloid in a number of organs, except the brain usually. Only some of the proteins, shown in Table 1, are related. In vitro studies have shown that many other proteins can make up fibrils with all amyloid properties. So why does this limited number occur in vivo? Two factors may be obvious from Table 1. A large proportion of the systemic amyloidoses are hereditary, usually depending on a point mutation resulting in an amino acid substitution. This may be enough to destabilize the protein and make it prone to misfold and aggregate or, as is the case with transthyretin (TTR), make the quaternary structure less stable (McCutchen et al. 1993; Colon et al. 1996; Quintas et al. 1999). Another factor is protein concentration because nucleation and fibril formation are concentration-dependent. The pathogenesis of at least some of the systemic amyloidoses with a wild-type (WT) protein (AA, AL, and Aβ2M; for nomenclature, see Sipe et al. 2014) includes an increased plasma concentration of the parent protein. There are likely additional factors that are less well understood. Interaction with heparan sulfate (Snow et al. 1991; Elimova et al. 2009; Lindahl and Kjellén 2013) and serum amyloid P-component (Cathcart et al. 1965), present in all kinds of amyloid and also of localized type, is undoubtedly important in pathogenesis (Li et al. 2005; Bodin et al. 2010). For reviews of the systemic amyloidoses, see Merlini and Bellotti (2003), Merlini and Westermark (2004), Merlini et al. (2014), and Pinney and Hawkins (2012).

In contrast to systemic forms, fibril proteins in localized amyloidoses are usually expressed by cells close to the site of deposition. A locally high concentration of the precursor protein here is a decisive pathogenic factor. It is therefore not surprising that amyloid deposits are often seen in polypeptide-hormone secreting tissues, and four (five if insulin is included) of the human amyloid proteins characterized so far are hormones. Given the normally very high local concentrations of amyloid-prone polypeptide hormones, strong protective antiaggregation mechanisms must exist. Interestingly, a “functional amyloid” conformation has been proposed as a normal storage form for many such hormones (Maji et al. 2009). However, there must be a definitive difference between the functional amyloid conformation and amyloid fibrils because the release of stored hormones requires an immediate solubilization, which can hardly be obtained from an amyloid fibril. Under controlled conditions, Congo red does not stain normal polypeptide hormone-expressing cells (Puchtler et al. 1962; Westermark 2012).

Amyloid deposits outside the brain are common, and everyone reaching the age of 50 will likely have one or more biochemically distinct types. Most of these deposits are localized to single tissues and organs and are believed to be benign, although they may all reflect pathological processes not yet understood. Some localized extracerebral amyloid types are associated with specific diseases, and there is evidence that some of them are involved in pathogeneses, either as mature fibrils or as oligomeric aggregates. Much more has to be learned about these localized deposits. Table 2 lists the biochemically characterized human amyloid forms.

This work is not a complete overview of all extracerebral systemic and localized amyloidoses (for a review of amyloid in type 2 diabetes, see Westermark et al. 2011; Mukherjee and Soto 2017). Rather, it focuses on the possibility of amyloidosis transmission in humans and also the problem of strains and phenotypes. Cross-seeding and “cross-transmission” are also discussed. We therefore concentrate on a few types of localized and systemic amyloidoses.

AMYLOID FIBRIL STRUCTURE

The conservation of the X-ray diffraction pattern implies that the cross-β structure is generic to all amyloid fibrils. Another common feature is their protofilament substructure (Sipe et al. 2014). Protofilaments are the filamentous subunits of mature fibrils. They are often entangled, giving rise to a helically twisted and usually left-handed superstructure.

The cross-β structure forms the structural spine of the protofilaments, but relatively little is known about the atomic structure of the fibrils and specifically those fibrils that occur in a patient. Much of our current knowledge comes instead from the X-ray crystallographic analysis of peptide microcrystals and from the study of in vitro formed fibrils. These filaments may not be the same as those occurring in humans, however. For that reason, the Nomenclature Committee of the International Society of Amyloidosis recommends in vitro formed filaments to be referred to as “amyloid-like” (Sipe et al. 2014), at least until their structural identity to in vivo fibrils has been firmly established. Different principles of structuring amyloid-like fibrils have been described, including filaments consisting of β-arches, peptide dimers, and β-solenoid structures (Toyama and Weissman 2011). In the case of peptide microcrystals, it was found that they consist of pairs of two cross-β sheets that are packed up against one another in a self-complementary fashion. This assembly has been termed a (steric) zipper (Sawaya et al. 2007; Eisenberg and Jucker 2012) and may exist as such within full-scale amyloid or amyloid-like fibrils as well.

SEEDING AND CROSS-SEEDING

The cross-β architecture defines the sets of interactions that are important for fibril growth. Growth in the direction of the main fibril axis occurs by extension of the cross-β sheet and involves backbone hydrogen bonds as well as side-chain interactions between the hydrogen-bonded peptides. Growth in the orthogonal direction, in contrast, depends almost exclusively on side-chain interactions and occurs between peptides that are not present in the same β-sheet. As amyloid fibril structures are significantly anisotropic, it can be assumed that the interactions occurring within the same sheet are considerably more favorable than those occurring between sheets. Hence, cross-β structures tend to form filaments.

The kinetics of this process are associated with an S-shaped growth curve and a discernible lag phase (Jarrett and Lansbury 1993; Harper and Lansbury 1997). Similar growth curves are common to other protein filaments and occur in the fibrillation of sickle cell hemoglobin or bacterial flagellin, for example (Oosawa and Asakura 1975; Eaton and Hofrichter 1990). These curves imply that fibrils form by a nucleation polymerization mechanism, in which an initial, slow, and/or energetically unfavorable step leads to the formation of a nucleus that subsequently enables the rapid and energetically favorable addition of further protomers and the outgrowth into a fibril.

Mathematical modeling of in vitro fibrillation kinetics data show the contributions of primary and secondary nucleation mechanisms (Xue et al. 2008; Knowles et al. 2009). Primary nucleation (or homogeneous nucleation) is the de novo formation of a nucleus from the fibril-forming protomers. For example, monomeric fibril proteins self-assemble into a fibril fragment, which then seeds the formation of a fibril. Secondary nucleation mechanisms can involve different reactions, such as fibril fragmentation and heterogeneous nucleation mechanisms. Fibril fragmentation accelerates the polymerization reaction, as it increases the number of sites in a sample that protomers can bind to. Heterogeneous nucleation means that the lateral surface of the fibril (rather than the tip) templates the formation of a fibril fragment, which then enables the outgrowth of a new fibril. Secondary nucleation thus differs from primary nucleation, as it depends on the initial presence of at least some fibrils.

The effect of seeding can be examined macroscopically, as addition of preformed fibrils reduces or eliminates any observable lag phase (Harper and Lansbury 1997). Interestingly, there are possibilities to accelerate fibril formation by cross-seeding—that is, fibrils from one protein may seed the formation of fibrils from another protein. If one protein extends a fibril fragment from another protein, this leads to the formation of a mixed fibril consisting of two proteins. A biophysical explanation for the relevance of cross-seeding and the formation of mixed fibrils is provided by the significant structural similarities of amyloid fibrils in terms of their generic cross-β structure. Although it seems plausible that this structure is able to accommodate different polypeptide sequences, the combination of different protein sequences in the cross-β structure can lead to noncomplementarities among the different amino acid sequences. As a consequence, the formation of mixed fibrils is rare, specifically in vivo, and the limited molecular complementarity of different polypeptide chains may underlie the species barrier present when fibrils from a different species or protein are used as seeds. Nevertheless, cross-seeding does occur, at least experimentally.

ASPECTS ON TRANSMISSION OF SYSTEMIC AMYLOIDOSES AND ON PHENOTYPES

AA Amyloidosis

AA amyloidosis (in the past called secondary amyloidosis) is a systemic disease in which amyloid deposits appear in virtually all organs except for the brain. The disease is ultimately lethal because of renal engagement. The fibril protein AA is derived from its precursor, serum amyloid A (SAA), by proteolytic cleavage by which a C-terminal segment is removed, leaving the α-helix-rich N-terminal lipid-binding segment to form fibrils (Lu et al. 2014). This part is flexible and converted into a β-sheet-rich segment during fibrillogenesis. Heparan sulfate may be involved in this conversion (Elimova et al. 2009).

AA amyloidosis is a consequence of long-standing severe inflammatory conditions, leading to persistent overproduction of acute phase proteins including SAA. AA amyloidosis is the most common systemic form. In a study of autopsy protocols from Uppsala, Sweden (1899–1902), 30% of subjects with tuberculosis also suffered from amyloidosis (Westermark et al. 1984). For a recent review on AA amyloidosis, see Westermark et al. (2015).

Human AA amyloidosis rarely occurs unless there has been a persistently high concentration of SAA in the plasma for a long time. The time span between the start of inflammatory disease and the development of amyloidosis is usually at least 10 yr. In the past, when tuberculosis and other chronic infections were the most common causes of AA amyloidosis, the time span was likely shorter. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear but may depend on the level of SAA concentration. With reference to the finding that bacterial curli can initiate experimental murine amyloidosis by cross-seeding (Johan et al. 1998), it is tempting to speculate that bacterial structures could have been involved in the pathogenesis of AA amyloidosis in conjunction with infectious diseases. This could explain the surprisingly high prevalence of AA amyloidosis in certain areas where infectious diseases are common (McAdam et al. 1996).

AA Amyloidosis Is the Primary Example of Transmissible Amyloidosis (Prion Disorders Excluded)

A large number of early experiments showed that AA amyloidosis is transmissible in mice (Mus musculus). When extracts of organs from amyloidotic animals were injected intravenously into recipient animals that were in an inflamed state by various agents (Escherichia coli, casein, Freund’s complete adjuvant, silver nitrate, etc.), the time to develop amyloidosis was dramatically reduced (Werdelin and Ranløv 1966; Hardt 1971; Hardt and Ranløv 1976; Axelrad et al. 1982). It has also been shown that AA amyloidosis can be transmitted similarly in other species, such as hamsters (Hol et al. 1986), mink (Mustela vison) (Sørby et al. 2008), domestic hen (Gallus gallus domesticus) (Murakami et al. 2013), and Pekin duck (Anas platyrhynchos domestica) (Benditt 1976). The elusive agent was often named amyloid enhancing factor (AEF). Trials for purification were fruitless, and it was suggested that AEF might be associated with fibrils or perhaps part of the fibrils themselves (Niewold et al. 1987). It was finally shown that fibrils made from synthetic peptides exert AEF activity, most likely by seeding (Ganowiak et al. 1994; Johan et al. 1998; Westermark et al. 2009). The exact nature has not been solved at the molecular level, and unlike prions (Wille et al. 1996), there are no studies showing a separation of infectivity from amyloid properties. It should be emphasized that AEF has no effect in a normal, noninflamed animal with low plasma SAA concentration. In addition to AA amyloidosis, apolipoprotein AII amyloidosis is transmissible in mice (Xing et al. 2001; Korenaga et al. 2004), but this disease lacks a human WT counterpart.

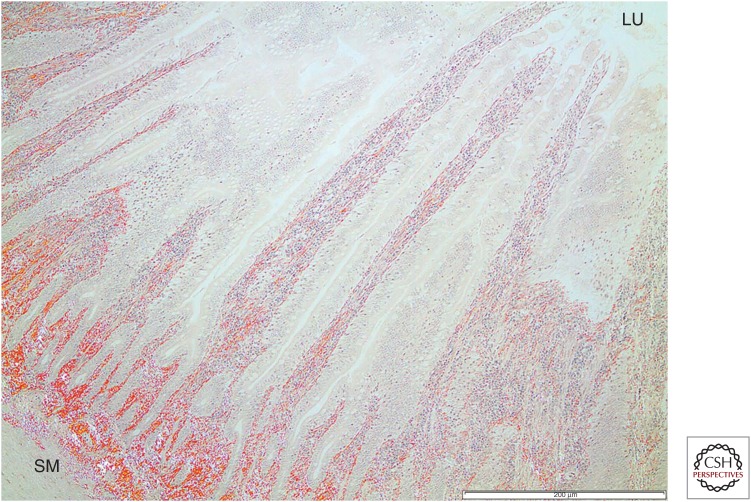

From these findings, it seems clear that AA amyloidosis can be transmitted from one individual to another if (1) the seed can reach the target tissue and (2) the amyloid protein precursor (substrate) is present in a high enough concentration. There is some indirect evidence that AA amyloidosis spreads among animals in the wild through seeding. The spreading among captive cheetah resembles a natural situation (Zhang et al. 2008). A high prevalence of AA amyloidosis among island foxes (Urocyon littoralis) may indicate transmission, but there are other possibilities because their SAA structure is unique (Gaffney et al. 2014). The same may be true for a high prevalence of the disease in Swedish herring gulls (Larus argentatus) (D Jansson, T Mörner, P Westermark, et al., unpubl.). AA amyloidosis likely spreads via feces in which fibrils are present. For instance, in gulls, amyloid deposits are often seen close to the lumen in the intestinal mucosa (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Tissue from the intestinal wall of a herring gull with AA amyloidosis stained with Congo red. Amyloid deposits (red) are seen throughout the layers and reach from the submucosal layer (SM) to the innermost part, the intestinal lumen (LU). Scale bar, 200 µm.

The site where initial amyloid fibrils form in AA (and apoAII) amyloidosis is the spleen, at least in experimental mammals. In most studies, seeds are administered intravenously, and the perifollicular area in the spleen is a site where particles are filtered and degraded. SAA, circulating in the plasma and bound to high-density lipoprotein (HDL), is released from fat particles and recruited to the seed as free SAA monomers. The amount of free SAA in the plasma is very low (Kisilevsky and Manley 2012) but cannot be neglected. Exactly how SAA is recruited to amyloid is not understood. The mechanism may include the dissociation of SAA from HDL by competitive binding to heparan sulfate (Noborn et al. 2012; Lu et al. 2014), which is highly expressed perifollicularly in the spleen at inflammation (Kisilevsky and Manley 2012).

Protein AA is missing a variably long segment of the C terminus of SAA, but whether cleavage occurs before or after fibrillation is unknown (Magy et al. 2007; Ishii et al. 2013). In humans, the split point varies and gives rise to AA proteins between 44 and about 100 residues in length. There is an association between AA protein length and amyloid deposition pattern (for review, see Westermark and Westermark 2010).

AEF seeds can also be efficiently transmitted orally (Lundmark et al. 2002), which is likely the route by which AA amyloidosis was initiated in captive cheetah (Zhang et al. 2008). Small AA aggregates, or perhaps misfolded monomers, are likely taken up from the gastrointestinal tract and transported via plasma or cells to the spleen. It is possible that AA aggregates are transported in a similar way as prions, through specialized epithelial cells over Peyer’s plaques (Safar et al. 2008) and perhaps engulfed by circulating macrophages, which can transport the seed to the spleen (Sponarova et al. 2008). At present, there is no evidence that the development of AA amyloidosis is different when it begins from a seed compared with inflammation. However, why does AA amyloidosis start perifollicularly in the spleen and not elsewhere, even when a seed is not available? It could be that this area, important in clearance, accumulates various kinds of misfolded protein aggregates, including SAA. Macrophages are involved both in generation and resolution of amyloid. The outer rim of the spleen’s white-pulp region contains marginal zone macrophages (MZM) and metallophilic marginal zone macrophages (MMZM). Induction of AA amyloid by intravenous injection of AEF and a concomitant injection of 1% silver nitrate results in an almost complete eradication of MZM as soon as 4 d after amyloid induction, whereas the number of MMZM remains unaffected. Depletion of spleen macrophages with clodronate before amyloid induction delays amyloid deposition (Lundmark et al. 2013; Kennel et al. 2014). However, the spleen is not absolutely necessary for the development of AA amyloidosis because the disease can also be initiated in splenectomized animals, although more slowly (Kisilevsky and Benson 1981).

Cross-Seeding in the Animal AA Model

A number of studies have shown that AA amyloidosis in mice can be accelerated by fibrils from the same species and by fibrils extracted from other mammals (for review, see Westermark and Westermark 2010; Westermark et al. 2015). Also, human AL fibrils can have the same effect (Liu et al. 2007; P Westermark, O Suhr, B-G Ericzon, et al., unpubl.). In addition, nonamyloid fibrils like silk, bacterial curli (Lundmark et al. 2005), synthetic fibrils of peptides corresponding to non-AA amyloid segments (Lundmark et al. 2002), and peptide fibrils designed for tissue repair (Westermark et al. 2009) can have an amyloid-accelerating effect.

Seeding or Cross-Seeding Human AA Amyloid

Studies of seeding and cross-seeding in peripheral (non–central nervous system [CNS]) amyloid forms in humans are difficult and result in little definite data. However, AA amyloidosis is transmissible in many mammalian and avian species. It is therefore likely that it is a disease that can also be transmitted in humans if the conditions are right (i.e., a persistently high plasma concentration of SAA and exposure to a seeding structure). It is likely that transmission among humans is rare and cross-seeding is more common.

AA amyloidosis is common in many mammalian and avian species, including some commonly used in the human food chain, particularly domesticated waterfowls such as Pekin duck and goose (Anser anser domesticus). Development of AA amyloidosis is a common problem and a cause of economic loss for goose breeders (Kovács et al. 2005). Amyloid is deposited in the liver, and unsurprisingly, amyloid can be found in bird livers sold as human food as well as in processed food such as foie gras (Solomon et al. 2007). AA amyloidosis is also present in cattle (Bos taurus), and amyloid has been demonstrated in the organs of apparently healthy animals after slaughter in Japan (Tojo et al. 2005; Yoshida et al. 2009) and the Netherlands (Gruys 1977).

There are no reports on transmission of any peripheral amyloid form, including AA, among humans. Furthermore, there is no evidence that any kind of amyloidosis develops as a result of ingesting amyloid-containing food. In a country like France, where foie gras is commonly eaten, a higher incidence of AA amyloidosis may be expected. However, AA amyloidosis is comparably rare in the Western world, and effects of a potential risk factor like amyloid-containing food would be difficult to identify.

Transthyretin-Derived Amyloidosis

Transthyretin (TTR) is a plasma transport protein for thyroxin and indirectly for retinol. Most circulating TTR is produced by hepatocytes, but TTR is also expressed in retina, choroid plexus epithelial cells, and glucagon cells in pancreatic islets.

Circulating TTR is a homotetramer in which each of the 127-amino-acid residue monomers contains two β-sheets, each consisting of four strands. The monomer also has a short α-helix. The tetramer is likely not amyloidogenic, and an important step in fibrillogenesis is dissociation of the tetramer into monomers (Kelly and Lansbury 1994; Johnson et al. 2012).

TTR is the fibril protein in most forms of hereditary amyloidoses. The cause is a mutation in the TTR gene, usually leading to amino acid substitution at a single position. More than 100 amyloid-generating mutations are known and span almost the whole mature TTR molecule (Rowczenio et al. 2014). These mutations slightly decrease the stability of the quaternary and tertiary structure of TTR (Hurshman Babbes et al. 2008) and thereby increase the availability of amyloidogenic monomers. Consistent with this conclusion is the finding that the most destabilizing mutation (TTR L55P) is associated with the most aggressive form of hereditary ATTR amyloidosis (Hurshman Babbes et al. 2008).

The hereditary ATTR amyloidoses have highly varying phenotypes. Cardiomyopathy and polyneuropathy, alone or in varying combinations, are predominate, but other manifestations, including symptoms of the eyes, kidneys, and CNS, may occur. Interestingly, liver manifestations are rarely seen despite the liver’s role in circulating TTR. Different mutations are generally associated with specific phenotypes, but within the same mutation, there is sometimes a high variability. The most common mutation associated with polyneuropathy is TTRV30M (the disease is most often referred to as familial amyloidosis polyneuropathy [FAP]). Also, ATTRV30M amyloidosis varies in phenotype, and although some patients mainly suffer from polyneuropathy, others develop a severe and eventually lethal cardiomyopathy (Suhr et al. 2003; Rapezzi et al. 2012, 2013).

Additionally, WT TTR is an amyloidogenic protein and the main component in the prevalent senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA), which may affect as many as 20%–25% of individuals more than 80 years of age (Westermark et al. 1979; Cornwell et al. 1983; Tanskanen et al. 2006). In most persons, the deposits are small and probably without clinical significance, but, in some cases, WT-ATTR amyloidosis is associated with severe cardiomyopathy attributable to massive heart infiltration. Other manifestations, including carpal tunnel syndrome (Gioeva et al. 2013) and lumbar spinal stenosis (Westermark et al. 2014), may occur, although the prevalence is insufficiently known. It is notable that SSA is cardiomyopathic and usually not associated with overt polyneuropathy.

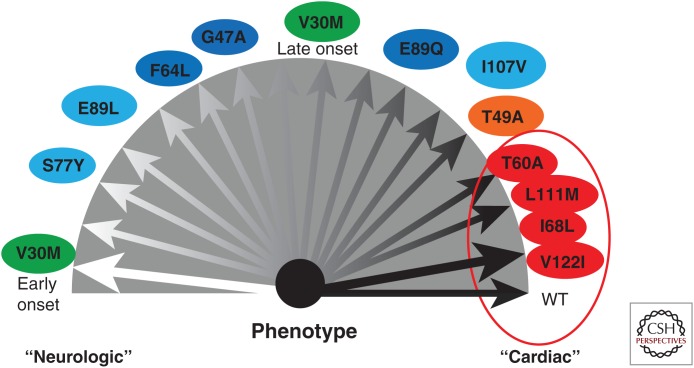

Thus, although SSA has a rather homogenous phenotype, there is a high degree of variability in the hereditary TTR amyloidoses (Fig. 2) (Rapezzi et al. 2013). The causes of the variability between and within the different TTR diseases are not understood. Interestingly, ATTRV30M amyloidosis appears in two different molecular variants, one in which the amyloid consists of full-length molecules only and the other in which fibrils contain a mixture of full-length and C-terminal fragments of TTR (Westermark et al. 1987a; Bergström et al. 2005; Ihse et al. 2008). It is often possible to discriminate between these two types of amyloid. Amyloid consisting of full-length TTR molecules has a stronger affinity for Congo red and exhibits a much stronger birefringence compared with fragment-containing material (Bergström et al. 2005; Ihse et al. 2008). Differences are also seen using electron microscopy, as full-length TTR fibrils are longer, arranged in parallel, and are differently deposited at cardiomyocytes (Bergström et al. 2005). TTR cleavage is likely not a secondary event after fibril formation but of central importance in fibrillogenesis (Bateman et al. 2011; Mangione et al. 2014).

Figure 2.

Schematic of the phenotypes associated with different transthyretin (TTR) mutations, some of which are polyneuropathic and other cardiomyopathic. Note that ATTR V30M amyloidosis appears in two phenotypic forms, which are associated with differences in fibril protein composition. (From Rapezzi et al. 2013; reprinted, with permission, from Oxford University Press © 2013.)

There is an association between the two molecular forms and different clinical phenotypes in ATTRV30M amyloidosis. Those with only full-length TTR in their deposits tend to develop the disease at a younger age, have more severe polyneuropathy, and usually do not develop restrictive cardiomyopathy (Ihse et al. 2008). They may have, however, deposits in the myocardium, including some amyloid fibrils within cardiomyocytes (Bergström et al. 2005). Subjects with TTR fragments in amyloid fibrils are diagnosed at an older age and have less polyneuropathic problems but have a progressive cardiomyopathy with a distinctive distribution of amyloid, which differs from that in subjects with full-length ATTR amyloid (Bergström et al. 2005). Amyloid in heterozygous subjects contains a mixture of mutant and WT-ATTR. Fibrils with TTR fragments contain significantly more WT TTR compared with fibrils only containing full-length molecules (Ihse et al. 2011).

Since 1991, liver transplantation has been a major treatment of hereditary ATTR amyloidosis, particularly in patients with the V30M (p.V50M) mutation (Holmgren et al. 1991). This is a kind of gene therapy by which the liver producing a mutant TTR is replaced by one expressing only WT protein and often halts the progression of the disease. However, amyloid containing fragmented TTR recruits WT TTR, and, therefore, amyloid cardiomyopathy tends to progress after liver transplantation in these individuals (Gustafsson et al. 2012). Most non-TTRV30M amyloid forms have fibrils with TTR fragments and cardiomyopathy that progress after liver transplantation (Ihse et al. 2013).

Transmission of ATTR Amyloidosis

Because there is a shortage of donors, so-called domino transplantation occurs in patients in critical need of a liver transplant. In these cases, the transplanted liver is well functioning but contains a small amount of amyloid. More than 1000 domino transplantations have been performed worldwide since 2013 (www.fapwtr.org/ram1.htm) with excellent primary results. Because hereditary ATTR amyloidosis almost never develops before adulthood and is mostly found in older patients, problems with amyloidosis were not expected to occur in transplant recipients (Ericzon et al. 2008). However, a number of patients developed progressive ATTR amyloidosis with typical neuropathic symptoms within 6–9 years after transplantation (Lladó et al. 2010; Abdelfatah et al. 2014). There are several possible explanations for this rapid development of amyloidosis. There are small amyloid deposits in the vessel walls of the transplant, which may act as seeds in the recipient. In younger TTR mutation carriers, the liver chaperone system can hinder misfolded TTR to escape from the cells, but the protection system deteriorates with age (Balch et al. 2008; Powers et al. 2009). Therefore, another equally possible mechanism for the unexpected rapid development of amyloidosis in recipients may be a defective hepatocyte control function. This issue is comparable with late-onset, prion-associated neurodegenerative disorders (Prusiner 2013).

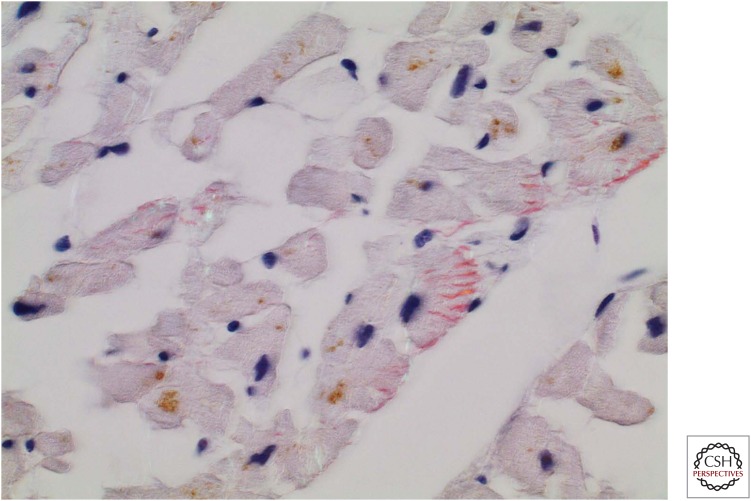

Details concerning patients with amyloidosis resulting from domino transplantation are scarce. In the cases we have studied, only full-length ATTR molecules have been identified (P Westermark, unpubl.). Amyloidosis in the heart is identical with that described for ordinary full-length ATTR amyloidosis, including the presence of intracellular amyloid (Fig. 3). Because most patients who undergo liver transplantation for hereditary ATTRV30M amyloidosis are <50 years of age, the donor amyloid is most likely of full-length type. Thus, present knowledge may support the hypothesis that the two identified types of ATTR fibrils are examples of strains (Westermark and Westermark 2010), indicating that the amyloid “strain” is determined by the transplanted liver and not by factors in the recipient.

Figure 3.

Section of myocardium from a recipient of a domino transplant liver who developed ATTR amyloidosis 8 years after transplant. Amyloid deposits are fairly scarce but can be seen outside cardiomyocytes and intracellularly. Tissue stained with Congo red with partially crossed polarizers.

Islet Amyloid Polypeptide and Type 2 Diabetes

Islet amyloid was described more than 100 years ago, and it was a surprise when 85 years later it turned out to contain a previously unknown β-cell polypeptide hormone, now named islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) or amylin (Westermark et al. 1986, 1987, 2011; Cooper et al. 1988). IAPP is a 37-residue-long polypeptide that is produced by cleavage of proIAPP, which consists of 67 residues in humans. ProIAPP processing occurs at dibasic residues by the prohormone convertases PC2 and PC1/3 and results in the removal of an N- and C-terminal flanking peptide, respectively (Marzban et al. 2005). Further posttranslational modifications are needed to gain biological activity and comprise formation of a disulfate bridge between residues 2 and 7 and a C-terminal amidation. IAPP is a member of the calcitonin family and signals via the calcitonin receptor (CR) when combined with receptor activity modifying protein 1 or 3 (RAMP1 or 3) (for a review, see Westermark and Westermark 2013). CR and RAMP1/3 mRNA are detected in several tissues, but because our knowledge on IAPP signaling effects is limited, conclusions tend to be speculative. In humans, IAPP is mainly produced by islet β-cells and is present in circulation at picomolar levels. The main lesson from IAPP knockout mice is that glucose challenge increases insulin release, and mice clear glucose significantly more efficiently compared to WT animals (Gebre-Medhin et al. 1998). This mechanism is comparable to that observed from islets incubated with IAPP antagonist IAPP8-37, which impedes the IAPP inhibitory effect on insulin secretion (Wang et al. 1993). Results support autocrine and/or paracrine function for IAPP but do not exclude its peripheral effects (Lutz 2012).

IAPP in human, monkey, and cat is a highly amyloidogenic peptide, whereas IAPP in most rodents is not. This difference depends on divergences in the amino acid sequence, mainly in the 20-29 segment (Betsholtz et al. 1989). An unsolved question until now is how human IAPP (hIAPP) avoids aggregation in vivo despite a high local concentration in secretory granules. Other granule components, including insulin, proinsulin, C-peptide, and metal ions, may affect amyloidogenesis (Chargé et al. 1995; Westermark et al. 1996).

Type 2 diabetes results from disturbances in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis and is preceded by a long compensatory state with β-cell stress and overproduction of insulin (Kahn 2003). Under normal conditions, proinsulin constitutes <10% of insulin-reactive material released from β-cells, but during the development of type 2 diabetes, there is a period of increased hormone release concomitant with an increase of the proinsulin fraction (Roder et al. 1998). Because proinsulin and proIAPP undergo posttranslational processing carried out by the same convertases, a similar increase in proIAPP is expected. ProIAPP expression in endocrine cells (GH4C1) without PC1/3 and PC2 increases the risk for intracellular amyloid formation (Paulsson and Westermark 2005). Immunological analysis of intracellular fibrils present in the halo region of the secretory granules has revealed proIAPP as a fibril component. Therefore, both increased expression and incomplete processing of proIAPP are likely important in islet amyloidogenesis.

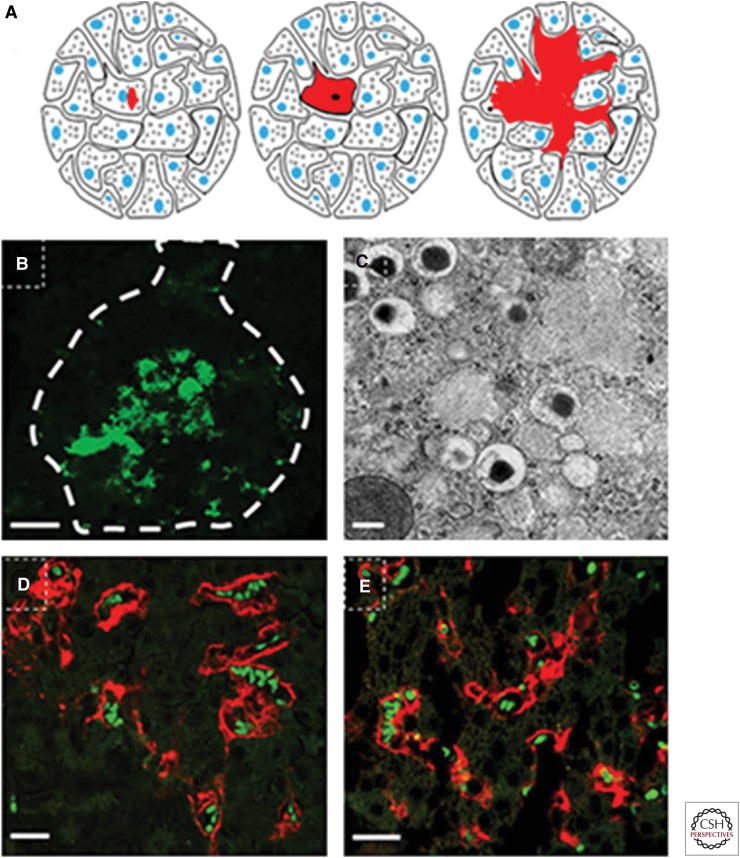

Seeding IAPP Amyloid In Vivo

Deposition of amyloid starts in a few islets, but as the amount of deposited amyloid grows, the number of affected islets increases (Westermark 1972; Hull et al. 2004). One question, therefore, is whether islet amyloid can spread by seeding or whether each islet is isolated. We have produced fibrils from recombinant hIAPP and hproIAPP exhibiting amyloid characteristics such as affinity for Congo red and fibrillar structure when viewed with transmission electron microscopy. These fibrils were used to study IAPP seeding in vivo and were injected into the tail vein of mice expressing hIAPP under the insulin 1 promotor, whereas control mice received non-IAPP fibrils (Oskarsson et al. 2015). Both hIAPP and hproIAPP fibril injections lead to an increased prevalence and degree of islet amyloidosis (Oskarsson et al. 2015). Interestingly, amyloid distribution patterns differed between mice with seeded IAPP depositions and those with spontaneous amyloid. Seeded amyloid was apparent along islet vessels that appeared dilated, whereas amyloid deposits in nonseeded mice were restricted to small intracellular deposits (Oskarsson et al. 2015). The perivascular pattern should be expected for seeding of IAPP released from cells (Fig. 4) and is often seen in human pancreatic specimens (Westermark 1973). These results also show that a localized peripheral amyloid can be induced by hematogenous seeding with synthetic fibrils.

Figure 4.

Cartoon depicting islet amyloid development. (A) (Left to right) Islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) aggregation starts intracellularly in membrane-enclosed compartments (e.g., secretory granules or endoplasmic reticulum [ER]). When the amyloid mass expands, it replaces the cytoplasm and results in cell death. Any amyloid that avoids degradation will now serve as a seed for sustained amyloid formation. IAPP released from surrounding β-cells constitutes the new amyloid. As the extracellular amyloid mass increases, islet cells become compressed, and finger-like bundles of amyloid penetrate between β-cells and destroy cell–cell interaction, and fibrillation activates the death receptor that results in caspase 3 activation. (B) Human islet with amyloid developed during culture at high glucose for 14 days. Amyloid with a spotty appearance is seen throughout the islet. Amyloid labeled with thioflavin T is viewed at excitation 488 nm with an argon laser. The islet surface is highlighted with a dashed line. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) Part of a β-cell with intracellular amyloid from human IAPP (hIAPP) transgenic mouse viewed in a transmission electron microscope. Amyloid fibrils are found in secretory granules. Scale bar, 200 nm. (D,E) Islets with extracellular amyloid (red) from mouse injected with preformed fibrils from hIAPP (D) and amyloid-β (Aβ) (E). Scale bars, 50 µm. Amyloid is stained with Congo red displaying a fluorescence emission spectra at 546 nm. Erythrocytes appear green because of autofluorescence.

Cross-Seeding IAPP Amyloid In Vivo

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of IAPP and amyloid-β (Aβ) showed significant similarity between the local amyloid peptides (Westermark 1994). In vitro studies showed that the peptides can interact and that Aβ fibrils efficiently seed IAPP fibril formation (O’Nuallian et al. 2004). Aβ fibrils were generated from synthetic peptides and injected into the tail vein of hIAPP transgenic mice. Aβ fibrils were found to seed IAPP in vivo as efficiently as hproIAPP (Oskarsson et al. 2015). This finding is of particular interest because epidemiological studies point to an almost twofold increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease among patients with type 2 diabetes (Leibson et al. 1997; Ott et al. 1999) and offers a possible molecular link between the two prevalent amyloid-related diseases. Finding IAPP in human cerebral Aβ deposits was also of interest (Oskarsson et al. 2015).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Proven or possible transmission of systemic amyloidosis in animals by seeding mechanisms has been shown in the AA and AApoAII forms. Furthermore, it has been shown that amyloid localized to the islets of Langerhans can be induced by hematogenous seeding with preformed IAPP fibrils. Also, cross-seeding can be efficient in amyloidogenesis and may be a link between different protein-misfolding diseases. Although the only known example of transmission of a noncerebral amyloidosis in humans is ATTR amyloidosis, we suspect that cross-seeding may be a common mechanism for development of different forms of amyloidosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research is supported by the Swedish Research Council, FAMY, FAMY Norrbotten and Amyl Foundation, County Council of Östergötland, Selander's Foundation, and the Swedish Diabetes Association. M.F. is additionally supported by the German Research Council (FA 456/15-1).

Footnotes

Editor: Stanley B. Prusiner

Additional Perspectives on Prion Diseases available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Abdelfatah MM, Hayman SR, Gertz MA. 2014. Domino liver transplantation as a cause of acquired familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Amyloid 21: 136–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrad MA, Kisilevsky R, Willmer J, Chen SJ, Skinner M. 1982. Further characterization of amyloid-enhancing factor. Lab Invest 47: 139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. 2008. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science 319: 916–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman DA, Tycko R, Wickner RB. 2011. Experimentally derived structural constraints for amyloid fibrils of wild-type transthyretin. Biophys J 101: 2485–2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benditt EP. 1976. The structure of amyloid protein AA and evidence for a transmissible factor in the origin of amyloidosis. In Amyloidosis (ed. Wegelius O, Pasternack A). Academic, London. [Google Scholar]

- Bergström J, Gustavsson Å, Hellman U, Sletten K, Murphy CL, Weiss DT, Solomon A, Olofsson BO, Westermark P. 2005. Amyloid deposits in transthyretin-derived amyloidosis: Cleaved transthyretin is associated with distinct amyloid morphology. J Path 206: 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsholtz C, Svensson V, Rorsman F, Engström U, Westermark GT, Wilander E, Johnson KH, Westermark P. 1989. Islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP): cDNA cloning and identification of an amyloidogenic region associated with species-specific occurrence of age-related diabetes mellitus. Exp Cell Res 183: 484–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodin K, Ellmerich S, Kahan MC, Tennent GA, Loesch A, Gilbertson JA, Hutchinson WL, Mangione PP, Gallimore JR, Millar DJ, et al. 2010. Antibodies to human serum amyloid P component eliminate visceral amyloid deposits. Nature 468: 93–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathcart ES, Comerford FR, Cohen AS. 1965. Immunologic studies on a protein extracted from human secondary amyloid. N Engl J Med 273: 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chargé SB, de Koning EJ, Clark A. 1995. Effects of pH and insulin on fibrillogenesis of islet amyloid polypeptide in vitro. Biochemistry 34: 14588–14593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon W, Lai Z, McCutchen SL, Miroy GJ, Strang C, Kelly JW. 1996. FAP mutations destabilize transthyretin facilitating conformational changes required for amyloid formation. In The nature and origin of amyloid fibrils (ed. Bock GR, Goode JA). Wiley, Chichester, UK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GJ, Leighton B, Dimitriadis GD, Parry-Billings M, Kowalchuk JM, Howland K, Rothbard JB, Willis AC, Reid KB. 1988. Amylin found in amyloid deposits in human type 2 diabetes mellitus may be a hormone that regulates glycogen metabolism in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci 85: 7763–7767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell GG III, Murdoch WL, Kyle RA, Westermark P, Pitkänen P. 1983. Frequency and distribution of senile cardiovascular amyloid. Am J Med 75: 618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. 1990. Sickle cell hemoglobin polymerization. Adv Protein Chem 40: 63–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Jucker M. 2012. The amyloid state of protein in human diseases. Cell 148: 1188–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elimova E, Kisilevsky R, Ancsin JB. 2009. Heparan sulfate promotes the aggregation of HDL-associated serum amyloid A: Evidence for a proamyloidogenic histidine molecular switch. FASEB J 23: 3436–3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericzon BG, Larsson M, Wilczek HE. 2008. Domino liver transplantation: Risks and benefits. Transplant Proc 40: 1130–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney PM, Imai DM, Clifford DL, Ghassemian M, Sasik R, Chang AN, O’Brien TD, Coppinger J, Trejo M, Masliah E, et al. 2014. Proteomic analysis of highly prevalent amyloid A amyloidosis endemic to endangered island foxes. PLoS ONE 9: e113765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganowiak K, Hultman P, Engström U, Gustavsson Å, Westermark P. 1994. Fibrils from synthetic amyloid-related peptides enhance development of experimental AA-amyloidosis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 199: 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre-Medhin S, Mulder H, Pekny M, Zhang YZ, Törnell J, Westermark P, Westermark GT, Sundler F, Ahrén B, Betsholtz C. 1998. Increased insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in mice lacking islet amyloid polypeptide (amylin). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 250: 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioeva Z, Urban P, Meliss RR, Haag J, Axmann HD, Siebert F, Becker K, Radtke HG, Röcken C. 2013. ATTR amyloid in the carpal tunnel ligament is frequently of wildtype transthyretin origin. Amyloid 20: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruys E. 1977. Amyloidosis in the bovine kidney. Vet Sci Commun 1: 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson S, Ihse E, Henein MY, Westermark P, Lindqvist P, Suhr OB. 2012. Amyloid fibril composition as a predictor of development of cardiomyopathy after liver transplantation for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Transplantation 93: 1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt F. 1971. Transfer amyloidosis. I: Studies on the transfer of various lymphoid cells from amyloidotic mice to syngeneic nonamyloidotic recipients. II: Induction of amyloidosis in mice with spleen, thymus and lymphnode tissue from casein-sensitized syngeneic donors. Am J Path 65: 411–424. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt F, Ranløv PJ. 1976. Transfer amyloidosis. Int Rev Exp Pathol 16: 273–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JD, Lansbury PT. 1997. Models of amyloid seeding in Alzheimer’s disease and scrapie: Mechanistic truths and physiological consequences of the time-dependent solubility of amyloid proteins. Ann Rev Biochem 66: 385–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hol PR, Snel FW, Niewold TA, Gruys E. 1986. Amyloid-enhancing factor (AEF) in the pathogenesis of AA-amyloidosis in the hamster. Virchows Arch B 52: 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren G, Steen L, Ekstedt J, Groth CG, Ericzon BG, Eriksson S, Andersen O, Karlberg I, Nordén N, Nakazato M, et al. 1991. Biochemical effect of liver transplantation in two Swedish patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP-met30). Clin Genet 40: 242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull RL, Westermark GT, Westermark P, Kahn SE. 2004. Islet amyloid: A critical entity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 3629–3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurshman Babbes AR, Powers ET, Kelly JW. 2008. Quantification of the thermodynamically linked quaternary and tertiary structural stabilities of transthyretin and its disease-associated variants: The relationship between stability and amyloidosis. Biochemistry 47: 6969–6984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihse E, Ybo A, Suhr OB, Lindqvist P, Backman C, Westermark P. 2008. Amyloid fibril composition is related to the phenotype of hereditary transthyretin V30M amyloidosis. J Path 216: 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihse E, Suhr OB, Hellman U, Westermark P. 2011. Variation in amount of wild-type transthyretin in different fibril and tissue types in ATTR amyloidosis. J Mol Med 89: 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihse E, Rapezzi C, Merlini G, Ando Y, Suhr OB, Ikeda S, Lavatelli F, Obici L, Quarta CC, Leone O, et al. 2013. Amyloid fibrils containing fragmented ATTR may be the standard fibril composition in ATTR amyloidosis. Amyloid 20: 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii W, Liepnieks JJ, Yamada T, Benson MD, Kluve-Beckerman B. 2013. Human SAA1-derived amyloid deposition in cell culture: A consistent model utilizing human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and serum-free medium. Amyloid 20: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett JT, Lansbury PT. 1993. Seeding “one-dimensional crystallization” of amyloid: A pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease and scrapie? Cell 73: 1055–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johan K, Westermark GT, Engström U, Gustavsson Å, Hultman P, Westermark P. 1998. Acceleration of AA-amyloidosis by amyloid-like synthetic fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 2558–2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Connelly S, Fearns C, Powers ET, Kelly JW. 2012. The transthyretin amyloidoses: From delineating the molecular mechanism of aggregation linked to pathology to a regulatory-agency-approved drug. J Mol Biol 421: 185–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn SE. 2003. The relative contributions of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction to the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 46: 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JW, Lansbury PT. 1994. A chemical approach to elucidate the mechanism of transthyretin and β-protein amyloid fibril formation. Amyloid 1: 186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kennel SJ, Macy S, Wooliver C, Huang Y, Richey T, Heidel E, Wall JS. 2014. Phagocyte depletion inhibits AA amyloid accumulation in AEF-induced huIL-6 transgenic mice. Amyloid 21: 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisilevsky R, Benson MD. 1981. Serum amyloid A induction does not require the spleen. Lab Invest 44: 84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisilevsky R, Manley PN. 2012. Acute phase serum amyloid A: Perspectives on its physiological and pathological roles. Amyloid 19: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles TP, Waudby CA, Devlin GL, Cohen SI, Aguzzi A, Vendruscolo M, Terentjev EM, Welland ME, Dobson CM. 2009. An analytical solution to the kinetics of breakable filament assembly. Science 326: 1533–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenaga T, Fu X, Xing Y, Matsusita T, Kuramoto K, Syumiya S, Hasegawa K, Niaiki H, Ueno M, Ishihara T, et al. 2004. Tissue distribution, biochemical properties, and transmission of mouse type A AApoAII amyloid fibrils. Am J Path 164: 1597–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács BM, Szilágyi L, Janan J, Rudas P. 2005. Serum amyloid A in geese; cloning and expression of recombinant protein. Amyloid 12: 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibson CL, Rocca WA, Hanson VA, Cha R, Kokmen E, O’Brien PC, Palumbo PJ. 1997. Risk of dementia among persons with diabetes mellitus: A population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 145: 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JP, Galvis ML, Gong F, Zhang X, Zcharia E, Metzger S, Vlodavsky I, Kisilevsky R, Lindahl U. 2005. In vivo fragmentation of heparan sulfate by heparanase overexpression renders mice resitant to amyloid protein A amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 6473–6477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl U, Kjellén L. 2013. Pathophysiology of heparan sulphate: Many diseases, few drugs. J Intern Med 273: 555–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Cui D, Hoshii Y, Kawano H, Une Y, Gondo T, Ishihara T. 2007. Induction of murine AA amyloidosis by various homogeneous amyloid fibrils and amyloid-like synthetic peptides. Scand J Immunol 66: 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lladó L, Baliellas C, Casasnovas C, Ferrer I, Fabregat J, Ramos E, Castellote J, Torras J, Xiol X, Rafecas A. 2010. Risk of transmission of systemic transthyretin amyloidosis after domino liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 16: 1386–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Yu Y, Zhu I, Cheng Y, Sun PD. 2014. Structural mechanism of serum amyloid A-mediated inflammatory amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: 5189–5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark K, Westermark GT, Nyström S, Murphy CL, Solomon A, Westermark P. 2002. Transmissibility of systemic amyloidosis by a prion-like mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 6979–6984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark K, Westermark GT, Olsén A, Westermark P. 2005. Protein fibrils in nature can enhance AA amyloidosis in mice: Cross-seeding as a disease mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 6098–6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark K, Vahdat Shariatpanahi A, Westermark GT. 2013. Depletion of spleen macrophages delays AA amyloid development: A study performed in the rapid mouse model of AA amyloidosis. PLoS ONE 8: e79104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz TA. 2012. Control of energy homeostasis by amylin. Cell Mol Life Sci 69: 1947–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magy N, Benson MD, Liepnieks JJ, Kluve-Beckerman B. 2007. Cellular events associated with the initial phase of AA amyloidogenesis: Insights from a human monocyte model. Amyloid 14: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maji SK, Perrin MH, Sawaya MR, Jessberger S, Vadodaria K, Rissman RA, Singru PS, Nilsson KP, Simon R, Schubert D, et al. 2009. Functional amyloids as natural storage of peptide hormones in pituitary secretory granules. Science 325: 328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione PP, Porcari R, Gillmore JD, Pucci P, Monti M, Porcari M, Giorgetti S, Marchese L, Raimondi S, Serpell LC, et al. 2014. Proteolytic cleavage of Ser52Pro variant transthyretin triggers its amyloid fibrillogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: 1539–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzban L, Trigo-Gonzalez G, Verchere CB. 2005. Processing of pro-islet amyloid polypeptide in the constitutive and regulated secretory pathways of β cells. Mol Endocrinol 19: 2154–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdam KP, Raynes JG, Alpers MP, Westermark GT, Westermark P. 1996. Amyloidosis: A global problem common in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Med J 39: 284–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen SL, Colon W, Kelly JW. 1993. Transthyretin mutation Leu-55-Pro significantly alters tetramer stability and increases amyloidogenicity. Biochemistry 16: 12119–12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlini G, Bellotti V. 2003. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 349: 583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlini G, Westermark P. 2004. The systemic amyloidosis: Clearer understanding of the molecular mechanisms offer hope for more effective therapies. J Intern Med 255: 159–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlini G, Comenzo RL, Seldin DC, Wechalekar A, Gertz MA. 2014. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis. Expert Rev Hematol 7: 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mukherjee A, Soto C. 2017. Prion-like protein aggregates and type 2 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a024315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Naeem M, Inoshima Y, Yanai T, Goryo M, Ishiguro N. 2017. Experimental induction and oral transmission of avian AA amyloidosis in vaccinated white hens. Amyloid 20: 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewold TA, Hol PR, van Andel AC, Lutz ET, Gruys E. 1987. Enhancement of amyloid induction by amyloid fibril fragments in hamster. Lab Invest 56: 544–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noborn F, Ancsin JB, Ubhayasekera W, Kisilevsky R, Li JP. 2012. Heparan sulfate dissociates serum amyloid A (SAA) from acute-phase high-density lipoprotein, promoting SAA aggregation. J Biol Chem 287: 25669–25677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nuallian B, Williams AD, Westermark P, Wetzel R. 2004. Seeding specificity in amyloid growth induced by heterologous fibrils. J Biol Chem 279: 17490–17499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosawa F, Asakura S. 1975. Thermodynamics of the polymerization of protein. Academic, London. [Google Scholar]

- Oskarsson ME, Paulsson JF, Schultz SW, Ingelsson M, Westermark P, Westermark GT. 2015. In vivo seeding and cross-seeding of localized amyloidosis: A molecular link between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Path 185: 834–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott A, Stolk RP, van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. 1999. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam study. Neurology 53: 1937–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsson JF, Westermark GT. 2005. Aberrant processing of human proislet amyloid polypeptide results in increased amyloid production. Diabetes 54: 2117–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinney JH, Hawkins PN. 2012. Amyloidosis. Ann Clin Biochem 49: 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers ET, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW, Balch WE. 2009. Biological and chemical approaches to diseases of proteostasis deficiency. Annu Rev Biochem 2009: 959–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. 2013. Biology and genetics of prions causing neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Genet 47: 601–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchtler H, Sweat F, Levine M. 1962. On the binding of Congo red by amyloid. J Histochem Cytochem 10: 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Quintas A, Saraiva MJ, Brito RM. 1999. The tetrameric protein transthyretin dissociates to a non-native monomer in solution. A novel model for amyloidogenesis. J Biol Chem 274: 32943–32949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapezzi C, Longhi S, Milandri A, Lorenzini M, Gagliardi C, Gallelli I, Leone O, Quarta CC. 2012. Cardiac involvement in hereditary-transthyretin related amyloidosis. Amyloid 19: 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapezzi C, Quarta C, Obici L, Perfetto F, Longhi S, Salvi F, Biagini E, Lorenzini M, Grigioni F, Leone O, et al. 2013. Disease profile and differential diagnosis of hereditary transthyretin-related amyloidosis with exclusively cardiac phenotype: An Italian perspective. Eur Heart J 34: 520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roder ME, Porte DJ, Schwartz RS, Kahn SE. 1998. Disproportionately elevated proinsulin levels reflect the degree of impaired B cell secretory capacity in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowczenio DM, Noor I, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, Whelan CJ, Hawkins PN, Obici L, Westermark P, Grateau G, Wechalekar AD. 2014. Online registry for mutations in hereditary amyloidosis including nomenclature recommendations. Hum Mutat 35: E2403–E2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safar JG, Lessard P, Tamgüney G, Freyman Y, Deering C, Letessier F, Dearmond SJ, Prusiner SB. 2008. Transmission and detection of prions in feces. J Infect Dis 198: 81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya MR, Sambashivan S, Nelson R, Ivanova MI, Sievers SA, Apostol MI, Thompson MJ, Balbirnie M, Wiltzius JJ, McFarlane HT, et al. 2007. Atomic structures of amyloid cross-β spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature 447: 453–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipe JD, Benson MD, Ikeda S, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Westermark P. 2014. Updated nomenclature 2014: Amyloid fibril proteins and clinical classification of the amyloidoses. Amyloid 21: 221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow AD, Bramson R, Mar H, Wight TN, Kisilevsky R. 1991. A temporal and ultrastructural relationship between heparan sulfate proteoglycans and AA amyloid in experimental amyloidosis. J Histochem Cytochem 39: 1321–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon A, Richey T, Murphy CL, Weiss DT, Wall JS, Westermark GT, Westermark P. 2007. Amyloidogenic potential of foie gras. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 10998–11001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørby R, Espenes A, Landsverk T, Westermark G. 2008. Rapid induction of experimental AA amyloidosis in mink by intravenous injection of amyloid enhancing factor. Amyloid 15: 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponarova J, Nyström S, Westermark GT. 2008. AA-amyloidosis can be transferred by peripheral blood monocytes. PLoS ONE 3: e3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhr OB, Svendsen IH, Andersson R, Danielsson A, Holmgren G, Ranlöv PJ. 2003. Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis from a Scandinavian perspective. J Intern Med 254: 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanskanen M, Kiuru-Enari S, Tienari P, Polvikoski T, Verkkoniemi A, Rastas S, Sulkava R, Paetau A. 2006. Senile systemic amyloidosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and dementia in a very old Finnish population. Amyloid 13: 164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tojo K, Tokuda T, Hoshii Y, Fu X, Higuchi K, Matsui T, Kametani F, Ikeda SI. 2005. Unexpectedly high incidence of visceral AA-amyloidosis in slaughtered cattle in Japan. Amyloid 12: 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama BH, Weissman JS. 2011. Amyloid structure: Conformational diversity and consequences. Annu Rev Biochem 80: 557–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZL, Bennet WM, Ghatei MA, Byfield PG, Smith DM, Bloom SR. 1993. Influence of islet amyloid polypeptide and the 8–37 fragment of islet amyloid polypeptide on insulin release from perifused rat islets. Diabetes 42: 330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werdelin O, Ranløv P. 1966. Amyloidosis in mice produced by transplantation of spleen cells from casein-treated mice. Acta Path Microbiol Scand 68: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P. 1972. Quantitative studies of amyloid in the islets of Langerhans. Upsala J Med Sci 77: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P. 1973. Fine structure of islets of Langerhans in insular amyloidosis. Virchows Arch A 359: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P. 1994. Amyloid and polypeptide hormones: What is their inter-relationship? Amyloid 1: 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P. 2012. Subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsy for amyloid protein studies. Methods Mol Biol 849: 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Nilsson GT. 1984. Demonstration of amyloid protein A in old museum specimens. Arch Path Lab Med 108: 217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark GT, Westermark P. 2010. Prion-like aggregates: Infectious agents in human disease. Trends Mol Med 16: 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark GT, Westermark P. 2013. Islet amyloid polypeptide and diabetes. Curr Protein Pept Sci 14: 330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Johansson B, Natvig JB. 1979. Senile cardiac amyloidosis: Evidence of two different amyloid substances in the ageing heart. Scand J Immunol 10: 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Wernstedt C, Wilander E, Sletten K. 1986. A novel peptide in the calcitonin gene related peptide family as an amyloid fibril protein in the endocrine pancreas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 140: 827–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Sletten K, Olofsson BO. 1987a. Prealbumin variants in the amyloid fibrils of Swedish familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Clin Exp Immunol 69: 695–701. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Wernstedt C, Wilander E, Hayden DW, O’Brien TD, Johnson KH. 1987b. Amyloid fibrils in human insulinoma and islets of Langerhans of the diabetic cat are derived from a neuropeptide-like protein also present in normal islet cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84: 3881–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Li ZC, Westermark GT, Leckström A, Steiner DF. 1996. Effects of β cell granule components on human islet amyloid polypeptide fibril formation. FEBS Lett 379: 203–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Lundmark K, Westermark GT. 2009. Fibrils from designed non-amyloid-related synthetic peptides induce AA-amyloidosis during inflammation in an animal model. PLoS ONE 4: e6041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Andersson A, Westermark GT. 2011. Islet amyloid polypeptide, islet amyloid and diabetes mellitus. Physiol Rev 91: 795–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Westermark GT, Suhr OB, Berg S. 2014. Transthyretin-derived amyloidosis: Probably a common cause of lumbar spinal stenosis. Ups J Med Sci 119: 223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark GT, Fändrich M, Westermark P. 2015. AA amyloidosis: Pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 10: 321–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wille H, Baldwin MA, Cohen FE, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. 1996. Prion protein amyloid: Separation of scrapie infectivity from PrP polymers. In The nature and origin of amyloid fibrils (ed. Bock GR, Goode JA). Wiley, Chichester, UK. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y, Nakamura A, Chiba T, Kogishi K, Matsushita T, Li F, Guo Z, Hosokawa M, Mori M, Higuchi K. 2001. Transmission of mouse senile amyloidosis. Lab Invest 81: 493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue WF, Homans SW, Radford SE. 2008. Systematic analysis of nucleation-dependent polymerization reveals new insights into the mechanism of amyloid self-assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 8926–8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Zhang P, Fu X, Higuchi K, Ikeda SI. 2009. Slaughtered aged cattle might be one dietary source exhibiting amyloid enhancing factor activity. Amyloid 16: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Une Y, Fu X, Yan J, Ge F, Yao J, Sawashita J, Mori M, Tomozawa H, Kametani F, et al. 2008. Fecal transmission of AA amyloidosis in the cheetah contributes to high incidence of disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 7263–7268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]