Abstract

The memory B-cell pool in an immune individual is more heterogeneous than previously recognized. The different types of memory B cells likely play distinct roles in tuning the secondary immune response because they differ in their potential to generate plasmablasts, which secrete antibodies, or germinal center (GC) cells, which generate new and higher affinity memory cells. We propose that the production of plasmablasts or GC cells by a memory B cell is controlled by its state of differentiation and the amount and affinity of antigen-specific antibodies present in the individual in which it resides.

Great Debates

What are the most interesting topics likely to come up over dinner or drinks with your colleagues? Or, more importantly, what are the topics that don't come up because they are a little too controversial? In Immune Memory and Vaccines: Great Debates, Editors Rafi Ahmed and Shane Crotty have put together a collection of articles on such questions, written by thought leaders in these fields, with the freedom to talk about the issues as they see fit. This short, innovative format aims to bring a fresh perspective by encouraging authors to be opinionated, focus on what is most interesting and current, and avoid restating introductory material covered in many other reviews.

The Editors posed 13 interesting questions critical for our understanding of vaccines and immune memory to a broad group of experts in the field. In each case, several different perspectives are provided. Note that while each author knew that there were additional scientists addressing the same question, they did not know who these authors were, which ensured the independence of the opinions and perspectives expressed in each article. Our hope is that readers enjoy these articles and that they trigger many more conversations on these important topics.

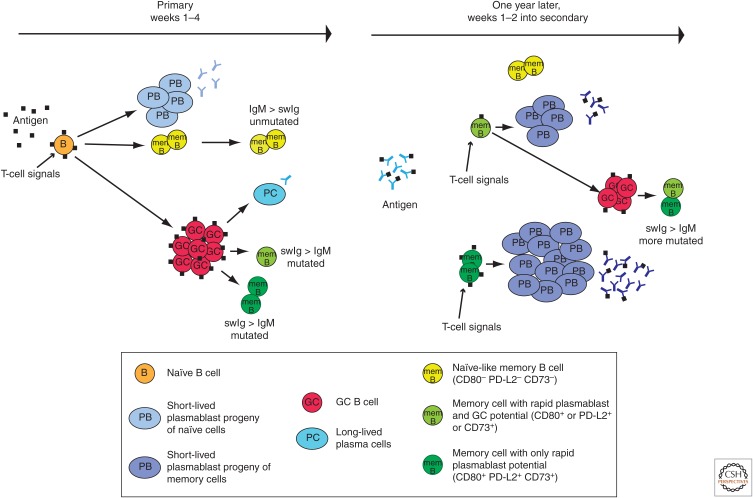

Pathogen-specific naïve B cells proliferate during primary infection in response to signals from their antigen receptors (B-cell receptors [BCRs]) and helper T cells (Fig. 1) (Kurosaki et al. 2015). The progeny of this proliferative burst differentiate into germinal center (GC) cells, memory cells, short-lived plasmablasts or long-lived plasma cells, each having a specific role in protecting the organism from the pathogen. Memory B cells play a critical role during a second infection by rapidly producing plasmablasts. The antibodies secreted by memory-cell-derived plasmablasts greatly increase the levels of circulating high-affinity antibodies (Priyamvada et al. 2016), which contribute to more rapid clearance of the pathogen. Some memory B cells, however, become GC cells during a second infection (Bende et al. 2007; McHeyzer-Williams et al. 2015). These cells are driven by antigen recognition in GCs to undergo further BCR somatic mutation and generate new memory cells, presumably with an even better capacity to protect the organism from the pathogen in the future. It is now becoming clear that the pool of memory B cells contains several subsets with different potentials to generate plasmablasts or GC cells.

Figure 1.

Speculative model for the formation of plasmablast and nonplasmablast committed memory B cells. The figure depicts the primary and secondary B-cell response to a T-cell-dependent protein antigen indicated by the small black squares. Time advances to the right in the diagram. During the primary response, signals from helper T cells and antigen-binding to the B-cell receptor (BCR) drives a naïve B cell to proliferate and produce antibody-secreting plasmablasts and germinal center (GC)-independent memory cells with unmutated and relatively low-affinity BCRs. These memory cells lack CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 and retain the capacity to produce GC cells during secondary responses, at least in the absence of antigen-clearing antibodies. GC cells form a bit later and undergo BCR somatic mutation and compete for antigen and helper T cells, and eventually generate long-lived plasma cells and two kinds of memory B cells, one expressing CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 and one expressing some but not all of these markers. The memory cells expressing CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 likely have the highest affinity BCRs and are committed to rapid production of plasmablasts during secondary responses, whereas the cells expressing some but not all of the markers likely have intermediate affinity BCRs and the potential to rapidly produce plasmablasts and later GC cells. The antigen is then cleared and a year passes, during which the memory B cells and plasma-cell-derived antibodies persist. The antigen then enters the body and much of it is immediately cleared by the existing antibodies. The limited amount of antigen prevents the GC-independent memory cells with low-affinity BCRs from responding at all. The low amount of antigen is sufficient to activate memory cells with increased BCR affinity, and these are likely to be the memory cells that express all or some of the markers. The CD80/PD-L2/CD73+ memory cells then rapidly produce plasmablasts but no GC cells, whereas the memory cells that express some of the markers form GC cells in addition to plasmabasts, eventually leading to the formation of new memory cells with more BCR mutations and higher affinity for the antigen.

MEMORY B-CELL HETEROGENEITY

It is now well established that the memory B-cell populations in both mice and humans contain subsets that express IgM or class-switched immunoglobulin (Ig) (Kurosaki et al. 2015). When generated by immunization with haptens or protein antigens and adjuvants, most class-switched Ig+ memory B cells are the affinity-matured products of the GC reaction and have varying levels of somatic mutations in their BCRs (Fig. 1). In contrast, most IgM+ memory B cells generated in this way come from a GC-independent pathway and many lack BCR mutations (Fig. 1). These are not hard and fast rules, however, because some IgM+ memory B cells have BCR somatic mutations and some class-switched Ig+ memory B cells form in the absence of GCs during certain immune responses. It is not clear why some memory B cells undergo Ig class switching, whereas others do not.

FUNCTIONS OF MEMORY B CELLS

A number of studies have attempted to define the functional differences among memory B cells. Several groups found that class-switched Ig+ memory B cells specific for protein antigens, haptens, or sheep red blood cells preferentially form plasmablasts when challenged with antigen (Benson et al. 2009; Dogan et al. 2009; Pape et al. 2011; Zabel et al. 2014; Seifert et al. 2015). In addition, class-switched Ig+ memory B cells generated plasmablasts more rapidly than naïve B cells, and did so while forming few (Pape et al. 2011; Zabel et al. 2014) or no GC cells (Benson et al. 2009; Dogan et al. 2009). These behaviors of class-switched Ig+ memory B cells are associated with enhanced Ig signaling and reduced Bach2 expression (Liu et al. 2010; Kometani et al. 2013; Seifert et al. 2015), which favor the plasmablast fate. Thus, many class-switched Ig+ memory B cells appear to be wired to provide a rapid burst of antibody-secreting plasmablasts with reduced capacity to become GC cells. These studies were consistent with the possibility that Ig class switching and memory B-cell differentiation to the plasmablast-poised state were causally related processes.

Results from three different immune responses, however, indicate that expression of other surface proteins are better predictors of memory B-cell function than Ig class switching. Shlomchik and colleagues discovered that IgM+ and class-switched Ig+ memory B-cell populations both contain additional subsets identified by expression of CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 (Anderson et al. 2007; Tomayko et al. 2010). In a study by Pape and colleagues (2011), the memory B-cell population induced by immunization with the protein antigen phycoerythrin in complete Freunds adjuvant (CFA) consisted of IgM+ and class-switched Ig+ subsets. Almost all of the IgM+ memory cells lacked CD80 and CD73 and produced plasmablasts and abundant GC cells with the relatively slow kinetics of naïve cells after exposure to antigen in adoptive hosts. In contrast, almost all of the class-switched Ig+ memory cells expressed CD80 and CD73 and rapidly produced plasmablasts and later only a small population of GC cells. Thus in this system, CD80 expression and Ig class switching were both good predictors of the plasmablast-poised state of differentiation. Shlomchik and colleagues (Zuccarino-Catania et al. 2014) also found that a hapten-specific memory B-cell population induced by immunization with hapten-chicken IgG in alum consisted of IgM+ and class-switched Ig+ subsets. The class-switched Ig+ subpopulation consisted of 70% CD80+ PD-L2+ cells, 20% that expressed one of the markers and 10% that lacked both markers. This mixed population produced abundant plasmablasts early and no GC cells after exposure to antigen in adoptive hosts. Thus, as in the phycoerythrin system, the class-switched Ig+ memory cell subset was dominated by plasmablast-poised CD80+ cells, most of which could not produce GC cell progeny. The IgM+ subpopulation consisted of 27% CD80+ PD-L2+ cells, 27% that expressed one of the markers, and 46% that lacked both markers. Isolated CD80+ PD-L2+ IgM+ cells rapidly produced abundant plasmablasts and no GC cells after exposure to antigen, whereas IgM+ cells that expressed one or none of the markers produced plasmablasts and GC cells. Thus, CD80+ PD-L2+ IgM+ cells were poised to rapidly generate plasmablasts like their class-switched Ig+ counterparts. Similarly, Pepper and colleagues (Krishnamurty et al. 2016) recently showed that a sizeable subset of malaria antigen-specific IgM+ memory cells expressed CD80 and CD73 and rapidly formed plasmablasts after stimulation by antigen. Together the results from these different systems suggest that the recall potential of memory B cells for rapid plasmablast production at the expense of GC cell generation scales with the amount of CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 expression. A challenge to the field now is to identify the signals that commit memory B cells to these different states of differentiation.

The existence of memory B cells that can generate GC progeny is consistent with several other observations. Broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) envelope-specific antibodies with a large number of somatic mutations are likely the progeny of memory B cells that iteratively generate GC cells during persistent or sequential infections (Mascola and Haynes 2013; Victora and Wilson 2015). In addition, a recent study from McHeyzer-Williams and colleagues (2015) identified a population of class-switched Ig+ memory B cells that reentered GCs after antigen challenge and further diversified their BCRs. The studies described in the preceding paragraphs suggest that these memory B cells were in the intermediate differentiation state defined by expression of some but not all of the CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 markers.

ANTIBODIES SUPPRESS THE GC CELL FATE

Another important factor that influences the behavior of memory B cells during secondary immune responses is the presence of high-affinity antigen-specific Ig. Injection of hyperimmune serum containing antigen-specific Ig, or class-switched Ig+ memory B cells that rapidly produce plasmablasts and antibodies, inhibits naïve antigen-specific B cells (Pape et al. 2011) from becoming GC cells after immunization. This is likely caused by high-affinity antibodies rapidly reducing the amount of available antigen, thereby preventing the newly responding B cells, which have BCRs of lower affinity, from responding for long enough to become GC cells. IgM+ memory B cells induced by immunization with a protein antigen and lacking CD80 and CD73 also respond poorly after secondary exposure to antigen in mice containing high titers of antigen-specific antibodies (Fig. 1) (Pape et al. 2011; Zabel et al. 2014), again likely because of rapid antigen clearance. Class-switched Ig+ memory B cells with higher affinity BCRs and expressing CD80 and CD73 can still bind antigen under these conditions and this binding triggers mainly plasmablast formation (Fig. 1). Toellner and colleagues (Zhang et al. 2013) also studied this issue by injecting antigen-specific monoclonal antibody–antigen complexes of increasing affinity into immunized mice. When the affinity of the injected antibody was high enough, GC T–B interactions and memory B-cell output were suppressed, suggesting that the high-affinity antibodies out-competed the GC B cells for access to antigen. We speculate that the action of high-affinity antibodies to limit the GC potential of CD80/PD-L2/CD73− memory cells and the intrinsic tendency of CD80/PD-L2/CD73+ memory cells to form plasmablasts creates the situation in which plasmablasts are the dominant progeny of memory cells during many secondary immune responses.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

We propose that the answer to the title question, “Do memory B cells form secondary germinal centers?” is “yes” for memory B cells that do not achieve the fully differentiated state defined by expression of CD80, PD-L2, and CD73. However, we think that the least-differentiated memory B cells within this category, mainly those derived from the GC-independent pathway, only rarely realize this potential during secondary responses because of an inability to access antigen in the face of high-affinity serum antibodies (Fig. 1). In addition, we think it is likely that the memory cells that express CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 cannot form secondary GC cells (Fig. 1). Thus, we propose that the main contributors of GC cells during secondary responses are memory B cells that express some but not all of the CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 markers (Fig. 1).

The answer to the title question has implications for the design of vaccination strategies that can efficiently generate broadly neutralizing HIV envelop-specific antibodies. The known antibodies that have this capacity have a remarkably large number of somatic mutations, many more than are normally found in antibodies generated by a single vaccination (Kwong et al. 2013). It is, therefore, likely that an effective vaccine strategy will depend on multiple rounds of vaccination and the generation of memory B cells at each round that can produce new GC cell progeny. This strategy must ensure that the memory B cells induced by the first vaccination have high enough affinity BCRs to compete with antigen-clearing antibodies. And these memory B cells must not be immediately driven to the plasmablast-poised CD80/PD-L2/CD73+ state, thereby preventing GC cell production at each subsequent boost. The optimal protocol may thus depend on the generation of memory B cells in the intermediate differentiation state defined by expression of some but not all of the CD80, PD-L2, and CD73 markers. It will, therefore, be important to gain a better understanding of the factors that control somatic mutation and memory B-cell subset differentiation. In the meantime, it makes sense to limit plasmablast and antibody production at each round of vaccination to minimize antigen clearance and prolong the GC reaction for any memory B cells that retain GC cell production potential. One strategy to achieve this end would be to bracket each round of vaccination with mTOR kinase-inhibiting drugs, which block plasmablast formation while enhancing Ig class-switch recombination (Limon et al. 2014).

Footnotes

Editors: Shane Crotty and Rafi Ahmed

Additional Perspectives on Immune Memory and Vaccines: Great Debates available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Anderson SM, Tomayko MM, Ahuja A, Haberman AM, Shlomchik MJ. 2007. New markers for murine memory B cells that define mutated and unmutated subsets. J Exp Med 204: 2103–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bende RJ, van Maldegem F, Triesscheijn M, Wormhoudt TA, Guijt R, van Noesel CJ. 2007. Germinal centers in human lymph nodes contain reactivated memory B cells. J Exp Med 204: 2655–2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MJ, Elgueta R, Schpero W, Molloy M, Zhang W, Usherwood E, Noelle RJ. 2009. Distinction of the memory B cell response to cognate antigen versus bystander inflammatory signals. J Exp Med 206: 2013–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan I, Bertocci B, Vilmont V, Delbos F, Megret J, Storck S, Reynaud CA, Weill JC. 2009. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effector functions. Nat Immunol 10: 1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kometani K, Nakagawa R, Shinnakasu R, Kaji T, Rybouchkin A, Moriyama S, Furukawa K, Koseki H, Takemori T, Kurosaki T. 2013. Repression of the transcription factor Bach2 contributes to predisposition of IgG1 memory B cells toward plasma cell differentiation. Immunity 39: 136–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurty AT, Thouvenel CD, Portugal S, Keitany GJ, Kim KS, Holder A, Crompton PD, Rawlings DJ, Pepper M. 2016. Somatically hypermutated plasmodium-specific IgM+ memory B cells are rapid, plastic, early responders upon malaria rechallenge. Immunity 45: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T, Kometani K, Ise W. 2015. Memory B cells. Nat Rev Immunol 15: 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. 2013. Broadly neutralizing antibodies and the search for an HIV-1 vaccine: The end of the beginning. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 693–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limon JJ, So L, Jellbauer S, Chiu H, Corado J, Sykes SM, Raffatellu M, Fruman DA. 2014. mTOR kinase inhibitors promote antibody class switching via mTORC2 inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: E5076–E5085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Meckel T, Tolar P, Sohn HW, Pierce SK. 2010. Intrinsic properties of immunoglobulin IgG1 isotype-switched B cell receptors promote microclustering and the initiation of signaling. Immunity 32: 778–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascola JR, Haynes BF. 2013. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies: Understanding nature's pathways. Immunol Rev 254: 225–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Milpied PJ, Okitsu SL, McHeyzer-Williams MG. 2015. Class-switched memory B cells remodel BCRs within secondary germinal centers. Nat Immunol 16: 296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, Gearhart PJ, Jenkins MK. 2011. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science 331: 1203–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyamvada L, Cho A, Onlamoon N, Zheng NY, Huang M, Kovalenkov Y, Chokephaibulkit K, Angkasekwinai N, Pattanapanyasat K, Ahmed R, et al. 2016. B cell responses during secondary Dengue virus infection are dominated by highly cross-reactive, memory-derived plasmablasts. J Virol 90: 5574–5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert M, Przekopowitz M, Taudien S, Lollies A, Ronge V, Drees B, Lindemann M, Hillen U, Engler H, Singer BB, et al. 2015. Functional capacities of human IgM memory B cells in early inflammatory responses and secondary germinal center reactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112: E546–E555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomayko MM, Steinel NC, Anderson SM, Shlomchik MJ. 2010. Cutting edge: Hierarchy of maturity of murine memory B cell subsets. J Immunol 185: 7146–7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora GD, Wilson PC. 2015. Germinal center selection and the antibody response to influenza. Cell 163: 545–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel F, Mohanan D, Bessa J, Link A, Fettelschoss A, Saudan P, Kundig TM, Bachmann MF. 2014. Viral particles drive rapid differentiation of memory B cells into secondary plasma cells producing increased levels of antibodies. J Immunol 192: 5499–5508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Meyer-Hermann M, George LA, Figge MT, Khan M, Goodall M, Young SP, Reynolds A, Falciani F, Waisman A, et al. 2013. Germinal center B cells govern their own fate via antibody feedback. J Exp Med 210: 457–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccarino-Catania GV, Sadanand S, Weisel FJ, Tomayko MM, Meng H, Kleinstein SH, Good-Jacobson KL, Shlomchik MJ. 2014. CD80 and PD-L2 define functionally distinct memory B cell subsets that are independent of antibody isotype. Nat Immunol 15: 631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]