Abstract

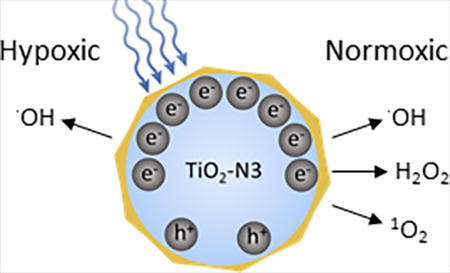

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is widely used to treat diverse diseases, but its dependence on oxygen to produce cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) diminishes the therapeutic effect in a hypoxic environment such as solid tumors. Here, we developed a ROS-producing hybrid nanoparticle-based photosensitizer capable of maintaining high levels of ROS under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Conjugation of an organometallic ruthenium complex (N3) to a TiO2 nanoparticle afforded TiO2-N3. Upon exposure of TiO2-N3 to light, the N3 injected electrons into TiO2 to produce three- and four-fold greater hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide, respectively, than TiO2 at 160 mmHg. TiO2-N3 maintained three-fold higher hydroxyl radicals than TiO2 under hypoxic conditions via N3-facilitated electron hole reduction of adsorbed water molecules. The incorporation of N3 transformed TiO2 from a dual type I and II PDT agent to a predominantly type I photosensitizer, irrespective of the oxygen content.

Keywords: nanophotosensitizer, TiO2, reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, organometallic ruthenium complex

COMMUNICATION

A dual type I and type II PDT agent, titanium dioxide-ruthenium nano-photosensitizer (TiO2-N3) synergistically produced hydroxyl radicals under both hypoxic and normoxic conditions.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are products of normal metabolic processes in living organisms. At low concentrations, these species play vital roles in cell signaling, but they can become cytotoxic at elevated levels via reaction with proteins, DNAs, lipids, and other biological molecules. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a treatment paradigm that selectively elevates ROS levels to induce cell death by multiple pathways.[1] Some molecules, known as photosensitizers (PSs), absorb light of the appropriate wavelengths to produce cytotoxic free radicals and ROS. Many organic PSs mainly produce singlet oxygen (1O2) formed via spin inversion of triplet oxygen to singlet oxygen (type II PDT).[2] Specific organic PSs can also produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl (•OH) radicals, formed from direct ionization events (type I PDT).[2] While the highly reactive •OH and 1O2 rapidly interact with adjacent biomolecules to disrupt normal cell functions and induce cell death, the more stable H2O2 can travel across cell membranes.[3] Intracellular scavengers, such as catalases or peroxidases can convert H2O2 to superoxide radicals.[4] However, ferrous ions can rapidly oxidize H2O2 to reactive •OH radicals (Fenton reaction) to enhance the PDT effect, especially in tumor cells where the increased demand for iron is high.[5] Despite these advantages, the reliance of many organic PSs on molecular oxygen limits the effectiveness of PDT in hypoxic environments, which include many solid tumors.[6] During PDT, local oxygen is rapidly consumed, creating transient hypoxia that further decreases the therapeutic effects.[7] Moreover, most organic PSs can react with 1O2 produced during PDT, leading to a depletion of the PSs’ concentration via a photobleaching process.[8] As a result, a recent trend in PDT research includes the development of new PSs that are capable of producing cytotoxic ROS, irrespective of the oxygenation status of the microenvironment.

Some studies have shown that organometallic PSs can damage DNA under normoxic and hypoxic conditions.[9] One of such complexes is cis-bis(isothiocyanato)bis(2,2’-bipyridyl-4,4’-dicarboxylato)ruthenium(II), abbreviated N3. This complex, which absorbs light in the UV and visible wavelengths, possesses multiple triplet states that can be populated by both metal to ligand charge transfer (3MLCT) and intra-ligand charge transfer (3π−π*) mechanisms.[10] Organometallic PSs have long triplet state lifetimes (~ms) that enhances the interaction with oxygen species and subsequent ROS production.[11] Although N3 can produce damage regardless of molecular oxygen content, metal oxides such as TiO2 produce higher amounts of ROS in the presence of oxygen. The excitation of TiO2 with radiative energy greater than its band gap of 3.2 eV (387 nm) promotes an electron to the conduction band, creating an electron hole pair.[12] The electrons primarily reduce adsorbed molecular oxygen to superoxide, and the holes largely oxidize substrates such as water into a hydrogen ion and an •OH.[12] These processes allow TiO2 to produce higher amounts of diverse ROS compared to traditional small molecule PS, making TiO2 a viable PDT agent. However, hypoxic conditions significantly deplete the amount of ROS that TiO2 forms.

In this study, we synthesized TiO2-N3 nanoparticles, consisting of a regenerative ROS-producing TiO2 core that is coated with N3 to enhance ROS production at different levels of oxygen pressure. TiO2 materials are excellent electron acceptors from organometallic ruthenium complexes, a phenomenon that has been used for converting sunlight into current.[13] By coating the surface of TiO2 nanoparticles with N3, each ruthenium complex can inject an electron into TiO2, building up electrons that increase ROS production.[12, 13b, 14] TiO2 is widely considered biologically inert and toxicity studies conducted in tumor bearing mice demonstrate limited dark toxicity.[13e] Similarly, toxicity studies with organometallic ruthenium complexes have also been conducted in tumor cells and mice, and show limited toxicity.[9b]

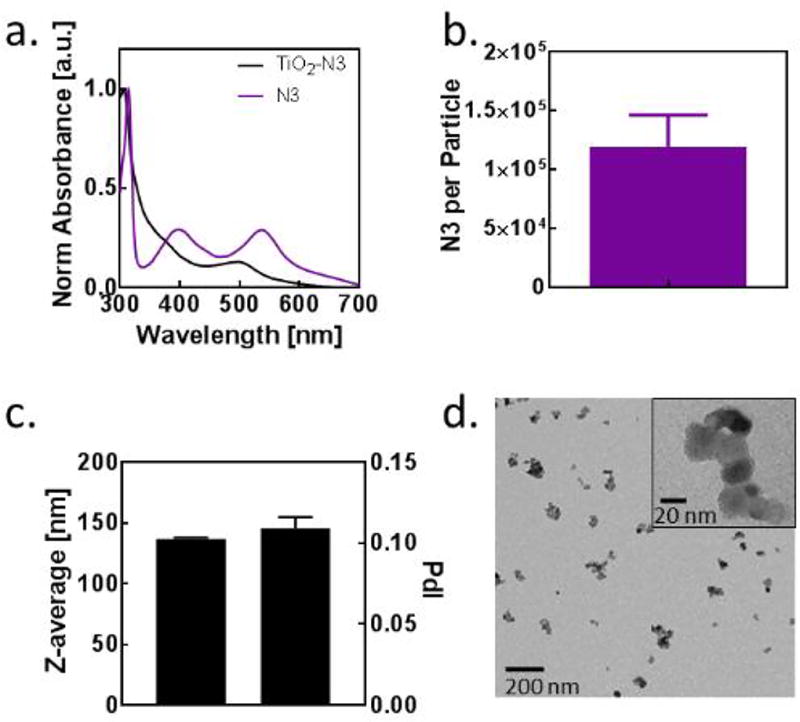

TiO2-N3 nanoparticles were prepared by shaking a mixture of 25 nm sized anatase TiO2 particles and N3 in an ethanol overnight. The particles were then centrifuged and the supernatant discarded, followed by the addition of water to the residue. Subsequent sonication (45 seconds) dispersed and evenly coat the particles. Filtration through a 0.45 um pore removed large aggregates. The absorption spectra of N3 blue-shifts when coated on TiO2, suggesting that TiO2 increased the excited state energies of the N3 (Figure 1a). The TiO2-N3 particles contain an average of 125,000 N3 molecules per nanoparticle (Figure 1b) with an average hydrodynamic size of 135 nm based on dynamic light scattering measurement (Figure 1c). Transmission electron microscopy of TiO2-N3 showed that the 25 nm TiO2 cores were maintained in the 135 nm clusters (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Characterization of TiO2-N3 nanoparticles. (a) Absorption spectra for N3 and TiO2-N3. (b) Number of N3 incorporated into a 25 nm TiO2 particle. (c) Average size of TiO2-N3 particles after sonication and filtering. (d) Transmission electron microscopy of TiO2-N3 particles with zeta potential of +11.2 +/− 0.6 mV.

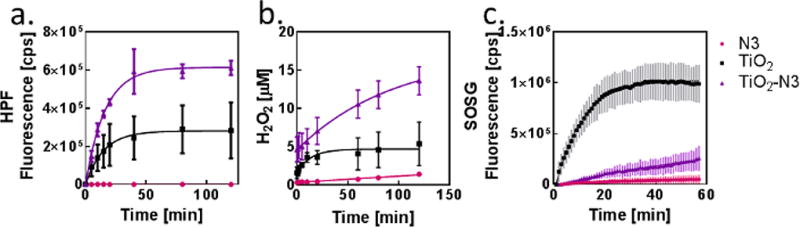

To determine the ROS produced by TiO2-N3, bare TiO2, and N3, we used hydroxyphenyl fluorescein (HPF), singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG), and Amplex Red assay for •OH, 1O2, and H2O2, respectively. For these assays TiO2-N3 was not sonicated or filtered. A solution of 10 µM HPF or SOSG and PS (0.1 mg/mL TiO2, 0.1 mg/mL TiO2-N3, or 7 µM N3) was irradiated at 1.69 mW/cm2 using a 365 nm light source. For •OH, measurements, aliquots of 100 µL of HPF were diluted in Tris buffer (pH 8.0; 900 µL) at different time points (Figure 2a) and the fluorescence of each sample was measured at ex/em 478/515 nm. 1O2 measurements were accomplished by irradiating SOSG in a quartz cuvette continuously for 60 min and the fluorescence was measured every 1 min (ex/em 504/525 nm). H2O2 measurements were performed in a 96 well plate (50 µL) using the same concentrations of each PS as above and an irradiation power of 2.39 mW/cm2. The fluorescence at ex/em 545/590 nm and a reference standard were used to calculate the concentration of H2O2 in each well. To quantify the amount of the different types of ROS produced, each activation curve was fitted to an exponential plot (Figure 2a–c).

Figure 2.

ROS production and characterization. Time course of (a) hydroxyl radical, (b) hydrogen peroxide, and (c) singlet oxygen production, respectively, as PSs are irradiated with 365 nm light.

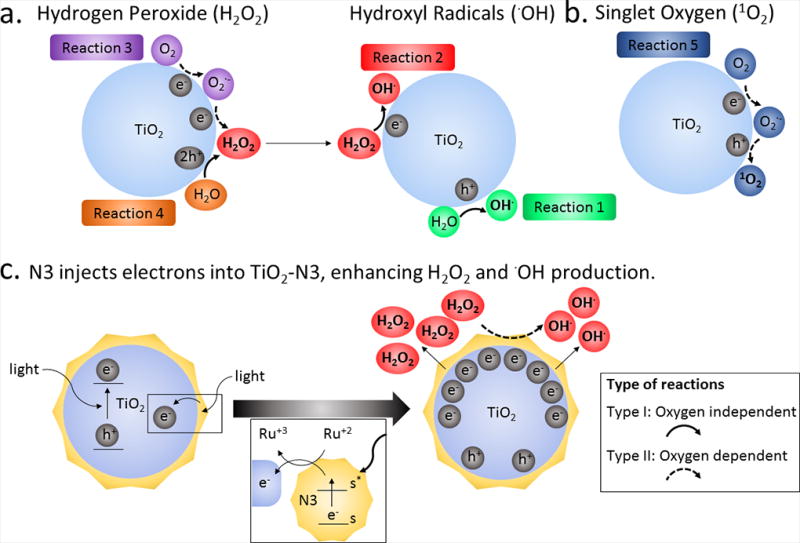

Scheme 1 illustrates the different pathways to generate ROS (•OH, H2O2, and 1O2) from TiO2-N3. Under normal oxygen pressure (160 mmHg), the photo-activation of TiO2-N3 resulted in bout 3-fold higher •OH production compared to TiO2 and N3 (Figure 2a). These radicals could be produced by two mechanisms. Reaction 1 is a one-step oxidation of water to a •OH, a primary pathway used by bare TiO2 nanoparticles (Scheme 1a). The observed increase in •OH suggested the involvement of another mechanism, Reaction 2, which reduces a precursor H2O2 to an •OH. Two pathways are available for H2O2 formation (Scheme 1b). In Reaction 3, two conduction band electrons from TiO2 are used to first reduce oxygen to superoxide, which is subsequently reduced to H2O2. In the second mechanism, Reaction 4, two holes on the TiO2 nanoparticles oxidize adsorbed water molecules to H2O2. The complementary molecular oxygen dependent (Reaction 3) and independent (Reaction 4) pathways to produce H2O2 ensures the generation of hydroxyl radicals. The bare TiO2 particles probably rely more on Reaction 1 than 2 for •OH production because of the direct oxidation of abundant water molecules. Alternatively, the TiO2 in TiO2-N3 has higher numbers of conduction band elections due to the injection of electrons from photo-activated N3. This process creates more electrons for Reactions 3 and 2, accounting for the observed 3-fold increase in the •OH produced (Scheme 1d).

Scheme 1.

Schematic description of ROS generation by TiO2 and electron injection to TiO2 by N3, not drawn to scale.

We next postulated that the high •OH levels in TiO2-N3 are associated with a corresponding increase in H2O2 production. Upon photoactivation, TiO2-N3 generated about 4-fold higher H2O2 than TiO2 (Figure 2b). The low yield of H2O2 from N3 indicates that its contribution to •OH production was minimal. These results support a mechanism where N3 injected electrons into TiO2 to increase the conversion of oxygen to H2O2 via Reaction 3 and a rapid transformation of H2O2 to •OH through Reaction 2.

The other reactive ROS, 1O2, is the primary species involved in oxygen dependent type II PDT. The ease of electron–hole pair generation upon exposure of TiO2 nanoparticles to light, facilitates concerted reduction of oxygen to super oxide and subsequent oxidation to 1O2 (Scheme 1c). Expectedly, our results show that TiO2-generated 1O2 was an order of magnitude higher than TiO2-N3 or N3 (Figure 2c). In contrast to the synergistic effects of N3 on •OH and H2O2 production by TiO2-N3, N3 effectively inhibited 1O2 generation. Alone, N3 can produce singlet oxygen through intersystem crossing to the triplet state and spin-inversion of the triplet state of N3 and triplet state of oxygen. Whereas this process takes place on the time scale of microseconds,[11] electron injection into TiO2 occurs on the time scale femtoseconds.[15] As a result, when N3 is adsorbed onto TiO2, the probability of electron injection is higher than intersystem crossing and spin-inversion. Thus, N3 favors reduction reactions, which enhances H2O2 production that is subsequently used to increase •OH. Effectively, N3 converts TiO2 from a dual type I and II PDT agent to a predominantly type I PS under normoxic conditions.

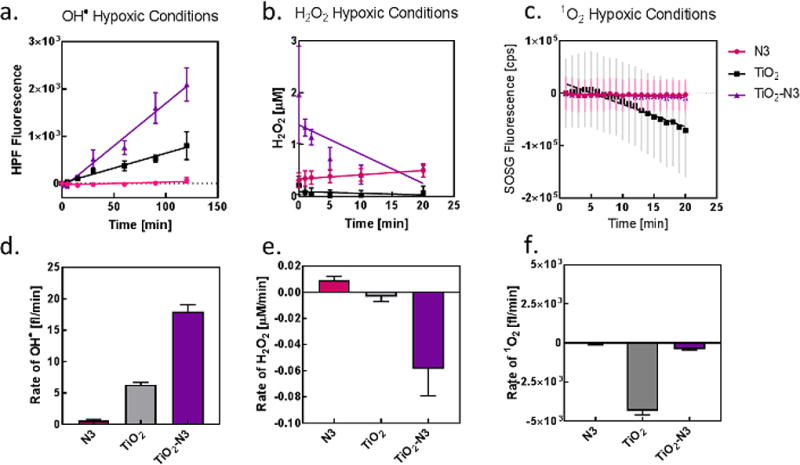

To test the performance of the PSs under severe hypoxic conditions, we bubbled nitrogen in a suspension of the PSs and the appropriate sensors to attain 8 mmHg, the average partial pressure of oxygen in hypoxic tumors, for all ROS measurements.[16] For H2O2 and •OH measurements, the solution was then added to a 96-well plate and incubated in 8 mmHg oxygen pressure atmosphere for an hour. Measurements were taken at different time points after UV irradiation of the solution (Figure 3). We found that the •OH production followed the same trend as in normoxic conditions, with TiO2-N3 generating about 3-fold greater •OH than either TiO2 or N3 (Figure 3a). In addition, the rate of •OH production for TiO2-N3 was 3-fold higher than TiO2. These results demonstrate that the reductive effect of N3 on TiO2 allowed the efficient utilization of oxygen, even at low pressures, to maintain •OH production (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Oxygen dependence on hydroxyl radical production. ROS production of (a) hydroxyl radical, (b) hydrogen peroxide, and (c) singlet oxygen at 8 mmHg oxygen pressure. Rate of (d) hydroxyl radical, (e) hydrogen peroxide, and (f) singlet oxygen production under hypoxic conditions.

N3 was the only PS that generated H2O2 in hypoxic conditions (Figure 3b, e). The slopes of H2O2 generation for TiO2 and TiO2-N3 were both negative in hypoxic conditions, indicating a decrease in baseline H2O2 over time. The dependence of the initial on the reduction of oxygen reaction to produce H2O2 led to the observed effect for TiO2 or TiO2-N3 (Reaction 3). Irrespective of the PS used, the minimal availability of molecular oxygen under hypoxic conditions prevented the production of 1O2 (Figure 3c, f).

This work demonstrates that combining the two PSs resulted in changes to their photophysical properties, which altered both the type and amount of ROS produced. It also delineates the various pathways that TiO2-N3 uses to enhance •OH production and maintain a significant level of these species in normoxic and hypoxic conditions. The addition of N3 to TiO2 causes a build-up of electrons on the TiO2 surface, which likely accounts for the synergistic production of H2O2 and •OH (Figure 2 a, b and Scheme 1d). Furthermore, the inability of TiO2 to produce H2O2 under hypoxic conditions suggests that N3 facilitated the depletion of residual H2O2 (Figure 3b, e) and the rapid conversion of the low oxygen concentration into •OH, thus increasing the concentration of this species (Figure 3a, d). The ensemble of these results demonstrates a mechanism to convert and maintain cytotoxic •OH production by harnessing the reductive power of ruthenium complexes, which efficiently reduces low levels of oxygen for ROS production. The limited penetration of light in tissue precludes the routine use of these UV-absorbing materials for treating lesions deeper than a few microns from the light source. However, a recent work demonstrating the use of Cerenkov radiation from radionuclides as tissue-depth independent light source for PDT suggests the potential use of TiO2-N3 nanoparticles for whole-body treatment of localized and disseminated disease.[13e] Our findings could enable the application of this strategy to develop highly efficient nano-photosensitizers in the future for PDT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

R.C.G. was partly supported by the Mr. and Mrs. Spencer T. Olin Fellowship for Women in Graduate Study. This research was supported in part by NIH grants (U54 CA199092, R01 EB021048, R01 CA171651, P50 CA094056, P30 CA091842, S10 OD016237, S10 RR031625, and S10 OD020129), the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-16-1-0286), and the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Research Fund (11-FY16-01).

References

- 1.Castano AP, Mroz P, Hamblin MR. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:535–545. doi: 10.1038/nrc1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolmans EJGJD, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:380–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher AB. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;6:1349–1356. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halliwell B. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1996;16:33–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torti SV, Torti FM. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:342–355. doi: 10.1038/nrc3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Hardee ME, Dewhirst MW, Agarwal N, Sorg BS. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009;9:435–441. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Maxwell PH, Dachs GU, Gleadle JM, Nicholls LG, Harris AL, Stratford IJ, Hankinson O, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997;94:8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Mitra S, Foster T. Neoplasia. 2008;10:429–438. doi: 10.1593/neo.08104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Celli JP, Spring BQ, Rizvi I, Evans CL, Samkoe KS, Verma S, Pogue BW, Hasan T. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2795–2838. doi: 10.1021/cr900300p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Obaid G, Broekgaarden M, Bulin AL, Huang HC, Kuriakose J, Liu J, Hasan T. Nanoscale. 2016;8:12471–12503. doi: 10.1039/c5nr08691d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potter WR, Mang TS, Dougherty TJ. Photochem. and Photobiol. 1987;46:97–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Sun Y, Joyce LE, Dickson NM, Turro C. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:2426–2428. doi: 10.1039/b925574e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shi G, Monro S, Hennigar R, Colpitts J, Fong J, Kasimova K, Yin H, DeCoste R, Spencer C, Chamberlain L, Mandel A, Lilge L, McFarland SA. Coor. Chem. Rev. 2015;282–283:127–138. [Google Scholar]; c) Lv W, Zhang Z, Zhang KY, Yang H, Liu S, Xu A, Guo S, Zhao Q, Huang W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:9947–9951. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fantacci S, De Angleis F, Selloni A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4008–4400. doi: 10.1021/ja0207910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincoln R, Kohler L, Monro S, Yin H, Stephenson M, Zong R, Chouai A, Dorsey C, Hennigar R, Thummel RP, McFarland SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:17161–17175. doi: 10.1021/ja408426z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nosaka Y, Nosaka AY. In: Photocatalysis and Water Purification: From Fundamentals to Recent Applications. Pichat P, editor. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim, Germany: 2013. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) O’Regan B, Grätzel M. Nature. 1991;353:737–741. [Google Scholar]; b) Katoh R, Furube A, Yoshihara T, Hara K, Fujihashi G, Takano S, Murata S, Arakawa H, Tachiya M. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;108:4848–4852. [Google Scholar]; c) He YL, Wang S, Zhang L, Xin J, Wang J, Yao C, Zhang Z, Yang CC. J. Biomed. Opt. 2016;21:1–9. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.21.12.128001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Dimitrijevic NM, Rozhkova E, Rajh T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2893–2899. doi: 10.1021/ja807654k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kotagiri N, Sudlow GP, Akers WJ, Achilefu S. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015;10:370–379. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Abdellah M, El-Zohry AM, Antila LJ, Windle CD, Reisner E, Hammarstrom L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1226–1232. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ashford DL, Song W, Concepcion JJ, Glasson CR, Brennaman MK, Norris MR, Fang Z, Templeton JL, Meyer TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19189–19198. doi: 10.1021/ja3084362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asbury JB, Hao E, Wang Y, Ghosh HN, Lain T. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:4545–4552. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hockel M, Vaupel P. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001;93:266–267. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.