Abstract

Objective:

The objective of the study was to find the weight reduction pattern and its outcome on knee pain and function in osteoarthritis (OA) morbidly obese patients’ post-bariatric surgery with dietary and exercise changes.

Methodology:

Thirty morbidly obese (body mass index [BMI] >40 kg/m2) OA patients gave consent for bariatric surgery. Despite wearisome lifestyle modifications for weight loss and knee pain, satisfactory results were not retrieved. We took consent from all the patients predetermined for knee replacement in future because of pain and disability as recommended by knee replacement surgeon. The dietary and exercise protocol was standardised for all patients for bariatrics. Data for weight loss, change in BMI and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index score consisting of pain, stiffness and activities of daily livings (ADLs) scores were documented at baseline, 3 months and 6 months post-bariatric surgery.

Results

The male-to-female ratio was 1:2. Mean age of the patients was 49.8 ± 8.6 years. Significant changes in pain (P < 0.001), stiffness (P < 0.001) and ADLs (P < 0.001) were found postoperatively at 3 and 6 months. Positive correlation of percentage change of BMI was seen with percentage change in pain (r = 0.479, P = 0.007) and ADLs (r = 0.414, P = 0.023) after 6 months of bariatric surgery. Most of the patients were inclined to delay the knee replacement further by the end of 6 months post-bariatric surgery.

Conclusion:

Bariatric surgery when combined with dietary and exercise changes gave significant results in terms of weight loss, knee pain and function. It is an approach that tackles both obesity and OA. It is a major step forward in stemming the global epidemic of these two interlinked conditions.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, obesity, osteoarthritis, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index

INTRODUCTION

Obesity and overweight are considered to be the fifth leading risk factor for deaths worldwide, and at least 2.8 million adults die each year as a result of chronic conditions associated with excess body weight in both more and less developed countries.[1] Morbid obesity is associated with a number of co-morbidities that considerably affect the patient's health. This includes diabetes, dyslipidaemia, obstructive sleep apnoea, hypertension and joint pain of knee and back,[2] but the combination of obesity with diabetes has been increased with alarming rate in recent years and became a common problem globally including developing and developed countries with incalculable social costs.[3] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), individuals with body mass index (BMI) above 30 kg/m2 are obese and those above 40 kg/m2 are considered morbidly obese.[2] The WHO estimates that currently more than 1 billion people are overweight and amongst them 300 million are obese.[3]

Obesity is one of the leading[4] and greatest modifiable[5] risk factors for the development of osteoarthritis (OA). It is a progressive degenerative disorder that leads to joint damage, chronic pain, muscle atrophy, decreased mobility, poor balance and eventually physical disability.[6] Arthritis is becoming pandemic globally and its presence with obesity and diabetes is being observed more commonly than ever.[3] Prevalence of OA in India is reported to be in the range of 17%–60.6%.[7] Individuals with clinically defined obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) are four times more likely to have knee OA than those with normal BMI (<25 kg/m2).[4] According to King et al.'s study, a five-unit increase in BMI was associated with 35% increase risk of knee OA.[5] Holliday et al. found that those who became overweight early in adulthood showed higher risk of lower limb OA.[8]

A study found that patients with OA who lose weight may see improvement in their OA symptoms.[5] An observational evidence from the Framingham OA study shows that a reduction in weight of around 5 kg decreases the risk of developing knee OA by more than 50% in women with a baseline BMI >25.[9] Messier et al. used various combinations of diet and exercises weight reduction process in their study and found that both when used together produced significant improvements.[6] The conventional conservative treatments available such as diet, exercise and medication are found ineffective in maintaining uniform weight loss.

With increased prevalence of obesity, a need for joint replacement surgery found to be escalated.[5] It is a surgical procedure where the diseased knee joint surfaces are replaced with metal or plastic components to relieve pain and restore knee function. Total knee replacement (TKR) is a highly prevalent and expensive surgical procedure. Although TKR helps in reducing pain in most patients, it does not resolve many of functional limitations associated with chronic knee arthritis that existed before the surgery.[10] A study found that patients with BMI >35 kg/m2 had persistent pain even after TKR.[11] A Canadian prospective observational study in 520 patients who have undergone total knee and hip replacement for evaluating obesity effects found obesity a risk factor for slow recovery over 3 years.[12]

Bariatric surgery came as a boon for the obese persons as it helps in the gradual loss of excess body weight of about 60%–70%.[13] It promotes weight loss by changing the digestive system's anatomy, limiting the amount of food. It is a tool towards healthier life and not simply a means of weight loss. Other than remission of hypertension and type 2 diabetes (50% and 38%) in a systematic review and meta-analysis post-bariatric patients,[14] bariatric surgery simultaneously has also worked solely in reducing symptoms of knee pain in OA patients in a study by Edwards et al.[4]

Furthermore, according to American College of Rheumatology, an average weight loss of 5% over a period of 18 months in overweight and obese adults with knee OA results in an 18% improvement in function but when dietary changes were combined with exercises, function improved by 24% along with significant improvement in the symptoms associated with knee OA.[15]

Thus, we hypothesised that weight loss through bariatric surgery when combined with dietary and exercise changes would give highly significant results in terms of both weight reduction and knee pain in overweight and morbidly obese OA patients making a way to delay the need for knee replacement.

METHODOLOGY

A total of thirty out of forty morbidly obese (BMI >40 kg/m2) patients with OA (Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) Grade IV) gave consent for bariatric surgery. Despite wearisome lifestyle modifications for weight loss and knee pain, satisfactory results were not retrieved in all the thirty patients. Consent from all the patients predetermined for knee replacement in future because of pain and disability as recommended by knee replacement surgeon were taken. The dietary and exercise protocol was standardised for all patients opting for bariatric. Inclusion criteria include age group 25–75 years, BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and unilateral/bilateral knee OA (KL Grade IV). Patients who already took corticosteroid injection on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), viscosupplementation, who suffered fracture recently of lower limb and cognitive impairment were excluded from the study. Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), a standardised self-administered questionnaire, was used to evaluate both development and progression of OA. It comprises 24 questions (5 - pain, 2 - stiffness and 17 - physical functioning). WOMAC score was taken at baseline, 3 months and after 6 months of follow-up. The types of bariatric surgery performed were laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG-12), mini gastric bypass (MGB-12) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB-6). Demographic data such as age, height, weight and BMI were noted as baseline. Post-surgery diet protocol as per registered dietician was given. A fixed 5-exercise protocol for knee OA with Mulligan mobilisation was formed by bariatric physiotherapist (LR) that also included fixed ambulation in whole day both pre and postoperatively with proper knee cap and sports shoes mandatory.

Statistical analysis

MedCalc (Demo Version) Software (Belgium) was used for the analysis. A two-tailed (α = 2) probability P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; P ≤ 0.05 as highly significant and P > 0.05 had no significance. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to find the change in weight, BMI and WOMAC score. Spearman's rank correlation analysis was used to compare percentage change in WOMAC parameters (pain, stiffness and activities of daily livings [ADLs]) with respect to percentage change in BMI. Type of surgeries was also compared to find which type of surgery was most effective.

RESULTS

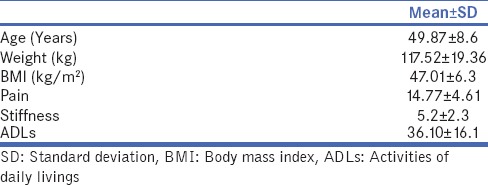

Out of forty patients, the study was completed with thirty (20 females and 10 males) patients who met our inclusion criteria. Demographic data include mean age of patients was 50 years, average pre-operative weight was 117.52 kg and BMI 47.01 kg/m2 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

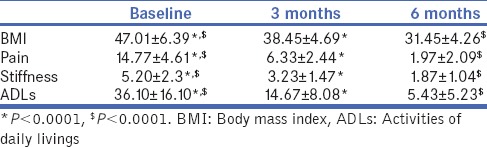

As a result of bariatric surgery, there is as significant reduction in weight and BMI after 3 and 6 months postoperatively (P < 0.0001) [Table 2]. There was also a significant reduction in pain, stiffness and ADL after 3 and 6 months postoperatively [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparing average body mass index, pain, stiffness and activities of daily livings (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) at baseline, 3 months and 6 months post-bariatric surgery

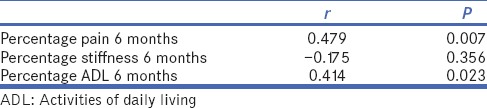

Significant correlation of percentage change in BMI with percentage change of pain (r = 0.479, P = 0.007) and ADL (r = 0.414, P = 0.023) was observed. However, no correlation was seen with percentage stiffness change (r = −0.175, P = 0.356) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Correlation of percentage body mass index change with percentage change in pain, stiffness, activities of daily living (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) after 6 months post-bariatric surgery

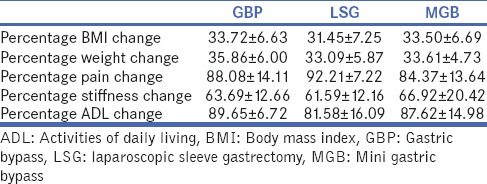

On comparing the types of surgery with respect to 6th-month weight loss, change in BMI and WOMAC score parameters, all the surgeries (LSG, MGB and LGB) gave insignificant results showing that all the surgeries are equally capable of reducing weight and improving BMI [Table 4].

Table 4.

Correlation of type of surgeries with percentage change in weight reduction, body mass index and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index score after 6 months of post-bariatric surgery

None of the patients required total knee transplant during the study period as there was a significant reduction in pain and improvement in daily activity in all patients.

DISCUSSION

Bariatric surgery does seem to improve symptoms of OA. This was felt true in our study for weight-bearing knee joint. Weight reduction was significant, and its impact on knee pain and function was also found to be improved.

Obesity-related OA is multifaceted, can be due to mechanical factor which includes increased joint forces which gradually leads to decreased joint space, muscle strength and altered biomechanics.[16,17] Ageing and metabolic factor are thought to be another factor, in which adipokine levels produce biomechanical environment where chondrocytes do not respond to challenges,[18,19] and ageing produces lipid and humoral mediators which initiate and progresses the disease process.[20]

The main risk factors for the development of OA are mainly advancing age and weight gain. Many studies have found moderate-to-strong correlation between knee OA and obesity. A meta-analysis of 36 papers found a strong correlation between knee OA and obesity.[21] Another review with 22 years of follow-up by Toivanen et al. found a strong correlation where patients with BMI >30 kg/m2 found to have a 7-fold increase risk of developing knee OA confirming that obesity along with other factors is a major risk for the development of OA.[22]

With changing trends for knee pain where conservative methods are only limited to non-obese, surgical management of knee pain in obese osteoarthritis patients i.e., knee replacement outcome was also questionable due to intra- and post-operative reasons such as higher incidence of wound dehiscence, superficial infections, thromboembolic events,[4,20] higher intraoperative blood loss leading to longer operative time, early failure, high revision rates and malposition of implants.[2,23]

Outcome of bariatric surgery before orthopaedic surgery showed a direct result in effective weight loss, which has shown interest by orthopaedic surgeon in managing obesity before performing knee replacement surgery. A study by Parvizi et al. on total joint replacement in twenty patients surgically treated for morbid obesity showed excellent outcome after TKR, with no prosthesis loosening and revision required.[24] The mean reduction in BMI was 29 kg/m2 from 49 kg/m2.[24]

Systemic review on benefits of bariatric surgery in obese patients with hip and knee OA by Gill et al.,[25] where a total of six studies were included for qualitative analysis found a general trend were improved hip and knee OA following marked weight loss secondary to bariatric surgery was seen. Another study by Abu Abeid et al. on 64 patients, of which 59 completed the follow-up found that surgically induced weight loss, is an effective, rapid and dependable means of reversing the radiological signs of early changes associated with OA.[26] TKR and bariatric surgery both have positive effects on knee in reducing knee pain;[2,4] however, bariatric surgery has additional advantage on overall body by managing diabetes, hypertension,[14] dyslipidaemia, cardiovascular disease, etc.[27]

The present study showed a significant positive correlation of percentage loss of BMI with percentage change in pain and activities of daily living. A supportive study by Pascal on 140 patients after bariatric surgery found that with massive weight loss, pain and inflammation was reduced and there was an increase in knee function.[28] Another supportive study showing the effect of weight reduction on eighty knee OA patients found that with 10% weight reduction, function was increased by 28%.[29,30] Six months of follow-up showed patient satisfaction in pain relief and improved ADLs, thus delaying the need for TKR. The structural damage and severity of symptoms caused by Grade IV OA could not reverse the stiffness symptoms significantly numerically within 6 months though the patients’ feedback showed a reduction in stiffness while walking. Maybe future research and follow-up study is needed to find the long-term change of weight reduction on stiffness and need for TKR.

Obese patients with OA, who lose weight showed improvement, due to decrease load on the knee joint and may be due to decrease in inflammatory markers.[31] With weight reduction, there is relative loss of muscle mass and strength over time due to protein deficiency which may contribute lately for recurrence of OA symptoms.[30]

Enhanced dietary intake of protein in combination with specific knee exercise protocols accelerated their activity level, improved physical fitness including muscle strength in the muscles around knee joint making the effects of bariatric surgery long lasting, preventing demineralisation and delay knee replacement procedure. As their maintenance, we encouraged our patients to continue knee exercises further with some modifications to overcome degenerative changes due to ageing in future.

The weight reduction pattern observed was highly significant for 6 months follow-up, irrespective of the type of bariatric surgery performed. Thus, all the three bariatric surgery procedures performed LSG, MGB and LGB were equally effective. Similar to our study, Dicker et al. show that all the surgeries are equally effective in reducing the BMI over a long term.[32]

CONCLUSION

Thus, we conclude that for all obese patients with OA, weight loss may be considered as the first line of management and hence bariatric surgery with dietary and exercise changes is an important tool for both prevention and management of obesity with OA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366:1197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vu L, Switzer NJ, Durand DC, Hedden D, Karmal S. Outcomes of osteoarthritis after bariatric surgery. Surg Curr Res. 2013;3:4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey R, Kumar N, Paroha S, Prasad R, Yadav M, Jain S, et al. Impact of obesity and diabetes on arthritis: An update. Health. 2013;5:143–56. doi: 10.4236/health.2013.51019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards C, Rogers A, Lynch S, Pylawka T, Silvis M, Chinchilli V, et al. The effects of bariatric surgery weight loss on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis. 2012;2012:504189. doi: 10.1155/2012/504189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King LK, March L, Anandacoomarasamy A. Obesity & osteoarthritis. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:185–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD, Morgan TM, Rejeski WJ, Sevick MA, et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: The Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1501–10. doi: 10.1002/art.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma MK, Swami HM, Bhatia V, Verma A, Bhatia SP, Kaur G. An epidemiological study of correlates of osteo-arthritis in geriatric population of UT Chandigarh. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:77–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holliday KL, McWilliams DF, Maciewicz RA, Muir KR, Zhang W, Doherty M. Lifetime body mass index, other anthropometric measures of obesity and risk of knee or hip osteoarthritis in the GOAL case-control study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM, Naimark A, Anderson JJ. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:535–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-7-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piva SR, Moore CG, Schneider M, Gil AB, Almeida GJ, Irrgang JJ. A randomized trial to compare exercise treatment methods for patients after total knee replacement: Protocol paper. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:303. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0761-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Núñez M, Núñez E, del Val JL, Ortega R, Segur JM, Hernández MV, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with osteoarthritis after total knee replacement: Factors influencing outcomes at 36 months of follow-up. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:1001–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CA, Cox V, Jhangri GS, Suarez-Almazor ME. Delineating the impact of obesity and its relationship on recovery after total joint arthroplasties. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:511–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bariatric Surgery Procedures. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 12]. Available from: http://www.asmbs.org/patients/bariatric-surgery-procedures .

- 14.Quan Y, Huang A, Ye M, Xu M, Zhuang B, Zhang P, et al. Efficacy of laparoscopic mini gastric bypass for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:152852. doi: 10.1155/2015/152852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, DeVita P. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2026–32. doi: 10.1002/art.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runhaar J, Koes BW, Clockaerts S, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. A systematic review on changed biomechanics of lower extremities in obese individuals: A possible role in development of osteoarthritis. Obes Rev. 2011;12:1071–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King LK, Birmingham TB, Kean CO, Jones IC, Bryant DM, Giffin JR. Resistance training for medial compartment knee osteoarthritis and malalignment. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1376–84. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31816f1c4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gómez R, Conde J, Scotece M, Gómez-Reino JJ, Lago F, Gualillo O. What's new in our understanding of the role of adipokines in rheumatic diseases? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:528–36. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garnero P, Rousseau JC, Delmas PD. Molecular basis and clinical use of biochemical markers of bone, cartilage, and synovium in joint diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:953–68. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<953::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velasquez MT, Katz JD. Osteoarthritis: Another component of metabolic syndrome? Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:295–305. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, Jordan KP. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toivanen AT, Heliövaara M, Impivaara O, Arokoski JP, Knekt P, Lauren H, et al. Obesity, physically demanding work and traumatic knee injury are major risk factors for knee osteoarthritis – A population-based study with a follow-up of 22 years. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:308–14. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillespie GN, Porteous AJ. Obesity and knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2007;14:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parvizi J, Trousdale RT, Sarr MG. Total joint arthroplasty in patients surgically treated for morbid obesity. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:1003–8. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.9054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill RS, Al-Adra DP, Shi X, Sharma AM, Birch DW, Karmali S. The benefits of bariatric surgery in obese patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12:1083–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abu Abeid S, Wishnitzer N, Szold A, Leibergall M, Manor O. The influence of surgically-induced weight loss on knee joint. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1437–42. doi: 10.1381/096089205774859281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tailleux A, Rouskas K, Pattou F, Staels B. Bariatric surgery, lipoprotein metabolism and cardiovascular risk. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2015;26:317–24. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richette P, Poitou C, Garnero P, Vicaut E, Bouillot JL, Lacorte JM, et al. Benefits of massive weight loss on symptoms, systemic inflammation and cartilage turnover in obese patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:139–44. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christensen R, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Weight loss: The treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bliddal H, Leeds AR, Christensen R. Osteoarthritis, obesity and weight loss: Evidence, hypotheses and horizons – A scoping review. Obes Rev. 2014;15:578–86. doi: 10.1111/obr.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forsythe LK, Wallace JM, Livingstone MB. Obesity and inflammation: The effects of weight loss. Nutr Res Rev. 2008;21:117–33. doi: 10.1017/S0954422408138732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dicker D, Yahalom R, Comaneshter DS, Vinker S. Long-term outcomes of three types of bariatric surgery on obesity and type 2 diabetes control and remission. Obes Surg. 2016;26:1814–20. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-2025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]