Abstract

Background:

One anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass (OAGB) is believed to be more malabsorptive than Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. A number of patients undergoing this procedure suffer from severe protein–calorie malnutrition requiring revisional surgery. The purpose of this study was to find the magnitude of severe protein–calorie malnutrition requiring revisional surgery after OAGB and any potential relationship with biliopancreatic limb (BPL) length.

Methods:

A questionnaire-based survey was carried out on the surgeons performing OAGB. Data were further corroborated with the published scientific literature.

Results:

A total of 118 surgeons from thirty countries reported experience with 47,364 OAGB procedures. Overall, 0.37% (138/36,952) of patients needed revisional surgery for malnutrition. The highest percentage of 0.51% (120/23,277) was recorded with formulae using >200 cm of BPL for some patients, and lowest rate of 0% was seen with 150 cm BPL. These data were corroborated by published scientific literature, which has a record of 50 (0.56%) patients needing surgical revision for severe malnutrition after OAGB.

Conclusions:

A very small number of OAGB patients need surgical correction for severe protein–calorie malnutrition. Highest rates of 0.6% were seen in the hands of surgeons using BPL length of >250 cm for some of their patients, and the lowest rate of 0% was seen with BPL of 150 cm. Future studies are needed to examine the efficacy of a standardised BPL length of 150 cm with OAGB.

Keywords: Biliopancreatic limb, malnutrition, mini-gastric bypass, omega loop gastric bypass, one anastomosis gastric bypass, single anastomosis gastric bypass

INTRODUCTION

Notwithstanding its controversial aspects,[1] one anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass (OAGB) is rapidly gaining in popularity in many parts of the world with several thousand cases now published in the scientific literature.[2] It is a variant of gastric bypass which involves the construction of a long lesser curvature-based gastric pouch followed by a gastroenterostomy approximately 150–200 cm distal to the duodenojejunal flexure.[2] Although not reported in small studies,[3] clinically significant protein–calorie malnutrition needing revisional surgery has been reported[2] with this procedure and appears to be more common than seen with the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB).[4] The reported incidence is as high as 1.28% in some studies.[5]

Experience with RYGB has shown that a range of 100–200 cm for combined length of biliopancreatic limp (BPL) and alimentary limb gives optimum results in most patients. Distal RYGB with longer alimentary limb or BPL carries higher risks of malnutrition, without corresponding significant gains in weight and comorbidity resolution outcomes.[6] Even though many authors have reported using 200 cm BPL length as the standard length of BPL with OAGB,[3,7,8,9] there is currently no consensus on the optimum length of BPL with OAGB and the reported lengths vary from 150 cm on the shorter side[10] to variable length formulae using significantly longer limbs for heavier patients.[11] It is currently unclear if there is a link between the severe protein–calorie malnutrition with OAGB and the length of the BPL. In the absence of such data, it has proved difficult to standardise the length of the BPL with this operation.

The purpose of this study was to find the magnitude of severe protein–calorie malnutrition requiring further revisional surgery with OAGB. This outcome was chosen for two reasons. First, it would take into account a number of clinical problems such as severe malabsorption with persistent diarrhoea, severe hypoalbuminaemia and excessive weight loss that are often bundled together as severe protein–calorie malnutrition. The second reason was that this is a specific measurable outcome that has been widely reported in the literature on this topic. We also examine any potential relationship between this complication and the length of the BPL used in operation.

METHODS

Since it appears to be a low magnitude problem with each surgeon reporting only a few cases, we decided to conduct a worldwide survey of OAGB surgeons to understand the full scale of the problem. Surgeons performing this operation were identified through published scientific articles, e-mail chat group of OAGB surgeons, personal communication, use of social media and by e-mailing presidents of all the national bariatric societies affiliated to the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders. These surgeons were then invited by e-mail to participate in a questionnaire-based survey on SurveyMonkey® starting on 1st January 2016. The link to the survey was also freely shared on various e-mail groups, electronic platforms of bariatric surgeons and social media. The survey was closed for analysis on 15th April 2016. We captured data on the nationality of the surgeon, cumulative experience of the surgeon with this operation, contraindications to this procedure in their practice, length of the BPL, magnitude of severe protein–calorie malnutrition requiring revisional surgery and nature of any revisional surgery performed. Further clarification was obtained by writing to the surgeons individually as and when needed. Basic descriptive statistics was used.

For the purposes of this study, the severe nutritional complication was defined as excessive weight loss or protein–calorie malnutrition severe enough to justify revisional surgery. This end-point was chosen over less severe nutritional complications to minimise recall bias and also because it is a widely reported outcome measure in the published literature on this procedure. However, this problem can never be completely overcome with any survey. We hence further corroborated the survey data with published rates of revisional surgery for severe protein–calorie malnutrition with OAGB in the English language scientific literature. Previously published reviews[1,2,12] have not examined this issue in any depth. For this part of the study, we carried out a search of PubMed using various combinations of keywords ‘bariatric surgery’ or ‘obesity surgery’ or ‘gastric bypass’ or ‘mini gastric bypass’ or ‘omega loop bypass’ or ‘single anastomosis gastric bypass’ or ‘one anastomosis gastric bypass’ to identify all the studies on OAGB. No time filter was used. The last of these searches was carried out on 20th January 2016. Relevant articles were also identified from the references of these articles. All English language articles on OAGB that described any original experience with this procedure were then retrieved and reviewed.

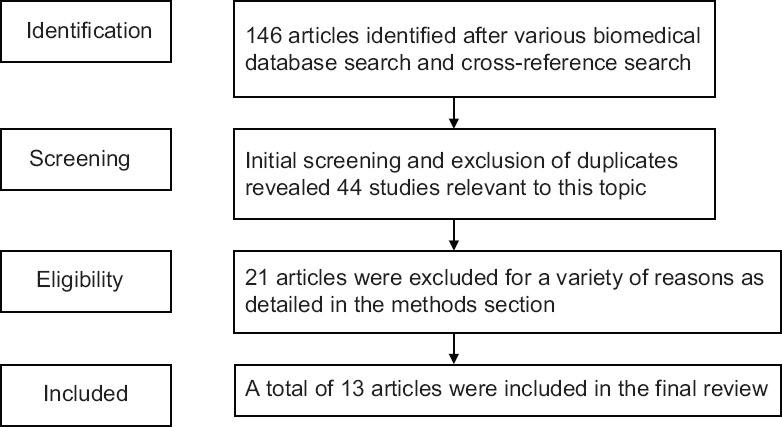

We excluded multiple studies from the same centre to avoid potential duplication of data and studies that did not report on the malnutrition with this procedure.[13] Studies on patients with body mass index (BMI) <35 were also excluded[14,15,16,17,18] as were the reviews without any original data.[1,2,12] Studies that focussed on the metabolic aspect of operation and did not report on nutritional and other complications were excluded[19] too. Finally, a total of 13 studies were included for this part of the study. Figure 1 provides a PRISMA flowchart for article selection. No Institutional Review Board approval was needed for this survey and systematic review of the literature.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for article selection

RESULTS

Country of origin and experience

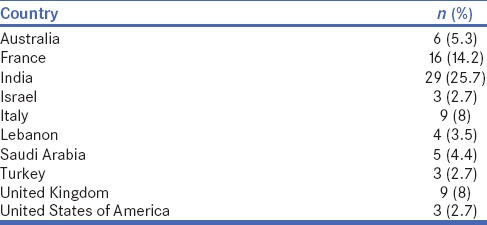

A total of 118 surgeons from thirty countries reported having performed 47,364 (range 1–6000) OAGB procedures between September 1997 and April 2016. Table 1 lists countries with three or more respondents. With 25.7% (n = 29) of surgeons, India accounted for the largest number of the respondents followed by France with 14.2% (n = 16) of respondents. With 8% (n = 9) of respondents each, Italy and the United Kingdom were both at the third place. Out of these surgeons, 46.85% (52/111) of surgeons reported having performed over 100 procedures each, 18.92% (21/111) had performed between 51 and 100 procedures and 34.23% (38/111) had performed between 1 and 50 procedures at the time of filling this survey.

Table 1.

Country of origin of one anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass surgeons

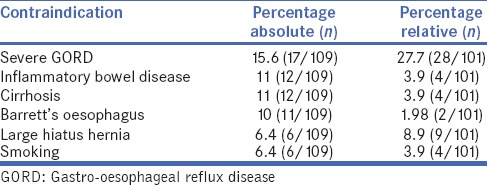

Contraindications to one anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass

Fifty-five per cent (60/109) of the respondents reported using at least one absolute contraindication to this procedure in their practice, and 74% of the respondents (75/101) reported at least one relative contraindication. Table 2 lists commonly reported absolute and relative contraindications.

Table 2.

Commonly reported contraindications for one anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass surgeons

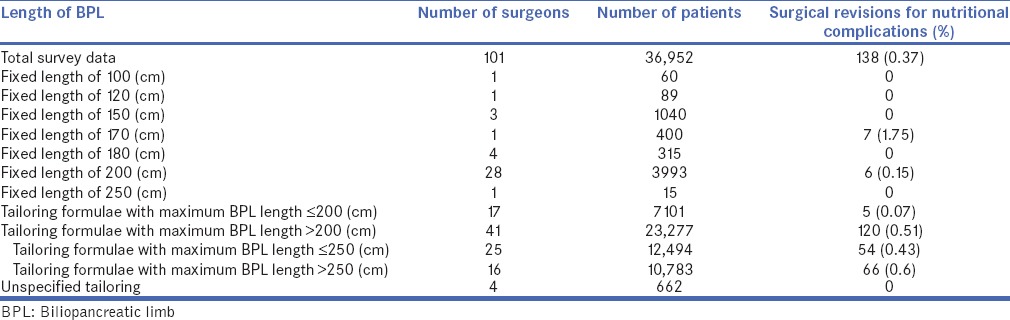

Severe malnutrition needing revisional surgery and its relationship with biliopancreatic limb

A total of 101 surgeons provided data on severe protein–calorie malnutrition needing further revisional surgery in 36,952 patients. Some respondents did not provide information on this complication accounting for the discrepancy with total numbers as above. Out of this, 38.6% (39/101) of surgeons used a fixed BPL length ranging from 100 to 250 cm. The most common fixed limb length was 200 cm, which was used by 27.7% (28/101) of surgeons. A number of other fixed limb lengths were also used as detailed in Table 3. Sixty-two (61.4%) surgeons reported using 44 different variable length formulae depending on a number of patient characteristics such as age, BMI, sex, eating behaviour (shorter limbs for vegetarians), presence or absence of diabetes, nature of surgery (primary or revisional) and total small bowel length.

Table 3.

Relationship between biliopancreatic limb length and severe protein–calorie malnutrition requiring revisional surgery

Table 3 provides a list of severe protein–calorie malnutrition needing further revisional surgery for different lengths of BPL. The overall complication rate was 0.37% (138/36,952). The highest percentage of 0.51% (120/23,277) was recorded with variable length formulae using >200 cm of BPL for some patients. The most common fixed BPL length of 200 cm was associated with 0.15% (6/3993) complication rate. Variable length formulae using ≤200 cm BPL were associated with an even lower complication rate of 0.07% (5/7101). This trend continued with 0% complication rates seen in 315 patients with 180 cm BPL (used by four surgeons) and 1040 patients with 150 cm BPL (used by three surgeons). Somewhat higher than expected number of 1.75% (7/400) was only reported by one surgeon.

For surgeons who reported revisions with variable length formulae, further information on the length of BPL was sought by e-mailing them. This information was provided by 12 surgeons on 30 patients, and all of these patients had BPL length of >200 cm. The reported range varied from 230 to 300 cm.

Out of 138 patients, who needed further surgery for severe protein–calorie malnutrition, 71 (51.44%) patients underwent reversal of OAGB, 60 (43.4%) underwent sleeve gastrectomy, 2 (1.45%) underwent RYGB and 5 (3.6%) underwent shortening of the BPL.

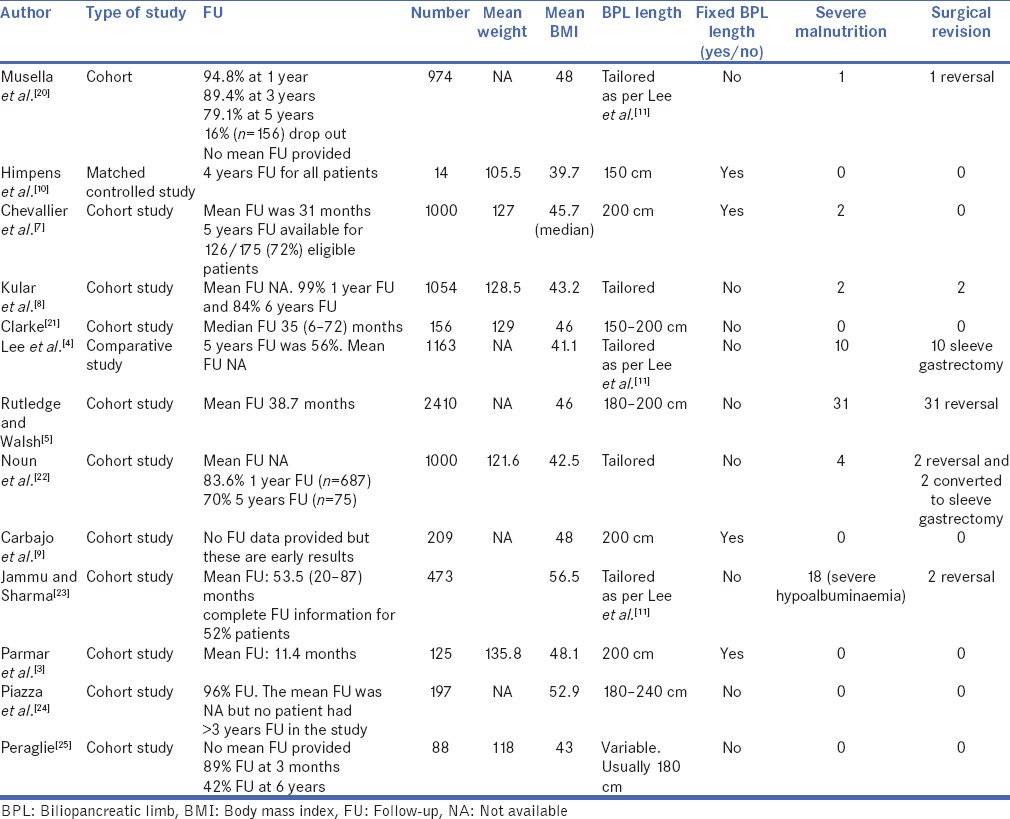

Data from published studies on one anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass

Table 4[3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,20,21,22,23,24,25] gives an overview of published OAGB data, especially with special reference to the length of BPL and severe protein–calorie malnutrition. A total of 13 studies reported on 8863 patients with a mean age of 38.17 years and a mean weight and BMI of 126 kg and 45.5 kg/m2, respectively. Out of these, 6411 (72.3%) were female. Four (31%) of these studies used a fixed length of BPL in their patients (one study used 150 cm and three studies used 200 cm). Remaining 9 (69%) studies used a variable length formula for BPL depending on the BMI of the patient. The reported frequency of severe protein–calorie malnutrition ranged from 0%[8] to 1.1%.[4] A total of 68 (0.76%) patients presented with severe protein–calorie malnutrition and 50 of these (0.56%) needed surgical correction. Out of these fifty patients, 38 underwent reversal (76%) of the OAGB and the remaining 12 were converted to SG (24%).

Table 4.

Basic demographics, limb length and severe protein–calorie malnutrition requiring revisional surgery in published one anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass studies

DISCUSSION

Severe protein–calorie malnutrition needing surgical revision is one of the recognised problems with OAGB.[2] The frequency of 0.37% that we found in our survey and 0.56% in published literature does prove that severe protein–calorie malnutrition needing further revisional surgery is relatively rare after OAGB. The highest rate of 0.6% was seen in the survey with variable length formulae using BPL in excess of 250 cm for some patients, and lowest rates of 0% were seen with BPL of 150 cm or lower.

As it is evident from both the survey and the review part of this paper, a BPL length of at least 200 cm is the one used most frequently. In our survey, it was associated with 0.15% chance of severe nutritional issues needing corrective surgery. The fact that one of the survey surgeons observed a 1.75% rate for this complication with 170 cm and other surgeons have reported 1.28% rate with 180–200 cm[5] can be explained by variations in patient characteristics or a lack of precision in techniques used for measurement of small bowel length.[26]

A recent systematic review suggested that most of the benefits of RYGB could be obtained with a combined alimentary and BPL length range of 100–200 cm.[6] It was suggested that an ideal combined alimentary and BPL limb length of 150 cm would be able to absorb most of the errors in measurement and keep surgeons in the suggested ideal range of 100–200 cm.[6] It could be reasonably extrapolated that similar to the Standard Proximal RYGB.[6] Most of the benefits of the OAGB could also be obtained with a BPL length of 150 cm. As we have found in this paper, it will reduce the rates of severe protein–calorie complications needing revisional surgery down to zero. The safety and efficacy of 150 cm BPL with OAGB does, however, merit further scientific confirmation.

Just like there is no consensus on the limb lengths with RYGB,[27] this study shows that there is wide variation in the length of BPL with OAGB. In fact, a majority of surgeons are now using one of a large number of variable length formulae to determine the length of the BPL. We found that 61.4% of survey respondents and 69% of published authors did not use a fixed BPL length while performing OAGB.

There is little doubt that a definite percentage of patients who have undergone OAGB suffer from severe protein–calorie malnutrition and need further corrective surgery. In this study, we found a 0.37% revisional surgery rate for such complications in the survey of OAGB surgeons and 0.56% in the published studies. Since the difference between two numbers is not much, any potential for underreporting in the survey must be small.

This study has several unique features. It is the first global survey of surgeons performing OAGB. No other study in the scientific literature to date has attempted to understand variations in the length of BPL used with this procedure. This is also the first attempt at quantifying severe protein–calorie malnutrition requiring corrective surgery after OAGB. It is also the first paper to explore any link between severe protein–calorie malnutrition after OAGB and longer lengths of BPL. Our finding that BPL length of 150 cm was able to reduce nutritional complications down to 0% could help standardise the BPL length with OAGB. Future-focussed studies need to examine whether it would be associated with any reduction in the efficacy of this operation.

There are several weaknesses to this paper. There is a significant potential for underestimation of this problem in our survey due to recall bias and loss to follow-up. This study focuses on severe protein–calorie malnutrition and does not examine micronutrient deficiency and compliance with supplements. These issues need to be examined in future studies. Moreover, this study can only report on early revisions for protein–calorie malnutrition as there is a real lack of long-term data on this procedure. It cannot hence be ruled out that more patients might present with this problem in due course though authors expect that number to be small.

Moreover, we cannot guarantee that we have managed to capture every single surgeon performing OAGB, and since the survey was widely advertised among the bariatric surgical community, we do not know the response rate. However, this is unlikely to seriously compromise the importance of this investigation as we know from our personal experience with this community that this survey has captured most of the influential voices on this procedure as well as most surgeons with significant experience. It is still possible that surgeons with higher complication rate than what has been reported have not participated in the survey leading to a further potential for underestimation. This survey will also miss those patients who have been operated for by surgeons other than the primary surgeons. However, these weaknesses should at least partly be overcome by our examination of published data and might perhaps also explain the observed slight difference between the rates seen with the survey and that within the published literature.

The reported revision rates may further vary depending on the threshold of an individual surgeon and other patient or surgeon characteristics independent of the length of the BPL. Finally, since this investigation focuses on the most severe forms of protein–calorie malnutrition, it cannot tell us about less severe forms of protein–calorie malnutrition that presumably affect a larger patient population with consequent impairment of gastrointestinal quality of life.

The quality of any survey data is recognised to be weak as it suffers from not only recall bias but also potential for deliberate underreporting. It was precisely for this reason that we corroborated our survey data with that from the published literature. However, those data in itself suffer from publication bias and surveys of this nature remain in the opinion of the authors the best tool for preliminary exploration of a relatively rare problem.

CONCLUSIONS

Approximately, 0.37%–0.56% of patients undergoing OAGB need surgical correction for severe nutritional issues. Highest rates of 0.6% for this complication were seen in the hands of surgeons using variable length recommending BPL length of >250 cm and lowest rates of 0% in the hands of surgeons using a BPL of 150 cm or lower. Future studies need to examine the efficacy of a standardised BPL length of 150 cm with OAGB.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahawar KK, Carr WR, Balupuri S, Small PK. Controversy surrounding ‘mini’ gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2014;24:324–33. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahawar KK, Jennings N, Brown J, Gupta A, Balupuri S, Small PK. “Mini” gastric bypass: Systematic review of a controversial procedure. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1890–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parmar CD, Mahawar KK, Boyle M, Carr WR, Jennings N, Schroeder N, et al. Mini gastric bypass:First report of 125 consecutive cases from United Kingdom. Clin Obes. 2016;6:61–7. doi: 10.1111/cob.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee WJ, Ser KH, Lee YC, Tsou JJ, Chen SC, Chen JC. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y vs.mini-gastric bypass for the treatment of morbid obesity: A 10-year experience. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1827–34. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0726-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutledge R, Walsh TR. Continued excellent results with the mini-gastric bypass: Six-year study in 2,410 patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1304–8. doi: 10.1381/096089205774512663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahawar KK, Kumar P, Parmar C, Graham Y, Carr WR, Jennings N, et al. Small bowel limb lengths and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A systematic review. Obes Surg. 2016;26:660–71. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chevallier JM, Arman GA, Guenzi M, Rau C, Bruzzi M, Beaupel N, et al. One thousand single anastomosis (omega loop) gastric bypasses to treat morbid obesity in a 7-year period: Outcomes show few complications and good efficacy. Obes Surg. 2015;25:951–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1552-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kular KS, Manchanda N, Rutledge R. A 6-year experience with 1,054 mini-gastric bypasses-first study from Indian subcontinent. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1430–5. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbajo M, García-Caballero M, Toledano M, Osorio D, García-Lanza C, Carmona JA. One-anastomosis gastric bypass by laparoscopy: Results of the first 209 patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:398–404. doi: 10.1381/0960892053576677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Himpens JM, Vilallonga R, Cadière GB, Leman G. Metabolic consequences of the incorporation of a Roux limb in an omega loop (mini) gastric bypass: Evaluation by a glucose tolerance test at mid-term follow-up. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2935–45. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4581-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee WJ, Wang W, Lee YC, Huang MT, Ser KH, Chen JC. Laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass: Experience with tailored bypass limb according to body weight. Obes Surg. 2008;18:294–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan Y, Huang A, Ye M, Xu M, Zhuang B, Zhang P, et al. Efficacy of laparoscopic mini gastric bypass for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:152852. doi: 10.1155/2015/152852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tolone S, Cristiano S, Savarino E, Lucido FS, Fico DI, Docimo L. Effects of omega-loop bypass on esophagogastric junction function. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garciacaballero M, Martínez-Moreno JM, Toval JA, Miralles F, Mínguez A, Osorio D, et al. Improvement of C peptide zero BMI 24-34 diabetic patients after tailored one anastomosis gastric bypass (BAGUA) Nutr Hosp. 2013;28(Suppl 2):35–46. doi: 10.3305/nh.2013.28.sup2.6712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Caballero M, Valle M, Martínez-Moreno JM, Miralles F, Toval JA, Mata JM, et al. Resolution of diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in normal weight 24-29 BMI patients with One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27:623–31. doi: 10.1590/S0212-16112012000200041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garciacaballero M, Reyes-Ortiz A, García M, Martínez-Moreno JM, Toval JA, García A, et al. Changes of body composition in patients with BMI 23-50 after tailored one anastomosis gastric bypass (BAGUA): Influence of diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Obes Surg. 2014;24:2040–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee WJ, Almulaifi A, Chong K, Chen SC, Tsou JJ, Ser KH, et al. The effect and predictive score of gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy on type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with BMI < 30 kg/m(2) Obes Surg. 2015;25:1772–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Z, Hur KY. Laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass for type 2 diabetes: The preliminary report. World J Surg. 2011;35:631–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0909-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carbajo MA, Jiménez JM, Castro MJ, Ortiz-Solórzano J, Arango A. Outcomes in weight loss, fasting blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin in a sample of 415 obese patients, included in the database of the European accreditation council for excellence centers for bariatric surgery with laparoscopic one anastomosis gastric bypass. Nutr Hosp. 2014;30:1032–8. doi: 10.3305/nh.2014.30.5.7720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Musella M, Susa A, Greco F, De Luca M, Manno E, Di Stefano C, et al. The laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass: The Italian experience: Outcomes from 974 consecutive cases in a multicenter review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:156–63. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3141-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke MG, Wong K, Pearless L, Booth M. Laparoscopic silastic ring mini-gastric bypass: A single centre experience. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1852–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noun R, Skaff J, Riachi E, Daher R, Antoun NA, Nasr M. One thousand consecutive mini-gastric bypass: Short-and long-term outcome. Obes Surg. 2012;22:697–703. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jammu GS, Sharma R. A 7-year clinical audit of 1107 cases comparing sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and mini-gastric bypass, to determine an effective and safe bariatric and metabolic procedure. Obes Surg. 2016;26:926–32. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1869-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piazza L, Ferrara F, Leanza S, Coco D, Sarvà S, Bellia A, et al. Laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass: Short-term single-institute experience. Updates Surg. 2011;63:239–42. doi: 10.1007/s13304-011-0119-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peraglie C. Laparoscopic mini-gastric bypass in patients age 60 and older. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:38–43. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isreb S, Hildreth AJ, Mahawar K, Balupuri S, Small PK. Laparoscopic instruments marking improve length measurement precision. World J Laparosc Surg. 2009;2:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welbourn R, Small P, Finlay I, Sarela A, Somers S, Mahawar K. Second National Bariatric Surgery Report. [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 22]. Available from: http://www.bomss.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Extract_from_the_NBSR_2014_Report.pdf .