Abstract

Objective

Assess perceptions of prevalence, safety, and screening practices for cigarettes and secondhand smoke exposure (SHSe), marijuana (and synthetic marijuana), electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS; e.g., e-cigarettes), nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and smoking-cessation medications during pregnancy, among primary care physicians (PCPs) providing obstetrical care.

Methods

A web-based, cross-sectional survey was e-mailed to 3750 US physicians (belonging to organizations within the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance). Several research groups’ questions were included in the survey. Only physicians who reported providing “labor and delivery” obstetrical care responded to questions related to the study objectives.

Results

A total of 1248 physicians (of 3750) responded (33.3%) and 417 reported providing labor and delivery obstetrical care. Obstetrical providers (N=417) reported cigarette (54%), marijuana (49%), and ENDS use (24%) by “Some (6–25%)” pregnant women, with 37% endorsing that “Very Few (1–5%)” pregnant women used ENDS. Providers most often selected that very few pregnant women used NRT (45%), cessation medications (i.e., bupropion or varenicline; 37%), and synthetic marijuana (23%). Significant proportions chose “Don’t Know” for synthetic marijuana (58%) and ENDS (27%). Over 90% of the sample perceived that use of or exposure to cigarettes (99%), synthetic marijuana (99%), SHS (97%), marijuana (92%), or ENDS (91%) were unsafe, with the exception of NRT (44%). Providers most consistently screened for cigarette (85%) and marijuana use (63%), followed by SHSe in the home (48%), and ENDS (33%) and synthetic marijuana use (28%). Fewer than a quarter (18%) screened consistently for all substances and SHSe. A third (32%) reported laboratory testing for marijuana and 3% reported laboratory testing for smoking status.

Conclusion

This sample of PCPs providing obstetrical care within academic settings perceived cigarettes, marijuana, and ENDS use to be prevalent and unsafe during pregnancy. Opportunities for increased screening during pregnancy across these substances were apparent.

Cover/Footer: Screening for cigarettes, marijuana, electronic-nicotine during pregnancy

Keywords: Electronic Cigarettes, Family Physicians, Marijuana, Maternal Health, Obstetrics, Pregnancy, Primary Health Care, Screening, Tobacco Products

1. Introduction

Understanding the role of physicians in mitigating the use of various substances during pregnancy is complex. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) provides guidelines to screen for and recommend cessation of tobacco (including elimination of secondhand smoke exposure [SHSe]) and marijuana use during pregnancy.1–3 These ACOG guidelines were first published in 2002 (revised in 2010), with marijuana added as a committee opinion in 2015. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) echo recommendations on cessation of tobacco use during pregnancy (Grade A recommendation).4,5 While the USPSTF concluded that current evidence is insufficient (Grade I) for screening pregnant women for marijuana use and other illicit drugs,6 others advocate for screening and appropriate referrals in the primary care setting, depending on severity of use.7 No guidelines exist to screen for electronic-nicotine delivery systems’ (ENDS; e.g., e-cigarettes) use during pregnancy but the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends cautioning pregnant women against use.8 These existing guidelines and recommendations make it important to explore how often primary care providers (PCPs) with an obstetrical practice may screen for cigarettes and SHSe, marijuana (and synthetic marijuana), and ENDS use during pregnancy. Providers’ perceptions of the prevalence and safety of use during pregnancy are likely related to screening behavior and thus important to investigate.

Cigarettes, marijuana, and ENDS use fit broadly under an umbrella of substances that are inhalable and known or suspected to cause health risks to developing fetuses. Further, both marijuana and ENDS may be perceived by patients as safe as or less harmful than other substances (e.g., cigarettes) and are increasingly available (i.e., due to decriminalization/legalization of marijuana), but physicians’ perceptions of relative safety for use during pregnancy remain under researched. Surveying PCPs who teach in academic settings and provide obstetrical care may provide an important window into current perceptions of prevalence, safety/harm, and screening practices for these substances. This group is directly responsible for overseeing trainees’ obstetrical practices, and therefore their attitudes and behaviors have the potential for significant influence.

Health risks of smoking tobacco9 and SHSe10 during pregnancy are well documented, and recent large-scale smoking bans in public places are associated with improved pregnancy outcomes (e.g., reduced preterm delivery).11,12 It remains unclear, however, how often providers ask pregnant patients about smoking, SHSe, or use a gold-standard metric (e.g., urine testing for nicotine’s metabolite, cotinine), which identifies more pregnant women who smoke than self-report alone.13 SHSe remains a significant public health burden10, 14–16 and a recent study found that fewer than half of pregnant women being seen in an urban, university-based prenatal clinic (43%) reported living in a home that completely bans smoking in the home and car(s),13 underscoring needs for consistent screening and effective intervention.

Marijuana has recently been decriminalized or legalized in several states, potentially increasing public perception that it has few untoward effects, and it is the most commonly used illicit drug,17 with recent increases in prevalence18,19 (especially with younger adults).19 Self-reported rates in the past 30 days approached 4% in pregnant women,20 with some samples (employing urine toxicology) suggesting use as high as 29.6% at the initial prenatal visit.21 Large, well-controlled studies report significantly increased birth and neonatal risks of marijuana use during pregnancy, including stillbirth (based on data from 663 stillbirth deliveries and 1932 live birth deliveries)22 and low birth weight (LBW), preterm labor, small for gestational age, and admission to a NICU (in a sample of 24,874 women who delivered between 2000 and 2006 in Australia).23 Another large study (N=12,000) reported that women using marijuana weekly or more often had babies born 90g lighter than non-users.24 Cannabimimetics and other synthetic compounds (e.g., “K2”, “Spice”; sometimes marketed as synthetic marijuana) pose potential health risks if used during pregnancy. While human studies on synthetic drug prevalence among pregnant women and the effects on fetal development are lacking, animal studies have demonstrated the significant potential for neurodevelopmental harm as early as day 16 during human gestation.25 These data suggest a need for physician education and counseling with pregnant women about potential risks from smoking marijuana (organic or synthetic), but may not fully align with providers’ perceptions about safety/risks. A survey of family physicians in Colorado (N=520) found that most (>60%) but not all reported that marijuana posed serious physical or mental health risks but this survey did not specifically assess perceptions of risks during pregnancy,26 making this an open area of investigation.

ENDS (e.g., e-cigarettes) operate by heating a liquid-nicotine solution, allowing users to inhale (“vape”) the aerosolized solution. These devices have proliferated over the past decade with recent rises in prevalence.27,28 Long-term health risks and risks to developing fetuses are largely unknown and poorly characterized, but the WHO recommends cautioning pregnant women about ENDS use,8 due to preliminary concerns of neurogenic fetal harm.29–31 The lack of research on repetitive inhalation of propylene glycol and other additives/contaminants (present in ENDS vapor) is concerning as well.29 The early state of ENDS research has not deterred public perception of ENDS having a similar/lower-risk profile than cigarettes, as documented in ENDS users,32 the general US population,33 pregnant women,34,35 and physicians.36 Physicians, providing care to pregnant women are in a difficult position when patients express interest in using these devices, particularly as smoking cessation aids. Two studies in non-pregnant patients suggest that 30–35% of physicians recommend e-cigarettes to their patients as a cessation tool36, 37 and 67% of physicians felt e-cigarettes were a helpful cessation aid.36 It is noteworthy that Level I evidence suggests ENDS are not efficacious smoking cessation tools in reproductive-aged women;38,39 and, a recent Cochrane review reported that ENDS as a smoking cessation aid during pregnancy has not been evaluated.40

The recent Cochrane review also evaluated more widely studied smoking cessation aids and concluded there is borderline evidence that nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (combined with counseling) may help stop smoking in later pregnancy.40 However, NRT was no more effective than placebo in well-controlled studies, and insufficient evidence was available to evaluate positive and negative impacts on birth- and infant-related health outcomes (e.g., miscarriage and LBW). Some forms of NRT (i.e., transdermal patches, inhalers, and spray nicotine products; previously labeled Category D41) have associated risks of fetal harm during pregnancy.42 Also, insufficient studies exist to evaluate the safety of bupropion and varenicline during pregnancy and no clinical guidelines recommend them in pregnancy.40 Physicians are likely to weigh the risks of continued smoking during pregnancy against the risks of ENDS, NRT, and smoking-cessation medications, but the literature lacks reports on physicians’ safety perceptions and prescription practices for ENDS, NRT, and smoking-cessation medication use during pregnancy.

Obstetrical care providers are well positioned to screen for cigarette use, SHSe, and marijuana, synthetic marijuana (e.g., “Spice”), and ENDS use during pregnancy, which is a critical first step before referrals or interventions targeting cessation can occur. Evidence supports that smoking cessation interventions during pregnancy can be effective (e.g., NRT increases cessation by 40% in late pregnancy) but more work is needed for larger effects.40,43 Further, evidence-based interventions with non-pregnant populations for SHSe44 and marijuana45 have not been tested with pregnant patients, and a recent Cochrane review concluded that across 14 studies of psychosocial interventions for drug use with pregnant women, there was no difference in treatment outcomes.46 It is clear that efficacious interventions to reduce use and exposure to the substances discussed herein are sorely needed but many physicians may feel compelled to screen for and make recommendations to avoid cigarettes, SHSe, marijuana and synthetic marijuana, and ENDS, rather than wait for well-supported empirical treatments for these substances. For example, the 5 A’s (ask, advise, assess [readiness], assist, and arrange [follow-up]) for smoking cessation.47

The overarching objective of this investigation was to assess and describe perceptions of prevalence and safety/risk and current screening practices related to cigarettes, SHSe, marijuana and synthetic marijuana, ENDS, NRT, and smoking-cessation medications during pregnancy, among PCPs providing obstetrical care, within academic settings. We hypothesized that obstetrical care providers would perceive these exposures as unsafe but screening would not be universal. These data may facilitate recommendations for improved care to pregnant patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Ethical Review

The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at UTHealth and the IRB at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) approved a pilot survey and methodology. The final design was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians IRB (16–255). Participants gave informed consent.

2.2 Participants and Procedures

A web-based survey (www.surveymonkey.com) was e-mailed to a convenience pilot sample of obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) residents, faculty, and midwives at UTHealth, BCM, and the University of Texas Medical Branch. Forty-nine responded (15.8% response rate of 311).

A web-based survey (www.surveymonkey.com) was subsequently e-mailed to 3750 US physicians, utilizing the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA), General Membership Survey, as determined by membership in the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, Association of Departments of Family Medicine, North American Primary Care Research Group, and Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (http://www.stfm.org/Research/CERA). Background on and details from other CERA surveys are published elsewhere.48,49 Four e-mail reminders were sent. Some e-mails were undeliverable (n=80) and some providers opted out (n=68).

The survey (open from February 2nd to March 20th, 2016) contained 56 questions spanning five separate research proposals. As our focus was on obstetrical practice, we only included physicians who responded affirmatively to, “Do you currently provide labor and delivery maternity care within the United States?” (see Appendix). Skip logic prevented survey participants who did not provide labor and delivery care from answering our group’s survey contributions, reducing burden for participants with less-frequent or no contact with pregnant patients.

2.3 Survey Instrument

We surveyed the literature, developed and piloted survey items locally, and solicited feedback from OB/GYN and PCP colleagues to develop, adapt, and refine our question set for parsimony and coherence. Our final question set (see Appendix) was reduced to accommodate multiple assessment domains in the CERA survey, as topic areas are generally limited to 10 questions48 and underwent additional piloting by CERA leadership.49 Question 1 assessed the inclusion criterion and question 2 was included to characterize the number of patients under the age of 18 seen in a practice.

Question 3 asked providers to estimate the prevalence of use for each substance during pregnancy (from their own clinic). Response options for prevalence questions were developed/refined to correspond closely to available data during pregnancy. “Very few (1–5%)” was selected for synthetic marijuana and smoking-cessation medication use, estimated to be infrequent events by our team (published data are lacking). “Some (6–25%)” was chosen to correspond with the reported prevalence range for smoking 3 months before pregnancy (23.0%) and last 3 months of pregnancy (12.8%),50 and marijuana use during pregnancy 4–30%.20, 21 “Many (26–50%)” was provided to accommodate physicians working with populations using substances to a greater degree. “None (0%)” and “Most (>50%)” completed the response range.

For question 4, respondents indicated how safe it is for pregnant women to use each substance, be exposed to secondhand smoke, or breastfeed while smoking (after delivery) using a 5-point scale (“Very Safe, Safe, Somewhat Safe, Unsafe,” or “Very Unsafe”).

Providers indicated how often they screen pregnant patients (question 5) on a 6-point scale (“Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Very Often” or “Always”). Further, we asked about several methods for tobacco/nicotine and marijuana screening (i.e., patient report and laboratory testing) in question 6. Question 7 surveyed ENDS, NRT, and smoking cessation prescription practices.

We adapted two questions about ENDS safety reported in peer-reviewed publications.36 Specifically, to assess whether providers perceived e-cigarettes to have a lower cancer risk than traditional cigarettes, we added “About the same” as a response option, along with “Yes” and “No” (question 8). Question 9 assessed how often providers were asked by patients about the safety of e-cigarette use or their efficacy as a smoking cessation aid (content was adapted to assess “pregnant patients” and “all other patients” separately). Question 10 queried whether providers would advise patients not to use marijuana (if it is or becomes legal in their state).

2.4 Statistical Analyses

The primary data analytic aims were to describe the areas surveyed via frequency counts. The response rate was conservatively estimated as the quotient of all responders (partial and complete) divided by all intended recipients (N=3750).51 Categorical data were compared using chi-squared tests for equal proportions and all comparisons were evaluated at the 0.05 significance level (in SAS 9.4; Cary, NC). We collapsed some directly adjacent response options due to low endorsement (i.e., <5 responses/category; see relevant Table notes).

3. Results

3.1 Response Rate and Characteristics of Family Physicians Providing Obstetrical Care

The response rate was 33.3% (N=1248) of the 3750 intended survey recipients, inclusive of providers with and without a current obstetrical practice. A majority (90.6%; n=1131 out of 1248) responded to the eligibility question and 417 (36.9%; out of 1131) reported providing labor and delivery obstetrical care. Obstetrical care providers tended to be female (56.0%) and White, non-Hispanic (80.3%). Table 1 contains other provider characteristics and demonstrates numerous statistically significant differences in characteristics across providers with and without a current obstetrical practice (e.g., a greater proportion of the sample with a current obstetrical practice tended to be female compared to non-obstetrical providers; 56.0% vs. 46.6%, p<0.01). The final sample size for subsequent data comprised of the 417 family medicine physicians who reported providing labor and delivery maternity care.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Obstetrical Care and Non-Obstetrical Care Provider Status (N=1131)

| Respondent Characteristic | Obstetrical Care PCPs No. (%) | Non-Obstetrical Care PCPs No. (%) | Chi-Squared (χ2), p | |

| N | 417 (100) | 714 (100) | ||

| Female % (n) | 233 (56.0) | 330 (46.6) | χ2=9.3, p<0.01 | |

| Age (Years)* | χ2=49.0, p<0.0001 | |||

| <40 | 129 (31.0) | 140 (19.7) | ||

| 40–49 | 153 (36.8) | 195 (27.5) | ||

| 50–59 | 87 (20.9) | 208 (29.3) | ||

| 60+ | 47 (11.3) | 167 (23.5) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | χ2=11.2, p=0.02 | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 334 (80.3) | 591 (83.6) | ||

| Asian | 21 (5.1) | 50 (7.1) | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17 (4.1) | 26 (3.7) | ||

| Hispanic | 24 (5.8) | 25 (3.5) | ||

| Other | 20 (4.8) | 15 (2.1) | ||

| Rank† | χ2=32.2, p<0.0001 | |||

| Visiting professor or N/A | 60 (5.4) | 62 (5.6) | ||

| Assistant professor | 180 (44.0) | 254 (35.9) | ||

| Associate professor | 118 (28.9) | 216 (30.6) | ||

| Full professor | 51 (12.5) | 175 (24.8) | ||

| Terminal Degree‡ | χ2=6.2, p=0.01 | |||

| MD | 390 (94.0) | 640 (89.6) | ||

| DO or other | 25 (6.0) | 74 (10.4) | ||

| Half-Days of Seeing Patients | χ2=4.2, p=0.12 | |||

| <3 half-days | 190 (45.9) | 361 (51.1) | ||

| 3–6 half-days | 205 (49.5) | 306 (43.3) | ||

| 7+ half-days | 19 (4.6) | 40 (3.6) | ||

| Primary Role§ | χ2=55.3, p<0.0001 | |||

| Clinical teaching | 268 (64.9) | 326 (46.2) | ||

| Administration | 75 (18.2) | 226 (20.2) | ||

| Clinical care | 42 (10.2) | 76 (10.8) | ||

| Research | 5 (1.2) | 43 (6.1) | ||

| Faculty development | 9 (2.2) | 5 (0.7) | ||

| Non-academic physician/other | 14 (3.4) | 30 (4.3) | ||

| Actively teach students/residents | 414 (99.5) | 696 (97.6) | χ2=5.8, p=0.02 | |

| Provide adult inpatient care‖ | 410 (98.3) | 597 (84.3) | χ2=54.8, p<0.0001 | |

| Provide ICU/CCU care‖ | 237 (57.1) | 314 (44.8) | χ2=15.8, p<0.0001 | |

| Provide nursing home care‖ | 326 (78.4) | 524 (74.0) | χ2=2,7, p=0.10 | |

| Provide newborn nursery care‖ | 399 (95.9) | 513 (72.9) | χ2=91.8, p<0.0001 | |

| Provide pediatric inpatient care‖ | 307 (73.8) | 398 (56.6) | χ2=33.1, p<0.0001 | |

| Provide surgical inpatient procedures‖ | 126 (30.7) | 84 (12.1) | χ2=58.2, p<0.0001 | |

| Provide emergency room care‖ | 172 (41.8) | 240 (34.4) | χ2=5.93, p=0.01 | |

| Respondent Characteristic | Maternity Care Providers, M(SD) | Non-Maternity Care Providers, M(SD) | t(df), p | |

| Percent time: Direct patient care | 34.6±18.0 | 32.0±20.7 | t(1116)=2.15, p=0.03 | |

| Percent time: Research | 6.3±9.5 | 9.9±14.9 | t(924)=−4.1, p<0.0001 | |

| Percent time: Administration | 27.3±17.6 | 33.0±22.1 | t(1081)=−4.4, p<0.0001 | |

| Percent time: Teaching | 33.0±16.6 | 27.4±17.8 | t(1106)=5.2, p<0.0001 | |

| Percent time: Other | 6.5±10.6 | 8.8±14.6 | t(924)=−1.4, p<0.16 | |

| Years since residency graduation | 15.2±9.7 | 20.0±10.9 | t(1128)=−7.5, p<0.01 | |

Note. Where numbers do not add up to the total sample size, the remainder represent missing data.

The categories, “<30” and “30–39” were combined to “<40” due to fewer than 5 respondents in the <30 age range.

”Visiting Professor” and “Not Applicable (N/A)” were combined due to fewer than 5 respondents endorsing Visiting Professorships.

Only 1 respondent chose “Other”.

”Non-Academic Physician” and “Other” were combined due to fewer than 5 respondents endorsing “Non-Academic Physician”

The stem for this question was, “Do you OR any of your family physician practice partners provide the following services”

3.2. Perceived Prevalence

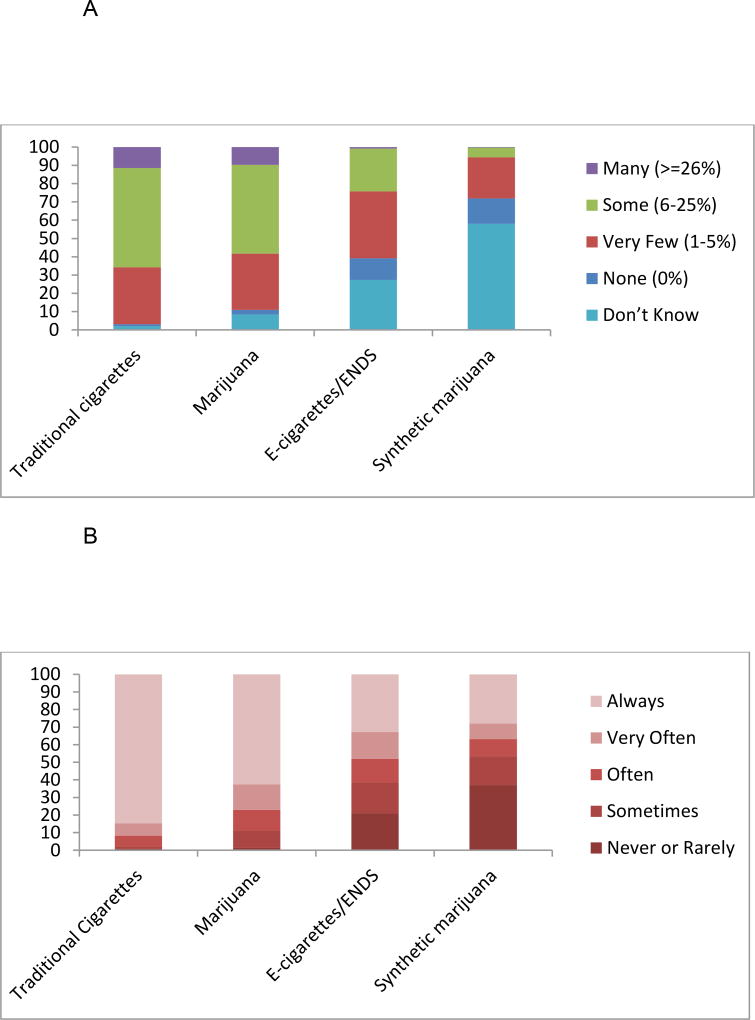

Providers most commonly reported that “some (6–25%)” of their pregnant patients used cigarettes and marijuana (see Table 2 and Figure 1A). Fewer providers selected “Some (6–25%)” for ENDS/e-cigarette use while pregnant, with “Very Few (1–5%)” chosen more frequently. Perceived NRT usage while pregnant was similar to providers’ endorsements for e-cigarettes. Nearly three-quarters of the sample selected that smoking-cessation medications (bupropion & varenicline) were likely used by “None (0%)” or “Very Few (1–5%)” of pregnant women. Slightly more than a third of providers (37%) selected, “Very few (1–5%)” or “None (0%)” for the prevalence of synthetic marijuana during pregnancy. However, provider uncertainty was common for synthetic marijuana (57% selected “Don’t Know”) and ENDS (27% chose “Don’t Know”). Slightly fewer providers selected “Don’t Know” for NRT (17%) and smoking-cessation medications (17%).

Table 2.

Provider Estimated Prevalence of Traditional Cigarettes, Marijuana, Synthetic Marijuana, E-Cigarettes/ENDS, NRT, and Smoking Cessation Medications (N=417)

| Response Options No. (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Question | None (0%) |

Very Few (1–5%) |

Some (6–25%) |

Many (≥26%)* |

Don’t Know |

P | |

| Pregnant patients <18† | 12 (3) | 144 (36) | 216 (54) | 25 (6) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 | |

| How many pregnant patients use: ‡ | |||||||

| Traditional cigarettes | 4 (1) | 122 (31) | 212 (54) | 45 (12) | 8 (2) | <0.0001 | |

| Marijuana | 10 (3) | 120 (31) | 190 (49) | 38 (10) | 33 (8) | <0.0001 | |

| Synthetic marijuana§ | 54 (14) | 88 (23) | 21 (5) | 1 (0) | 227 (58) | <0.0001 | |

| E-cigarettes (or other ENDS) | 46 (12) | 143 (37) | 92 (24) | 3 (1) | 107 (27) | <0.0001 | |

| NRT‖ | 70 (18) | 174 (45) | 80 (20) | 1 (0) | 66 (17) | <0.0001 | |

| Medications for smoking cessation¶ | 141 (36) | 145 (37) | 38 (10) | 1 (0) | 65 (17) | <0.0001 | |

Note. Where numbers do not add up to 417, the remainder represent missing data. “ENDS” = electronic nicotine delivery system; “NRT” = nicotine replacement therapy.

The response categories of “Many (26–50%)” and “Most (>50%)” were collapsed due to low endorsement (n<5) of the “Most (>50%)” category for all survey items.

“How many of your pregnant patients are <18 years of age?”

The full stem was, “In your practice, please estimate how many pregnant patients use the following:”

The full stem was, “Synthetic marijuana (e.g., K2, Spice)”

The full stem was, “Nicotine replacement therapy (e.g., patches, gum, lozenges, nasal spray, or inhaler)”

The full stem was, “Medication for smoking cessation (Bupropion [Zyban] or Varenicline[Chantix])”

Figure 1.

A Physician Perceptions of Prevalence of Traditional Cigarettes, Marijuana, E-cigarettes/ENDS, and Synthetic Marijuana for Pregnant Women.

B Physician Screening for Traditional Cigarettes, Marijuana, E-cigarettes/ENDS, and Synthetic Marijuana Among Pregnant Women.

3.3. Perceived Safety of Use during Pregnancy

Over 90% of providers tended to perceive that most substances/exposures assessed were generally unsafe while pregnant, with the exception of NRT. Over half (56%) of providers endorsed that NRT was safe to use during pregnancy (see Table 3). Further, a minority (27%) indicated that breastfeeding while smoking was safe.

Table 3.

Provider Perceptions of Safety for Pregnant Patients to Use Traditional Cigarettes, Marijuana, Synthetic Marijuana, E-Cigarettes/ENDS, NRT, or Breastfeed While Smoking (N=417)

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Survey Question* | Safe† | Unsafe† |

| Smoke cigarettes | 3 (1) | 386 (99) |

| Be exposed to SHS regularly | 13 (3) | 376 (97) |

| Smoke/use marijuana | 30 (8) | 359 (92) |

| Smoke/use synthetic marijuana | 3 (1) | 384 (99) |

| Use e-cigarettes/ENDS | 35 (9) | 352 (91) |

| Use NRT | 218 (56) | 171 (44) |

| Breastfeed while smoking | 103 (27) | 283 (73) |

Note. Where numbers do not add up to 417, the remainder represent missing data. “SHS”=secondhand smoke; “ENDS”=electronic nicotine delivery system; “NRT”=nicotine replacement therapy (e.g., patches, gum, lozenges, nasal spray, or inhaler).

The question stem was, “In your personal opinion, how safe is it for pregnant patients (during ANY trimester) to:”.

Response options included, “Very Safe, Safe, Somewhat Safe, Unsafe, or Very Unsafe.” Very safe, safe, and somewhat safe were collapsed to “Safe,” and unsafe and very unsafe were collapsed to “Unsafe,” for parsimony and due to low endorsement for some categories.

The largest proportion of providers felt ENDS/e-cigarettes have a lower cancer risk compared to traditional cigarettes (45.1%; n=176) with the remainder relatively evenly split between the two having the same level of risk (28.0%; n=109) or not having a lower risk (26.9%; n=105).

3.4. Screening Practices

Survey participants reported screening consistently (according to “Always” endorsements) for cigarette use (85%) and marijuana use (63%), with fewer than half of the sample screening for e-cigarettes/ENDS (33%) or synthetic marijuana (28%) consistently (see Table 4 and Figure 1B). Further, 48% reported screening consistently for SHSe in the home. Overall, fewer than a quarter (17.7%) of providers reported consistently screening for all four substances and SHSe. Nearly all providers (99.5%; n=388) reported using a patient-completed form or interview to screen for tobacco/nicotine use, with slightly fewer (95.6%; n=373) reporting this same method for screening for marijuana. A third of providers (31.5%; n=123) reported using laboratory screening for marijuana and very few providers reported using laboratory testing for tobacco/nicotine use (2.8%; n=11).

Table 4.

Provider Reported Screening for Traditional Cigarettes, SHS Exposure, Marijuana, Synthetic Marijuana, and E-Cigarette/ENDS (N=417)

| No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less-Consistent Screening | Consistent Screening |

||||

| Survey Question | Never or Rarely* | Sometimes | Often | Very Often | Always |

| How often screen pregnant patients for:† | |||||

| Use of traditional cigarettes | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 24 (6) | 27 (7) | 328 (85) |

| Presence of a smoker in home‡ | 10 (3) | 31 (8) | 54 (14) | 107 (28) | 184 (48) |

| Use of marijuana | 5 (1) | 38 (10) | 45 (12) | 56 (15) | 241 (63) |

| Use of synthetic marijuana | 133 (37) | 63 (16) | 38 (10) | 34 (9) | 108 (28) |

| Use of e-cigarettes/ENDS | 81 (21) | 68 (18) | 52 (13) | 59 (15) | 127 (33) |

Note. Where numbers do not add up to 417, the remainder represent missing data. “ENDS” = electronic nicotine delivery system.

“Never” and “Rarely” were collapsed due to low response endorsement (n<5) for several survey items, including cigarettes, presence of a smoker, and marijuana.

The full stem was, “In your practice, how often do you screen your pregnant patients (via ANY method: interview, patient-completed form, or laboratory testing) for the following:”

The full stem was, “Presence of a smoker (other than the pregnant patient) in the home”

3.5. Prescriptions/Recommendations for Smoking Cessation during Pregnancy

A majority of providers have recommended NRT (68.4%; n=267) to pregnant smokers who want to quit, with a third prescribing/recommending bupropion (30.8%; n=120), 6.7% (n=26) recommending/prescribing varenicline, and 4.4% (n=17) prescribing/recommending e-cigarettes to quit. A quarter (24.4%; n=95) reported that they have not prescribed nor recommended any of these as smoking cessation aids to pregnant women.

3.6. Patient Interest in ENDS and Recommendations on Recreational Marijuana

Providers most frequently indicated they are “never” (36.1%; n=140) or “rarely” (42.3%; n=164) questioned by pregnant patients about ENDS safety or smoking cessation efficacy. Regarding all other (non-pregnant) patients, physicians tended to report greater patient interest, by reporting “sometimes” (46.8%; n=182) or “frequently” (13.4%; n=52) being asked about e-cigarettes/ENDS.

Most providers reported they would recommend pregnant patients not use recreational marijuana (if it became legal or already is) in the providers’ states (97.2%; n=381) but fewer reported this for non-pregnant patients (70.4%; n=276).

4. Discussion

This study with family physicians who practice in academic settings and provide obstetrical care explored perceptions of prevalence, safety/risk, and current screening practices during pregnancy related to several inhalable substances (cigarettes, SHSe, marijuana, synthetic marijuana, and ENDS), as well as NRT and smoking-cessation medications. Over one-third of family physicians in academic settings reported providing labor and delivery services and this large population has significant responsibility for educating future physicians on appropriate screening practices with pregnant patients. Indeed, these providers’ perceptions of prevalence and safety/risk, and recommendations to patients regarding cigarettes (and SHSe), marijuana (and synthetic marijuana), ENDS, NRT, and smoking-cessation medications are likely to shape the screening practices of numerous trainees. Many of these providers perceived a significant proportion of pregnant women were using cigarettes, marijuana, and ENDS, consistent with prevalence estimates.19,20,50 These data also illustrated that many providers are also uncertain about the extent of synthetic marijuana use and to a lesser extent ENDS, among pregnant women under their care. Further, an overwhelming majority reported that all substance use/exposure surveyed was unsafe, with a slight majority (56%) reporting that NRT use during pregnancy was safe.

Many providers reported consistent screening for cigarette use during pregnancy (85%), in compliance with ACOG’s, AAFP’s, and USPSTF’s guidelines. This trend did not fully extend to SHSe during pregnancy, as 52% reported some SHSe screening inconsistency. Nearly two-thirds (63%) reported consistent screening for marijuana (recommended by ACOG), and 33% and 28% reported consistent screening for ENDS and synthetic marijuana, respectively, even in the absence of an existing guideline to do so. Nearly 1 in 5 providers (18%) reported screening consistently for all substances surveyed (including synthetic marijuana and SHSe), in line with our a priori predictions, demonstrating opportunity for increased screening during pregnancy. The overwhelming majority relied on patient report for screening, with a third utilizing laboratory testing for marijuana and fewer than 3% testing for nicotine’s major metabolite (cotinine) via urine screening. Use of a multiple-choice question for cigarette screening is valid and recommended52 and objective measures may further improve identification.13 Conversely, overreliance on self-report may miss a quarter (23%) of women using marijuana at their first prenatal visit.21 Universal laboratory screening is expensive, however, and likely contributes to its underutilization. Further, physicians may be reluctant to address substance use given legal mandates (varying across states) that may affect patient custody and may lack resources for assisting disadvantaged women.

Similar to others,36 almost half of our sample felt that ENDS/e-cigarettes carry less risk for cancer than traditional cigarettes. Further, survey respondents indicated that patients have expressed interest in ENDS’ safety and efficacy for smoking cessation, though less so for pregnant women. Accordingly, our sample reported low levels (<5%) of recommending e-cigarettes/ENDS as smoking cessation aids during pregnancy. Surprisingly, over half of the sample felt that NRT use by pregnant women was at least “somewhat safe,” despite evidence of fetal risks.42 Further, a sizable proportion reported prescribing bupropion and varenicline (with human studies currently lacking) for use during pregnancy. The majority (73%) perceived breastfeeding while smoking as unsafe, although minimal data supports risks to the infant from breastfeeding while the mother remains a smoker.53, 54 This survey item may need refinement, however, to delineate risks from tobacco constituents transmitted through breastmilk contrasted with SHSe risks from the mother.

The relatively high degree of consistent screening during pregnancy for cigarette use is encouraging but room for improvement exists for SHSe screening, given the well-established risks.9,10,12 Trends for marijuana screening were positive as well, given emerging health risks.22–24 Providers screening for or aware of synthetic marijuana use should recommend cessation, given high potential for harm.25 Providers are likely to increasingly face questions about ENDS with rising prevalence in younger adults;27 and, e-cigarette use surpassed traditional cigarette use in 2011–2015 among high school students, as cigarette use has declined in this group.55 While no guidelines currently exist for ENDS, the potential for neurodevelopmental harm is present. The lack of clear guidelines will undoubtedly pose challenges for providers who recommend cessation of all cigarette/ENDS use and exposure but may consider the use of ENDS, NRT or smoking-cessation medications for patients unable to quit cigarettes without assistance.

Ideally an evidence-based intervention (or referral) would dovetail with screening to reduce use and exposure across the substances surveyed. As reviewed in the Introduction, however, many of these substances lack empirically supported interventions or treatments to reduce use, and smoking cessation treatments during pregnancy have relatively modest effects. The relative lack of empirically supported treatments could influence providers’ willingness to screen for these substances, even though fewer than 10% of providers felt it was safe for patients to use these substances while pregnant. There is clearly an urgent need for more research to identify effective interventions for women using these substances during pregnancy.

These data represent a comprehensive assessment of family physicians in academic settings, who practice labor and delivery obstetrical care, regarding screening for smoking, SHSe, marijuana, and other substances but our study was not without limitations. No data were available on non-responders, precluding evaluations of sampling bias. Further, inclusion criteria limited our sample to physicians providing obstetrical care and these results may not generalize to physicians who provide prenatal care or have contact with pregnant patients during other primary care visits. By sampling physicians who provide obstetrical care, however, we assessed those with the greatest contact and in a position to deliver health-related messages to pregnant women. These self-reported, cross-sectional data should be interpreted with caution. Perceptions of prevalence and screening practices were not compared against objective data, such as health-record documentation of providers’ screening. Additionally, physician attitudes may change, as new data on marijuana, synthetics, and ENDS emerge and related legal decisions are continually issued (e.g., FDA regulation of e-cigarettes as tobacco products56).

5. Conclusions

This assessment of PCPs in academic settings, who provide obstetrical care, demonstrated that these providers perceive women are using the surveyed substances during pregnancy and that this use is unsafe. These data offer insight to the broader population of obstetrical providers’ screening practices for commonly used inhalable substances. Indeed, nearly all survey participants are teaching future generations of PCPs to provide obstetrical care, and responses highlight the opportunity for increased screening during pregnancy. Screening barriers in combination with the implementation of intervention/treatment should be explored in follow-on work. At a minimum, all pregnant patients could be asked about their use of these substances, as a starting point to both discover and mitigate potential harm. Existing evidence suggests recommendations to terminate use are appropriate. At present, it suffices to say that no amount of nicotine nor marijuana nor synthetic drug exposure is known to be safe in pregnancy and the risks of potential harm have not been fully evaluated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Drs. Northrup and Stotts had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. Dr. Northrup drafted the full proposal to the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance, performed all data analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All coauthors participated in proposal development, data interpretation, and manuscript revisions. The authors wish to thank the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance, specifically Drs. Lorraine Wallace and Arch (Chip) Mainous, and Ray Biggs, for help collecting these data. Dr. Northrup’s writing time was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (1R03HD088847; PI: T.F. Northrup) at the US National Institutes of Health and Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Stotts’ writing time was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL107404, PI=A.L. Stotts) at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Smoking cessation during pregnancy: A clinician's guide to helping pregnant women quit smoking. Washington, D.C: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Smoking cessation during pregnancy. [Accessed May 20, 2016];Committee Opinion 2010. 2010 Nov;:471. http://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co471.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20150819T1620161508.

- 3.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. [Accessed May 2, 2016];Committee Opinion. 2015 :637. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Marijuana-Use-During-Pregnancy-and-Lactation.

- 4.American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) [Accessed July 25, 2017];Clinical preventive service recommendation: Tobacco use. 2017 http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/tobacco-use.html.

- 5.US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [Accessed July 25, 2017];Final Update Summary: Tobacco Use in Adults and Pregnant Women: Counseling and Interventions. 2015 https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions.

- 6.US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [Accessed July 25, 2017];Final Recommendation Statement: Drug Use, Illicit: Screening. 2014 https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/drug-use-illicit-screening.

- 7.Shapiro B, Coffa D, McCance-Katz EF. A primary care approach to substance misuse. Am. Fam. Physician. 2013;88(2):113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. [Accessed July 25, 2017];Background paper on e-cigarettes (electronic nicotine delivery systems) 2013 http://escholarship.org/uc/item/13p2b72n.

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services. A report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Washington, DC: 2014. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress. [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox B, Martens E, Nemery B, Vangronsveld J, Nawrot TS. Impact of a stepwise introduction of smoke-free legislation on the rate of preterm births: analysis of routinely collected birth data. BMJ. 2013;346:f441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vicedo-Cabrera AM, Schindler C, Radovanovic D, et al. Benefits of smoking bans on preterm and early-term births: a natural experimental design in Switzerland. Tob. Control. 2016 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052739. tobaccocontrol-2015-052739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stotts AL, Northrup TF, Hutchinson MS, Pedroza C, Blackwell SC. Families at risk: Home and car smoking among pregnant women attending a low-income, urban prenatal clinic. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16(7):1020–1025. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wipfli H, Avila-Tang E, Navas-Acien A, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure among women and children: Evidence from 31 countries. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98(4):672–679. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Health and Human Services. Secondhand smoke: What it means to you. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Öberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, Peruga A, Prüss-Ustün A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. The Lancet. 2011;377(9760):139–146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: The ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(5):502–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerdá M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin D. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: Investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1):22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miech RA, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg J, Patrick ME. Trends in use of marijuana and attitudes toward marijuana among youth before and after decriminalization: The case of California 2007–2013. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2015;26(4):336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Creanga AA, Callaghan WM. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;213(2):201–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mark K, Desai A, Terplan M. Marijuana use and pregnancy: Prevalence, associated characteristics, and birth outcomes. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2016;19(1):105–111. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varner MW, Silver RM, Hogue CJR, et al. Association between stillbirth and illicit drug use and smoking during pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;123(1):113–125. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatr. Res. 2011;71(2):215–219. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Northstone K. Maternal use of cannabis and pregnancy outcome. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2002;109(1):21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Psychoyos D, Vinod KY. Marijuana, Spice 'herbal high', and early neural development: implications for rescheduling and legalization. Drug Test. Anal. 2013;5(1):27–45. doi: 10.1002/dta.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondrad E, Reid A. Colorado family physicians' attitudes toward medical marijuana. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2013;26(1):52–60. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.01.120089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramo DE, Young-Wolff KC, Prochaska JJ. Prevalence and correlates of electronic-cigarette use in young adults: Findings from three studies over five years. Addict. Behav. 2015;41:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigotti NA, Harrington KF, Richter K, et al. Increasing prevalence of electronic cigarette use among smokers hospitalized in 5 US cities, 2010–2013. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015;17(2):236–244. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jerry JM, Collins GB, Streem D. E-cigarettes: Safe to recommend to patients? Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2015;82(8):521–526. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.82a.14054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ginzel K, Maritz GS, Marks DF, et al. Critical review: Nicotine for the fetus, the infant and the adolescent? Journal of health psychology. 2007;12(2):215–224. doi: 10.1177/1359105307074240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM. The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;122(2):125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goniewicz ML, Lingas EO, Hajek P. Patterns of electronic cigarette use and user beliefs about their safety and benefits: an internet survey. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(2):133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. e-Cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102(9):1758–1766. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahr MK, Padgett S, Shope CD, et al. A qualitative assessment of the perceived risks of electronic cigarette and hookah use in pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2586-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baeza-Loya S, Viswanath H, Carter A, et al. Perceptions about e-cigarette safety may lead to e-smoking during pregnancy. Bull. Menninger Clin. 2014;78(3):243–252. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2014.78.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kandra KL, Ranney LM, Lee JG, Goldstein AO. Physicians’ attitudes and use of e-cigarettes as cessation devices, North Carolina, 2013. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e103462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinberg MB, Giovenco DP, Delnevo CD. Patient–physician communication regarding electronic cigarettes. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2015;2:96–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleman T, Cooper S, Thornton JG, et al. A randomized trial of nicotine-replacement therapy patches in pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366(9):808–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2013;382(9905):1629–1637. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi-Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015;(12):Cd010078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010078.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Food and Drug Adminstration. [Accessed July 25, 2017];Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling (Drugs) Final Rule. 2016 https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/labeling/ucm093307.htm.

- 42.Corelli RL, Hudmon KS. Medications for smoking cessation. West. J. Med. 2002;176(2):131–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley L, Watson L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009;3(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baxi R, Sharma M, Roseby R, et al. Family and carer smoking control programmes for reducing children's exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. The Cochrane Library. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001746.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gates PJ, Sabioni P, Copeland J, Le Foll B, Gowing L. Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder. The Cochrane Library. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005336.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terplan M, Ramanadhan S, Locke A, Longinaker N, Lui S. Psychosocial interventions for pregnant women in outpatient illicit drug treatment programs compared to other interventions. The Cochrane Library. 2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006037.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King BA, Pechacek TF, Mariolis P US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed July 25, 2017];Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs. 2014 2014 https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21697. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maxwell L, Mazzone M, Abercrombie S, et al. CERA: What? So what? Now what? The Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10(6):576–577. doi: 10.1370/afm.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mainous AG, III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director Survey. Fam. Med. 2012;44(10):691–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed July 25, 2017];PRAMS and smoking. 2013 https://www.cdc.gov/prams/tobaccoandprams.htm.

- 51.American Association for Public Opinion Research. [Accessed July 25, 2017];Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. (8). 2015 https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/AAPOR_Standard-Definitions2015_8theditionwithchanges_April2015_logo.pdf.

- 52.Mullen PD, Carbonari JP, Tabak ER, Glenday MC. Improving disclosure of smoking by pregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991;165(2):409–413. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90105-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dorea JG. Maternal smoking and infant feeding: Breastfeeding is better and safer. Matern. Child Health J. 2007;11(3):287–291. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ, Johnston M, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016;65(14):361–367. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.US Food and Drug Adminstration. [Accessed May 25, 2016];Tobacco products: Extending authorities to all tobacco products including e-cigarettes, cigars, and hookah. 2016 http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ucm388395.htm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.