Abstract

Cellular immune correlates conferring protection against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) but preventing vaccine-enhanced respiratory disease largely remain unclear. We investigated cellular immune correlates that contribute to preventing disease against human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) by nanoparticle vaccine delivery. Formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) vaccines and virus-like nanoparticles carrying RSV fusion proteins (F VLP) were investigated in mice. The FI-RSV vaccination caused severe weight loss and histopathology by inducing interleukin (IL)-4+, interferon (IFN)-γ+, IL-4+IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells, eosinophils, and lung plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs), CD103+ DCs, and CD11b+ DCs. In contrast, the F VLP-immune mice induced protection against RSV without disease by inducing natural killer cells, activated IFN-γ+, and IFN-γ+ tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α+ CD8+ T cells in the lung and bronchiolar airways during RSV infection but not disease-inducing DCs and effector T cells. Clodronate-mediated depletion studies provided evidence that alveolar macrophages that were present at high levels in the F VLP-immune mice play a role in modulating protective cellular immune phenotypes. There was an intrinsic difference between the F VLP and FI-RSV treatments in stimulating proinflammatory cytokines. The F VLP nanoparticle vaccination induced distinct innate and adaptive cellular subsets that potentially prevented lung disease after RSV infection.

Keywords: Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), Fusion Protein Nanoparticles, Alveolar Macrophages, Formalin-Inactivated RSV, Clodronate Liposome

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a major cause of lower respiratory tract infection, leading to severe bronchiolitis in infants.1 Each year, RSV infections cause 34 million cases, 3.4 million hospitalizations, and 66,000–199,000 deaths in children less than 5 years of age.2 Previous clinical trials revealed that vaccination with formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) resulted in the worsening of pulmonary disease in the lung of children following natural RSV infection.3,4 It has been demonstrated that the FI-RSV vaccine enhanced respiratory disease (ERD) is mainly due to the induction of aberrant T helper type 2 (Th2) and attenuated regulatory T cell responses.5–8 Additionally, soluble RSV fusion (F) protein vaccines were demonstrated to induce pulmonary disease after immunization and RSV infection.9,10 There is no licensed RSV vaccine.

The innate and adaptive cellular mechanisms that prevent vaccine-enhanced RSV disease after vaccination are poorly understood. Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are present most abundantly in alveolar spaces and play a key role in promoting immune surveillance and defense against respiratory infections.11–13 It is largely unknown how AMs modulate the immune responses in RSV vaccine-enhanced disease after vaccination and infection.

Virus-like nanoparticles containing RSV fusion proteins (F VLP) were produced by a recombinant baculovirus expression system in insect cells, resulting in spherical nanoparticles that were 60 to 120 nm in size, which is similar to the size of viruses.14 F VLP was shown to induce neutralizing antibodies and protect against RSV.14,15 Thus, F VLP vaccines could provide a unique system to identify the protective cellular immunity that correlates with conferring protection against RSV. In this study to determine the protective cellular immune correlates, we examined cellular dynamics of AMs, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells and T cells, which might be involved in protection and/or vaccine-enhanced disease after immunization with FI-RSV or F VLP, and then RSV infection. Additionally, clodronate-mediated depletion studies were performed to understand the roles of AMs in modulating the pulmonary innate and adaptive immune responses. Finally, the intrinsic properties of FI-RSV and F VLP vaccines were analyzed in terms of in vitro stimulation of DCs and macrophages to produce inflammatory cytokines.

RESULTS

F VLP-Immune Mice Do Not Induce RSV Disease Upon Infection as Assessed by Pulmonary Histopathology

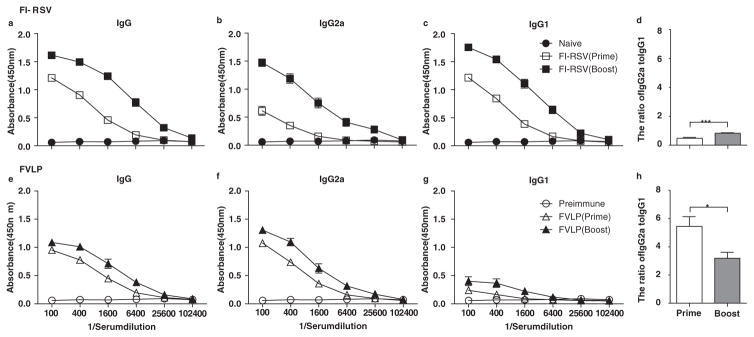

RSV F VLP was recently demonstrated to have spherical nanoparticles with diameters ranging from 60 to 120 nm14 and to induce RSV neutralizing antibodies, which conferred protection against RSV without causing pulmonary inflammatory disease.15 However, the specific immune cells that contribute to the RSV protection and prevent RSV disease still remain unknown. This study focused on identifying the phenotypes of the innate and adaptive immune cells that are responsible for protection and disease after vaccination with FI-RSV or F VLP. Serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies specific to RSV were determined with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Consistent with a previous study,14 the RSV specific IgG2a isotype antibody responses were predominantly induced in mice after vaccination with F VLP, suggesting a T helper type 1 (Th1) immune response (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Immunization with F VLPs induces Th1 type dominant antibody production. Mice (n = 10 in each set) were immunized with F VLP (10 μg/mouse) or FI-RSV (2 μg/mouse) at week 0 and boosted at week 4. RSV specific antibody levels were determined in the sera 3 weeks after the prime and boost immunization against inactivated RSV with ELISA and measured at OD 450 nm. Total IgG (a and e), IgG2a isotype (b and f), IgG1 isotype (c and g), and the ratio of IgG2a to IgG1 (d and h) were determined from mice immunized with FI-RSV (top) or RSV F VLP (bottom). An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to determine the statistical significance. Error bars indicate means± SEM. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

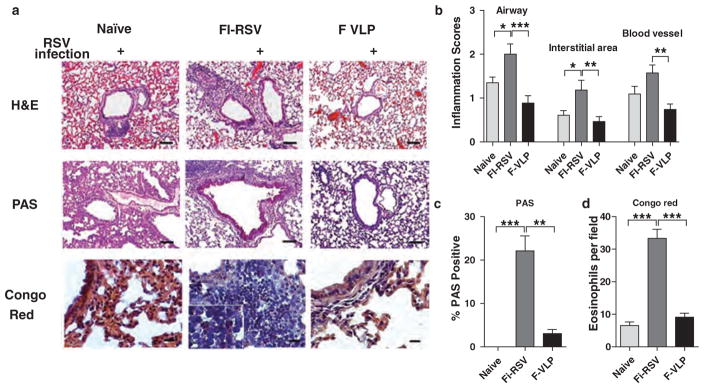

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of lung tissue sections was performed 5 days post RSV infection. The FI-RSV-immune mice displayed a high degree of infiltrating cell influx and thickened cell linings around the airways, interstitial areas, and blood vessels (Figs. 2(a and b)). Naïve mice showed a moderate level of cellular infiltrates around the airways and blood vessels whereas F VLP-immune mice did not show overt histopathology (Figs. 2(a and b)). Moderate histopathology was observed in naïve mice that were infected with RSV, which was consistent with previous studies.16 We also conducted periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining on the tissue sections to observe mucus production around the airways (Fig. 2(c)). Significantly high levels of mucus producing area around the airways were observed in the FI-RSV-immune mice, whereas the naïve and F VLP-immune mice did not show mucus production. Additionally, there were increased eosinophil numbers in the FI-RSV immune mouse lung tissue compared with those from the naïve and F VLP-immune mice (Fig. 2(d)). We observed a striking difference in the histopathology between the immunizations, in which FI-RSV induced severe RSV disease and F VLP prevented RSV disease. Therefore, we focused on determining the cellular parameters between the two immune mouse groups.

Figure 2.

F VLP-immune mice do not show pulmonary histopathology. The lung tissues were harvested from animals 5 days after RSV challenge (n = 5). The tissues were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin solution. (a) The tissues were embedded in paraffin and 5 μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), PAS, and congo red. (b) The inflammation scores on a scale of 0 to 3 were determined around the airways, interstitial areas, and blood vessels in the H&E stained tissue sections. (c) The bronchiolar mucus production scores were determined around the airways in the PAS stained tissues. (d) Eosinophilia was determined by congo red staining. The scale bars indicate 100 μm. H&E:hematoxylin and eosin; PAS: Periodic acid–Schiff. The data were reproducible with two independent experiments (n = 3). The one-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance. Error bars indicate means± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** < 0.001.

Lower Levels of Pulmonary Dendritic Cells Are Recruited in F VLP-Immune Mice

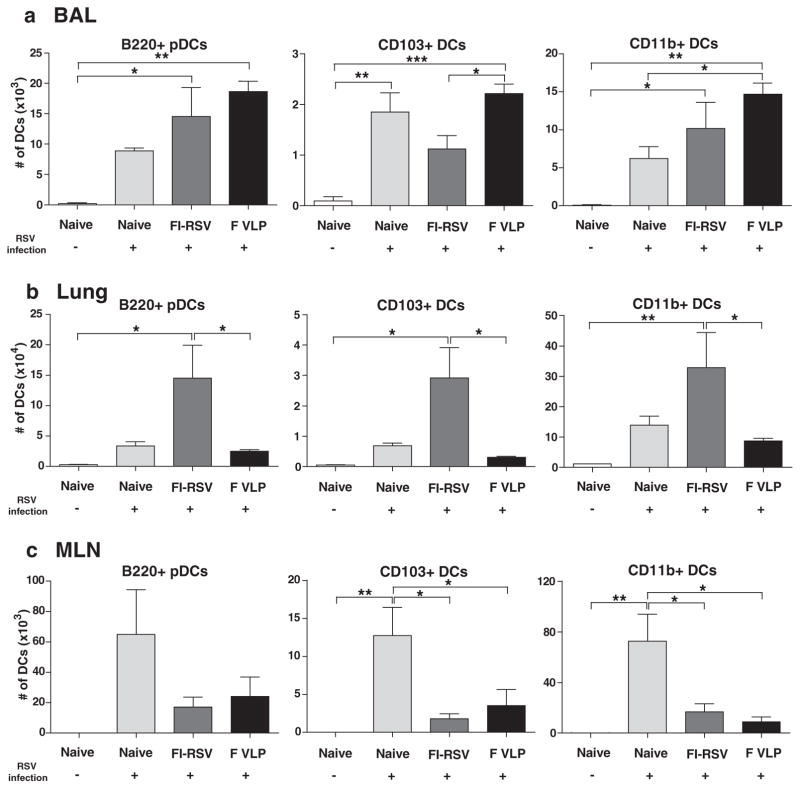

In comparison with FI-RSV, we focused on determining the protective immune cell changes that correlated with disease prevention in the F VLP-immune mice upon RSV infection. Dendritic cells (DCs) are key immune cells that connect between innate and adaptive immunity. Distinct DC subsets, such as CD11c+CD11b+ DCs, CD11c+CD103+ DCs, and CD11c+B220+ DCs, were observed at high levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from all of the RSV-infected mouse groups, as shown by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 3(a)). In particular, we observed higher cellularity of CD103+ DCs (CD103+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+) in the BAL of the RSV-infected F VLP mice compared with that of the FI-RSV immune mice (Fig. 3(a)). Additionally, plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs, B220+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+) and CD11b+ DCs (CD11b+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+) were recruited at higher levels in the F VLP group BALF than in the naïve group 5 days post infection.

Figure 3.

F VLP-immune mice recruit low levels of respiratory dendritic cell subsets into the lungs. The BALF and lung tissues from each group of mice (n = 5) were collected 5 days after RSV challenge. Distinct DC subsets were separated by flow cytometry analysis using the surface markers CD45, CD11c, CD11b, B220, and F4/80. B220+, CD103+, and CD11b+ DCs. Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs, B220+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+), CD103+ DCs (CD103+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+), and CD11b+ DCs (CD11b+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+) were analyzed in the BALF (a), lungs (b), and MLN (c). BAL:bronchoalveolar lavage; MLN: mediastinal lymph nodes. The data are representative of two independent experiments. A One-way ANOVA was used to determine the statistical significance. Error bars indicate means±SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Notably, the F VLP-immune mice showed significantly lower pDC, CD103+ DC, and CD11b+ DC numbers in the lungs compared with those in the FI-RSV-immune mice (Fig. 3(b)). A trend of lower pDC, CD103+ DC and CD11+DCs subset cellularity was found in the lungs of naïve mice upon RSV infection compared with the FI-RSV-immune mice (Fig. 3(b)). Considering a 10-fold higher scale cellularity presented in the lungs, significantly higher pDC, CD103+ DC, and CD11b+ DC levels (Fig. 3(b)) were observed in the lungs of FI-RSV-immune mice with severe weight loss and pulmonary inflammation compared with the F VLP-immune mice. These results imply that DC populations that are recruited to the lung at high levels contribute to RSV disease in FI-RSV-immune mice. Additionally, it appears that the F VLP-immune mice modulated recruitment of pulmonary DC subsets into the lung at low levels to prevent inflammatory disease upon RSV infection.

Next, to further determine whether different immune conditions influenced DC migration into the draining lymph nodes (dLNs) 5 days after RSV challenge, the numbers of different DC subsets were analyzed in the mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs). Higher pDC, CD103+DC, and CD11b+DC numbers were detected in the MLNs of naïve mice compared with those in the FI-RSV- or F VLP-immune mice at 5 days post RSV infection (Fig. 3(c)). These results suggest that higher lung RSV loads in naïve mice may be associated with respiratory DC migration into the MLNs.

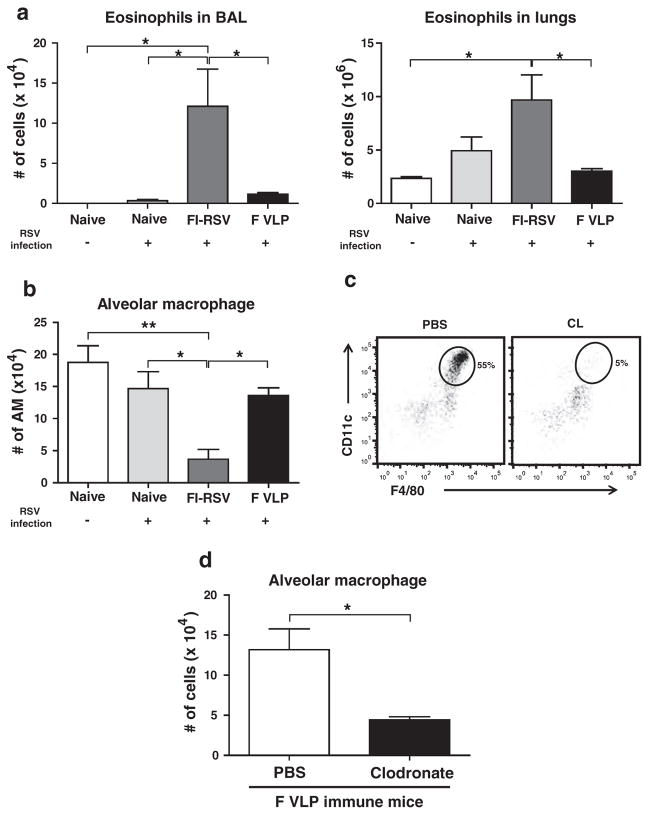

F VLP-Immune Mice Maintain Alveolar Macrophages at Higher Levels Than FI-RSV-Immune Mice Upon RSV Infection

The F VLP-immune mice showed only a background level of eosinophils in the BALF and lungs, which are similar to those in uninfected naïve mice upon RSV infection (Fig. 4(a)). In contrast, the highest eosinophil levels were observed in the BALF and lungs of the FI-RSV-immune mice, 5 days post RSV infection. Interestingly, AMs were found to be present at significantly higher levels in the airways from uninfected naïve, RSV infected naïve, and F VLP-immune mice than those from FI-RSV-immune mice (Fig. 4(b)). To better understand the possible role of alveolar macrophages in preventing vaccine-enhanced diseases from F VLP-immune mice, F VLP-immune mice were treated with clodronate liposome (CL) prior to RSV infection, which is known to selectively deplete AMs.17–18 Approximately 91% of the AM populations were depleted in the BALF from the F VLP-immune mice after the CL treatment prior to RSV infection as determined using surface markers (CD11c+CD11b−F4/80+) (Fig. 4(c)).19 As a result of the CL treatment, the RSV infected F VLP-immune mice revealed a 3-fold decrease in the AM cellularity in the airways (Fig. 4(d)). Taken together, the F VLP-immune mice maintained lower eosinophil levels and higher AM levels in the airways compared with FI-RSV-immune mice, and CL treatment prior to RSV infection resulted in lower AM cellularity in the BALF of F VLP-immune mice.

Figure 4.

RSV infection significantly recruits eosinophils but down-regulates alveolar macrophages in FI-RSV immune mice. Immune cells were harvested from the BALF and lungs of mice 5 days post RSV challenge (n = 5). Flow cytometry was used to analyze the immune cell infiltration. (a) The eosinophil (CD11c−CD11b+SiglecF+) and (b) total AM numbers (CD11c+CD11b−F4/80+) were determined in each mouse group. (c) The AM depletion in the F VLP-immune mice was confirmed by flow cytometry. (d) Clodronate treatment depletes AMs from F VLP-immune mice. At 6 weeks after boost immunization, mice immunized with F VLP (n = 5/group) were treated with clodronate liposome (CL) 4 hours prior to RSV infection. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) treated mice were included as a control in each group. One-way ANOVA or an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests were used to determine the statistical significance. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars indicate means±SEM. #P < 0.05 (between FI-RSV and F VLP-immune groups treated with PBS). *P < 0.05.

Alveolar Macrophages Partially Contribute to Protection Against RSV Disease of Weight Loss in F VLP-Immune Mice

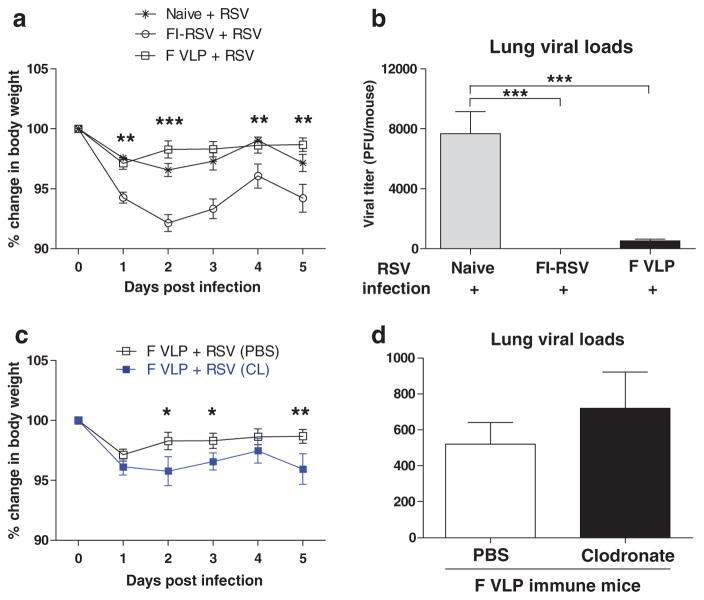

After RSV infection, we monitored body weight changes of mice (Fig. 5(a)). Consistent with a previous study,20 the unimmunized naïve group showed moderate weight loss of approximately 3 to 4%. The FI-RSV immunized group after RSV infection revealed prominent weight loss of approximately 8% at day 2 (Fig. 5(a)). The F VLP immunized group showed approximately 3% weight loss on day 1 post-infection and then immediately recovered from the body weight loss 2 to 5 days after the RSV infection (Fig. 5(a)). In contrast, the CL-treated F VLP mice exhibited a significant delay in recovery from the body weight loss compared with the PBS-treated F VLP mice (Fig. 5(c)).

Figure 5.

Alveolar macrophages contribute to protection in F VLP-immune mice against weight loss. Unimmunized naïve, FI-RSV-immune, PBS- and CL-treated F VLP-immune mice were challenged with RSV (1 × 106 PFU). Lung samples from each mouse group (n = 5) were harvested 5 days post RSV challenges. (a) Body weights were monitored daily. (b) Viral titers in the lungs (individual, n = 5 were determined with an immunoplaque assay. (c) Body weights from the F VLP-immune mice were compared between mice that were or were not CL treated. (d) Lung viral loads were compared between the PBS- and CL-treated F VLP mice. Representative data of two independent experiments (n = 5 in each set) are presented. One-way ANOVA or an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests were used to determine the statistical significance. Error bars indicate means ± SEM. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To further assess the roles of AMs in the protection against RSV, the viral loads were determined 5 days post-infection. High RSV titers were detected in the lungs of the naive group with RSV infection (Fig. 5(b)). RSV titers were not detected in the FI-RSV-immune group and were significantly lower in the F VLP-immune mice (Fig. 5(b)). There was no significant difference in the lung viral loads between the PBS- and CL-treated F VLP-immune mice (Fig. 5(d)). These results suggest that AMs may play a role in preventing weight loss upon RSV infection in F VLP-immune mice and the RSV-specific humoral immune response is mainly responsible for viral clearance in vaccinated mice.

Alveolar Macrophages Regulate Natural Killer Cell, Eosinophil, and Pulmonary Dendritic Cell Recruitment in F VLP-Immune Mice

Upon RSV infection, the F VLP-immune mice showed only a background level of eosinophils in BALF and lungs, which were similar to those in uninfected naïve mice (Fig. 4(a)). Importantly, we found that CL treatment in the F VLP-immune mice resulted in 6- and 7-fold increases in the BAL and lung eosinophil numbers, respectively, 5 days after RSV infection (Fig. 6(a)). Because NK cells play a role in killing virus infected cells,21 we analyzed the possible effects of AM depletion on NK cell recruitment in lungs by the surface markers (CD49b+CD3−).22 The F VLP mice showed relatively higher NK cell levels in the airways compared with the FI-RSV group (data not shown); however, the CL-treated F VLP-immune mice showed a significant decrease in the numbers of activated NK cells (CD49b+CD3−CD69+) in the BALF (Fig. 6(b)). In contrast to the airways, the activated NK cell levels in the lungs were observed at similar levels in the PBS- and CL-treated F VLP-immune mice (Fig. 6(b)). As a result of the CL treatment, the numbers of BAL pDCs and CD11b+ DCs were significantly reduced in the F VLP-immune mice (Fig. 6(c)), indicating a potential role for AMs in recruiting these DC subsets. In contrast to the reduced pDC and CD11b+ DC numbers in the BALF of the F VLP-immune mice, three distinct DC subsets (pDCs, CD103+ DCs, and CD11b+ DCs) were significantly increased in the F VLP-immune mouse lungs as a result of CL treatment prior to RSV infection (Fig. 6(d)). However, these numbers of lung DCs in the F VLP mice with AM depletion were significantly lower than those in the FI-RSV-immune mice (Fig. 3). Interestingly, although AM depletion resulted in altering cell recruitment into the airways and lungs of the F VLP-immune mice, these factors did not significantly influence the overall pulmonary histopathology upon RSV challenge (Fig. 6(e)). These results suggest that F VLP-immune mice recruit NK cells, pDCs, and CD11b+ DCs but not eosinophils into the airways. The AMs in the airways of F VLP-immune mice might play a role in recruiting NK cells, pDCs, and CD11b+ DCs and in reducing eosinophil infiltration into the airways during RSV infection.

Figure 6.

F VLP-immune mice recruit natural killer cells, but not eosinophils, into the airways. Immune cells were harvested from the BALF and lungs of CL-treated and PBS (mock control)-treated F VLP mice 5 days post RSV challenge (n = 5). Flow cytometry was used to analyze the immune cell infiltration. (a) Eosinophils (CD11b+CD11c−SiglecF+). The eosinophil frequencies and numbers were analyzed by using CD11c and Siglec F antibodies. (b) CD69+ NK cells. The CD49b marker was used to gate NK cells. Activated NK cells were further analyzed by evaluating CD69 marker expression. Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs, B220+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+), CD103+ DCs (CD103+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+), and CD11b+ DCs (CD11b+CD11c+F4/80−CD45+) were analyzed in the BALF (c) and lungs (d) of F VLP- immune mice after CL treatment. (e) The inflammation scores on a scale of 0 to 3 were determined around the airways, interstitial areas, and blood vessels in the H&E stained tissue sections. Representative data are shown from two independent experiments. The unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to determine the statistical significance. Error bars indicate means± SEM. *P < 0.05; ** < P < 0.01; *** < P < 0.001.

Alveolar Macrophages in F VLP-Immune Mice Recruit T Cells into the Airways But Not into the Lungs

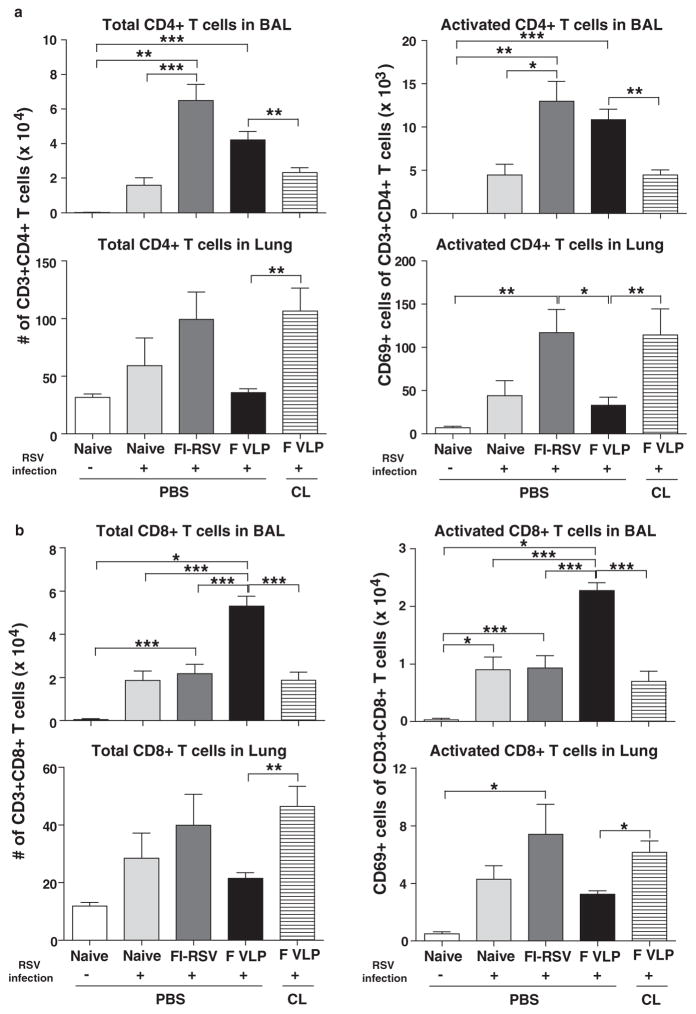

To characterize whether adaptive T cell immune responses are involved in RSV disease, the numbers of activated T cells were analyzed in the airways and lungs after RSV infection using the surface marker CD69+.23 The highest numbers of total and activated CD4+ T cells (CD3+CD4+CD69+) were observed in the BALF and lungs from the FI-RSV-immune mice (Fig. 7(a)). Interestingly, the F VLP-immune mice displayed significantly lower activated CD4+ T cell levels in the lungs (Fig. 7(a)), which appeared to correlate with lower lung DC subpopulation levels (Fig. 3(b)). The CL treatment resulted in significantly increased total CD4+ and activated CD4+ T cells in the lungs from F VLP-immunized mice, but a reverse pattern was observed in the BALF (Fig. 7(a)).

Figure 7.

F VLP vaccination induces high CD8+ T cells in the airways and low CD4+ T cells in the lungs upon RSV infection. Immune cells were isolated from the BALF and lungs 5 days post RSV infection and used for flow cytometry analysis (n = 5/group). (a) The total number of CD3+CD4+ T cells was quantified in the BALF and lungs. Activated CD3+CD4+ T cells were further determined by using CD69 as an activation marker. (b) The total number of CD3+CD8+ T cells was analyzed in the BALF and lungs and further separated into activated cells by evaluating CD69 expression. Representative data from two independent experiments (n = 5 in each set) are presented. CL: CL-treated F VLP-immune mice. One-way ANOVA or an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests were used to determine the statistical significance. Error bars indicate means± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The F VLP-immune mice showed the highest numbers of total CD8+ and activated CD8+ T cells in the airways compared with those in the naïve and FI-RSV-immune mice upon RSV infection, which were reduced as a result of the CL treatment in the F VLP group (Fig. 7(b)). In the lung cells, the CD8+ T cells, which were at a low level in the F VLP-immune mice, were increased as a result of CL treatment, and this was consistent with CD4+ T cell mobilization (Fig. 7(b)). These results suggest that significantly low levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lung as well as relatively high levels of CD8+ T cells in the airways play an important role in preventing RSV disease in F VLP-immune mice upon RSV infection. These results provide convincing evidence that AM populations in the airways of F VLP-immune mice might be associated with modulating pulmonary CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in between the airways (BAL) and the lungs.

F VLP-Immune Mice Induce Airway IFN-γ+ and TNF-α+ CD8+ T Cells but not IL-4+CD4+T Cells

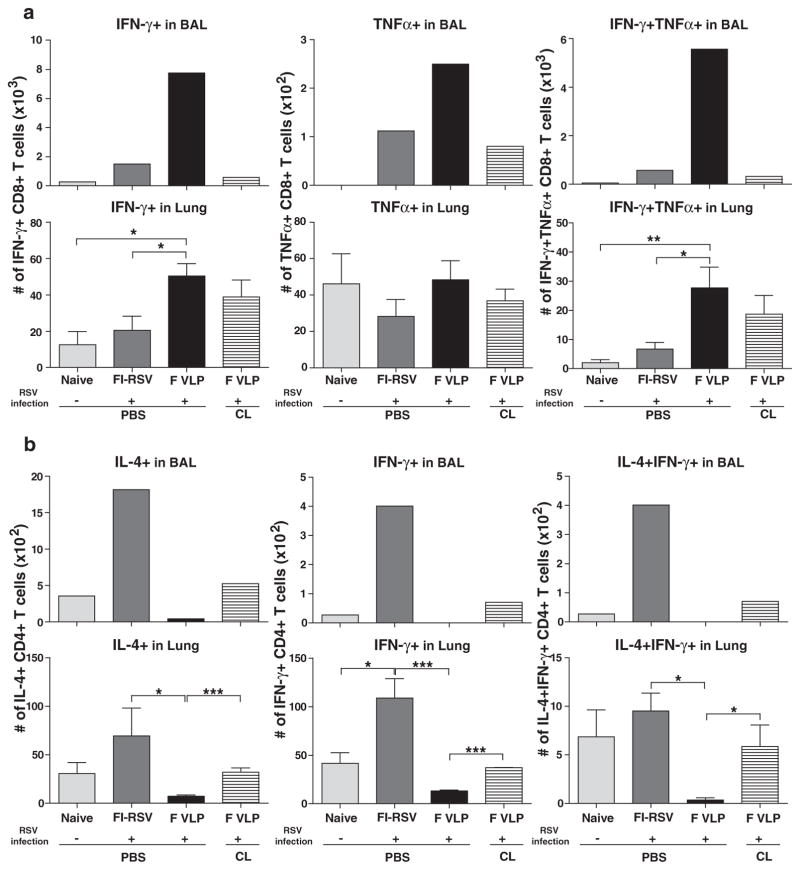

To further specify whether the absence of AMs influenced antigen-specific T cell responses, the cells from the airways and lungs 5 days post RSV challenge were in vitro (KYKNAVTEL).24 and stimulated with the RSV F85–93 G183–195 (WAICKRIPNKKPG) peptides, which are specific for CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively.25 Cytokine producing T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 8). Significantly higher numbers of IFN-γ+, TNF-α+, and dual IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells specific for the F peptide were detected in the airways of F VLP-immune mice compared with those in naïve or FI-RSV-immune mice (top panel, Fig. 8(a)). Additionally, F-specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ+ and IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ were found at higher levels in the lungs from F VLP immunized mice compared with naïve or FI-RSV immune mice (bottom panel, Fig. 8(a)). The depletion of AMs prior to RSV infection resulted in a reduction of Th1 cytokine producing CD8+ T cells in the airways of the F VLP-immune mice, but not in the lungs 5 days post RSV challenge (Fig. 8(a)).

Figure 8.

FI-RSV and F VLP vaccines differentially modulate antigen-specific effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in the airways and lungs. Immune cells were collected from the BALF and lungs of vaccinated mice 5 days after RSV challenge (n = 5/group). The cells were in vitro stimulated in the presence of RSV F85–93 (KYKNAVTEL) or RSV G183–195 (WAICKRIPNKKPG) peptides. Cytokine-producing cells were determined by an intracellular cytokine staining flow cytometry assay using anti-IL-4, -IFN-γ, and -TNF-α antibodies. After F or G peptide stimulation, the total cytokine-producing CD8+ T (a) or CD4+ T (b) cell numbers were determined in the BALF and lung samples of each group. The cells from the BALF of each group were pooled (n = 53. CL: CL-treated F VLP-immune mice. Representative data from two independent experiments (n = 5 in each set) are presented. One-way ANOVA or an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests were used to determine the statistical significance. Error bars indicate means± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

After in vitro stimulation with the G peptide, the F VLP-immune mice showed low IL-4+ or IL-4+IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cell levels in the airway and lung samples (Fig. 8(b)). In contrast, the BALF and lung samples from the FI-RSV-immune mice had significantly higher CD4+ T cell numbers that were producing IL-4+, IFN-γ+, or IL-4+ IFN-γ+ cytokines compared with naïve or F VLP mice (Fig. 8(b)). Interestingly, AM depletion from the F VLP-immune mice led to significant increases in IL-4+, IFN-γ+, and IL-4+IFN-γ+ cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells in the BALF (top panel, Fig. 8(b)) and lungs (bottom panel, Fig. 8(b)). These data suggest that the highest IL-4-producing Th2 cell levels in the BALF and lungs from FI-RSV-immune mice are important contributors to severe pulmonary immunopathology (Fig. 2). These cells were not induced in the F VLP-immune mice. It is likely that AM populations in the airways of F VLP-immune mice modulate Th1 and Th2 cytokine-producing effector CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in between the airways and lungs. Taken together, the F VLP-immune mice preferentially induced single IFN-γ+ and dual IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells and inhibited the induction of CD4+ T cells that produced IL-4+, IFN-γ+, or IL-4+IFN-γ+ cytokines, which likely prevented RSV disease during RSV infection.

Intrinsic Differences Between FI-RSV and F VLP Vaccines in Stimulating Dendritic Cells and Macrophages

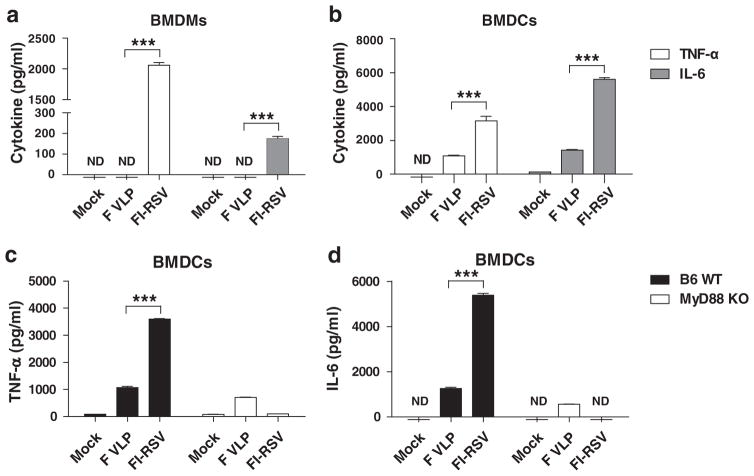

The underlying mechanisms by which the FI-RSV and F VLP vaccines prime the Th2 and Th1 biased host immune responses respectively remain unknown. To gain insight into the unknown mechanisms, we evaluated the TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine levels in the culture supernatants of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) after in vitro stimulation with F VLP or FI-RSV vaccines. F VLP did not stimulate BALB/c mouse derived BMDMs to produce tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6 (Fig. 9(a)). In contrast, FI-RSV was highly effective in stimulating BMDMs to produce high TNF-α levels and moderate IL-6 levels (Fig. 9(a)). Additionally, 3 to 4-fold higher TNF-α and IL-6 levels were secreted into FI-RSV culture supernatants of BMDCs from C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice compared with those in the F VLP cultures, respectively (Figs. 9(b and c)). Interestingly, the TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine production in the FI-RSV-stimulated BMDCs was severely impaired over 95% or not detected in BMDCs from myeloid differentiation gene 88 (MyD88)-deficient mice (Figs. 9(c and d)). However, F VLP was found to stimulate BMDCs to produce relatively low TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine levels in a MyD88 signaling independent manner (Figs. 9(c and d)). These results suggest that there are intrinsic differences between the FI-RSV and F VLP vaccines in stimulating the production of inflammatory cytokines by BMDCs and BMDMs in vitro, respectively, and that FI-RSV stimulates DCs to produce inflammatory cytokines in a MyD88 signaling-dependent manner.

Figure 9.

FI-RSV and F VLP vaccines show intrinsic differences in stimulating dendritic cells and macrophages to produce inflammatory cytokines. Bone marrow cells from BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were harvested and cultured in the presence of GM-CSF or M-CSF to differentiate the cells into BMDCs or BMDMs, respectively. (a) BMDMs and (b) BMDCs from BALB/c mice were further stimulated with purified FI-RSV or F VLP vaccines and cytokine levels (TNF-α and IL-6) were determined with ELISAs from the culture supernatants. (c) TNF-α and (d) IL-6 levels were analyzed from BMDCs that were obtained from C57BL/6 and MyD88 deficient mice. The data were pooled from 2 independent experiments (n = 3 each set). An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to determine the statistical significance. Error bars indicate means± SEM. ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

RSV neutralizing antibodies contribute to protection by clearing lung viral loads and there is a licensed neutralizing antibody drug (Palivizumab) that is specific for RSV F.26,27 Since the tragic failure of the FI-RSV vaccine clinical trials, safety is one of most challenging obstacles in developing an RSV vaccine. The FI-RSV-immune mice showed severe pulmonary histopathology despite effective lung viral clearance upon RSV challenge infection, which is consistent with previous studies.28–30 However, the innate and adaptive cellular immune populations that are responsible for preventing RSV disease ERD are not well understood and there is not yet a licensed vaccine. F VLP was previously demonstrated to induce IgG2a isotype dominant antibodies, and RSV neutralizing activity, and to confer protection against RSV as evidenced by lowered lung viral loads.14,15 Consistent with these previous studies, FI-RSV primed Th2 type IgG1 dominant antibodies, whereas F VLP dominantly primed Th1 type IgG2a isotype antibody responses (Fig. 1). Pulmonary histology results indicated that F VLP did not induce ERD, as was reported in a recent study.15 However, the FI-RSV-immune mice demonstrated overt weight loss and severe inflammatory histopathology as evidenced by high cellular infiltrates, mucus production, and eosinophilia, suggesting ERD induction. It is unknown how the FI-RSV and F VLP vaccines predominantly prime the Th2 and Th1 host immune response respectively, resulting in differential pulmonary inflammation outcomes after vaccination and infection. In vitro culture studies showed that there were intrinsic differences between the FI-RSV and F VLP vaccines in stimulating DCs and macrophages to produce TNF-α and IL-6 inflammatory cytokines. FI-RSV but not F VLP stimulated DCs in a MyD88 dependent manner. This has significant implications for choosing an adjuvant for RSV vaccines that avoids histopathology upon RSV infection. Further studies are required to better understand how these differences in stimulating DCs and macrophages might be correlated with RSV protection and/or disease in vivo. Here, we focused on understanding the innate and adaptive immune cell components that are responsible for preventing ERD after F VLP vaccination and RSV infection.

Despite effective lung viral clearance, the FI-RSV-immune mice showed severe body weight loss and histopathology. Lung viral clearance in the absence of body weight loss and histopathology is an important surrogate of protection against RSV. Our data support the finding that vaccination with F VLP induced protective immune responses, as no severe body weight loss and histopathology were observed after RSV challenge. We also found significantly different mobilizations of innate immune cells such as different DC subsets, eosinophils, and AMs in the airway spaces (BALF) and lung parenchyma of FI-RSV-or F VLP-immune mice after RSV challenge. DC subsets including B220+ pDCs, CD103+ DCs, and CD11b+ DCs in the FI-RSV-immune mouse lungs were detected at the highest levels. In contrast, pDCs, CD103+ DCs, and CD11b+ DCs were found at the lowest levels in the F VLP-immune mouse lungs. These results suggest that high levels of different DC populations in the lung parenchymal tissues are likely to contribute to inflammatory RSV disease, resulting in severe weight loss and histopathology as evidenced in the FI-RSV-immune mice. The naïve mice showed moderate levels of B220+ pDCs, CD103+ DCs, and CD11b+ DCs in the BALF and lungs after RSV infection. In particular, the highest mobilization level of DC subtypes into the draining lymph nodes was observed in the RSV-infected naïve mice probably due to high lung viral loads, which is as consistent with previous studies.31,32 In line with a previous study,15 the highest eosinophil infiltration levels into the lungs were observed in FI-RSV-immune mice but not in the F VLP-immune mice, which is a characteristic of RSV vaccine enhanced disease. Interestingly, the AMs in the airways from the naïve and F VLP-immune mice were maintained at relatively high levels upon RSV infection. In contrast, the AMs from FI-RSV-immune mice were detected at the lowest levels after RSV infection. We do not know the mechanism by which F VLP vaccination prevents a decrease in macrophages in the airways. FI-RSV vaccination induces higher levels of antibody binding to the whole RSV particles compared with F VLP vaccination,33 suggesting more RSV-immune complexes upon challenge. Thus, resident macrophages in the airways of FI-RSV-immune mice might be more prone to apoptosis by phagocytosis of RSV-immune complexes. Alternatively, the AMs with immune complexes are likely to move away from the airways into the lung tissue of FI-RSV-immune mice, which contributes to ERD. A future direction will be to address this mechanism, and it will be highly informative to determine AM levels in Fc receptor deficient mice after vaccination and challenge. Additionally, the eosinophil and neutrophil (granulocyte) infiltration levels were very high in the FI-RSV-immune mice after RSV infection.34 A previous study demonstrated that neutrophil depletion in naïve mice resulted in a decrease in inflammation without changes in the AM population after RSV infection.35 However, it remains unknown whether neutrophil and/or eosinophil abrogation influences the AM populations in FI-RSV vaccinated mice. This study suggests that the differential distribution of innate immune cells between the airways and the lung parenchymas plays a role in the protection against RSV or RSV disease. Extremely high infiltrations of pDCs, CD103+ DCs, and CD11b+ DCs located in the lungs rather than in the airways are likely to be the innate immune cellular phenotypes that are responsible for RSV disease in FI-RSV primed immune mice after infection in addition to high eosinophils and Th2 adaptive responses.

Although AMs have been studied in naïve mice after viral infection,20 their roles in previously vaccinated mice after viral challenge have not been investigated. To better understand the possible roles of AMs in the innate and adaptive immune responses that contribute to RSV protection and/or disease, CL treatment prior to RSV infection was employed in this study. The CL administration in the F VLP mice resulted in a significant depletion of AMs. The CL treatment in the F VLP-immune mice prior to RSV infection caused more overt and consistent weight loss. The results from CL treatment of the F VLP-immune mice support evidence that AMs play a role in differentially modulating Th1 and Th2 cytokine-secreting effector T cells in the airways and lung parenchymas. A similar reverse pattern in modulating B220+ plasmacytoid DCs and CD11b+ DCs in between the airways and lungs was observed in CL-treated F VLP-immune mice compared with PBS-treated F VLP-immune mice (data not shown). From the analysis of the F VLP-immune mice with and without CL treatment in comparison with control FI-RSV-immune mice that were induced with severe ERD, we found multiple innate and adaptive immune cells that were responsible for conferring protection and preventing RSV disease. Additionally, it is worth noting that an appropriate distribution of these cellular immune populations in between the airway surfaces and the lung parenchymal interstitium is implicated to be important for preventing ERD.

We observed an interesting correlation between the AM and T cell population changes in the BALF (airways) and lung samples from the F VLP-immune mice. High AM levels were found to be correlated with prominent CD8+ and CD4+ T cells levels in the F VLP-immune mouse airways because the effects of the CL treatment on the F VLP-immune mouse AM populations were faithfully reflected in lowering T cells in the airways and on increasing T cells in the lungs. Additionally, reduced pulmonary DC numbers (pDCs and CD11b+ DCs) may modulate infiltration of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells into the airways of F VLP-immune mice following CL treatment. Therefore, these observations suggest that low CD4+ and high CD8+ T cellularity as well as AM and pulmonary DC populations in the airways rather than in the lungs can be immune correlates that contribute to preventing severe pulmonary histopathology and weight loss in F VLP-immune mice.

Different types of T cells and cytokines play critical roles in RSV pathogenesis after vaccination and RSV infection. Single IFN-γ+ and dual IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells in the BALF and lungs were unique adaptive T cells that were observed in the F VLP-immune mice that did not show pulmonary histopathology. Low AM levels in the airways from CL treated F VLP-immune mice correlated with reduced IFN-γ+ CD8+ T and IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ CD8+ T cell levels. Additionally, a small population of IL-4+ and IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells was induced in the BALF and lungs under these conditions. Antigen presenting cells were shown to be required to reactivate memory T cell responses in the respiratory tracts.36 These cellular changes, including reduced bronchiolar CD8+ T cells and increased CD4+ T cells, might be a parameter that contributes to weight loss in F VLP-immune mice with CL treatment. In support of this, high levels of IL-4+, IFN-γ+, and dual IL-4+IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells in the airway and lung tissues were found to be major adaptive cellular factors that correlated with weight loss and lung inflammatory RSV disease in the FI-RSV-immune mice.

In summary, the results of this study suggest that airway AMs from F VLP-immune mice might have multiple roles in controlling eosinophil infiltration into the airways and lungs, in modulating airway NK cells, and in protecting against body weight loss. Additionally, specific DC subsets (pDCs, CD11b+ DCs) that were found in the airways (but not in the lungs) of F VLP-immune mice might have contributed to recalling airway IFN-γ+ and IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ CD8+ T cell responses. In contrast to the F VLP-immune mice, the FI-RSV-immune mice had altered levels of disease-inducing innate and adaptive cell populations, including low AM levels and high eosinophil and lung DC subset levels (e.g., pDCs, CD103+ DCs, and CD11b+ DCs), which might have subsequently contributed to the excessive levels of IL-4+, IFN-γ+, IL-4+IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells in the lungs. Despite the phenotypic similarity, the AMs and pulmonary DC subsets from the F VLP-immune mice may have intrinsic differences compared with those from FI-RSV-immune mice based on their differential induction of high levels of IFN-γ+ and IFN-γ+TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells in the airways and lungs. A better understanding of the intrinsic differences between F VLP and FI-RSV in the stimulation of DCs and macrophages to produce inflammatory cytokines is expected to provide insight into the design and development of safe RSV vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and FI-RSV

To obtain the respiratory syncytial virus (A2 strain), RSV was grown in 80–90% confluent HEp-2 cells for 3 days at 37 °C. The HEp-2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) containing 2% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. After culturing for 3 days, the RSV was then harvested from the infected HEp-2 cells and ultracentrifuged for 1 hr at 8 °C.14,28 The RSV was inactivated by incubating with 10% formalin (1:400 vol/vol) for 3 days at 37 °C. Then, the formalin inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) was further purified by ultracentrifugation. FI-RSV was confirmed by an immunoplaque assay.

Virus-Like Nanoparticles Carrying RSV F Proteins (F VLP)

F VLP was produced in Sf9 insect cells that were co-infected with recombinant baculovirus (rBV) expressing influenza M1 matrix protein and rBV that expressed the full-length RSV F protein as described.14 Briefly, culture media containing released F VLP was harvested and ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min. The F VLP was then further purified with a discontinuous sucrose gradient (20%–30%–60%). Under the electron microscopic examination, the F VLP displayed a spherical morphology of nanoparticles with 60 to 120 nm diameter in size.14

Immunization, Clodronate Liposome Treatment, and Viral Infection

BALB/c mice (n = 10 per group, 6–8 weeks old, Harlan) were anesthetized by isoflurane and intramuscularly (i.m.) immunized with FI-RSV (2 μg proteins with alum adjuvant 4 mg/ml) or F VLP (10 μg) in 100 μl of PBS per mouse at weeks 0 and 4. At 6 weeks after boost immunization, half (n=5) of the F VLP immunized mice were intranasally (i.n.) treated with 30% clodronate liposome (CL) (Clodronate Liposomes, Netherlands) 4 hrs prior to RSV challenge. Immune mice were anesthetized with isoflurance and i.n. challenged with the RSV A2 strain (1 × 106 PFU) in 50 μl of PBS per mouse. Body weight was monitored daily for 5 days. To compare the vaccination and CL treatment efficacies, F VLP-immune mice (n = 5) with and without CL treatment were used as additional control groups. Two independent sets of mice were used for creating the reproducible experimental data and assay results described in this study. All of the animal studies were approved and conducted under Georgia State University’s IACUC guidelines.

Flow Cytometry and Intracellular Cytokine Staining

To collect the non-adherent cells from the airways, BALF was harvested using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The lung tissues were homogenized, and the cells were then separated with Percoll gradients. Frosted glass microscope slides were used to make cell suspensions from tissues, including the MLNs and spleens. To perform the flow cytometric analysis, surface marker antibodies including CD3 (17A2), CD4 (RM4–5), CD8 (53–6.7), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), CD45 (30-F11), F4/80 (BM8), CD49b (DX4), CD69 (H1.2F3) and Siglec F (E50-2440) (eBioscience or BD Pharmingen) were used to distinguish the cell populations. To determine the antigen-specific T cell responses, cells from the BALF and lungs were (KYKNAVTEL)24 and stimulated with synthetic F85–93 (WAICKRIPNKKPG)25 peptides in the presence G183–195 of brefeldin A (BFA) at 37 °C for 5 hrs. Intracellular cytokine levels were measured by using monoclonal antibodies against IL-4 (BVD6-24G2), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), and TNF-α (MP6-XT22). The samples were acquired using a Becton-Dickinson LSR-II/Fortessa flow cytometer (BD, San Diego, CA) and the results were analyzed using the Flowjo software (Tree Star Inc.).

RSV Immunoplaque Assay

RSV lung viral titers were determined with an immunoplaque assay as described previously.14 Briefly, lung extracts were serially diluted in DMEM and cultured on HEp-2 cell monolayers for 3–5 days at 37 °C. RSV infected HEp-2 cells were treated with 5% neutral buffered formalin for 30 minutes. To increase the visualization of the RSV infected plaques, anti-F monoclonal antibody (Millipore) was used and then the plaques were developed with a DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) HRP substrate kit (Invitrogen).

Lung Histopathology

The lung tissues were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 hrs and were transferred into 70% ethanol. The tissues embedded into paraffin were cut into 5 μm sections, followed by a routine process. The sectioned tissues on each slide were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) as well as periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS) as previously described.37,38

In Vitro Culture of BMDCs and BMDMs

BMDCs and BMDMs were obtained from BALB/c, C57BL/6, and MyD88 gene deficient (MyD88−/−) mice. The MyD88−/− mice were maintained as described previously.39,40 For the preparation of immature BMDCs or BMDMs, bone marrow cells were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 20 ng/ml mouse recombinant granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (Invitrogen) or 25 ng/ml macrophage colony stimulating factor (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN) for 6–10 days at 37 °C. The BMDCs and BMDMs (2 ×105cells/well) were stimulated with F VLPs or FI-RSV adsorbed aluminum hydroxide, and a medium control for 20 hrs. The cytokine levels from the culture supernatants were determined with ELISA.

Statistical Analysis

All of the results are presented as the means ± SEM (standard error of mean). The statistical significance was determined with one-way ANOVA or two-tailed Student’s t tests for all of the experiments. We analyzed all of the data with the Prism statistical software (GraphPad software Inc., San Diego, CA). P values, as indicators for statistically significant differences, are shown with horizontal lines (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID grants AI105170 (Sang-Moo Kang), AI093772 (Sang-Moo Kang), and AI119366 (Sang-Moo Kang).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Smyth RL, Openshaw PJ. Lancet. 2006;368:312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins PL, Graham BS. J Virol. 2008;82:2040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01625-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapikian AZ, Mitchell RH, Chanock RM, Shvedoff RA, Stewart CE. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89:405. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HW, Canchola JG, Brandt CD, Pyles G, Chanock RM, Jensen K, Parrott RH. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89:422. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson TR, Graham BS. J Virol. 1999;73:8485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8485-8495.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson TR, Parker RA, Johnson JE, Graham BS. J Immunol. 2003;170:2037. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loebbermann J, Durant L, Thornton H, Johansson C, Openshaw PJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217580110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy BR, Prince GA, Walsh EE, Kim HW, Parrott RH, Hemming VG, Rodriguez WJ, Chanock RM. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:197. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.2.197-202.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bembridge GP, Lopez JA, Bustos R, Melero JA, Cook R, Mason H, Taylor G. J Virol. 1999;73:10086. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10086-10094.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garlapati S, Garg R, Brownlie R, Latimer L, Simko E, Hancock RE, Babiuk LA, Gerdts V, Potter A, van Drunen Littelvan den Hurk S. Vaccine. 2012;30:5206. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon SB, Read RC. Br Med Bull. 2002;61:45. doi: 10.1093/bmb/61.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tumpey TM, Garcia-Sastre A, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, Swayne DE, Pantin-Jackwood MJ, Schultz-Cherry S, Solorzano A, Van Rooijen N, Katz JM, Basler CF. J Virol. 2005;79:14933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14933-14944.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broug-Holub E, Toews GB, van Iwaarden JF, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL, Paine R, 3rd, Standiford TJ. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1139. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1139-1146.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quan FS, Kim Y, Lee S, Yi H, Kang SM, Bozja J, Moore ML, Compans RW. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:987. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, Quan FS, Kwon Y, Sakamoto K, Kang SM, Compans RW, Moore ML. Antiviral Res. 2014;111:129. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham BS, Anderson LJ. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;372:391. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thepen T, Van Rooijen N, Kraal G. J Exp Med. 1989;170:499. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Rooijen N, Bakker J, Sanders A. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:178. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(97)01019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall JD, Woolard MD, Gunn BM, Craven RR, Taft-Benz S, Frelinger JA, Kawula TH. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5843. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01176-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pribul PK, Harker J, Wang B, Wang H, Tregoning JS, Schwarze J, Openshaw PJ. J Virol. 2008;82:4441. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02541-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raulet DH. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:129. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arase H, Saito T, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. J Immunol. 2001;167:1141. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YT, Suarez-Ramirez JE, Wu T, Redman JM, Bouchard K, Hadley GA, Cauley LS. J Virol. 2011;85:4085. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02493-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang J, Srikiatkhachorn A, Braciale TJ. J Immunol. 2001;167:4254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varga SM, Wissinger EL, Braciale TJ. J Immunol. 2000;165:6487. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geevarghese B, Simoes EA. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:201. doi: 10.3851/IMP2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkatesh MP, Weisman LE. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006;5:261. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ko EJ, Kwon YM, Lee JS, Hwang HS, Yoo SE, Lee YN, Lee YT, Kim MC, Cho MK, Lee YR, Quan FS, Song JM, Lee S, Moore ML, Kang SM. Nanomedicine. 2015;11:99. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang HS, Kwon YM, Lee JS, Yoo SE, Lee YN, Ko EJ, Kim MC, Cho MK, Lee YT, Jung YJ, Lee JY, Li JD, Kang SM. Antiviral Res. 2014;110:115. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prince GA, Curtis SJ, Yim KC, Porter DD. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:2881. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Immunity. 2003;18:265. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smit JJ, Rudd BD, Lukacs NW. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1153. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S, Quan FS, Kwon Y, Sakamoto K, Kang SM, Compans RW, Moore ML. Antiviral Research. 2014;111C:129. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee YT, Kim KH, Hwang HS, Lee Y, Kwon YM, Ko EJ, Jung YJ, Lee YN, Kim MC, Kang SM. Virology. 2015;485:36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stokes KL, Currier MG, Sakamoto K, Lee S, Collins PL, Plemper RK, Moore ML. J Virol. 2013;87:10070. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01347-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zammit DJ, Cauley LS, Pham QM, Lefrancois L. Immunity. 2005;22:561. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyerholz DK, Griffin MA, Castilow EM, Varga SM. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37:249. doi: 10.1177/0192623308329342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang HS, Kwon YM, Lee JS, Yoo SE, Lee YN, Ko EJ, Kim MC, Cho MK, Lee YT, Jung YJ, Lee JY, Li JD, Kang SM. Antiviral Res. 2014;110C:115. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Immunity. 1998;9:143. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang SM, Yoo DG, Kim MC, Song JM, Park MK, Quan EOFS, Akira S, Compans RW. J Virol. 2011;85:11391. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00080-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]