Abstract

Purpose

Despite recommendations for early entry into human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care, many people diagnosed with HIV delay seeking care. Multiple types of social support (ie, cognitive, emotional, and tangible) are often needed for someone to transition into HIV care, but a lack of emotional support at diagnosis may be the reason why some people fail to stay engaged in care. Thus, the purpose of this study was to identify how people living with HIV conceptualized emotional support needs and delivery at diagnosis.

Method

We conducted a secondary analysis of qualitative data from 27 people living with HIV, many of whom delayed entry into HIV care.

Results

Participants described their experiences seeking care after an HIV diagnosis and identified components of emotional support that aided entry into care – identification, connection, and navigational presence. Many participants stated that these types of support were ideally delivered by peers with HIV.

Conclusion

In clinical practice, providers often use an HIV diagnosis as an opportunity to educate patients about HIV prevention and access to services. However, this type of social support may not facilitate engagement in care if emotional support needs are not met.

Keywords: linkage to care, engagement in care, social support, qualitative

Introduction

In 2013, Florida had the second highest number of people diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the USA, and although 86% of this population were linked to care upon diagnosis, only 55% were engaged in care after 1 year.1 People are considered linked to care if they visit a health-care provider about their HIV status within 3 months of diagnosis and are engaged in care if they regularly visit a provider.2,3 In order to realize the full potential of antiretroviral treatment (ART) as a prevention intervention, we need to reach the goal of about 85% of people diagnosed with HIV linked to and engaged in care.4,5 Therefore, we need to better understand factors associated with HIV care linkage and continued engagement in care.

In the South, people newly diagnosed with HIV may not link to HIV care immediately following diagnosis for several reasons including poverty, lack of health insurance, failure to invest in HIV information, criminalization of HIV exposure, weak safety net programs, and hostility toward the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities.6 Social support has also been identified as a factor that influences linkage and HIV care engagement. Social support is multifaceted and is often defined in multiple ways, such as type of support (emotional, cognitive, tangible) or delivery of support (informal or formal).7 Emotional support focuses on the provision of comfort for an individual and fosters feelings of security. Cognitive (or informational) support is related to teaching and conveying information, and tangible support emphasizes the provision of goods.8

Extant literature demonstrates that the type of support provided at diagnosis influences linkage and engagement in care outcomes. A recent study that examined social support as a predictor of early diagnosis, linkage, retention, and adherence to HIV care concluded that emotional support was not a significant predictor of linkage to care outcomes.9 Instead, overall social support was found to be a predictor of early HIV diagnosis whereas the subdomain of tangible support was associated with linkage to care and ART adherence. In our previous research, we found that participants with HIV in Florida stressed a need for emotional support at diagnosis and the type, timing, and delivery of support impacted entry into care.10 Other HIV-related research has identified the need for emotional support during the care continuum. Pakenham evaluated support behaviors among a continuum of gay men and described several emotional supportive behaviors that the participants found helpful including having someone available, accepting/understanding, nurturing, and self-disclosing.11 Collectively, these findings indicate that emotional support may be an overlooked, complex, and important factor in facilitating linkage and engagement in care. Thus, in the proposed study, we sought to build on these findings by identifying how people living with HIV (PLWH) conceptualized (or operationalized) emotional support needs and delivery at the time of diagnosis. To achieve this aim, we conducted a secondary analysis of a qualitative grounded theory study on linkage and engagement in HIV care. Results will help determine how providers and support staff can help people newly diagnosed with HIV enter and remain engaged in care.

Methods

This research was a secondary analysis of a qualitative grounded theory study on the factors influencing the decision to seek and maintain HIV-related health care among PLWH.10 Grounded theory methods are appropriate for investigating social processes such as a decision-making process to seek care.12 The research was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection.

Sample

For the primary study, a combination of convenience and snowball sampling was used to recruit participants from the community in north central Florida. Participants were included in the study if they were >18 years, could speak English, and had a diagnosis of HIV. There were no exclusion criteria. Three groups of participants were initially targeted for recruitment – people who delayed care 9 months or more, people who moved immediately into care, and those who never received care, although we were unable to recruit from this last group. At the time of study design, 3 months was considered the target for linkage to care; however, we chose 9 months because of possible delays in reporting or enrollment in services.13 In keeping with the tenets of grounded theory, we chose to use the participants’ perceptions of when they considered themselves as linked to and/or engaged in HIV care. As recommended by a community advisory board, participants were recruited from local support groups, planning councils, health departments, and a university-based community agency that seeks to connect community members to research studies. Since the first author was involved in HIV advocacy in the community, a few of the participants were known prior to data collection. Each participant completed one interview and, at the end of interview, received a $25 gift card to compensate for time, transportation, and parking.

Data collection

Data collection for the primary study consisted of in-depth, semi-structured qualitative interviews conducted by the first author who was trained in grounded theory methodology. All interviews took place in a private setting at a location convenient to both participant and interviewer. The question guide for the original study was published elsewhere; however, initially questions focused on the decision process to engage in HIV care and questions evolved as a result of ongoing analysis.10 In later interviews, during theoretical sampling, if support was mentioned, the interviewer asked participants to describe what they meant by support and probed for the different types of support (ie, cognitive, emotional, and tangible), if not mentioned. Conversely, if support was not specifically mentioned, at the end of the interview, the interviewer described findings about support from earlier interviews and asked participants about their perceptions of the kinds of support that are needed at diagnosis to engage people in care. Furthermore, the interviewer asked participants who had been helpful to them during the decision process of linking to HIV care. Interviews continued until the theoretical model from the primary study was complete (ie, participants did not have anything more to add to the developing model) and saturation was reached.

Data analysis

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed by a professional transcriptionist. Transcriptions from the original interviews were spot-checked for accuracy and an error rate >5% necessitated re-transcription of the interviews; however, no transcription met this criteria. A qualitative data analysis management program, NVivo 10™, was used to manage transcripts, coding, memos, and literature specific to linkage and engagement in care. For the primary study, techniques in grounded theory guided the process of analysis and included methods by Glaser and Strauss, Strauss and Corbin, and Dimensional Analysis.14–16 Methods for the primary study are described in detail elsewhere.10

As the concept of support emerged after analysis of the first 12 interviews, we decided to reexamine the interviews to understand the types of support evident in the process (tangible, emotional, and cognitive) that were coded in the analysis of the primary study. Using NVivo 10, we gathered all data where participants discussed any type of support. Next, two of the authors independently recoded the support data, specifically identifying passages that met a broad definition of emotional support “offering comfort in times of stress, showing care and concern” and identified who was instrumental in delivering the support that helped them engage in care.17 During the recoding process, the analytical team met weekly to discuss coding and resolve any differences. After coding specifically for emotional support, we organized codes by similar themes and then collapsed these codes into final themes presented in this paper.

To enhance credibility and determine saturation, we used peer debriefing through the presentation of data and conclusions to the Health Science Center Qualitative Research Colloquium. This group, comprising expert faculty and graduate students with experience in qualitative methods and backgrounds in public health, nursing, and disability research, meets biweekly to review and critique qualitative proposals, analysis, and publications from faculty and student research. The analytical team developed reflexive journals to determine if personal thoughts and feelings may have influenced the decision-making process and findings during the analysis.

Results

Study participants included 13 men, 13 women, and 1 transgender person. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. They ranged from ages 25 to 64 years and represented a variety of HIV transmission categories, including rape, blood transfusion, heterosexual activity, and sexual activity between men. Education levels varied from less than a high school education to a master’s degree. Participants had been diagnosed with HIV between 2 months and 27 years. Ten of the participants entered care immediately after diagnosis and 17 of the participants delayed care between 1 and 15 years after diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographics

| N=27 | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 13 |

| Female | 13 |

| Transgender | 1 |

| Age group | |

| 25–34 | 3 |

| 35–44 | 8 |

| 45–54 | 9 |

| 55–64 | 6 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Race | |

| Black or African American | 16 |

| White | 8 |

| Other | 2 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-hispanic | 24 |

| Hispanic | 2 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school diploma | 8 |

| High school diploma | 10 |

| Some college | 3 |

| Associates degree | 3 |

| Bachelors | 0 |

| Graduate degree | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Number of years with HIV | M =13.2 (SD =8.4) |

| Time to care | |

| Delay | 17 |

| Immediate | 10 |

| Place of diagnosis | |

| Health department | 11 |

| Jail | 4 |

| Plasma/blood center | 2 |

| Rehabilitation center | 2 |

| Physician’s office | 5 |

| Hospital | 2 |

| Free testing site | 1 |

| Transmission category | |

| Substance use | 9 |

| MSM | 10 |

| Rape | 3 |

| Blood transfusion | 1 |

| Heterosexual | 4 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Support was described in the context of grief and crisis after initial diagnosis. When participants described their diagnosis, they expressed it was a time of grief and crisis. For example, one woman recalled

I know it happened to me and it’s the worst thing and I never will forget it. And it’s the worst thing to ever happen to me in my life, you know (you’ve) told me I’m positive and now you’ve left me to think about this. And you didn’t even give me a number to call anybody.

Participants articulated that emotional support was essential to help them immediately during the crisis and grief period following diagnosis.

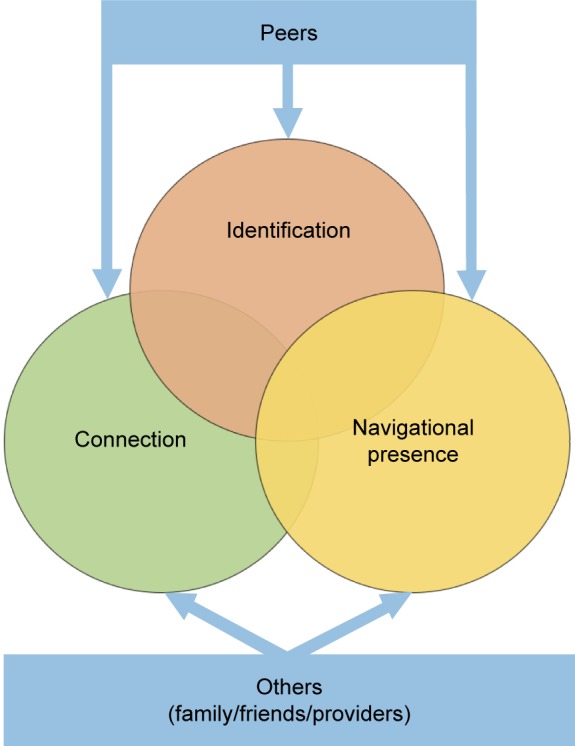

Three unique components of emotional support emerged from the data, including identification (receiving empathy and knowing that others were like them), connection (receiving ongoing reassurance and comfort from a health-care provider), and navigational presence (having a support person while entering care). A summary of the emotional support concepts and examples of relevant quotes are provided in Table 2. While these concepts were described independently, they were not identified in isolation and are often interrelated with each other as shown in the model (Figure 1). When discussing who was the best person to deliver emotional support, participants stated that a peer advocate (someone with HIV) was ideal to deliver emotional support but it could also be delivered through HIV support groups, family member(s), friend(s), or professional health-care providers (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Themes and supporting data

| Type of support | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | Knowledge of others with HIV can enhance feelings of identification and belonging after diagnosis | People want to know they are not the only one. I wanted to know that I wasn’t the only one in this situation |

|

| ||

| Connection | Health-care providers should maintain contact while offering reassurance and comfort | They (providers) communicate with their clients, especially the case managers. They check on their clients. They check on their appointments. They check on their lab works |

|

| ||

| Navigational presence | Someone to be there with them through the process of linkage and not necessarily telling them where they needed to go next. This can be described as engaged presence | I just couldn’t deal with this. She was my good support. My daughter was there, we’ll make it, you know? She went to the doctor with me and they talked with me and the case manager was very good. Both the doctors was, you know, give me good spirit |

|

| ||

| Delivery | A peer is the ideal person to offer social support at the time of diagnosis; however, health-care providers may refer people newly diagnosed with HIV/AIDS to peers or local support groups | Peers that’s livin’ with it and medical people, they need, both needs to come in at the same time, not just medical cuz medical people really don’t understand. I guess they would understand but they just … |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Figure 1.

Types and delivery of emotional support.

Identification

Participants described identification as receiving empathy or knowing that similar people also had a diagnosis of HIV. Furthermore, they expressed that identification with others was a prerequisite to engagement in care. For example, one woman talked about attending a spa outreach day for HIV-positive women prior to entering care to see how others were living with the virus:

And I saw other people that were living with the virus, they were happy. They were okay in their skins, I hadn’t made it there yet […] but when I met other people that were living with it and they were truly striving where they were in their skins […]. I need someone that’s dealing with what I’m dealing with, that understands, that’s compassionate but strong. I don’t need someone that’s not gonna put me on the right track […]. I met people right out front in the health department – they were HIV positive and haven’t (told anyone) – and I tell them that I am and they grab me and they hug me and we cry out there. And they say I’m, you know, I’m positive too and they say it so quietly.

One male participant described how he identifies with people at a local HIV support group as follows:

And I try to talk to a lot of people that have been positive way longer than me. That’s why I love coming here, and I know the ones that have had it for a long time, and who has it, you know. And I like to talk to them, say, you know, how you feel? What is your feelings? You know, uh, do you go through stress? Are you depressed sometimes? Do you feel lonely or do you feel guilt, or do you feel that you should’ve never got into the gay scene?

Participants also identified with celebrities who disclosed their HIV status, and indicated that they felt a reduction in shame after seeing a celebrity cope with the diagnosis in a positive way. For example, one man who had a hard time entering care recounted the following:

[…] don’t touch me. I don’t wanna; I don’t want you to do nothin’. And one particular day we were sitting there and my wife called me in and Magic was talking about it. And I kinda looked at him and I was like, wow, this man is still holding it together. And I was wondering, can I do that? Can I actually, you know, hold it together, be active, and look at people with a smile?

Connection

To maintain connection, participants felt that someone should offer reassurance and comfort. For example, one participant described her need as the following:

They could just be there holding my hand, and just say it’s gonna be all right, ought to be good enough for me. I don’t know about somebody else, but for me that would be good enough […]. And you gonna – immediately want – what I did – immediately wanted somebody to – to hold me, and I cried on their shoulders.

Connection through touch could also have a positive impact on provider–patient interactions as described by one participant when she was diagnosed with HIV:

[…] that lady don’t know me from squat and she’s there, you know, consoling me, and hugging me, and crying me, and just really, it helped out. That helped out.

However, connection did not have to be provided through physical touch; instead, it could be provided through regular, empathetic communication after diagnosis. Another participant described the ongoing connection with the provider that helped her connect with care. In this interaction, the participant felt accepted and valued:

She never put me down. She always was there for me. If I needed, she made provisions for me. Even if I didn’t even have any contact with her, she says, “I’ve got something for you. I need you to come get it.” And I would be there.

But the thing is they cared, they wasn’t just doctors or nurses, they really cared and my social worker was very caring. I had good support. They didn’t back down. She would literally call me, how ya doin’ today, you feelin’ all right and she talked to me. When I had this colostomy thing she literally came, she called me, do you mind if I come by and talk with you?

Several participants felt that the best way to maintain a sense of connection was through peer support, which helped them feel less alone. For example, one woman described how providers could help people newly diagnosed with HIV/AIDS feel connected as follows:

And take me, walk me to the peer as living with this, introduce me and let them know this person here has just been diagnosed. And I’m bringing you to this person here because they understand because they’re living with it […] because if a person tests positive they need to be able to connect with someone that’s positive to me.

When asked, “What kind of support do you need from health-care providers at the time of diagnosis?”, a male participant responded as follows:

I believe that they would need comfort from good friends, somebody that they know that’s kind that can understand as somebody that doesn’t judge you. They can accept you the way you are and just tell them, hey, look – I’m here 24 hours a day. Call me, we’ll talk. I don’t care however long we need to talk on the phone. We’ll go out to a movie. We’ll go sit down and have some dinner somewhere. We’ll go hang out. We’ll do something fun.

[…] almost like NA or AA meetings. You have a sponsor. You call them in the middle of the night, and whenever you’re wanting to relapse. They say, hey, why don’t we go catch us movie? Why don’t we go out to dinner somewhere and do something?

Navigational presence

Generally, patient navigation refers to directing people toward resources for care; however, in the context of emotional support, participants stated that they needed emotional support during the process of navigation to HIV care. One participant talked about how someone from the health department came to check on him and helped him overcome his barrier to care – depression.

And then I got really depressed. And they picked me up one day from home, and I hadn’t did anything. I was just sitting there in a corner. And I knew it was [name] but I never forget it. She said, “[participant’s name], what is going on here?” I just looked at her. So she and this other guy, they took me to the Health Department and we sat there and finally she got me to talk, to open up to her […]. And I just told her, “I’m just going through too much. You know, I just, I just don’t want to deal with this no more.” That’s when they put me on antidepressant pills which worked because in two weeks I was seeing a big difference.

I just couldn’t deal with this. She was my good support. My daughter was there, we’ll make it, you know? She went to the doctor with me and they talked with me and the case manager was very good. Both the doctors was, you know, give me good spirit.

Delivery of emotional support

Emotional support may be delivered by peers with HIV, health-care providers, friends, or family members, but several participants stated navigation by peers with HIV would be ideal since peers with HIV truly understand the experience. For example, one woman commented as follows:

And take me, walk me to the peer as living with this, introduce me and let them know okay this person here has just been diagnosed. And I’m bringing you to this person here because they understand because they’re living with it.

However, participants noted that providers could deliver emotional support as long as they also referred patients to peers with HIV or local support groups. In this way, patients would receive support both during medical appointments and leisure time, enhancing their likelihood of engaging in care.

Discussion

We conducted a secondary analysis of qualitative data in order to better understand the types of emotional support needed at diagnosis that can assist providers and public health officials in facilitating entry and engagement into HIV care. Our analysis identified three unique components of emotional support needed following an HIV diagnosis: identification, connection, and navigational presence. Each of these may be essential, but distinct components that will promote linkage and engagement in care.

For many, being informed of a positive HIV test creates a crisis and feelings of grief.10 When someone receives bad news, such as an HIV diagnosis, feelings of crisis or grief can temporarily alter normal ways of coping.18,19 Providers may attribute a lack of seeking care to structural or individual barriers; however, people diagnosed with HIV describe emotional barriers as a reason for not seeking care.20 Jacobson explains that when people are in a crisis, such as what someone may experience during an HIV diagnosis, they may not differentiate between the types of social support being offered.7 He argues that emotional support is most needed during the time of crisis or grief, and therefore, people newly diagnosed with HIV may not be able to comprehend other types of support that are being offered at that time.7

While research addressing the types and timing of emotional support delivered in HIV is sparse, the concepts identified in this research are described in literature from other disciplines. For example, Cutrona21 defines emotional support as expressions of comfort and caring (what we identify as connection), social integration or network support as membership in a group where members share common interests (what we define as identification), and esteem support as bolstering the sense of confidence or self-esteem (connection). She labels informational support as advice or guidance (similar to what we identify as navigation).

The matching hypothesis of social support specifies that the type of social support needed at a time of crisis should be matched to the specific type of stressor.21,22 However, in clinical settings that serve people newly diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, health-care providers may offer only cognitive support related to living with HIV/AIDS instead of emotional support that enables better processing of the diagnosis. This mismatch between social support and stressor may contribute to reasons why many people fail to return for HIV results or care – a situation that has been well documented in the literature.23–25 Providers have responded to the poor return rate by conveying as much information as possible to the person at the time of diagnosis. This information is usually focused on cognitive support (ie, why it is important to seek care and use condoms) and how to obtain tangible support (ie, eligibility for HIV-related services such as Ryan White).

In matching social support, variations in support needs are dependent on the nature of the stressor, and support offered should “match” the life domain in which a loss occurred.26 For example, an HIV diagnosis often leads to a disruption in someone’s social network and coping resources due to the stigmatizing nature of HIV. Therefore, the optimal support that may be needed at diagnosis would need to address that loss of social networks. Finally, Cutrona says measures of support are highly intercorrelated, which we found to be the case in our results in that participants often described more than one concept in linking to HIV care (ie, identification with someone who has HIV and empathy received from that individual). More research is needed to investigate optimal matching of support needs and linkage and engagement in HIV care.

Meeting the emotional support need of identification may be a challenge for providers who are not HIV positive or who do not disclose their HIV status. These providers can refer people newly diagnosed to HIV support groups or peer navigators to facilitate meeting emotional support needs. In addition, our findings suggest that providers can also help provide emotional support through physical touch (eg, holding someone’s hand) and by emphasizing their availability and long-term commitment to the patient.

Some participants identified peer navigation as an ideal way to deliver emotional support by connecting people newly diagnosed with HIV to others previously diagnosed. PLWH are able to understand the feelings at diagnosis and the process of linking to care since they shared the same experience at one point in their life (identification). For example, all participants talked about the crisis period when they received the diagnosis and were trying to assimilate it into the rest of their lives. A peer (with HIV) can help people newly diagnosed with HIV by describing that time to help them identify and deal with their feelings. Peers can help meet the emotional support needs for PLWH through identification, connection, and navigation. Funding for peer navigation programs is sparse, especially in rural areas. Recent literature about peer programs in HIV indicate mixed results due to varying types of program evaluations, but they promote engagement in care.27 More research is needed in this area.

Several limitations in this research should be mentioned. First, understanding emotional support was not an aim of the primary study; therefore, investigators may not have received salient information regarding emotional support from all the participants and this may have limited saturation. The sample was recruited from a small metropolitan and rural area, which has fewer health-care resources than larger, urban environments, and some in the sample were recruited from a center that recruits research participants. The sample also had a wide range of years since receiving an HIV diagnosis and those diagnosed many years ago may have had poorer recall and different experiences from those more recently diagnosed. Furthermore, the results are not generalizable to all PLWH but may be relevant to those who do not engage in care because of a lack of emotional support. Finally, we were not able to identify anyone who has never sought HIV care since diagnosis, and such persons could have enhanced understanding of the reasons for someone deciding not to engage in HIV care.

Conclusion

Providers often miss opportunities to respond empathically to patient’s emotions and instead address the medical problem(s) underlying the emotion.28 Patient-centered care emphasizes that patients desire care that seeks a holistic understanding of the patient’s needs, including their emotional needs.29 Failing to provide the appropriate type of social support during an HIV diagnosis disregards patients’ needs and may negatively impact on the quality of care.30 While more research needs to be performed, our findings suggest that providers and clinics should offer emotional support to people newly diagnosed with HIV and refer them to peers with HIV/AIDS to improve engagement in care.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Debra McDonald, editor, Office of Research and Scholarship, University of Florida College of Nursing. Publication of this article was funded in part by the University of Florida Open Access Publishing Fund.

Footnotes

Author contributions

CLC designed the primary study and this analysis, collected and analyzed data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. SC coded and analyzed data and was also a major contributor in writing the manuscript. NE provided content expertise and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. RLC provided content expertise and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Maddox L, Poschman K. HIV/AIDS Prevention Coordinators Meeting. Florida: Florida Department of Health; 2015. Cascade: The Continuum of HIV Care – Florida 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mugavero MJ, Norton WE, Saag MS. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 2):S238–S246. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Horn T, Thompson MA. The state of engagement in HIV care in the United States: from cascade to continuum to control. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(8):1164–1171. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lima VD, Johnston K, Hogg RS, et al. Expanded access to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a potentially powerful strategy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(1):59–67. doi: 10.1086/588673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White House Office of National AIDS Policy National HIV/AIDS Strategy for The United States: Updated to 2020– nhas-update.pdf. 2015. [Accessed October 16, 2015]. Available from: https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update.pdf.

- 6.Reif SS, Whetten K, Wilson ER, et al. HIV/AIDS in the Southern USA: a disproportionate epidemic. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):351–359. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.824535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson DE. Types and timing of social support. J Health Soc Behav. 1986;27(3):250–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH. Social Relationships and Health. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly JD, Hartman C, Graham J, Kallen MA, Giordano TP. Social support as a predictor of early diagnosis, linkage, retention, and adherence to HIV care: results from the Steps Study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(5):405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook CL, Lutz BJ, Young ME, Hall A, Stacciarini JM. Perspectives of linkage to care among people diagnosed with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015;26(2):110–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakenham KI. Specification of social support behaviours and network dimensions along the HIV continuum for gay men. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;34(2):147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray KM, Cohen SM, Hu X, Li J, Mermin J, Hall HI. Jurisdiction level differences in Hiv diagnosis, retention in care, and viral suppression in the United States. Jaids J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(2):129–132. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Struass A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schatzman L. Dimensional analysis: notes on an alternative approach to the grounding of theory in qualitative research. In: Maines DR, editor. Social Organization and Social Process. Vol. 1991. New York, NY: Aldine DeGruyter; pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray JB. Social support communication in unplanned pregnancy: support types, messages, sources, and timing. J Health Commun. 2014;19(10):1196–1211. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.872722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis JA, Lewis MD. Community Counseling. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sidell NL. Adult adjustment to chronic illness: a review of the literature. Health Soc Work. 1997;22(1):5–11. doi: 10.1093/hsw/22.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seekins D, Scibelli A, Juday T, Stryker R, Das A. Barriers to accessing HIV testing, care, and treatment in the United States; Presented at XVIII International AIDS Conference; Vienna, Austria: Jul 23, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutrona CE. Stress and social support-in search of optimal matching. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1990;9(1):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muñoz M, Bayona J, Sanchez E, et al. Matching social support to individual needs: a community-based intervention to improve HIV treatment adherence in a resource-poor setting. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1454–1464. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9697-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hightow LB, Miller WC, Leone PA, Wohl D, Smurzynski M, Kaplan AH. Failure to return for HIV posttest counseling in an STD clinic population. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(3):282–290. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.4.282.23826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinsler JJ, Cunningham WE, Davis C, Wong MD. Time trends in failure to return for HIV test results. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(6):397–400. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000249757.10209.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan PS, Lansky A, Drake A, HITS-2000 Investigators Failure to return for HIV test results among persons at high risk for HIV infection: results from a multistate interview project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(5):511–518. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thoits PA. Stress, Coping, and Social Support Processes: Where Are We? What Next? [Accessed August 16, 2015];J Health Soc Behav. 1995 35 (Extra Issue: Forty Years of Medical Sociology: The State of the Art and Directions for the Future) 53–79 Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2626957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutcher MV, Phicil SN, Goldenkranz SB, et al. “Positive examples”: a bottom-up approach to identifying best practices in HIV care and treatment based on the experiences of peer educators. AIDS Patient Care STDS”. 2011;25(7):403–411. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu I, Saha S, Korthuis PT, et al. Providing support to patients in emotional encounters: a new perspective on missed empathic opportunities. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(3):436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centered care. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):444–445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services What is Health Care Quality and Who Decides? [Accessed October 22, 2015]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/asl/testify/2009/03/t20090318b.html. Published 2013.