Abstract

Background: Sudden-onset severe obsessive-compulsive symptoms and/or severely restrictive food intake with at least two coinciding, similarly debilitating neuropsychiatric symptoms define Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS). When associated with Group A Streptococcus, the syndrome is labeled Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal infections (PANDAS). An abnormal immune response to infection and subsequent neuroinflammation is postulated to play an etiologic role. Most patients have a relapsing-remitting course. Treatment outcome data for youth with PANS and PANDAS are limited.

Methods: One hundred seventy-eight consecutive patients were seen in the Stanford PANS clinic between September 1, 2012 and January 15, 2016, of whom 98 met PANS or PANDAS criteria, had a single episode of PANS or relapsing/remitting course, and collectively experienced 403 flares. Eighty-five flares were treated with 102 total courses of oral corticosteroids of either short (4–5 days) or long (5 days–8 weeks) duration. Response to treatment was assessed within 14 days of initiating a short burst of corticosteroids and at the end of a long burst based on clinician documentation and patient questionnaires. Data were analyzed by using multilevel random-effects models.

Results: Patients experienced shorter flares when treated with oral corticosteroids (6.4 ± 5.0 weeks vs. 11.4 ± 8.6 weeks) than when not treated (p < 0.001), even after controlling for presumed confounding variables, including age at flare, weeks since onset of PANS illness, sex, antibiotic treatment, prophylactic antibiotics, previous immunomodulatory treatment, maintenance anti-inflammatory therapy, psychiatric medications, and cognitive behavioral therapy (p < 0.01). When corticosteroids were given for the initial PANS episode, flares tended to be shorter (10.3 ± 5.7 weeks) than when not treated (16.5 ± 9.6 weeks) (p = 0.06). This difference was statistically significant after controlling for the relevant confounding variables listed earlier (p < 0.01). Earlier use of corticosteroids was associated with shorter flare durations (p < 0.001). Longer courses of corticosteroids were associated with a more enduring impact on the duration of neuropsychiatric symptom improvement (p = 0.014).

Conclusion: Corticosteroids may be a helpful treatment intervention in patients with new-onset and relapsing/remitting PANS and PANDAS, hastening symptom improvement or resolution. When corticosteroids are given earlier in a disease flare, symptoms improve more quickly and patients achieve clinical remission sooner. Longer courses of corticosteroids may result in more durable remissions. A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of corticosteroids in PANS is warranted to formally assess treatment efficacy.

Keywords: : PANS, PANDAS, corticosteroids, obsessive-compulsive disorder, tics, immune modulation

Introduction

Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) is a syndrome that is characterized by the abrupt and dramatic onset of obsessive-compulsive (OC) symptoms and/or severely restrictive food intake with at least two coinciding, equally debilitating symptoms (anxiety, mood dysregulation, irritability/aggression/oppositionality, behavioral regression, cognitive deterioration, sensory or motor abnormalities, and somatic symptoms) (Swedo et al. 2012; Chang et al. 2015). When the onset of flares is associated with Group A Streptococcus (GAS), the disorder is labeled Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal infections (PANDAS), a syndrome that is characterized by acute-onset OC symptoms and/or tics along with the neuropsychiatric symptoms mentioned earlier (Swedo et al. 1998). The symptoms of PANS and PANDAS relapse and remit over time. During relapses, or “flares” (abrupt neuropsychiatric deteriorations), children may become severely ill and incapacitated for weeks to months; during remission, they may return to their pre-episode baseline function or have residual symptoms. In some cases, flares may resolve without intervention, but since flares likely reflect active brain inflammation (Williams and Swedo 2015; Cutforth et al. 2016), anti-inflammatory therapy may logically minimize flare duration and reduce symptoms and residual symptoms. Its use has precedence in other inflammatory brain diseases (Duzova and Bakkaloglu 2008; Armangue et al. 2012; Bale 2015; Nosadini et al. 2015; Magro-Checa et al. 2016).

Symptoms of PANS and PANDAS are hypothesized to result from immune dysfunction at multiple levels: local (targeted) dysfunction related to cross-reactive antibodies that recognize specific central nervous system (CNS) antigens; regional dysfunction related to inflammation within neuronal tissues in the basal ganglia and possibly vasculature of the basal ganglia; and systemic abnormalities of cytokines or chemokines, with resultant disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and CNS functions (Cutforth et al. 2016; Orefici et al. 2016). This hypothesis is based on disease mechanisms demonstrated in animal models (Hoffman et al. 2004; Yaddanapudi et al. 2010; Brimberg et al. 2012; Cox et al. 2013; Lotan et al. 2014; Cutforth et al. 2016; Dileepan et al. 2016) and is proposed for and widely substantiated in Sydenham's chorea (SC), a disease that shares many features with PANS and PANDAS (Williams and Swedo 2015). Psychiatric symptoms, including OC symptoms, are common in patients with SC (Swedo et al. 1989, 1993; Asbahr et al. 1998, 1999; Maia et al. 2005). Immunomodulatory therapies for SC demonstrate not only benefits for the choreoathetoid movements but also OC symptoms (Swedo 1994) and emotional instability (Barash et al. 2005; Garvey et al. 2005; Walker et al. 2005, 2007), thus justifying trials of such therapies in PANS and PANDAS.

PANS and PANDAS are disabling conditions that seriously threaten a child's well-being and family functioning; for example, these children suffer from extreme obsessions, compulsions, anxiety, tics, behavior regression, aggression, psychosis, and mood instability (Swedo et al. 1998; Frankovich et al. 2015a, 2015b; Murphy et al. 2015). Caregiver burden scores are extremely high (Frankovich et al. 2015a), even higher than those reported in caregivers of Alzheimer's patients who qualify for respite care (Novak and Guest 1989). Consequently, effective therapies could alleviate considerable suffering and distress. However, determination of the optimal treatment for this disorder is challenging for three reasons: (1) The symptoms may be a common manifestation of clinically heterogeneous diseases that are triggered by different agents; (2) the disease affects multiple neurological and psychiatric domains; and (3) PANS has diverse trajectories (Frankovich et al. 2017).

Although the evidence discussed earlier provides a rationale for its use, no studies have systematically evaluated the effects of corticosteroid therapy in PANS or PANDAS. Evidence does support the efficacy of corticosteroids in SC (Garvey et al. 2005; Paz et al. 2006). In patients with SC, a randomized double-blind study found that a prolonged course of prednisone significantly reduced chorea intensity and illness duration (Paz et al. 2006). Observational studies suggest that corticosteroids have a positive effect on both chorea and emotional instability in SC (Barash et al. 2005; Garvey et al. 2005; Walker et al. 2005, 2007). In addition, two case studies reported neuropsychiatric improvement with corticosteroids in patients meeting criteria for PANS (Allen et al. 1995; Frankovich et al. 2015b). These studies, compounded with the similarities between PANS, PANDAS, and SC in terms of symptom and antibody profiles, further justify the use of corticosteroids in PANS.

The Stanford PANS Program, created to research the etiology of and treatment for this disorder, conducts a community based interdisciplinary clinic designed to evaluate and treat youth with suspected PANS or PANDAS. Our program accepts patients who live locally (83% live within 90 miles). For our local cohort we require frequent follow-up visits (every 1–2 weeks during flare and every 4–12 weeks during remissions).

We designed this retrospective case review with the following three aims (developed a priori): (1) to assess the impact of oral corticosteroid use on duration of PANS flares in patients with new-onset PANS and in patients with relapsing/remitting illness (primary analysis); (2) to evaluate the impact of timing of corticosteroid introduction on flare duration; and (3) to evaluate the effect of corticosteroid course length on duration of neuropsychiatric symptom improvement. In addition, we investigated the side effects of oral corticosteroid use and the impact of documented acute illnesses and illness exposure on corticosteroid response.

Methods

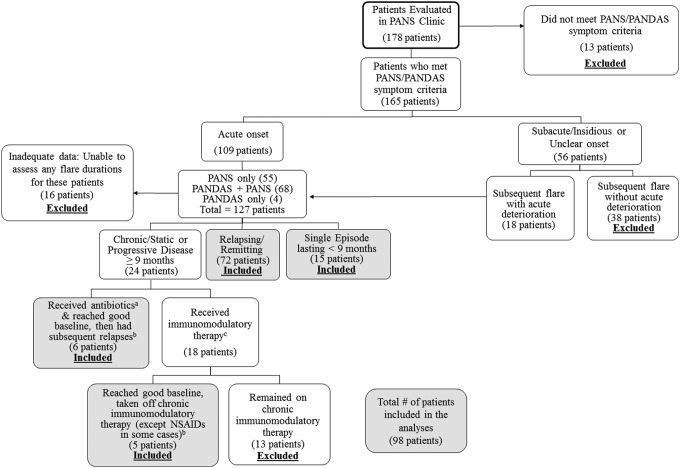

We reviewed clinical electronic medical records (EMR) of 178 consecutive patients seen in the Stanford PANS clinic between September 1, 2012 and January 15, 2016 (Fig. 1) or by our PANS psychiatrist (M.T.) before starting the formal multi-disciplinary clinic. A retrospective review of patient medical records and prospective data collection were approved by the Stanford Panel on Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

FIG. 1.

Patients evaluated at the Stanford PANS clinic included in the analyses. aAntibiotics given for infection. bIn this group of patients, only subsequent relapses were included in the analyses. cIntravenous immunoglobulins, high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulsing (30 mg/kg), plasmapheresis, mycophenylate mofetil, rituximab, etc. NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PANS, Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome.

Definitions of relapsing/remitting, chronic-static, and progressive

“Relapsing/remitting” course was defined as having disease relapses followed by an approximate return to 90%–95% of preflare baseline without the need for aggressive immunomodulatory therapy (see Patient Exclusion Criteria section below). “Chronic-static” course was defined as having persistent PANS symptoms lasting longer than 9 months. “Progressive disease” was defined as having deteriorating neurobehavioral or cognitive function over at least a 9-month period.

Patient inclusion criteria

Patients were included in the analysis if they had an initial or subsequent acute clinical deterioration that strictly met research criteria for PANS or PANDAS (Swedo et al. 1998; Swedo et al. 2012; Chang et al. 2015) and had either a single episode (not meeting criteria for chronic-static or progressive) or a relapsing/remitting course (Fig. 1).

Patient exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they received aggressive disease-modifying therapies such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, or mycophenylate mofetil and/or required chronic immunomodulatory therapy to sustain a good baseline (i.e., monthly intravenous immunoglobulins [IVIG] and/or monthly intravenous [IV] methylprednisolone pulses). Patients were excluded if there was inadequate documentation to assess the duration of at least one flare.

“Rescued” flares

The term “rescued flare” refers to flares that were treated with IVIG, high-dose IV methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg), or plasmapheresis. “Rescued flares” were excluded from the primary analysis, as these flares were felt to be significantly different from flares that were not “rescued.” A total of 54 flares were “rescued”: 28 were treated with corticosteroids, and 26 were not treated. Due to concern that there is a higher proportion of “rescued flares” in the corticosteroid-treated group compared with the not-treated group, we did a sensitivity analysis to include these “rescued flares” for both groups.

Incompletely resolved flares

Flares that were unresolved before subsequent deterioration were excluded from the primary analyses (Tables 3, 4 and 5A). A total of 13 flares were unresolved before subsequent deterioration: Four were treated with steroids, and nine were not treated. The four incompletely resolved flares treated with corticosteroids were included in secondary analyses (Tables 5B and 6). Due to concern of excluding flares that were not completely resolved before subsequent deterioration would bias our results, we did a sensitivity analysis that included these flare durations such that we set the end date of the flare as the day before the subsequent deterioration.

Table 3.

Corticosteroid Effect on Flare Duration Among Patients Who Had a Single Episode of PANS or Relapsing/Remitting PANS

| Unadjusted model | Model adjusted for demographic/disease variables | Final model, adjusted for demographic/disease and treatment variables | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ba (95% CI) | Ba (95% CI) | Ba (95% CI) | |

| DV: flare duration (weeks) | |||

| Oral corticosteroid course | −4.72*** (−7.23 to −2.21) | −4.46*** (−6.94 to 1.99) | −3.50** (−5.95 to 1.05) |

| Age at onset of PANS illness (years) | 0.40* (0.01 to 0.79) | −0.16 (−0.54 to 0.22) | |

| Sex | −0.35 (−3.08 to 2.39) | −0.85 (−3.30 to 1.60) | |

| Weeks since onset of PANS illness | −0.02** (−0.02 to −0.01) | −0.01* (−0.02 to 0) | |

| Previous flare treated with aggressive therapyb | −4.13* (−7.82 to −0.44) | −4.20* (−7.57 to −0.83) | |

| Antibiotics given to treat infection during flarec | 2.26* (0.38 to 4.14) | ||

| Prophylactic antibiotics | −0.58 (−3.01 to 1.84) | ||

| Maintenance anti-inflammatory therapyd | −0.62 (−2.69 to 1.45) | ||

| Number of psychiatric medications during flare | 1.88*** (1.15 to 2.60) | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy during flare | 4.28*** (1.92 to 6.64) | ||

Multilevel model reflecting effect of corticosteroid treatment on length of flares nested within individuals, adjusting for the listed covariates.

p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

The unstandardized beta coefficient is interpreted as the expected change in the dependent variable with 1 U change in the independent variable (e.g., in the final model, treatment with corticosteroids was associated with a 3.50-week decrease in flare duration).

Intravenous immunoglobulins, high dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulsing (30 mg/kg), or plasmapheresis.

Common infections treated during flare include Group A Streptococcus, sinusitis, otitis media, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, etc.

NSAIDs or prednisone maintenance (5–7.5 mg) given for at least 10 days during assessed flare.

B, unstandardized beta; CI, confidence interval; DV, dependent variable; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PANS, Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome.

Table 4.

Corticosteroid Effect on Duration of the Initial Presentation (i.e., First PANS Flare) of PANS

| Unadjusted model | Model adjusted for demographic/disease variables | Final model, adjusted for demographic/disease and treatment variables | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ba (95% CI) | Ba (95% CI) | Ba (95% CI) | |

| DV: flare duration (weeks) | |||

| Oral corticosteroid course | −6.11 (−12.5 to 0.27) | −6.70* (−13.0 to −0.42) | −7.49** (−13.0 to −1.95) |

| Age at onset of PANS | 0.62 (−0.14 to 1.37) | −0.33 (−1.13 to 0.48) | |

| Sex | 0.49 (−4.38 to 5.37) | −1.33 (−5.90 to 3.24) | |

| Antibiotics given to treat infection during flareb | 0.56 (−4.69 to 5.82) | ||

| Maintenance anti-inflammatory therapyc | 3.74 (−2.05 to 9.53) | ||

| Number of psychiatric medications during flare | 2.20*** (0.90 to 3.50) | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy during flare | 5.23* (0.02 to 10.4) | ||

Multilevel model reflecting effect of corticosteroid treatment on length of flares nested within individuals, adjusting for the listed covariates.

p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

The unstandardized beta coefficient is interpreted as the expected change in the dependent variable with 1 U change in the independent variable (e.g., in the final model, treatment with corticosteroids for the initial PANS flare was associated with a 7.49-week decrease in flare duration).

Common infections treated during flare include Group A Streptococcus, sinusitis, otitis media, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, etc.

NSAIDs or prednisone maintenance (5–7.5 mg daily) given for at least 10 days during flare.

B, unstandardized beta; CI, confidence interval; DV = dependent variable; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PANS, Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome.

Table 5.

(A) Effect of Timing of Corticosteroids on Flare Duration (B) Effect of Length of Corticosteroid Treatment on Duration of Improvement

| Unadjusted model | Model adjusted for demographic/disease variables | Final model, adjusted for demographic/disease and treatment variables | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ba (95% CI) | Ba (95% CI) | Ba (95% CI) | |

| (A) DV: flare duration (weeks) | |||

| Timing of oral corticosteroidb | 0.17*** (0.12 to 0.22) | 0.18*** (0.14 to 0.23) | 0.18*** (0.13 to 0.22) |

| Age at onset of PANS flare | 0.12 (−0.16 to 0.4) | 0.06 (−0.29 to 0.41) | |

| Sex | −0.64 (−2.59 to 1.31) | −0.77 (−2.72 to 1.18) | |

| Weeks since onset of PANS illness | 0 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0 (−0.01 to 0.01) | |

| Previous flare treated with aggressive therapyc | −0.76 (−3.31 to 1.8) | −0.68 (−3.28 to 1.91) | |

| Antibiotics given to treat infection during flared | −0.27 (−2.12 to 1.58) | ||

| Prophylactic antibiotics | −0.72 (−2.73 to 1.28) | ||

| Maintenance anti-inflammatory therapye | 1.59 (−0.31 to 3.48) | ||

| Number of psychiatric medications during flare | 0.36 (−0.43 to 1.16) | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy during flare | −0.33 (−2.71 to 2.05) | ||

| (B) DV: duration of improvement (days) | |||

| Length of oral corticosteroid treatment | 2.42* (0.33 to 4.51) | 2.44* (0.19 to 4.68) | 2.56* (0.51 to 4.62) |

| Age at onset of PANS flare | −1.51 (−7.09 to 4.08) | −0.33 (−6.79 to 6.13) | |

| Sex | −2.99 (−40.3 to 34.3) | −8.17 (−44.4 to 28.1) | |

| Weeks since onset of PANS illness | 0.07 (−0.14 to 0.27) | 0.05 (−0.15 to 0.24) | |

| Previous flare treated with aggressive therapyc | −26.1 (−76.3 to 24.1) | −34.4 (−81.4 to 12.7) | |

| Antibiotics given to treat infection during flared | 2.27 (−29.2 to 33.8) | ||

| Prophylactic antibiotics | 17.04 (−17.5 to 51.6) | ||

| Maintenance anti-inflammatory therapye | −23.2 (−56.7 to 10.4) | ||

| Number of psychiatric medications during flare | −8.24 (−18.2 to 1.8) | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy during flare | 13.7 (−29.6 to 57.1) | ||

Multilevel model reflecting effect of corticosteroid treatment on length of flares nested within individuals, adjusting for the listed covariates.

p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

The unstandardized beta coefficient is interpreted as the expected change in the dependent variable with 1 U change in the independent variable (e.g., in the final model, (A) each day that the corticosteroid is delayed is associated with a 0.18-week increase in flare duration. (B) Each additional day of corticosteroid treatment is associated with a 2.56-day increase in duration of improvement).

Timing of corticosteroids relative to onset of flare.

Intravenous immunoglobulins, high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulsing (30 mg/kg), or plasmapheresis.

Common infections treated during flare include Group A Streptococcus, sinusitis, otitis media, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, etc.

NSAIDs or prednisone maintenance (5–7.5 mg daily) given for at least 10 days during flare.

B, unstandardized beta; CI, confidence interval; DV, dependent variable; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PANS, Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome.

Table 6.

Effect of Overt Illness or Exposure to Housemate with Illness Due to Infection on Corticosteroid Response

| Overt illness or exposure to infection, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Response, n | Missing data | No | Yes |

| Missing data | 3 (43%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| No response | 1 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 11 (34%) |

| Partial response | 3 (43%) | 18 (58%) | 14 (44%) |

| Complete response | 0 | 12 (39%) | 6 (19%) |

A total of 85 flares were treated with corticosteroids, but 15 flares received more than one course of corticosteroids and were excluded from the earlier analysis. Table does not account for clustering of flares within individuals: Exposure/no response contains only one flare per subject. No exposure/partial response contains two subjects with two flares each and one subject with three flares. The remaining cells each contain two flares for one subject. The small cell size prevented use of the multilevel model, as evident in Tables 3, 4, and 5. Association between exposure and response, not accounting for clustering and excluding observations with missing data (n = 63 flares included in analysis), was statistically significant (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.004): Flares with an exposure were more likely to be in the “no response” category.

Missing flare duration data

Flares were still included even if the flare duration was missing. The missing X-side data were accommodated for by using multiple imputation routines in Mplus software (see Statistical Analyses section). Due to concern that missing flares would bias our results, we did a sensitivity analysis excluding patients (from both groups) who had more than one flare missing a start and/or end date.

Other excluded flares

Flares occurring <50 days after patients' initial treatment with IVIG, high-dose IV methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg), or plasmapheresis were excluded since the effects of these treatments were still in play. This time-frame was chosen, because the half-life of immunoglobulin G levels in healthy patients is 3–4 weeks, but it is longer for other disorders (Silvergleid and Ballow 2016). Patients were typically given plasmapheresis in conjunction with IVIG and/or IV methylprednisolone. For both IV methylprednisolone and IVIG, our experience is that most patients experience a recrudescence ∼3–4 weeks (average 25 days) after these therapies, but some patients maintain improvement longer. We chose to double the average half-life (50 days) of IVIG treatment to ensure that the increase in psychiatric symptoms was not due to the waning effects of IVIG or IV methylprednisolone. Patients treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or prednisone maintenance (5–7.5 mg daily) were included; we controlled for these variables in our multilevel model.

Definition of flares and flare resolution

Flare occurrence and flare duration were determined by clinical assessments (documented in the EMR), PANS Questionnaires and the PANS Global Impairment Scale (parent report), and documented communications between parents and providers (follow-up emails and phone calls). The PANS Global Impairment Scale was developed by Dr. James Leckman and his colleagues at Yale and the National Institute of Mental Health (personal communication). A flare was considered resolved when the child was functioning at or near their preflare baseline (as documented by the clinician in the EMR). All flare data that were recorded in medical and psychiatric records from all patients seen consecutively in our PANS clinic between September 1, 2012 and January 15, 2016 were included in the primary analyses (Tables 3, 4, and 5A), except for “rescued flares” and incompletely resolved flares. Any flare that started before January 15, 2016 was included and followed until the flare was resolved or the end of our data collection (September 1, 2016).

Oral corticosteroid treatment protocol

Patients presenting to clinic in a flare were first evaluated and treated for any underlying infection according to the PANS Research Consortium consensus statements on the evaluation and treatment of infections (Chang et al. 2015; Cooperstock et al. 2017). Before January 2015, our clinicians did not routinely use oral corticosteroids to treat new-onset PANS or PANS relapses due to concern for escalating psychiatric symptoms. After January 2015, the clinicians began offering oral corticosteroids more routinely to treat new-onset or relapses of PANS. Once infections were ruled out, remitted without treatment, or treated, parents were given the option of having the PANS flare treated with corticosteroids. When the presumed infectious trigger was sinusitis, patients were simultaneously started on antibiotics and corticosteroids, as both interventions have been shown to be effective in treating sinusitis (Rudmik and Soler 2015).

More caution was used by the clinicians in prescribing corticosteroids to patients with significant mood instability, psychotic symptoms, rage, aggression, and/or impulsivity or a history of previous adverse reaction to corticosteroids. In these cases, clinicians developed a clear, solid plan and contract to ensure patient and family safety. When the family did not have the ability or capacity to manage potential escalation in symptoms, clinicians selected alternative interventions (NSAIDs, supportive therapies, etc.). When steroids were given, contingency plans were made for additional supportive therapy and personnel. We disclosed to all families that we had limited data on the efficacy and safety of steroids in PANS. Many families chose not to give steroids based on this disclosure. Dosing offered was 1–2 mg/kg for 5 days (max dose 60 mg twice daily) and was sometimes followed by a prolonged taper. If oral corticosteroids were used but failed as solo therapy, the “rescue” therapy replaced the steroids (n = 26) or was added to the steroids (n = 28).

Definitions of response to corticosteroids and duration of improvement

Response was assessed within 14 days of initiating corticosteroids for a short burst (≤5 days) and at the end of treatment for a long burst (>5 days). Complete response (CR) was defined as the resolution of OC symptoms and/or eating restriction (PANS Criterion I), with definitive improvement in Criterion II neuropsychiatric symptoms and patient functioning at or near 95% of preflare baseline (Swedo et al. 2012). Partial response (PR) was defined as the decreased severity of PANS symptoms, but with overall functioning remaining impaired per clinician notes and parent questionnaire data. The start date for “duration of improvement” was defined as the day the patient achieved CR or PR to the time of clear psychiatric deterioration.

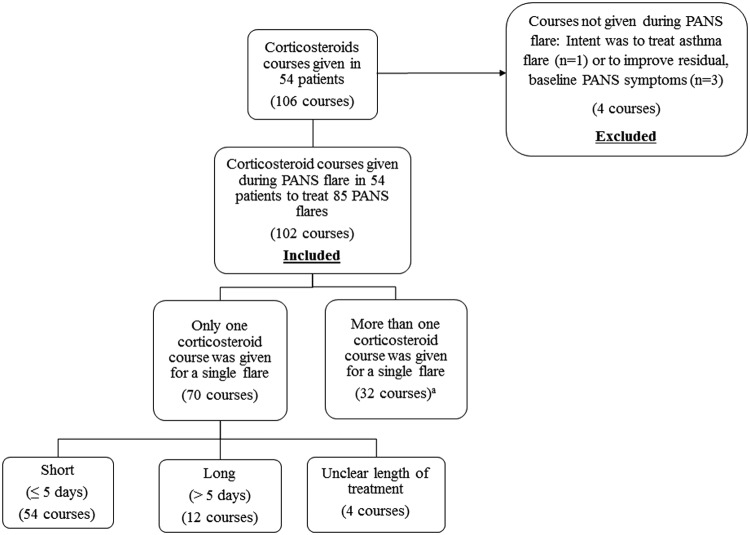

Corticosteroid courses are reported in Figure 2. Courses were included even if corticosteroids were discontinued prematurely due to side effects (n = 3) and if corticosteroids were prescribed to treat croup and the patient was in a PANS flare (n = 2). Corticosteroid courses were excluded when used to treat asthma and the patient was not in a PANS flare (n = 1) and when used to treat residual baseline PANS symptoms (n = 3).

FIG. 2.

Corticosteroid courses in patients (n = 54) who had a single episode of PANS or relapsing/remitting PANS included in the analyses. aMultiple corticosteroid courses given for a single flare were excluded from Tables 5A, B, and 6 analyses. PANS, Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome.

Side effects

Neuropsychiatric side effects of corticosteroids were differentiated from the patient's underlying symptoms when there was a clear increase in psychiatric symptoms temporally associated with corticosteroid treatment and a return to a previous or improved level of severity shortly after discontinuation.

Statistical analyses

We used a multilevel random-effects model to account for within-individual correlation, adjusting for 10 covariates in all models (sex, age at flare onset, weeks since onset of PANS illness, antibiotic treatment during flare, prophylactic antibiotics before flare, previous treatment with immunomodulation [IVIG, IV methylprednisolone, or plasmapheresis], NSAIDs/prednisone maintenance, number of psychiatric medications, and cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT] during flare). The initial flare (i.e., first recognized PANS flare) was only controlled for relevant covariates (sex, age at flare onset, antibiotic treatment during flare, NSAIDs/prednisone maintenance, psychiatric medications, and CBT during flare). Given that maximum likelihood estimation cannot be relied on to accommodate missing X-side data, multiple imputation routines in Mplus software (Muthén and Muthén 2012) were used to generate pooled results across 20 datasets, accounting for the multilevel structure of the data and the distribution of the variables. A Fisher's exact test was used to assess the effect of overt illness or illness exposure on response, since small cell sizes prevented the use of the multilevel model. All other analyses were carried out in R 3.2.2 (R Core Team 2013). Companion analyses with complete-case data were performed to ensure comparability across results (available on request). We report unstandardized beta coefficients with 95% confidence intervals, which are interpreted as the change in the dependent variable with each 1-U change in the independent variable. Alpha was set to 0.05.

Results

Ninety-eight patients met inclusion criteria for this study (Fig. 1). Patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. Patients treated with corticosteroids had a higher PANS Global Impairment Score (51.8 ± 28.2) at presentation to clinic than patients never treated with corticosteroids (40.3 ± 25.2) (p = 0.04).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics in 98 Patients Who Had a Single Episode of PANS or Relapsing/Remitting PANS

| Never had oral corticosteroids | Corticosteroidsa | Comparisonb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 44 | 54 | n/a |

| Males | 25/44 (57%) | 36/54 (67%) | p = 0.43 |

| Number of flares | 3.8 ± 3.3 | 4.3 ± 3.4 | p = 0.47 |

| Age at onset of PANS illness (years) | 7.8 ± 3.8 | 8.6 ± 3.2 | p = 0.25 |

| PANS Global Impairment Scorec | 40.3 ± 25.2 | 51.8 ± 28.2 | p = 0.04 |

| Caregiver Burden Inventoryc | 34.4 ± 23.5 | 37.1 ± 19.9 | p = 0.57 |

| Obsessive-compulsive symptoms | 40/44 (91%) | 49/54 (91%) | p = 0.99 |

| Eating restrictiond | 24/43 (56%) | 25/54 (46%) | p = 0.47 |

| Anxiety | 42/44 (95%) | 54/54 (100%) | p = 0.39 |

| Mood disordere | 42/44 (95%) | 54/54 (100%) | p = 0.39 |

| Irritability/oppositionality/aggression | 42/44 (95%) | 51/54 (94%) | p = 0.99 |

| Behavior regressiond | 33/44 (75%) | 43/53 (81%) | p = 0.63 |

| Deterioration in schoold | 30/43 (70%) | 40/52 (77%) | p = 0.58 |

| Sensory or motor symptomsd | 40/44 (91%) | 52/53 (98%) | p = 0.26 |

| Somatic symptomsd | 41/43 (95%) | 53/54 (98%) | p = 0.84 |

Patients who received at least one course of oral corticosteroids.

Difference in means assessed using the t-test. Difference in proportions assessed using the chi-square test.

PANS Global Impairment Score and Caregiver Burden Inventory collected at the initial presentation to the Stanford PANS clinic.

Data are missing for some neuropsychiatric symptoms; this is reflected in the denominators of the categorical variables.

Mood disorder, including depression and/or emotional lability.

PANS, Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome.

Flare Characteristics

Flare characteristics are reported in Table 2. The mean number of flares per individual for corticosteroid treated flares was 0.9 ± 1.2 and 3.3 ± 3.1 for noncorticosteroid treated flares. Thirteen flares treated with corticosteroids received more than one course of corticosteroids, and these flares were included in the flare duration analyses (Tables 3 and 4). We included those 13 flares to ensure that we did not bias the results by excluding the most severe flares, since more severe and longstanding flares are more likely to receive multiple courses of steroids. However, these 13 flares that received 28 total corticosteroid courses were excluded from Tables 5A, 5B, and 6 analyses, since flares treated with multiple corticosteroid courses were considered to be incomparable to flares treated with a single corticosteroid course in regards to the effect of timing of corticosteroid introduction on flare duration, time to improvement, duration of improvement, and treatment response.

Table 2.

Flare Characteristics in 98 Patients Who Had a Single Episode of PANS or Relapsing/Remitting PANS

| Flare not treated with corticosteroids | Flare treated with oral corticosteroids | Comparisona | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of flares | 318 | 85 | n/a |

| Mean age at onset of PANS flare (years) | 9.8 ± 3.9 | 10.5 ± 3.5 | p = 0.10 |

| Mean weeks since onset of PANS illness | 131.2 ± 149.4 | 111.0 ± 105.0 | p = 0.25 |

| Previous flare treated with aggressiveb therapy | 49/318 (15%) | 22/85 (26%) | p = 0.04 |

| Antibiotics given to treat infectionc during flared | 173/271 (64%) | 53/85 (62%) | p = 0.91 |

| Prophylactic antibioticsd | 81/294 (28%) | 46/84 (55%) | p < 0.001 |

| Maintenance anti-inflammatorye therapyd | 101/316 (32%) | 36/85 (42%) | p < 0.001 |

| Mean No. of psychiatric medications during flare | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | p = 0.048 |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy during flared | 73/287 (25%) | 23/83 (28%) | p = 0.78 |

Difference in means assessed using the t-test. Difference in proportions assessed using the chi-square test.

Intravenous immunoglobulins, high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulsing (30 mg/kg), or plasmapheresis.

Common infections treated during flare include Group A Streptococcus, sinusitis, otitis media, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, etc.

Data are missing for some flares; this is reflected in the denominators of the categorical variables.

NSAIDs or prednisone maintenance (5–7.5 mg daily) given for at least 10 days during flare.

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PANS, Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome.

Number and Duration of Corticosteroid Treatments

A total of 102 courses of oral corticosteroids were given to 54 patients for 85 PANS flares (Fig. 2). Twenty-six flares treated with a single corticosteroid course had incomplete responses and were eventually “rescued.” These 26 corticosteroid courses were included in Tables 5B and 6 analyses, since the duration of improvement and response to corticosteroids data were collected before initiation of IVIG, IV methylprednisolone, or plasmapheresis. A short course of corticosteroids was given for new-onset or mild-to-moderate flares. Prolonged (>5 days) courses of corticosteroids were generally given in the following settings: patients with new-onset PANS (n = 4), patients with early relapse occurring within 1 month of a previous flare (n = 6), or patients with long-standing PANS symptoms (n = 4).

Impact of Oral Corticosteroids on Flare Duration

Flares treated with corticosteroids were shorter (6.4 ± 5.0 weeks) than flares not treated with corticosteroids (11.4 ± 8.6 weeks) (p < 0.001). This difference remained significant after accounting for all covariates (p < 0.01) (Table 3). The three sensitivity analyses we conducted to rule out biases did not significantly alter the primary results reported in Table 3 (sensitivity analyses available on request). When corticosteroids were initiated early in disease flare, patients experienced shorter flares (multilevel model, p < 0.001).

Initial Onset of PANS

Nine patients treated and 56 patients not treated with corticosteroid bursts for the initial PANS flare were included in Table 4. Shorter flare duration was observed when corticosteroids were given for the initial PANS episode (10.3 ± 5.7 weeks) than when not treated (16.5 ± 9.6 weeks) (p = 0.06). This difference became statistically significant after controlling for age, sex, antibiotics, NSAIDs/prednisone maintenance, psychiatric medications, and CBT during flare (p < 0.01) (Table 4).

Time to Response and Duration of Improvement

Improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms began, on average, 3.6 ± 3.1 days after starting the burst. Improvement lasted an average of 43.9 ± 56.6 days before the next flare or symptom escalation. Earlier time to steroid introduction was associated with faster time to flare resolution (p < 0.001) (Table 5A). Longer courses of corticosteroids were associated with a more enduring impact on the duration of neuropsychiatric symptom improvement (p = 0.01) (Table 5B).

Response Rate

Most corticosteroid courses were associated with a positive clinical response. Sixty-seven of the 70 corticosteroid courses had enough documentation to assess response to corticosteroids. Fifty-three (79%) courses were associated with improvement, with 18 (27%) having a CR and 35 (52%) a PR. Having an overt illness or exposure to housemate with infection within the 14 days after initiation of corticosteroids was associated with no response, without accounting for clustering (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.004) (Table 6).

Side Effects of Corticosteroids

Temporary side effects were reported during 45 out of 102 (44%) courses of oral corticosteroids given for a PANS flare. The most commonly reported side effects were escalation of neuropsychiatric symptoms, including: increase in OC symptoms (n = 10), anxiety (n = 16), emotional lability/moodiness (n = 12), irritability/agitation (n = 15), sleep disturbance (n = 10), tics (n = 7), aggression/anger/rage (n = 4), urinary symptoms (n = 5), mania (n = 3), sensory amplification (n = 3), hyperactivity (n = 2), hallucinations (n = 2), vision abnormalities (n = 2), behavior regression (n = 2), and flat affect (n = 1). These side effects often reflected a mild increase in neuropsychiatric symptoms that were short-lived and resolved soon after discontinuation of corticosteroids. However, in three patients, escalation in neuropsychiatric symptoms were so severe that the steroid course was aborted early. Of the 15 patients who received a prolonged course (>5 days) of corticosteroids or multiple courses (≥3) within 1 month, eight (53%) had either weight gain and/or Cushingoid features: weight gain only (n = 2), Cushingoid only (n = 2), both (n = 4). No patients showed signs or symptoms of cataracts, bone infarcts, or diabetes after the corticosteroid intervention.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the impact of oral corticosteroids on the treatment of psychiatric symptoms in patients who meet research criteria for PANS and/or PANDAS. The observations of this retrospective case review study resemble those seen in SC cohorts (Barash et al. 2005; Paz et al. 2006; Walker et al. 2007).

Approximately one-fifth of the flares seen over the time period of the study were treated with oral corticosteroids. Flares treated with corticosteroids appear to resolve more quickly than flares not treated with corticosteroids (6.4 ± 5.0 weeks treated vs. 11.4 ± 8.6 weeks not treated [p < 0.001]), and this held true after controlling for covariates (p < 0.01) (Table 3). Improvement was more robust when corticosteroids were given earlier in disease flare (Table 5A). Longer courses of corticosteroids had a more enduring impact on neuropsychiatric symptom improvement (Table 5B). Although patients who received corticosteroids were more severe in terms of the PANS Global Impairment Scale (Table 1), these individuals still experienced shorter flares when treated with corticosteroids. Although psychiatric medications and CBT were associated with longer flares, we believe that this may reflect a higher severity of impairment in the flare, making them more likely to receive additional psychiatric interventions. Side effects of the corticosteroid treatment in this setting were primarily psychiatric and self-limited. However, patients on prolonged corticosteroids (>5 days) or multiple courses within 1 month often gained weight and/or developed Cushingoid features.

We suspect that the improvement of PANS symptoms is due to the immunosuppressive effects of corticosteroids, but the exact mechanisms are unknown. Animal and human research suggests that autoimmune mechanisms and microglial activation likely play a role in poststreptococcal neuropsychiatric diseases (Kumar et al. 2015; Macri et al. 2015; Williams and Swedo 2015; Carapetis et al. 2016; Cutforth et al. 2016; Dileepan et al. 2016). Animal models of SC and PANDAS point to an essential role of the adaptive immune response (cellular and humoral) in disease pathogenesis, including Th17 cells and autoantibodies, which is consistent with the molecular mimicry hypothesis (Hoffman et al. 2004; Yaddanapudi et al. 2010; Brimberg et al. 2012; Cox et al. 2013; Lotan et al. 2014; Carapetis et al. 2016; Cutforth et al. 2016; Orefici et al. 2016). It has recently been shown that multiple intranasal infections with live GAS in mice generate GAS-specific Th17 cells that gain access to the brain by migrating along olfactory sensory axons. The migration of Th17 cells into the brain is associated with neurovascular damage, including BBB breakdown, neuroinflammation, and loss of excitatory synaptic proteins that are essential for neurotransmission (Dileepan et al. 2016). In addition, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging studies of patients with PANDAS suggest that they have a higher degree of microglial activation compared with controls (Kumar et al. 2015). Corticosteroids can reduce the effects of all these inflammatory pathways, including reduction of the Th17 response (Muls et al. 2012), BBB permeability (Forster et al. 2008), and microglial activation (Hinkerohe et al. 2010).

Corticosteroids are used in other relapsing/remitting diseases, including multiple sclerosis, asthma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and arthritis. In these diseases, bursts of corticosteroids used in the absence of maintenance therapy often fail to achieve and maintain remission. As in these other diseases, more aggressive induction regimens and/or maintenance immunomodulatory therapy may be necessary to achieve durable remissions in patients with PANS. Administration of corticosteroids in the context of infection carries risks of reducing immune function that are necessary for pathogen detection and eradication and perhaps predisposes the patient to future autoimmune events.

Limitations

As with all retrospective studies, documentation was imperfect. Our documentation regarding exact dates of flares and resolution has improved with the growth of our multi-disciplinary clinic. Many earlier flares did not have a clearly documented start and end date, and these missing flare durations were accommodated for by using multiple imputation routines in Mplus software, which may have biased our results. Some patients did not follow up with our clinic regularly or had flares between clinic visits that were not properly documented, thus contributing to inadequate documentation. However, most clinically significant flares resulted in clinic visits, since the majority of our patients (83%) live within 90 miles of the clinic.

We conducted three sensitivity analyses to evaluate bias due to excluded, missing, and incompletely resolved flares. Due to concern that a higher proportion of flares in the corticosteroid treated group were “rescued” with immunomodulatory therapy (IVIG, high-dose IV methylprednisolone pulsing, and/or plasmapheresis) compared with the untreated group, we performed a sensitivity analysis including these flares. Due to concern that patients with multiple missing flares would bias our results, we performed a sensitivity analysis to exclude patients who had more than one flare with missing start and/or end date. Due to concern over excluding flares that were not completely resolved before subsequent deterioration would bias our results, we performed a sensitivity analysis to include these flare durations in which we set the end date of the flare as the day before subsequent deterioration. Our final results from the primary analysis (Table 3) were not significantly altered by any of these sensitivity analyses. Sensitivity analyses are available on request.

Other limitations include the absence of reliable and valid psychiatric assessment instruments in our clinical assessments, as there is no single measure that adequately reports impairment in all of the psychiatric symptom categories that are affected in PANS and PANDAS and the PANS Impairment Score has not been validated. Therefore, our primary analysis focused on flare duration and durability of improvement, which is the same approach used in reporting corticosteroid impact in SC (Garvey et al. 2005; Paz et al. 2006; Walker et al. 2007). We used a parent-reported PANS questionnaire, clinic visit data recorded in the EMR, and email and phone communications (also reported in the EMR and personal communication) to help inform the outcome variables. The research assistant (K.B.) who conducted the retrospective chart review was not blinded to treated versus untreated flares. In addition, there are unmeasured biases with regards to the clinicians and parents' choice to use corticosteroids. However, we did demonstrate that the group of patients who received at least one course of corticosteroids did, indeed, have worse impairment at time of entry to our clinic compared with the patients who never received corticosteroids (Table 1).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that oral corticosteroids may shorten PANS flare durations, and that early oral corticosteroid treatment may lead to a more robust response, which is consistent with the impact of corticosteroids in most inflammatory diseases (asthma, juvenile arthritis, etc.). We found that longer courses of corticosteroids resulted in more durable responses. This finding is similar to studies in SC, which indicated that higher doses of corticosteroids administered over a longer period yielded greater symptom reduction and shorter illness duration (Barash et al. 2005; Paz et al. 2006; Walker et al. 2007).

Clinical Significance

The results from this retrospective data evaluation warrant a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to definitively evaluate corticosteroid impact on PANS symptoms. The high rate of relapse after oral corticosteroid treatment calls for identification of other agents that may confer a sustained response. Adjunctive therapies to consider include daily low-dose corticosteroids (as with other inflammatory diseases such as lupus and asthma) and corticosteroid-sparing agents. This study does demonstrate that, for PANS and PANDAS relapses, corticosteroids are associated with improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms and shorter flare durations. In the absence of clinical trial data, coupled with the safety of short steroid courses, the authors recommend using steroids to treat PANS flares (Frankovich et al. 2017).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Susan Swedo, National Institute of Mental Health, the PANDAS Physician Network, Dr. Kiki Chang, Stanford School of Medicine, and all the faculty and staff at the Stanford Children's Health and the Stanford PANS clinic who make caring for children with PANS possible. This work was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health and the PANDAS Physician Network.

Disclosures

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Allen AJ, Leonard HL, Swedo SE: Case study: A new infection-triggered, autoimmune subtype of pediatric OCD and Tourette's syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:307–311, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armangue T, Petit-Pedrol M, Dalmau J: Autoimmune encephalitis in children. J Child Neurol 27:1460–1469, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asbahr FR, Negrao AB, Gentil V, Zanetta DM, da Paz JA, Marques-Dias MJ, Kiss MH: Obsessive-compulsive and related symptoms in children and adolescents with rheumatic fever with and without chorea: A prospective 6-month study. Am J Psychiatry 155:1122–1124, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asbahr FR, Ramos RT, Negrao AB, Gentil V: Case series: Increased vulnerability to obsessive-compulsive symptoms with repeated episodes of Sydenham chorea. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:1522–1525, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale JF, Jr.: Virus and immune-mediated encephalitides: Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Pediatr Neurol 53:3–12, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barash J, Margalith D, Matitiau A: Corticosteroid treatment in patients with Sydenham's chorea. Pediatr Neurol 32:205–207, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimberg L, Benhar I, Mascaro-Blanco A, Alvarez K, Lotan D, Winter C, Klein J, Moses AE, Somnier FE, Leckman JF, Swedo SE, Cunningham MW, Joel D: Behavioral, pharmacological, and immunological abnormalities after streptococcal exposure: A novel rat model of Sydenham chorea and related neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 37:2076–2087, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carapetis JR, Beaton A, Cunningham MW, Guilherme L, Karthikeyan G, Mayosi BM, Sable C, Steer A, Wilson N, Wyber R, Zuhlke L: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2:15084, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K, Frankovich J, Cooperstock M, Cunningham MW, Latimer ME, Murphy TK, Pasternack M, Thienemann M, Williams K, Walter J, Swedo SE: Clinical evaluation of youth with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS): Recommendations from the 2013 PANS Consensus Conference. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25:3–13, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperstock M, Swedo S, Pasternack M, Murphy T: Clinical management of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS): Part III—Treatment and prevention of infections. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol, 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1089/cap.2016.0151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CJ, Sharma M, Leckman JF, Zuccolo J, Zuccolo A, Kovoor A, Swedo SE, Cunningham MW: Brain human monoclonal autoantibody from sydenham chorea targets dopaminergic neurons in transgenic mice and signals dopamine D2 receptor: Implications in human disease. J Immunol 191:5524–5541, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutforth T, DeMille MM, Agalliu I, Agalliu D: CNS autoimmune disease after infections: Animal models, cellular mechanisms and genetic factors. Future Neurol 11:63–76, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dileepan T, Smith ED, Knowland D, Hsu M, Platt M, Bittner-Eddy P, Cohen B, Southern P, Latimer E, Harley E, Agalliu D, Cleary PP: Group A Streptococcus intranasal infection promotes CNS infiltration by streptococcal-specific Th17 cells. J Clin Invest 126:303–317, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duzova A, Bakkaloglu A: Central nervous system involvement in pediatric rheumatic diseases: Current concepts in treatment. Curr Pharm Des 14:1295–1301, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster C, Burek M, Romero IA, Weksler B, Couraud PO, Drenckhahn D: Differential effects of hydrocortisone and TNFalpha on tight junction proteins in an in vitro model of the human blood-brain barrier. J Physiol 586:1937–1949, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankovich J, Swedo S, Murphy T, Dale RC, Agalliu D, Williams K, Daines M, Hornig M, Chugani H, Sanger T, Muscal E, Pasternack M, Cooperstock M, Gans H, Zhang Y, Cunningham M, Bernstein G, Bromberg R, Willet T, Brown K, Farhadian B, Chang K, Geller D, Hernandez J, Sherr J, Shaw R, Latimer E, Leckman J, Thienemann M: Clinical management of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS): Part II—Use of immunomodulatory therapies. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol, 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1089/cap.2016.0148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankovich J, Thienemann M, Pearlstein J, Crable A, Brown K, Chang K: Multidisciplinary clinic dedicated to treating youth with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome: Presenting characteristics of the first 47 consecutive patients. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25:38–47, 2015a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankovich J, Thienemann M, Rana S, Chang K: Five youth with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome of differing etiologies. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25:31–37, 2015b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey MA, Snider LA, Leitman SF, Werden R, Swedo SE: Treatment of Sydenham's chorea with intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, or prednisone. J Child Neurol 20:424–429, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkerohe D, Smikalla D, Schoebel A, Haghikia A, Zoidl G, Haase CG, Schlegel U, Faustmann PM: Dexamethasone prevents LPS-induced microglial activation and astroglial impairment in an experimental bacterial meningitis co-culture model. Brain Res 1329:45–54, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KL, Hornig M, Yaddanapudi K, Jabado O, Lipkin WI: A murine model for neuropsychiatric disorders associated with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection. J Neurosci 24:1780–1791, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Williams MT, Chugani HT: Evaluation of basal ganglia and thalamic inflammation in children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection and Tourette syndrome: A positron emission tomographic (PET) study using 11C-[R]-PK11195. J Child Neurol 30:749–756, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotan D, Benhar I, Alvarez K, Mascaro-Blanco A, Brimberg L, Frenkel D, Cunningham MW, Joel D: Behavioral and neural effects of intra-striatal infusion of anti-streptococcal antibodies in rats. Brain Behav Immun 38:249–262, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macri S, Ceci C, Onori MP, Invernizzi RW, Bartolini E, Altabella L, Canese R, Imperi M, Orefici G, Creti R, Margarit I, Magliozzi R, Laviola G: Mice repeatedly exposed to Group-A beta-Haemolytic Streptococcus show perseverative behaviors, impaired sensorimotor gating, and immune activation in rostral diencephalon. Sci Rep 5:13257, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro-Checa C, Zirkzee EJ, Huizinga TW, Steup-Beekman GM: Management of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: Current approaches and future perspectives. Drugs 76:459–483, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia DP, Teixeira AL, Jr., Quintao Cunningham MC, Cardoso F: Obsessive compulsive behavior, hyperactivity, and attention deficit disorder in Sydenham chorea. Neurology 64:1799–1801, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muls N, Jnaoui K, Dang HA, Wauters A, Van Snick J, Sindic CJ, van Pesch V: Upregulation of IL-17, but not of IL-9, in circulating cells of CIS and relapsing MS patients. Impact of corticosteroid therapy on the cytokine network. J Neuroimmunol 243:73–80, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TK, Patel PD, McGuire JF, Kennel A, Mutch PJ, Parker-Athill EC, Hanks CE, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Toufexis MD, Dadlani GH, Rodriguez CA: Characterization of the pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome phenotype. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25:14–25, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO: Mplus User's Guide (7th ed). Los Angeles, CA, Muthén & Muthén, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Nosadini M, Mohammad SS, Ramanathan S, Brilot F, Dale RC: Immune therapy in autoimmune encephalitis: A systematic review. Expert Rev Neurother 15:1391–1419, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak M, Guest C: Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist 29:798–803, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orefici G, Cardona F, Cox CJ, Cunningham MW: Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). In: Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations. Edited by Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA. Oklahoma City (OK), University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (c) The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 2016, pp. 1–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz JA, Silva CA, Marques-Dias MJ: Randomized double-blind study with prednisone in Sydenham's chorea. Pediatr Neurol 34:264–269, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Rudmik L, Soler ZM: Medical therapies for adult chronic sinusitis: A systematic review. JAMA 314:926–939, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvergleid AJ, Ballow M: Overview of intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) therapy. In: UpToDate. Edited by Post TW, Schrier SL, Stiehm ER, Tirnauer JS, and Feldweg AM. Waltham, MA, UpToDate, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Swedo SE: Sydenham's chorea. A model for childhood autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders. JAMA 272:1788–1791, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedo SE, Leckman JF, Rose NR: Modifying the PANDAS criteria to describe PANS (pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome). Pediatr Ther 2:1–8, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, Mittleman B, Allen AJ, Perlmutter S, Lougee L, Dow S, Zamkoff J, Dubbert BK: Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: Clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am J Psychiatry 155:264–271, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Schapiro MB, Casey BJ, Mannheim GB, Lenane MC, Rettew DC: Sydenham's chorea: Physical and psychological symptoms of St Vitus dance. Pediatrics 91:706–713, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedo SE, Rapoport JL, Cheslow DL, Leonard HL, Ayoub EM, Hosier DM, Wald ER: High prevalence of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with Sydenham's chorea. Am J Psychiatry 146:246–249, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AR, Tani LY, Thompson JA, Firth SD, Veasy LG, Bale JF, Jr: Rheumatic chorea: Relationship to systemic manifestations and response to corticosteroids. J Pediatr 151:679–683, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker KG, Lawrenson J, Wilmshurst JM: Neuropsychiatric movement disorders following streptococcal infection. Dev Med Child Neurol 47:771–775, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KA, Swedo SE: Post-infectious autoimmune disorders: Sydenham's chorea, PANDAS and beyond. Brain Res 1617:144–154, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaddanapudi K, Hornig M, Serge R, De Miranda J, Baghban A, Villar G, Lipkin WI: Passive transfer of streptococcus-induced antibodies reproduces behavioral disturbances in a mouse model of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection. Mol Psychiatry 15:712–726, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]