Abstract

Understanding how often patients seek care from multiple hospitals is important for care of individuals and populations, but it is not routinely measured because of lack of data. This study used data from a health information exchange (HIE) to measure the frequency with which patients seek care from multiple hospitals. This was a retrospective cohort study (2010–2011) of all patients who sought emergency department (ED) or inpatient care at 6 participating hospitals in Manhattan. The study found that all 6 hospitals shared patients with each of the other hospitals and that 10.0% of all ED visits and 9.1% of all admissions were for patients who had been seen in a different hospital in the past 12 months. Patients are frequently seen by multiple hospitals, which poses a challenge for clinical care and population management. By capturing which patients are seen where and when, HIEs are well suited for facilitating population management.

Introduction

In the United States, patients routinely seek care from multiple providers in multiple practices and health systems.1 Although patients may assume that communication across providers is routine, providers do not always share clinical information with each other in a timely manner. This can result in relevant clinical data being missing at the point of care.2,3 When relevant data are missing, providers still make decisions regarding diagnosis and treatment, but harm can occur. For example, patients may endure unnecessary repeat testing and/or receive prescriptions for new medications that interact with the patients' existing regimen. Lack of communication across providers can ultimately result in unnecessary hospital admissions.4

One potential solution to this problem is an electronic health information exchange (HIE). An HIE allows providers to access clinical information on their patients, regardless of the ordering provider; send information directly to another provider for a common patient; and receive alerts when their patients have other health care encounters.5,6 Although HIEs have been shown to be effective in reducing repeat testing and reducing hospitalizations,7–11 they have not yet been adopted widely.

Several barriers to the adoption of HIEs are known, including cost, technical challenges, privacy concerns, and competition.12 Another less-discussed barrier to the adoption of an HIE is the potential perception by any given health care provider or hospital that patient movement across multiple providers or health systems is not a significant issue for their population. If a hospital does not believe that the problem occurs frequently enough, it could easily conclude that understanding or addressing the problem is not worth the cost.

The frequency with which patients seek care from multiple health systems has not been commonly measured. This is likely because data have not been routinely available for capturing such a measure. No single provider or hospital can easily determine how often their patients seek care elsewhere, and any given payer only captures its own patients, which usually comprises only a fraction of the provider's overall population of patients. Some previous studies have used HIEs to measure the frequency with which patients seek care from multiple health systems; however, several of these have only considered patients with a specific disease or category of disease.13–16 Such disease-specific studies may underestimate the overall frequency of patient sharing across hospitals.

Thus, this study used data from an HIE to determine the frequency with which patients seek care from multiple health systems in a major US city, regardless of disease.

Methods

Study design

The research team conducted a longitudinal cohort study of patients who sought care between 2010 and 2011 from at least 1 of 6 major hospitals in Manhattan (Beth Israel Medical Center, Mount Sinai Medical Center, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, New York University Medical Center, Roosevelt Hospital, and St. Luke's Hospital). The Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medical College determined that the study protocol was exempt from review because the data set used was de-identified.

Data source

The research team used data from an HIE called Healthix (Healthix, Inc., New York, NY).17 More specifically, data were used from the portion of the Healthix organization that had been called the New York Clinical Information Exchange (NYCLIX) before a merger with another organization. The NYCLIX data set included all emergency department (ED) and inpatient visits for patients who sought care at the 6 participating hospitals during the calendar years 2010 and 2011. At the time of the study, NYCLIX was being used operationally by only a small group of pilot users at several sites; thus, the data reflect patients' patterns of health care utilization but do not imply patterns influenced by usage of HIE for clinical purposes. NYCLIX was one of several regional HIEs funded, in part, by the New York Department of Health through a program called Healthcare Efficiency and Affordability Law for New Yorkers Capital Grant Program (HEAL NY).18

Data analysis

Patients who were seen in the ED or had an inpatient admission at least once at a participating hospital during the study period were included. These patients also may have received additional hospital-based ambulatory services, such as outpatient department visits, laboratory tests, and radiology tests, although these were not captured.

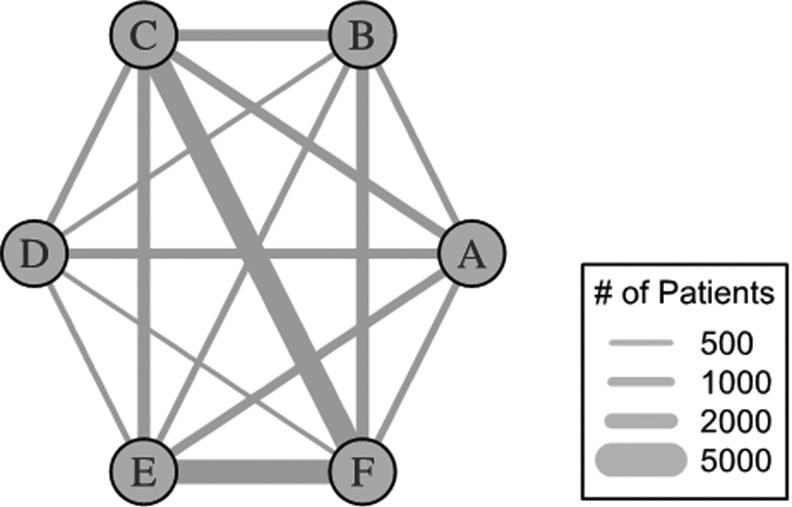

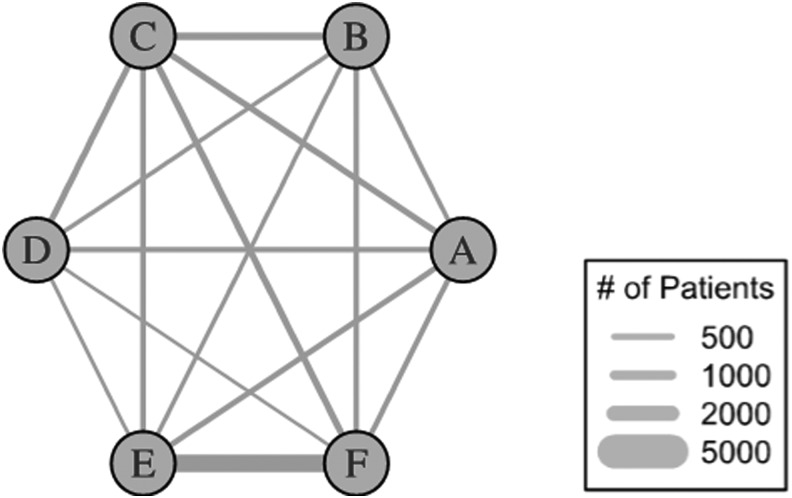

The research team conducted 2 main analyses. The first analysis considered only patient encounters in 2011. The team calculated the total number of patients who sought ED or inpatient care from at least 1 of the participating hospitals and then calculated the number of patients who sought ED or inpatient care at multiple hospitals that year. R statistical software was used to generate graphical displays to determine which hospitals' patients went to other hospitals in the same year.19 In these figures, the hospitals are depicted as circles, and patients who visit multiple hospitals are depicted as lines connecting the hospitals they visited. The thickness of the lines is proportional to the number of patients “shared” by a given pair of hospitals, with thicker lines illustrating greater numbers of shared patients.

The second analysis considered encounters from both 2010 and 2011. For each ED or inpatient encounter in 2011, the research team looked back over the previous 12 months to determine if that patient had been seen in a different hospital for ED or inpatient care. This analysis allowed the specific 12-month window to vary, fixing each encounter's “time zero” as the date of that encounter in 2011. The team calculated the number and proportion of encounters in 2011 for which patients had also visited another hospital in the previous 12 months.

Results

The research team identified 566,907 unique patients who were seen in the ED or inpatient settings in the 6 participating hospitals in 2011. Of those, 443,430 (78%) unique patients were seen in the ED, for a total of 739,888 ED visits (an average of 1.7 ED visits for each patient with at least 1 ED visit). Of the total number of unique patients, 243,122 (43%) were admitted to the hospital at least once, for a total of 350,681 admissions (an average of 1.4 admissions for each patient with at least 1 admission).

The first analysis found that each of the 6 hospitals shared patients with every other hospital. In 2011, given any pair of hospitals, between 321 and 3535 patients (average 1289) were seen in both EDs that year (Fig. 1). Similarly, in 2011, given any pair of hospitals, between 109 and 2417 patients (average 556) were seen in both inpatient settings that year (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Frequency of patients receiving care from multiple emergency departments in a single city in 2011. The average number of patients shared by any pair of emergency departments was 1289 (range between 321 and 3535).

FIG. 2.

Frequency of patients receiving care from multiple inpatient settings in a single city in 2011. The average number of patients shared by any pair of inpatient settings was 556 (range between 109 and 2417).

In the second analysis, looking over time for the entire group of patients, there were 74,196 ED visits (10.0% of all ED visits) for which the patient had been seen elsewhere in the previous 12 months. Similarly, there were 31,967 inpatient admissions (9.1% of all inpatient admissions) for which the patient had been seen elsewhere in the previous 12 months.

The probability of patients being seen by multiple health systems varied slightly by hospital, but all hospitals were affected. Depending on the institution, between 6.8% and 16.9% of ED visits and between 6.6% and 26.5% of inpatient admissions were for patients who had been seen elsewhere in the previous 12 months.

Discussion

This study of 6 hospitals in a major city found that 10% of ED visits and 9% of admissions were for patients who had been seen in a different hospital in the previous 12 months. It also was found that each hospital shared patients with every other hospital in a single year; that is, all 15 possible pairs of hospitals shared patients.

This study is consistent with and builds on the work of previous studies. For example, investigators in Massachusetts found that 31% of patients visited 2 or more hospitals out of 77 hospitals in that state over a 5-year study period.20 Investigators in Indiana found that 40% of ED visits were for patients having data at multiple institutions, across more than 80 EDs in that state over a 3-year study period.21 The present study considers a city rather than a state, 6 hospitals rather than tens of hospitals, and 2 years of data rather than 3–5 years of data. That substantial rates of use of multiple hospitals still were found is striking and underscores the fact that this issue is pervasive and not found only in very large-scale studies. This study also illustrates the high rate of patient “crossover” among academic health centers, whereas previous studies included mostly community hospitals.

There are several implications of this finding. First, no hospital in the present study was “spared” from the problem of patients seeking care elsewhere, and every hospital shared patients with every other. The “completeness” of this picture is important, as it suggests a universality to this problem, potentially regardless of hospital quality and regardless of patients' insurance types. That patients seek care from multiple providers is a dominant feature of American health care; however, this feature will take on increasing importance as physician reimbursement shifts from fee for service to “value-based payments” and other alternative models of payment.22 Value-based payments, such as those associated with accountable care organizations, require providers to take clinical and financial responsibility for a specific population of patients.23 Providers are thus newly responsible for the cost and consequences when patients seek care elsewhere. Knowing how often and when patients seek care elsewhere is critical.

Another important aspect of this study is that it was able to characterize patterns of care using data from an electronic HIE. At the time of the study, the HIE was not being used widely for clinical decision making, but its existence enabled a rare, comprehensive look at the health care delivery in a city. Thus, although the finding of how frequently patients seek care elsewhere may be important to providers and health systems, the ability to calculate it depends on the availability of data. The success of population management may very well require greater access to comprehensive data such as those from HIEs, as no single payer or provider can generate comparable data. It should be noted that not all HIEs have the technical architecture to support population management, but the concept that some HIEs can support these activities is worthy of greater attention.24 HIEs also, of course, offer clinical data that can inform medical decision making, bridging information gaps across providers in different health systems caring for common patients.25

This study has several limitations. Although it includes 6 major hospitals in Manhattan, 6 other hospitals in Manhattan were not included because they were not participating in the HIE at the time of the study. In addition, this study does not capture ambulatory care. Both of these limitations would cause the present study to underestimate the extent of health care fragmentation; true rates are even higher than those found. Another limitation is that the research team cannot determine if these patterns are related to patient preferences, ambulance algorithms for the nearest hospital, or physician referral patterns; future studies could attempt to separate these. The team also did not have access to detailed patient characteristic data; additional studies could examine this more fully and determine which patients are most at risk for seeking care from multiple hospitals. Finally, the team did not have access to characteristics of the participating hospitals because of being blinded to their identities; therefore, the team cannot determine any hospital-based factors in the variability in rates of crossover observed.

In conclusion, this study found that 10% of ED visits and 9% of admissions were for patients who had been seen in a different hospital in the previous 12 months. All 6 hospitals in the study were affected by this phenomenon and all hospitals shared patients with every other hospital. As provider reimbursement changes to emphasize population management, hospitals will need to grapple more directly with this patient movement than they have in the past. Data sources that can track patient movement will be increasingly important, and HIEs are uniquely suited to offer that type of information.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Healthix for providing access to the data.

Author Disclosure Statement

Drs. Kern, Grinspan, Shapiro, and Kaushal declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Greater New York Hospital Foundation.

Prior Presentation

An earlier version of this work was presented at the national meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in San Diego, California, in April 2014.

References

- 1.Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1130–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. . Missing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA 2005;293:565–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiell A, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, van Walraven C. Prevalence of information gaps in the emergency department and the effect on patient outcomes. CMAJ 2003;169:1023–1028 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witherington EM, Pirzada OM, Avery AJ. Communication gaps and readmissions to hospital for patients aged 75 years and older: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore T, Shapiro JS, Doles L, et al. . Event detection: a clinical notification service on a health information exchange platform. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2012;2012:635–642 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutteridge DL, Genes N, Hwang U, Kaplan B, The GEDI WISE Investigators, Shapiro JS. Enhancing a geriatric emergency department care coordination intervention using automated health information exchange-based clinical event notification. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2014;2:1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisse ME, Johnson KB, Nian H, et al. . The financial impact of health information exchange on emergency department care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:328–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overhage JM, Dexter PR, Perkins SM, et al. . A randomized, controlled trial of clinical information shared from another institution. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:14–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vest JR, Kaushal R, Silver M, Hentel K, Kern LM. Health information exchange and the frequency of repeat medical imaging. Am J Manag Care 2014;11 Spec No. 17:eSP16–eSP24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vest JR, Kern LM, Campion TR, Jr, Silver MD, Kaushal R. Association between use of a health information exchange system and hospital admissions. Appl Clin Inform 2014;5:219–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vest JR, Kern LM, Silver M, Kaushal R. The potential for community-based health information exchange systems to reduce hospital readmissions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vest JR, Gamm LD. Health information exchange: persistent challenges and new strategies. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;17:288–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grinspan ZM, Abramson EL, Banerjee S, Kern LM, Kaushal R, Shapiro JS. Potential value of health information exchange for people with epilepsy: crossover patterns and missing clinical data. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2013;2013:527–536 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grinspan ZM, Abramson EL, Banerjee S, Kern LM, Kaushal R, Shapiro JS. People with epilepsy who use multiple hospitals; prevalence and associated factors assessed via a health information exchange. Epilepsia 2014;55:734–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grinspan ZM, Shapiro JS, Abramson EL, Jung HY, Kaushal R, Kern LM. Hospital crossover increases utilization for people with epilepsy: a retrospective cohort study. Epilepsia 2015;56:147–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laborde DV, Griffin JA, Smalley HK, Keskinocak P, Mathew G. A framework for assessing patient crossover and health information exchange value. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:698–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healthix. Home page. http://healthix.org/ Accessed March11, 2016

- 18.Kern LM, Barron Y, Abramson EL, Patel V, Kaushal R. HEAL NY: promoting interoperable health information technology in New York State. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:493–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The R Project. The R project for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/ Accessed March11, 2016

- 20.Bourgeois FC, Olson KL, Mandl KD. Patients treated at multiple acute health care facilities: quantifying information fragmentation. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1989–1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finnell JT, Overhage JM, Grannis S. All health care is not local: an evaluation of the distribution of emergency department care delivered in Indiana. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011;2011:409–416 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder SA, Frist W. Phasing out fee-for-service payment. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2029–2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berwick DM. Launching accountable care organizations—the proposed rule for the Medicare Shared Savings Program. N Engl J Med 2011;364:e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro JS, Johnson SA, Angiollilo J, Fleischman W, Onyile A, Kuperman G. Health information exchange improves identification of frequent emergency department users. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:2193–2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kern LM, Dhopeshwarkar R, Barron Y, Wilcox A, Pincus H, Kaushal R. Measuring the effects of health information technology on quality of care: a novel set of proposed metrics for electronic quality reporting. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2009;35:359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]