Abstract

Background

Heart failure is an inflammatory disease. Patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) exhibit significant inflammatory activity upon admission. We hypothesized that Interleukin-1 (IL-1) blockade, with anakinra (Kineret™, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum), would quench the acute inflammatory response in patients with ADHF.

Methods

We randomized 30 patients with ADHF, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF<40%), and elevated C reactive protein (CRP) levels (≥5 mg/L) to either anakinra 100 mg twice daily for 3 days followed by once daily for 11 days or matching placebo, in a 1:1 double blinded fashion. We measured daily CRP plasma levels using a high-sensitivity assay during hospitalization and then again at 14 days and evaluated the area-under-the-curve (AUC) and interval changes (delta).

Results

Treatment with anakinra was well tolerated. At 72 hours, anakinra reduced CRP by 61% versus baseline, compared to a 6% reduction among patients receiving placebo (P=0.004 anakinra versus placebo).

Conclusions

IL-1 blockade with anakinra reduces the systemic inflammatory response in patients with ADHF. Further studies are warranted to determine whether this anti-inflammatory effect translates into improved clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Interleukin-1, Inflammation, Acute Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome characterized by dyspnea (shortness of breath) and fatigue. Patients typically experience a gradual decline in cardiac function over time, punctuated by periodic exacerbations that result in hospitalization for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).1 Despite the demonstrated benefits of contemporary strategies during chronic treatment, the pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for acute decompensations of HF remain largely unexplained. Consequently, hospitalization rates for ADHF have tripled over the last 25 years and ADHF has now become the leading cause for hospitalization among US patients >65 years old.2–4 Mortality during ADHF admission is estimated at 3-4% and nearly 50% of discharged patients will be re-hospitalized within 90 days. Numerous clinical trials exploring the management of ADHF have consistently failed to reduce HF morbidity and mortality after discharge.5–13 Taken together, these findings demonstrate the urgent unmet need to develop novel treatment strategies for ADHF and suggest that the current treatment paradigm fails to interrupt one or more key pathophysiologic mechanisms.

The evidence for the presence of inflammation in ADHF is overwhelming.14–18 Many unanswered questions remain, however, regarding what drives the systemic inflammatory response and whether inflammation plays a key role in decompensation or is merely a marker of disease. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) is an apical inflammatory cytokine that is moderately elevated in most forms of HF, but becomes markedly elevated during ADHF admission as measured by C-reactive protein and IL-6, surrogate biomarkers of IL-1 activity.14,19–22 Given that IL-1 is sufficient to induce cardiac dysfunction in cellular and animal models of HF,21,22 we proposed to investigate whether IL-1 activity is a modifiable factor in the systemic inflammatory response during ADHF.

Methods

We designed a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled pilot study. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01936844) and operated under an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) held by the authors (IND 118,957). The study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board and all patients provided written informed consent.

To be eligible for enrollment, patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) Primary diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure within the last 24 hours as evidenced by dyspnea at rest and evidence of elevated cardiac filling pressure (or pulmonary congestion) as evidenced by pulmonary congestion/edema at physical exam (or chest radiography), plasma B-type natriuretic peptide ≥200 pg/mL, or invasive measure of LV end-diastolic pressure >18 mmHg or pulmonary artery occluding pressure (wedge) >16 mmHg; (2) LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF <40%) during the index hospitalization or prior 12 months; (3) Age ≥18 years old; (4) Willing and able to provide written informed consent; (5) Screening plasma C-reactive protein ≥5 mg/L. Patients were excluded for any of the following exclusion criteria: (1) Primary diagnosis for admission for something other than decompensated heart failure, including diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes, hypertensive urgency/emergency, tachy- or brady-arrhythmias; (2) Concomitant clinically significant comorbidities that would interfere with the execution or interpretation of the study including but not limited to acute coronary syndromes, uncontrolled hypertension or orthostatic hypotension, tachy- or brady-arrhythmias, acute or chronic pulmonary disease or neuromuscular disorders affecting respiration; (3) Recent (previous 3 months) or planned cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), coronary artery revascularization procedures, or heart valve surgeries; (4) Previous or planned implantation of left ventricular assist devices or heart-transplant; (5) Chronic use of intravenous inotropes; (6) Recent (<14 days) use of immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory drugs (not including NSAIDs); (7) Chronic inflammatory disorder (including but not limited to rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus); (8) Active infection (of any type); (9) Chronic/recurrent infectious disease (including HBV, HCV, and HIV/AIDS); (10) Prior (within the past 10 years) or current malignancy; (11) Any comorbidity limiting survival or ability to complete the study; (12) End stage kidney disease requiring renal replacement therapy; (13) Neutropenia (<2,000/mm3) or Thrombocytopenia (<50,000/mm3); (14) Pregnancy.

Data Analysis

The primary analysis compared the area-under-the-curve (AUC) at 72 hours for C-reactive protein as measured by high sensitivity assay (hsCRP) between allocation groups. For patients who were discharged prior to 72 hours, but completed at least 48 hours of treatment during their hospitalization, the last remaining blood draw prior to discharge was carried forward to be included in the 72 hours analysis. A limited transthoracic echocardiogram was performed at baseline and 14-day follow-up according to American Society of Echocardiography Recommendations to measure LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes in the apical 4- and 2-chamber views; the transmitral flow and mitral annulus tissue Doppler spectra were acquired from the apical 4-chamber view.23 Additional exploratory analyses included CRP at 14 days, other inflammatory biomarkers, changes in echocardiographic measures of cardiac function (measured at baseline and 14-day follow-up), and assessment of clinical outcomes throughout the 14-day follow-up such as adverse events, length of stay, hospital readmission, and time-to-events. All assessments were performed by investigators blinded to treatment allocation. To account for variation in baseline CRP, an additional AUC calculation was performed using CRP values normalized for baseline values (i.e. expressed as a fraction of baseline CRP). Using this approach, the baseline CRP is expressed as 1.0 and a CRP that remained unchanged throughout the study would result in an AUC of 3.0 units after 72 hours and 14.0 units after 14 days.

Descriptive summaries of continuous measurements are reported as median and interquartile range to account for potential deviation from Guassian distribution. Descriptive summaries of categorical measurements are reported as frequency, proportion, and 95% confidence intervals. Differences between treatment groups were computed using the Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples or Fisher’s exact test for discrete variables. Paired analyses of effects versus baseline were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables.

The sample size for the pilot study is based upon the expected CRP AUC responses at 72 hours and 14 days for patients treated with anakinra versus placebo. In a study of nesiritide versus nitroglycerin in a similar population with ADHF, Chow et al reported a baseline CRP of 25 ± 6 mg/L that remained unchanged after 48 hours continuous treatment.19 We therefore anticipated minimal changes in CRP prior to 48 hours, moderate reductions in CRP between 48 hours and discharge, followed by reductions to a mean value of 5 mg/L at the 14 days follow-up. Based on our proof-of-concept study in patients with stable systolic HF in which anakinra produced a 90% reduction in CRP at 14 days,21 we anticipated a 50% reduction of CRP within 72 hours of anakinra treatment, followed by a reduction to less than 2 mg/L at the 14 days follow-up, resulting in a 50% relative AUC reduction versus placebo at 14 days. These assumptions provided 87% power to detect a significant difference in CRP AUC with a sample size of 30 patients.

Results

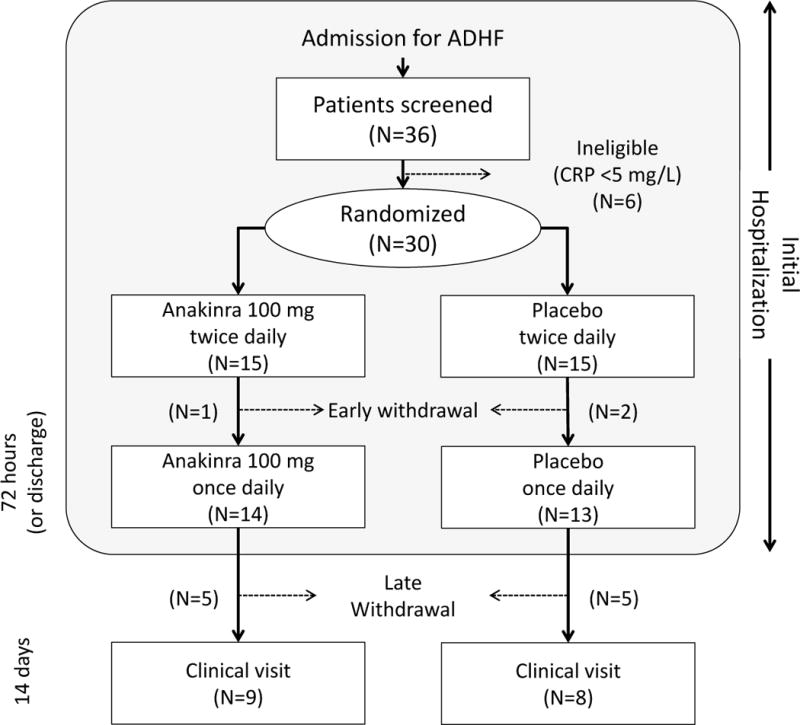

Beginning on January 30, 2014, consecutive patients presenting to our institution with suspected heart failure were reviewed for eligibility. Patients that met the eligibility criteria upon preliminary review were approached for potential enrollment (Figure 1). A total of 36 patients provided informed consent and underwent CRP screening, resulting in 30 patients who met entry criteria and underwent randomization. Patient demographical data and clinical characteristics are displayed in Table 1. In general, the study population consisted of middle-aged, African American men with moderate-to-severe systolic dysfunction and high prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. There were no significant differences between allocation groups in patient demographics or clinical characteristics.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for patient enrollment in study

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and characteristics

| Anakinra (N=15) | Placebo (N=15) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60 [49, 64] |

54 [49, 66] |

0.71 |

| Gender (male) | 67% | 80% | 0.69 |

| Race (AA) | 87% | 73% | 0.62 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.9 [27.4, 39.4] |

40.8 [33.4, 46.9] |

0.20 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 47% | 20% | 0.24 |

| Prior CABG | 20% | 7% | 0.61 |

| Baseline LVEF | 24.6 [20.2, 33.8] |

32.5 [21.8, 39.0] |

0.19 |

| Diabetes | 67% | 67% | 0.70 |

| Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter | 27% | 47% | 0.45 |

| Hypertension | 93% | 100% | 0.96 |

| Tobacco use | 27% | 13% | 0.62 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 67% | 67% | 0.70 |

| Prior Stroke | 13% | 0% | 0.48 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7% | 0% | 0.96 |

| CKD | 60% | 40% | 0.47 |

| COPD | 13% | 20% | 0.98 |

| Medications prior to admission | |||

| Loop diuretics | 73% | 80% | 0.98 |

| Loop diuretic dose (mg) | 80 [15, 160] |

80 [60, 160] |

0.73 |

| β-blocker | 79% | 80% | 0.69 |

| ACEI/ARB | 64% | 53% | 0.82 |

| Statin | 71% | 67% | 0.87 |

| Aldosterone inhibitor | 29% | 40% | 0.82 |

| Hydralazine | 36% | 40% | 0.87 |

| Nitrates | 31% | 21% | 0.85 |

| Aspirin | 64% | 47% | 0.58 |

| P2Y12 antagonist | 7% | 0% | 0.97 |

| Metformin | 0% | 20% | 0.96 |

| Insulin | 36% | 20% | 0.58 |

Abbreviations: AA=African America; ACEI=Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor; ARB=Angiotensin Receptor Blocker; BMI=Body Mass Index; CABG=Coronary Artery Bypass Graft; CKD=Chronic Kidney Disease; COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; LVEF=Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction;

Fourteen patients in the anakinra group (93%) and 13 patients in the placebo group (87%) completed the study protocol through the first 72 hours (or discharge) and were converted to once-daily dosing. One patient in each group had treatment suspended upon discovery of an infection (Clostridium difficile colitis, peritonitis) that was subsequently considered to have been present prior to enrollment. These 2 patients were therefore excluded from all analyses. One additional patient in the placebo group was transferred to another hospital on Day 2 of treatment and was withdrawn from the study. Two additional patients in the anakinra group and 1 additional patient in the placebo group were discharged before 48 hours and were not included in the 72 hours analyses. A total of 9 patients in the anakinra group (60%) and 8 patients in the placebo group (53%) returned to clinic for the 14-day clinical follow-up.

Plasma biomarkers levels are presented in Table 2. Patients exhibited pronounced inflammatory activity at baseline, as evidenced by the median baseline CRP of 23.8 [10.9 – 46.9 mg/L] among all patients enrolled. During the first 72 hours of treatment, CRP remained largely unchanged among patients randomized to placebo (−6.0% [−32.6%, 54.5%], P=0.88 versus baseline), but was significantly reduced among patients treated with anakinra (−61.0% [−71.2%, −51.5%], P=0.002 versus baseline, P=0.004 versus placebo, Figure 2). Patients receiving anakinra were also more likely to experience a 50% reduction in CRP at 72 hours (75% versus 17%, P=0.008).

Table 2.

Biomarkers during treatment (14 days)

| Anakinra | Placebo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Biomarker | Baseline | 72 hours | 14 days | Baseline | 72 hours | 14 days |

| CRP (mg/L) | 22.3 [10.8, 95.9] | 13.8 [4.6, 22.4] | 1.3 [0.8, 1.85]* | 27.4 [12.0, 47.2] | 24.2 [7, 40.8] | 4.4 [1.8, 20.8]* |

| −61% [−71, −52]** | −98% [−99, −90]** | −6% [−32, +54]** | −85% [−92, −56]** | |||

|

| ||||||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 2.72 [1.54, 3.97] | 0.79 [0.59, 2.20]* | 0.44 [0.30, 0.90]* | 3.75 [2.18, 5.27] | 2.20 [1.81, 3.60]* | 0.72 [0.59, 1.74]* |

| −53% [−81, −36] | −89% [−92, −34] | −19% [−63, +5] | −65% [−90, −20] | |||

|

| ||||||

| NTproBNP (pg/mL) | 2921 [1825, 5056] | 1467 [950, 2939] | 1391 [928, 2086] | 3371 [955, 5268] | 1133 [730, 1912] | 1288 [618, 1562] |

| −42% [−55, −21] | −62% [−69, 0] | −42% [−71, −6] | −39% [−73, +97] | |||

|

| ||||||

| hsTnI (ng/L) | 50.8 [18.6, 320.9] | 66.8 [18.3, 139.3] | 31.5 [18.2, 138.2]* | 33.5 [23.2, 113.6] | 28.3 [15.8, 133.5] | 18.0 [8.9, 27.5]* |

| −42% [−60, −12] | −19% [−43, +4] | −19% [−38, +7] | −22% [−50, −13] | |||

|

| ||||||

| TNFα (pg/mL) | 1.50 [1.18, 1.92] | 1.70 [1.60, 2.10] | 1.40 [1.15, 2.30] | 1.70 [1.30, 2.35] | 1.25 [0.98, 1.92] | 1.45 [1.12, 2.02] |

| +14% [+5, +30] | +11% [0, 30] | −17% [−25, +22] | +6% [−36, 30] | |||

|

| ||||||

| IL-17A (pg/mL) | 0.45 [0.20, 0.72] | 0.30 [0.10, 0.80] | 0.45 [0.22, 1.35] | 0.60 [0.20, 1.40] | 0.40 [0.22, 0.40] | 0.30 [0.05, 0.55] |

| 0% [−75, +60] | +12% [−48, +148] | +21% [−85, +100] | −73% [−100, +200] | |||

|

| ||||||

| MPO (pmol/L) | 395 [274, 647] | 342 [271, 452]* | 263 [226, 495] | 505 [314, 603] | 581 [448, 665]* | 402 [210, 520] |

| −16% [−34, +3]* | −25% [−40, −17] | +7% [−12, +52]* | −34% [−44, −13] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Lp-PLA2 (ng/mL) | 132 [124, 160] | 146 [106, 190] | 118 [92, 146] | 152 [90, 200] | 170 [128, 205] | 151 [93, 169] |

| −11% [−35, +41] | −12% [45, −5] | +27% [8, 48] | −13% [−22, +44] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Galectin-3 (ng/mL) | 21.7 [15.8, 37.1] | 33.4 [18.9, 38.0] | 24.6 [16.5, 30.6] | 22.5 [16.8, 33.0] | 20.2 [17.7, 27.6] | 21.0 [14.4, 30.9] |

| +2% [−25, +22] | −20% [−39, +10] | +23% [−21, +33] | +2% [−20, +53] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 38 [9, 68] | 49 [12, 79] | 79 [32, 192] | 28 [9, 54] | 35 [11, 72] | 36 [17, 100] |

| +12% [−26, +36] | 0% [−10, +119] | −2% [−19, +67] | +38% [−8, +122] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) | 12 [8, 22] | 11 [7, 21] | 10 [6, 18] | 17 [4, 38] | 12 [4, 35] | 12 [4, 30] |

| 0% [−11, +5] | 0% [−10, +12] | 0% [−6, +8] | −11% [−25, 0] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 124 [71, 212] | 116 [68,192] | 80 [54, 261] | 110 [60, 144] | 94 [67, 122] | 134 [76, 216] |

| −4% [−20, 6] | −32 [−45, −27] | +9% [−11, +22] | +21% [−31, +54] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.65 [1.28, 1.90] | 1.70 [1.40, 2.05] | 1.70 [1.20, 2.45] | 1.30 [1.15, 1.70] | 1.35 [1.20, 1.70] | 1.35 [1.08, 1.40] |

| −3% [−10, +18] | 0% [−8, +38] | +7% [0, +22] | +12% [0, +17] | |||

|

| ||||||

| WBC (cells/μL) | 6.4 [4.9, 9.5] | 5.6 [3.4, 6.1] | 5.9 [3.7, 6.6] | 6.3 [5.7, 8.2] | 6.3 [5.9, 6.3] | 5.7 [4.9, 6.9] |

| −22% [−33, −14]** | −24% [−31, −11] | −9% [−16, 0]** | −17% [−32, +8] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.9 [10.2, 13.9] | 11.8 [10.3, 13.6] | 12.1 [10.6, 14.8] | 13.4 [10.0, 14.6] | 12.3 [10.2, 14.4] | 13.9 [12.2, 16.0] |

| +1% [−5, +5] | +8% [+3, +13] | −3% [−7, +11] | +7% [−3, +19] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Platelets (count/μL) | 210 [176, 250] | 222 [184, 268] | 236 [194, 375] | 221 [160, 266] | 220 [146, 280] | 249 [218, 312] |

| +19% [−3, +20] | +20% [−1, +46] | +5% [−17, +12] | +32% [+9, +52] | |||

|

| ||||||

| ANC (cells/μL) | 4.2 [2.9, 6.8] | 2.9 [1.6, 3.8]* | 3.3 [2.1, 4.4] | 4.8 [4.0, 5.8] | 4.3 [3.35, 5.6]* | 3.7 [3.2, 4.6] |

| −42% [−50, −24]** | −35% [−50, −20] | −12% [−21, +2]** | −21% [−42, +12] | |||

Abbreviations: ANC=Absolute Neutrophil Count; CRP=C-Reactive Protein; hsTnI=high sensitivity Troponin I; IL-6=Interleukin-6; IL-17=Interleukin-17; Lp-PLA2=Lipoprotein-associated Phospholipase A2 ; MPO=Myeloperoxidase; NTproBNP=N-Terminal Brain Natriuretic Peptide; TNFα=Tumor Necrosis Factor α; WBC=White Blood Cell.

P<0.05 (anakinra versus placebo);

P<0.01 (anakinra versus placebo).

Figure 2.

C-reactive protein (CRP) values for patients randomized to anakinra (panel A) versus placebo (panel B) during the first 72 hours of hospitalization. Boxes indicate median and interquartile ranges. Panel C shows normalized CRP and median relative changes throughout 14 days of treatment. Error bars represent interquartile range. Shaded area represents AUC for normalized CRP values. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 for anakinra versus placebo for normalized CRP values. Panel D shows individual patient changes in CRP (%) from baseline to 72 hours.

Upon completion of 14 days treatment, CRP was significantly lower among patients randomized to anakinra (1.30 [0.80, 1.85] mg/L) compared to placebo (4.45 [1.80, 20.75] mg/L, P=0.034 versus anakinra), reflecting relative reductions of 97.5% (anakinra) and 85.0% (placebo, P=0.006 versus anakinra, Figure 3). Patients receiving anakinra were more likely to achieve a “normalized” CRP value (<2 mg/L) at 14 days (78% versus 25%, P=0.040).

Figure 3.

C-reactive protein values for patients randomized to anakinra versus placebo at 14-day follow-up visit. Dashed line represents upper limit of normal value for CRP (2 mg/L). **P<0.01 (anakinra versus placebo)

There were no statistical differences between the treatment groups in the absolute values of CRP AUC0-3 or CRP AUC0-14, whereas AUC calculations based upon normalized CRP values, to take into account differences in baseline values, were 29% lower at 3 days among patients treated with anakinra (2.09 [1.73, 2.61]) versus placebo (2.93 [2.36, 3.79], P=0.023) and 52% lower at 14 days (anakinra 4.84 [3.50, 5.67] versus placebo 10.10 [7.71, 17.99], P=0.013).

Treatment with anakinra also produced significant reductions in IL-6 AUC0-3 and IL-6 AUC0-14 (Table 2)

Anakinra did not have any consistent effect on other biomarkers such as TNFα, IL-17, LpPLA2, leptin, adiponectin, NTproBNP, and galectin-3 (Table 2). There was an early reduction among patients receiving anakinra in myeloperoxidase activity at 72 hours, but this effect disappeared at the 14 days evaluation. Patients receiving anakinra exhibited higher concentrations of high sensitivity cardiac troponin I at the 14 days follow-up, although the relative reductions from baseline were comparable between allocation groups (−19% [anakinra] versus -22% [placebo], P=0.68, Table 2).

Treatment with anakinra was well tolerated. There were 6 adverse events (in 5 patients) treated with anakinra and 12 adverse events (in 10 patients) treated with placebo (OR 0.22 [0.04-1.09, P=0.064). Patient receiving anakinra exhibited significant reductions versus placebo in white blood cells and neutrophils after 72 hours treatment (Table 2), but there were no reported infections among patients treated with anakinra. There were no significant differences between treatment groups in the initial length of stay (4.5 days [anakinra], 4.0 days [placebo], P=0.80) or total hospital days during the 14-day period (5.0 days [anakinra], 6.0 days [placebo], P=0.65). Two patients in the anakinra group and 3 patients in the placebo group experienced worsening HF or readmission for HF (OR 0.61 [0.09-4.34], P=0.62). At 72 hours, patients treated with anakinra were numerically less likely to have pulmonary congestion, edema, S3 gallop, or JVD on exam, although only the effects on edema achieved statistical significance (21% vs 62%, OR 0.17 [0.03, 0.92], P=0.041). When these four markers of congestion were combined to form a composite score (0 – 4, based upon the presence of pulmonary congestion, edema, S3 gallop, JVD), patients receiving anakinra were more likely to experience a reduction in congestion at 72 hours, while patients receiving placebo did not experience any statistical difference at 72 hours follow-up (Supplemental Figure 1). These findings were evident despite no differences in total IV furosemide usage during the first 72 hours (anakinra: 280 [100, 490] mg; placebo: 440 [300, 560] mg, P=0.11).

In patients with paired baseline and day 14 echocardiograms (N=14), anakinra was associated with a greater recovery in LVEF (+10% [+3, +14]) compared to placebo (0 [−16%, +5%], P=0.020). There were no other significant differences in echocardiographic measures of LV volumes, transmitral flow and mitral annulus tissue Doppler spectra.

Discussion

The results of this study provide the first direct evidence that IL-1 drives the systemic inflammatory response during ADHF and suggests that targeted IL-1 blockade is sufficient to accelerate resolution of the acute inflammatory response. These conclusions derive primarily from the significant relative reductions in CRP and IL-6 versus placebo throughout the 14-day treatment course. Moreover, the current study demonstrates the preliminary feasibility of IL-1 blockade in ADHF, given that anakinra was generally well tolerated and associated with no significant increase in adverse events versus placebo. While these results are encouraging and provide incremental support for continued investigation of IL-1 blockade as a therapeutic strategy, it is important to note that this study was not designed to provide definitive answers of safety and/or efficacy from a treatment perspective. Instead, the study was designed to characterize the surrogate biomarkers of response to IL-1 blockade. All findings should therefore be considered “hypothesis-generating” for future confirmatory studies.

An area-under-the-curve approach was used to compare the inflammatory response throughout the 14-day treatment. While treatment with anakinra failed to reduce AUC0-3 or AUC0-14 for CRP using the absolute values, this analysis was highly influenced by baseline CRP and skewed by the fact that all four patients with baseline CRP >90 mg/L were randomly allocated to anakinra treatment. When normalized for baseline CRP values, treatment with anakinra produced a significant reduction in AUC for CRP that was evident at 72 hours and grew to become more pronounced at 14 days. It remains undetermined, however, whether alternative anakinra dosing regimens would provide additional CRP lowering effects. Given the plasma half-life of CRP (~18 hours), a pharmacologic strategy that completely inhibited all CRP production would be expected to reduce relative CRP concentration by >90% at 72 hours. The observed 61% relative reduction in CRP at 72 hours suggests (a) incomplete CRP blockade during the first 72 hours, (b) impaired CRP clearance resulting in a prolonged plasma half-life, or (c) non-IL-1 mediated production of CRP. In prior studies among patients with sepsis and stroke, anakinra was infused at doses as high as 2 mg/kg/hour (>2,000 mg/day) for up to 72 hours without any increase in adverse effects.22

In a prior study 108 HF patients, reduced LVEF (<35%) and elevated CRP (>2.97 mg/L) were the two strongest predictors of major adverse cardiovascular events (death, heart transplant, HF hospitalization).17 After 1 year, event-free survival was approximately 50% in patients with high CRP versus approximately 85% in patients with normal CRP (P=0.0003). More recently, a multivariate analysis of ADHF patients identified marked elevations in baseline CRP (>25 mg/L) as the strongest independent predictor of HF readmission.24 A proof-of-concept study among patients with chronic systolic HF and elevated CRP (>2 mg/L) observed a significant improvement in aerobic exercise performance (peak VO2 = 12.3 [baseline] to 15.1 [final] mL/kg/min, P=0.016) following 2 weeks treatment with anakinra and associated with >90% reduction in CRP.21 The ideal anti-inflammatory regimen may therefore need to address both the acute anti-inflammatory response accompanying decompensation and the residual low-grade inflammation that persists after discharge.

The current study also provides incremental evidence supporting the selectivity of IL-1 blockade to avoid significant effects on biomarkers of the innate immune response. IL-17A is an important mediator of chemokine production (along with interferon-γ [IFNγ]) to recruit monocytes and neutrophils to the site of tissue injury;22 TNFα is a potent mediator of systemic auto-immune function that often operates in parallel with IL-1 auto-inflammatory activity.22 However, previous studies pharmacologic suggest a deleterious effect following TNFα-blockade in chronic HF patients.25–27 Despite the fact that anakinra significantly blunted IL-6 and CRP (surrogate markers for IL-1 activity) in the current study, there were no detectable effects on IL-17 and TNFα throughout the 14-day treatment. These results corroborate findings from the previously mentioned proof-of-concept study in which anakinra produced profound CRP reductions (~90% versus baseline) without any measureable changes in TNFα or IFNγ.21

When examining the results of the placebo group, it is interesting to note that contemporary standard of care does little to affect the inflammatory response during the first 72 hours of treatment. This observation is consistent with a previous study of ADHF patients randomized to intravenous use of nesiritide versus nitroglycerin (Chow et al), in which inflammatory biomarkers (CRP, IL-6, TNFα, and TGFβ) remained elevated throughout the first 48 hours of admission regardless of treatment allocation. Despite the persistent inflammatory activity during the first 72 hours of the current study, the CRP signal at 14 days dropped to a median of 4.4 mg/L, which represented >80% reduction from baseline values. This observation suggests that the inflammatory response during the acute phase of HF decompensation may “wax and wane” in parallel to HF symptoms. It remains to be determined whether the incomplete resolution of inflammation at 14 days (among placebo-treated patients) represents a viable opportunity for intervention to improve patient outcomes. Ongoing studies of IL-1 blockade in ambulatory patients with recently decompensated HF or myocardial infarction will help to address this question.28–29

In addition to the relatively small sample size, a primary limitation to the current study was the loss to follow-up rate at 14 days. Given that follow-up rates were similar between treatment groups, it is unlikely that this stems from a treatment effect of anakinra and more likely reflects the real-world struggles of our patient population at an urban academic medical center. Socioeconomic status, healthcare literacy, and adherence to pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic regimens are well-described risk factors for HF admissions and likely contributed to the poor follow-up rate observed in this study.29

The use of limited transthoracic echocardiography also limited our ability to determine the mechanisms by which anakinra may have affected cardiac function. Future studies would benefit from a more thorough echocardiographic evaluation including assessment of global strain patterns and wall motion abnormalities.

Another limitation to the current study stems from the difficulty in standardizing “time from symptom onset” in ADHF patients. Unlike the symptoms of other acute conditions, such as acute myocardial infarction, the symptoms of HF often develop gradually over a series of days to weeks. While some patients may seek treatment early in the course of symptoms, others may put off seeking medical care for an extended period of time. As a result of these varying pre-hospital courses, it becomes difficult to ensure that all patients are receiving an experimental therapy at comparable points in their disease course. Indeed, this discrepancy may contribute to the considerable variation observed in baseline CRP. We attempted to partially correct for this variation by requiring that all patients complete the screening process—including CRP measurement—within the first 24 hours of hospitalization, and also by analyzing the CRP data after correction for the baseline levels. Given the stringent diagnostic criteria for ADHF, overlapping differential diagnoses among treating providers, and time required for patient screening, consent, and enrollment, this resulted in a median time of 21 hours from admission to first dose in the current study. While future studies may attempt to further standardize the “time from symptom onset” in ADHF patients, we believe that “time from admission” represents a more feasible treatment goal.

In summary, we report the results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in which 14 days of treatment with anakinra reduced the systemic inflammatory response among patients with ADHF. IL-1 blockade was well-tolerated by patients and not associated with any adverse clinical events. While the current study does not directly address whether inflammation plays a causal role in acute decompensation, it does provide a novel description of the inflammatory response throughout the course of admission, hospitalization, and discharge and provide confirmatory evidence that IL-1 mediates the IL-6 and CRP response during ADHF. These findings support the continued exploration of targeted anti-IL-1 strategies to determine whether modulation of the inflammatory response will improve clinical outcomes for HF patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Composite congestion scores at baseline and 72 hours among patients randomized to anakinra versus placebo. The composite score (range 0 – 4) was calculated based upon the presence of each of the following findings on physical exam: pulmonary congestion, edema, S3 gallop, jugular venous distension.

Table 3.

Adverse Events during treatment (14 days)

| Event | Anakinra | Placebo | OR (95% CI) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Worsening HF | 1 | 1 | 1.00 (0.056-17.75) |

1.00 |

| Readmission for HF | 1 | 2 | 0.46 (0.037-5.77) |

0.55 |

| Worsening HF or readmission for HF | 2 | 3 | 0.61 (0.085-4.37) |

0.62 |

| Readmission for any cause | 1 | 3 | 0.26 (0.023-2.85) |

0.27 |

| Acute Kidney Injury (KDIGO≥1) | 5 | 5 | 1.00 (0.21-4.69) |

1.00 |

| Infection | 0 | 2 | 0.17 (0.01-3.94) |

0.27 |

| Sepsis | 0 | 1 | 0.31 (0.012-8.29) |

0.48 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 0 | 1 | 0.31 (0.012-8.29) |

0.48 |

| Any Adverse Events (patients) | 7 (6) | 12 (10) | 0.33 (0.08-1.49) |

0.15 |

| Serious Adverse Events (patients) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 0.33 (0.049-2.27) |

0.26 |

Abbreviations: CI=Confidence Interval; HF=Heart Failure; KDIGO=Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; OR=Odds Ratio

Table 4.

Physical Exam Findings

| Event | Anakinra | Placebo | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Pulmonary Congestion | 8/14 (57%) | 8/14 (57%) | 1.00 |

| Edema | 11/14 (79%) | 12/14 (86%) | 0.62 |

| S3 gallop | 0/14 (0%) | 3/14 (21%) | 0.16 |

| JVD | 6/14 (43%) | 6/14 (43%) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| 72 hours/Discharge | |||

| Pulmonary Congestion | 4/14 (29%) | 4/13 (31%) | 0.91 |

| Edema | 3/14 (21%) | 8/13 (62%) | 0.041 |

| S3 gallop | 0/14 (0%) | 2/13 (15%) | 0.25 |

| JVD | 0/14 (0%) | 2/13 (15%) | 0.25 |

|

| |||

| 14 days | |||

| Pulmonary Congestion | 0/9 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | NA |

| Edema | 1/9 (11%) | 1/8 (12%) | 0.93 |

| S3 gallop | 0/9 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | NA |

| JVD | 0/9 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | NA |

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded an American Heart Association Beginning Grant-in-Aid to Dr. Van Tassell. The study was also supported in part by UL1TR000058 from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Science.

References

- 1.Weintraub NL, Collins SP, Pang PS, Levy PD, Anderson AS, Arslanian-Engoren C, Gibler WB, McCord JK, Parshall MB, Francis GS, Gheorghiade M. Acute heart failure syndromes: emergency department presentation, treatment, and disposition: current approaches and future aims: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:1975–96. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f9a223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Flintoft V, Lee DS, Lee H, Guyatt GH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing readmission rates and mortality rates in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2315–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.21.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keenan PS, Normand SL, Lin Z, Drye EE, Bhat KR, Ross JS, Schuur JD, Stauffer BD, Bernheim SM, Epstein AJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, Chen J, Federer JJ, Mattera JA, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Intravenous nesiritide vs nitroglycerin for treatment of decompensated congestive heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:1531–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.12.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binanay C, Califf RM, Hasselblad V, O’Connor CM, Shah MR, Sopko G, Stevenson LW, Francis GS, Leier CV, Miller LW. Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial. JAMA. 2005;294:1625–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.13.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleland JG, Coletta AP, Yassin A, Buga L, Torabi A, Clark AL. Clinical trials update from the European Society of Cardiology Meeting 2009: AAA, RELY, PROTECT, ACTIVE-I, European CRT survey, German pre-SCD II registry, and MADIT-CRT. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:1214–9. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleland JG, Freemantle N, Coletta AP, Clark AL. Clinical trials update from the American Heart Association: REPAIR-AMI, ASTAMI, JELIS, MEGA, REVIVE-II, SURVIVE, and PROACTIVE. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuffe MS, Califf RM, Adams KF, Jr, Benza R, Bourge R, Colucci WS, Massie BM, O’Connor CM, Pina I, Quigg R, Silver MA, Gheorghiade M. Short-term intravenous milrinone for acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:1541–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.12.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M, Burnett JC, Jr, Grinfeld L, Maggioni AP, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zannad F, Cook T, Ouyang J, Zimmer C, Orlandi C. Effects of oral tolvaptan in patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure: the EVEREST Outcome Trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1319–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMurray JJ, Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Bourge RC, Cleland JG, Jondeau G, Krum H, Metra M, O’Connor CM, Parker JD, Torre-Amione G, van Veldhuisen DJ, Lewsey J, Frey A, Rainisio M, Kobrin I. Effects of tezosentan on symptoms and clinical outcomes in patients with acute heart failure: the VERITAS randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;298:2009–19. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mebazaa A, Nieminen MS, Packer M, Cohen-Solal A, Kleber FX, Pocock SJ, Thakkar R, Padley RJ, Poder P, Kivikko M. Levosimendan vs dobutamine for patients with acute decompensated heart failure: the SURVIVE Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1883–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.17.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor CM, Starling RC, Hernandez AF, Armstrong PW, Dickstein K, Hasselblad V, Heizer GM, Komajda M, Massie BM, McMurray JJ, Nieminen MS, Reist CJ, Rouleau JL, Swedberg K, Adams KF, Jr, Anker SD, Atar D, Battler A, Botero R, Bohidar NR, Butler J, Clausell N, Corbalan R, Costanzo MR, Dahlstrom U, Deckelbaum LI, Diaz R, Dunlap ME, Ezekowitz JA, Feldman D, Felker GM, Fonarow GC, Gennevois D, Gottlieb SS, Hill JA, Hollander JE, Howlett JG, Hudson MP, Kociol RD, Krum H, Laucevicius A, Levy WC, Mendez GF, Metra M, Mittal S, Oh BH, Pereira NL, Ponikowski P, Tang WH, Tanomsup S, Teerlink JR, Triposkiadis F, Troughton RW, Voors AA, Whellan DJ, Zannad F, Califf RM. Effect of nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:32–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow SL, O’Barr SA, Peng J, Chew E, Pak F, Quist R, Patel P, Patterson JH, Heywood JT. Renal function and neurohormonal changes following intravenous infusions of nitroglycerin versus nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2011;17:181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Feldman AM, Young JB, White BG, Mann DL. Cytokines and cytokine receptors in advanced heart failure: an analysis of the cytokine database from the Vesnarinone trial (VEST) Circulation. 2001;103:2055–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.16.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long CS. The role of interleukin-1 in the failing heart. Heart Fail Rev. 2001;6:81–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1011428824771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin WH, Chen JW, Jen HL, Chiang MC, Huang WP, Feng AN, Young MS, Lin SJ. Independent prognostic value of elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2004;147:931–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Roubenoff R, Dinarello CA, Harris T, Benjamin EJ, Sawyer DB, Levy D, Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB. Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:1486–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057810.48709.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chow SL, O’Barr SA, Peng J, Chew E, Pak F, Quist R, Patel P, Patterson JH, Heywood JT. Modulation of novel cardiorenal and inflammatory biomarkers by intravenous nitroglycerin and nesiritide in acute decompensated heart failure: an exploratory study. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:450–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.958066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lourenco P, Paulo Araujo J, Paulo C, Mascarenhas J, Frioes F, Azevedo A, Bettencourt P. Higher C-reactive protein predicts worse prognosis in acute heart failure only in noninfected patients. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:708–14. doi: 10.1002/clc.20812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Tassell BW, Arena RA, Toldo S, Mezzaroma E, Azam T, Seropian IM, Shah K, Canada J, Voelkel NF, Dinarello CA, Abbate A. Enhanced Interleukin-1 activity contributes to exercise intolerance in patients with systolic heart failure. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood. 2011;117:3720–32.3083294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-273417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottdiener JS, Bednarz J, Devereux R, Gardin J, Klein A, Manning WJ, Morehead A, Kitzman D, Oh J, Quinones M, Schiller NB, Stein JH, Weissman NJ, American Society of Echocardiography American Society of Echocardiography recommendations for use of echocardiography in clinical trials. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004 Oct;17(10):1086–119. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eurlings LW, Sanders-van Wijk S, van Kimmenade R, Osinski A, van Helmond L, Vallinga M, Crijns HJ, van Dieijen-Visser MP, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Pinto YM. Multimarker Strategy for Short-Term Risk Assessment in Patients With Dyspnea in the Emergency Department: The MARKED (Multi mARKer Emergency Dyspnea)-Risk Score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1668–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung ES, Packer M, Lo KH, Fasanmade AA, Willerson JT. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure: results of the anti-TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart Failure (ATTACH) trial. Circulation. 2003;107:3133–40. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000077913.60364.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deswal A, Bozkurt B, Seta Y, Parilti-Eiswirth S, Hayes FA, Blosch C, Mann DL. Safety and efficacy of a soluble P75 tumor necrosis factor receptor (Enbrel, etanercept) in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 1999;99:3224–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.25.3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann DL, McMurray JJ, Packer M, Swedberg K, Borer JS, Colucci WS, Djian J, Drexler H, Feldman A, Kober L, Krum H, Liu P, Nieminen M, Tavazzi L, van Veldhuisen DJ, Waldenstrom A, Warren M, Westheim A, Zannad F, Fleming T. Targeted anticytokine therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the Randomized Etanercept Worldwide Evaluation (RENEWAL) Circulation. 2004;109:1594–602. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124490.27666.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Tassell BW, Valle Raleigh J, Oddi C, Carbone S, Canada J, et al. Interleukin-1 Blockade in Recently Decompensated Systolic Heart Failure: Study Design of the Recently Decompensated Heart Failure Anakinra Response Trial (RED-HART) J Clin Trial Cardiol. 2015;2(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridker PM, Thuren T, Zalewski A, Libby P. Interleukin-1β inhibition and the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events: rationale and design of the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS) Am Heart J. 2011 Oct;162(4):597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawkins NM, Jhund PS, McMurray JJ, Capewell S. Heart failure and socioeconomic status: accumulating evidence of inequality. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012 Feb;14(2):138–46. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Composite congestion scores at baseline and 72 hours among patients randomized to anakinra versus placebo. The composite score (range 0 – 4) was calculated based upon the presence of each of the following findings on physical exam: pulmonary congestion, edema, S3 gallop, jugular venous distension.