Abstract

Purpose of review

The term ‘patient engagement in research’ refers to patients and their surrogates undertaking roles in the research process beyond those of study participants. This paper proposes a new framework for describing patient engagement in research, based on analysis of 30 publications related to patient engagement.

Recent findings

Over the past 15 years, patients’ perspectives have been instrumental in broadening the scope of rheumatology research and outcome measurement, such as evaluating fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Recent reviews, however, highlight low-quality reporting of patient engagement in research. Until we have more detailed information about patient engagement in rheumatology research, our understanding of how patient perspectives are being integrated into research projects remains limited.

Summary

When authors follow our guidance on the important components for describing patients’ roles and function as ‘research partners,’ researchers and other knowledge users will better understand how patients’ perspectives were integrated in their research projects.

Keywords: Patient engagement in research, Patient participation, Patient involvement, Patient research partners

Introduction

Patient engagement in research refers to patients or their surrogates (e.g., informal caregivers) undertaking roles in the research process beyond the roles of study participants. This practice contributes to a patient perspective being represented in the research process.

Patient engagement in research is increasingly recognized as being one way to enhance the relevance, quality, and acceptability of research to advance healthcare policies and practices [1,2]. Some countries [3–6] have instituted legislation, policies, and funding mechanisms [6–8] to actively encourage patient engagement in the research process [1,5,7,9]. For example, in the United States, the nongovernmental organization PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute), founded in 2010, offers funding for research projects that meet specific requirements regarding patient engagement in the research teams.

Patient engagement in research has been growing gradually in the field of rheumatology over the last 15 years [10]. The Canadian Arthritis Network (CAN) and Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) were two early adopters of this practice and both have contributed to its development [11,12]. CAN, which operated from 1998 to 2014, required all the research teams it funded to include patients [12]. Its governing board included a patient, each grant application was reviewed by at least two patients, and each topic at its scientific meetings required at least one patient to provide his/her perspective [12]. OMERACT, founded in 1992, is an international organization of rheumatology experts seeking to use a data-driven consensus process to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology [13]. In 2000, OMERACT recognized the need for a patient perspective in order to determine the smallest quantifiable change that was clinically meaningful for certain domains of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [10]. Consequently, patients have been involved in OMERACT since its 6th biennial meeting in 2002, and their perspectives resulted in the research agenda being immediately widened to include well-being, fatigue, and sleep patterns as important domains of RA that were currently ignored or under-represented in outcome measures of RA [10,14]. One example is the OMERACT Fatigue Working Group in which patients engaged in the development of a patient-reported outcome measure for fatigue: the Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue (BRAF) questionnaire [10]. Another example is a 2011 systematic review that reported that the integration of the patient perspective in the creation of domains and outcome measures of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was limited [15]. The OMERACT PsA Working Group subsequently updated a core domain set for PsA for randomized controlled trials and longitudinal observational studies, and outcome measures for assessing PsA are currently under development [16].

The rheumatology research community has not only engaged with patients in research, but has also published a model and recommendations to support patient-researcher collaborations in research. Hewlett et al. [17] used their experience as patients and researchers collaborating in research through OMERACT to develop the FIRST (Facilitate, Identify, Respect, Support, and Train) model as a practical guide for engagement of patients in research [17,18]. In 2011, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) published recommendations for patient engagement in research projects [19]. Similar recommendations were approved by OMERACT and published in 2016 [20]. Both OMERACT’s and EULAR’s policies now state that at least two patients should be engaged in every research project and initiative [21]. These policies could be an indication of a positive impact of patient engagement in rheumatology research to better meet the healthcare needs and preferences of patients.

However, evidence substantiating the positive impact of patient engagement in research is limited [2,22,23]. Reviews published in the last five years on the impacts of and barriers to patient engagement in research highlighted a lack of consistent language, preferred methods, outcome measures, evidence of impact, and quality of reporting of patient engagement in research [2,23–25]. It has therefore been recommended that best practice approaches be developed for including, measuring, and reporting patient engagement in research [2,23–25]. In 2011, the GRIPP (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and Public) checklist was developed to guide the reporting of results from studies on the impact of patient and public engagement in research [26]. However, it does not fully address the issue of low-quality reporting of patient engagement in research [22]—possibly because it was developed specifically for reporting empirical studies focusing on the impact of patient engagement in research [26]—and does not provide the language for promoting consistent and inclusive reporting of patient engagement in research [26].

The current evidence base is limited regarding how patients are being engaged in rheumatology research. Often, the description of patient engagement is incomplete and lacks adequate information to provide a clear picture of how a patient perspective was integrated into the research process. To address this, we sought to create a framework that includes the components and language authors could use when reporting patient engagement in rheumatology research projects [22,27]. Throughout this paper, we use the term Patient Research Partner (PRP) to describe patients, their family members, and informal caregivers who engage in health research projects [8].

Methods

Our research team used a researcher-initiated collaboration approach via email communication with an adult patient and knowledge translation specialist with RA (AMH) from an Arthritis Patient Advisory Board. During disseminating our results, she reviewed and provided input on multiple drafts and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework [28], we used an iterative process to formulate the research question/objective, identify and select publications, and chart, analyze, and summarize the data [28]. Publications were initially identified from a search of six electronic databases (EMBASE, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Conference Papers Index) in July 2015. The search strategy combined five sets of search terms: 1) patient, consumer, public, user, and similar nouns denoting PRPs; 2) biomedical research, clinical research, health services research, and other terms denoting health research; 3) patient advocacy, consult, collaborat*, partner, and other terms denoting PRPs’ roles; 4) concept, opinion, viewpoint, and other term denoting conceptualization; and 5) the terms model and framework. We included English-language publications from 1980 to 2015 that contained models or frameworks relevant to categorizing patient engagement in research. We excluded publications with models and frameworks not related to patient engagement in research. A subsequent search was conducted in September 2016 with no limits set for publication date. Publications were identified from Google using three search terms ‘patient engagement/involvement/participation in research’, reference lists of included publications, and four key journals (Health Expectations, Research Involvement and Engagement, Patient Experience Journal, and Journal of Participatory Medicine) that specialize in publishing on patient engagement. This additional search led to the inclusion of more models, frameworks, guidelines, reviews, and an empirical study.

The first author (CBH) screened the titles, abstract, and full text of the publications for inclusion, and selected those that provided descriptors related to the context and process of patient engagement in research. Context refers to the conditions under which engagement occur [25,26]. Process refers to the methods of engaging patients in the research process [26]. Finally, we excluded publications without content corresponding to any of three deductive categories indicated below.

Charting, Analyzing, and Summarizing the Data

We conducted a directed content analysis using three mutually exclusive categories that were selected based on a preliminary review of five papers on patients’ engagement in research [2,22,23,27,29]:

Who (Who are the PRPs?)

How (How do PRPs engage in research?)

When (When during a research project do PRPs engage?)

The nuances in each category were then identified as descriptors. Where appropriate, the descriptors were clustered into a subcategory. The descriptors were iteratively revised to capture newly emerging information. Preference was given to labeling the descriptors with terms identified in the publications, but additional terms were introduced in the absence of appropriate descriptors. We discussed and provided an example of how these descriptors can be used in the reporting of patient engagement in research projects in scientific papers.

Results

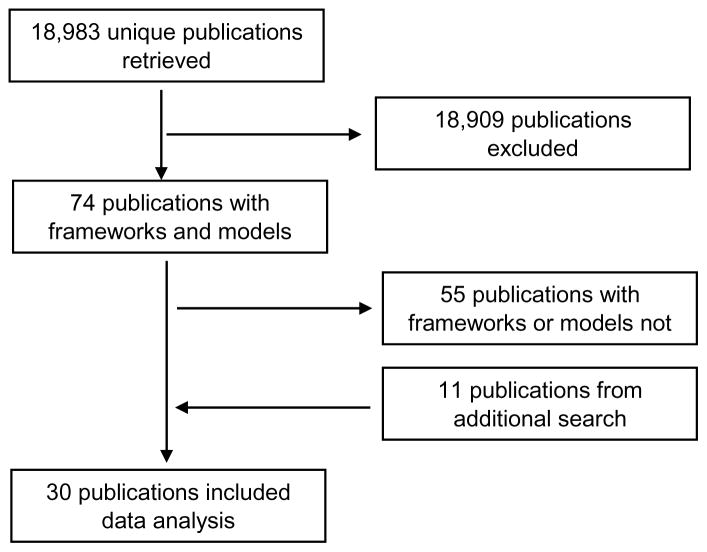

Of the 18,983 unique publications retrieved, 19 were included from the initial literature search and 11 from the subsequent search (Figure 1). Of the 30 publications that were retained, 24 contained models and frameworks (Table 1). The publications focused on patient and public engagement in research or on public engagement. Most of the publications had a first author from the UK (n = 11) or the USA (n = 13). With the exception of one paper that was published in 1969, all the papers were published between 1992 and 2016. The 1969 publication [30] is a seminal paper on the levels of non-participation through to participation of citizens in decision-making in governmental social plans and programs, and is therefore a key paper on engagement level. Data analysis yielded six subcategories of descriptors: Type of Affiliation, PRP Characteristics, Initiation of Engagement, Method of Contribution, Level of Engagement, and Stages of Research Cycle (Table 2). Among the 24 publications with models and frameworks, the subcategory ‘Level of engagement’ appeared most frequently (n = 19) and ‘PRP characteristics’ appeared least frequently (n = 5) [25,27]. The following paragraphs outline the proposed framework arranged according to the three main categories: Who, How, and When.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of publication search and selection process

Table 1a.

Publications reviewed and their subcategory contribution (reviews with models and frameworks)

| Author | Country of First-Author | Informative Component | Category | Subcategory Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnstein (1969)[30] | USA | Ladder of citizen participation | Who | Type of Affiliation |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| Hart (1992)[31] | The ladder of participation | How | Initiation of Engagement Level of Engagement |

|

| Hickey (1996)[4] | UK | Participation continuum | How | Type of Affiliation Level of Engagement |

| Liberty (1999)[32] | New Zealand | Decision-making models in research | How | Initiation of Engagement Level of Engagement |

| Boote (2002)[33] | UK | Levels of consumer involvement in health research | How | Level of Engagement |

| Rowe 2005)[34] | UK |

|

Who | Type of Affiliation |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| Hewlett (2006)[17] | UK | FIRST Model | Who | Type of Affiliation |

| How | Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| When | Stages of Research Cycle | |||

| IAP2 (2007)[35] | USA | Spectrum of public participation | How | Level of Engagement |

| Oliver (2008)[29] | UK | Framework for describing involvement in research agenda setting | Who | Type of Affiliation |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| Tritter (2009)[3] | UK |

|

Who | PRP Characteristics |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| Venuta (2010)[5] | Canada | CIHR’s model for sustained citizen engagement | When | Stages of Research Cycle |

| Staniszewska (2011)[26] | UK | The complexity of PPI impact evaluation | Who | PRP Characteristics |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| Anderson (2012)[36] | USA | Examples of models of engagement and communication for patient centric initiatives | How | Method of Contribution |

| Brett (2012)[2] | UK | Affects of Context and Process on impact of patient and public involvement in research | Who | Type of Affiliation |

| How | Level of Engagement | |||

| When | Stages of Research Cycle | |||

| Deverka (2012)[37] | USA | Conceptual model for stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness research | Who | PRP Characteristics |

| How | Level of Engagement | |||

| Hayes (2012)[6] | UK | Briefing notes for researchers | Who | Type of Affiliation |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Level of Engagement |

|||

| When | Stages of Research Cycle | |||

| De Wit (2013)[18] | Netherlands | FIRST Model (revised) | Who | PRP Characteristics |

| How | Level of Engagement | |||

| Shippee (2013)[24] | USA |

|

How | Initiation of Engagement Level of Engagement |

| When | Stages of Research Cycle | |||

| Travers (2013)[38] | Canada | A model of research centered on community control and ownership | Who | PRP Characteristics |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Level of Engagement |

|||

| When | Stages of Research Cycle | |||

| Brookman-Frazee (2015)[39] | USA | Model of research community partnerships | How | Initiation of Engagement |

| Frank (2015)[1] | USA | Conceptual model of patient-centered outcomes research | How | Method of Contribution |

| Oliver (2015)[40] | UK | Framework for public involvement in research: multiple drivers, process and impacts | Who | Type of Affiliation |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| PCORI (2015)[41] | USA | Sample Model addressing Fair Compensation for Engaged Research Partners: Engagement Spectrum With Examples: An ideal Moving Toward Greater Collaboration | How | Level of Engagement |

| Johnson (2016)[42] | USA | A model of patient engagement to support patient partnerships with researchers | How | Type of Affiliation |

Table 2.

Components and descriptors for reporting patient engagement in rheumatology research

| Who? | How? | When? |

|---|---|---|

Type of Affiliation

|

Initiation of Engagement

|

Stages of Research Cycle Preparatory Phase

|

1. Who are the patient research partners?

This category describes the PRPs who engaged in the research project. The Who category contains two subcategories of descriptors: Type of affiliation and PRP characteristics.

Type of Affiliation describes PRPs’ association with a research project and includes whether Individuals or Organized groups of PRPs were engaged in the research process and the type of research group that conducted the research [3,17,27,29,43]. Authors should specify if PRPs were engaged as individuals or as members of an organized group such as an advocacy group. A single representative from an organized group is considered an individual. The type of research group that conducted the research project should be specified, such as being a Research team, Advisory group, Steering committee, Working group, Focus group, or Expert panel [17,25,42,43].

PRP Characteristics refer to the research-relevant demographic and health characteristics of the PRPs. This subcategory allows authors to give further context about the basis of a patient perspective [22,25]. Authors should report the type of PRPs—whether they were patients, informal caregivers, or family members. The subcategory PRP characteristics includes the number of PRPs, the diagnosis and health-related issues, whether they are children or adults (e.g., young adults or seniors), their gender, and their race/ethnicity as appropriate for the research project being reported [38,44]. Reporting other personal characteristics of PRPs is not required, but could be valuable (e.g., PRPs’ experience with the rheumatologic disease(s) studied) [17,18].

2. How do patient research partners engage?

This category describes the roles of PRPs and the process through which they contribute to a research project. It has three subcategories of descriptors: Initiation of Engagement, Method of Contribution, and Level of Engagement.

Initiation of Engagement describes how PRPs were introduced into a research project. It highlights the idea that who initiates the research is an important factor because it shapes how the results are viewed by knowledge users [29]. This subcategory includes PRP-initiated, Researcher-initiated, or Jointly-initiated [24,25,29,32,36,38–40]. The descriptor PRP-initiated was informed by a reference in the literature to “child-initiated shared decision with adults” and “adult-initiated shared decision with children” to describe the extent of children’s roles when engaging in research-related activities [31]. Researcher-initiated engagement of PRPs can be observed in the patient-researcher collaborative research project that developed the FIRST model [17]. Jointly-initiated refers to situations where patients and researchers initiate a new research project together [39].

Method of Contribution refers to the media through which a patient perspective is included in the research. This subcategory includes six descriptors: Complete interviews/surveys, Participate in discussions, Participate in research-related tasks, Participate in face-to-face meetings, Participate virtually (e.g., by video, chat room, or email), and Participate by phone [6,23,27,29,34,40,43]. Authors can report engagement through a combination of these methods. Interviews and surveys are used to elicit information from PRPs. Discussions entail the exchange of ideas about the research project among the engaged PRPs and stakeholders, but do not necessarily involve reaching a decision about it. Participate in research-related tasks refers to the tasks beyond communicating with other members of the research group that PRPs undertake as contributions to the research project. It is the author’s responsibility to specify the important research-related tasks conducted by PRPs. Tasks conducted could include, for example, reviewing study documents, writing manuscripts, and presenting at scientific conferences. The contribution of PRPs may take place in-person (face-to-face), or virtually (e.g., video, chat room, or email) or by phone [27,34]. Method of contribution is not limited to real-time interactions. It includes delayed communication modes such as emails [29].

Level of Engagement is defined as the depth of PRPs’ involvement in the research group’s decision-making process. We specify four levels of engagement: Informed, Consulted, Collaborated, and Led [41]. The level to which PRPs engage is based on the flow of information during team communication sessions and the roles of the PRPs in deciding what information to use and how activities are to be conducted [32–34,36]. These factors reflect the distribution of control over information-use in research projects among the stakeholders engaged in it [4,32–34,36].

The first level, informed, describes when a PRP is given information about the research project as it develops [4,30,31,34,35,37,41]. Informed covers one-way flow of information from the other engaged stakeholders to the PRPs, with no reciprocation of information from the PRPs [4,30,34,35,37]. The second level, consulted, describes when information is solicited from PRPs to inform decision-making in research [4,6,25,29,30,33,35,37,41,44]. In this situation, the PRPs do not occupy the decision-making role that provides the discretion for them to decide how their contributions will be used [4]. There might have been no commitment from the researcher(s) to use the PRPs’ contributions or to provide feedback on how they were used by the research group [33]. Nevertheless, their contributions could have still influenced the decision-making. There are therefore two types of consultation: one in which PRPs receive feedback on their contributions and one in which they do not [31].

The third level is collaborated, in which there was two-way communication between the PRPs and other stakeholders [4,25,29,30,32,34,35,37,41,44]. During a collaboration, authority over decision-making and ‘authority of knowledge’ are continuously shared between the PRPs and other stakeholders [32]. The PRPs sometimes act as co-researchers [20] to provide alternative options and collaborate on decision-making during the research process [4,25,29,30,32,34,35,37, 44].

The fourth level is led. In this case, PRPs have the authority to make final decisions about the use of information and undertaking tasks during the research project [4,29–30,33,35–38,41,44]. Patient-led (or patient-directed) research can take different forms that are distinguished based on the distribution of the authority among the engaged stakeholders overseeing the research. These forms are delegated-led, fully-led, or co-led [30]. When delegated-led by a PRP, the PRP is assigned authority over decision-making for aspects of the research process, but executive power over the overall research process could still rest with other stakeholders [30]. When fully-led by a PRP, the researchers are usually the ones invited to engage in the research project, and the PRP has the final decision-making role [4,29,38]. When co-led by a PRP, the PRP has shared control of a research project [27,32]. When multiple PRPs are engaged in a research project, they might have varying levels of engagement. For example, a patient-led research project could include consulting with patients who are not part of the project team.

3. When do patient research partners engage?

This category describes the different points along the continuum of the process of a research project. It has one subcategory, the stages of research cycle. Our literature review found articles describing varying number of stages of a research cycle, which we summarize as seven stages (Table 2) [2,5,6,23–25]. Two systematic reviews summarised them into three phases: Preparatory, Execution, and Translation (Table 2) [23,24]. We recommend that whenever possible, authors should specify the stages of the research cycle in which PRPs engaged, but to be concise authors could report only the phase if PRPs were engaged in all the stages of the specified research phase.

The preparatory phase includes Identifying and prioritizing research questions and Acquiring funding [2,6,23,24]. Identifying and prioritizing research covers conceiving the research idea and formulating the pertinent research questions. Acquiring funding covers activities involved in the preparation and submission of a research proposal for funding [5,6,24]. The execution phase involves another two stages: Designing research and Undertaking research, which both involve developing and executing the research protocol [6,23,24]. Designing research entails deciding on the content of the research protocol, such as the recruitment process and the selection of outcome measures. Here PRPs could have played many important roles. As collaborators, they could have, for example, informed the recruitment strategy, selection of appropriate follow-up periods, and methods of communicating with participants. Undertaking the research entails working with the research team to carry out participant recruitment, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation [2,24]. Finally, the translation phase has three stages: Disseminating, Implementing, and Evaluating impact of the study results [6,23,24]. Disseminating is the planned dispersion of the knowledge constructed through the research to target audiences, and sometimes further communication to facilitate its application [45]. Disseminating research involves study write-up, its publication and presentation, and other activities that make the knowledge available to others to use and increase awareness of its existence. Implementing is a context-specific process that enables routine use of research findings, such as a research-based intervention (e.g., policy, program, or practice) to improve healthcare [46]. Evaluating impact covers purposeful monitoring and assessing the extent to which the research findings have been accessed and used [47].

Application of the Framework

We named it the Patient Engagement in Research Description (PED) Framework. When using the PED Framework, authors should cover as many of the six subcategories as possible and apply the descriptors to provide details in the descriptions of patient engagement in their research project. Below we use an excerpt from a published study on a decision aid for people with rheumatoid arthritis to explain how the framework could be applied.

In the paper by Li et al. [48], they described how patients were engaged in their project as follows, “Development of the ANSWER was guided by the International Patient Decision Aids Standards, our qualitative study on the help-seeking experience of patients with early RA, and input from patient/consumer collaborators” (p.1473) [48].

Using our framework of descriptors, we were able to highlight more relevant information, gathered from the original author (LCL), on the nature of patient engagement in this project: “In this study, we collaborated with three PRPs, including two women with RA and one man with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. PRPs were consulted for their perspectives primarily through in-person meetings. During the development of ANSWER, the PRPs participated in the design, production, and prototyping with the researchers and digital media students. They were also key members in the funding acquisition, as well as research design and execution of the subsequent proof-of-concept study. Furthermore, the PRPs played a key role in disseminating the findings through their contacts at The Arthritis Research Canada’s Arthritis Patient Advisory Board and Arthritis Consumer Experts.”

This one example demonstrates that without reporting on all components of the framework, a knowledge user will not have a good understanding of how a patient perspective contributed to the findings of a research project. Lack of details, however, does not negate the validity of the findings.

Discussion

This study developed a framework of descriptors for reporting the context and process of patient engagement in rheumatology research and was informed by a review of the literature related to patient engagement in research. The proposed subcategories and their corresponding descriptors are situated across three overarching categories: the Who, How, and When of patient engagement in research. The subcategories are components of patient engagement in research on which to report, and the descriptors are recommended language to provide an overview of the details about the roles and functions of the PRPs. The descriptors can be used to provide a concise and inclusive picture of PRPs’ engagement in a rheumatology research project. While we recommend that authors use the descriptors provided, authors are free to use other forms of the terms, such as patient-directed instead of patient-led, or participate by email instead of virtually.

Our framework complements and extends the recommendations of the GRIPP checklist and an existing framework for reporting patient engagement in research [24,26]. The GRIPP checklist is a guide for reporting the results of patients’ engagement in research for the purpose of future evaluation of its impact [26]. Our framework provides authors with the components of patient engagement in research to report on and the language to use. The framework by Shippee et al. [24] provides specific language for describing the initiation of engagement, level of engagement, and stages of the research cycle, all of which are considered important components of patient and public engagement in research. Shippee et al.’s framework reduced the level of engagement to a spectrum with two endpoints, ‘passive’ to ‘engaged,’ and gave no definitive description of those endpoints [24], which oversimplifies the assessment of level of engagement. Their framework “provides a standard structure and language for reporting and indexing to support comparative effectiveness [research] and optimize PSUE [(patient and service user engagement)]” (p.1152) [24]. The additional components we provide expand on their framework for describing the PRPs who were engaged and how they were engaged. Reporting details in the description of PRPs’ engagement provides knowledge users with adequate information to interpret the context and process of patient engagement in research. For example, one could reasonably speculate that a knowledge user would view a collaboration between researchers and patients with RA in a study on RA more favorably than a collaboration between researchers and patients with gout in a study on RA, even though both RA and gout are forms of arthritis. Our recommendations for reporting how PRPs were engaged will allow authors to convey specific details about the PRPs’ role and the rigor of their contributions, consequently strengthening the credibility of the study’s patient perspective and rendering the results more acceptable.

The PED Framework is one of the few to outline components and language for reporting patient engagement in research. We acknowledge, however, that it does not cover all the possible descriptors in each category. Furthermore, we emphasize reporting on the six components of the framework rather than adhering strictly to the specified forms of the descriptors to allow for the use of synonyms and different parts of speech. Overall, the present study contributes to the ongoing discussion on understanding, practicing, and evaluating patient engagement in research.

The framework is limited by not having been reviewed by an expert panel or otherwise peer-reviewed [28]. We would like to invite feedback about this framework and how it could be useful for strengthening the reporting of patient engagement in rheumatology research.

Conclusions

The PED Framework provides components with corresponding descriptors to support authors’ inclusive reporting of the context-specific contributions of PRPs in rheumatology research projects. We anticipate that use of this framework will facilitate reporting details of patient engagement in research, including in the rheumatology field. The more inclusive reports will provide a clear sense of how patient perspectives contributed to health research.

Table 1b.

Publications reviewed and their subcategory contribution (reviews without model or framework)

| Author | Country of First-Author | Informative Component | Category | Subcategory Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nilsen (2006)[43] | General body of article | Who | Type of Affiliation PRP Characteristics |

|

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| Hubbard (2008)[44] | UK | Involving people affected by cancer in research: a review of literature | Who | PRP Characteristics |

| How | Level of Engagement | |||

| Forsythe (2014)[25] | USA | A systematic review of approaches for engaging patients for research on rare diseases | Who | Type of Affiliation PRP Characteristics |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| When | Stages of Research Cycle | |||

| Domecq (2014)[23] | USA | Methods and phases of engagement | Who | Type of Affiliation PRP Characteristics |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution |

|||

| When | Stages of Research Cycle | |||

| Esmail (2015)[22] | USA | Table 1. Context and process measures | How | PRP Characteristics |

Table 1c.

Publications reviewed and their subcategory contribution (empirical study of primary data)

| Author | Country of Corresponding Author | Informative Component | Category | Subcategory Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forsythe (2015) [27] | USA | Methods, result, and discussion sections | Who | Type of Affiliation PRP Characteristics |

| How | Initiation of Engagement Method of Contribution Level of Engagement |

|||

| When | Stages of Research Cycle |

Acknowledgments

CBH is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. We thank Bao Chau Tran for her assistance with the literature search.

Footnotes

POST PRINT: Hamilton CB, Leese JC, Hoens AM, Li LC. Framework for Advancing the Reporting of Patient Engagement in Rheumatology Research Projects. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017 Jul;19(7):38. doi:10.1007/s11926-017-0666-4.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11926-017-0666-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, Schrandt S, Sheridan S, Gerson J, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1033–41. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0893-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2014:17. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tritter JQ. Revolution or evolution: the challenges of conceptualizing patient and public involvement in a consumerist world. Health Expect. 2009;12:275–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickey G, Kipping C. Exploring the concept of user involvement in mental health through a participation continuum. J Clin Nurs. 1998;7:83–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1998.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venuta R, Graham ID. Involving citizens and patients in health research. J Ambul Care Manage. 2010;33:215–22. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181e62bd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes HBS, Tarpey M. Briefing notes for researchers: Public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. Eastleigh: INVOLVE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.CIHR. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research - Patient Engagement Framework. Canadian Institutes of Health Research; [Accessed 30 Sep 2016]. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/spor_framework-en.pdf. Updated February 7, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hilliard TS, Paez KA. The PCORI Engagement Rubric: Promising Practices for Partnering in Research. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:165–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHMRC. A Model Framework for Consumer and Community Participation in Health and Medical Research. Commonwealth of Australia; Canaberra: 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10•.de Wit M, Kirwan JR, Tugwell P, Beaton D, Boers M, Brooks P, et al. Successful Stepwise Development of Patient Research Partnership: 14 Years’ Experience of Actions and Consequences in Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Patient. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0198-4. Provides an overview of the long-term engagement of patient research partners in OMERACT’s conferences and working groups and the impact of that engagement. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Wit MP, Abma TA, Koelewijn-van Loon MS, Collins S, Kirwan J. What has been the effect on trial outcome assessments of a decade of patient participation in OMERACT? J Rheumatol. 2014;41(1):177–84. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CAN. Canadian Arthritis Network - Legacy Report. Canadian Arthritis Network; 2014. [Accessed 16 Mar 2017]. http://can.arthritisalliance.ca/images/pdf/english-can-legacy-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, Idzerda L. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirwan J, Heiberg T, Hewlett S, Hughes R, Kvien T, Ahlmèn M, et al. Outcomes from the Patient Perspective Workshop at OMERACT 6. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:868–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tillett W, Adebajo A, Brooke M, Campbell W, Coates LC, FitzGerald O, et al. Patient Involvement in Outcome Measures for Psoriatic Arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16:418. doi: 10.1007/s11926-014-0418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease PJ, Callis Duffin K, Elmamoun M, Tillett W, et al. Updating the Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA) Core Domain Set: A Report from the PsA Workshop at OMERACT 2016. J Rheumatol. 2017 doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hewlett S, Wit M, Richards P, Quest E, Hughes R, Heiberg T, et al. Patients and professionals as research partners: challenges, practicalities, and benefits. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:676–80. doi: 10.1002/art.22091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Wit MP, Elberse JE, Broerse JE, Abma TA. Do not forget the professional--the value of the FIRST model for guiding the structural involvement of patients in rheumatology research. Health Expect. 2015;18:489–503. doi: 10.1111/hex.12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Wit MP, Berlo SE, Aanerud G-J, Aletaha D, Bijlsma J, Croucher L, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the inclusion of patient representatives in scientific projects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.135129. annrheumdis135129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung PP, de Wit M, Bingham CO, Kirwan JR, Leong A, March LM, et al. Recommendations for the involvement of patient research partners (PRP) in OMERACT working groups. A report from the OMERACT 2014 Working Group on PRP. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:187–93. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Heijde D, Aletaha D, Carmona L, Edwards CJ, Kvien TK, Kouloumas M, et al. 2014 Update of the EULAR standardised operating procedures for EULAR-endorsed recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:8–13. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4:133–45. doi: 10.2217/cer.14.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24••.Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, Wang Z, Elraiyah TA, Nabhan M, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2015;18:1151–66. doi: 10.1111/hex.12090. Proposes a two-part framework for reporting and indexing of patient and service user engagement (PSUE) that would support comparative effectiveness research on PSUE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25••.Forsythe LP, Szydlowski V, Murad MH, Ip S, Wang Z, Elraiyah TA, et al. A systematic review of approaches for engaging patients for research on rare diseases. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 3):S788–800. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2895-9. Systematic review of patient and stakeholder engagement in research on research diseases. It focused on the level of details used when describing engagement activities in the included studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Mockford C, Barber R. The GRIPP checklist: strengthening the quality of patient and public involvement reporting in research. IntJ Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(4):391–9. doi: 10.1017/s0266462311000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, Sabharwal R, Rein A, Konopka K, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: Description and lessons learned. J Gen Inter Med. 2016;31:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19– 32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliver SR, Rees RW, Clarke-Jones L, Milne R, Oakley AR, Gabbay J, et al. A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Expect. 2008;11:72–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnstein SR. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J Am Inst Plan. 1969;35:216–24. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart R. From Tokenism to Citizenship’. UNICEF International Child Development Centre; Florence: 1992. Innocenti Essays no 4: Children’s Participation. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberty KA, Laver A, Sabatino D. Collaborative partnerships in evaluation and experimental rehabilitation research. Int J Rehabil Res. 1999;22:283–90. doi: 10.1097/00004356-199912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boote J, Telford R, Cooper C. Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy. 2002;61:213–36. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowe G, Frewer LJ. A Typology of Public Engagement Mechanisms. Science, Technology & Human Values. 2005;30:251–90. doi: 10.1177/0162243904271724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.International Association for Public Participation. [Accessed 30 Sep 2016];IAP2 spectrum of public participation. 2007 http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/foundations_course/IAP2_P2_Spectrum_FINAL.pdf.

- 36.Anderson N, Bragg C, Hartzler A, Edwards K. Participant-Centric Initiatives: Tools to Facilitate Engagement In Research. Appl Transl Genomics. 2012;1:25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atg.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, Esmail LC, Ramsey SD, Veenstra DL, et al. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: defining a framework for effective engagement. J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1:181–94. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Travers R, Pyne J, Bauer G, Munro L, Giambrone B, Hammond R, et al. ‘Community control’ in CBPR: Challenges experienced and questions raised from the Trans PULSE project. Act Res. 2013;11:403–22. doi: 10.1177/1476750313507093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brookman-Frazee L, Stahmer A, Stadnick N, Chlebowski C, Herschell A, Garland AF. Characterizing the Use of Research-Community Partnerships in Studies of Evidence-Based Interventions in Children’s Community Services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:93–104. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0622-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oliver S, Liabo K, Stewart R, Rees R. Public involvement in research: making sense of the diversity. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20:45–51. doi: 10.1177/1355819614551848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.PCORI. Financial compensation of patients, caregivers, and patient/caregiver organizations engaged in PCORI-funded research as engaged research partners. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; 2015. [Accessed 30 Sep 2016]. http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Compensation-Framework-for-Engaged-Research-Partners.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson DS, Bush MT, Brandzel S, Wernli KJ. The patient voice in research—evolution of a role. Research Involvement and Engagement. 2016;2:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s40900-016-0020-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004563.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hubbard G, Kidd L, Donaghy E. Involving people affected by cancer in research: a review of literature. Eur J Cancer Care. 2008;17:233–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson PM, Petticrew M, Calnan MW, Nazareth I. Disseminating research findings: what should researchers do? A systematic scoping review of conceptual frameworks. Implement Sci. 2010;5:91. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penfield T, Baker MJ, Scoble R, Wykes MC. Assessment, evaluations, and definitions of research impact: A review. ResEval. 2014;23:21–32. doi: 10.1093/reseval/rvt021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li LC, Adam PM, Backman CL, Lineker S, Jones CA, Lacaille D, et al. Proof-of-Concept Study of a Web-Based Methotrexate Decision Aid for Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1472–81. doi: 10.1002/acr.22319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]