Abstract

Objectives

Real-world practices and attitudes regarding quantitative measurement of RA have received limited attention.

Methods

An email survey asked U.S. rheumatologist to self-report on their use of quantitative measurements (‘metric’).

Results

Among 493 respondents, metric rheumatologists (58%) were more likely to be in group practice and use TNFi. HAQ (35.5%) and RAPID3 (27.1%) were most commonly measured. Reasons for not measuring included: too time-consuming and not available electronically. Based on simulated case scenarios, providing more quantitative information increased the likelihood to change DMARDs/biologics.

Conclusion

Routine use of quantitative measurement for U.S. RA patients is increasing over time but remains low.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, survey, rheumatology, epidemiology, treat to target, DAS28, RAPID3, CDAI, measurement, patient reported outcomes

Introduction

Treat-to-target (T2T), a strategy advocated by international rheumatology guidelines, entails the use of quantitative disease activity measures to facilitate managing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (1–3). While there seemingly was consensus during the processes used to establish these guidelines, attitudes and actual practices of U.S. rheumatologists about T2T and quantitative assessment are difficult to ascertain. Disease registries are generally not helpful to inform the question about how often rheumatologists collect quantitative arthritis measures since such measurement is a required feature and strength of most physician-based registries. In this study, we report results from a survey of U.S. rheumatologists regarding attitudes, practices, and behaviors about quantitative assessment in RA.

Methods

Participant Selection

A convenience sample of U.S. rheumatologists was invited by email in 2014 to participate in an online survey focused on RA management attitudes and treatment patterns. Rheumatologists were identified using a custom database maintained by the authors (JC) over the last decade, curated from personal contacts and collaborations. As part of the invitation, rheumatologists were randomized to receive $0, $20, or $40. The survey took approximately 10 minutes; consent was implied conditional on participation. For those not initially responding, a reminder was emailed one month later; individuals were re-randomized to be offered the same incentive or $20 more.

Survey Content

The 26 question survey solicited information regarding use of quantitative measurement in RA and related attitudes. Rheumatologists were classified as ‘metric’ physicians (the main independent variable) if they self-reported that they “formally collected a disease-specific activity measure (e.g. CDAI, HAQ) at every visit in RA patients”. The survey also presented three simulated patient case scenarios to ascertain if metric vs. non-metric physicians approached RA management similarly. These three cases described comparable patients, all with moderate disease activity, but provided varying amounts of quantitative information. For each case, physicians were asked whether they would escalate RA treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Responses from physicians no longer in practice (e.g. retired, employed by industry) were excluded. Descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regression was used to compare characteristics of metric vs. non-metric physicians. Survey responses were compared with two similar surveys deployed in 2008 and 2005(5). While the same source population was surveyed for each, not all physicians remained eligible over time; therefore, results were described as three serial cross-sectional surveys. Data from the three scenarios was analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to evaluate the likelihood of treatment escalation, accounting for the clustered nature of the data. The study was governed by the local IRB.

Results

Characteristics of survey respondents

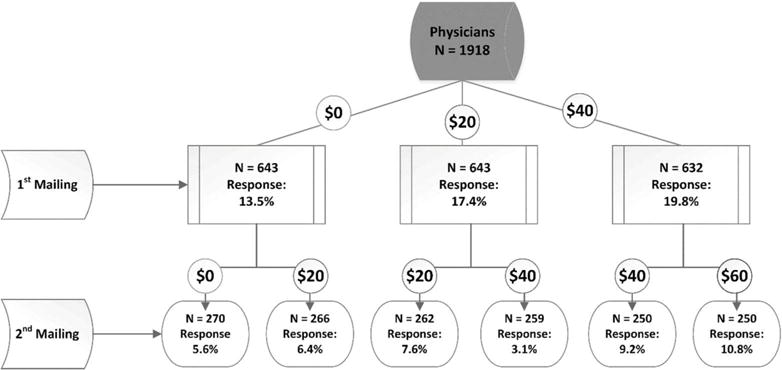

We sampled 1918 rheumatologists, and the response rate after the first email invitation for those randomized to no compensation was 13.5%, lower than for rheumatologists randomized to $20 (17.4%, p=0.05) or $40 (19.8%, p=0.003)(Appendix Figure). Across all groups, the response increased by 7.1% with a second invitation, yielding an overall response rate of 26% (n=495). After excluding surveys from non-practicing physicians(n=9) and those who left key questions blank (n=47), the effective sample size was 439, representing 255 (58%) metric physicians and 184 (42%) non-metric physicians. Overall, 44% responded that they “always practiced in a ‘treat-to-target’ manner’”, and non-metric physicians were no less likely to report this than metric physicians. Rheumatologists in a group rheumatology practice were most likely to be metric physicians, as were those who reported that they used TNFi therapy for >50% of their RA patients (Table 1). After multivariable adjustment, multi-physician rheumatology practice (OR=2.26,95%CI 1.09–4.69, referent to academic medical practice) and greater use of TNFi therapy (OR=1.69,95%CI 1.10–2.61) were the only factors significantly associated with being a metric physician, although there was a trend for older physicians to be less likely to be metric physicians (OR=0.78,95%CI 0.53–1.16 for age >60 vs. ≤60).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Rheumatologists Responding to Treat-To-Target Survey (n=439)

| Physicians Who Measure Quantitatively (n=255) |

Physicians Who Do Not Measure Quantitatively (n=184) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician Characteristics and Practice Patterns | |||

| Age, years | 56.7 (9.8) | 57.8 (9.9) | 0.20 |

| Male, % | 73 | 72 | 0.85 |

| Practice Setting | |||

| Academic | 24 | 23 | 0.005 |

| Solo practice | 18 | 28 | |

| Rheumatology group | 29 | 15 | |

| Multispecialty group | 22 | 20 | |

| Other | 11 | 10 | |

| >20 RA patients seen per week, % | 60 | 54 | 0.20 |

| Years in rheumatologic practice | |||

| ≤20 | 35 | 33 | 0.54 |

| 21–30 | 36 | 33 | |

| >30 | 30 | 35 | |

| Use TNF inhibitors for at least 50% of RA patients, % | 76 | 66 | 0.02 |

| How many TNF inhibitors must a patient fail before you choose another mechanism of action (MOA)?, % | |||

| Exactly 1 | 31 | 26 | 0.22 |

| 2 | 65 | 73 | |

| 3+ | 1 | 2 | |

| None; Non-TNF MOA biologics are my first line | 1 | 2 | |

| Beliefs about Treat-To-Target and RA Patient Outcomes | |||

| Doesn’t believe in “Treat to Target Hype”, % | 14 | 42 | <0.01 |

| What fraction of your RA patients achieve remission?, % | |||

| <20 | 20 | 17 | 0.90 |

| 20–<30 | 20 | 20 | |

| 30–<50 | 24 | 24 | |

| ≥50 | 37 | 39 | |

| What fraction of your RA patients achieve low disease activity?, % | |||

| <50% | 25 | 22 | 0.73 |

| 50%–<60% | 14 | 13 | |

| 60%–<80% | 32 | 35 | |

| ≥80% | 29 | 31 | |

Some column totals may not sum exactly to 100% due to rounding

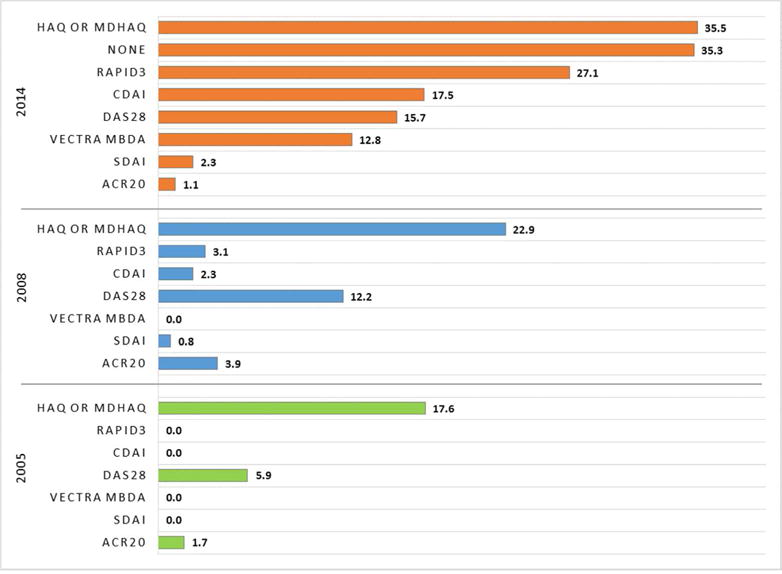

The quantitative tools used at most RA office visits were the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and variants (e.g. MDHAQ,mHAQ), and the RAPID3(6) (Figure 1). The CDAI(18%) and the DAS28(16%) and were less frequently used, as was the multi-biomarker disease activity (MBDA) test (13%). In total, 35% reported that they would not use any formal, quantitative measurement tool to assess and manage an RA patient with active disease. Amongst those physicians, history, physical exam, and clinical experience were typically cited as the methods used to assess and manage RA patients. Across the 2005, 2008, and 2014 surveys, use of quantitative metrics increased over time for all measures including HAQ (17.6%, 22.9%, and 35.5%), CDAI/SDAI (5.9%, 14.5%, and 33.2%), and RAPID3 (0%, 3.1%, 27.1%). Reasons reported by rheumatologists for measuring quantitatively or not (Table 2) included perceptions that measurement facilitated clinical care (76.1%) and specifically, medical decision-making(62.7%). Measurement tools were felt to be simple and useful (48.2%), and were helpful for satisfying quality reporting programs requirements (41.2%). Reasons reported for not measuring were: too time-consuming (62.5%) and not efficient electronically or using the electronic health record (34.8%). Less common was the sentiment that quantitative measurement was not needed to support care (29.3%). Results from the case scenarios (Appendix Table) showed that providing more quantitative information resulted in a 1.5 to 3.7-fold greater likelihood that the rheumatologist said that they would change or add DMARDs/biologics. Aggregating results across all three cases, metric physicians were 1.4 (95%CI 1.0–1.8, p<0.03)-fold more likely to change treatments versus non-metric physicians.

Figure 1.

Metrics Used by Rheumatologists for Patients with Active RA, as self-reported in 2014, 2008, and 2005 surveys*

*includes all physicians in survey sample

Table 2.

Reasons physicians do or do not routinely perform quantitative assessment

| What motivates you to measure RA metrics routinely? | N=255* |

|---|---|

| To facilitate/improve clinical care | 194 (76.1%) |

| To incorporate into medical decision making | 160 (62.7%) |

| Easy, simple & useful | 123 (48.2%) |

| For Medicare PQRS or other quality reporting programs | 105 (41.2%) |

| Participation in a research registry v | 47 (18.4%) |

| Insurance companies require it | 47 (18.4%) |

| Treat-to-Target trials (TICORA, BeST) show impressive data | 70 (27.5%) |

| Other | 21 (8.2%) |

| Why don’t you collect RA metrics routinely? | N=184* |

| Takes too much of my time | 115 (62.5%) |

| Not available on my EMR | 64 (34.8%) |

| Don’t need them | 54 (29.3%) |

| Too many to choose from | 32 (17.4%) |

| Not required by payors | 32 (17.4%) |

| Value is unproven | 31 (16.8%) |

| Requires labs (CRP or ESR) | 26 (14.1%) |

| Too difficult or complex | 23 (12.5%) |

| Language/communication difficulties (elderly, Spanish-speaking, etc.) | 20 (10.9%) |

responses not required nor mutually exclusive, so row totals do not sum to 100%. Metric physicians provided responses listed in the top half of the table regarding the reasons that they measure quantitatively; non-metric physicians provided the responses listed in the bottom half of the table regarding the reasons that they do not measure quantitatively.

Discussion

In this U.S. survey, 58% of rheumatologists self-reported using quantitative RA measurement tools at most visits. The HAQ and RAPID3 were most commonly used, followed by the CDAI, and use of all measures increased over the 10 year period covered by the 3 surveys. The reason most commonly given for valuing RA measurement was that the information collected was useful to facilitate clinical care. Conversely, the most commonly provided reason for not measuring was related to logistics; namely, physicians were not opposed to measuring, but they lacked the time and electronic tools to do so efficiently. Results from three simulated case scenarios showed that providing additional quantitative disease activity information led to more guideline-concordant treatment changes for RA patients with moderate disease activity, regardless of whether the rheumatologist was a metric physician or not.

Comparative information for the proportion of physicians in other settings measuring RA quantitatively is scant. An online survey sent to a sample of U.S. rheumatologists (14% response, n=125) found that the DAS28 (37%), RAPID3 (33%) and CDAI (21%) were used relatively frequently(7). Results from that study(7) and ours suggests that Canadians and rheumatologists internationally quantify RA disease activity more often than their U.S. counterparts(8)(9).

As noted, results from registries cannot easily serve to inform this question because quantifying disease activity and function is intrinsic to most physician-based registries (e.g. Corrona) (10). The ACR’s Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness registry extracts data routinely collected in rheumatologists’ electronic health record (EHR) systems (11). In 2016, 55% of RA patients had their disease activity measured quantitatively(12), similar to our results and that from an Australian report(13). However, these results are constrained by important generalizability concerns; rheumatologists participating in RISE are early adopters and may be more likely to measure disease activity to satisfy quality reporting metrics tied to financial incentives.

Logistical issues were the main barriers to physicians not measuring quantitatively, and methods and tools to efficiently collect data from patients (with or without additional physician information) are needed. Several examples of electronic tools to satisfy this need have been described (14–16). While a feature-rich electronic system provided by an EHR vendor would be an attractive solution, few if any presently exist. A standalone disease activity measurement system that can be integrated with the EHR using informatics standards that foster interoperability (e.g. HL7, FHIR) may be particularly attractive for many settings(14).

Providing rheumatologists an incentive of $20–$40 yielded an approximately 5–10% higher survey response rate. A second contact one month later boosted response by approximately 7%, although further increasing the incentive by $20 had minimal effect. Although lower than desired, our response rate of 26% is typical for an online physician survey (17). Prior surveys conducted by the authors and others published in the medical literature generally find that response rates to a physician survey range from 13% (18) to 35% (19). The survey topic, credibility of the authors, and follow-up reminders increase response (19), as do incentives(20).

Notable features of our study include the conduct of three serial surveys over time of a large number of U.S. rheumatologists with similar demographics and practice settings to the ACR’s membership (J. Martin, ACR Membership Specialist, personal communication 2017). However, we recognize that due to the relatively low (albeit typical) response rate, our results may not be generalizable to other rheumatologists. It is also possible that survey respondents may have had greater interest in the topic and be more likely to measure quantitatively. If so, then our findings represent a ‘best case scenario’ with respect to the proportion of U.S. rheumatologists measuring quantitatively.

In conclusion, these results show that for many rheumatologists, quantitative measurement in RA is not an essential facet of routine care. Encouragingly, U.S. rheumatologists seem generally agreeable to obtain quantitative data from their patients if only it was made more efficient to collect, ideally through electronic means. Developing and deploying embedded EHR-based tools, or standalone systems integrated with EHRs, would serve this goal and facilitate evidence-based RA management and lead towards more optimal quality of care. As part of a future research agenda, it may be fruitful to explore the identification and outcomes in RA patients in whom qualitative physician judgment deems them to be “doing well” but in whom this assessment is discordant with clinical remission or low disease activity using quantitative measures.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIAMS P60 AR064172

Appendix Figure. Rheumatologists’ Response to Internet Survey per Financial Incentive Offered.

n’s refer to the number of surveys sent in each randomized wave.

Explanation: 1,918 physicians had valid email addresses and were eligible to participate; 39 (2.0%) opted out of the current and future surveys. Among those randomized to receive no compensation (N=643), the response rate was 13.5% after a single email contact, which was lower than those who were randomized to receive either $20 or $40, wherein the response rates were 17.4% (p=0.05 compared to no compensation) and 19.8% (p=0.003 compared to no compensation), respectively. The pooled response rate of 18.6% with either incentive ($20 or $40) was also significantly greater (p=0.005) compared to no compensation, but the response rate to the $20 and $40 incentive amounts were not significantly different from each other (p=0.28).

The incremental response to a second email solicitation was 7.1% (95% CI 5.8–8.3%), pooled across all arms. Response to the second email contact was not greater for the groups randomized to receive an additional $20. Rheumatologists offered $60 (randomized to $40 initially, then randomized to an additional $20) had the numerically highest incremental response rate, with an additional 10.8% responding to the second email contact, yielding an overall response rate for this group of 30.6%.

Appendix Table.

Case Scenario Results for Whether Data from Quantitative Assessment Impacted Likelihood to Change or Add a DMARD or Biologic

| Amount of Clinical and Metric Information Provided | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of info/Metrics | Limited | Expanded | Complete |

| Case Detail* | Swollen knee & wrist | MTX, Pred, NSAID, AM stiffness 10″, | MTX/ETN, AM stiffness <15″; Pain in MCPs, Wrist |

| Quantitative disease activity | none | Patient pain 2/10, TJC 5, SJC 1 | TJC5, SJC 1 |

| Laboratory data | none | ESR 32, CRP 1.1 mg/dl | CRP 1.5 mg/dl |

| Composite Metrics Provided | none | HAQ 0.5 | DAS 4.10, CDA 12, SDAI 13 GAS 15 |

|

Treatment Changes*,** No DMARD or Biologic Change, % |

51 | 22 | 16 |

| Non-biologic DMARD Change, % | 31 | 49 | 47 |

| Biologic Add/Switch, % | 19 | 30 | 37 |

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) for Any DMARD/Biologic Change | Referent | 3.7 (2.8–5.0) | 5.5 (4.1–7.5) |

| Referent | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | ||

case and other treatment options (e.g. joint injection) were abbreviated or truncated for brevity

may not sum exactly to 100% due to rounding

Explanation: The referent case scenario (left-most column) provided limited clinical information (a swollen wrist and knee) and no RA disease metrics was likely to be managed with joint injection (41%) [not shown]; 49% of rheumatologists said they would change DMARD or biologics. The second case (middle column) provided additional clinical, laboratory (ESR, CRP) and metrics (HAQ, pain VAS, patient global); rheumatologists were 3.7 (2.8–5.0) times more likely to change or add DMARDs or biologics (78%). With yet more quantitative information, (right-most column), rheumatologists were 1.5 (1.1 – 2.0) fold more likely to change DMARDs/biologics (84%) compared to the expanded case (middle column), and 5.5 times likely to change therapy compared to case with the least information.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none (all coauthors)

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, Bykerk V, Dougados M, Emery P, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:3–15. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1–26. doi: 10.1002/art.39480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715. Published Online: 06 March 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, Robbins ML, Neogi T, Michaud K, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:640–7. doi: 10.1002/acr.21649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cush JJ. Biological drug use: US perspectives on indications and monitoring. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 4):iv18–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.042549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pincus T, Swearingen CJ, Bergman M, Yazici Y. RAPID3 (Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3), a rheumatoid arthritis index without formal joint counts for routine care: proposed severity categories compared to disease activity score and clinical disease activity index categories. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2136–47. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glauser TA, Ruderman EM, Kummerle D, Kelly S. Current Practice Patterns and Educational Needs of Rheumatologists Who Manage Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2014;1:31–44. doi: 10.1007/s40744-014-0004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haraoui B, Bensen W, Thorne C, Wade J, Deamude M, Prince J, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: a Canadian patient survey. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014;20:61–7. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haraoui B, Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Breedveld FC, Burmester G, Codreanu C, et al. Treating Rheumatoid Arthritis to Target: multinational recommendations assessment questionnaire. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1999–2002. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.154179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kremer JM. The CORRONA database. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yazdany J, Robbins M, Schmajuk G, Desai S, Lacaille D, Neogi T, et al. Development of the American College of Rheumatology’s Rheumatoid Arthritis Electronic Clinical Quality Measures. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1579–90. doi: 10.1002/acr.22984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yazdany J, Bansback N, Clowse M, Collier D, Law K, Liao KP, et al. Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness: A National Informatics-Enabled Registry for Quality Improvement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1866–73. doi: 10.1002/acr.23089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor A, Bagga H. Measures of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in Australian clinical practice. ISRN Rheumatol. 2011:ID437281. doi: 10.5402/2011/437281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yen PY, Lara B, Lopetegui M, Bharat A, Ardoin S, Johnson B, et al. Usability and Workflow Evaluation of “RhEumAtic Disease activitY” (READY). A Mobile Application for Rheumatology Patients and Providers. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7:1007–24. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2016-03-RA-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman ED, Lerch V, Billet J, Berger A, Kirchner HL. Improving the quality of care of patients with rheumatic disease using patient-centric electronic redesign software. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:546–53. doi: 10.1002/acr.22479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman ED, Lerch V, Jones JB, Stewart W. Touchscreen questionnaire patient data collection in rheumatology practice: development of a highly successful system using process redesign. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:589–96. doi: 10.1002/acr.21560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dykema J, Jones NR, Piche T, Stevenson J. Surveying clinicians by web: current issues in design and administration. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36:352–81. doi: 10.1177/0163278713496630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott A, Jeon SH, Joyce CM, Humphreys JS, Kalb G, Witt J, et al. A randomised trial and economic evaluation of the effect of response mode on response rate, response bias, and item non-response in a survey of doctors. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:32. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinisch JF, Yu DC, Li WY. Getting a Valid Survey Response From 662 Plastic Surgeons in the 21st Century. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:3–5. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]