Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The best established cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are levels of amyloid-β 42 (Aβ42), total tau (tau) and phosphorylated tau-181 (ptau). We examined whether a widely used commercial immunoassay for CSF Aβ42, tau and ptau provided stable measurements over ~10 years.

METHODS

INNOTEST assay values for CSF Aβ42, tau and ptau from Washington University in St. Louis and VU Medical Center, Amsterdam, were evaluated.

RESULTS

Aβ42 values as measured by the INNOTEST assay drifted upward by approximately 3% per year over the last decade. Tau values remained relatively stable, while results for ptau were mixed.

DISCUSSION

Assay drift may reduce statistical power or even confound analyses. The drift in INNOTEST Aβ42 values may reduce diagnostic accuracy for AD in the clinic. We recommend methods to account for assay drift in existing datasets and to reduce assay drift in future studies.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, assay drift, biomarker, cerebrospinal fluid, cut-off, INNOTEST, quality control, amyloid

1. Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD), a fatal neurodegenerative disease, is the most common cause of dementia in older adults and affects an estimated 5.4 million individuals in the United States alone [1]. Clinicopathologic studies demonstrate that AD pathology—amyloid plaques comprised of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) and neurofibrillary tangles comprised of tau—starts accumulating in the brain many years prior to the onset of dementia, during the preclinical phase of AD [2–7]. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers have shown great promise in identifying individuals with both preclinical AD and symptomatic AD (i.e., mild cognitive impairment [MCI] due to AD or AD dementia) [8–10]. The best established CSF biomarkers for AD are the concentrations of amyloid-β 42 (Aβ42), total tau, and phosphorylated tau181 (ptau) [11]. Low levels of CSF Aβ42 consistent with brain amyloid deposition are evident ~10–20 years before the onset of dementia due to AD [9, 10]. Individuals with symptomatic AD have low levels of CSF Aβ42 and elevated levels of CSF tau and ptau, which are thought to reflect tau-related neuronal injury downstream of amyloid deposition [12, 13].

Levels of CSF Aβ42, tau, and ptau are currently used in the clinic to evaluate for AD brain pathology when patients have an unclear cause of their cognitive problems, as often occurs in early-onset dementia and atypical dementia syndromes [14]. CSF biomarkers and brain molecular imaging are now being utilized as enrollment criteria for clinical prevention trials in cognitively normal individuals as well as for treatment trials in patients with MCI or very mild dementia [15–19]. Biomarkers are also being used as endpoints in clinical trials to demonstrate that drugs are effectively engaging their therapeutic targets [18]. Once effective therapies for AD are developed, it is likely that testing for preclinical AD will become routine and guide medical decision making.

Given the importance of CSF biomarkers in AD research, clinical practice, and clinical trials, it is critical that biomarker assays provide valid and stable results over time. A variety of pre-analytical and analytical factors are known to affect assay results [20]. One limitation of commercial immunoassays is a typical shelf life of approximately one year, so biorepositories that collect samples over many years typically generate data from many different assay lots. The absence of certified reference materials and reference methods contributes to assay variability and makes lot bridging difficult [21]. In the current study we examined the stability of Aβ42, tau and ptau measurements as assessed by the widely used INNOTEST assay over approximately one decade on CSF samples collected, stored and analyzed at the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL). We then confirmed our major results using independent data from the Neurochemistry Laboratory at VU Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands (VUMC). We found evidence of upward drift in INNOTEST Aβ42 measurements that could have significant implications for the use of CSF biomarkers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Participants, standard protocol approvals and consents

The majority of the study utilized CSF biomarker and amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging data obtained from participants enrolled in research studies of normal aging and dementia at the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center at WUSTL from December of 2003 to February of 2015. The Washington University Human Research Protection Office approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

An independent set of analyses utilized INNOTEST data on two pooled CSF samples used for quality control (QC) purposes in the Neurochemistry Laboratory at VUMC in the Netherlands. The two pools were formed from left-over diagnostic samples in agreement with the Dutch Code of Conduct of use of Human Material. The first pool had biomarker levels that were typical for AD (low Aβ42 and high ptau), and the second had a typical control profile with high Aβ42 and low ptau.

2.2 CSF collection, processing and analysis

CSF obtained from participants at WUSTL was collected under standardized operating procedures that have not changed over time. CSF was collected, gently inverted to disrupt potential gradient effects, centrifuged at low speed to pellet any cellular debris, aliquoted into polypropylene tubes and stored at −80°C as previously described [22]. All assays used freshly thawed aliquots of CSF that had only been frozen once and had been stored continuously at −80°C after sample processing the day of collection. Aβ42, total tau, and ptau were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using INNOTEST assays (Fujirebio [formerly Innogenetics], Ghent, Belgium) at two different times: 1) batched-analyzed as samples were obtained (referred to as the “multi-run” dataset) and 2) all samples assayed together in 2013 using a single assay lot (“single-run” dataset).

At VUMC, CSF samples were centrifuged at 1800–2100 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C within 2 hours of collection. Left-over samples used for diagnostic purposes were pooled based on their CSF biomarker profile determined by INNOTEST ELISA and aliquots were stored at −80°C for use as QC samples during routine biomarker analyses.

2.3 Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging

Participants at WUSTL underwent amyloid PET imaging with Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) within one year of CSF collection as previously described [23]. The mean cortical standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) was calculated from FreeSurfer regions within the prefrontal cortex, precuneus, and temporal cortex, with partial volume correction [24, 25]. PiB-positivity was defined as an SUVR>1.42, commensurate with a mean cortical binding potential of 0.18 defined previously for PiB positivity [24].

2.4 Statistical analyses

Multi- and single-run INNOTEST values were compared using Spearman correlations. Bland-Altman plots demonstrated the difference in multi- and single-run assay values over the assay concentration range. Linear regression analyses tested for significant changes in values over time. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed to identify the Aβ42 cut-off value with the highest sensitivity and specificity for amyloid PET positivity. These analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 6.07 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Passing-Bablock comparisons between the multi- and single-run INNOTEST values were performed with MedCalc Statistical Software version 17 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). The within-subject longitudinal change in analyte concentrations was evaluated using general linear mixed models, with random intercepts and slopes at the subject level, which is a mixed hierarchical model for longitudinal/repeated measurements [26]. The model assumes a subject-specific linear growth or decline pattern over time, in addition to the within-subject random errors measuring deviations from the linear pattern. The models were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood estimation, with the approximate F test denominator degrees-of-freedom based on the Satterthwaite method [27]. Linear mixed model analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of multi-run and single-run INNOTEST values

CSF samples from 163 individuals were evaluated (see Table 1 for participant characteristics). For the comparison of multi- and single-run data, one CSF sample was chosen with a random number generator to represent each of the 163 individuals. We compared values for Aβ42, tau and ptau measured in CSF samples that were initially assayed with multiple lots of INNOTEST assays between 2003 and 2015 (multi-run dataset) with values obtained with a single lot of assays in 2013 (single-run dataset) [26]. The CSF samples were initially assayed for Aβ42, tau and ptau 7.2 ± 15.6 months following LP using INNOTEST lots that were available and within their expiration date. Some of the initial measurements failed strict quality control guidelines so the samples were re-run with later assays, which contributed to the wide range of time intervals for LP to initial assay. The multi-run dataset included more than 38 different runs of INNOTEST assays for Aβ42. Before 2011, the lot number was not always recorded, so the total number of lots used is not known. The mean time between the multi-run INNOTEST assay and single-run INNOTEST assay was 5.8 ± 2.2 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who contributed CSF samples used for the single-run and multi-run INNOTEST comparisons

| n= | 163 |

|---|---|

| CDR 0/0.5/1/2/3 (n)# | 159/4/0/0/0 |

| Age at LP (years)† | 62.6 ± 8.5 |

| Gender (% female) | 67% |

| LP until initial assay (months)† | 7.2 ± 15.6 |

| Inter-assay interval (years)†+ | 5.8 ± 2.2 |

| APOE ε4 frequency | 0.20 |

| Multi-run Aβ42 (pg/ml)† | 686 ± 265 |

| Single-run Aβ42 (pg/ml)† | 1168 ± 362 |

| Multi-run Tau (pg/ml)† | 269 ± 178 |

| Single-run Tau (pg/ml)† | 298 ± 177 |

| Multi-run pTau (pg/ml)† | 53 ± 28 |

| Single-run pTau (pg/ml)† | 55 ± 29 |

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): cognitively normal 0, very mild dementia 0.5, mild dementia 1, moderate dementia 2, severe dementia 3;

mean ± standard deviation;

time interval between single-run and multi-run assays

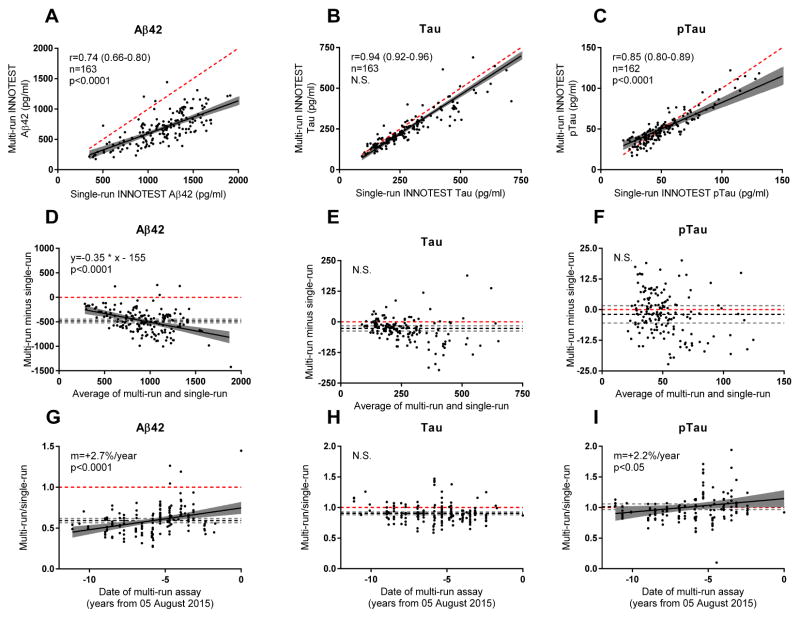

The multi- and single-run values for both tau and ptau were strongly positively correlated (tau, Spearman r=0.94, p<0.0001; ptau, r=0.85, p<0.001), but less so for Aβ42 (r=0.74 p<0.0001) (Figs. 1A–C). The slopes for the multi-run INNOTEST versus single-run INNOTEST values, which should ideally be 1, were significantly lower than 1 for both Aβ42 and ptau (p<0.0001), indicating that the single-run values were higher. To further evaluate whether the multi- and single-run INNOTEST values were in agreement, we compared the two measurements using Bland-Altman plots (Figs. 1D–F). For Aβ42 measurements, the multi-run values were an average of 482 pg/ml lower than single-run values (95% CI, −444 to −519 pg/ml) (Fig. 1D). This difference was more pronounced in samples with high Aβ42 (p<0.0001). For tau, multi-run values were an average of 27 pg/ml lower (95% CI −38 to −16 pg/ml), but this difference did not vary by tau concentration (Fig. 1E). There was no significant difference in ptau levels by Bland-Altman analysis (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1. Comparison of multi-run and single-run INNOTEST values.

Multi-run values were positively correlated with single-run INNOTEST values for (A) Aβ42, (B) tau and (C) ptau. Bland-Altman plots were used to compare multi-run and single-run values for (D) Aβ42, (E) tau and (F) ptau. Multi-run values, as compared to single-run values, increased over time for (G) Aβ42 and (I) ptau but not (H) tau. Each point represents one CSF sample from one individual. The black solid line represents the best fit regression line. The grey region surrounding the regression line represents the 95% confidence intervals for the regression line. The dashed red line represents identity, which would occur if the multi-run value equaled the single-run value. For D–I, the black dashed line represents the mean of all the values and the dashed grey lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of the mean. The Spearman correlation coefficient (r), number of individuals (n), and slope (m) is represented. The p value indicates whether the slope of the regression line is significantly different from the slope of the identity line (the slope of the identity line is 1 for A–C and 0 for D–I). August 5, 2015 refers to the last assay date in the multi-run dataset.

Passing-Bablock regression analyses were also performed. For Aβ42, there were large and significant systematic and proportional differences (parameter a=189, 95% CI 83 to 315, parameter b=1.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.6), which were consistent with the Bland-Altman analyses. For tau, there were small but significant proportional differences (parameter b=1.16, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.23) but not systematic differences (parameter a=−9, 95% CI −21 to 6), which were consistent with the Bland-Altman analyses. For ptau, there were small but significant systematic (parameter a=−4.3, 95% CI −8.7 to −0.8) and proportional differences (1.14, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.23), which were not apparent in Bland-Altman analyses. Passing-Bablock analyses are non-parametric, which may explain why these analyses were somewhat different than Bland-Altman analyses.

To evaluate potential lot-specific effects, we plotted the ratio of multi- to single-run values for each of the three analytes as a function of the date of the initial (multi-run) assay from 2003 to 2015. This ratio would be 1 if the values were the same. As expected from Bland-Altman analyses, multi-run values for both Aβ42 and tau were lower than single-run values, resulting in a ratio <1 for most samples (Figs. 1G, 1H). Importantly, the Aβ42 values increased as a function of assay date, with values drifting upward over time at 2.7% per year (p<0.0001) (Fig. 1G). Tau values did not vary as a function of assay date (Fig. 1H), whereas ptau values drifted upward at 2.2% per year (p<0.05, Fig. 1I).

The potential scientific impact of the upward drift in Aβ42 values, especially in study of within-individual change, is illustrated in Fig. 2. For these analyses, we used the same cohort that was represented by a single CSF sample in the multi-run versus single-run analyses (Fig. 1, Table 1). 139 of the 163 individuals underwent multiple LPs and contributed a total of 317 samples to our biorepository that were analyzed for Fig. 2. Aβ42 values for individuals who had undergone more than one CSF collection were plotted as a function of age at time of LP. When the multi-run values were analyzed, Aβ42 values did not change significantly within individuals as they aged (the decrease of 0.34 pg/ml/year was not significantly different from no change, p>0.05, Fig. 2A). However, analysis of the single-run values revealed a highly significant decline in Aβ42 levels within individuals as they aged (decrease of 16.05 pg/ml/year, p<0.0001, Fig. 2B), reflecting amyloid deposition in some of these middle- and older-aged individuals. For tau, the rate of intra-individual change was comparable: an increase of 4.18 pg/ml/year (p<0.0001) for the multi-run dataset and 4.46 pg/ml/year (p<0.0001) for the single-run dataset. There was no significant change with age in ptau levels in the multi-run dataset (2.99 pg/ml/year, p>0.05), but there was a small but significant increase with age in ptau levels in the single-run dataset (0.84 pg/ml/year, p<0.0001). These analyses demonstrate that assay drift, assay lot-to-lot variability, and potentially plate-to-plate technical variability, can completely mask robust biological effects.

Fig. 2. Intra-individual change in CSF Aβ 42 as a function of age.

Multi-run (A) and single-run INNOTEST Aβ42 values (B) are plotted as a function of age at time of CSF collection. Each point represents one CSF sample, and samples from a single individual are connected with a line. The overall group change in Aβ42 as a function of age (m) was calculated using linear mixed models and is represented by a dashed red line.

3.2. Examination of lot-to-lot variability using a dataset from VUMC Amsterdam

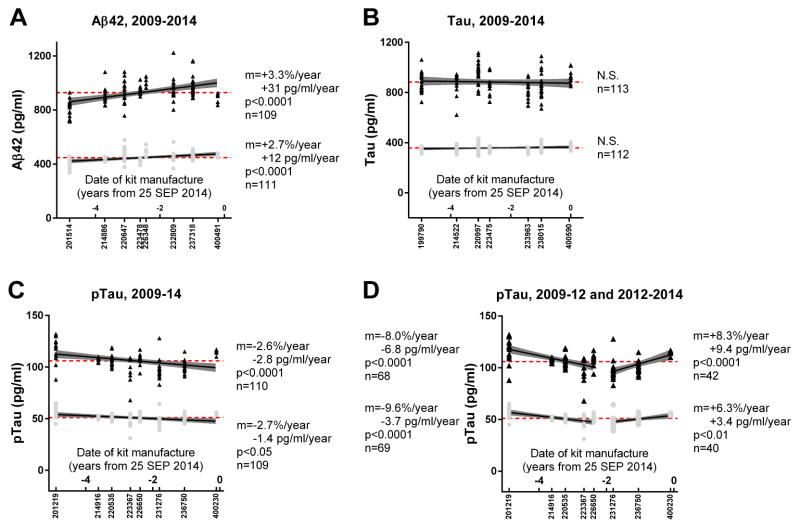

To examine whether drift in INNOTEST Aβ42 measurements was an issue only at Washington University, or present in other datasets and therefore suggestive of an issue with the INNOTEST assay, we obtained an independent dataset from VUMC. Aliquots of two pooled quality control (QC) samples had been included on all INNOTEST assay plates from 2009 to 2014 as part of VUMC’s internal QC program. The date of kit manufacture was obtained from Fujirebio (the maker of INNOTEST) for each assay lot and was used as the proxy for “time” in evaluating for potential assay drift. Notably, there was a significant amount of variability in the measurements of the same sample, even when performed with the same lot of assays, which is consistent with prior reports [27].

Strikingly similar to what was observed in the WUSTL cohort, analyses revealed an upward drift in Aβ42 values by ~3% per year over 5 years (Fig. 3A). Tau values for the pooled VUMC samples remained stable (Fig. 3B), whereas ptau levels showed a decline of ~3% per year (Fig. 3C), opposite of what was estimated in the WUSTL samples (i.e., increase of ~2% per year, Fig. 1I). We examined whether the drift in assay values over five years was better described by a single regression line or two regression lines. Aβ42, tau and pau measurements were subdivided into segments representing three or more assay lots to evaluate for sustained assay drift. Segments with only two assay lots would have simply represented lot-to-lot variability. We found that only ptau had two segments with slopes that were significantly different from one another. Ptau levels initially decreased over the first five assay lots (manufactured in November 2009 until May 2012), then increased over the last three assay lots (manufactured December 2012-August 2014, Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Values for two samples measured with multiple INNOTEST assay lots manufactured over 5 years.

Values for (A) Aβ42, (B) tau and (C–D) ptau for aliquots of two pooled CSF samples from VUMC. Black points represent values for one sample; grey points represent values for a second sample. The lot number is listed below the X-axis, and the distance along the X-axis corresponds to the relative date of kit manufacture. The dashed red line represents the average value for the sample including all measurements. The change in assay values over time (m), whether the values change significantly over time (p) and the total number of measurements for each sample (n) are represented. For D, the information corresponding to the first five assay lots is listed on the left and the information corresponding to the last three assay lots is listed on the right.

3.3. Aβ42 cut-off values that correspond to a positive amyloid PET scan

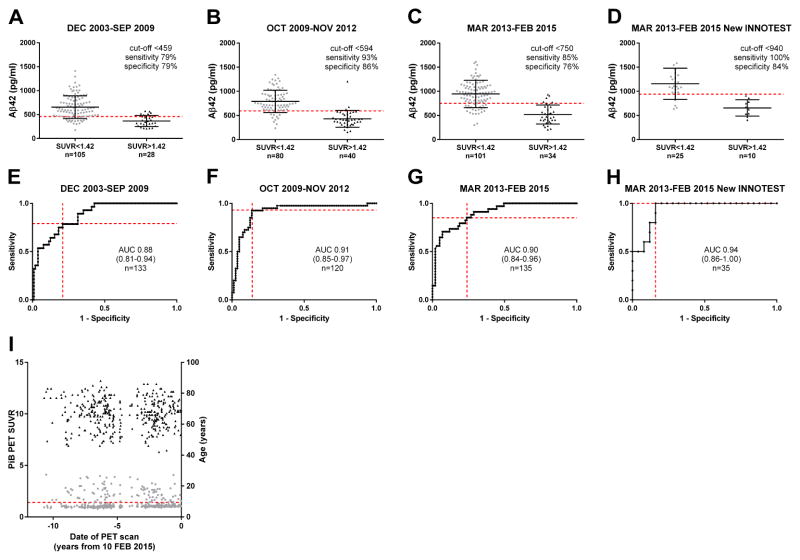

To further evaluate whether INNOTEST Aβ42 values were changing over time due to assay drift, we compared multi-run INNOTEST Aβ42 values to amyloid PiB PET results. We reasoned that if INNOTEST Aβ42 values were stable, the CSF Aβ42 value that corresponds to a positive amyloid PET scan should not change over time. The WUSTL cohort used for our earlier analyses (Table 1, Figs. 1–2) did not have sufficient PiB PET data, so we used a different cohort that is described in Table 2. Each individual was represented by a single PiB PET scan that occurred within one year of CSF collection. Aβ42 levels were measured by INNOTEST an average of 4.7 ± 4.7 months following LP. The time interval between LP and PiB PET was an average of 1.1 ± 3.6 months. The cohort was divided into three relatively equal-sized groups representing three assay periods. A subset of the March 2013-February 2015 group, which was assayed with the “New INNOTEST” with lot numbers beginning with the number “4,” was also analyzed separately. The New INNOTEST assay utilized ready-to-use standards as compared to the previous assays which required dilution of a single standard to create the standard curve.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants studied in the INNOTEST comparison to amyloid PiB PET binding

| Multi-run INNOTEST assay run date | All | DEC 2003-SEP 2009 | OCT 2009–NOV 2012 | MAR 2013-Feb 2015 | MAR 2013-FEB 2015 New INNOTEST subset | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid PiB PET status‡ | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | |

| n= | 388 | 105 | 28 | 80 | 40 | 101 | 34 | 25 | 10 |

| CDR 0/0.5/1/2/3 (n)# | 361/25/1/1/0 | 98/7/0/0/0 | 18/9/0/1/0 | 78/2/0/0/0 | 35/5/0/0/0 | 100/0/1/0/0 | 32/2/0/0/0 | 25/0/0/0/0 | 10/0/0/0/0 |

| Age at LP (years)† | 67.1 ± 9.4 | 69.9 ± 8.2 | 72.1 ± 7.2 ** | 62.0 ± 8.7 | 71.9 ± 7.8 **** | 65.6 ± 8.3 | 73.1 ± 6.3 **** | 66.1 ± 6.2 | 72.7 ± 4.8 ** |

| Gender (% female) | 59% | 72% | 50% * | 63% | 45% | 53% | 44% | 56% | 60% |

| APOE ε4 frequency | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.41 **** | 0.14 | 0.34 *** | 0.14 | 0.37 ** | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| Multi-run Aβ42 (pg/ml)† | 702 ± 301 | 654 ± 237 | 365 ± 115 **** | 790 ± 232 | 431 ± 174 **** | 945 ± 283 | 519 ± 196 **** | 1156 ± 323 | 654 ± 169 **** |

| Multi-run Tau (pg/ml)† | 308 ± 216 | 245 ± 110 | 466 ± 192 **** | 214 ± 91 | 515 ± 417 **** | 272 ± 126 | 465 ± 260 **** | 271 ± 91 | 498 ± 306 * |

| Multi-run pTau (pg/ml)† | 58 ± 30 | 48 ± 18 | 74 ± 24 **** | 50 ± 29 | 84 ± 39 **** | 51 ± 22 | 81 ± 36 **** | 52 ± 18 | 98 ± 43 *** |

A mean cortical standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) > 1.42 was considered positive;

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): cognitively normal 0, very mild dementia 0.5, mild dementia 1, moderate dementia 2, severe dementia 3;

mean ± standard deviation; Comparisons are between amyloid PiB PET negative and positive groups. Student’s T-tests were performed on continuous data and Chi square tests were performed on categorical data.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001,

p<0.0001

ROC analyses were performed and cut-off values for Aβ42 that provided the best sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between amyloid PET-positive (PiB SUVR > 1.42) and amyloid PET-negative (PiB SUVR ≤ 1.42) status were determined. The Aβ42 cut-off that corresponded best to a positive PiB PET scan varied markedly among the different assay periods: <459 pg/ml for December 2003-September 2009, <594 pg/ml for October 2009-November 2012, <750 pg/ml for March 2013-February 2015 and <940 pg/ml for the March 2013-February 2015 subset of samples assayed with the New INNOTEST (Fig. 4). Importantly, CSF Aβ42 was a good predictor of PiB status in all groups: the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was high and comparable among all the groups (0.88–0.94). We considered the possibility that PiB PET values could be changing over time, so we examined PiB PET values as a function of the date of the scan. We found that PiB PET values did not change over time (Fig. 4I). Since older individuals are more likely to be PiB positive, we also examined whether the age of individuals in our cohort changed over time. We found that the average age did not change significantly across the PET scan period (Fig. 4I).

Fig. 4. Aβ 42 cut-off value corresponding to a positive PiB PET scan for different assay periods.

The WUSTL cohort was split into similarly sized groups representing three different assay periods: (A, E) December 2003-September 2009, (B, F) October 2009-November 2012 and (C/G) March 2013-February 2015. A subset of the group in (C, G) that was measured with the New INNOTEST assay was also analyzed (D, H). ROC analyses comparing Aβ42 levels with cortical PiB PET positivity were performed for the different groups, and the ROC curves are shown in E–H with the area under the curve (AUC) and the number of individuals (n) represented. Aβ42 cut-offs that corresponded to PiB PET positivity (SUVR>1.42) were determined. The sensitivity and specificity of the cut-offs are shown by red dashed lines in E–H. The cut-offs were applied to the groups in A–D and are represented by dashed red lines. I demonstrates the stability of PiB PET standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) over time. Black points are age (right Y-axis) at the time of scan, and grey points are PiB PET SUVR (left Y-axis). The dashed red line represents the cut-off for a positive SUVR (>1.42).

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that CSF Aβ42 values, as measured by the INNOTEST assay in two independent datasets (WUSTL and VUMC), drifted upward by approximately 3% per year over the last decade. In contrast, INNOTEST tau measurements were relatively stable. Changes in INNOTEST ptau measurements were more complex: ptau slightly drifted upward in the WUSTL sample from 2003–2015, but drifted downward in the VUMC sample from 2009–2012 and upward from 2012–2014. We cannot rule out that storing CSF samples at −80°C for more than 10 years affected analyte levels and contributed to assay drift. However, we compared Aβ42 levels measured shortly after CSF collection to amyloid PiB PET and obtained a consistent result: Aβ42 levels corresponding to a positive PiB PET scan increased markedly over time, from <459 pg/ml in 2003–2009 to <940 pg/ml in the latest assays.

While an upward drift in Aβ42 of ~3% per year may seem small, recent values are approximately 30% higher than values obtained one decade ago, which could have a major effect on whether a given value is above or below a cut-off value. For example, if the cut-off of <459 pg/ml Aβ42 (obtained with the December 2003-September 2009 data) is applied to the most recent New INNOTEST data, 9 of 10 PiB positive individuals would be incorrectly classified as normal based on their CSF Aβ42 values. It is unclear whether drift in CSF Aβ42 values is a problem in clinical testing for AD dementia, as the quality control process for diagnostic laboratories using the INNOTEST kit is rigorous. However, INNOTEST Aβ42 assays are used in some clinical settings to establish the presence of β-amyloid pathology, and if Aβ42 assay drift is present and cut-off values are not adjusted, patients could falsely test negative for amyloid pathology.

Our findings have important implications for centers that use INNOTEST Aβ42 data from many assay lots and/or collected over many years. Methods to minimize the impact of assay drift include the following: 1) Assay lot/date can be included as a co-variate; 2) Studies can select data from samples that have been assayed by a single assay lot; 3) Different cut-off values (e.g. for amyloid positivity) for different assay lots/dates can be defined; 4) Samples can be re-run using a single lot of assays (recommended for evaluation of longitudinal CSF biomarker changes); and 5) Existing datasets that include common samples that are run on every assay plate can undergo post-hoc lot bridging if measurement variability within a lot is small. Using these methods to account for assay drift can improve the statistical power and ultimate validity of biomarker analyses.

To reduce assay drift in the future, we recommend limiting the number of lots used, performing a priori formal lot bridging, and including biological QC samples on every plate. New, high-throughput automated platforms (e.g., Roche Elecsys and Fujirebio Lumipulse) may decrease measurement variability [28], but it will still be important to continually evaluate the stability of measurements obtained with different lots of reagents over time. The Alzheimer’s Association Global Consortium for Biomarker Standardization has been developing international reference materials and methods for CSF AD biomarkers [21]. Such efforts are expected to play a critical role in improving the reliability of biomarker measurements in the future [20, 27]. Furthermore, development of much needed certified reference materials could substantially reduce variability introduced by the use of different lots of standards both within a given assay and between assays.

HIGHLIGHTS.

INNOTEST Aβ42 values have drifted upward by ~3% per year over the past decade

INNOTEST tau values have remained fairly stable over the past decade

Upward drift in INNOTEST Aβ42 values could lead to under-diagnosis of AD

There are strategies to control for assay drift in research datasets

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers for Alzheimer disease (AD) are increasingly being used in clinical diagnosis, clinical trials and research. The stability of widely used CSF biomarker assays over many years has not previously been published.

Interpretation: We found that Aβ42 values as measured by the widely used INNOTEST immunoassay have been drifting upward over the past decade. We suggest research design strategies to control for assay drift that may improve the power and validity of existing CSF biomarker datasets.

Future directions: Our findings emphasize the need for rigorous quality controls procedures for biomarker assays including certified reference materials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Brian Gordon for facilitating our analysis of PiB PET data. We would like to express our gratitude to the research volunteers who participated in the studies from which these data were obtained. This study was supported by National Institute on Aging grants P01AG026276 and P01AG03991 (JC Morris, PI).

Abbreviations

- Aβ42

amyloid β42

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- AUC

area under the curve

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PiB

Pittsburgh Compound B

- ptau

phosphorylated tau-181

- QC

quality control

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SUVR

standardized uptake value ratio

- tau

total tau

- VUMC

Vrijie University Medical Center

- WUSTL

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Schindler is supported by UL1 TR00448, Sub-Award KL2 TR000450 and R03AG050921. Dr. Schindler has a family member with stock in Eli Lilly. Dr. Teunissen serves on the advisory board of Fujirebio and Roche and performed contract research for IBL, Shire, Boehringer, Roche and Probiodrug. Dr. Teunissen received grants from the European Commission, the Dutch Research Council (ZonMW), Association of Frontotemporal Dementia/Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, ISAO and the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. Dr. Teunissen received lecture fees from Roche and Axon Neurosciences. Dr. Morris has served as a consultant for Lilly USA and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Morris receives research support from Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and is funded by NIH grants P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276 and UF01AG032438. Dr. Holtzman is supported by NIH grants including P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276. Dr. Holtzman is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics. He is a consultant over the last year for Genentech, AbbVie, Neurophage, Denali and Eli Lilly. Dr. Scheltens has acquired grant support for his institution from GE Healthcare, Danone Research, Piramal and MERCK. In the past two years Dr. Scheltens has received consultancy/speaker fees (paid to his institution) from Lilly, GE Healthcare, Novartis, Sanofi, Nutricia, Probiodrug, Biogen, Roche and EIP Pharma. Dr. Xiong is supported by NIH grants including P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276, R01AG034119 and R01AG053550 (Dr. Xiong). Dr. Fagan is supported by NIH grants including P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276 and UF01AG03243807. Dr. Fagan is on the Scientific Advisory Boards for Roche Diagnostics, IBL International and AbbVie and consults for Biogen, DiamiR, LabCorp and Araclon Biotech/Griffols.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778–83. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price J, Ko A, Wade M, Tsou S, McKeel D, Morris J. Neuron number in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1395–402. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez-Isla T, Price J, McKeel D, Morris J, Growdon J, Hyman B. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Neursci. 1996;16:4491–500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04491.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris J, Price J. Pathologic correlates of nondemented aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;17:101–18. doi: 10.1385/jmn:17:2:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hulette CM, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Murray MG, Saunders AM, Mash DC, McIntyre LM. Neuropathological and neuropsychological changes in “normal” aging: Evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease in cognitively normal individuals. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:1168–74. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markesbery W, Schmitt F, Kryscio R, Davis D, Smith C, Wekstein D. Neuropathologic substrate of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:38–46. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:351–7. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roe CM, Fagan AM, Grant EA, Hassenstab J, Moulder KL, Maue Dreyfus D, et al. Amyloid imaging and CSF biomarkers in predicting cognitive impairment up to 7.5 years later. Neurology. 2013;80:1784–91. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918ca6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagan AM, Xiong C, Jasielec MS, Bateman RJ, Goate AM, Benzinger TL, et al. Longitudinal change in CSF biomarkers in autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Science translational medicine. 2014;6:226ra30. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blennow K, Dubois B, Fagan AM, Lewczuk P, de Leon MJ, Hampel H. Clinical utility of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blennow K, Hampel H. CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2003;2:605–13. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blennow K, Hampel H, Weiner M, Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nature reviews Neurology. 2010;6:131–44. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, Dubois B, Engelborghs S, Lewczuk P, Perret-Liaudet A, et al. The clinical use of cerebrospinal fluid biomarker testing for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: A consensus paper from the Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Standardization Initiative. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langbaum JB, Fleisher AS, Chen K, Ayutyanont N, Lopera F, Quiroz YT, et al. Ushering in the study and treatment of preclinical Alzheimer disease. Nature reviews Neurology. 2013;9:371–81. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampel H, Wilcock G, Andrieu S, Aisen P, Blennow K, Broich K, et al. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic trials. Progress in neurobiology. 2011;95:579–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC, Selkoe DJ. Recommendations for the incorporation of biomarkers into Alzheimer clinical trials: an overview. Neurobiology of aging. 2011;32(Suppl 1):S1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills SM, Mallmann J, Santacruz AM, Fuqua A, Carril M, Aisen PS, et al. Preclinical trials in autosomal dominant AD: implementation of the DIAN-TU trial. Revue neurologique. 2013;169:737–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, et al. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Science translational medicine. 2014;6:228fs13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fourier A, Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Quadrio I, Perret-Liaudet A. Pre-analytical and analytical factors influencing Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker variability. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2015;449:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattsson N, Zegers I, Andreasson U, Bjerke M, Blankenstein MA, Bowser R, et al. Reference measurement procedures for Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers: definitions and approaches with focus on amyloid beta42. Biomarkers in medicine. 2012;6:409–17. doi: 10.2217/bmm.12.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Annals of neurology. 2006;59:512–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:446–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, Zhou G, Snyder AZ, Marcus DS, et al. Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with FreeSurfer ROIs. PloS one. 2013;8:e73377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Marcus DS, Ances BM, et al. Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. NeuroImage. 2015;107:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutphen CL, Jasielec MS, Shah AR, Macy EM, Xiong C, Vlassenko AG, et al. Longitudinal Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Changes in Preclinical Alzheimer Disease During Middle Age. JAMA neurology. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Persson S, Carrillo MC, Collins S, Chalbot S, et al. CSF biomarker variability in the Alzheimer’s Association quality control program. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2013;9:251–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bittner T, Zetterberg H, Teunissen CE, Ostlund RE, Jr, Militello M, Andreasson U, et al. Technical performance of a novel, fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for the quantitation of beta-amyloid (1–42) in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2016;12:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]