Abstract

By February 2019, the Polish pharmaceutical industry, community and hospital pharmacies, wholesalers and parallel traders must all comply with the EU-wide Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD) legislation (2011/62/EU), to ensure that no medicinal product is dispensed to a patient without proper tracking and authentication. Here we describe how Poland is complying with the new EU regulations, the actions that have been taken to incorporate the FMD into Polish Pharmaceutical Law and whether or not these actions are sufficient. We found that Poland is only partially compliant with the FMD and further actions need to be undertaken to fully meet the Delegated Act (DA) requirements. Moreover, there is lack of awareness in Poland about the prevalence of falsified medication and the time scale required for implementation of the DA. Based on our findings, we suggest that a public awareness campaign should be started to raise awareness of the increased number of falsified medicines in the legal supply chain and that drug authorisation systems are implemented by Polish pharmacies to support the FMD.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, Counterfeit Drugs, Pharmacy Legislation, Pharmaceutical care, Pharmacy Service

EAHP Statement 1: Introductory Statements and Governance.

EAHP Statement 5: Patient Safety and Quality Assurance

Introduction

Falsified medicines pose a considerable hazard to the health and life of patients. The Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD) is an EU-wide legislative tool to protect public health across Europe.1 2 It ensures that only licensed pharmacies and approved retailers can offer medicines for sale, including internet sales. Implementation of the FMD is essential as it remains difficult to assess the number of falsified medicinal products present in the legal distribution chain and dispensed across the EU every day.

One of the EU's responsibilities is to maintain adequate healthcare and the wellbeing of citizens, while respecting the autonomy of member states in their individual health policies. Nevertheless, European law defines many significant aspects of medicinal product marketing, which are subsequently incorporated into the legal provisions in individual countries. One of the new legal instruments covering this topic is the Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011, amending Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community Code relating to medicinal products for human use, with regards to the prevention of the entry of falsified medicinal products into the supply chain. This legislation includes the definition of a falsified medicine and requires all 28 European countries to have a system in place to detect such medicines. Moreover, the FMD requires that many medicines are serially identified, protected by tamper-proof seals and their authenticity is verified before being dispensed to patients.1 2

On a national level, implementation of the EU-wide FMD legislation is being handled by a Delegated Act. On 19 December 2014, the Polish Pharmaceutical Act and certain other Acts (Dz. U. (Polish Journal of Laws) of 2015, item 28) were amended to introduce the definition of a falsified medicinal product and falsified active substance, which conforms to the definition proposed by the EU-wide FMD. The legislation assigned new tasks to the Main Pharmaceutical Inspectorate (pl. Główny Inspektor Farmaceutyczny, GIF), who will be provided with tools to ensure the quality and safety of medicinal products throughout manufacture, import and distribution of the active pharmaceutical ingredient.3

By August 2018, Poland must comply with the EU-wide FMD legislation (2011/62/EU), and community and hospital pharmacies will play an important role. Whereas community pharmacies in many other countries act as a public healthcare institution, under current Polish law they lack basic functionality, including a robust method to detect falsified medicines.4 Therefore, intensified and interdisciplinary action is needed on the part of the Polish government to ensure that we minimise hazards to the health and wellbeing of Polish patients. Here we describe how Poland is complying with the new EU regulations, the actions that have been taken to incorporate the FMD into Polish Pharmaceutical Law and propose some actions to ensure that we meet the August 2018 deadline.

Falsified medication in Poland: a threat to public health

In Poland, two major academic studies of counterfeit drugs have been published. The first study found that physicians and nurses working in hospitals in Poland are more aware of counterfeit medicines than laypeople and more often notice the presence of drugs from unknown sources.5 Moreover, nearly 90% of physicians, 80% of nurses and more than 40% of laypeople had heard about the possibility of importing illegal medicine from Ukraine or China.5 However, in the second study, healthcare professionals were found to have lower levels of awareness about the scale of counterfeit medicines, as well as the threats of counterfeit medicines to health, than laypeople.6

The quantity of falsified medicinal products appearing in the legal distribution chain in developed countries with effective systems of market control and market security is estimated to be about 1%.7 8 Considering the health risk posed by falsified medicines and the volume of drugs administered daily across Europe, this seemingly low prevalence could harm a vast number of patients. This phenomenon cannot be ignored, especially as the prevalence is estimated to be much higher at the eastern borders of Europe (∼10–20% in Russia and in former Soviet republics), and in African, Asian and South American countries, where falsified products amount to 30% of the legal market in some regions, with many of these products ending up in Western Europe.9 According to WHO and Interpol experts, Poland is at higher risk of falsified products entering the legal supply chain, due to its direct proximity to former Soviet bloc countries.10 Furthermore, trade occurs outside the legitimate sources of distribution, which cannot be accurately estimated. Indeed, in some countries—for example, the UK, the size of the legal and illegal markets for certain drugs has become almost equal.11 The geographical and geopolitical location of Poland is also particularly significant as the Polish border is an external border of the EU, thereby increasing the risk of illegal cross-border trade.

Cases of falsified medicines in Poland

Unfortunately, experts expect that the market for falsified drugs will expand.12 A recent WHO study showed that as many as half of dietary supplements contain substances that have not been listed on the packaging, which may enhance adverse effects in patients.13 For example, in 2009, a regional newspaper reported that a 20-year-old student from Tricity (pl. Trójmiasto) purchased tablets containing plant steroids on the internet, which resulted in the student becoming jaundiced.14 The causes of this symptom and the fate of the patient were not made known to the public.14 In some cases, chemical analysis showed that falsified medicinal products contain ingredients such as gypsum and dried grass.15

Police economic crime units seize thousands of falsified medicines every year. In Poland, the police launched 231 proceedings against illegal marketing of medicinal products in a 9-month period in 2011. Before 2011, there were about 350 cases of this kind a year. According to the police, illegal medicinal products mainly originate in Asia. In October 2010, as a result of the international police action, Operation Pangea IV, police seized more than 8700 medicinal products for erectile dysfunction, nearly 2 kg of hormones and steroids and more than 660 packages of dietary drugs.16 Approximately 65 000 packages, blisters, tablets, capsules, sachets, bottles and ampoules, as well as 70 kg of powdered substances (almost 9500 erectile dysfunction drugs and over 54 000 dietary supplements), were seized in 2011.17 In June 2011, police economic crime units detained three people suspected of dealing with medicines containing psychotropic substances imported illegally from the Czech Republic.17 One of the detainees was a citizen of Slovakia, who had smuggled 12 600 tablets of this medicine to customers all over the country. A month earlier, police in the Świętokrzyskie region detained a 22-year-old citizen of Gdańsk and seized 10 000 ampules of steroids found in his car.18

The internet remains the main outlet for purchasing falsified medicinal products; however, they can also be found in many market squares and outdoor marketplaces. However, to date, no formal analysis of falsified medication in the legal distribution chain has been performed in Poland. There is no consensus about the significance of falsified medication use among stakeholders in Poland.19

Legal sanctions for pharmaceutical crimes in Poland

Under Polish law, if an entity has been proved to have introduced a falsified medicinal product into the market, it is subject to administrative, civil and, most of all, criminal liability. Section 124b of the Pharmaceutical Act of 6 September 2001, directly refers to criminal liability: Whosoever manufactures a falsified medicinal product or a falsified active substance shall be subject to a fine, limitation of liberty or deprivation of liberty for a term of up to five years. Whosoever provides a falsified medicinal product or a falsified active substance or makes them available, whether for financial compensation or free of charge, or stores them for this purpose, is subject to the same penalty.20

Economic aspects of counterfeit product trade in Poland

Macroeconomic data analysis indicates that the counterfeit product trade will intensify in the coming years as a consequence of globalisation and harmonisation of markets. It is estimated that the counterfeit product trade constitutes about 9% of the entire global trade. The market of counterfeit goods in 2008 was valued as high as US$250 billion globally by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development,21 and the fastest growing counterfeit products include medicines and cosmetics, as well as wine and spirits. In 2011, the number of goods infringing property rights seized by customs officers in Poland increased from 1.9 to 4.7 million items compared with the corresponding period in 2010. In 2011, the value of seized counterfeit products was estimated at over PLN 100 million,22 which highlights the significance of this problem in Poland.

European agencies as guardians of compliance with pharmaceutical law

Each member state makes it a priority to protect the health of its citizens, which is also the priority of the entire EU. Agencies and regulators must counteract the dissemination of falsified medicinal products to reduce the public health risk, increase patient trust in the national healthcare system and maintain the professional image of its representatives. Therefore, both the European Medicines Agency, which regulates the registration of medicinal products, and the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM) have placed high importance on regulating falsified medicinal products. Despite being partly autonomous, the EDQM answers to the Council of Europe and its tasks include the protection of public health in the EU through the development, support, introduction and monitoring of quality standards for medicines and their safe use.23 As a result of EDQM's activities, the Counterfeit/Illegal Medicines Working Group came into existence and implemented the market surveillance scheme in only two sessions in 2012. Special attention should also be paid to the first session of technical training organised jointly by the EDQM and its Polish member, the National Medicines Institute (NIL), which took place on 4 and 5 September 2012, in Warsaw. Positive feedback from the participants enabled the programme to be continued in 2013. The proposal for closer cooperation with other authorities (such as customs control, the police and state healthcare institutions) has also been positively evaluated.24

Introduction of changes into the Polish pharmaceutical system

The proposed solutions that generate costs include the following: increasing the number of pharmaceutical inspectors; increasing regular inspections of manufacturers' importers and distributors; expanding the EudraGMP database (EudraGMP is the name for the Union database referred to in article 111(6) of Directive 2001/83/EC and article 80(6) of Directive 2001/82/EC, containing information, for example, on manufacturing and import authorisations or good manufacturing practice (GMP) certificates); introduction of an electronic system of registration of manufacturers, importers and distributors; issuing certificates of good distribution practice; training current inspectors; and adapting the electronic system of the GIF.

On 8 January 2015, the amended Pharmaceutical Act was announced (the Act of 19 December 2014 on the amendment of the Pharmaceutical Act and certain other acts) and most of the amendments proposed by this statute came into force 30 days later. The new legal provisions introduced the definition of a falsified medicinal product and the previously unknown institution of the wholesale agent for medicinal products and specified the requirements for the wholesale and retail marketing of medicinal products. Moreover, the Act introduced the requirements for the manufacture, import and marketing of active substances, which is connected with GMP and is very important for the pharmaceutical industry.25

The amended legal provisions (including those to be introduced in the future) aim to create a tightly supervised system for the distribution of medicinal products, from the manufacturer, wholesale and retail agents, to the final consumer. In line with the intention of the legislation, a system of protective measures should be created to enable the verification of authenticity and identification of packaging and to find proof of potential violations. In principle, the system will be mandatory for all prescription medicinal products and some over-the-counter medications at higher risk of falsification.26

The Association of the Innovative Pharmaceutical Industry Employers in Poland (pl. INFARMA) has estimated the costs of the introduction of the European FMD into the Polish pharmaceutical industry. According to its calculations, adaptation of the production lines alone will amount to at least €48 million.26 The Association of Polish Pharmaceutical Wholesale Employers (pl. Związek Pracodawców Hurtowni Farmaceutycznych) reacted negatively to the proposed changes, stating that the distribution of reimbursed drugs is unprofitable even now and wholesalers lose money when storing the reserves.26 Therefore, there will be some major hurdles when implementing the FMD in Poland over the coming years.

Implementation of drug authorisation systems into Polish pharmacies

To verify the authenticity of all prescription and over-the-counter medicines in Europe is an immense undertaking. Manufacturers, pharmacies and patients must all be linked using multiple national databases. The pharmacist's role in providing pharmaceutical care services cannot be overestimated. From 2019, pharmacies will become the final point of medicine verification in Poland and would benefit from being supported by electronic dispensing systems or patient medical records, which currently do not exist in Poland and are required to provide care similar to that in other countries.27 28 The Pharmaceutical Act and the Act on Pharmaceutical Chambers define the scope of pharmaceutical services provided by Polish pharmacists. Section 2a of the Act on Pharmaceutical Chambers stipulates that: The pharmacist profession aims at protecting public health and includes the provision of pharmaceutical services, including, in particular, the provision of information about medicinal products and medical devices. 29 30 Section 86 of the Pharmaceutical Act, however, stipulates that the word ‘pharmacy’ is reserved solely for the place where pharmaceutical services are provided, including the provision of information and advice on the effects and application of medicinal products and medical devices marketed in pharmacies and pharmaceutical wholesalers. Providing thorough information about the drug, as well as dispensing the appropriate medication, are elements of pharmaceutical care.

If there were appropriate investment in the development and implementation of a medicinal product authorisation system, paid for by the pharmaceutical manufacturing companies in Poland, pharmacies would be able to fully guarantee that the proper, original product is dispensed to the patients, thus improving pharmaceutical care. Moreover, an authorisation system eliminates the possibility that a falsified substance or medicinal product enters the supply chain. Since safe pharmacotherapy is one of the elements of pharmaceutical care, which is in line with the guidelines published by the EDQM, the introduction of a drug authorisation system into the Polish market is an unquestionable priority for legislators and all institutions related to the marketing of medicinal products.26

Team for Falsified Medicinal Products in Poland

Polish government agencies have undertaken legal action in response to the hazards connected with falsified medicinal products. The main task is to coordinate the actions of various entities in order to increase their efficiency and effectiveness. On 9 November 2007, at the motion of the GIF, the Minister of Health issued an order forming the interministerial Team for Falsified Medicinal Products (Dz. Urz. MZ (Journal of Laws of the Ministry of Health) of 2007, No. 17, item 92).31 The GIF was the team's chairperson and other team members included representatives from the Ministry of Health; the President of the Office for Registration of Medicinal Products, Medical Devices and Biocidal Products; the Chief Sanitary Inspector; the State Public Prosecutor; the Chief Police Commander; the Head of Customs; and the Director of the NIL.

Because the problem had intensified, on 9 September 2010, the Minister of Health issued an order replacing the existing team with the intraministerial Team for Falsification and Illegal Trade of Medicinal Products and Other Falsified Products Meeting the Criteria for Medicinal Products (Dz. Urz. MZ (Journal of Laws of the Ministry of Health) of 2010 No. 11, item 67). In line with the above order, the team was joined by representatives of the President of the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection and the Chief Veterinarian. The team includes: the GIF (chairperson), GIF representatives (deputy chairperson and secretary) and nine other members, appointed by (among others) the President of the Office for Registration of Medicinal Products, Medical Devices and Biocidal Products (pl. Urząd Rejestracji Produktów Leczniczych I Wyrobów Medycznych I Produktów Biobójczych).32 The team's tasks also expanded and its performance should ensure the implementation of effective solutions restricting the falsification of medicinal products. Currently, the team's tasks include minimising the practice of marketing falsified medicinal products, including marketing drugs in unauthorised places, and other falsified products meeting the criteria of medicinal products due to the undeclared content of active substances (see table 1). The new tasks also include planning and implementing activities that disseminate information on falsified medicinal products and medicines coming from illegal sources and public awareness campaigns on the risks related to purchasing medicinal products in unauthorised places.31

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Team for Falsification and Illegal Trade33

| Topics | Details |

|---|---|

| Health security | Analysing and evaluating the conditions for, and determining the consequences of, falsifying medicinal products, selling drugs in unauthorised locations and selling other falsified products meeting the criteria for medicinal products, with particular focus on society's health security |

| Pharmaceutical inspectorate | Informing the Main Pharmaceutical Inspectorate (GIF) of the discovery of falsified medicines, medicinal products from illegal sources and other falsified products meeting the criteria for medicinal products for the purpose of adding them to the database maintained on the GIF’s website |

| Public debate | Running public educational campaigns on the risks of purchasing medicinal products in unauthorised locations |

GIF, Główny Inspektor Farmaceutyczny.

National Medicines Verification Organisation in Poland

In line with the European Medicines Verification Organisation (EMVO) guidelines, local units of the organisation (ie, National Medicines Verification Organizations, NMVOs) should have been created by 27 May 2015. However, the Polish NMVO, which was planned to be formed in March 2016, remains to be established. The process of NMVO creation is clearly described in the brochure published by the EMVO. One of the basic characteristics of the national process should be transparency of the public debate. The process of shaping the management board, as well as the recruitment of individuals and organisations included in the NMVO, must be in line with EMVO guidelines.

For the role of non-profit legal entities in the framework of the Polish legal system, it should be emphasised that the NMVO in Poland will be formed of the following parties: INFARMA (pl. Związek Pracodawców Innowacyjnych Firm Farmaceutycznych)—local EFPIA; PZPPF (pl. Polski Związek PracodawcówPrzemysłu Farmaceutycznego)—local EGA; SIRPL (pl. Stowarzyszenie Importerów Równoległych Produktów Leczniczych)—local EAEPC. Currently, the National Pharmacy Chamber (ie, PGEU) as well as ZPHF (pl. Związek Pracodawców Hurtowni Farmaceutycznych)—local GIRP are not the part of the NMVO working group. According to the EMVO road map and PGEU requirements the National Pharmacy Chamber should be part of the NMVO, which is currently not the case. Moreover, ZPHF—local GIRP (GIRP, the European Healthcare Distribution Association; more information: http://www.girp.eu/) is also not part of the NMVO. In summary, the non-profit entities have a limited role in the process of establishing the national repository system in Poland, despite the requirements contained in the European legislation framework.

Public campaign on falsified medication

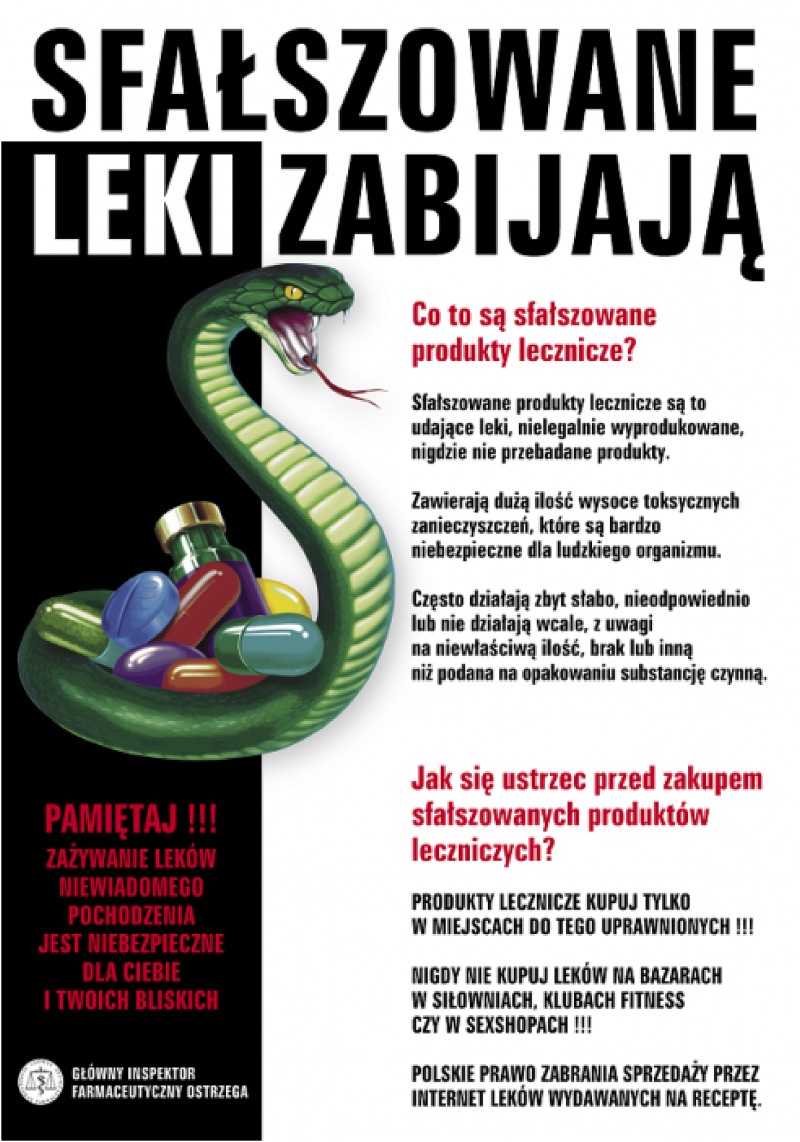

The Polish GIF, together with other agencies, started a campaign to inform the public about the risks of using counterfeit medication. Important information for the patient can be found, as well as other information, on the GIF website.7 34 In addition to key definitions and frequently asked questions, pharmacists can find material such as posters and leaflets. One poster bears a ‘Falsified Drugs Kill’ slogan accompanied by snake graphics (figure 1). The website indicates that the most frequently falsified medicinal products are anabolic steroids, slimming products and drugs for erectile dysfunction.34 According to the GIF, the medicinal products available in retail and hospital pharmacies, as well as drug dispensaries are safe, which in our opinion is not entirely true and may lower patients' vigilance. Indeed, a growing number of falsified medicines have also been found in the legal market and prevention of this is one of the challenges that legislators must face.34 Similar information can be found on the Ministry of Health website.32 A public campaign that highlights the increasing number of falsified medicines in the legal supply chain is important for creating awareness and ensuring compliance with the European FMD.

Figure 1.

Falsified drugs kill—a poster available on the main pharmaceutical inspectorate’s website.

Recommendations for pharmacists—the question is still open

Implementation of the FMD is a great challenge in Poland, where the role of hospital and community pharmacists is limited to dispensing medicines. Cognitive pharmaceutical services and clinical pharmacy are not widespread. Implementation of the FMD is an opportunity to promote new services into routine practice and to broaden the concept of pharmaceutical care.35

Introduction of the FMD in Polish hospital pharmacies will be more difficult than in community pharmacies. Consequently, hospital managers need to be familiar with the new legislation framework.36

Moreover, the Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/161 introduced technical details that will affect dispensing procedures in Polish hospitals. Transfer of medicinal products between hospitals is frequent and unavoidable in emergencies. Article 25, (2) states the following: “a healthcare institution may carry out that verification and decommissioning at any time the medicinal product is in the physical possession of the healthcare institution, provided that no sale of the medicinal product takes place between the delivery of the product to the healthcare institution and the supplying of it to the public”. This may introduce complications for hospital pharmacists. Moreover, article 13 (b) states clearly that the medicinal products might be returned to hospital pharmacies and if they are not returned from the ward in <10 days can only be used in the hospital that decommissioned the product. Before full implementation of the FMD, detailed operational procedures should be prepared and pharmacists educated further. Another problem is associated with the pre-package of medicinal products in a hospital—for example, a unit dose dispensing system; however, this service is limited to only a few hospitals in Poland. When a hospital pharmacist supplies part of a pack, decommissioning of the unique identifier needs to occur when the pack is opened for the first time as stated in article 28.37 38

Hospital pharmacists should bear in mind the implications of the FMD. Publications refer to the different locations in the hospital pharmacy where decommissioning can happen and the consequences of choosing one stage rather than another. Pharmacists should analyse their workflow and the dispensing operations to facilitate FMD legislation.

Also, they should identify products that will not require decommissioning. For example, large infusions and contrast media are good examples of medicinal products that do not legally require the unique identifier safety features; a full list was introduced within the delegated regulation annexes. Standard operations procedures should also be adopted to ensure good authentication practices.4

In summary, the implementation of the FMD in Poland is still an open question. Direct cooperation between academic and non-academic institutions is strongly recommended, particularly in the preparation of solutions and procedures associated with the technical problems mentioned above.

Conclusions

Incorporation of European legislation into the Polish legal system will continue to contribute to changes in pharmaceutical practice, improving standards and safety for all patients. However, Poland is only partially compliant with the FMD and further action should be undertaken to meet the requirements of the Delegated Acts. Moreover, based on current literature, an accurate study evaluating the percentage of counterfeit/falsified medication in Poland should be performed. We emphasise that public campaigns must also provide awareness of the potential for falsified medicines to be found in the legal supply chain. We also encourage the investment into, and implementation of, drug authorisation systems in Polish pharmacies to support the FMD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Graham Smith and Mark De Simone from Aegate Ltd for their contribution and support during the preparation of our paper. We express our sincere appreciation and thanks to the following organisations for providing their help and guidance at every stage of our research: the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (UK), Polish National Pharmaceutical Chamber (Poland) and the Polish Pharmaceutical Society (Poland). We also thank Regis Vaillancourt (pharmacy director), Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) Pharmacy, 401 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada for expertise and pointing out the most important aspects from the perspective of the International Pharmacy Federation (FIP).

Footnotes

Contributors: PM and DŚ designed the paper, collected and analysed the data and drafted the paper. MB, MD and KK collected the data and revised the manuscript. MJ, DAB and BDN supervised the paper and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors had complete access to the study data that supported the publication. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: It must be emphasised that this publication was created purely for practice and academic interest and must not be construed in any way as an investment recommendation. PM is a research assistant at the Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Ludwig Rydygier Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz and is a current employee of Aegate Ltd in Poland (since 1 June 2015). DAB is an employee of Aegate Ltd; a stockholder in IP Assett Ventures and Translation Ventures Ltd (Charlbury, Oxfordshire, UK), a company that among other services provides cell therapy biomanufacturing, regulatory and financial advice to clients in the cell therapy sector.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Smith G, Smith JA, Brindley DA. The Falsified Medicines Directive: how to secure your supply chain. J Generic Med 2014;11:169–72. 10.1177/1741134315588986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taaffe T. European Union has the Falsified Medicines Directive. BMJ 2012;345:e8356 10.1136/bmj.e8356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Changes in pharmaceutical law that will come into effect per month] Za miesiąc wejdą w życie zmiany w prawie farmaceutycznym (in Polish) [Newsletter Article]. Poland (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.zdrowie.abc.com.pl/czytaj/-/artykul/za-miesiac-wejda-w-zycie-zmiany-w-prawie-farmaceutycznym.

- 4. Naughton BD, Smith JA, Brindley DA. Establishing good authentication practice (GAP) in secondary care to protect against falsified medicines and improve patient safety. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract 2016;23:118–20. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2015-000750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Binkowska-Bury M, Wolan M, Januszewicz P, et al. . What Polish hospital healthcare workers and lay persons know about counterfeit medicine products? Cent Eur J Public Health 2012;20:276–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Binkowska-Bury M, Januszewicz P, Wolan M, et al. . Counterfeit medicines in Poland: opinions of primary healthcare physicians, nurses and lay persons. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:559–68. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04166.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. [Facts—Falsified medicinal products—Main Pharmaceutical Inspectorate] Fakty—Sfałszowane produkty lecznicze (in Polish) Poland (cited 4 January 2016). https://www.gif.gov.pl/pl/nadzor/sfalszowane-produkty-le/informacje-ogolne/sfalszowane-produkty-le/479,Fakty.html.

- 8.Medicines W. Counterfeit Medicines (cited 12 December 2015). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs275/en/

- 9. Fayzrakhmanov NF. Fighting trafficking of falsified and substandard medicinal products in Russia. Int J Risk Saf Med 2015;27(Suppl 1):S37–40. 10.3233/JRS-150681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fijałek Z, Sarna K. [Some quality aspects of medicinal products and dietary supplements—substandard, illegal and counterfeit products] Wybrane aspekty jakości produktów leczniczych i suplementów diety—produkty substandardowe, nielegalne i sfałszowane (in Polish). Rynek Farmaceutyczny 2009;65:467–75. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fijałek Z, Sarna K, Błazewicz A, et al. . [Counterfeit phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors—growing safety risks for public health] (in Polish). Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2010;61:227–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. WHO. Growing threat from counterfeit medicines. Bull World Health Organiz 2010;88:241–8. 10.2471/BLT.10.000410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.2013. [Drugs from the internet: up to 90 percent are “fake”] Leki z internetu: nawet 90 proc. to “fałszywki (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.rynekzdrowia.pl/Farmacja/Leki-z-internetu-nawet-90-proc-to-falszywki,135898,6.html.

- 14. [Herbs from the internet lead to jaundice] Ziółka z internetu zaraziły go żółtaczką (in Polish) 2009. (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.rynekzdrowia.pl/Farmacja/Ziolka-z-internetu-zarazily-go-zoltaczka,9854,6.html.

- 15.2009. [Gypsum and dried grass—such a “drug” buy Poles from scammers] Gips i suszona trawa—takie “leki” kupują Polacy od oszustów (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.rynekzdrowia.pl/Farmacja/Gips-i-suszona-trawa-takie-quot-leki-quot-kupuja-Polacy-od-oszustow,13392,6.html.

- 16.2010. [Be careful of fake drugs!] Uważajmy na sfałszowane leki! (in Polish) Poland. (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.policja.pl/pol/aktualnosci/60550,Uwazajmy-na-sfalszowane-leki.html.

- 17.2011. [The police seized contraband] Policjanci przejęli kontrabandę (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.policja.pl/pol/aktualnosci/66968,dok.html.

- 18.2011. [Carrying 10,000 ampoules of steroids] Przewoził 10 tysięcy ampułek ze sterydami (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.policja.pl/pol/aktualnosci/65720,dok.html.

- 19.Baczykowska A.2014. Implementation of the falsified medicinal products directive into Polish pharmaceutical law. (cited 9 January 2016). http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=d7733c55-cfa1-4f32-9305-904a80c61ea5.

- 20.2015. [Combating counterfeiting of medicinal products] Zwalczanie fałszowania produktów leczniczych (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.infor.pl/prawo/prawa-konsumenta/prawa-pacjenta/702046,3,Zwalczanie-falszowania-produktow-leczniczych.html.

- 21. OECD. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—Magnitude of counterfeiting and piracy of tangible products: an update 2009. (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/57/27/44088872.pdf

- 22.2014. [Authentication products—solutions in the fight against counterfeiting] Autentykacja produktowa—rozwiązania w walce z podróbkami (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.logistyka.net.pl/bank-wiedzy/wiesci-z-gs1/item/86373-autentykacja-produktowa-rozwiazania-w-walce-z-podrobkami.

- 23. GS1 Healthcare Conference Lisbon (October 23–25) EDQM activities around counterfeiting and traceability, 2012.

- 24. EDQM. European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare Annual Report, 2012.

- 25.2015. [Life Sciences Law Blog—The amendment to the Pharmaceutical Law will soon enter into force] Nowelizacja Prawa farmaceutycznego wkrótce wejdzie w życie (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://blog.dzp.pl/pharma/nowelizacja-prawa-farmaceutycznego-wkrotce-wejdzie-w-zycie-2/

- 26.2014. [Modification of the Pharmaceutical Law: a dark cloud over the industry again?] Modyfikacja Prawa farmaceutycznego: znowu czarne chmury nad branżą? (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.rynekaptek.pl/prawo/modyfikacja-prawa-farmaceutycznego-znowu-czarne-chmury-nad-branza,5921_5.html.

- 27. Łasocha P, Merks P, Olszewska A. [Hospital and clinical pharmacy in the United Kingdom] Farmacja szpitalna i kliniczna w Wielkiej Brytanii (in Polish). Farm Pol 2013;69:527–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Merks P, Piekart E, Krupa K, et al. . [Patient medical records (PMR) as an important aspect of documenting pharmaceutical care] Dokumentacja medyczna pacjenta (DMP) jako istotny czynnik w aspekce wdrażania opieki farmaceutycznej (in Polish). Farm Pol 2013;69:464–74. [Google Scholar]

- 29. EDQM. Pharmaceutical care: where do we stand—where should we go? European Directorate of Quality of Medicines (EDQM), Survey Report 2009—Key concepts in pharmaceutical care, quality assessment of pharmaceutical care in Europe and sources of information, 2009.

- 30. Act of April 19, 1991, on pharmaceutical chambers. Dz. U. [Journal of Laws] of 2008, No. 136, as amended.

- 31. [Team for falsified medicinal product—Main Pharmaceutical Inspectorate] Zespół ds. Sfałszowanych Produktów Leczniczych (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). https://www.gif.gov.pl/pl/nadzor/sfalszowane-produkty-le/zespol-ds-sfalszowanyc/103,Zespol-ds-Sfalszowanych-Produktow-Leczniczych.html.

- 32. [Polish Ministry of Health—falsified medicinal products] Sfałszowane produkty lecznicze (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). http://www.mz.gov.pl/leki/produkty-lecznicze/sfalszowane-produkty-lecznicze.

- 33. Order of the Minister of Health of September 9, 2010, on appointing the Team for Falsification and Illegal Trade of Medicinal Products and Other Falsified Products Meeting the Criteria for Medicinal Products (Dz. Urz. MZ [Journal of Laws of the Ministry of Health] of 2010 No. 11, item 67).

- 34. [Frequently asked questions—Main Pharmaceutical Inspectorate] Najczęściej zadawane pytania (in Polish) (cited 4 January 2016). https://www.gif.gov.pl/pl/nadzor/sfalszowane-produkty-le/najczesciej-zadawane-p/104,Najczesciej-zadawane-pytania.html.

- 35. European Union. Directive 2011/62/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 amending Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relating to medicinalproducts for human use, as regards the prevention of the entry into the legal supply chain of falsified medicinal products. Official J Eur Union 2011;74:74–87. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naughton BD, Vadher B, Smith J, et al. . EU Falsified Medicines Directive mandatory requirements for secondary care: a concise review. J Generic Med 2016;12:95–101. 10.1177/1741134316643358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/161 of 2 October 2015 supplementing Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council by laying down detailed rules for the safety features appearing on the packaging of medicinal products for human use 2015. (cited 5 May 2016). http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2016:032:FULL&from=EN (accessed 12 May 2016).

- 38. Berman B. Strategies to detect and reduce counterfeiting activity. Bus Horiz 2008;51:191–9. 10.1016/j.bushor.2008.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]