Abstract

Background

Lipid and glycemic abnormalities are prevalent in diabetes leading to long term complications. Use of safe and natural foods instead of medications is now considered by many scientists.

Objectives

This study aimed at determining the effect of ginger on lipid and glucose levels of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

In a double‐blind placebo-controlled trial, 50 patients with type 2 diabetes were randomly allocated to 2 groups of intervention (n = 25) and placebo (n = 25). Each patient received 2000 mg per day of ginger supplements or placebo for 10 weeks. Serum levels of fasting blood sugar (FBS), total cholesterol (TC), triacylglycerol (TG), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) were analyzed. Daily dietary intakes and anthropometric parameters were also determined.

Results

Data from 45 patients were analyzed (23 patients in the ginger group and 22 patients in the control group) at the end of the study. Ginger consumption significantly reduced serum levels of fasting blood glucose (-26.30 ± 35.27 vs. 11.91 ± 38.58 mg/dl; P = 0.001) and hemoglobin A1C (-0.38 ± 0.35 vs. 0.22 ± 0.29 %; P < 0.0001) compared to the placebo group. Ginger consumption also reduced the ratio of LDL-C/HDL-C (2.64 ± 0.85 vs. 2.35 ± 0.8; P = 0.009). However, there was no significant change in serum concentrations of triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL-C, and HDL-C due to the ginger supplements.

Conclusions

The current results showed that ginger could reduce serum levels of fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: Ginger, Type 2 Diabetes, Blood Sugar, HbA1C, Lipid Parameters

1. Background

Diabetes mellitus is defined as a metabolic disorder with chronic hyperglycemia and metabolic dysfunction of macronutrient, which is induced by deficiency in insulin secretion, function, or both (1). Reportedly, the incidence of diabetes was 382 million people worldwide, during year 2013 (2). Furthermore, 2 million adults (7.7%) aged 25 to 64 years had diabetes in Iran, during year 2008. Also, 4.4 million (16.8%) Iranian adults had impaired fasting glucose (3). Diabetes leads to microvascular and macrovascular complications with a huge burden (4).

Currently, oral hypoglycemic agents, insulin, and diet are employed for the treatment of diabetes (5). On the other hand, synthetic anti-diabetic drugs have serious side effects such as hypoglycemic coma and liver-kidney disorders (6). The world health organization (WHO) recommends the use of medicinal plants of food items for the treatment of diabetes mellitus (7).

Ginger with the scientific name of Zingiber officinale is the most widely consumed spice around the world, including Iran. It is used for the treatment of diseases such as arthritis, rheumatism, diseases of the nervous system, inflammation of the gums, tooth pain, asthma, constipation, and diabetes for more than 2,500 years in traditional medicine (8).

Volatile oils and non-volatile pungent compounds are the main chemical constituents of ginger rhizome (9). The volatile oil constituents of ginger are composed of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, mainly zingiberene (35%), curcumene (18%), and farnesene (10%), with a small amount of bisabolene, b-sesquiphellandrene, and monoterpenoid hydrocarbons (10). The non-volatile pungent contains biologically active components, such as gingerols, shogaols, parasols, and zingerone, which produce a ‘‘hot’’ sensation in the mouth (10), and are known to have anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, antioxidant, and anti-cancer activities (11, 12).

There are scientific evidences about the effects of ginger on fasting blood sugar and lipid profiles. Mahluji et al. (2013) reported that the consumption of 2 g of ginger in patients with type 2 diabetes for 2 months reduces insulin, homeostasis model assessment (HOMA), Triglyceride (TG) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), with no impact on Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG), HbA1C, total cholesterol, and HDL levels (13). Moreover, Bordia et al. (1997) showed that the consumption of 4 g of ginger powder for 3 months has no significant change in healthy subjects, or patients with cardiovascular disease (CAD) or patients with type 2 diabetes with or without CAD (14).

Due to conflicting findings, the aim of this study was to determine the effect of ginger consumption on blood glucose, HbA1C, and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population and Intervention

This double‐blind placebo-controlled trial study was performed on patients with type 2 diabetes, who were referred to Ziaeian hospital of Tehran. Patient recruitment was started in June 2015 and ended in January 2016. All of the 50 males and females with type 2 diabetes were enrolled. No matching was performed in this study. The randomization methods for assigning patients to intervention and control groups were “permuted randomized block design”. The sample size was calculated in order to detect 15 mg/dL difference in mean fasting blood sugar due to ginger supplementation. Statistical power was considered as 0.90 and α = 0.05, and sample size was estimated as 21 in each group (8). Fifty patients with type 2 diabetes (30 to 60 years old) were included after the baseline assessments. Inclusion criteria were presence of type 2 diabetes between 1 and 10 years, treatment with oral hypoglycemic medications, and body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 35 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria were considered as pregnancy and lactation, usage of tobacco or alcohol, autoimmune disorder, cardiac ischemic or renal disease, thyroid or chronic inflammatory disease, regular consumption of ginger or other herbal medications or consumption of supplements such as vitamin C, E, and omega-3 during the 1 month prior to the study, consumption of less than 90% of ginger capsules, self-reported sensitivity to ginger consumption, and change of patient’s routine treatment.

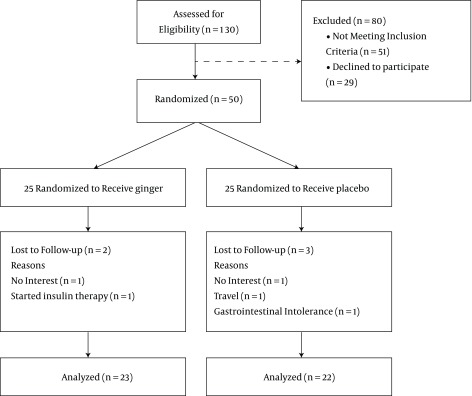

After attending the orientation session and fulfilling written informed consent papers, the patients were randomly allocated to 2 groups receiving ginger or placebo. People in the intervention group consumed 2000 mg of grinded ginger and the control group consumed placebo capsules containing wheat flour. Two 500-mg capsules were taken before lunch and 2 before dinner, daily for 10 weeks. All patients in the 2 groups were permitted to consume their routine medications according to their physician’s recommendation. The patients were advised not to change their regular diet or physical activity during the study period. Patients were informed about the benefits and possible risks of the study and were free to withdraw from the study at any time during the trial for any reason. In the follow-up period, patients were phoned once a week to increase their adherence to the study protocol. During the intervention, 2 patients in the ginger group (1 due to unwillingness to cooperation, and 1 due to starting insulin therapy) and 3 patients in the placebo group (1 due to unwillingness to cooperate, 1 due to travel, and 1 due to gastrointestinal intolerance) were excluded from the study. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in advance by IR TUMS.REC.1394.38 number and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with reference number NCT02666807.

2.2. Supplement Preparation

Supplements were purchased from Bou-Ali Sina Co. (Ghom, Iran). Placebo capsules were prepared in the same appearance by Bou-Ali Sina Co. (Ghom, Iran).

2.3. Measurements

Body weight was measured in the fasting state with light clothing and no shoes using a Seca scale (Seca, Hamburg, Germany). Height was measured without shoes using a stadiometer attached to the scale. Body mass index was computed as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Blood pressure was measured by a digital sphygmomanometer (SANITAS, Germany) after a 15-minute rest in sitting position. Daily intake of energy, macronutrients, and fiber were estimated using 24-hour dietary recall questionnaire for 3 days at the beginning and the end of the intervention. Nutritionist IV software version 3.5.2 (the Hearst Corporation, San Bruno, CA) was employed to analyze 3-day averages of dietary recall data. The levels of physical activity were obtained through interview with individuals using the International physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) at the beginning and the end of the study.

2.4. Clinical and Biochemical Analysis

Blood samples (10 mL) were taken after 12 to 14 hours of fasting state at the beginning and after 10 weeks of intervention. The centrifugation of the samples was performed at room temperature and at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate serum from blood cells. Fasting serum glucose, TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL, and HbA1c were determined by the enzymatic colorimetric method with commercial kits (Pars Azmun Co., Tehran, Iran) on an automatic analyzer (Abbott, model Alcyon 300, Abbott Park, IL).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Normal distribution of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Independent t test or Mann-Whitney test were employed to compare the 2 groups at baseline and the end of the study. Quantitative data before and after treatment within each group were compared using paired t test or Wilcoxon test. Qualitative data were analyzed using Chi square tests. Data are presented as mean (± SD) and frequency (percentage) for quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively. The significance level was set at P-value equal or less than 0.05.

3. Results

One hundred and thirty patients with type 2 diabetes were assessed for eligibility before the intervention. Fifty-one people were excluded and 29 were declined before randomization. Fifty patients with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to either the intervention (n = 25) or control group (n = 25). The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart for Screening and Enrolment of Participants.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are reported in Table 1. There was no significant difference in anthropometrics, blood pressure, and biochemical variables between the groups. Comparisons showed no statistical difference in age, gender proportion, and physical activity at baseline between the 2 groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Participantsa.

| Ginger (n = 25) | Placebo (n = 25) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 51.7 ± 8.5 | 49.6 ± 8.6 | 0.40 |

| Male, % | 34.8 | 27.3 | 0.58 |

| Physical activity, % | |||

| Light | 39.1 | 36.4 | 0.87 |

| Moderate | 52.2 | 50.0 | |

| Sever | 8.7 | 13.6 | |

| Body weight, kg | 78.4 ± 11.7 | 76.7 ± 14.2 | 0.67 |

| BMI, kg /m 2 | 29.9 ± 3.5 | 29.2 ± 4.6 | 0.56 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 121 ± 16.0 | 115 ± 14.7 | 0.20 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 74.5 ± 13.3 | 72.9 ± 9.3 | 0.64 |

| FBS, mg/dL | 170 ± 74.8 | 161 ± 49.0 | 0.63 |

| HbA1c | 7.30 ± 1.90 | 7.50 ± 2.03 | 0.73 |

| TG, mg/dL | 147 ± 72.8 | 149 ± 68.4 | 0.91 |

| TC, mg/dL | 175 ± 43.3 | 171 ± 47.5 | 0.79 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 41.5 ± 7.45 | 42.2 ± 7.50 | 0.75 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 108 ± 37.6 | 106 ± 40.8 | 0.90 |

| LDL-C to HDL-C ratio | 2.64 ± 0.85 | 2.58 ± 0.99 | 0.84 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD unless stated otherwise (independent t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for dichotomous variables was used.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol

There was no significant difference in dietary intakes of the participants at baseline and after treatment, between the groups (data not shown).

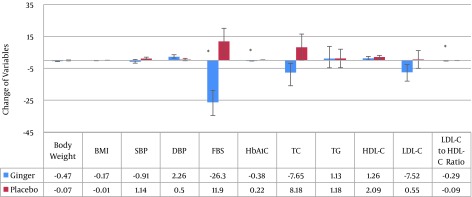

Variables after treatment in both groups are shown in Table 2. In Figure 2, mean (SE) change of the variables in both ginger and placebo groups are presented. There was a significant decrease of FBS in the ginger group after the intervention (P = 0.002). Meanwhile, the mean variation of HbA1C was similar to that of FBS (P < 0.001).

Table 2. Study Variables in the Ginger and Placebo Groups at the End of Interventiona.

| Ginger (n = ) | Placebo (n = ) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, kg | 77.9 ± 11.2 | 76.7 ± 14.0 | 0.74 |

| BMI, kg /m 2 | 29.7 ± 3.3 | 29.2 ± 4.5 | 0.64 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 120 ± 14.7 | 117 ± 13.8 | 0.36 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 76.8 ± 11.1 | 73.4 ± 8.1 | 0.25 |

| FBS, mg/dL | 144 ± 65.3 | 173 ± 63.9 | 0.14 |

| HbA1c | 6.92 ± 1.93 | 7.72 ± 2.08 | 0.18 |

| TG, mg/dL | 148 ± 66.9 | 151 ± 70.9 | 0.90 |

| TC, mg/dL | 167 ± 45.2 | 179 ± 41.2 | 0.34 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 42.8 ± 7.8 | 44.3 ± 8.60 | 0.53 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 100 ± 42.1 | 107 ± 34.3 | 0.57 |

| LDL-C to HDL-C ratio | 2.35 ± 0.80 | 2.49 ± 0.81 | 0.55 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD (independent t-test was used).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol

Figure 2. Mean (SE) Change of the Variables in Both Ginger and Placebo Groups.

* P < 0.05 (significant change compared to baseline values; Paired sample t test was used).

The researchers did not identify a significant difference in the mean TG, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and LDL-C in the ginger group before and after the intervention, whereas, a significant decrease was found in the LDL/HDL ratio (P = 0.009) due to ginger consumption. However, the mean difference in lipid profile was not significant between the 2 groups before and after the intervention.

4. Discussion

Results of the present study showed that daily consumption of 2000 mg of ginger reduced FBS, HbA1C, and LDL/HDL ratio in 10 weeks. Oludoyin et al. (2014) found that consumption of ginger extract, both raw or cooked, reduced fasting blood glucose to normal levels as effectively as treatment with anti-diabetic medication, glibenclamide (15). The mentioned study is consistent with the FBS results of the current study. In a study by Kazeem et al. it was shown that the consumption of 500 mg/kg body weight of free or bound polyphenol extracts of Zingiber officinale for 28 days reduced fasting blood glucose of diabetic rats (16), which is also consistent with the current study. In another study conducted by Ozougwu et al. (2011), a dose-dependent significant reduction in the blood glucose, total serum lipid and total serum cholesterol was reported in rats (17). Al-Amin et al. (2006) also demonstrated that 500 mg/kg aqueous extract of raw ginger causes a significant decrease in serum glucose, cholesterol, and triacylglycerol levels in the ginger-treated diabetic rats, therefore, being in line with the FBS results, yet inconsistent with the results on lipid profiles (18). Another research indicated that consuming 1600 mg of ginger for 12 weeks, significantly reduces fasting plasma glucose, HbA1C, insulin, HOMA, triglyceride, and total cholesterol compared to the placebo group, however, there were no significant difference in HDL and LDL (19). This study is in the same line with FBS, HbA1C, HDL and LDL results, yet, inconsistent with the current results on triglyceride and total cholesterol. Bordia et al. (1997) reported that the consumption of larger dose of ginger (4 g of ginger powder) for a longer time period (3 months) was not effective on lipids or blood sugar in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), or diabetic patients (with or without CAD) (14). Contradictory results in the current study with these studies may be due to differences in the response of patients, differences in the duration of diabetes, the dose of intervention or type of supplements. Most articles did not mention the type and dose of patient’s lipid lowering medications.

However, the exact mechanism is unknown; some mechanisms are suggested as ginger lowers blood sugar. In one study, the anti-diabetic activity of ginger has been shown to be associated with its pungent gingerol principles. In this study, the extract of Zingiber officinale, Roscoe enhanced glucose uptake in rat’s skeletal muscle cells. Gingerols from active ginger fractions promoted skeletal muscle cell glucose disposal that was associated with an increased expression and translocation of GLUT-4 glucose transporter to the plasma membrane of the cells (12). This translocation of the GLUT-4 can effectively clear the glucose from the serum. Influencing on the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism is another probable impact of ginger that reduces blood sugar. In another study, daily administration of 500 mg/kg of an aqueous ginger extract decreased blood glucose levels in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats (20). This study showed that ginger increases muscle and liver glycogen stores by enhancing the peripheral utilization of glucose in the diabetic rats and limits the gluconeogenesis in the liver and kidney similar to insulin (20). Rani et al. (2010) suggested that phenolic compounds of ginger, gingerols and shoagols, inhibit the key enzymes relevant to type 2 diabetes management, such as α-glucosidase and α-amylase (21). It was also reported that 6-gingerol enhances insulin-sensitive glucose uptake at adipocytes (22).

One of the strong points of the current study is the high percentage of patient’s adherence to the study protocol. However, this study had some limitations. First, the supplementation period was short. Second, frequent inclusion criteria hampered the disease finding process with many difficulties and no matching procedure was performed. Third, taking lipid-lowering medications was not controlled in the patients because it hardens the recruitment of the subjects.

Further investigations with a longer duration, variable doses of ginger in a dose dependent study protocol and also lipid-lowering medications control are needed to evaluate the effect of ginger supplementation on glycemic index as well as lipid profiles in type 2 diabetes.

All these evidences show that a medium dosage of the ginger, which is applicable by a simple dietary manipulation, could modify glycemic and lipid status in experimental animals as well as human subjects. This shows the importance of food factors and dietary changes in control of diabetes. These dietary approaches could be used as complementary therapy, yet, not alternative therapy.

Conclusions

In this study, oral ginger supplementation decreased the levels of FBS, HbA1C, and LDL/HDL ratio in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus with no effect on other lipid profiles.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the vice-chancellor of research grant (grant number: 28653) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The authors sincerely appreciate Ziaeian hospital for recruiting the patients and the participants, who made this study possible. The authors are also thankful for the funding provided by the department of cellular and molecular nutrition, school of nutritional sciences and dietetics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Conception and design: Ahmad Saedisomeolia, Motahareh Makhdoomi Arzati and Niyaz Mohammadzadeh Honarvar; analysis and interpretation of data: Ahmad Saedisomeolia and Motahareh Makhdoomi Arzati; drafting of the article: Motahareh Makhdoomi Arzati and Niyaz Mohammadzadeh Honarvar; critical revision of the manuscript: Ahmad Saedisomeolia, Niyaz Mohammadzadeh Honarvar, Siyamand Anvari, Mohammad Effatpanah, Raoofe Makhdoomi Arzati and Mahmoud Djalali; statistical analysis: Mir Saeed Yekaninejad. All the authors approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Funding/Support:This study was supported by a grant provided by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (grant number: 28653), Tehran, Iran.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Effatpanah, Email: m.effatpanah@gmail.com.

Mir Saeed Yekaninejad, Email: yekaninejad@yahoo.com.

Rezvan Hashemi, Email: rezvanhashemi@yahoo.com.

Mahmoud Djalali, Email: mjalali87@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Kayarohanam S. Current Trends of Plants Having Antidiabetic Activity: A Review. J Bioanalysis Biomed. 2015;07(02) doi: 10.4172/1948-593x.1000124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguiree F. IDF diabetes atlas. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteghamati A, Gouya MM, Abbasi M, Delavari A, Alikhani S, Alaedini F, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in the adult population of Iran: National Survey of Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Diseases of Iran. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(1):96–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler MJ. Microvascular and Macrovascular Complications of Diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2008;26(2):77–82. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.26.2.77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue WS, Lau KK, Siu CW, Wang M, Yan GH, Yiu KH, et al. Impact of glycemic control on circulating endothelial progenitor cells and arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:113. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suba V, Murugesan T, Arunachalam G, Mandal SC, Saha BP. Anti-diabetic potential of Barleria lupulina extract in rats. Phytomedicine. 2004;11(2-3):202–5. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasani-Ranjbar S, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of Iranian medicinal plants useful in diabetes mellitus. Arch Med Sci. 2008;4(3):285–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khandouzi N, Shidfar F, Rajab A, Rahideh T, Hosseini P, Mir Taheri M. The effects of ginger on fasting blood sugar, hemoglobin a1c, apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein a-I and malondialdehyde in type 2 diabetic patients. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14(1):131–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nammi S, Sreemantula S, Roufogalis BD. Protective effects of ethanolic extract of Zingiber officinale rhizome on the development of metabolic syndrome in high-fat diet-fed rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;104(5):366–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shukla Y, Singh M. Cancer preventive properties of ginger: a brief review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45(5):683–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng XL, Liu Q, Peng YB, Qi LW, Li P. Steamed ginger (Zingiber officinale): Changed chemical profile and increased anticancer potential. Food Chem. 2011;129(4):1785–92. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Tran VH, Duke CC, Roufogalis BD. Gingerols of Zingiber officinale enhance glucose uptake by increasing cell surface GLUT4 in cultured L6 myotubes. Planta Med. 2012;78(14):1549–55. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahluji S, Attari VE, Mobasseri M, Payahoo L, Ostadrahimi A, Golzari SE. Effects of ginger (Zingiber officinale) on plasma glucose level, HbA1c and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2013;64(6):682–6. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2013.775223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bordia A, Verma SK, Srivastava KC. Effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) and fenugreek (Trigonella foenumgraecum L.) on blood lipids, blood sugar and platelet aggregation in patients with coronary artery disease. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Essential Fatty Acids. 1997;56(5):379–84. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(97)90587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oludoyin AP, Adegoke SR. Efficacy of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) extracts in lowering blood glucose in normal and high fat diet-induced diabetic rats. Am J Food Nutr. 2014;2(4):55–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazeem MI, Akanji MA, Yakubu MT, Ashafa AOT. Protective effect of free and bound polyphenol extracts from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) on the hepatic antioxidant and some carbohydrate metabolizing enzymes of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Evid Base Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/935486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozougwu JC, Eyo JE. Evaluation of the activity of Zingiber officinale (ginger) aqueous extracts on alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Pharmacologyonline. 2011;1:258–69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Amin ZM, Thomson M, Al-Qattan KK, Peltonen-Shalaby R, Ali M. Anti-diabetic and hypolipidaemic properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(4):660–6. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arablou T, Aryaeian N, Valizadeh M, Sharifi F, Hosseini A, Djalali M. The effect of ginger consumption on glycemic status, lipid profile and some inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2014;65(4):515–20. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2014.880671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdulrazaq NB, Cho MM, Win NN, Zaman R, Rahman MT. Beneficial effects of ginger (Zingiber officinale) on carbohydrate metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(7):1194–201. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511006635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rani MP, Padmakumari KP, Sankarikutty B, Cherian OL, Nisha VM, Raghu KG. Inhibitory potential of ginger extracts against enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes, inflammation and induced oxidative stress. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62(2):106–10. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2010.515565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekiya K, Ohtani A, Kusano S. Enhancement of insulin sensitivity in adipocytes by ginger. Biofactors. 2004;22(1-4):153–6. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520220130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]