Abstract

Natural resources, biotic and abiotic, are fundamental from both the ecological and socio-economic point of view, being at the basis of life-support. However, since the demand for finite resources continues to increase, the sustainability of current production and consumption patterns is questioned both in developed and developing countries. A transition towards an economy based on biotic renewable resources (bio-economy) is considered necessary in order to support a steady provision of resources, representing an alternative to an economy based on fossil and abiotic resources. However, to ensure a sustainable use of biotic resources, there is the need of properly accounting for their use along supply chains as well as defining a robust and comprehensive impact assessment model. Since so far naturally occurring biotic resources have gained little attention in impact assessment methods, such as life cycle assessment, the aim of this study is to enable the inclusion of biotic resources in the assessment of products and supply chains. This paper puts forward a framework for biotic resources assessment, including: i) the definition of system boundaries between ecosphere and technosphere, namely between naturally occurring and man-made biotic resources; ii) a list of naturally occurring biotic resources which have a commercial value, as basis for building life cycle inventories (NOBR, e.g. wild animals, plants etc); iii) an impact pathway to identify potential impacts on both resource provision and ecosystem quality; iv) a renewability-based indicator (NOBRri) for the impact assessment of naturally occurring biotic resources, including a list of associated characterization factors. The study, building on a solid review of literature and of available statistical data, highlights and discusses the critical aspects and paradoxes related to biotic resource inclusion in LCA: from the system boundaries definition up to the resource characterization.

Keywords: Biotic resources, Impact assessment, Indicators, Renewability, Carrying capacity, Life cycle assessment

Highlights

-

•

Illustration of the impact pathways for biotic resources in LCIA.

-

•

List of marketable naturally occurring biotic resources (NOBR) for life cycle inventories.

-

•

Naturally occurring biotic resource renewability indicator (NOBRri) proposed for ranking resources in LCIA.

-

•

Identification of key aspects for a comprehensive characterization of biotic resources.

1. Introduction

The secure access to natural resources, both abiotic and biotic, provided by the Earth, i.e. metals, mineral, wood, water, air, and soil, is the basis for human life and socio-economic well-being. In fact, natural resources have direct or indirect functions for humans both representing a building block in the supply chains as material inputs, thus enhancing the economic growth, and being fundamental for the provision of services and functions by ecosystems, for instance climate regulation.

Historically, economies in developed countries have been characterized by a high level of both abiotic and biotic natural resources consumption, including fossil resources used for energy, transport, materials, and chemicals production (Mancini et al., 2015). However, in a globalized world where population is expected to reach 9 billion people by 2050 and demand and competition for finite resources continue to increase, the sustainability of the existing production and consumption patterns is raising concerns both for environmental implications and in terms of security of resource supply (UNDESA, 2015). On such a background, economies worldwide need to radically revise the current approach to production and consumption, improving the efficiency in resource use for both abiotic and biotic resources, in order to meet challenging objectives such those included in the Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2016). As a response to the conventional fossil-based economic model, the transition towards a bio-based economy (bio-economy) has been put forward. Bio-economy refers to the economic activities relating to the production, use, and development of biological products and processes (OECD, 2009), and it is specified as the sustainable production and efficient use of renewable biological resources proceeding from agriculture, forestry, fishery etc., and their subsequent conversion into value added products, such as food, feed, industrial materials and energy (EC, 2012). The concept has been already translated in action plans in different context. For example, some EU policies –such as the Biomass Action Plan (EC, 2005) and the Renewable Energy and Fuel Quality Directives (EU, 2009a, EU, 2009b)– already promoted the bio-economy (EC, 2010, EC, 2012).

The intrinsic renewability of biotic resources make them, theoretically, more available compared to finite resources. However, their supply could be considered critical as well, if the carrying capacity of the ecosystems responsible for their provision is overcome, namely when resources are extracted at a rate higher than their regeneration capability. In fact, renewable resources do not continue to grow indefinitely and they can be depleted beyond the point of renewability, for instance, when commercially valuable species are harvested to extinction. The assessment of the carrying capacity is a key element of environmental sustainability, crucially needed for sustainability assessment and for integrated assessment methodologies as life cycle assessment (LCA) (Sala et al., 2013a, Sala et al., 2013b).

Notwithstanding it is often claimed that renewable biotic resources or bio-based products (i.e. products wholly or partly derived from biomass) represent the appropriate solution for a sustainable post-fossil carbon society, it is clear that “renewable” and “bio-based” are not necessarily synonymous with “sustainable”. This may seem a paradox, but biotic resources could be as critical as fossils or abiotic ones, if the processes underpinning their renewability are affected beyond the ecosystem's carrying capacity or beyond the sustainability of the underpinning bio-geological cycles. For example, agriculture products could not be indefinitely produced without certain quality of soil, pollination service, an adequate amount of available water, etc. Moreover, bio-based products and energy may anyway imply a significant amount of embodied fossil-based energy (Arvidsson et al., 2012) for their production, as well as may be associated with direct and indirect land-use impacts. The nexus between the use of biotic and abiotic resources for competing uses (e.g. food, energy, materials) (Karabulut et al., 2017) and the interplay between ecosystems and resources is still not fully explored. For example, several studies have already highlighted that large-scale cultivation of biomass for biofuel may affect global food security and natural ecosystem functioning (e.g. Smith et al., 2010). From the material point of view, the criticality of biotic resources is increasingly recognized (e.g. from 2014, three biotic raw materials have been included in the list of European critical raw materials-rubber, pulpwood and sawn softwood- EC, 2014).

In this context, holistic methodologies such as LCA (ISO, 2006) are necessary to ensure that different drivers of environmental impacts are simultaneously considered and burden shifting avoided. However, biotic resources have been barely considered within LCA and specific improvements are needed to better capture impacts related to biotic resource extraction and use. At the moment, in an LCA study, if a product is based on natural occurring biotic resources, the resources themselves are not accounted for the majority of the cases since elementary flows are mainly missing and no characterization of the resources is performed.

Firstly, the transition towards bio-economy requires more specificity in resource accounting. Statistics usually report data on biomass from harmonized statistical sources such as agricultural crop, forestry and fishery databases; however, at a high level of aggregation (e.g. wood) (Eurostat, 2016). Besides, a comprehensive and robust model of impact assessment needs to be developed for natural biotic resources, to ensure the sustainable use thereof. In the last decades, several methodologies and indicators, including life cycle oriented approaches for biotic resource depletion, have been developed with different purposes. However, typical concerns for biotic resources, such as the large global capture of fish from wild fisheries and the overharvesting of natural wood resources, are not generally accounted in such methodologies. Moreover, within supply chain management, a robust characterization of biotic resources and a reliable set of indicators are actually missing in a framework of impact assessment. Therefore, additional investigations are necessary in order to cover the research gaps, by integrating biotic resources as an impact category within the Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA).

This study is a methodological paper aiming at unveiling the challenges in biotic resources' accounting and the limitations associated with the characterization step towards the inclusion of biotic resources within LCA. A model for the assessment of biotic resources is proposed, encompassing: i) a definition of system boundaries between ecosphere and technosphere, namely between naturally occurring and man-made resources; ii) a list of biotic resources focusing on commercially valuable resources coming from the wild (i.e. naturally occurring biotic resources - NOBR, e.g. wild animals, plants, etc.), as basis for building life cycle inventories; iii) an impact pathway and an impact assessment model and associated characterization factors (CFs) for ranking resources based on one key element of their sustainability: the renewability potential. The study, building on a solid review of literature and of available statistical data, highlights and discusses the critical aspects and paradoxes related to biotic resource inclusion in LCA: from the system boundaries definition up to the resource characterization.

The paper is organized as follows: section 2 focuses on the state of the art of the accounting and characterization of natural biotic resources in LCA; section 3 presents an overview of the methodological steps adopted in this study towards the inclusion of biotic resources in LCA, encompassing the system boundaries, the impact pathway, the biotic resources to be considered in the inventory and their characterization; in section 4 we present the results of the extensive literature review, discussing the role of natural biotic resources into the current LCA framework and the proposed indicators to characterize natural biotic resources; sections 4 presents the results and the discussion on the key aspects to be taken into considerations for improving the accounting and the impact assessment of natural biotic resources, proposing a new indicator for the characterization; finally, section 5 encloses the conclusions and suggestions for further research.

2. State of the art of the accounting and characterization of natural biotic resources in LCA

It is a shared issue that the extensive harvesting of biotic resources from the ecosphere, such as fish and wood, at a level above their respective renewal rates poses a pressure on their future availability (Klinglmair et al., 2014, FAO, 2016c, FAO, 2016d). However, a robust characterization and a reliable set of indicators are still missing in a framework of life cycle based impact assessment, and further research is necessary. In the last decades, several methodologies and indicators have been developed in order to take into account the environmental, social and economic relevance of natural biotic resources in a context of resource depletion:

-

•

Resource accounting-based methods, e.g. Material Flow Analysis (MFA) (Hinterberger et al., 2003), are mass-based accounting approaches seeking to quantify environmental pressures from resource consumption. They include exchanges of biotic material, such as biomass from agriculture, forestry and fishery, quantifying their use in terms of mass, without characterizing the intrinsic properties of each material.

-

•Resource characterization-based methods, instead, relate resources to physical, chemical or biological factors that describe their relevant properties. Characterization is an essential component of many impact assessment frameworks. Among these approaches:

-

◆Footprinting, e.g. ecological footprint (Global Footprint Network, 2016), developed to measure human pressures on bio-capacity of the Earth. Specifically, ecological footprint accounts for the flows of energy and matter, including biotic resources, to and from any economic system and converts them into the corresponding proportion of the Earth's bio-productive land or water areas required to supply resources to a particular human activity.

-

◆Impact assessment-based methods, founded on the LCA, where biotic resources and their renewal rates have so far received relatively little regard (Klinglmair et al., 2014).

-

◆

Despite many efforts, current LCA frameworks miss a specific focus on natural biotic resources. In fact, LCA inventories lack of a complete list of elementary flows for natural biotic resources (Table 1) as well as models for a comprehensive characterization. Hence, there is the need to cover this conceptual gap, overcoming the current limited coverage of biotic resources, especially with regards to some categories like top-soil, forest biomass and fish stocks which have relevance for the global economies (EC-JRC, 2016).

Table 1.

List of natural biotic resources and their units currently included in one LCA inventory database, i.e. Ecoinvent v.3.3 (2016).

| Resource name in Ecoinvent 3.3 | unit |

|---|---|

| Animal matter | kg |

| Biomass | kg |

| Biomass, feedstock | MJ |

| Carbon, organic, in soil or biomass stock | kg |

| Fish, unspecified, in sea | kg |

| Peat | kg |

| Wood (16.9 MJ/kg) | kg |

| Wood and wood waste, 20.9 MJ per kg, oven dry basis | kg |

| Wood and wood waste, 9.5 MJ per kg | kg |

| Wood, dry matter | kg |

| Wood, feedstock | kg |

| Wood, hard, NE-NC, standing | m3 |

| Wood, hard, standing | m3 |

| Wood, primary forest, standing | m3 |

| Wood, soft, INW, standing | m3 |

| Wood, soft, NE-NC, standing | m3 |

| Wood, soft, standing | m3 |

| Wood, soft, US PNW, standing/m3 | m3 |

| Wood, soft, US SE, standing/m3 | m3 |

| Wood, unspecified, standing/kg | kg |

| Wood, unspecified, standing/m3 | m3 |

NE-NC: Northeast North Central; INW: Inland West; US PNW: United States Pacific Northwest; US SE: United States Southeast.

The identification of the elementary flows needs a considerable effort in order to establish a harmonized and unified reference terminology within the inventories. Then, an inventory analysis based on mass accounting of the elementary flows referred to a product or service would not be enough to perform an impact assessment. Some specific aspects, like the ecological properties together with the geographical localization of the extraction of the resources, are fundamental in view of a complete analysis of natural resources. To date, there is no consensus on how to proper address the area of protection “Natural Resources” in LCA (Dewulf et al., 2015). In the case of biotic resources, beyond no consensus on how to derive impact factors for assessing their depletion (Klinglmair et al., 2014), there are very few impact assessment models addressing the issue. This is principally due to the complexity of assessing the impacts, the need of further clarifying the boundaries between ecosphere and technosphere as well as the fact that characterizing a mass-based accounting is challenging in terms of suitable metrics for assessing impacts. Currently, a model for the characterization of biotic resources is not available within the International reference Life Cycle Data system (ILCD) recommendation for LCIA by the EC-JRC (2011). Although impacts on habitats of biotic resources are assessed in the Area of Protection “Ecosystem Quality”, damages to biotic resources related to depletion (such as overharvesting, overfishing and overhunting) remain not accounted within the ILCD recommended framework.

To date, the attempts made over time to include biotic resources in a life cycle framework use different models and indicators (Table 2).

Table 2.

Natural biotic resource coverage according to the methods existing within current literature.

| Model | Indicator | Unit | Natural Biotic Resources | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exergy | Cumulative Energy Extracted from the Natural Environment | MJex/unit | wood | Dewulf et al., 2007, Alvarenga et al., 2013, Taelman et al., 2014 |

| Emergy | Solar Energy Factor (SEF) | MJse/unit | wood | Rugani et al. (2011) |

| EPS 2000 | Environmental Load Units (ELU) | ELU/kg | wood, fish & meat | Steen (1999) |

| BRD-fish (Biotic Resource Depletion) | 1/maximum sustainable yield (MSY) or 1/current fish catches (Ct) [to be applied in case of overexploitation] |

yr/t | Fish | Langlois et al. (2014) |

| LPY-fish (Lost Potential Yield) | Lost Potential Yields (LPY) | dimensionless | Fish | Emanuelsson et al. (2014) |

| BIRD | Biotic Resource Availability (BRA) | dimensionless | Terrestrial biotic materials | Bach et al. (2017) |

The EPS 2000 (Steen, 1999) is a damage oriented model, with the highest coverage of biotic resources, including fish, meat and wood. In the EPS system, Willingness to Pay (WTP) to avoid damages to natural resources' availability is chosen as indicator for characterizing biotic resources in monetary terms.

Other models are based on thermodynamic features of resources. For example, exergy-based LCA models, such as Dewulf et al., 2007, Alvarenga et al., 2013, Taelman et al., 2014, aim at assessing the quality of resources depending on the amount of useful energy needed for producing them and that could be obtained from them. Besides, emergy-based LCA model (Rugani et al., 2011) aims at measuring the Solar Energy Demand (SED) associated with the extraction of resources, including both naturally occurring and man-made biotic ones.

Recent attempts seeking to develop a characterization model to assess human-related impacts on natural biotic resources within the LCIA framework come from the studies of Langlois et al. (2014), Emanuelsson et al. (2014) and Bach et al. (2017).

Langlois et al. (2014) proposed quantitative approaches to address overfishing at the midpoint level. In fact, the authors reviewed the use of the sea in LCA and developed a methodological framework, then implemented by Helias et al. (2014), to assess impacts of fish depletion at both species and ecosystem levels. The model of Langlois et al. (2014) is based on the concept of biotic resource depletion for fish, which aims to characterize the current biomass uptake related to either the Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY, based on fisheries science) or the current fish catches in case of overexploitation. This model, which provides characterization factors for 127 fish species, allows evaluating the environmental pressures on fisheries in a context where one third of global fish stocks is already overexploited. The study is the first attempt to assess impacts on the use of biotic resources taking into account ecological aspects such as the resource recovery capacity.

In parallel with the study of Langlois et al., 2014, Emanuelsson et al., 2014 focused on the concept of Lost Potential Yield (LPY) for fish, proposing new characterization factors for 31 European fish species. The model aims at measuring and characterizing the current overexploitation of natural fish stocks, suggesting a midpoint indicator that allows identifying the impacts on the reduction of future fish supply.

Bach et al. (2017) propose the BIRD approach, inspired by the abiotic depletion potential (Van Oers et al., 2002). The BIRD model focuses on terrestrial biotic resources, as the majority of the LCA models above-mentioned, and it measures the availability of biotic resources by using the BRA indicator (defined as availability to use ratio). In their proposal, the authors include considerations on the replenishment rate and the identification of a reference species. Differently from other models, in this approach, several aspects beyond the ecological constraints are taken into account (e.g. socio-economic aspects).

All in all, the applicability of these approaches is limited in the context of current LCA since elementary flows and life cycle inventory for terrestrial resources and fish are still missing.

For what concern wood, several of the above-mentioned models consider this material, which is included in the LCIA framework as an energy resource. Wood is one of the most versatile raw materials, employed in a variety of industrial processes and domestic uses (Schweinle, 2007). It is generally taken into account as simple “wood”, or just making a distinction between “hardwood” (i.e. wood stemming from broadleaves) and “softwood” (i.e. wood coming from coniferous), without addressing the species, the distribution around the globe, the original habitat (natural forests versus human-made plantations) or species vulnerability. When coming to the impact assessment, this lack of specificity in the accounting could generate an over- or under-estimation of the impacts which biotic resources are subject to, due to ecological features that may results in population dynamics of plants being more or less sensitive to human interventions. For instance, the impacts on biotic resources due to the extraction of wood from widespread oaks is likely to be different from the impact which may affect the extraction of wood from a threatened and endemic plant species growing in specific locations. The focus on the species, their distribution and their ecological status is fundamental in order to effectively assess the effects of extracting biotic resources and characterize them.

Regarding soil, the threats to soil as a biotic resource may be the result of a physical removal (e.g. erosion or physical loss due to building construction or other human interventions) or a detriment in its quality, meaning that the resource is not available anymore for a specific life-support function (e.g. due to salinization, compactation, etc). However, the variety of soils and their properties, their widespread distribution around the globe and the heterogeneity of pressure they undergo suggest the need of a comprehensive impact assessment scheme, which has not been standardized so far. In a recent review (Vidal Legaz et al., 2017), soil quality models for impact assessment were analyzed, highlighting that current models for soil related impacts are not yet able to comprehensively cover both the areas of protection “Ecosystem Quality” and “Natural Resources”. An additional research by Curran et al. (2010), in which the authors reviewed the use of indicators and approaches to model biodiversity loss due to land/soil use within the LCA framework, outlined serious conceptual and methodological gaps to be covered in the way the soil related impacts are modeled for addressing biodiversity concerns.

Overall, human driven impacts on marine and most terrestrial biotic resources still remain unaccounted within current LCA framework since these models are not yet operational and no official guidelines exist for biotic impact assessment (Emanuelsson et al., 2014, Woods et al., 2016).

3. Methodology

Based on the state of the art, it is clear that several aspects are still missing for a complete inclusion of naturally occurring biotic resource in LCA. Hence, the focus of the study is the improvement of the LCA framework towards a better inclusion and assessment of biotic resources and their availability. For each methodological step, our study is grounded on a thorough review of existing literature and available statistical data. Information and data were collected and integrated into a larger database in order to classify and characterize naturally occurring biotic resources (NOBR).

The methodology of this study involved several steps:

-

1.

Illustration of the impact pathway (cause-effect chain) that links biotic resources with impact on the areas of protection “Natural Resources” and “Ecosystem Quality”;

-

2.

Definition of the system boundaries, namely the criteria to identify which are the biotic resources that should be addressed by the resource accounting and impact modeling;

-

3.

Collection of available data on naturally occurring biotic resources for providing a list of biotic resources. This list could be used for building elementary flows to be used in future life cycle inventories.

-

4.

Proposal of an indicator based on renewability to characterize and rank biotic resources, based on an extensive review of literature in the ecology domain.

3.1. The impact pathway associated to biotic resources

Life cycle impact assessment models are built to characterize the impacts on the environment due to emissions or resource uses. Hence, the first step is the illustration of the impact pathway, in terms of the potential cause-effect chain along which human interventions may generate impacts. In principle, the overexploitation of biotic resources may be associated with two different areas of protection (Fig. 1). On one hand, using resources beyond their carrying capacity may be detrimental for the future supply of resources for human needs, leading to an impact on the area of protection “Natural Resources”. On the other hand, the overexploitation may imply consequences on the area of protection “Ecosystem Quality”, namely when the use is associated with a direct biodiversity loss (the extinction of those species which are used as a biotic resource, e.g. a fish species used as food) or an indirect biodiversity loss (the reduction of biotic resources which leads to an impact on e.g. a trophic chain). Several threats to biodiversity have been associated to the use of naturally occurring resources (e.g. in Lenzen et al., 2012, focusing on impacts due to trade). In this paper, biotic resources are addressed limiting the focus on their role in supporting human activities, i.e. as input material in the socio-economic system, and not for their contribution to ecosystem quality and functioning (which would fall into the area of protection “Ecosystem Quality”).

Fig. 1.

Cause-effect chain outlining the scope of the paper about the accounting of biotic resources and the characterization of their availability. PDF = Potentially Disappeared Fraction of species.

3.2. The definition of the biotic resources to be assessed

In LCA, the impacts associated to natural resources produced by human interventions are usually captured assessing the environmental profile of the processes underpinning their production (e.g. cultivation), whereas the impacts linked with naturally occurring biotic ones are usually barely covered in life cycle inventories. Although the processes for their extraction from biosphere are accounted (e.g. emission due to harvesting of woods), the impacts of their extraction are neither characterized in the area of protection “Natural Resources” nor in the “Ecosystem Quality”.

According to the approach proposed by Alvarenga et al. (2013), we then provided the clarification of the system boundary. We thus identified and set the boundary between ecosphere and technosphere when coming to define what natural biotic resources are, i.e. when dealing with biotic resources extracted from natural environment and used by humans (“A - Naturally occurring biotic resources” in Fig. 2) versus biotic resources produced by human interventions such as crops from agriculture (B). The B box in the figure refers to the fact that crops, which are the result of human interventions in the technosphere, require natural inputs from ecosphere and the boundary is often difficult to be defined in agricultural systems compared to industrial systems.

Fig. 2.

System boundary for natural biotic resources, that are distinct in those naturally occurring (A) and those resulting from human interventions (B). Adapted from the approach developed by Alvarenga et al. (2013).

In the present study, we focus on naturally occurring biotic resources, i.e. (A), those commercially valuable resources proceeding from biological sources (i.e. plants, animals and other organisms) that are caught or harvested from ecosphere as input material for human purposes like wild feed and food, wood and other products from natural forests, etc. Natural organic topsoil has been included into our analysis, since it is one of the critical underpinning renewable resource (in the ecosphere) that sustain the production of crops (in the technosphere).

3.3. Towards building an inventory of natural occurring biotic resources (NOBR)

The first step -for including naturally occurring biotic resources in the LCA framework- is the identification of which biotic resources should be accounted for. In order to build a list of the resources commercially valuable, proceeding from biological sources (i.e. plants, animals and other organisms) that are caught or harvested from ecosphere as input material for human purposes, we consulted specific reports and databases, such as, just to name a few, FAO databases for forestry and fishery statistics (FAO, 2016a, FAO, 2016b), Artemis-face database from the European Federation of Hunters for game hunting information (FACE, 2016) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list of threatened species (IUCN, 2016). Thus, by collecting and combining data from different sources, we identified and integrated a list of NOBR in a database, excluding those proceeding from agriculture, aquaculture and livestock, since they depend on human interventions. This list could be the basis for a list of elementary flows to be used in life cycle inventories. Moreover, we sought for data on the availability, use, and consumption of biotic resources to understand how these are distributed and shared within the markets at different scales, both local and global. The data on availability and consumption have been collected to demonstrate that the resource is used somewhere in the economy, so is a resource used by humans. This step is fundamental to identify the biotic resources currently used and, hence, for which of them data may be available, in future, for populating life cycle inventories.

3.4. Life cycle impact assessment indicator for biotic resources based on renewability

As mentioned earlier, in this study we aim at identifying an indicator to be used for the impact assessment of naturally occurring biotic resources. The indicator should increase comprehensiveness and ecological relevance in assessing biotic resources, beyond the state of the art (section 2). Since the scope is to rank the resources based on the likelihood of a reduction in their availability, we propose an indicator for biotic resources based on the renewability rate. Renewability rate of natural biotic resources is a key ecological concept that could be adopted as a basis to identify the ecological and environmental features of the analyzed biotic resources, thus to characterize them. This indicator could be considered a midpoint indicator that could be further complemented with indicators of e.g. carrying capacity, availability-to-use ratios or species vulnerability, towards endpoint modeling either in the related area of protection “Natural Resources” or “Ecosystem Quality”.

Renewability is one of the basis for assessing the potential reduction in the future availability of biotic resources, assuming that resources with longer renewability rate may be more exposed to a wide range of pressures ultimately undermining their provision. Therefore, we referred to the renewability and regeneration time, which represent key elements assessed in ecology, specifically, in population dynamics, as a potential proxy indicator for the capability of a species to grow and regenerate over time. The literature on population dynamics is vast; however, systematized information on renewability and regeneration time for species with a commercial value was not available (to the knowledge of the authors). On this basis, we conducted a systematic review of the literature, initially searching the ISI Web of Science database, which provides access to peer-reviewed studies, in order to have a preliminary understand about the spread and the actuality of this issue. The criteria for this search are reported in the supplementary material (Table S1), along with all the literature consulted.

Conforming to the increasingly widespread cross-interest in the concept of renewability and resilience (Curtin and Parker, 2014), we set up a “renewability-based” database. Through a detailed search of all types of published literature and using a snowball search, we identified relevant references to point out potential reliable indicators for biotic resources. To carry out our refined search, we started identifying key terminology related to renewability and regeneration, such as: renewal time, regeneration period, growth rates, recovery time, restoration time, and similar others. Those terms were selected according to the terminology predominantly used in the ecological domain. As an example, we combined in a concatenated string of words either the common or the scientific name of biotic resources (e.g. “sturgeon*” or “Acipenser oxyrinchus“), or even categories of them, like “marine fish” and key words such as those presented above, using the Boolean command AND. We queried online bibliographic databases such as Google Scholar, SCOPUS, Web of Science and the libraries of specific journals like Global Ecology and Conservation. To improve the results, we refined the investigation focusing on a reduced sample of species, namely the most valuable species from the commercial point of view (i.e. the most commercialized globally or locally) and the most representative from the conservation point of view, which means the most threatened by the risk of extinction. Therefore, we searched for studies focusing on single species. In the case of both terrestrial and marine fauna, we were interested in the features of the population dynamics. Thus, we adopted terms of search like “population doubling time” (or simply “doubling time”), “doubled population” or “population life cycle”; while for plants, we used silviculture terms such as “rotation period”, “reproduction time” or “regeneration period”, in combination with the common or specific name.

The outputs included different types of scientific literature, predominantly reports on conservation and management of species and ecological studies. However, the overwhelming majority of the selected papers proceeded from grey literature and reports from international organizations. The publication years of the whole research ranged from the 1970's to date.

Finally, we created a database (see Table S2 and Table S3) to collect the list of naturally occurring biotic resources and their related ecological characteristics in order to analyze and discuss the pattern of distribution and renewability of biotic resources and eventually estimate the characterization factor to be used within the LCIA phase. In particular, the recorded information include living organism category, commercial group, common species name, scientific species name, family name, distribution (local or global) and habitat, the vulnerability score according to IUCN criteria where available, renewability indicator type and its quantification.

4. Results and discussion for the inclusion of natural occurring biotic resources in LCA

According to the steps illustrated in section 3, our proposal for the inclusion of naturally occurring biotic resources in the LCA framework and their characterization builds on the following results:

-

•

the identification of natural occurring biotic resources and the population of a database of commercial valuable naturally occurring biotic resources, reporting their renewability rates.

-

•

the proposal of a renewability based indicator for biotic resource characterization, built from a review of available information on resources renewability and regeneration time.

For all the sections, data are available as supplementary material to this paper.

4.1. Natural occurring biotic resources with a commercial value: classification of the resources and data availability

Based on the review of literature and available statistical data, naturally occurring biotic resources have been classified in the following major categories, according to their taxonomic level: aquatic and terrestrial vertebrates, aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates, terrestrial plants, aquatic plants and algae, fungi, aquatic and terrestrial animal products, terrestrial plant products (Table S3, including figures on availability, use, consumptions and references). As mentioned above, we included soil as well.

According to our analysis, naturally occurring biotic resources are most commonly used as material input in a broad array of industrial sectors, ranging from food to chemical and pharmaceutical sectors, up to production of e.g. furniture. Together with their derived products, they are generally used as commercial goods marketed at global level, in terms of food and feeding, as source of energy, in the cosmetics, as medicines and for the production of other accessories in different branches of the industrial sector (e.g. natural pearls, natural latex). Several natural biotic resources, such as wild plants, are used in local communities, especially in the developing countries, as dyes, poisons, shelter, fibers and in religious and cultural ceremonies (Heywood, 1999).

It is worth noting that, even though naturally occurring biotic resources are spread around the world and the overwhelming majority of them are commercially used on a global scale, so far a complete list was missing within the available literature. An important attempt was made by Schulp et al. (2014), who synthesized and mapped the ecosystem service called “wild food”, quantifying the supply of terrestrial edible species (i.e. game, mushrooms and vascular plants) across Europe. Gathering a broad list of around 150 species based primarily on their commercial use allows us to start connecting natural biotic resources to elementary flows within the LCA framework.

The literature search showed that, recently, the issue related to the stock of natural biotic capital and its renewability has become central in the ongoing discourse about resource depletion within the scientific circle (Fig. S1).

In spite of the recognized role of naturally occurring biotic resources in human daily life, accurate data on their availability and renewability rate were difficult to gather in the scientific literature. On one hand, this may occurr because most countries, especially the developing ones, have less or no official supervision on the volume of biotic material harvested from the wild and quantities collected are scarcely inventoried. On the other hand, it is often difficult to distinguish between wild and cultivated resources, especially in the case of wild plants, as such primarily wild-collected products are often sold as cultivated (Kuipers, 1997). Some information exists on a reduced number of natural biotic products; however, the available data are extremely variable in coverage and reliability. In fact, the majority of retrieved data were scattered among reports and databases proceeding from different sources, disciplines and institutions, reporting information limited to some specific locations.

The availability of data on biotic resources is generally linked to: i) their use as material input in the industrial sectors of developed countries; ii) their consumption as food; or, iii) to the vulnerable state of their populations (IUCN, 2016). In most cases, statistics are provided by national authorities. However, figures are often incomplete due to the considerable variation in the consumption patterns among continents, countries and communities. On the other hand, this type of information is predominantly related to biotic resources linked to human interventions such as those products of agriculture, aquaculture, livestock or to the re-introduction following conservation action plans.

We found predominantly data on resource availability related to few groups of organisms, especially the most commercialized animals such as targeted marine fish species (see FAO, 2016a) and game mammals and birds, since they are likely the most easily captured and consumed natural products all over the globe. Moreover, the overexploitation and the potential subsequent collapse of marine and freshwater fish populations is a well-known issue that may affect populations up to not being available in the future (Hutchings, 2000). Results of the review and data gathering are reported in the supplementary material (Table S3).

Wild plants, particularly those used in rural communities, and wild mushrooms tend to receive less recognition. Data on their availability are general scarce and rarely published in literature since their collection and consumption are at subsistence level and no legislative and policy support for wild harvesting procedures is arranged. Bais et al. (2015) started covering the gap in the substantial lack of knowledge related to the amount and use of hardwood in a reduced number of world regions. However, overall there are no precise global figures available on the total volume of wild-collected natural resources and on their spatio-temporal patterns in the global market. Furthermore, understanding the magnitude of illegal logging and hunting, which represent a serious problem for biotic resources all over the world, is not immediate. Although many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other institutions such as UNEP have so far collected information about these activities (UNEP, 2017), comprehensive country-specific statistics on illegal forest logging and wildlife hunting are difficult to quantify and use in an LCA perspective due to their fragmentary nature. Generally, indirect methods are adopted for these estimations, mainly focused on illegal international trade for commercial use (Kleinschmit et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the loss of biotic resources is measured in terms of percentage of logging activity (as reported by Kleinschmit et al., 2016), or in million cubic metres roundwood equivalent (RWE) volume (according to WWF, 2007) or, referring to illegal trade in wildlife, in terms of dollars annually (according to Nellemann et al., 2012). These values are not equivalent, thus making difficult to combine and compare the available data. Moreover, in the case of monetary measurement, they are not properly representative of biotic resource depletion since they do not account for either the availability or the renewability rate of resources.

4.2. A renewability-based indicator for characterizing biotic resources in LCIA

The current available approaches to biotic resource characterization are relatively limited for what concern the ecological relevance of the approach. Hence, in order to identify suitable characterization factors for natural biotic resources to be employed within the LCIA framework, a better understanding of the effects of human interventions on the availability of biotic resources is needed. The indicator that we are proposing is an attempt to fill the ecological gap focusing on renewability of natural resources. Two steps were followed to define the indicator:

-

•

a literature review on renewability rate and regeneration time

-

•

the calculation of characterization factors based on renewability.

4.2.1. Renewability rate and regeneration time of biotic resources

Information related to renewability or recovery rate (see Table S3) was found to be species specific, and in many cases population specific, depending on the magnitude of the environmental or human stressors they are subject to. This aspect may represent a limitation when coming to gather data, since a huge amount of data (e.g. population growth, spatial distribution of the species, etc.) should be taken for describing the depletion of a biotic resource's stock, thus restraining the possibility of elaborating a model for characterizing natural biotic resources.

The ecological data on fish species were represented by the renewability rate of species, called “resilience” within the Fishbase dataset (Fishbase, 2016), a global information system about fishes which gathers information provided by different professionals such as research scientists, fisheries managers and zoologists. The indicator used is the “population doubling time” (i.e. the amount of time it takes for a population to double in size or value at a constant growth rate), an indicative measure of renewability that can make possible the comparison with other animal species in order to elaborate physical indicators and models for the impact assessment within the LCIA framework. Data on the renewability rate within the population dynamics domain are available for several species, but just in particular context and just in few cases it is possible to generalize the data to a global or national level as it is necessary in LCA, being the studies very context-dependent. Furthermore, although changes in population size following medium-long term pressures have been measured for several species in terms of percentage of increase or decrease over time (e.g. elephants, see Ogutu et al., 2014, Okello et al., 2008), population- or species-specific indicators based on renewal time and their estimations were not available as a systematic list to be used for our purposes.

Given the differences in population dynamics and modeling thereof, there is not an equivalent renewability measure or indicator on species others than fish, thus making the comparison between species problematic. Among the indicators about species renewability, the most suitable in the view of falling into the LCIA scheme were the following: a) “biomass at maximum sustainable yield (MSY)” (OECD, 2017), mainly applied to fish stocks, which is considered as the largest yield (in tons) that can be caught from a specific fish stock over an indefinite period of time under constant environmental conditions; b) recovery of population size, to be considered as the time needed to a population to return to its pristine conditions following a decline.

MSY has been heavily criticized for both practical and theoretical reasons, namely: (i) a general lack of reliability of data to make a clear determination of the population size and growth rate; (ii) missing the fact that populations undergo natural fluctuations in abundance and would become severely depleted under a constant-catch strategy; (iii) the tendency to ignore the broad variety of aspects of population structure, such as age classes and their differential rates of growth, survival and reproduction (Townsend et al., 2008).

Data on renewability time of natural forests and other commercial plants from natural habitats were difficult to gather as well. In fact, it was complicated to distinguish between data proceeding from plantations or from natural forest management, especially in the case of tropical forests harvested for hardwood, fruit and latex. On this basis, we identified those species or categories of products that may come not only from natural forests, but also from cultivation (i.e. cork from the bark of the cork oak, etc.).

Generally, the rotation period (defined as the period between regeneration establishment and final cutting (SAP, 1994)) and natural regeneration or reproduction period (i.e. the time between the initial regeneration cutting and the successful reestablishment of a new age class by natural means, planting or direct seeding (SAP, 1994)) are reported. However, these parameters vary depending on altitude and soil fertility and, in forest management, regeneration time can be set depending on current market demand, thus generating a sort of human-dependency which overcomes the natural life cycle and recovery of resources.

Ideally, the characterization should encompass all biotic resources. Comparisons between impacts across geographic areas, ecosystems and temporal scales (e.g. Fig. 3) would be possible with a standardization of indicators. Considering renewability of biotic resources would allow adding a temporal element to resource depletion, as Cummings and Seager (2008) already underlined, and would help generate reliable characterization factors accounting for the sustainable use of natural biotic resources. However, there is still need of systematizing the species renewability concept (Woods et al., 2016).

Fig. 3.

Renewability rate of several naturally occurring biotic resources, expressed in Log (years).

4.2.2. Renewability-based model and associated characterization factors

According to our literature review, we identified a number of renewability indicators (see Fig. 3) to be potentially adopted in the calculation of characterization factors. It was difficult to find homogeneous renewability indicators for all biotic resources, except for fish and few other animals and plants. Therefore, by capitalizing on the available indicators and data, we selected two indicators, i.e. population doubling time for wildlife and rotation period for plants to be used as a practical example since, so far, they represent the best quantitative proxy of the key feature affecting resource availability potentials.

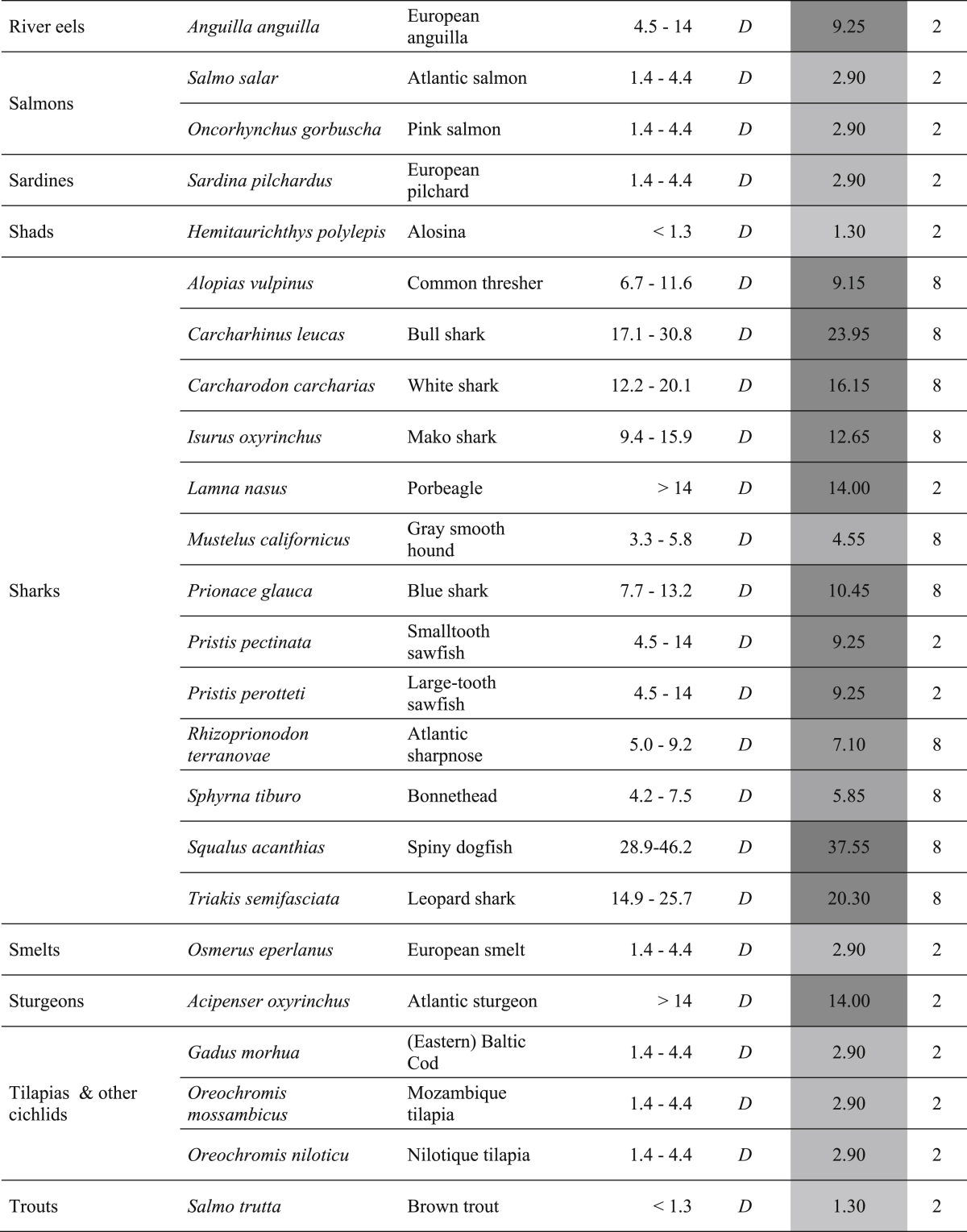

When a single value was not available, we calculated CFs (reported in Table 3) as arithmetic mean between the maximum and the minimum value of the renewal time range proposed in the retrieved literature. In several cases (e.g. brown trout; Atlantic sturgeon), due to the lack of a properly defined range of time, we used the maximum or minimum presented value as absolute average value for the calculation of CFs. In order to multiply each CF by the related elementary flow, the CF unit of measurement are in terms of years/kg and are to be multiplied by elementary flows expressed in terms of mass.

Table 3.

Examples of Characterization Factors (CFs) for NOBRri based on the mean of renewal time ranges, expressed in terms of “population doubling time” (D) and “rotation period” (R) for the most commercially valuable species. The list is presented according to the alphabetical order of commercial groups within each system (aquatic animals; terrestrial animals; terrestrial plants). Chromatic scale for CFs ranges from dark grey (lowest renewability rate) to light grey (highest renewability rate).

References: (1) Amphibian Survival Alliance, 2016; (2) Fishbase, 2016; (3) IUCN, 2016; (4) Olesiuk et al., 2005; (5) US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2016; (6) GBIF, 2016; (7) Naturalis Biodiversity centre, 2016; (8) Camhi et al., 2009; (9) Shelley and Lovatelli, 2012; (10) WCT, 2016; (11) Storch et al., 1990; (12) ADW, 2016; (13) DAISIE, 2016; (14) COSEWIC, 2016; (15) Grzimek, 1975; (16) US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2005; (17) Deinet et al., 2013; (18) Langvatn and Loison, 1999; (19) The Northeast Deer Technical Committee, 2016; (20) Spiecker and Hein, 2009; (21) WDNR, 2015; (22) Klimo and Hager, 2001; (23) DeStefano et al., 2001; (24) Dey et al., 1996; (25) PFAF, 2016; (26) Bassam, 2013; (30) Frelich and Reich, 1995; (27) Nicolescu et al., 2009; (28) Ladrach, 2009; (29) United States Forest Service, 1975; (30) Frelich and Reich, 1995; (31) Martin and Lorimer, 1997.

The resulting indicator is called NOBRri, namely Naturally Occurring Biotic Resource renewability indicator.

The evaluation of the renewal time is only one feature related to the concept of ecosystems' carrying capacity. However, it allows characterizing natural resources with an indication of the potential time-related constraints associated with their provision, ranking e.g. different species inside a kingdom. However, it is worth noting that the resulting CFs could be used at this stage for hotspots analysis only, when comparing biotic resources coming from different kingdoms (e.g. plant and animals). The hotspots would help identify resources which are longer available to be used by humans. However, among different kingdoms, CFs are not fully comparable, considering that they quantify different ecological aspects for the mentioned naturally occurring biotic resources. Indeed, this limitation is dictated by several aspects: (i) the fact that there is no functionally comparability between the aquatic and terrestrial systems since resources are principally affected by different factors (e.g. removal from the original stock vs land use changes, respectively); and (ii) the fact that natural biotic resources we considered, such as animals and plants, are taxonomically distant. The concept of renewability for a plant species may not match with the renewability for an animal species. This happens because the calculation of their renewability is based on different ecosystemic aspects. However, they all may share the same unit of measurement, i.e. the renewal time in years/kg. A similar case within the LCA framework exists for the category “Human Toxicity – non cancer”, where disparate diseases having independent intrinsic characteristics are listed and characterized with the same unit of measurement. On this basis, and considering the missing of accounting of spatial aspects in CFs when coming to measure the renewability of biotic resources' stocks, it results necessary to deepen the research for a common indicator, which could measure a consistent and coherent aspect of renewability.

5. A research agenda for improving accounting and characterization of naturally occurring biotic resources

Several steps are to be considered in order to cover the conceptual and methodological gaps in the accounting and the impact assessment of natural biotic resources within the LCA framework. Characterization -aiming at covering the “Natural Resource” area of protection- should be focused on measuring potential constraints to the availability of resources, ensuring a sustainable harvesting. We analyzed the issue of natural biotic resources focusing on elements that may interfere with the natural process of providing biomass. Consideration on how those interventions may lead to a depletion is based on the potential of being renewed in a relatively short time frame. On this basis, renewal or regeneration time may be adopted as a proxy, taking into consideration the current level of resource stocks. In fact, the scarcity aspect, related to current level of consumption versus availability, requires further methodological steps to be developed. Our choice of adopting the renewal time (or similar indicator) as a measure for characterizing biotic resources is a preliminary attempt to characterize possible drivers of depletion towards the more complex concept of scarcity.

A number of research gaps need to be covered by future research, as reported hereinafter.

-

•

Completeness of the inventory. Several issues are related to this aspect.. First of all, elementary flows and inventories for biotic resources are very limited in number. In order to develop future inventories for LCA studies, elementary flows related to commercially valuable and natural occurring biotic resources (i.e. resources that represent an input material in supply chains) should be developed. Moreover, information and metadata on elementary flows should be included and better defined (e.g. how to describe the resources, whether in terms of gross or net material, wet or dry weight). For example, details about the usable volumes such as the carcass weight are needed (e.g. eating 1 kg of fish requires a certain fraction of the entire fish body). Another important issue to overcome is that information is sometimes provided for commercial groups (e.g. tunas) and not for specific species. This lack of specificity may hamper the impact assessment of the biotic resource as different species within the same group may have ecologically different traits. Generally, the terminology still needs to be defined, harmonized and standardized, in order to differentiate between naturally occurring biotic resources and farmed/cultivated ones. In fact, it is necessary to identify the origin of the resources. Of course, the risk of assessing the same input material in two ways (as coming from ecosphere directly or as results of a production system) is something to be discussed and solved.

-

•

Comparability with biotic resources from the technosphere (e.g. from agriculture and livestock). Currently, resources that derive from processes along a supply chain (resource as a product) are not characterized and, when they enter a new supply chain, their use does not generate any impact on the category "resource depletion". On the other hand, a similar type of resource taken from nature (resource as an input from ecosphere) could be hypothetically characterized as done for abiotic resources from the ecosphere, and their impacts on resource depletion category will have a certain value different from zero. Research should go towards the direction of defining how to treat these apparently different resources. A key element is related to how soil is modeled for the cultivation of biotic resources. In fact, the biotic resource to be protected in agricultural production is the soil, which underpins the production and not the produced biomass (e.g. the crop).

-

•

Boundary between ecosphere and technosphere. Based on the current way adopted to assess and quantify the impact, i.e. as a transition of materials and energy from the ecosphere to the technosphere, we may face with some issues for biotic resources that need particular attention. For instance, this may be the case of the breeding, restocking and reintroduction of wild animals. In fact, it remains unclear if, in this case, resources taken from a reintroduced population are to be considered as proceeding from the ecosphere or as a product deriving from human intervention, therefore belonging to the technosphere. This issue can occur also in the case of forestry management, especially for short rotation. Hence, it becomes fundamental to identify and set the boundary between ecosphere and technosphere when coming to define natural biotic resources.

-

•

Overlaps between assessments of impacts associated with resource depletion and land use. According to our goal, i.e. the focus on resource availability and not on ecosystem quality per se, double counting of impacts is, in principle, avoided as the land use related impacts are focusing on different impact mechanisms. However, both land use change when exploiting a resource and the overexploitation itself may lead to biodiversity impacts. Moreover, there are several naturally occurring biotic resources which are not related to a land use occupation or transformation (e.g. fishing) or others which are used in concomitance with other land uses (e.g. harvesting herbs in forest for pharmaceutical uses may be barely related with “forest occupation” as we usually address it in LCA – using the forest for exploiting wood).

-

•

Paradoxes. While certain biotic resources are affected by the removal from their available stock (e.g. fish stocks), other resources (such as some terrestrial animals) may suffer the most for the loss of habitat, which is actually associated with impacts from land-use category rather than properly resource removal and consequent stock depletion. The CFs that we proposed are based on the same criteria of depletion both for aquatic and terrestrial systems. However, substantial differences between the two environments exist, that are not negligible.

-

•

Alien and invasive species. Within the database, we included a specific focus on environmental aspects about alien and invasive species. We felt that considering the alienness and invasiveness of species might be a key element to approach life cycle of biotic resources and their impact assessment. In fact, alien and invasive species may represent a threat to the availability and renewability of the most marketable existing species worldwide. For instance, Oreochromis spp. (i.e. O. mossabicus and O. niloticus), which are addressed as invasive species (GISD, 2016), are exerting significant pressures on water ecosystems because of their aggressiveness, high fecundity rate and resistance to poor water quality and infectious diseases. Therefore, the likelihood of their occurrence and the potential effects on native species should be considered carefully in a framework of impact assessment.

-

•

Spatial and temporal dimensions. Compiling the database (Table S3) allowed us to outline the temporal and spatial issues associated with commercial wild annual species, especially when coming to plants. In this case, the differences in the temporal scales between technosphere and ecosphere are evident. Technosphere processes, which are analyzed by an LCA study, act on a static anthropocentric equilibrium without taking into account the interactions with the ecosystem; whereas ecosphere processes follow a dynamic equilibrium (i.e. in constant change) (Commoner, 1972). Matricaria chamomilla (common name: chamomile) can be presented as a tangible example of the temporal and spatial paradoxes which involve natural biotic resources in LCA. This wild species is a naturally occurring annual herb, generally harvested for its medicinal properties. Its growth and availability depends on its interactions with the ecosystem, in particular with soil and nutrients, and with its vulnerability to natural disasters like fires and pests. Therefore, any change in ecosystem quality, soil components and nutrient cycle may generate variations on annual availability and physico-chemical properties of chamomile (Harborne, 1982). This evolving status of nature, which is not currently taken into account in the LCA-based “static” system, should be considered in future modeling.

-

•

Spatial definition of CFs. The pressures exerted by human interventions on biotic resources may depend on their localization in space. Particularly, the availability of biotic resources may depend on a combination of factors, among others the magnitude of human pressures (e.g. the rate of harvesting) and the geographic area where the resources are localized. For instance, the same species may react in different ways to impacts of the same magnitude but localized in different geographical areas, due to the size of the biotic resource stock and their stability. Therefore, when dealing with the proposal of CFs for biotic resources, it becomes important to account for the location specificity of impacts.

-

•

Non-linearity of impacts. Populations undergo natural fluctuations in abundance and would become severely depleted (ultimately leading to local extinctions) under a constant-catch strategy. In fact, it becomes an issue including such a non-linear growth rate in the LCA system, which presumes the linearity of production scale and of environmental impacts. Therefore, it should be important taking into consideration the current level of consumption versus availability.

-

•

Ecological features. According to the pressures put by human interventions, an additional step that should be taken into account is related to the importance of considering the ecological conservation status of species. On this basis, the CFs values proposed could be then weighted by considering the vulnerability of the species, for example according to the IUCN red list values (IUCN, 2016). In fact, renewability is just one of the elements affecting availability of resources; other ecological features such as resistance, resilience, vulnerability, etc. may play a role and should be taken into consideration in order to avoid compromising the natural system.

-

•

Globalization and international trade. In a globalized economy, where imports and exports represent the ordinary way of sharing products and services, another important step to be overcome to devise a valid pathway for characterizing impacts on natural biotic resources is to understand to what extent the trade of products on a global scale generates impacts on natural biotic resources. Global trade has been addressed as a potential source of biodiversity threats by several studies (Lenzen et al., 2012) and impacts on the environment associated to globalized supply chains are generally known; however the impact on species extracted as resources (e.g. to what extent a forest is affected by the removal of a plant for extracting wood) and the impact on species that are secondarily put at risk as a consequence of another resource extraction (e.g. to what extent a populations of forest birds are affected by the extraction of a tree for wood) are not clear nor quantified. Moreover, it is important to understand this aspect in order to incorporate these details in the LCA of products and services in view of a sustainable and equitable economy at global level.

6. Conclusions

Human population derives many essential goods from natural ecosystems, including seafood, game animals, wood, herbs for domestic and industrial processes, cosmetics and pharmaceutical products. These goods represent a fundamental part of the global economy and an important life-support for human societies. In a world where growing population is consuming natural resources at an unprecedented scale and pace, it is clear that there is the need to go towards the direction of a sustainable development according to the Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2016). European policies promote the efficient use of resources and set the need to manage natural biotic resources in order to ensure sustainable production, distribution and consumption of biomass. In light of this, a more specific accounting of natural biotic resources, in particular those naturally occurring in the ecosphere, is necessary to be improved. In fact, the impacts associated with these resources are barely covered in life cycle inventories, also due to the urgent need of clarifying the boundaries between ecosphere and technosphere in LCA. Besides, a consistent and robust impact assessment scheme, which evaluates how much our market demands influence and endanger the availability of natural resources, needs to be developed.

In this study, we reached the target of improving the inventory of naturally occurring biotic resources, by identifying and listing the most commercially valuable species, which could be entered as elementary flows in LCA inventories. Terminology still needs to be defined, harmonized and standardized and the list needs to be evidently implemented with additional information, such as those about usable volume. We acknowledge that it is unrealistic to develop a fully comprehensive list of resources; however, consultations with experts are crucial in order to build a reliable database.

Additional research is needed in order to overcome the issue related to the heterogeneity of indicators, and to address their feasibility in describing the impacts on resource availability within the LCA context. For example, future efforts should be made in order to understand how to deal with resources of different nature (such as plants versus animals).

In this study, through the proposal of the new indicator based on renewability, i.e. NOBRri, we identified the notable potential of using renewability time as a basis for calculating the characterization factors for biotic resources and their depletion. Undoubtedly, more research is needed in this field and the collaboration between different disciplines (e.g. ecology, engineering, etc.) is required in order to make progress towards an impact assessment model and framework fully implementable in LCA.

In our opinion, this work could be the basis for a coherent framework for improving the modeling of biotic resource in life cycle assessment, a step needed to ensure that the methodology comprehensively accounts for crucial elements of environmental sustainability.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank two JRC colleagues, Alessandro Cerutti and Luca Zampori, for their time and dedication in discussing the key concepts presented in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.208.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Alvarenga R.A., Dewulf J., Van Langenhove H., Huijbregts M.A. Exergy-based accounting for land as a natural resource in life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013;18(5):939–947. [Google Scholar]

- Amphibian Survival Alliance Amphibiaweb database. 2016. http://amphibiaweb.org Available at:

- Animal Diversity Web (ADW) 2016. University of Michigan Database on Animal Diversity.http://www.animaldiversity.org Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson R., Fransson K., Fröling M., Svanström M., Molander S. Energy use indicators in energy and life cycle assessments of biofuels: review and recommendations. J. Clean. Prod. 2012;31:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bach V., Berger M., Finogenova N., Finkbeiner M. Assessing the availability of terrestrial biotic materials in product systems (BIRD) Sustainability. 2017;9(1):137. [Google Scholar]

- Bais A.L.S., Lauk C., Kastner T., Erb K. Global patterns and trends of wood harvest and use between 1990 and 2010. Ecol. Econ. 2015;119:326–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bassam N.E. Routledge; 2013. Energy Plant Species: Their Use and Impact on Environment and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Camhi M.D., Pikitch E.K., Babcock E.A. vol. 15. John Wiley & Sons.3; 2009. (Sharks of the Open Ocean: Biology, Fisheries and Conservation). [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) 2016. Wildlife Species Assessment Meeting, April 2016.http://www.cosewic.gc.ca/eng/sct5/index_e.cfm Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Commoner B. 1972. The Closing Circle; Nature, Man, and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings C.D., Seager T.P. 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment. 2008. Estimating exergy renewability for sustainability assessment of corn ethanol; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Curran M., de Baan L., De Schryver A.M., van Zelm R., Hellweg S., Koellner T., Sonnemann G., Huijbregts M.A. Toward meaningful end points of biodiversity in life cycle assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;45(1):70–79. doi: 10.1021/es101444k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin C.G., Parker J.P. Foundations of resilience thinking. Conserv. Biol. 2014;28(4):912–923. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deinet S., Ieronymidou C., McRae L., Foppen R.P., Collen B., Böhm M. BirdLife International and the European Bird Census Council; London, UK: ZSL: 2013. Wildlife comeback in Europe: The recovery of selected mammal and bird species. Final report to Rewilding Europe by ZSL. ISBN (online): 978–0–900881–74–9, 312 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Delivering Alien Invasive Species Inventories for Europe (DAISIE) Database on biological invasion in Europe. 2016. http://www.europe-aliens.org/ Available at:

- DeStefano S., Craven S.R., Ruff R.L., Covell D.F., Kubisiak J.F. 2001. A Landowner's Guide to Woodland Wildlife Management. 68 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Dewulf J., Bösch M.E., Meester B.D., Vorst G.V.D., Langenhove H.V., Hellweg S., Huijbregts M.A. Cumulative exergy extraction from the natural environment (CEENE): a comprehensive life cycle impact assessment method for resource accounting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41(24):8477–8483. doi: 10.1021/es0711415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewulf J., Benini L., Mancini L., Sala S., Blengini G.A., Ardente F., Recchioni M., Maes J., Pant R., Pennington D. Rethinking the area of protection ‘natural resources’ in life cycle assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49(9):5310–5317. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey D.C., Johnson P.S., Garrett H.E. Modeling the regeneration of oak stands in the Missouri Ozark Highlands. Can. J. For. Res. 1996;26(4):573–583. [Google Scholar]

- Ecoinvent . 2016. Ecoinvent Database, Version 3.3.http://www.ecoinvent.org/database/ecoinvent-33/new-data-in-ecoinvent-33/new-data-in-ecoinvent-33.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson A., Ziegler F., Pihl L., Sköld M., Sonesson U. Accounting for overfishing in life cycle assessment: new impact categories for biotic resource use. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014;19(5):1156–1168. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC) 2005. Communication from the Commission - Biomass Action Plan COM (2005)628 Final. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC) 2010. Communication from the Commission - EUROPE 2020: a Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. COM(2010) 2020 Final. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC) 2012. Communication from the Commission - Innovating for Sustainable Growth: a Bio-economy for Europe. COM(2012) 60 Final. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC) 2014. Communication from the Commission - on the Review of the List of Critical Raw Materials for the EU and the Implementation of the Raw Materials Initiative. COM (2014)297 Final. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission - Joint Research Centre (EC-JRC) 2011. International Reference Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) Handbook. Recommendations for Life Cycle Impact Assessment in the European Context. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission - Joint Research Centre (EC-JRC) 2016. Environmental Footprint -Update of Life Cycle Impact Assessment Methods.http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/smgp/pdf/JRC_DRAFT_EFLCIA_resources_water_landuse.pdf draft for consultation available at: [Google Scholar]

- European Union (EU) 2009. Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. [Google Scholar]

- European Union (EU) 2009. Directive 2009/30/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 as Regards the Specification of Petrol, Diesel and Gas-oil and Introducing a Mechanism to Monitor and Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat . 2016. European Statistics on Biomass.http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/environmental-data-centre-on-natural-resources/natural-resources/raw-materials/biomass Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Federation of Associations for Hunting and Conservation of the European Union (FACE) 2016. Artemis: the Information Portal of Huntable Species in Europe.http://www.artemis-face.eu/about-the-database Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Fishbase . 2016. FishBase - a Global Information System on Fishes.http://www.fishbase.org/home.htm Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 2016. Global Statistical Collections on Fisheries and Aquaculture.http://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/en Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) FAOSTAT-Forestry online database. Available at. 2016. http://www.fao.org/forestry/statistics/84922/en/

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 2016. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture – Contributing to Food Security and Nutrition for All. 204 pp. ISBN 978-92-5-109185-2. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 2016. State of the World's Forests – Forests and Agriculture: Land-use Challenges and Opportunities. 126 pp. ISBN 978-92-5-109208-8. [Google Scholar]

- Frelich L.E., Reich P.B. Spatial patterns and succession in a Minnesota southern-boreal forest. Ecol. Monogr. 1995;65(3):325–346. [Google Scholar]

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), 2016. Available at: http://www.gbif.org/. Accessed in June 2016.

- Global Footprint Network . 2016. The Ecological Footprint.http://www.footprintnetwork.org/en/index.php/GFN/page/footprint_basics_overview/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2016. Online Database on Alien and Invasive Species that Negatively Impact Biodiversity.http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Grzimek B. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.; New York, NY: 1975. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. [Google Scholar]

- Harborne G. Academic Press; London: 1982. Introduction to Ecological Biochemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Hélias A., Langlois J., Fréon P. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment in the Agri-food Sector (LCA Food 2014), San Francisco, California, USA, 8-10 October, 2014. American Center for Life Cycle Assessment; 2014. Improvement of the characterization factor for biotic-resource depletion of fisheries; pp. 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood V. Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); 1999. Use and Potential of Wild Plants in Farm Households. No. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Hinterberger F., Giljum S., Hammer M. International Society for Ecological Economics; 2003. Material Flow Accounting and Analysis (MFA): a Valuable Tool for Analyses of Society-nature Interrelationships. Internet Encyclopedia of Ecological Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings J.A. Collapse and recovery of marine fishes. Nature. 2000;406(6798):882–885. doi: 10.1038/35022565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Standard Organization (ISO) 2006. Environmental Management – Life Cycle Assessment – Principles and Framework. ISO:14040. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) The IUCN red list of threatened species. 2016. http://www.iucnredlist.org/ Available at:

- Karabulut A.A., Crenna E., Sala S., Udias A. A proposal for the integration of the Ecosystem-Water-Food-Land-Energy (EWFLE) nexus concept into the life cycle assessment: a Synthesis Matrix for food security. J. Clean. Prod. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmit D., Mansourian S., Wildburger C., Purret A. 2016. Illegal Logging and Related Timber Trade - Dimensions, Drivers, Impacts and Responses: a Global Scientific Rapid Response Assessment Report. 37–59. [Google Scholar]