Abstract

Odontogenic tumors are a heterogeneous group of lesions of diverse clinical behavior and histopathologic types, ranging from hamartomatous lesions to malignancy. Because odontogenic tumors arise from the tissues which make our teeth, they are unique to the jaws, and by extension almost unique to dentistry. Odontogenic tumors, as in normal odontogenesis, are capable of inductive interactions between odontogenic ectomesenchyme and epithelium, and the classification of odontogenic tumors is essentially based on this interaction. The last update of these tumors was published in early 2017. According to this classification, benign odontogenic tumors are classified as follows: Epithelial, mesenchymal (ectomesenchymal), or mixed depending on which component of the tooth germ gives rise to the neoplasm. Malignant odontogenic tumors are quite rare and named similarly according to whether the epithelial or mesenchymal or both components is malignant. The goal of this review is to discuss the updated changes to odontogenic tumors and to review the more common types with clinical and radiological illustrations.

Keywords: Odontogenic tumors, odontogenesis, update, ameloblastoma, odontomas

Introduction

Odontogenic tumors (OT) are a heterogeneous group of lesions of diverse clinical behavior and histopathologic types, ranging from hamartomatous lesions to malignancy. OT are derived from ectomesenchymal and/or epithelial tissues that constitute the tooth-forming apparatus. Like normal odontogenesis, the odontogenic tumors represent inductive interactions between odontogenic ectomesenchyme and epithelium (1, (2). Therefore OT are found within the jaw bones (central types) or in the mucosal tissue overlying tooth-bearing areas (peripheral types). OT are basically divided into two primary categories; malignant and benign but the etiology is unknown. The majority of benign odontogenic tumors seem to arise de novo, whereas the malignant odontogenic tumors may arise de novo but more often arise from their benign precursor. The classification of odontogenic tumors is essentially based on interactions between odontogenic ectomesenchyme and epithelium. This dynamic classification is constantly renewed with the addition of new entities, and the removal of some older entities. The last update of these tumors was published in early 2017 (3). Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the changes of odontogenic tumors from the first WHO classification to date (3, 4, 5). In this review, we discuss odontogenic tumors relative to the latest updates and focus on the more common tumors with clinical and radiological illustrations.

Table 1.

Historically WHO benign odontogenic tumor classification from 1971 to 2017. Please note that origin based sub-classification (epithelial, mixed and mesenchymal), which is still in use in 2017, was first defined in 1992.

| 1971 WHO classification | 1992 WHO classification | 2005 WHO classification | 2017 WHO classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ameloblastoma | Epithelial origin | Epithelial origin | Epithelial origin |

| Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor | Ameloblastoma | Ameloblastoma, solid / multicystic type | Ameloblastoma |

| Ameloblastic fibroma | Squamous odontogenic tumor? | Ameloblastoma, extraosseous / peripheral type | Ameloblastoma, unicystic type |

| Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (adeno-ameloblastoma) | Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (Pindborg tumor) | Ameloblastoma, desmoplastic type | Ameloblastoma, extraosseous/peripheral type |

| Calcifying odontogenic cyst | Clear cell odontogenic tumor | Ameloblastoma, unicystic type | Metastasizing (malignant) ameloblastoma |

| Dentinoma | Squamous odontogenic tumor | Squamous odontogenic tumor | |

| Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma | Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor | Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor | |

| Odonto-ameloblastoma | Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor | Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor | |

| Complex odontoma | Keratocystic odontogenic tumor | ||

| Compound odontoma | Mixed origin | Mixed origin | Mixed origin |

| Fibroma (odontogenic fibroma) | Ameloblastic fibroma | Ameloblastic fibroma | Ameloblastic fibroma |

| Myxoma (myxofibroma) | Ameloblastic fibrodentinoma (dentinoma) and ameloblastic fibro-odontoma? | Ameloblastic fibrodentinoma | Primordial odontogenic tumor |

| Cementomas | Odontoameloblastoma | Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma | Odontoma, Complex type |

| a. Benign cementoblastoma (true cementoma) | Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor | Odontoma, Complex type | Odontoma, Compound type |

| b.Cementifying fibroma | Calcifying odontogenic cyst | Odontoma, Compound type | Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor |

| c. Periapical cemental ysplasia (periapical fibrous dysplasia) | Complex odontoma | Odontoameloblastoma | |

| d. Giganti form cementoma (familial multiple cementomas) | Compound odontoma | Calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor | |

| Melanotic neuro-ectodermal tumor of infancy | Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor | ||

| Mesenchymal origin | Mesenchymal origin | Mesenchymal origin | |

| Odontogenic fibroma | Odontogenic fibroma | Odontogenic fibroma | |

| Myxoma (odontogenic myxoma, myxofibroma) | Odontogenic myxoma / myxofibroma | Odontogenic myxoma/myxofibroma | |

| Benign cementoblastoma | Cementoblastoma | Cementoblastoma | |

| Cemento-ossifying fibroma |

Table 2.

Historically WHO malign odontogenic tumor classification from 1971 to 2017.

| 1971 WHO classification | 1992 WHO classification | 2005 WHO classification | 2017 WHO classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odontogenic carcinomas | Odontogenic carcinomas | Odontogenic carcinomas | Odontogenic carcinomas |

| Malignant ameloblastoma | Malignant ameloblastoma | Metastasizing (malignant) ameloblastoma | Ameloblastic carcinoma |

| Primary intra-osseous carcinoma | Primary intraosseous carcinoma | Ameloblastic carcinoma - primary type | Primary intraosseous carcinoma |

| Other carcinomas arising from odontogenic epithelium, including those arising from odontogenic cysts | Malignant variants of other odontogenic epithelial tumors | Ameloblastic carcinoma-secondary type, intraosseous | Sclerosing odontogenic carcinoma |

| Odontogenic sarcomas | Malignant changes in odontogenic cysts | Ameloblastic carcinoma-secondary type, peripheral | Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma |

| Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma (ameloblastic sarcoma) | Odontogenic sarcomas | Primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma - solid type | Ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma |

| Ameloblastic odontosarcoma | Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma (ameloblastic sarcoma) | Primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma derived from keratocystic odontogenic tumor | Odontogenic carcinosarcoma |

| Ameloblastic fibrodentino-and fibro-odontosarcoma | Primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma derived from odontogenic cysts | Odontogenic sarcomas | |

| Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma | |||

| Ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma | |||

| Odontogenic sarcomas | |||

| Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma | |||

| Ameloblastic fibrodentino-and fibro-odontosarcoma |

Odontogenic benign tumors, epithelial

Ameloblastoma

Ameloblastoma is a benign but locally aggressive epithelial neoplasm that is one of the most common odontogenic tumors. Current genetic studies show mutations in genes that belong to MAPK pathway in many ameloblastomas. BRAFV600E is the most common mutation (6). WHO 2017 classification divided ameloblastoma into four categories; conventional, extraosseous / peripheral, unicystic, and metastasizing ameloblastoma.

Clinical features

Conventional ameloblastoma usually shows slow, painless expansion (Figure 1). The posterior area of mandible is the most common location. They tend to grow in a buccolingual direction, resulting in significant expansion. The signs and symptoms are variable; including malocclusion, facial deformity, soft tissue invasion or loosening of teeth depends on the size of the lesion. The mean age is about 35 years, ranging from 4 to 92. Radiographically, a corticated multilocular radiolucency is common (Figure 2), however a unilocular appearance may be seen (7). different histopathologic subtypes, however none of them affect prognosis. Only the desmoplastic type has different clinical features, including a radiolucentradiopaque appearance, and predilection for the anterior jaws, especially maxilla (8). Unicystic ameloblastoma is a subtype of intraosseous ameloblastoma, consisting of a large single cyst. They tend to present a decade earlier than conventional ameloblastoma and radiographs often show a unilocular, well-demarcated radiolucency that surrounds the crown of the unerupted tooth, resembling dentigerous cysts (Figure 3). The ameloblastoma can grow into the lumen that is called the ‘intraluminal type’ or it can only be confined to the cyst lining epithelium, which is also called the ‘luminal type’. If ameloblastoma invaded the wall of the cyst, it was called ‘mural type’ in the 2005 3rd edition. This is one of the significant changes to the new classification because unicystic ameloblastomas have been traditionally treated conservatively, often by “cyst” enucleation, and recurrence has been uncommon. However, there is emerging evidence that unicystic ameloblastomas with mural invasion are known to act as conventional intraosseous ameloblastoma and should be treated as such (9). Extraosseous (peripheral) ameloblastoma is a conventional ameloblastoma seen exclusively in the soft tissues of gingiva (Figure 4). Gingival extension of an intrabony ameloblastoma must be ruled out radiographically. Clinically, it is not distinguishable from other mucosal nodular lesions. The lesions mostly occur in the premolar region of the mandible, followed by the tuberosity region of maxilla. In the 2017 WHO classification, metastatic ameloblastoma was moved to the benign ameloblastoma subtypes from the malignant odontogenic tumors. The most important reason for this is both the primary and metastatic ameloblastomas are histopathologically identical to benign ameloblastoma. It occurs very rarely and none of the histologic findings observed in the primary tumor are specific for predicting metastasis. It can only be diagnosed after it has metastasized, most often to lung. Metastatic ameloblastomas are observed in the age range of 4-75 years with an average age of 30 years. The majority of cases are diagnosed 10 years after the first treatment (10, 11). This emphasizes the importance of ameloblastoma follow-up. The decision to move metastatic (malignant) ameloblastoma in the 2005 edition to the benign ameloblastomas in the 2017 edition was controversial and not unanimously agreed upon.

Figure 1.

Ameloblastoma. Often presents with cortical expansion.

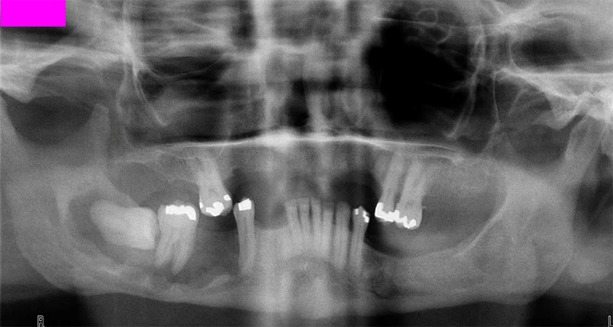

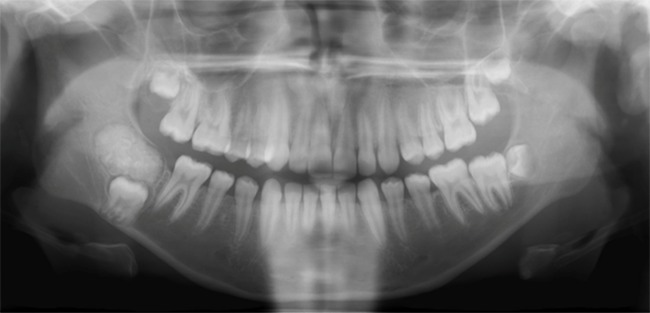

Figure 2.

Ameloblastoma. Typical multilocular radiographic features.

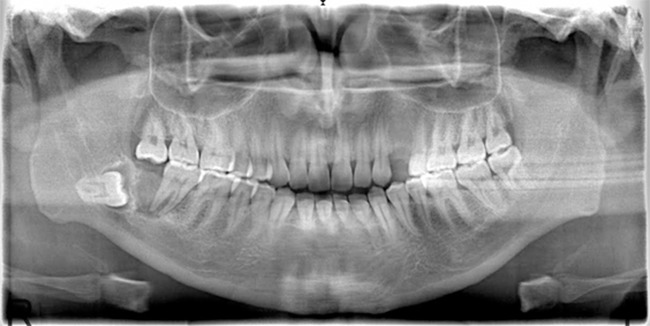

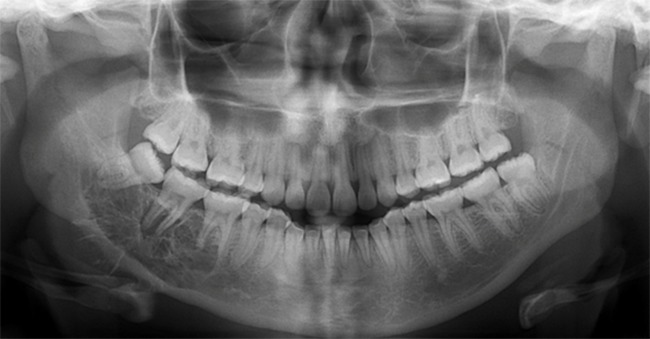

Figure 3.

Unicystic ameloblastoma. Often occurs in younger patients and like a dentigerous cyst radiographically.

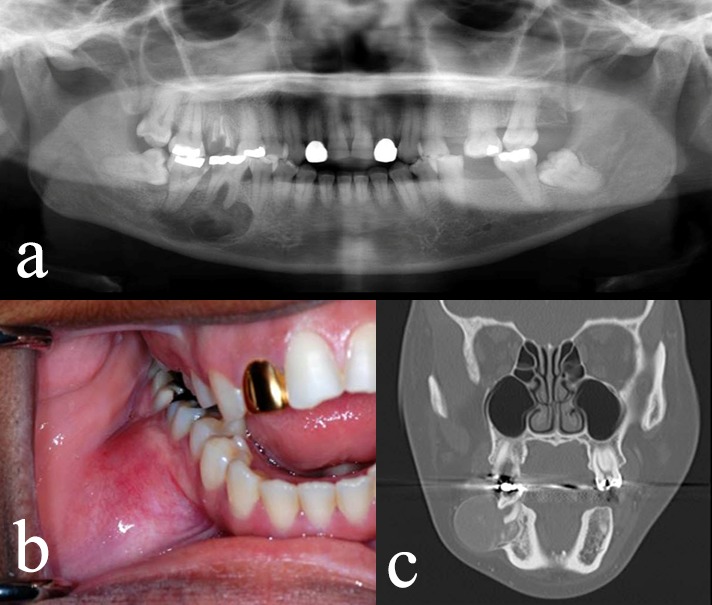

Figure 4.

Extraosseous ameloblastoma. Mucosal nodular lesion.

Histopathology

Histopathologically, ameloblastoma tends to have cystic changes which is often seen microscopically and even appreciated macroscopically in some cases. Many microscopic subtypes have been identified. However, it is known that they do not affect the biological behavior of the neoplasm. Follicular and plexiform types are the most common. There are also acanthomatous, granular cell, desmoplastic and basal cell types. The desmoplastic type was previously speculated to be more aggressive, but this was not conclusively proved with additional publications. The 2017 WHO classification, therefore, moved desmoplastic ameloblastoma to a histologic subtype without biological significance. Two types of cells are observed histopathologically in ameloblastoma. The first is columnar cells resembling normal ameloblasts that palisade around the epithelial islands, and the second are the more centrally located cells that resemble the stellate reticulum (12). Unicystic ameloblastoma is usually diagnosed after histopathologic examination because it appears like an odontogenic cyst both clinically and radiologically.

Treatment and prognosis

The treatment of conventional ameloblastomas is wide surgical excision with 1.5 cm margins (13). Conservative surgery results in a high recurrence rate. Unicystic ameloblastomas are less aggressive and are often treated with enucleation. In the WHO classification of 2017, it has been recommended that a mural type case should be treated as a conventional ameloblastoma if it recurs (3). Extraosseous ameloblastoma has different biologic behavior and conservative removal with free margins is warranted. Long- term follow up is necessary. Recurrence may occur 10 years or longer after initial surgery.

Squamous odontogenic tumor

Squamous odontogenic tumor is a benign epithelial tumor that is very rare among odontogenic tumors. The tumor is usually intraosseous, but several peripheral cases have been reported in the literature.

Clinical features

It is seen equally in the mandible and maxilla in a wide range of ages from childhood to the eighties. Maxillary lesions are mostly located in the anterior region; whereas mandibular lesions are located in the posterior region. Radiographically, they present as a unilocular radiolucency (Figure 5), often characterized by triangular shape between the teeth in the lateral direction of a tooth (14, 15).

Figure 5.

Squamous odontogenic tumor of the right mandible.

Histopathology

Histopathologically, mature squamous epithelial islands of varying shape and size are observed within a mature fibrous connective tissue. The cells around the islands do not show palisading or reverse polarization that is characteristic of ameloblastomas. Microcystic change and typical individual cell keratinization may occur in the islands. Squamous odontogenic tumorlike islands can be observed in the wall of odontogenic cysts but it does not affect the prognosis.

Treatment and prognosis

Curettage, enucleation, or local excision is usually adequate treatment. Recurrence has been reported rarely (14, 15).

Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor

Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor is a benign epithelial odontogenic tumor. These tumors constitute approximately 2-7% of all odontogenic tumors that are biopsied. Intraosseous and extraosseous types are described. Because of limited growth, the tumor is considered to be a hamartoma by many researchers.

Clinical features

The age range varies from 5 to 30, with a second decade peak. Female/male ratio is 2:1. The lesion is most commonly located in the anterior region of the maxilla associated with unerupted teeth. Radiologically, it is usually a well-demarcated unilocular radiolucency, but occasionally with small flecks of opacity internally. The tumor can be divided into two clinical types; follicular and extrafollicular. The most common type (73%) is the follicular type where there is a well-defined unilocular radiolucency surrounding an unerupted tooth crown; radiographically identical to a dentigerous cyst (Figure 6). The extrafollicular type (24%) is seen as a well-defined radiolucency which can be superimposed on the roots of a tooth that therefore, can often be misdiagnosed as an odontogenic cyst. The peripheral or extraosseous type is less common type (3%) (16, 17, 18).

Figure 6.

Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Classic radiographic presentation, unilocular radiolucency around the crown of an unerupted tooth in the anterior maxilla.

Histopathology

Generally, there is a thick, fibrotic capsule around the lesion. The tumor on cross-section may contain solid or cystic changes. The solid areas consist of multiple, variably sized nodules of spindled epithelial cells. Columnar epithelial cells form rosette /ductlike structures that are hollow in the middle. These structures are characteristic, but may be dominant or sometimes not observed at all. Glandular elements are absent. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor-like areas can be observed in other odontogenic tumors, including odontoma and calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor.

Treatment and prognosis

Simple enucleation is the most common treatment method. Although recurrent cases have been reported, this usually occurs due to in complete excision (18). Its clinical behavior is more like hamartomas than neoplasms.

Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (Pindborg Tumor)

Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (CEOT) is a relatively rare benign epithelial odontogenic tumor. It is characterized by secreting a unique amyloid protein which is called ‘odontogenic ameloblastic associated protein’ (19) which often calcifies. There are peripheral and intraosseous types. Approximately 6% of cases are peripheral (20).

Clinical features

CEOTs are most often seen as a painless, slow growing swelling. The tumor presents over a range of ages with a mean age of 40 years. There is no sex predilection. Approximately 2/3 of the cases are located in the posterior region of the mandible. The peripheral type presents as a gingival mass which allows it to be diagnosed a few years earlier than the intraosseous type. Radiographically, they can show different stages; only radiolucent or radiolucentradiopaque areas or dense radiopaque images. Lesions are mostly unilocular however it can be multilocular. It may contain calcification areas within the radiolucent area. About 50% of the cases are associated with an unerupted tooth (20, 21) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor. A mixed radiolucent-radiopaque lesion with an unerupted tooth at the right posterior of mandible.

Histopathology

The tumor consists of polyhedral epithelial cells that exhibit distinct islands, cords and trabeculae. The stroma may be fibrotic. Sometimes cellularity is more obvious and may show distinct nuclear pleomorphism. However, this appearance is not related to malignancy. Variable amounts of an eosinophilic, hyalinized extracellular accumulation of protein matrix are usually seen. This material is the amyloid protein called odontogenic ameloblast-associated protein (ODAM) which reacts with Congo red stain (19). This material calcifies, resulting in the round concentric calcifications termed ‘Liesegang rings’ which are typical for the tumor. In some cases these small calcifications combine to form large masses (20, 21). The histopathology of the peripheral type is similar to the intraosseous type.

Treatment and prognosis

The treatment is local surgical removal with tumor-free margins. The maxillary lesion tends to recur, with an overall recurrence rate of about 15%. Conservative excision is adequate for the peripheral variant (19, 20, 21).

Odontogenic benign tumors, mixed

Ameloblastic fibroma

Ameloblastic fibroma is a rare, mixed odontogenic tumor composed of dental papilla-like odontogenic ectomesenchyme and odontogenic epithelium. In addition to these features, ‘ameloblastic fibrodentinoma’ was used if there was dentin formation, and ‘ameloblastic fibro-odontoma’ terminology was used if both dentin and enamel were present in 2005 WHO classification (4). However, the 2017 WHO classification has emphasized that the appearance of such hard tissue formation is usually the first stage in maturation and more compatible with a developing odontoma (3).

Clinical features

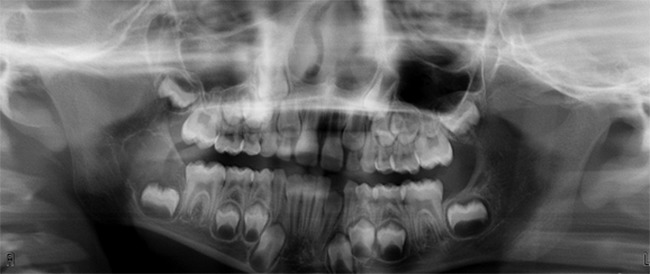

Ameloblastic fibroma is usually present as a painless, and slowly growing mass. The tumor presents most frequently in the first two decades of life with a slight male predilection. They are discovered due to disturbances of tooth eruption or incidentally during routine radiographic examination. More than 80% of the cases occur in the posterior mandible. Radiographically, the tumor presents as a well-defined unilocular or multilocular radiolucency associated with a malpositioned tooth (Figure 8) (22, 23).

Figure 8.

Ameloblastic fibroma. Pericoronal radiolucency of the right posterior mandible in a child.

Histopathology

It composed of both mesenchymal and epithelial components, both of which are considered neoplastic; hence “mixed” odontogenic tumor. The epithelial component consists of branching and anastomosing epithelial strands like dental lamina in a loose myxoid mesenchymal stroma, resembling dental papilla of the tooth bud. Collagen fibers are not observed.

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment choices are variable; most commonly conservative therapy for small and asymptomatic lesions or less commonly, aggressive surgery for extensive or local recurrent lesions. The recurrence rate is about 18%. Ameloblastic fibromas can rarely transform to ameloblastic fibrosarcoma when untreated or more commonly, following multiple local recurrences of a benign ameloblastic fibroma, with the subsequent recurrence consisting of a sarcoma. Longterm follow-up is necessary to detect recurrence and possible malignant transformation (23, 24).

Primordial odontogenic tumor

Primordial odontogenic tumor is a newly defined entity in the 2017 WHO classification. It was first described in 2014 (25). There are less than 10 cases published to date.

Clinical features

The tumor often affects patients in first two decades. Radiographically, a well-demarcated radiolucency associated with an unerupted third mandibular teeth is usually observed. It may cause displacement and resorption of adjacent teeth. The most commonly affected site is the molar region of the mandible.

Histopathology

Grossly, this very rare tumor is a multi-lobulated, solid mass without cystic change associated with an embedded tooth. Histopathologically, it is characterized by dental papillae-like, loose connective tissue with varying cellularity surrounded by a cuboidal/columnar epithelium resembling inner enamel epithelium of the enamel organ. The characteristic feature is the columnar or cuboidal epithelium covering the periphery of the tumor (26).

Treatment and prognosis

Enucleation is the treatment of choice. No recurrence has been reported to date.

Odontoma; compound and complex type

Odontomas are mixed epithelial and ectomesenchymal tumors composed of dental hard and soft tissues. They are generally regarded as a tumor-like malformations or hamartomas, rather than neoplasms. Odontomas are the most common odontogenic tumor. There are two types of odontoma; compound and complex. In complex odontoma, there is a single mass of haphazardly arranged soft and hard dental structures, whereas in compound odontomas, the hard and soft tissues are laid down in their appropriate anatomic relationships; forming small tooth-like structures (27).

Clinical features

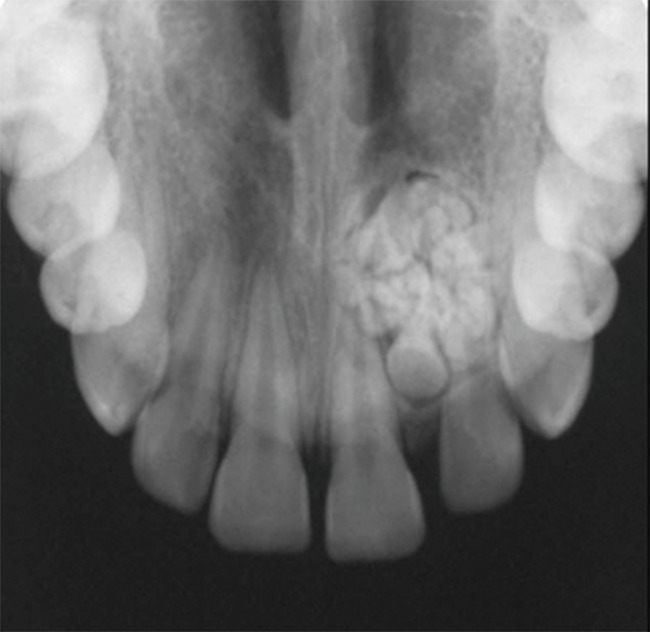

Odontomas commonly occur in the first and second decades and usually are diagnosed during routine radiographic examination. They may be detected on investigation of a tooth failing to erupt or as abnormal swelling. Compound odontomas are mainly located in the anterior maxilla and appear as a collection of tooth-like structures surrounded by a radiolucent zone (Figure 9), whereas complex odontomas radiographically are found most often in the posterior mandible and consist of a homogeneous mass of calcified tissue surrounded by a thin soft tissue capsule (Figure 10) (27, 28). Odontomas occur frequently around unerupted teeth.

Figure 9.

Compound odontoma. Small tooth-like structures with radiolucent halo representing the dental follicle in which odontomas develop.

Figure 10.

Complex odontoma. The enamel, dentin and cementum are more haphazardly arranged. Also note the radiolucent periphery.

Histopathology

Enamel, dentin, and cementum-like tissue arranged in a haphazard pattern are observed in complex odontoma; in contrast the normal anatomic structure is encountered in compound odontoma. There is usually a fibrous wall in the periphery of odontomas which represents the dental follicle in which odontomas develop.

Treatment and prognosis

Conservative surgery is an adequate treatment for odontomas. Recurrence is not observed when they are completely removed. Rarely dentigerous cysts occur in odontomas.

Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor

Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor (DGCT) is a very rare benign, but locally infiltrative mixed odontogenic tumor. It is also accepted as the solid, neoplastic form of calcifying odontogenic cyst. DGCT mostly occurs in intraosseous sites, less commonly in the soft tissue of the gingiva and alveolar mucosa.

Clinical features

The reported age of patients with the tumor ranges from 11 to 79 with a peak incidence between the 4th and 5th decades. The tumor is twice more common in males than females. The tumor occurs in the posterior maxilla and mandible, but the extraosseous variant shows a predilection for the anterior part of the jaws. Patients are usually asymptomatic. In some cases resorption of cortical bone with extension into soft tissues can be observed. The extraosseous variant presents as a sessile, sometimes pedunculated, exophytic nodule of the soft tissue. Radiographically, most of the tumors show a unilocular, radiolucent to mixed radiolucent/radiopaque appearance depending on the amount of calcification (Figure 11). They may be multilocular (29, 30, 31).

Figure 11.

Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor. Mixed radiolucent/radiopaque pericoronal lesion of left posterior mandible.

Histopathology

Both intra- and extra- osseous types show similar histopathology. The basic histopathological feature is the presence of ameloblastoma-like islands. Minor cysts might form in the epithelial islands. A characteristic feature is the transformation of the epithelial cells into ghost cells. Some ghost cells undergo calcification. DGCTs produce dysplastic dentin or osteodentin-like material. Ghost cells may be trapped in this dysplastic dentin, which in some areas may be mineralized.

Treatment and prognosis

There is no optimal treatment choice due to the small number of cases reported. Because of the potential for recurrence with conservative surgery, wide local excision should be the treatment model for the intraosseous DGCT. More conservative excision is an appropriate treatment of the extraosseous type. Long follow-up is required for recurrences that may occur years later (29, 30, 31).

Odontogenic benign tumors, mesenchymal

Odontogenic fibroma

Odontogenic fibroma is a rare, benign mesenchymal odontogenic tumor. There are intraosseous and peripheral variants with the peripheral one more common. The 2005 classification recognized two variants of odontogenic fibroma; the simple or epithelium poor variant and the WHO or epithelium rich variant. The 2007 classification has removed the simple type because it is poorly defined and recognized at this time.

Clinical features

Central odontogenic fibroma has a wide patient age range and it is relatively common in females. While the tumors of the maxilla are located in the anterior region, mandibular tumors are located mostly in the molar region. Most of the cases appear as a unilocular radiolucent area with well-defined often sclerotic borders (Figure 12), but larger tumors may become multilocular. Peripheral odontogenic fibroma presents as a gingival mass, resembling fibrous hyperplasia. The peripheral type occurs twice as often in females than males and the incidence peak is between second to fourth decades of life (32, 33).

Figure 12.

Central odontogenic fibroma. Radiolucent lesion of the right maxilla.

Histopathology

The histopathology of the peripheral type and the central type is similar. They are composed of variable amounts of small, inactive odontogenic epithelial islands/cords within cellular or collagenous connective tissue. The amount of epithelium is variable, as are calcifications.

Treatment and prognosis

Enucleation and curettage, conservative laser excision can be the treatment of central lesions and simple excision is sufficient for peripheral types. Recurrence is rare. It has been reported that recurrence occurs due to insufficient removal of the lesion (32, 33)

Odontogenic myxoma/myxofibroma

Odontogenic myxoma is the third most common odontogenic tumor after ameloblastoma and odontomas (34). The tumor is almost always located intraosseously, but peripheral types have been described (35).

Clinical features

The benign, slow growing but locally aggressive tumor is usually diagnosed in the second to fourth decades. They most commonly occur in the molar and ramus regions of the mandible. Maxillary lesions also tend to present in the posterior quadrant. Radiographically, small lesions may have a unilocular appearance. However, most lesions are multilocular radiolucencies with internal bony septa (Figure 13). These septa have been described as making a tennis racket–like or stepladder-like pattern, but this pattern is rarely seen. They are mostly fine, curved and coarse appearances (36, 37).

Figure 13.

Odontogenic myxoma. Characteristic radiolucency with fine internal opaque trabeculations of the right posterior mandible.

Histopathology

Odontogenic myxoma consists of fine delicate stellate, fusiform and round cells in a bland myxoid stroma, somewhat resembling the dental papilla of the developing tooth germ. Bony invasion may be observed. Variable amounts of collagen fibers may be present. If the collagen is abundant in the stroma, it can also be called ‘odontogenic myxofibroma’ but this designation does not have clinical or prognostic significance.

Treatment and prognosis

The treatment choice is resection with free margins. However small lesions can be treated by conservative surgery with the expectation of a low risk of recurrence. Overall the recurrence is about 25% and long-term follow-up is required (38).

Cementoblastoma

Cementoblastoma is a benign odontogenic mesenchymal tumor that is associated with and attached to the roots of teeth. It is considered to be the only true neoplasm of cemental origin.

Clinical features

Cementoblastoma is fused with a tooth root and generally presents as a slow-growing swelling, often with pain, with expansion of the affected bone. The tumor is frequently seen in the second and third decades of life and affects the molar and premolar regions of the mandible predominantly. The mandibular first molar is the most frequently affected tooth. The typical appearance on a radiograph is a large radiopaque mass in continuity with the roots from which it arose. Cementoblastomas are encapsulated and this translates radiographically as a thin, uniform lucency around the periphery of the tumor. The density of the cemental mass usually obliterates the radiopaque details of the roots. The radiographical appearance is characteristic and usually pathognomonic (39, 40) (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Cementoblastoma. Classic appearance of a sclerotic tumor fused with the tooth roots and surrounded by a thin lucent border.

Histopathology

Cementoblastoma consists of calcified cementumlike masses in a fibrovascular stroma. The middle part of the tumor is more mature and the peripheral part is more cellular. The active cementoblasts rim the trabeculae. These histopathological appearances are similar to osteoblastoma but the osteoblastoma seen in the jaws is not related to the root of a tooth.

Treatment and prognosis

Conservative treatment is curative. Incomplete removal leads to recurrence (40).

Cemento-ossifying fibroma

Ossifying fibromas were divided into 3 subtypes in the 2017 WHO classification. The first is odontogenic and designated cemento-ossifying fibroma; others are psammomatoid and trabecular juvenile types. Cemento-ossifying fibroma, also known as ossifying fibroma or cementifying fibroma, is classified under the mesenchymal odontogenic tumor group, whereas the juvenile types which are not considered odontogenic are classified under fibro- and chondroosseous lesions in the last classification.

Clinical features

Cemento-ossifying fibromas are slowly growing lesions and usually presents with painless expansion. Pain and displacement of surrounding teeth are rarely reported. The related teeth may be mobile and less frequently root resorption is seen. The tumor is often seen in the second and fourth decades of life with a mean age of 35 years with a prominent female predominance. The tumor is frequently located in premolar and molar are as of the mandible. Radiographically, there is a well-defined, unilocular radiolucency with varying amounts of opacification depending on the amount of hard tissue produced by the neoplasm (Figure 15) (41, 42).

Figure 15.

Cemento-ossifying fibroma. Radiographic features in the right posterior mandible (a) with significant buccal expansion (b and c).

Histopathology

Cemento-ossifying fibromas may be encapsulated. The tumor consists of variable amounts of calcified tissue in a hypercellular fibrovascular stroma. The calcified material can resemble bone (trabecular with cellular inclusions) or cementum (often more globular and acellular). The neoplasm does not invade adjacent bone which allows them to be easily removed. Grossly, there is often a single mass or large fragments and this feature is important clinically in the differential diagnosis of cemento-osseous dysplasias from the cemento-ossifying fibromas.

Treatment and prognosis

Conservative surgical treatment usually does not result in recurrence. Massive lesions may require en bloc resection (41).

Malignant odontogenic tumors

The malignant odontogenic tumors are rare. They all share similar clinical and radiographic features, and the distinction among this group of tumors is primarily differences in their histologic features. Things that should alert you to the possibility of a lesion being malignant include rapid growth, asymmetry, pain, paresthesia, anesthesia, and a poorly defined destructive osteolytic process. Accordingly, while this group of lesions will be discussed for completeness, only one will be illustrated (Figure 16).

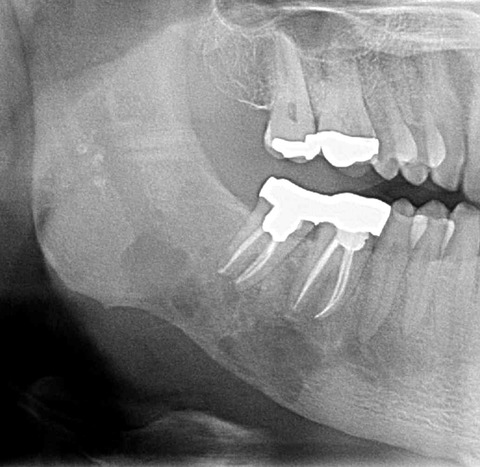

Figure 16.

Odontogenic sarcoma. This could be any of the odontogenic malignancies. Note poorly marginated, destructive lucency. The root canals were performed because the patient was in pain.

Ameloblastic carcinoma

Ameloblastic carcinoma is a rare primary malignant epithelial odontogenic tumor showing histologic features of ameloblastoma. The tumor is the malignant counterpart of ameloblastoma and has cellular atypia and the ability to metastasis. BRAF V600E mutation has been found identical to those in other ameloblastic neoplasms (43).

Clinical features

Clinically there can be swelling, pain, rapid growth, trismus and dysphonia. Most cases arise in patients older than 45 years. The tumor is frequently located in the posterior region of the mandible. Radiographically, there is an irregularly marginated radiolucency often with cortical bone perforation and/or soft tissue invasion (43, 44, 45).

Histopathology

Ameloblastoma-like appearance with cytological atypia is seen in both primary and metastatic ameloblastic carcinomas. However, the classical features of ameloblastoma including reverse polarity and peripheral palisading are usually lost. Pleomorphism, altered nuclearcytoplasm ratio, abnormal mitoses, vascular or nerve invasion are important features for the diagnosis. The presence of necrosis may be helpful. The mitotic rate is usually increased but the increase in mitotic activity alone is not valuable (44, 45).

Treatment and prognosis

The main treatment is radical surgical resection. Prognosis is quite poor. Lung metastasis develops much more commonly than locoregional lymph node metastasis (45).

Primary intraosseous carcinoma

In the 2005 classification, the primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma was divided into numerous entities based on their histogenesis. In the 2017 classification, one of the goals was simplicity and this group of lesions was incorporated as one under the umbrella of ‘primary intraosseous carcinoma’ (46). Primary intraosseous carcinoma is diagnosed only after other carcinoma types are excluded, particularly metastatic carcinomas from distant primary sites. Primary carcinomas are quite rare. They originate from the odontogenic epithelium, either from remnants left from odontogenesis, from the epithelial lining of an odontogenic cyst or other precursor epithelial lesions.

Clinical features

The clinical manifestations of the cases are not specific. Large lesions may cause cortical bone destruction and perforation. The tumor is observed in a wide age range with a mean age at diagnosis of 55-60 years. It frequently occurs in the corpus and posterior region of the mandible. Maxillary cases are mostly located in the anterior region. Radiographically, there is a radiolucent lesion with irregular cortical border (47, 48).

Histopathology

Histopathologically, almost all cases show small nests or islands of atypical squamous cells but without features of ameloblastoma. Significant keratinization is rarely seen. Usually the differentiation of the tumor is moderate. As mentioned, primary intraosseous carcinoma is a diagnosis of exclusion. The exclusion includes other malignant odontogenic carcinomas, metastatic carcinomas, intraosseous salivary gland carcinomas, and carcinomas of the maxillary region. Immunohistochemical stains are helpful in making these differences.

Treatment and prognosis

Radical resection with neck dissection is the primary treatment. Adjuvant radio- or chemotherapy can provide added benefit. Regional lymph node metastasis is not uncommon. However distant metastasis, usually to lung, is not frequent (49). The prognosis is poor. The cases arising from cysts may have a better prolonged course (50).

Sclerosing odontogenic carcinoma

Sclerosing odontogenic carcinoma, which was first described in 2008, has been added for the first time to the 2017 WHO classification. About ten cases have been reported to date (51, 52). Due to its new addition and the fact that few cases have been published, its features are not fully established.

Clinical features

The most frequent affected localization is the premolar and molar areas of the mandible with no sex predilection. Radiographically there is an ill- defined radiolucency with frequent cortical bone destruction (51, 53).

Histopathology

The hallmark of the tumor is single file cords and strands of polyhedral epithelial cells streaming within a stroma of dense sclerosis. Even though the cytological features are bland, the tumor is characterized by aggressive infiltrative growth into muscle and nerve. Given the rarity of the tumor, other odontogenic tumors and metastasis should be excluded before the diagnosis can be made.

Treatment and prognosis

Since only case reports have been reported in the literature, no specific treatment protocol has been established. It can be treated as a low-grade malignancy, therefore primary treatment is surgical resection. No metastatic cases and only one recurrent case after initial curettage have been reported to date (3).

Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma

Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma is rare, low-grade malignancy. The vast majority (88%) of the tumors has EWSR1 rearrangements detectable by fluorescent in situ hybridization (54).

Clinical features

The tumor has non-specific signs. It can cause root resorption and soft tissue invasion. However many cases are asymptomatic. The most frequently affected site is the mandible with a female predilection. Most cases occur in 4-7 decades, with a mean age of 53. Radiographically it appears as a destructive radiolucency with ill-defined margins (55, 56).

Histopathology

The tumor is characterized by predominantly sheets and islands of vacuolated and clear cells separated by a hyalinized to fibrous stroma. These cells show diastase-resistant periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) positivity and mucin-negativity that is important for the differential diagnosis of salivary gland neoplasms. The cytological features can be bland, with only mild atypia and few mitoses. Before making a diagnosis of clear cell odontogenic carcinoma, many clear cell-rich neoplasms, especially metastatic renal cell carcinoma, should be excluded (57).

Treatment and prognosis

The primary treatment is complete surgical resection. Adjuvant radiotherapy may also be considered (55).

Ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma

Ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma is an extremely rare, malignant odontogenic tumor. About 40% of the cases arise from benign, precursor ghost cell odontogenic lesions, the rest occur de novo (58).

Clinical features

The tumor has no specific signs and symptoms. All features are similar with other low grade malignancies. Slow growing, ulceration, root resorption or soft tissue invasion can be seen. Radiographically, the tumor is a destructive radiolucent lesion with ill-defined borders.

Histopathology

Ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma may arise from other benign ghost cell tumors; dentinogenic ghost cell tumor and calcifying odontogenic cysts. To make a diagnosis, it is important to observe ghost cells or precursor ghost cell lesions with pleomorphism, necrosis, and infiltrative growth pattern. Ghost cells can be varying numbers with large, pale-staining cytoplasm without nuclei. The malignant epithelial cells show sheets, strands, and islands in a fibrous stroma (58, 59).

Treatment and prognosis

Wide surgical resection is the primary treatment as with other oral carcinomas. The role of radiotherapy and aggressive multimodal therapy remain undefined (59).

Odontogenic sarcomas

Odontogenic sarcomas include a very rare group of malignant odontogenic tumors in which the epithelial component is cytologically benign, and the mesenchymal component is malignant. Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma is the most common type. If the tumor produces dentin, it can be called ‘ameloblastic fibrodentinosarcoma’ and if enamel and dentin production is present it can be called ‘ameloblastic fibro-odontosarcoma’. Because there is no evidence that these designations have implications on outcome, they were all included in the uniform category of odontogenic sarcomas in the 2017 classification. Although the etiology is not clear, it is generally thought to originate from a precursor lesion, especially ameloblastic fibroma (3, 60).

Clinical features

The tumor shows a wide patient age distribution with a mean age of 30 years. The tumor is observed most frequently in the mandible as an expansible mass that can cause pain, paresthesia and dysesthesia. Almost half of the cases in the literature have been reported to be malignant transformation of ameloblastic fibroma. The radiograph shows irregularly marginated lesions (60, 61).

Histopathologic features

Histopathology of odontogenic sarcomas shows a mixed component. The epithelial component is benign and may be as evident as a classical ameloblastic fibroma or sometimes eradicated/compressed by the malignant mesenchymal component. The mesenchymal component has malignant features, including increased mitosis, variable degrees of cellularity and cytology atypia.

Treatment and prognosis

The recommended treatment is a wide surgical excision that provides uninvolved surgical margin. The efficacy of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is controversial.

Odontogenic carcinosarcomas

Odontogenic carcinosarcomas are very rare mixed malignant tumors. There are only a few cases in the literature. In fact, it was a known entity that was excluded from the 2005 classification but was reinstituted in the 2017 classification because of better documentation with immunohistochemistry (3, 4, 62).

Clinical features

Because of the rarity of this tumor, there are no distinct clinical features. The reported cases have occurred in the mandible and the age range is 9-63 years. Radiologic examination reveals a lytic lesion with ill-defined borders (62, 63).

Histopathology

Both epithelial and mesenchymal components of the tumor are cytologically malignant. Ameloblastic islands with malignant features are observed in the stroma composed of hypercellular, pleomorphic, fibroblastic cells. High proliferation index is seen in both carcinoma and sarcoma components (64). Care must be taken to not misdiagnose a spindle cell odontogenic carcinoma as odontogenic carcinosarcoma.

Treatment and prognosis

The main treatment is surgical resection. However, due to the very limited number of cases, the prognosis and treatment choices are controversial.

Footnotes

Source of funding: None declared.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Nanci A. Ten cate’s oral histology: Development, structure, and function. 7th ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008. pp. 79–107. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilodeau EA, Collins BM. Odontogenic cysts and neoplasms. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017. March;10(1):177–222. 10.1016/j.path.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Naggar Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg P, editors. WHO classification of Head and Neck Tumours. Chapter 8: Odontogenic and maxilofacial bone tumours. 4th edition, IARC: Lyon 2017, p.205-260.

- 4.Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. WHO Head and Neck Tumours. Chapter 6: Odontogenic tumours. 3rd edition, IARC: Lyon 2005, p. 283-327.

- 5.Kramer IR, Pindborg JJ, Shear M The who histological typing of odontogenic tumours. A commentary on the second edition. Cancer 1992;70(12):2988-2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sweeney RT, McClary AC, Myers BR, Biscocho J, Neahring L, Kwei KA et al. Identification of recurrent SMO and BRAF mutations in ameloblastomas. Nat Genet. 2014. July;46(7):722–5. 10.1038/ng.2986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of central odontogenic tumors: a study of 1,088 cases from Northern California and comparison to studies from other parts of the world. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006. September;64(9):1343–52. 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Takata T. Desmoplastic ameloblastoma (including “hybrid” lesion of ameloblastoma). Biological profile based on 100 cases from the literature and own files. Oral Oncol. 2001. July;37(5):455–60. 10.1016/S1368-8375(00)00111-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Unicystic ameloblastoma. A review of 193 cases from the literature. Oral Oncol. 1998. September;34(5):317–25. 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00012-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dissanayake RK, Jayasooriya PR, Siriwardena DJ, Tilakaratne WM. Review of metastasizing (malignant) ameloblastoma (METAM): pattern of metastasis and treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011. June;111(6):734–41. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Dam SD, Unni KK, Keller EE. Metastasizing (malignant) ameloblastoma: review of a unique histopathologic entity and report of Mayo Clinic experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010. December;68(12):2962–74. 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hertog D, Bloemena E, Aartman IH, van-der-Waal I. Histopathology of ameloblastoma of the jaws; some critical observations based on a 40 years single institution experience. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012. January;17(1):e76–82. 10.4317/medoral.18006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hertog D, van der Waal I. Ameloblastoma of the jaws: a critical reappraisal based on a 40-years single institution experience. Oral Oncol. 2010. January;46(1):61–4. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badni M, Nagaraja A, Kamath V. Squamous odontogenic tumor: A case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012. January;16(1):113–7. 10.4103/0973-029X.92986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones BE, Sarathy AP, Ramos MB, Foss RD. Squamous odontogenic tumor. Head Neck Pathol. 2011. March;5(1):17–9. 10.1007/s12105-010-0198-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: facts and figures. Oral Oncol. 1999. March;35(2):125–31. 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00111-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Siar CH, Ng KH, Lau SH, Zhang X et al. An updated clinical and epidemiological profile of the adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: a collaborative retrospective study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007. August;36(7):383–93. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rick GM. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2004. August;16(3):333–54. 10.1016/j.coms.2004.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy CL, Kestler DP, Foster JS, Wang S, Macy SD, Kennel SJ et al. Odontogenic ameloblast-associated protein nature of the amyloid found in calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumors and unerupted tooth follicles. Amyloid. 2008. June;15(2):89–95. 10.1080/13506120802005965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour: biological profile based on 181 cases from the literature. Oral Oncol. 2000. January;36(1):17–26. 10.1016/S1368-8375(99)00061-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan I, Buchner A, Calderon S, Kaffe I. Radiological and clinical features of calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2001. January;30(1):22–8. 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchner A, Vered M. Ameloblastic fibroma: a stage in the development of a hamartomatous odontoma or a true neoplasm? Critical analysis of 162 previously reported cases plus 10 new cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013. November;116(5):598–606. 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chrcanovic BR, Gomez RS. Ameloblastic fibrodentinoma and ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: an updated systematic review of cases reported in the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017. July;75(7):1425–37. 10.1016/j.joms.2016.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manzon S, Philbert RF, Bush BF, Zola MB, Solomon M. Treatment of a recurrent ameloblastic fibroma. N Y State Dent J. 2015. January;81(1):30–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosqueda-Taylor A, Pires FR, Aguirre-Urízar JM, Carlos-Bregni R, de la Piedra-Garza JM, Martínez-Conde R et al. Primordial odontogenic tumour: clinicopathological analysis of six cases of a previously undescribed entity. Histopathology. 2014. November;65(5):606–12. 10.1111/his.12451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slater LJ, Eftimie LF, Herford AS. Primordial odontogenic tumor: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016. March;74(3):547–51. 10.1016/j.joms.2015.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soluk Tekkesin M, Pehlivan S, Olgac V, Aksakallı N, Alatli C. Clinical and histopathological investigation of odontomas: review of the literature and presentation of 160 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012. June;70(6):1358–61. 10.1016/j.joms.2011.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Praetorius F. Mixed odontogenic tumours and odontomas. Considerations on interrelationship. Review of the literature and presentation of 134 new cases of odontomas. Oral Oncol. 1997. March;33(2):86–99. 10.1016/S0964-1955(96)00067-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchner A, Akrish SJ, Vered M. Central dentinogenic ghost cell tumor: an update on a rare aggressive odontogenic tumor. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016. February;74(2):307–14. 10.1016/j.joms.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Candido GA, Viana KA, Watanabe S, Vencio EF. Peripheral dentinogenic ghost cell tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009. September;108(3):e86–90. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun G, Huang X, Hu Q, Yang X, Tang E. The diagnosis and treatment of dentinogenic ghost cell tumor. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009. November;38(11):1179–83. 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monteiro LS, Martins M, Pacheco JJ, Salazar F, Magalhães J, Vescovi P et al. Er:Yag laser assisted treatment of central odontogenic fibroma of the mandible. Case Rep Dent. 2015;2015:230297. 10.1155/2015/230297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosqueda-Taylor A, Martínez-Mata G, Carlos-Bregni R, Vargas PA, Toral-Rizo V, Cano-Valdéz AM et al. Central odontogenic fibroma: new findings and report of a multicentric collaborative study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011. September;112(3):349–58. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olgac V, Koseoglu BG, Aksakalli N. Odontogenic tumours in Istanbul: 527 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006. October;44(5):386–8. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raubenheimer EJ, Noffke CE. Peripheral odontogenic myxoma: a review of the literature and report of two cases. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2012. March;11(1):101–4. 10.1007/s12663-011-0194-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martínez-Mata G, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Carlos-Bregni R, de Almeida OP, Contreras-Vidaurre E, Vargas PA et al. Odontogenic myxoma: clinico-pathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural findings of a multicentric series. Oral Oncol. 2008. June;44(6):601–7. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noffke CE, Raubenheimer EJ, Chabikuli NJ, Bouckaert MM. Odontogenic myxoma: review of the literature and report of 30 cases from South Africa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007. July;104(1):101–9. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meleti M, Giovannacci I, Corradi D, Manfredi M, Merigo E, Bonanini M et al. Odontogenic myxofibroma: a concise review of the literature with emphasis on the surgical approach. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2015. January;20(1):e1–6. 10.4317/medoral.19842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brannon RB, Fowler CB, Carpenter WM, Corio RL. Cementoblastoma: an innocuous neoplasm? A clinicopathologic study of 44 cases and review of the literature with special emphasis on recurrence. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002. March;93(3):311–20. 10.1067/moe.2002.121993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jelic JS, Loftus MJ, Miller AS, Cleveland DB. Benign cementoblastoma: report of an unusual case and analysis of 14 additional cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993. September;51(9):1033–7. 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80051-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Mofty SK. Fibro-osseous lesions of the craniofacial skeleton: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2014. December;8(4):432–44. 10.1007/s12105-014-0590-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Wang H, You M, Yang Z, Miao J, Shimizutani K et al. Ossifying fibromas of the jaw bone: 20 cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010. January;39(1):57–63. 10.1259/dmfr/96330046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunner P, Bihl M, Jundt G, Baumhoer D, Hoeller S. BRAF p.V600E mutations are not unique to ameloblastoma and are shared by other odontogenic tumors with ameloblastic morphology. Oral Oncol. 2015. October;51(10):e77–8. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall JM, Weathers DR, Unni KK. Ameloblastic carcinoma: an analysis of 14 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007. June;103(6):799–807. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kruse AL, Zwahlen RA, Grätz KW. New classification of maxillary ameloblastic carcinoma based on an evidence-based literature review over the last 60 years. Head Neck Oncol. 2009. August;1(1):31. 10.1186/1758-3284-1-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright JM, Vered M Update from the 4th edition of the world health organization classification of head and neck tumours: Odontogenic and maxillofacial bone tumors. Head Neck Pathol 2017;11(1):68-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas G, Pandey M, Mathew A, Abraham EK, Francis A, Somanathan T et al. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaw: pooled analysis of world literature and report of two new cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001. August;30(4):349–55. 10.1054/ijom.2001.0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zwetyenga N, Pinsolle J, Rivel J, Majoufre-Lefebvre C, Faucher A, Pinsolle V. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaws. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001. July;127(7):794–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tiwari M. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the mandible: A case report with literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011. May;15(2):205–10. 10.4103/0973-029X.84506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bodner L, Manor E, Shear M, van der Waal I. Primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma arising in an odontogenic cyst: a clinicopathologic analysis of 116 reported cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011. November;40(10):733–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koutlas IG, Allen CM, Warnock GR, Manivel JC. Sclerosing odontogenic carcinoma: a previously unreported variant of a locally aggressive odontogenic neoplasm without apparent metastatic potential. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008. November;32(11):1613–9. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31817a8a58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richardson MS, Muller S. Malignant odontogenic tumors: an update on selected tumors. Head Neck Pathol. 2014. December;8(4):411–20. 10.1007/s12105-014-0584-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan SH, Yeo JF, Kheem Pang BN, Petersson F. An intraosseous sclerosing odontogenic tumor predominantly composed of epithelial cells: relation to (so-called) sclerosing odontogenic carcinoma and epithelial-rich central odontogenic fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014. October;118(4):e119–25. 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bilodeau EA, Weinreb I, Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Dacic S, Muller S et al. Clear cell odontogenic carcinomas show EWSR1 rearrangements: a novel finding and a biological link to salivary clear cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013. July;37(7):1001–5. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828a6727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ebert CS Jr, Dubin MG, Hart CF, Chalian AA, Shockley WW. Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma: a comprehensive analysis of treatment strategies. Head Neck. 2005. June;27(6):536–42. 10.1002/hed.20181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Loyola AM, Cardoso SV, de Faria PR, Servato JP, Barbosa de Paulo LF, Eisenberg AL et al. Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma: report of 7 new cases and systematic review of the current knowledge. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015. October;120(4):483–96. 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dahiya S, Kumar R, Sarkar C, Ralte M, Sharma MC. Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma: a diagnostic dilemma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2002;8(4):283–5. 10.1007/BF03036748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ledesma-Montes C, Gorlin RJ, Shear M, Prae Torius F, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Altini M et al. International collaborative study on ghost cell odontogenic tumours: calcifying cystic odontogenic tumour, dentinogenic ghost cell tumour and ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008. May;37(5):302–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00623.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ahmed SK, Watanabe M, deMello DE, Daniels TB. Pediatric metastatic odontogenic ghost cell carcinoma: A multimodal treatment approach. Rare Tumors. 2015. May;7(2):5855. 10.4081/rt.2015.5855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bertoni F, Del Corso G, Bacchini P, Marchetti C, Tarsitano A. Ameloblastic Fibrosarcoma of the mandible evolving from a prior Ameloblastic Fibroma after two years: an unusual finding. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016. October;24(7):656–9. 10.1177/1066896916646448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muller S, Parker DC, Kapadia SB, Budnick SD, Barnes EL. Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma of the jaws. A clinicopathologic and DNA analysis of five cases and review of the literature with discussion of its relationship to ameloblastic fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995. April;79(4):469–77. 10.1016/S1079-2104(05)80130-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kunkel M, Ghalibafian M, Radner H, Reichert TE, Fischer B, Wagner W. Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma or odontogenic carcinosarcoma: a matter of classification? Oral Oncol. 2004. April;40(4):444–9. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim IK, Pae SP, Cho HY, Cho HW, Seo JH, Lee DH et al. Odontogenic carcinosarcoma of the mandible: a case report and review. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015. June;41(3):139–44. 10.5125/jkaoms.2015.41.3.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeLair D, Bejarano PA, Peleg M, El-Mofty SK. Ameloblastic carcinosarcoma of the mandible arising in ameloblastic fibroma: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007. April;103(4):516–20. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]