Abstract

Introduction

Understanding the reasons for fluctuations in teenage driver crashes over time in the United States is clouded by the lack of information on licensure rates and driving exposure.

Methods

We examined results from the Monitoring the Future survey to estimate the proportion of high school seniors who possessed a driver’s license and the proportion of seniors who did not drive “during an average week” during the 15-year period of 1996–2010.

Results

During 1996–2010, the proportion of high school seniors in United States who reported having a driver’s license declined by 12 percentage points (14%) from 85% to 73%. Two-thirds of the decline (8 percentage points) occurred during 2006–2010. During the same 15-year period, the proportion of high school seniors who did not drive during an average week increased by 7 percentage points (47%) from 15% in 1996 to 22% in 2010, with essentially all of the increase occurring during 2006–2009.

Discussion

Findings in this report suggest that the economic recession in recent years has reduced rates of licensure and driving among high school seniors.

Keywords: Adolescent, Teenagers, Motor vehicles, Automobile driving, Licensure

1. Introduction

Understanding the reasons for fluctuations in teenage driver crashes over time in the United States is clouded by the lack of information on licensure rates and driving exposure. The National Household Travel Survey provides extensive data on exposure, but it is conducted only sporadically, the last two times in 2009 and 2001. Licensing data are provided yearly by the Federal Highway Administration. However, these data are not suitable for research purposes, especially for the youngest drivers, because of inconsistencies among states as to who qualifies as a licensed driver, and large, inexplicable year-to-year changes in counts in some states (Foss & Martell, 2013). In view of these limitations, we examined results from the Monitoring the Future survey to estimate the proportion of high school seniors who possessed a driver’s license and the proportion of seniors who did not drive “during an average week” during the 15-year period of 1996–2010.

2. Methods

Since its inception in 1975, the self-administered Monitoring the Future survey has included questions about licensure and driving. In the spring of each year, the survey is administered to approximately 15,000 high school seniors attending approximately 130 public or private schools (Bachman, Johnston, & O’Malley, 2011). The survey uses a multi-stage sampling procedure to produce a representative sample of seniors in the 48 contiguous states. Students are randomly given one of six survey forms. Some of the survey questions are included on all six forms, whereas others are included on only one form. Further details about the survey methods and limitations are available elsewhere (Bachman, Johnston, O’Malley, & Schulenberg, 2006; Bachman et al., 2011; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011).

For 1996–2010, the years included in this report, the survey response rate ranged between 79% and 85%. The licensure question read, “Do you have a driver’s license?” The question was included in only one of six forms, and therefore, responses were based on annual sample sizes of between 2,103 and 2,547. The driving question read, “During an average week, how much do you usually drive a car, truck, or motorcycle?” This question was included on all six questionnaire forms and responses were based on annual sample sizes of between 12,098 and 14,692. The data were accessed from 15 separate reference volumes at http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#refvols. Results reported by race include only students who identified as “Black or African American” or “White (Caucasian).” All other analyses include students of all reported races and ethnicities. Confidence intervals for the proportions presented were estimated using the method described in Appendix A and Table A-1 of the 2010 Monitoring the Future reference volume (Bachman et al., 2011).

3. Results

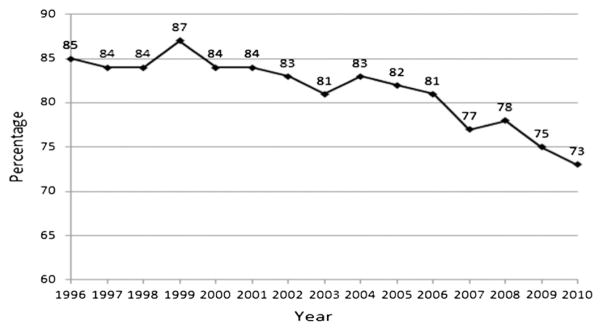

During 1996–2010, the proportion of high school seniors in United States who reported having a driver’s license declined by 12 percentage points (14%) from 85% to 73% (Fig. 1). Two-thirds of the decline (8 percentage points) occurred during 2006–2010. The age distributions of seniors were similar in 1996 and 2010; with 99% of seniors being 17 years or older in both years. Youth in every state and the District of Columbia can be licensed to drive by age 17 (Insurance Institute for Highway Safety [IIHS], 2013).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of U.S. high school seniors who had a driver’s license, Monitoring the Future, 1996–2010.

Licensure varied by both gender and race, with a higher proportion of males licensed compared with females and a higher proportion of whites licensed compared with blacks (Table 1). The proportion of licensed black seniors varied substantially from year to year due to the small sample sizes, which ranged from 210 to 425.

Table 1.

Proportion of U.S. high school seniors who had a driver’s license, by gender and race, Monitoring the Future, 1996–2010.

| Total % (95% CI)* |

Male % (95% CI) |

Female % (95% CI) |

White % (95% CI) |

Black % (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||

| 1996 | 85 (83, 87) | 91 (88, 93) | 80 (77, 83) | 92 (90, 94) | 74 (67, 80) |

| 1997 | 84 (82, 86) | 88 (86, 90) | 81 (78, 84) | 92 (90, 94) | 65 (58, 71) |

| 1998 | 84 (82, 86) | 88 (85, 90) | 81 (79, 84) | 92 (90, 94) | 66 (59, 72) |

| 1999 | 87 (85, 89) | 92 (89, 94) | 84 (81, 86) | 92 (90, 94) | 74 (66, 82) |

| 2000 | 84 (81, 85) | 87 (84, 89) | 80 (77, 83) | 90 (88, 92) | 66 (59, 72) |

| 2001 | 84 (82, 86) | 90 (87, 92) | 79 (76, 82) | 91 (89, 93) | 73 (66, 79) |

| 2002 | 83 (81, 85) | 88 (85, 90) | 79 (76, 82) | 91 (89, 92) | 57 (49, 66) |

| 2003 | 81 (79, 83) | 84 (81, 86) | 78 (75, 81) | 89 (87, 90) | 65 (56, 72) |

| 2004 | 83 (81, 85) | 87 (84, 90) | 79 (76, 82) | 90 (88, 92) | 66 (57, 73) |

| 2005 | 82 (80, 84) | 86 (83, 88) | 79 (76, 82) | 90 (88, 92) | 59 (50, 68) |

| 2006 | 81 (78, 83) | 85 (82, 87) | 77 (74, 79) | 89 (87, 90) | 68 (59, 75) |

| 2007 | 77 (75, 80) | 82 (78, 84) | 74 (70, 77) | 86 (84, 89) | 60 (52, 68) |

| 2008 | 78 (76, 80) | 83 (80, 86) | 74 (70, 77) | 88 (86, 90) | 57 (50, 64) |

| 2009 | 75 (72, 77) | 80 (77, 83) | 70 (66, 73) | 84 (82, 86) | 65 (56, 72) |

| 2010 | 73 (71, 75) | 78 (75, 81) | 68 (65, 72) | 84 (82, 86) | 61 (54, 67) |

95% CI: confidence interval.

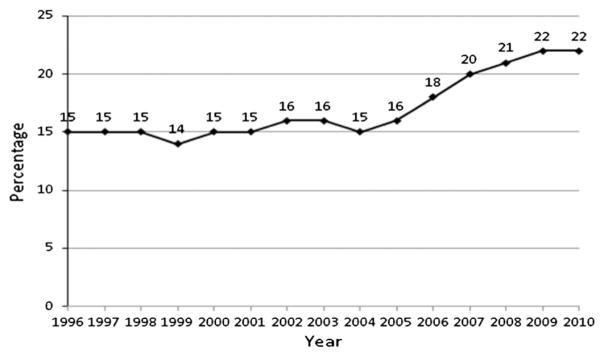

During the same 15-year period, the proportion of high school seniors who did not drive during an average week increased by 7 percentage points (47%) from 15% in 1996 to 22% in 2010 (Fig. 2). The proportion who did not drive was essentially stable during 1996–2005, and then climbed during 2006–2009.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of U.S. high school seniors who did not drive during an average week, Monitoring the Future, 1996–2010.

As with licensure, the proportion of seniors who reported not driving varied by gender and race, with a higher proportion of females not driving compared with males and a higher proportion of blacks not driving compared with whites (Table 2). In 2010, 1 in 4 female seniors and 1 in 3 black seniors did not drive during an average week.

Table 2.

Proportion of U.S. high school seniors who did not drive during an average week, by gender and race, Monitoring the Future, 1996–2010.

| Total % (95% CI)* |

Male % (95% CI) |

Female % (95% CI) |

White % (95% CI) |

Black % (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||

| 1996 | 15 (14, 16) | 12 (11, 13) | 17 (16, 19) | 9 (8, 10) | 28 (24, 32) |

| 1997 | 15 (14, 16) | 12 (11, 13) | 17 (16, 19) | 9 (8, 10) | 28 (24, 31) |

| 1998 | 15 (14, 16) | 12 (11, 13) | 18 (16, 19) | 8 (8, 9) | 33 (29, 36) |

| 1999 | 14 (13, 16) | 10 (9, 11) | 18 (17, 20) | 9 (8, 10) | 32 (28, 35) |

| 2000 | 15 (14, 16) | 11 (10, 13) | 18 (17, 20) | 10 (9, 11) | 27 (24, 31) |

| 2001 | 15 (14, 16) | 10 (9, 12) | 19 (18, 21) | 9 (8, 11) | 28 (25, 32) |

| 2002 | 16 (15, 17) | 12 (11, 14) | 19 (18, 21) | 9 (8, 10) | 37 (33, 41) |

| 2003 | 16 (15, 17) | 14 (13, 15) | 18 (16, 19) | 10 (9, 11) | 29 (25, 33) |

| 2004 | 15 (14, 16) | 12 (11, 13) | 17 (16, 18) | 10 (9, 11) | 30 (26, 34) |

| 2005 | 16 (15, 18) | 14 (12, 15) | 19 (18, 20) | 9 (8, 10) | 36 (32, 40) |

| 2006 | 18 (16, 19) | 15 (13, 16) | 20 (19, 22) | 11 (10, 12) | 30 (26, 33) |

| 2007 | 20 (19, 22) | 17 (15, 18) | 23 (22, 25) | 12 (11, 13) | 37 (34, 41) |

| 2008 | 21 (20, 22) | 17 (16, 19) | 24 (23, 26) | 13 (11, 14) | 36 (32, 39) |

| 2009 | 22 (20, 23) | 18 (16, 19) | 25 (24, 26) | 14 (12, 15) | 34 (30, 39) |

| 2010 | 22 (21, 24) | 18 (17, 20) | 26 (24, 28) | 14 (13, 15) | 37 (33, 41) |

95% CI: confidence interval.

4. Conclusions and Comment

Findings from the Monitoring the Future survey confirm the widely held belief that licensure rates among teenagers have declined over time. The results also suggest that fewer high school seniors are routinely driving, and that meaningful differences exist by gender and race in both licensure rates and driving. Much of the decline in licensing and driving has occurred since 2006, which coincides with the sharp decreases in driver deaths among 17–19-year-olds that occurred during the 2007–2010 period (Governors Highway Safety Association, 2013). It has been suggested that declines in teen licensure may be due to lesser interest because teens can connect with each other electronically (Sivak & Schoettle, 2012), and that some teens might be waiting until they reach age 18 to avoid graduated driver licensing requirements (Masten, Foss, & Marshall, 2011). However, contemporary surveys of teenagers indicate that the main reasons given for delaying licensure are the economic costs of licensure and driving (Williams, 2011; Williams & Tefft, 2013). The current report further suggests that the economic recession in recent years has reduced rates of licensure and driving among high school seniors. As the economy continues to recover, data from Monitoring the Future will help to confirm or refute this hypothesis.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

The Journal of Safety Research has partnered with the Office of the Associate Director for Science, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention in the National Center for Injury Prevention & Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, to briefly report on some of the latest findings in the research community. This report is the 30th in a series of CDC articles.

References

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE. The Monitoring the Future project after thirty-two years: Design and procedures (Occasional Paper No. 64) Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the Future: Questionnaire responses from the nation’s high school seniors, 2010. 2011 ([cited 2013 March 20]. Available from: http://monitoringthefuture.org/datavolumes/2010/2010dv.pdf)

- Foss RD, Martell C. Did graduated driver licensing increase the number of newly licensed 18-year-old drivers in North Carolina. Presentation to the Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting; Washington DC. January 15 2013; 2013. ([cited 2013 March 20]. Available from: http://www.youngdriversafety.org/docs/2013/Foss2.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Governors Highway Safety Association. Teenage driver fatalities by state; 2012 preliminary data. Washington DC: 2013. ([cited 2013 March 20]. Available from: http://www.ghsa.org/html/publications/pdf/spotlights/spotlight_teens12.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Young drivers licensing systems in the U.S. 2013 Feb; [cited 2013 March 20]. Available from: http://www.iihs.org/laws/GraduatedLicenseCompare.aspx.

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010. 2011:63–80. Volume 1: Secondary school students. ([cited 2013 March 20]. Available from: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2010.pdf)

- Masten SV, Foss RD, Marshall S. Graduated driver licensing and fatal crashes involving 16- to 19-year-old drivers. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306:1099–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivak M, Schoettle B. Recent changes in the age composition of drivers in 15 countries. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2012;13:126–132. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.638016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AF. Teenagers licensing decisions and their views of licensing policies: a national survey. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2011;12:312–319. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.572100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AF, Tefft BC. Delayed licensure and reasons for delay among 18–20-year-olds. Presentation to the Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting; Washington DC. January 15, 2013; 2013. ([cited 2013 March 20]. Available from: http://www.youngdriversafety.org/docs/2013/Tefft.pdf) [Google Scholar]