Summary

The relationship between recruitment of mononuclear phagocytes to lymphoid and gut tissues and disease in HIV and SIV infection remains unclear. To address this question, we did cross-sectional analyses of dendritic cell (DC) subsets and CD163+ macrophages in lymph nodes (LNs) and ileum of rhesus macaques with acute and chronic SIV infection and AIDS. In LNs significant differences were only evident when comparing uninfected and AIDS groups, with loss of myeloid DCs and CD103+ DCs from peripheral and mesenteric LNs, respectively, and accumulation of plasmacytoid DCs and macrophages in mesenteric LNs. In contrast, there were 4-fold more macrophages in ileum lamina propria in macaques with AIDS compared to chronic infection, and this increased to 40-fold in Peyer’s patches. Gut macrophages exceeded plasmacytoid DCs and CD103+ DCs by 10- to 17-fold in monkeys with AIDS but were at similar low frequencies as DCs in chronic infection. Gut macrophages in macaques with AIDS expressed IFN-α and TNF-α consistent with cell activation. CD163+ macrophages also accumulated in gut mucosa in acute infection but lacked expression of IFN-α and TNF-α. These data reveal a relationship between inflammatory macrophage accumulation in gut mucosa and disease and suggest a role for macrophages in AIDS pathogenesis.

Keywords: AIDS, nonhuman primate, lymphoid tissue, mononuclear phagocytes, gut macrophages

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages are mononuclear phagocytes that bridge innate and adaptive immunity while also contributing to pathogen control and inflammation. In HIV infection of humans and SIV infection of Asian macaques, a loss of the two major DC subsets, myeloid DCs (mDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), from blood is negatively correlated with viral load and disease outcome [1-9]. This loss is driven by apoptosis and by recruitment of DCs to lymph nodes (LNs) and gut mucosa, coincident with altered function and production of inflammatory cytokines [9-18]. Chronic SIV infection of rhesus macaques is also associated with loss from intestinal mucosa of CD103+ DCs [19], an important DC subset that traffics from gut to mesenteric LNs and imprints gut homing on lymphocytes [20-22]. Loss of CD103+ DCs is thought to contribute to loss of IL-17-producing lymphocytes from gut and damage to gastrointestinal mucosal integrity [19], factors that lead to microbial translocation [23, 24]. Collectively these findings have led to a focus on DCs as potential contributors of immune activation that is a hallmark of AIDS [25-27].

Much less is understood about the mobilization and trafficking of macrophages in HIV and SIV infection and the potential contribution of macrophages to disease control or progression [28, 29]. Macrophages accumulate in inguinal and axillary LNs during acute SIV infection of rhesus macaques [18, 30], and increased monocyte turnover is correlated with progression to AIDS in this model [31, 32]. Macrophages are most abundant in health in intestinal tissues [33], and further accumulation of macrophages in the intestine is seen in untreated HIV infection of humans and SIV infection of rhesus macaques [34, 35]. Evidence also exists for intestinal production of macrophage-associated proinflammatory molecules and altered macrophage phagocytic function and responsiveness to LPS in HIV and SIV infection [34, 35]. However, whether alteration in macrophage dynamics in SIV or HIV infection is beneficial or detrimental remains an open question, as there have been no studies to our knowledge evaluating macrophage dynamics across different stages of infection and disease.

To address these gaps in our understanding, in this study we determined the frequency and turnover of macrophages and DC subsets in LNs and gut mucosa of rhesus macaques with acute and chronic SIV infection and AIDS. Our data reveal relatively modest differences between cell types in LNs in macaques with AIDS only when compared to uninfected animals. In contrast, up to 40-fold more macrophages were present in intestinal mucosa in macaques with acute SIV infection and AIDS relative to macaques with chronic SIV infection lacking disease. Gut macrophages from animals with AIDS but not acute infection have evidence of an inflammatory function, consistent with a role in disease progression.

Results

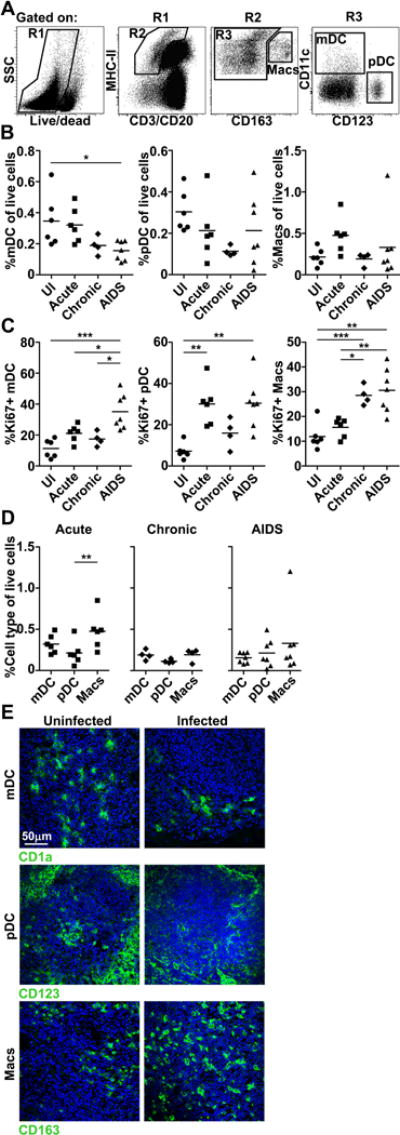

mDC loss and marked increases in cell turnover in peripheral LNs in macaques with AIDS

To evaluate the impact of pathogenic SIV infection on macrophages and DC subsets in lymphoid and mucosal tissues we did cross-sectional analyses using specimens from rhesus macaques infected with the biologic isolate SIVmac251 as part of previous studies [9, 11, 36]. Tissues were harvested either at the acute stage of infection (wk 2, n=6), at the chronic stage of infection but without disease (range wk 66 to 78, median wk 71, n=6), or from animals with rapid progression to AIDS (range wk 11 to 43, median wk 33, n=8) (Table 1). Samples from SIV–infected macaques were compared to healthy SIV-naïve macaques (n=8). We first analyzed mononuclear phagocytes in cell suspensions of inguinal, axillary or popliteal LNs, which we collectively termed peripheral LNs. To delineate mononuclear phagocytes we used established flow cytometry methods [18] gating on CD3/CD20(lineage)−MHC-II+CD163−CD11c+CD123− cells for mDCs, lineage−MHC-II+CD163−CD11c−CD123+ cells for pDCs, and lineage−MHC-II+CD163+ cells for macrophages (Fig. 1A). To determine changes in individual subsets independently, the frequency of DCs and macrophages was calculated as a proportion of all live cells, which was based on lack of fluorescence after exposure to an amine-reactive dye (Fig. 1A). Preliminary findings using peripheral LN samples from macaques with acute (wk 2, n=6) and chronic (wk 20, n=11) SIVmac251 infection showed that mDC, pDC and macrophage frequencies determined in this manner are highly correlated to frequencies based on tissue weight (R=0.8589, P<0.0001; data not shown), indicating that changes in T and B lymphocytes over time do not erroneously affect DC and macrophage frequencies when based on total number of live cells. In peripheral LNs only the frequency of mDCs differed significantly across conditions, with loss of mDCs in monkeys with AIDS relative to uninfected macaques. There was a trend towards loss of pDCs in chronic infection and an increase in macrophages in acute infection (Fig. 1B). SIV infection was associated with marked differences in the proportion of each subset expressing Ki67, a marker of recent cell division [11]. The proportion of Ki67+ mDCs in peripheral LNs of monkeys with AIDS exceeded all other groups, and Ki67+ pDCs in monkeys with AIDS and acute infection were greater than uninfected macaques. The frequency of Ki67+ macrophages in peripheral LNs in chronic infection and AIDS was greater than that in uninfected and acutely infected macaques (Fig. 1C). When comparing the frequency of each cell type at different stages of infection or disease, the proportion of macrophages exceeded mDCs in acute infection only (Fig. 1D). Flow cytometry findings were supported by immunohistochemistry analysis showing evidence of a loss of mDCs and pDCs in chronically infected relative to uninfected tissues, and a relative abundance of macrophages in acute infection (Fig. 1E).

Table 1.

Animal characteristics

| Animal | Time post infection (wk) |

Plasma virus load (RNA copies/mL) |

Blood CD4 T cells (cells/μL) |

Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M182-06 | 2 | 2,340,000 | 272 | Acute | [11] |

| M183-06 | 2 | 8,120,000 | 773 | Acute | [11] |

| M184-06 | 2 | 4,470,000 | 584 | Acute | [11] |

| M185-06 | 2 | 9,410,000 | 730 | Acute | [11] |

| M186-06 | 2 | 104,000 | 600 | Acute | [11] |

| M187-06 | 2 | 3,580,000 | 645 | Acute | [11] |

| R479 | 66 | 81,200a | 360 | Chronic | [9] |

| R486 | 67 | 490a | 924 | Chronic | [9] |

| M135-08 | 67 | 2,108 | 144b | Chronic | [36] |

| M138-08 | 75 | 51,928 | 66c | Chronic | [36] |

| M9010 | 75 | 425 | 294c | Chronic | [36] |

| M131-08 | 78 | 26,386 | 238c | Chronic | [36] |

| R189 | 11 | 44,000,000 | 823d | AIDS | [9] |

| R488 | 18 | 27,000,000 | 1,249 | AIDS | [9] |

| R482 | 27 | 1,210,000 | 1,164 | AIDS | [9] |

| R477 | 32 | 14,900,000 | 592 | AIDS | [9] |

| R485 | 33 | 2,330,000 | 317 | AIDS | [9] |

| M5206 | 36 | 8,730,000 | 384 | AIDS | [9] |

| R180 | 43 | 4,460,000 | 255 | AIDS | [9] |

| R183 | 43 | 151,000 | 361 | AIDS | [9] |

wk 58,

wk 62,

wk 70,

wk 8

Figure 1. mDCs are lost from peripheral LNs in macaques with AIDS.

(A) Representative flow cytometric analysis of peripheral LN single-cell suspensions showing gating strategy to define macrophages (Macs), mDCs, and pDCs after exclusion of dead cells by amine reactive dye labeling. (B, C) The proportion of each mononuclear phagocyte population in the live cell fraction (B) and the proportion of each population expressing Ki67 (C) in peripheral LNs from uninfected (UI) macaques and macaques with acute and chronic SIV infection and AIDS. (D) The proportion of cells in the live cell fraction of peripheral LNs that is mDCs, pDCs or macrophages in acute and chronic SIV infection or AIDS. (B-D) Each symbol represents an individual animal and horizontal bars represent means. * P<.05; ** P<.01; *** P<.001. Statistical comparisons were done using (B, C) ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test or (D) repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s range test. (A-D) Data shown represent 11 independent experiments. (E) Immunofluorescence of peripheral LN sections from uninfected (left) and SIV-infected (right) macaques labeled with antibody to CD1a, CD123 and CD163 to identify mDCs, pDCs and macrophages, respectively. SIV-infected sections were taken at chronic infection for mDCs, and at acute infection for pDCs and macrophages. Blue staining in each section are nuclei labeled with Hoechst dye. Original magnification = 400×. Images shown are representative of 5 independent experiments.

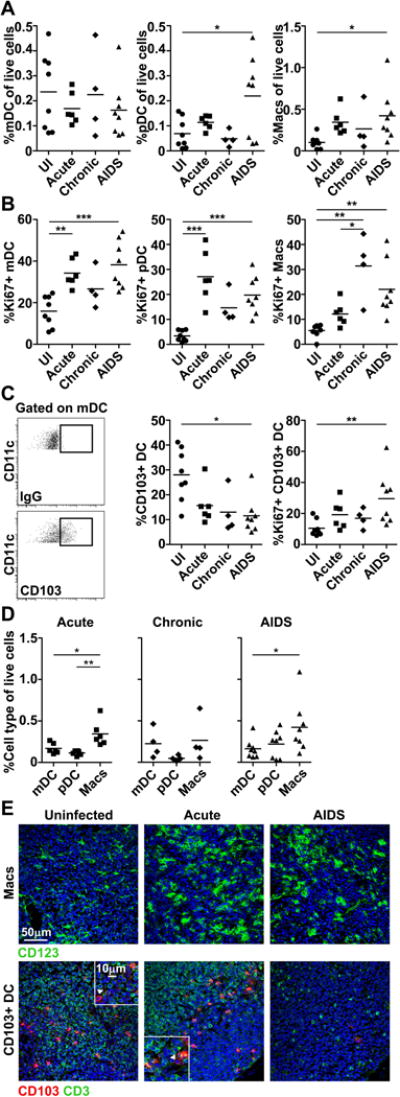

pDCs and macrophages accumulate but CD103+ DCs are depleted in mesenteric LNs in monkeys with AIDS

We next investigated the influence of SIV infection on DC and macrophage dynamics in mesenteric LNs that drain the gut mucosa using similar strategies. In contrast to peripheral LNs, there was no change in the frequency of mDCs over the course of infection, whereas pDCs and macrophages both significantly increased in frequency in monkeys with AIDS relative to uninfected monkeys (Fig. 2A). The frequency of Ki67+ mDCs and pDCs both increased significantly in acute infection and in AIDS, whereas the frequency of Ki67+ macrophages increased in chronic infection and AIDS (Fig. 2B). We next evaluated CD103+ DCs, which were identified as a subset of CD11c+ mDCs. CD103+ DCs constituted about 30% of mDCs prior to infection in mesenteric LNs but were absent from peripheral LNs (Fig. 2C and data not shown). CD103+ DCs were lost from mesenteric LNs and the frequency of Ki67+ CD103+ DCs was significantly increased in AIDS relative to uninfected animals (Fig. 2C). The frequency of macrophages exceeded mDCs (with the CD103+ subset included) in acute infection and in AIDS, and exceeded pDCs in acute infection, but similar frequencies of each cell type were present in mesenteric LNs in chronic infection (Fig. 2D). To support the flow cytometry findings we did immunohistochemistry of mesenteric LNs focusing on macrophages and CD103+ DCs, which were distinguished from T cells by lack of CD3 staining. As expected in situ staining revealed an increase in macrophages but a marked loss of CD103+ DCs as infection progressed (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2. Loss of CD103+ DCs but accumulation of pDCs and macrophages in mesenteric LNs in macaques with AIDS.

(A, B) The proportion of each mononuclear phagocyte in the live cell fraction (A) and the proportion of each population expressing Ki67 (B) in mesenteric LNs from uninfected (UI) macaques and macaques with acute and chronic SIV infection and AIDS. (C) (Left) Representative flow cytometric analysis of mesenteric LN single-cell suspensions showing gating to define the CD103+ fraction of mDC based on isotype control antibody (IgG) labeling. (Right) The proportion of mDC that is CD103+ and the proportion of these cells that express Ki67 in mesenteric LNs from uninfected (UI) macaques and macaques with acute and chronic SIV infection or AIDS. (D) The proportion of cells in the live cell fraction of mesenteric LNs that is mDCs, pDCs or macrophages (Macs) in acute and chronic SIV infection or AIDS. (A-D) Each symbol represents an individual animal and horizontal bars represent means. * P<.05; ** P<.01; *** P<.001. Statistical comparisons were done using (A-C) ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test or (D) repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s range test. Data shown represent 14 independent experiments. (E) Immunofluorescence of mesenteric LN sections from uninfected macaques and macaques with acute SIV infection or AIDS labeled with antibody to CD163 to identify macrophages and CD3 and CD103 to identify CD103+CD3− DC (highlighted by arrowheads). Blue staining in each section are nuclei labeled with Hoechst dye. Original magnification = 400×. Images shown are representative of 5 independent experiments.

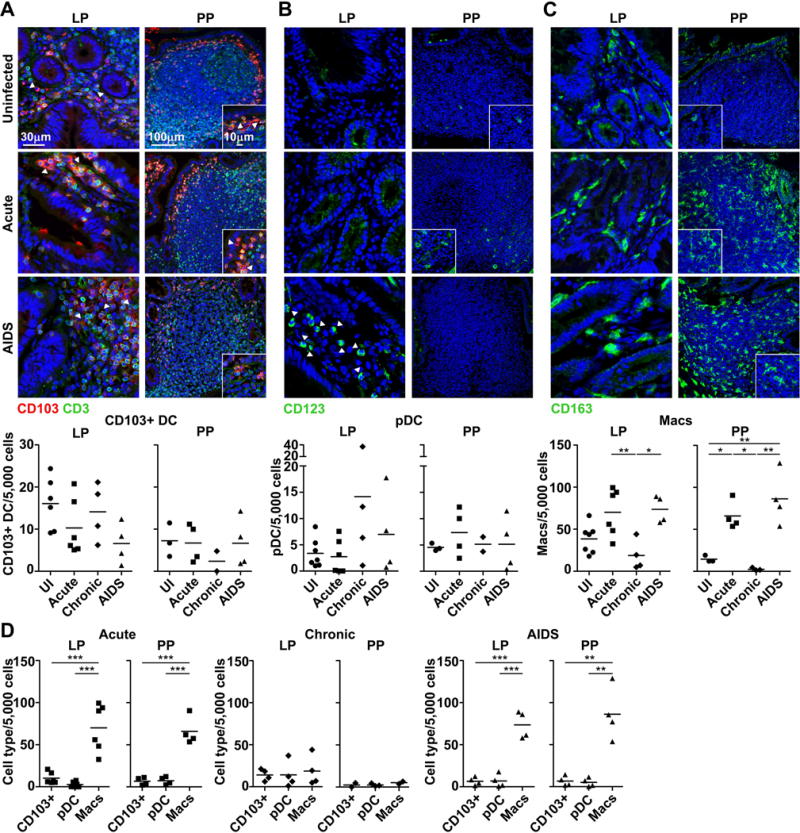

Macrophages accumulate in gut mucosa in acute SIV infection and AIDS but not chronic infection

Next we used immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy to detect mononuclear phagocytes in the ileum in a subset of macaques for which tissues were available. We chose to image and quantify cells in situ to provide information on the local distribution within Peyer’s patches (an immune inductive site) and lamina propria (an immune effector site) and to avoid prolonged tissue processing associated with generation of cell suspensions which may lead to unintended cell loss. For mDCs we focused on the CD103+ subset given the profound loss from mesenteric LNs. CD103+ DCs in naïve macaques were primarily found in the subepithelial dome and T cell rich interfollicular zones of Peyer’s patches and scattered throughout the lamina propria, and there was a trend towards loss of CD103+ DCs from lamina propria in monkeys with AIDS (Fig. 3A). CD123+ pDCs were infrequent in both lamina propria and Peyer’s patches of uninfected ileum and there was a non-significant trend to accumulation of pDCs in lamina propria in chronic infection and AIDS associated with considerable animal-to-animal variation (Fig. 3B). CD163+ macrophages were present at high frequencies relative to CD103+ DCs and pDCs prior to infection, most notably in lamina propria (Fig. 3C). In marked contrast to DCs, the frequency of macrophages in gut mucosa differed significantly as a function of stage of infection and disease status. Monkeys with acute infection and AIDS had significantly greater frequencies of macrophages in both lamina propria and Peyer’s patches than did monkeys with chronic infection lacking disease (Fig. 3C). The frequency of macrophages in these compartments was 10 to 20 times higher than CD103+ DCs and pDCs in acute infection and AIDS but did not differ from the DC subsets in chronically infected tissues (Fig. 3D). The frequency of macrophages in gut mucosa did not correlate with peripheral CD4+ T cell counts or plasma virus load (data not shown).

Figure 3. Accumulation of macrophages in gut mucosa in macaques with acute SIV infection and AIDS but not chronic infection.

(A-C) (Top) Immunofluorescence of ileum sections from uninfected macaques and macaques with acute SIV infection and AIDS stained with antibodies to CD103 and CD3 to identify CD103+CD3− DC (A), CD123 to identify pDC (B) and CD163 to identify macrophages (Macs) (C) in lamina propria (LP) and Peyer’s patches (PP). Arrowheads highlight cells of interest. Blue staining in each section are nuclei labeled with Hoechst dye. Original magnification = 200×. Images shown are representative of 12 independent experiments. (Bottom) The frequency of each cell type per 5,000 nucleated cells enumerated using ImageJ and MetaMorph software. (D) The proportion of cells in lamina propria and Peyer’s patches that is CD103+CD3− DC, pDC or macrophages in acute and chronic SIV infection or AIDS. (A-D) Each symbol represents an individual animal and horizontal bars represent means. The number of animals differs between lamina propria and Peyer’s patches as in some cases Peyer’s patches were not identified. * P<.05; ** P<.01; *** P<.001. Statistical comparisons were done using (A-C) ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test or (D) repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s range test.

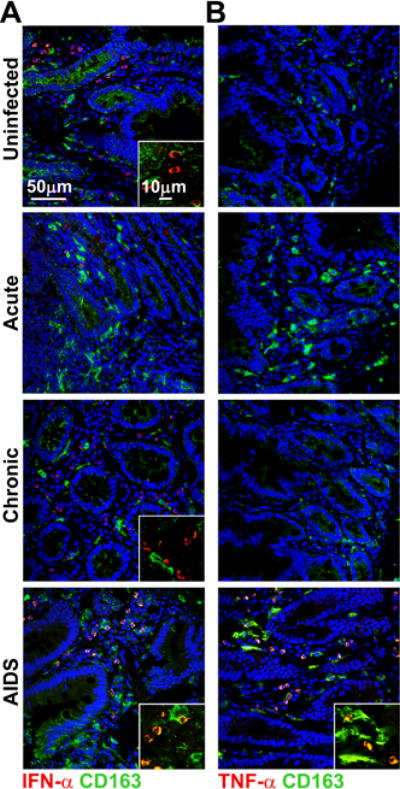

Evidence for inflammatory macrophages in gut mucosa of monkeys with AIDS

To address whether the macrophages that accumulate in gut mucosa in acute infection and AIDS may contribute to the inflammatory response we did in situ staining for CD163 along with pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-α and TNF-α. In both uninfected and chronically infected tissues small numbers of cells expressing IFN-α but not TNF-α were detected, but in both cases cytokine staining did not localize with macrophages. Negligible staining for either cytokine was detected in acutely infected tissues, despite macrophage accumulation (Fig. 4). In contrast, a substantial number of macrophages present in gut mucosa of macaques with AIDS expressed IFN-α and TNF-α, consistent with an inflammatory function, and expression of these cytokines appeared to be restricted to macrophages (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Gut macrophages from macaques with AIDS but not acute infection express IFN-α and TNF-α.

(A, B) Representative immunofluorescence of ileum sections from uninfected macaques and macaques with acute and chronic SIV infection and AIDS labeled with antibody to CD163 to identify macrophages and antibody to IFN-α (A) and TNF-α (B). Blue staining in each section are nuclei labeled with Hoechst dye. Original magnification = 400×. Images shown are representative of 12 independent experiments.

Discussion

This is the first report to our knowledge to provide a detailed comparative analysis of mononuclear phagocyte subsets in lymphoid and mucosal tissues across different stages of SIV infection and disease. Significant differences existed between DCs and macrophages in peripheral and mesenteric LNs when comparing uninfected macaques and macaques with AIDS, consistent with earlier reports [10, 37]. However, only the frequency of macrophages in gut mucosa distinguished macaques with AIDS from those with chronic SIV infection lacking disease. Even with the relatively small number of animals studied this effect was striking, with a 4-fold difference in mean macrophage frequency in lamina propria and a 40-fold difference in mean macrophage frequency in Peyer’s patches of macaques with AIDS compared to chronic infection. These data indicate that accumulation of macrophages in gut mucosa correlates with disease and suggest a role for macrophages in AIDS pathogenesis.

Macrophages are abundant in intestinal mucosa in health and are important in maintaining a non-inflammatory environment and normal tissue homeostasis [33, 38]. In contrast, our findings indicate that CD163+ macrophages accumulating in the gut of macaques with AIDS express TNF-α and IFN-α, consistent with an inflammatory function, and data from untreated HIV-infected patients reveal secretion of a number of macrophage-related proinflammatory molecules in gut mucosa [35]. Similarly, in inflammatory bowel disease and ulcerative colitis, activated macrophages producing proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α infiltrate the bowel and contribute to an inappropriate innate response [39-41]. Macrophage production of TNF-α may directly affect the integrity of gut epithelium by inducing epithelial cell apoptosis and disrupting intercellular tight junctions [42, 43], and gut macrophages in HIV infected-individuals have reduced capacity to phagocytose bacteria that may transit the damaged epithelium [35]. Collectively these findings suggest a potential contribution of macrophages to gut inflammation and microbial translocation in AIDS.

It is notable that CD163+ macrophages also accumulated in gut mucosa in acutely infected macaques but lacked production of IFN-α and TNF-α, suggesting they may be functionally distinct from gut macrophages in AIDS. A key function of macrophages is antigen presentation, and CD163+ macrophages in SIV-infected LNs lose capacity to stimulate CD4+ T cells [44]. It will be important to assess antigen-presenting function of gut macrophages at different stages of SIV infection, particularly as they accumulate heavily in Peyer’s patches, an immune inductive site.

Previous studies have revealed loss of CD103+ DCs from both gut mucosa and mesenteric LNs in rhesus macaques infected with SIV for more than 90 days, although distinction was not made between animals with and without disease [19]. In our study with similar numbers of animals we found significant depletion of CD103+ DCs from mesenteric LNs in macaques with AIDS but not chronic SIV infection relative to uninfected macaques, suggesting that CD103+ DC depletion is a function of disease. CD103+ DCs that migrate from gut mucosa to mesenteric LNs produce retinoic acid from dietary vitamin A that in turn drives development and maintenance of IL-17- and IL-22-producing cells and Treg [22, 45, 46]. IL-17 is associated with maintenance of epithelial integrity, and loss of Th17 cells in acute pathogenic SIV infection correlates with mucosal immune dysfunction and is predictive of systemic immune activation [47, 48]. There is also evidence that Treg are depleted from intestinal lamina propria but not blood or LNs in acute SIV infection [49]. The loss of CD103+ DCs from mesenteric LNs could therefore indirectly impact chronic immune activation and together with macrophage accumulation in gut mucosa could promote microbial translocation through Th17-mediated loss of epithelial integrity.

Accumulation of pDCs in colorectum and ileum of macaques with chronic SIV infection has been noted previously, with frequencies roughly 4-fold greater than in uninfected samples, although there was no comparison done between animals with chronic infection and AIDS [13, 15]. In our study there was a trend towards increased frequency of pDCs in lamina propria of macaques with chronic infection relative to uninfected animals, but no detectable differences in pDC frequency when comparing chronic infection and AIDS. Moreover, macrophages were 10-fold more numerous in lamina propria and 17-fold more numerous in Peyer’s patches in AIDS monkeys compared to pDCs, whereas the frequency of both pDCs and macrophages was low and indistinguishable in chronic infection, reflecting a far greater accumulation of gut macrophages than pDCs in disease.

Both DCs and macrophages appear to have dysregulation of pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules that favors apoptosis in SIV and HIV infection [50], and apoptotic DCs and macrophages can readily be identified in LNs of SIV-infected macaques [10-12, 32]. Despite relatively minor changes in frequency of mononuclear phagocytes in LNs over the course of infection our findings reveal an underlying strong regenerative response with marked increases in Ki67 expression, consistent with previous findings of BrdU incorporation in vivo [11, 18, 32]. These data suggest an increase in cell turnover within LNs, with increased death of cells being offset by increased recruitment of DCs and monocytes from blood.

Our study showed distinct production of IFN-α in gut mucosa in uninfected animals that may serve to protect the mucosa from viral invasion. The source of IFN-α remains to be determined, but constitutive expression of other type I IFN including IFN-ε by intestinal epithelial cells is known to occur in gut mucosa of SIV-naïve macaques [51]. Our findings provide further support for the notion that pDCs are not the exclusive producers of IFN-α in tissues during SIV and HIV infection, and that other cells including macrophages, lymphocytes, and mDCs can contribute significantly to this response [36, 52]. The data suggest that focus should be directed towards macrophages and their potential contribution to the inflammatory response associated with chronic immune activation during AIDS, particularly in the gut mucosal environment.

Materials and methods

Animals and tissues

Indian-origin rhesus macaques housed at the University of Pittsburgh (US Public Health Service Assurance Number: A3187-01) were used in this study and all animal manipulations and procedures were done with appropriate institutional regulatory oversight and approval. Macaques were infected with SIVmac251 as part of previously published studies [9, 11, 36]. Tissues were harvested either at the acute stage (wk 2, n=6) or chronic stage of infection (range wk 66 to 78, median wk 71, n=6), or during AIDS (range wk 11 to 43, median wk 33, n=8) (Table 1). Samples from 8 uninfected, healthy macaques were used as controls. Not all animals were used in all analyses depending on availability of tissues. To generate LN suspensions, freshly harvested LNs were digested using 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 μg/ml DNAse I (Roche) in RPMI 1640 medium with 2% FBS and 10 mmol HEPES and cryopreserved for later use. To generate tissue sections for immunohistochemistry, harvested tissues were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at 4°C and then infused with 30% sucrose overnight. Tissues were frozen with an aerosol of chlorodifluoromethane (Histofreeze 22; Fisher Scientific).

Flow cytometry

LN single-cell suspensions were stained with the following cross-reactive surface-labeling anti-human antibodies for mononuclear phagocyte detection (all antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences unless otherwise noted): CD11c (clone S-HCL-3), CD123 (7G3), CD103 (2G5, Beckman Coulter), CD163 (GH1/61, BioLegend), HLA-DR (L243), CD20 (2H7, eBioscience), and CD3 (SP34-2). Nonviable cells were excluded by staining with a fluorescent LIVE/DEAD cell stain (Invitrogen). For analysis of nuclear protein Ki67 (B56), LN cells were permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and then stained with antibody in Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences). Data were acquired using a LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo 7.6.4.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

LN and ileum sections were hydrated in PBS on Superfrost Plus glass slides and then blocked for 1 h with 10% serum matching the species of the secondary antibody. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched using 0.15% hydrogen peroxide. Sections were incubated for 1.5 h with antibodies to CD163 (GH1/61, eBioscience), CD123 (7G3), CD1a (SK9, BioLegend), CD3 (polyclonal, DAKO) and/or CD103 (2G5.1, AbD Serotec). The remaining steps were conducted in accordance with the standard tyramide signal amplification kit protocol (Invitrogen). To detect cytokine expression, sections were incubated with antibody to IFN-α (MMHA2, PBL Interferon Source) or TNF-α (MAb11) overnight and developed using goat anti-mouse-HRP AlexaFluor 546 with tyramide amplification. Sections were co-stained using biotinylated mouse antibody to CD163 followed by mouse HRP-streptavidin AlexaFluor 488. All staining included an appropriately concentrated isotype-matched antibody. Cell nuclei were identified using membrane permeable Hoescht dye. Slides were mounted in gelvatol mounting medium and viewed on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope. For quantification of cells in gut mucosa, an average of 7 non-overlapping regions of lamina propria and at least 3 entire Peyer’s patches were imaged. Cells of interest were enumerated manually using ImageJ software (US National Institutes of Health) and the total number of nuclei per image was determined digitally using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). Cell frequencies were then calculated using the formula: (total number of cells of interest ×5,000)/total number of nuclei.

Statistical analysis

Cross-sectional comparisons between uninfected and infected groups were performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Comparisons made between cell types within the same animal were done using repeated-measures ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s range test. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amanda P. Smith for technical assistance, Anthea L. Bouwer for helpful discussions, Todd A. Reinhart and Michael Murphey-Corb for providing tissue samples, and Simon C. Watkins and the Center for Biologic Imaging of the University of Pittsburgh for access to confocal microscopes and image analysis tools. This work was funded by US National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI071777 to SMBB and 1S10OD019973 to the Center for Biologic Imaging. ZDS was supported by US National Institutes of Health training grant T32 AI065380 and ERW was supported by National Cancer Institute training grant T32 CA082084.

Abbreviations

- mDC

myeloid DC

- pDC

plasmacytoid DC

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Barron MA, Blyveis N, Palmer BE, MaWhinney S, Wilson CC. Influence of plasma viremia on defects in number and immunophenotype of blood dendritic cell subsets in human immunodeficiency virus 1-infected individuals. J Inf Dis. 2003;187:26–37. doi: 10.1086/345957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campillo-Gimenez L, Laforge M, Fay M, Brussel A, Cumont MC, Monceaux V, Diop O, et al. Nonpathogenesis of SIV infection is associated with reduced inflammation and recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to lymph nodes, not to lack of an interferon type I response, during the acute phase. J Virol. 2009;84:1836–1846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01496-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chehimi J, Campbell DE, Azzoni L, Bacheller D, Papasavvas E, Jerandi G, Mounzer K, et al. Persistent decreases in blood plasmacytoid dendritic cell number and function despite effective highly active antiretroviral therapy and increased blood myeloid dendritic cells in HIV-infected individuals. J Immunol. 2002;168:4796–4801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donaghy H, Pozniak A, Gazzard B, Qazi N, Gilmour J, Gotch F, Patterson S. Loss of blood CD11c(+) myeloid and CD11c(-) plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients with HIV-1 infection correlates with HIV-1 RNA virus load. Blood. 2001;98:2574–2576. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grassi F, Hosmalin A, McIlroy D, Calvez V, Debre P, Autran B. Depletion in blood CD11c-positive dendritic cells from HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1999;13:759–766. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199905070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pacanowski J, Kahi S, Baillet M, Lebon P, Deveau C, Goujard C, Meyer L, et al. Reduced blood CD123+ (lymphoid) and CD11c+ (myeloid) dendritic cell numbers in primary HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2001;98:3016–3021. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabado RL, O’Brien M, Subedi A, Qin L, Hu N, Taylor E, Dibben O, et al. Evidence of dysregulation of dendritic cells in primary HIV infection. Blood. 2010;116:3839–3852. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-273763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soumelis V, Scott I, Gheyas F, Bouhour D, Cozon G, Cotte L, Huang L, et al. Depletion of circulating natural type 1 interferon-producing cells in HIV-infected AIDS patients. Blood. 2001;98:906–912. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wijewardana V, Soloff AC, Liu X, Brown KN, Barratt-Boyes SM. Early myeloid dendritic cell dysregulation is predictive of disease progression in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. PLoS Path. 2010;6:e1001235. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown KN, Trichel A, Barratt-Boyes SM. Parallel loss of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells from blood and lymphoid tissue in simian AIDS. J Immunol. 2007;178:6958–6967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown KN, Wijewardana V, Liu X, Barratt-Boyes SM. Rapid influx and death of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in lymph nodes mediate depletion in acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. PLoS Path. 2009;5:e1000413. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruel T, Dupuy S, Demoulins T, Rogez-Kreuz C, Dutrieux J, Corneau A, Cosma A, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell dynamics tune interferon-alfa production in SIV-infected cynomolgus macaques. PLoS Path. 2014;10:e1003915. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwa S, Kannanganat S, Nigam P, Siddiqui M, Shetty RD, Armstrong W, Ansari A, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are recruited to the colorectum and contribute to immune activation during pathogenic SIV infection in rhesus macaques. Blood. 2011;118:2763–2773. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malleret B, Maneglier B, Karlsson I, Lebon P, Nascimbeni M, Perie L, Brochard P, et al. Primary infection with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasmacytoid dendritic cell homing to lymph nodes, type I interferon, and immune suppression. Blood. 2008;112:4598–4608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves RK, Evans TI, Gillis J, Wong FE, Kang G, Li Q, Johnson RP. SIV infection induces accumulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the gut mucosa. J Inf Dis. 2012;206:1462–1468. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wijewardana V, Bouwer AL, Brown KN, Liu X, Barratt-Boyes SM. Accumulation of functionally immature myeloid dendritic cells in lymph nodes of rhesus macaques with acute pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Immunology. 2014;143:146–154. doi: 10.1111/imm.12295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wijewardana V, Kristoff J, Xu C, Ma D, Haret-Richter G, Stock JL, Policicchio BB, et al. Kinetics of myeloid dendritic cell trafficking and activation: impact on progressive, nonprogressive and controlled SIV infections. PLoS Path. 2013;9:e1003600. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wonderlich ER, Wijewardana V, Liu X, Barratt-Boyes SM. Virus-encoded TLR ligands reveal divergent functional responses of mononuclear phagocytes in pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Immunol. 2013;190:2188–2198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klatt NR, Estes JD, Sun X, Ortiz AM, Barber JS, Harris LD, Cervasi B, et al. Loss of mucosal CD103+ DCs and IL-17+ and IL-22+ lymphocytes is associated with mucosal damage in SIV infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:646–657. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Pabst O, Palmqvist C, Marquez G, Forster R, Agace WW. Functional specialization of gut CD103+ dendritic cells in the regulation of tissue-selective T cell homing. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1063–1073. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaensson E, Uronen-Hansson H, Pabst O, Eksteen B, Tian J, Coombes JL, Berg PL, et al. Small intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells display unique functional properties that are conserved between mice and humans. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2139–2149. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall JA, Cannons JL, Grainger JR, Dos Santos LM, Hand TW, Naik S, Wohlfert EA, et al. Essential role for retinoic acid in the promotion of CD4(+) T cell effector responses via retinoic acid receptor alpha. Immunity. 2011;34:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klatt NR, Funderburg NT, Brenchley JM. Microbial translocation, immune activation, and HIV disease. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boasso A, Shearer GM. Chronic innate immune activation as a cause of HIV-1 immunopathogenesis. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosinger SE, Sodora DL, Silvestri G. Generalized immune activation and innate immune responses in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Cur Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:411–418. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283499cf6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sodora DL, Silvestri G. Immune activation and AIDS pathogenesis. AIDS. 2008;22:439–446. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2dbe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cassol E, Cassetta L, Alfano M, Poli G. Macrophage polarization and HIV-1 infection. J Leuk Biol. 2010;87:599–608. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1009673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuroda MJ. Macrophages: do they impact AIDS progression more than CD4 T cells? J Leuk Biol. 2010;87:569–573. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0909626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otani I, Mori K, Sata T, Terao K, Doi K, Akari H, Yoshikawa Y. Accumulation of MAC387+ macrophages in paracortical areas of lymph nodes in rhesus monkeys acutely infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:977–985. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdo TH, Soulas C, Orzechowski K, Button J, Krishnan A, Sugimoto C, Alvarez X, et al. Increased monocyte turnover from bone marrow correlates with severity of SIV encephalitis and CD163 levels in plasma. PLoS Path. 2010;6:e1000842. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasegawa A, Liu H, Ling B, Borda JT, Alvarez X, Sugimoto C, Vinet-Oliphant H, et al. The level of monocyte turnover predicts disease progression in the macaque model of AIDS. Blood. 2009;114:2917–2925. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bull DM, Bookman MA. Isolation and functional characterization of human intestinal mucosal lymphoid cells. J Clin Invest. 1977;59:966–974. doi: 10.1172/JCI108719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortiz AM, DiNapoli SR, Brenchley JM. Macrophages Are phenotypically and functionally diverse across tissues in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected and uninfected Asian macaques. J Virol. 2015;89:5883–5894. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00005-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allers K, Fehr M, Conrad K, Epple HJ, Schurmann D, Geelhaar-Karsch A, Schinnerling K, et al. Macrophages accumulate in the gut mucosa of untreated HIV-infected patients. J Inf Dis. 2014;209:739–748. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kader M, Smith AP, Guiducci C, Wonderlich ER, Normolle D, Watkins SC, Barrat FJ, et al. Blocking TLR7- and TLR9-mediated IFN-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells does not diminish immune activation in early SIV infection. PLoS Path. 2013;9:e1003530. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malleret B, Karlsson I, Maneglier B, Brochard P, Delache B, Andrieu T, Muller-Trutwin M, et al. Effect of SIVmac infection on plasmacytoid and CD1c+ myeloid dendritic cells in cynomolgus macaques. Immunology. 2008;124:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smythies LE, Sellers M, Clements RH, Mosteller-Barnum M, Meng G, Benjamin WH, Orenstein JM, et al. Human intestinal macrophages display profound inflammatory anergy despite avid phagocytic and bacteriocidal activity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:66–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI19229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Prac Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:390–407. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsen T, Goll R, Cui G, Husebekk A, Vonen B, Birketvedt GS, Florholmen J. Tissue levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha correlates with grade of inflammation in untreated ulcerative colitis. Scan J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1312–1320. doi: 10.1080/00365520701409035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lissner D, Schumann M, Batra A, Kredel LI, Kuhl AA, Erben U, May C, et al. Monocyte and M1 macrophage-induced barrier defect contributes to chronic cntestinal inflammation in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1297–1305. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satsu H, Ishimoto Y, Nakano T, Mochizuki T, Iwanaga T, Shimizu M. Induction by activated macrophage-like THP-1 cells of apoptotic and necrotic cell death in intestinal epithelial Caco-2 monolayers via tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Exper Cell Res. 2006;312:3909–3919. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wonderlich ER, Wu WC, Normolle DP, Barratt-Boyes SM. Macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells lose T cell-stimulating function in simian immunodeficiency virus infection associated with diminished IL-12 and IFN-alpha production. J Immunol. 2015;195:3284–3292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cha HR, Chang SY, Chang JH, Kim JO, Yang JY, Kim CH, Kweon MN. Downregulation of Th17 cells in the small intestine by disruption of gut flora in the absence of retinoic acid. J Immunol. 2010;184:6799–6806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scott CL, Aumeunier AM, Mowat AM. Intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells: master regulators of tolerance? Trends Immunol. 2011;32:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raffatellu M, Santos RL, Verhoeven DE, George MD, Wilson RP, Winter SE, Godinez I, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat Med. 2008;14:421–428. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Favre D, Lederer S, Kanwar B, Ma ZM, Proll S, Kasakow Z, Mold J, et al. Critical loss of the balance between Th17 and T regulatory cell populations in pathogenic SIV infection. PLoS Path. 2009;5:e1000295. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chase AJ, Sedaghat AR, German JR, Gama L, Zink MC, Clements JE, Siliciano RF. Severe depletion of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells from the intestinal lamina propria but not peripheral blood or lymph nodes during acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2007;81:12748–12757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00841-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laforge M, Campillo-Gimenez L, Monceaux V, Cumont MC, Hurtrel B, Corbeil J, Zaunders J, et al. HIV/SIV infection primes monocytes and dendritic cells for apoptosis. PLoS Path. 2011;7:e1002087. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demers A, Kang G, Ma F, Lu W, Yuan Z, Li Y, Lewis M, et al. The mucosal expression pattern of interferon-epsilon in rhesus macaques. J Leuk Biol. 2014;96:1101–1107. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0214-088RRR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nascimbeni M, Perie L, Chorro L, Diocou S, Kreitmann L, Louis S, Garderet L, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells accumulate in spleens from chronically HIV-infected patients but barely participate in interferon-alpha expression. Blood. 2009;113:6112–6119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]