Abstract

Several popularly abused drugs, such as nicotine (tobacco) and THC (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol) (marihuana) are commonly self-administered by the smoked route. Although the neuronal substrates mediating the effect of smoked drugs are of interest, studies of their acute actions in living human brain has been difficult due to the unique constraints imposed by neuroimaging equipment and scanning environments. We have previously reported a device for the self-administration of smoked drugs with concurrent blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) fMRI imaging. Here we report improvements to the device which result in improved drug delivery to the smoker. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GCMS) analysis of nicotine recovered from filter extracts revealed that the amount of nicotine delivered to subjects smoking with our original device was reduced by approximately 44% compared to nicotine delivered by cigarettes smoked normally. Improvements were made to the smoke delivery component of our apparatus in an attempt to improve drug delivery, while not interfering with collection of MRI data.

Nicotine plasma levels in 9 subjects smoking both with and without the improved smoking device in the laboratory were not significantly different. Similarly, the device produced no significant difference in either ratings of the subjective effects of nicotine, or changes in cardiovascular parameters in this experiment. The improved device does not interfere with typical drug effects produced by normal smoking. Phantom scans revealed that BOLD signal was not found to be altered by the (in-bore) installation and operation of the improved device. Preliminary data analysis of smoking induced changes in the BOLD response to visual stimulation suggest that this response is not affected by the improved device, the act of smoking, air puffing, nicotine, or other components of cigarette smoke. The improved device does not interfere with the collection of MRI neuroimaging data. Use of this device will facilitate investigations of the acute neuronal effects of smoked drugs.

Keywords: fMRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Self-Administration, Smoked Drugs, Smoking Device

INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, neuroimaging has revolutionized the study of the brain, and it holds great promise for both understanding cause of, and developing treatments for, substance abuse. However, to date, almost no neuroimaging data have been collected during tobacco smoking. Progress in this area is limited by several practical factors, most significantly, the difficulty in constructing a device that would allow smoking to occur safely within positron emission tomography (PET) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners, a problem that we have recently overcome. We report refinements to the design and further validation of a nonferrous MRI-safe smoking device that allows continuous functional MRI (fMRI) scanning to occur before, during, and after self-administration of smoked drugs by research subjects within the scanner bore. Use of this device allows evaluation of the effects of smoked nicotine on local hemodynamic changes as indicated by changes in blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal. Measurements of changes in concurrent subjective ratings of drug effect provide a means of correlating observed changes in BOLD with relevant components of the drug-taking experience. Similar analytical techniques can be used to further dissect the additional effects of manipulations of nicotine dependence state and withdrawal state on nicotine-induced changes in BOLD signal.

A fair number of neuroimaging investigations of the functional effects of abused drugs on living human brain have been reported, reflecting both technological advances in both MRI and PET technologies, as well growing interest in identification of the neuronal substrates of drug action in brain. Regardless of the imaging modality chosen, a variety of constraints are imposed by the nature of the scanning environment. First, imaging requires that the research participant remain motionless or nearly so to maximize the quality of the images acquired. Related to this is the requirement that the scan duration be sufficiently long to measure a substantial fraction of the temporal dynamics of a drug effect. These two constraints typically dictate the use of rapid routes of drug administration in pharmacologic imaging studies. The direct neuronal effects of a number of drugs have been investigated using the intravenous route in fMRI neuroimaging experiments in human participants, for example, cocaine,1–4 heroin,5,6 and nicotine.7,8. Although intravenous drug administrations offer some advantages over other routes of administration in the context of an experiment (maximizes bioavailability and rate of onset (if desired), and allows tight control over dose and rate), many drugs are not typically self-administered intravenously by drug users in natural settings. Results from several imaging studies have suggested that the neuronal response to a drug can be modified by non-drug factors such as expectation,3,9,10 and the presence of conditioned reinforcers,11 which highlights the importance of using naturalistic methods of drug delivery in studies of reinforcement.

We have previously reported a device for the self-administration of smoked drugs such as marihuana and nicotine within an fMRI scanning environment.12 Based on findings that the initial device design did not deliver amounts of nicotine comparable to smoking without the device, both the design and installation of the smoke delivery component of the device were modified resulting in dramatic improvements to drug delivery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

Our previous device allowed subjects to smoke cigarettes during fMRI neuroimaging in a natural manner. The device was constructed to contain the expired smoke and smoke generated by the burning cigarette so that residual odors and other smoke byproducts would not contaminate the air or the equipment in the scanning environment.

In order to produce the most natural smoking experience, the device was designed to be comfortable to use and not distracting to the participants. It did not block the visual field of the participants or prevent them from interacting with other data collection devices such as button pads, or physiological monitoring devices. The initial design met these goals, and delivered physiologically active doses of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) to subjects who smoked marijuana through the device. However, the same properties of drugs that enhance bioavailability and facilitate absorption through biological membranes also tend to make drugs adhere to nonbiological surfaces such as the interior of smoke delivery systems. We previously reported reductions in THC delivery associated with smoking marihuana using our original smoking device of approximately 44%. Although this could be overcome by increasing the potency or the amount of marijuana smoked, this compensatory strategy is less desirable for studies of nicotine administered by tobacco cigarette smoking.

Our modified device reduces surface area within the cigarette combustion chamber and inhalation tubing by approximately 6 fold (83%) compared to our old system in order to improve drug delivery. In addition, the new device was designed to have airflow properties similar to those provided by cigarettes and to deliver fresh smoke that is as much as possible unaltered by the device in order to preserve conditioned reinforcing aspects of smoking, such as taste and smell of smoke, as well as airway sensation. Because the initial system was designed to be modular in order to facilitate installation, removal, and cleaning, we were able to preserve the existing exhaust system unmodified.

Smoke Delivery System

The smoke delivery system is made up of a ventilated combustion chamber that houses the cigarette, and provides attachment points for both inhalation tubing and ventilation tubing (See Figure 1). The combustion chamber was constructed from a 2 L cylindrical polycarbonate canister with a tight-fitting lid. A hole was bored into the bottom of the canister to accept a number 4 rubber stopper (top diameter: 25.4 mm, bottom diameter 19.0 mm, height: 25.4 mm). The cigarette holder was made from a 2.5 mm section of smooth 10mm o.d. Pyrex/borosilicate glass tubing coupled to a barbed nylon tubing connector with a 2.5 mm length of rubber tubing. The cigarette holder was placed into a hole in the rubber stopper which was inserted into the bottom of the canister. On the other side of the rubber stopper, another nylon barbed tubing connector provided the attachment point for a length of nylon tubing (8 mm i.d.) slightly less than 100 cm in length, which terminated in a nylon mouthpiece and together comprised the inhalation tubing.

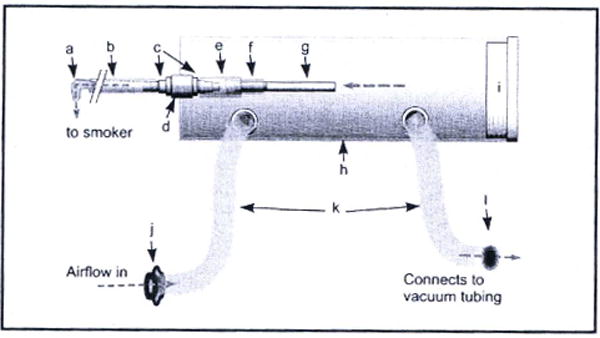

Figure 1.

A diagram of the smoke delivery system. a) mouthpiece (35 inches of inhalation tubing connect the combustion chamber to the mouthpiece), b) inhalation tubing, c) flanged nylon tubing connectors, d) rubber stopper, e) 1 inch rubber tubing, f) cigarette holder (borosilicate glass tubing), g) cigarette, h) 2 L polycarbonate canister, i) tight-fitting lid, j) one way valve for air inflow, k) corrugated plastic respiratory tubing, l) one way valve for air outflow connecting to inline exhaust system. Gray dotted lines indicate the flow of air through the device. Airflow through the cigarette and out the mouthpiece is generated by participant puffing. Airflow through the corrugated tubing is generated by the exhaust system.

This tubing size was chosen to strike a balance between two observations made during preliminary evaluations: 1) test smokers objected strongly to the exertion of extra effort during puffing that was required when using prototype devices that restricted the airflow from the cigarette by means of smaller-bored tubing, and 2) smokers also objected strongly to prototype devices which used larger tubing because of the increased dead space which delayed smoke arrival to the mouth, and then served as a reservoir trapping rapidly staling smoke from previous puffs that would then contaminate subsequent puffs. As a result, we used components with inner diameters that were the same as the outer diameter of a typical tobacco cigarette.

The ventilation tubing was made from standard corrugated respiratory tubing and was attached to two large holes bored into the one side of the cylindrical canister forming the combustion chamber. One of these ventilation tubes was coupled to the main exhaust system in order to provide airflow through the device for maintenance of combustion during times when the cigarette was not actively being smoked. The other ventilation tube was fitted with an inexpensive one-way valve (CPR-Pro, Valley Cottage, NY) to prevent smoke from leaking from the device in the event that positive pressure developed within the device (as could happen if subjects accidentally coughed into or purposefully blew air into the inhalation tubing).

Exhaust System

A critical feature of smoking devices that are intended to be used in hospital MRI scanning suites is a mechanism to capture both side-stream smoke from the cigarette, and smoke from subject exhalations. Escaped smoke contaminates the scanning environment with unacceptable smoke odor, and also potentially deposits residues on surfaces inside the bore and on sensitive electronics inside the head coil, possibly leading to internal arcing and coil failure. Ideally, part of the smoke capture apparatus would fit within the radiofrequency (RF) head coil used for imaging in order to remove exhaled smoke before it could contact the RF coil.

As described in detail in Frederick et al 2007,12 a smoke exhaust system was constructed that would create airflow around the head that would draw all exhaled smoke into an exhaust hose and rapidly vent it from the building (Figure 2). This has a number of advantages. First, no component of the exhaust system actually touches the subject, so there is no uncomfortable or distracting equipment contacting the smoker’s face, and no need to individually fit components to each study participant. Second, since the exhaust pipe collects air from all around the smoker’s face and head into the exhaust pipe, any smoke that initially escapes during a cough is rapidly recaptured by the system. After extensive testing, we have found that the exhaust system very effectively captures smoke produced during experimental coughing.

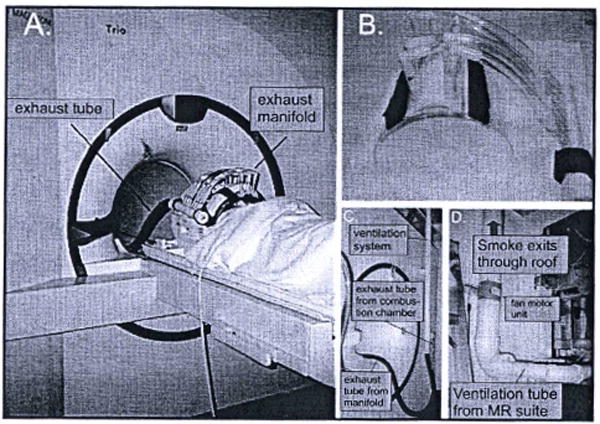

Figure 2.

Exhaust system components. A. Exhaust system installed. B. Close-up of the exhaust manifold and face shield. C. Exhaust tube exiting the “magnet” or “head” end of the magnet bore, and coupling to the exhaust pipe in the ceiling. D. Exhaust fan outside the magnet room. Reprinted from Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 87(1), Frederick B, Lindsey KP, Nickerson LD, Ryan ET, Lukas SE, An MR-compatible device for delivering smoked marijuana during functional imaging, 81-89, Copyright (2007), with permission from Elsevier.

The in-coil exhaust system was constructed from a half cylinder of acrylic that conformed to the inner diameter of the RF coil (26.7 cm o.d., 64 mm wall thickness). This formed a shield, which extended from the bridge of the nose, just below the eyes, to halfway down the neck. Along the central axis over the nose, a longitudinal slice of PVC pipe was glued on to give more clearance for the nose. Seven 190 mm diameter nylon barbed tube fittings were mounted on this pipe to provide exhaust ports, and were connected to an exhaust manifold using vinyl tubing. The number, position, and size of the exhaust ports were varied during the design process; the final configuration provided high, uniform airflow over the nose and mouth, was compatible with the spacing of the conductors of the radiofrequency coil, and did not create uncomfortable suction for the subject (large exhaust ports right over the nose or mouth tended to make inhalation difficult) or drying of the eyes or lips (Figure 2A and 2B)

The exhaust manifold was attached to a 3.8 cm diameter fiexible hose leading to a coupling at the back of the magnet to a permanently mounted exhaust system. This consisted of a 5.08 cm PVC pipe that exited the magnet room through a waveguide, and was coupled to a 10.2 cm PVC pipe with an inline 12V, 240 CFM duct fan that vented the smoke out of the building (Figure 2C and 2D). The original design of our exhaust system has not been modified.

INSTALLATION AND USAGE

For use in a smoking experiment, the smoking chamber is positioned on a foam holder inside the bore of the magnet just behind the subject’s head (Figure 3). The face shield is secured to the RF coil with Velcro straps, and the exhaust tubing from the face mask is attached to the fixed tubing at the magnet end. During the scan, the lid of the combustion chamber is removed, and the cigarette is lit using standard matches. The lid of the combustion chamber is then replaced, and the subject can inhale smoke from the cigarette either ad libitum or in a paced manner in response to cues. The Siemens Trio 3T scanner has a bore camera that has been useful to verify from the control room that the cigarette is still burning and that puffing is occurring on schedule.

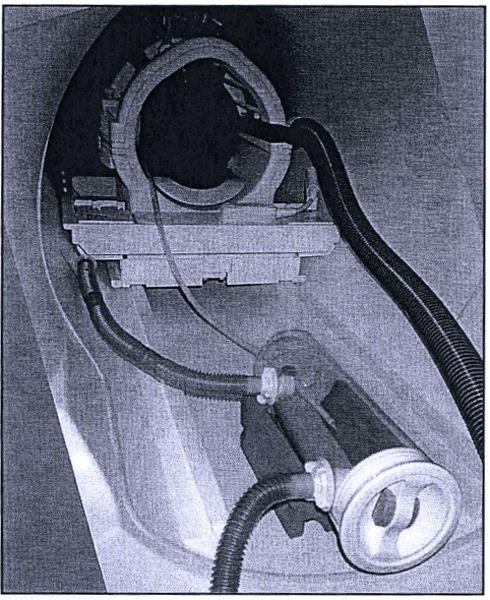

Figure 3.

Smoking device installation. The improved smoke delivery apparatus and original exhaust system installed in the bore of the Siemens Trio MRI scanner. A pilot study is in progress and the smoker’s head is visible within the head coil, along with exhaust manifold components connected to large-diameter blue vacuum tubing. The device rests on a cylindrically concave piece of red foam that was originally intended for stabilization of cylindrical phantoms. A damp paper towel has been placed underneath the cigarette in case smoldering particles fall off the cigarette onto the plastic surface of the combustion chamber. Note the brown discoloration of the ventilation outflow tubing where it emerges from the combustion chamber at the bottom of the image. This discoloration results from deposition of sidestream smoke residue, including tar and nicotine, onto the interior surface of the ventilation tubing over time. Just out of the field of view, this ventilation outflow tubing joins with the vacuum line with a T-connector.

When the subject has finished smoking, the airflow through the chamber continues, and clears the remaining smoke from the cigarette from the chamber, and the very mild suction clears the smoke from the mouthpiece tubing. When the imaging session is over, the smoking device remains closed while it is removed from the MR suite to be opened at another location for cleaning. This prevents any smoke or odor from escaping into the MR suite. Inhalation tubing is replaced for every scan to prevent contamination of the taste and odor of fresh smoke with stale smoke residue from the interior of previously used tubing.

VALIDATION

Ideally; an MRI-safe smoking device must allow a subject to smoke while lying in the magnet, and capture all smoke – preventing it from entering the magnet room. A cigarette smoked with the device must deliver a comparable amount of nicotine to a cigarette smoked without the device. Additionally, the nicotine self-administered via smoking through the smoking device must produce the same subjective and physiological effects as those produced by nicotine smoked without the device. And finally, the device must not interfere with fMRI data acquisition, either by increasing patient motion, or by directly affecting the acquired MR signal (through electronic noise or field distortion). We performed a variety of tests in order to validate the performance of the device with attention to these requirements. All system tests involving human subjects, and the fMRI study of tobacco smoking, were approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Delivery of Nicotine

GCIMS analysis of cigarette filter extracts

We conducted an experiment to estimate the relative amount of nicotine trapped by our original smoke delivery device. A single nicotine dependent smoker smoked a total of three Marlboro “Red” type cigarettes through the original smoking device on the same paced smoking schedule used in our other experiments (5 minutes of puffing on 21 second intervals), and three identical cigarettes in the same manner without the device (6 cigarettes total). In the with-device condition, the filter was removed from the cigarette and placed in the mouthpiece of the inhalation tubing. A third experiment was performed in which cigarettes were smoked with filters intact to assess the impact of potentially altered airflow dynamics on the nicotine released from each cigarette. All three conditions were alternated. Smoke residue from each filter was extracted with 10 ml of methanol and analyzed using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). Analysis was performed on an HP 5970 mass spectrometer connected to an HP 5890 series gas chromatograph (Hewlett Packard/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) with a DB-5MS fused silica capillary column (15 mm length, 0.25 μm film thickness, J&W Scientific/Agilent product 122-5512, Santa Clara, CA). The injector and ion source temperatures were set to 275°C and the column oven temperature was maintained at 70°C for one minute after injection, then increased by 20°C/min to a maximum temperature of 250°C, then maintained at 250°C for 5 minutes (12 minutes total). Nicotine was found to elute with a retention time of 5.89 minutes. Standards were prepared from (−) nicotine tartrate (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in methanol, and quantification was performed in select ion monitoring (SIM) mode using mass 162.

In vivo plasma nicotine levels

We conducted a series of experiments in nine healthy nicotine-abstinent smokers in our laboratory to assess the nicotine delivery via the improved smoking device. Participants were asked to remain abstinent from nicotine starting at 10:00 pm the night before each experimental visit. Smoking visits were scheduled in the morning around 9:00am, and abstinence was verified before each experiment using a hand-held meter to detect carbon monoxide in participant exhalations (Vitalograph CO meter Lenexa, KS). On each visit, each participant smoked one Marlboro “Red”-type tobacco cigarette using the smoking device with concurrent blood sampling. Samples were collected every 2 minutes for the first 15 minutes of the study (during 5 minutes of baseline, 5 minutes of smoking, and 5 minutes post-smoking) and every 4 minutes for the remainder of the 25 minute study. Cigarettes were smoked over 5 minutes on a paced smoking schedule (one puff every 21 seconds, 14 puffs maximum in total). Subjects returned to the laboratory on another day to smoke the same type cigarette without the device. The two smoking conditions were separated by at least 5 days, and presented in counterbalanced order.

Physiological and subjective effects

Physiological and subjective ratings of drug effect were collected in all participants during the laboratory device validation experiment described above. Heart rate was recorded every minute throughout the 25 minute procedure and blood pressure was recorded every 3 minutes. A computerized subjective ratings questionnaire was administered every 150 seconds and consisted of the following 7 questions: How high do you feel right now? How much do you crave a cigarette right now? How much do you like the drug effect you’re experiencing right now? How much do you dislike the drug effect you’re experiencing right now? How anxious do you feel right now? How jittery do you feel right now? How strongly do you feel drug effects right now? Participants indicated their responses on a visual analog scale by means of a computer rollerball mouse device and keypress using Presentation@ software (Version 0.92, Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc., Albany, CA). Scale anchor points were “not at all” and “extremely”.

Effects on scan quality

Phantom acquisitions with the smoking device vs. without the smoking device

Since one of the main goals of the device modifications was to minimize surface area between the cigarette and the research participant, a smoke delivery apparatus was developed that would be placed in the scanner bore along with the vacuum tube from the exhaust manifold and along with the research participant. Tests were performed to evaluate the impact of all components of the improved smoking device on MR image quality. In order to assess whether the device produced “noise” in the images or other artifacts, two functional runs were performed on a spherical test phantom either with the smoking device installed in the magnet, or without the smoking apparatus, using precisely the same protocol employed for smoking studies.

Assessment of the effects of device, puffing, and smoke self-administration on BOLD signal change in visual cortex

In order to further assess the impact of the smoking device during an fMRI scan, including the impact of the device itself, cigarette lighting procedure, motion associated with air and smoke puffing, as well as the impact of smoke inhalation, a pilot study of the BOLD response to a standard visual stimulation paradigm was conducted (see Frederick, 200712). Data were acquired using a Siemens 3T Trio whole body scanner with a transmit-receive quadrature birdcage head coil. After initial localizer scans were complete, an arterial spin labeled (ASL) image was obtained to measure baseline blood flow (ASL data were acquired both before and after our BOLD acquisition with concurrent smoking as part of our standard tobacco smoking protocol; it is not relevant to evaluation of the device function, and will not be discussed further in this manuscript). fMRI data were then collected as follows: single shot gradient echo EPI, TR/TE= 3000/18ms, 64×64 matrix, 220×220 mm FOV, 50 interleaved transverse slices 3mm thick with no gap, 1 average, 500 repetitions (25:00). This scan was followed a high resolution T1-weighted MPRAGE3D anatomical image (FOV=256×256×170mm, 256×256×128 (8:59)).

The subject’s heart rate and SaO2 levels were continuously monitored with a patient monitoring device (In Vivo MRI Devices, Orlando, FL), timestamped, and recorded on a PC for correlation with the fMRI data. In order to determine subjective mood states during tobacco smoking, computerized visual analog scales were presented to the subject during the fMRI scans using Presentation@ software (Version 0.92, Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc., Albany, CA) with a rear-projection system. We employed a commercial MRI-safe 4-button fiber optic keypad (Fiber optic Response Pad (fORP), Current Designs, Inc.), to move a cursor on the scale. A set of scales (Crave, High, Like drug, Anxious, Irritable, Feel drug effects, Dislike drug) were presented for 9 seconds apiece on a 150 second cycle, and the subject’s responses were recorded. The presentation program also provided the subject with auditory cues to puff on the smoking device during air puffing and smoking periods. The BOLD scan was 25 minutes long, and consisted of the following functional blocks: Five minutes baseline data were collected followed by 5 minutes of air puffing at 21 second intervals. Air puffing was immediately followed by 5 minutes of smoke puffing (smoking) on the same schedule. BOLD data acquisition continued after the end of the smoking period for 10 more minutes, broken down into two 5 minute blocks (for comparison of equal time periods in graphs) designated postsmoking1 and postsmoking.2 In addition, the presentation program provided a periodic checkerboard visual stimulus to control for global blood flow changes (8 Hz black and white reversing logarithmic radial checkerboard, off-on-off-on-off in 12s epochs, presented every 150s). The fORP also provided an interface to synchronize the presentation program to a scanner-generated trigger signal.

fMRI data processing was carried out using FEAT (fMRI Expert Analysis Tool) Version 5.92, part of FSL (FMRIB’s Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uklfsl). The following pre-statistics processing was applied: motion correction using MCFLIRT13; spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of FWHM 5 mm; grand-mean intensity normalization of the entire 40 dataset by a single multiplicative factor; and highpass temporal filtering (Gaussian weighted least-squares straight line fitting, with sigma=24 seconds). Time-series statistical analysis was carried out using FILM with local autocorrelation correction.14 Z (Gaussianized T) statistic images were thresholded using clusters determined by Z>2.3 and a (corrected) cluster significance threshold of P=0.05.15

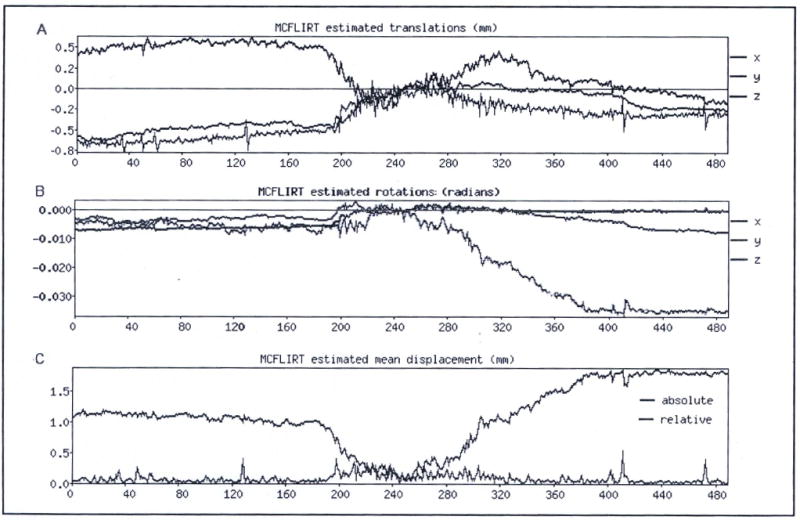

Since collection of high quality fMRI data depends largely on the degree to which research participants can remain motionless in the scanner, participant motion is of particular concern in our experiment for two reasons: first, the long duration of the BOLD scan, and second, the requirement that subjects puff air and smoke during the scan. The length of the BOLD acquisition was determined by the time course of the onset and offset of nicotine effects. Even with rapid routes of administration such as smoking, maximal drug effects can occur no sooner than the time at which smoking ends, and the time course of the return of drug effects to baseline is dictated by properties of the drug itself and properties of the biological system(s) on which it acts. As a result, the BOLD acquisition was long, and the complexity of pharmacologic MRI studies necessitates additional control scans before and after the BOLD session which contribute to the total amount of time the subject spends in the scanner, and to subject fatigue. Additionally, puffing on air or smoke causes expansion of the thorax to a greater extent than normal breathing, and this tends to move the participant’s head within the head coil. To combat these factors, we spent extra time during positioning of the participant on the scanner bed and in the bore to ensure that he or she was as comfortable as possible and we applied foam restraints around the head to discourage head motion. We also took great care to ensure that the act of smoking was as naturalistic as possible (no. undue effort was required to inhale smoke). Subjects were motivated to attempt to remain motionless by offering them a $25 “motion bonus” which they could earn by keeping translational head motion less than 3 mm and rotational head motion less than 3 degrees in any spatial dimension (the degree of motion was determined using the motion timecourses output from FSL’s 3D motion correction routine during data preprocessing). This approach worked quite well to reduce motion; the subject motion is quite acceptable, even during the smoking period, and it is likely that a large component of the apparent motion is actually scanner drift over the long acquisition. Even with the additional apparent motion produced by scanner signal drift over time, 85% of subjects studied using this paradigm met the motion criteria described above. Because of the extremely long acquisition, and the drift component of the motion, we used a somewhat relaxed motion standard; scans were discarded if either a) the absolute displacement in any direction over the entire timecourse was greater than 3mm, or b) there was greater than 0.5 pixels displacement in any direction over a single time point. Typical motion parameters during the fMRI session measured during the motion correction process for a single subject are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Typical motion time courses. A. Rotational motion in a single typical subject who smoked a tobacco cigarette during the BOLD fMRI scan acquisition. B. Translational motion in the same subject. C. Summary of maximum motion values at every time point.

All BOLD data preprocessing and analysis was performed in FSL (FMRIB Software Library, Oxford UK). The entire BOLD signal timecourse was preprocessed, and then analyzed with GLM methods. After fitting, the timecourse of BOLD signal in a region of visual cortex that was activated during all the experimental conditions was isolated (See Figure 8). In order to determine the effect of the smoking experiment on the fMRI data, we compared the visual stimulation data from various subsections of the fMRI experiment. The 10 visual stimulation epochs were isolated from this timecourse and graphed together for comparison (Figure 9). Two visual stimulation epochs were contained within each of the 5 five-minute blocks of the smoking session. In order, these were presmoking, air puffing, and tobacco smoking, followed by two blocks designated postsmoking1 and postsmoking2 to facilitate comparisons with other blocks. Timecourses were percentage normalized.

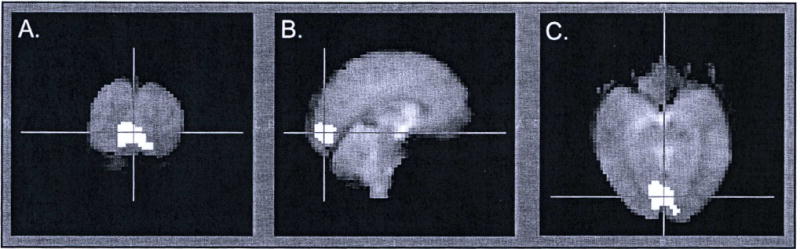

Figure 8.

Region of maximal BOLD signal change in response to visual stimulus. A. Coronal slice through the occipital cortical region of maximal activation. B. Sagittal slice through the region. C. Axial slice through the region.

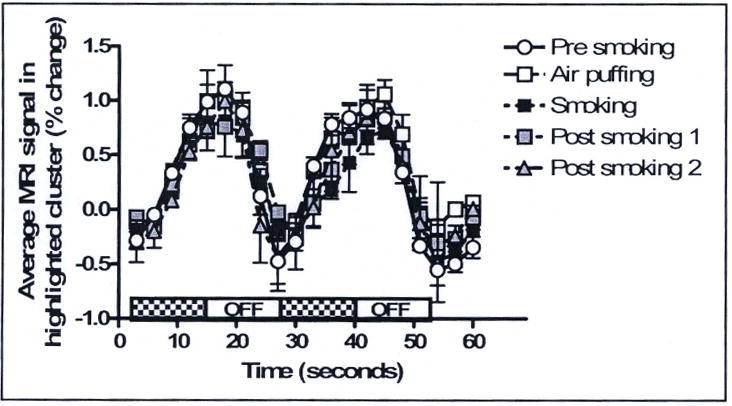

Figure 9.

Time course of BOLD signal change in the region with maximal response to visual stimulus. Curves represent the average and standard deviation of 2 visual stimulations collected during each 5-minute epoch of a typical smoking experiment –presmoking, air puffing, tobacco smoking, and postsmoking 1 and 2. Each visual stimulation consisted of two repetitions of a radial checkerboard flashing at 8Hz for 12 seconds, alternating with fixation for 12 seconds.

RESULTS

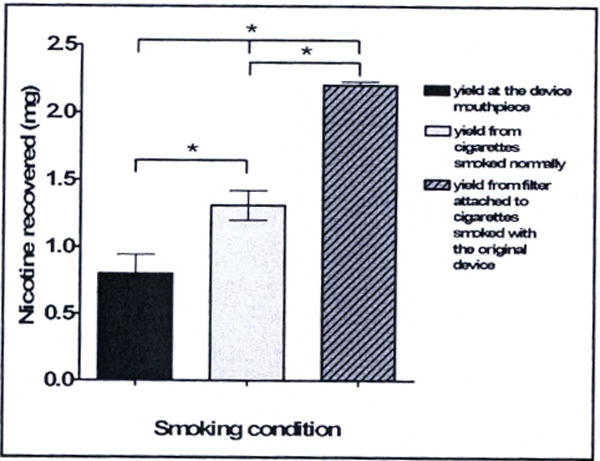

The results from the GC/MS analysis of nicotine contained in extracts from the filters of cigarettes smoked with or without our original smoking device are shown in Figure 5. Bars indicate the mean and standard deviations of 3 cigarette filters extracted in each of three conditions in which cigarettes were smoked using the paced smoking schedule described above. The dark gray bar indicates amount of nicotine recovered from the filters of cigarettes smoked through the smoking device (filters were removed from cigarettes and placed at the mouthpiece end of the inhalation tubing). The light gray bar indicates the amount of nicotine recovered from filters of cigarettes smoked by hand in the usual manner. The striped bar indicates the amount of nicotine recovered from the filters of cigarettes smoked with the smoking device at the cigarette-proximal end of the device, in order to measure the impact of possibly altered airflow and puff dynamics on nicotine release from the cigarette. An analysis of variance showed the effect of the device was significant (F(2,3) = 15.06, p = 0.03), and together suggest that 40% of nicotine appears to be retained within the device, likely by adhesion to various surfaces that are in contact with smoke within the combustion chamber and within the inhalation tubing and mouthpiece, rather than being lost to increased pyrolysis caused by altered airflow dynamics through the cigarette when puffing through the device. Indeed, 40% more nicotine was recovered from filters when they were left attached to the cigarette and the cigarette was smoked with the original device. The results for nicotine delivery at the subject-proximal end of the smoke delivery apparatus are fairly consistent with the 44% reduction in plasma THC when using the original smoking device compared to smoking marihuana by hand that was reported by Frederick and colleagues previously.12

Figure 5.

GC/MS of filter extracts. Bars represent the mean and standard deviation of the amount of nicotine extracted from filter tips of cigarettes smoked with or without the original smoking device. Three cigarette filters were extracted per condition. All cigarettes were smoked by a single nicotine dependent cigarette smoker for maximum reproducibility, and smoking conditions were alternated to diminish test order effects. Nicotine content in the filters collected during the with device condition were 40% lower than in the filters collected during the without device condition.

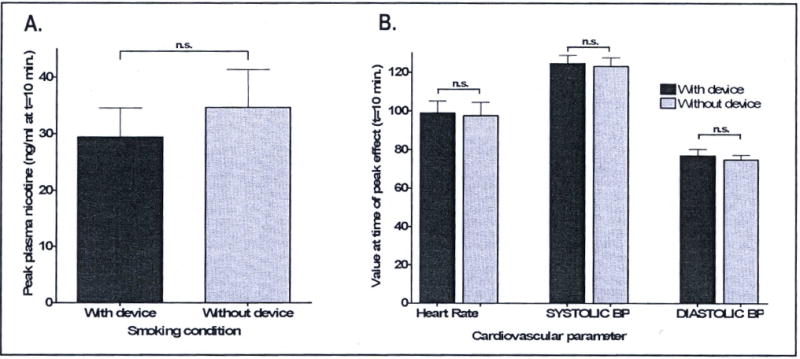

A new smoke delivery apparatus was constructed (see Figure 1) and an investigation of the drug delivery from our improved smoke delivery apparatus was performed by analyzing plasma nicotine levels in a larger group of cigarette smokers smoking standard Marlboro “Red” type cigarettes on the same paced smoking schedule with or without the smoking device. This experiment was conducted in a laboratory setting (outside the MRI scanner) to facilitate blood draws and other technical aspects of the experiment. Peak plasma nicotine levels were observed in the sample collected at the time that smoking ended (10 minutes from the start of the experiment, and 5 minutes after smoking began). Peak plasma levels for both conditions are shown in Figure 6. No difference in peak plasma levels (or time to peak) were observed between the with-device and without-device cigarette smoking conditions (paired t-test, 2-tailed, p=0.48).

Figure 6.

Plasma nicotine levels. Data represent the average peak nicotine levels in 9 healthy smokers smoking with the new smoke delivery device (dark bar) and without the device (lighter bar). Peak nicotine levels were detected in the 10-minute sample concurrent with the cessation of acute smoking in both with-device and without-device conditions.

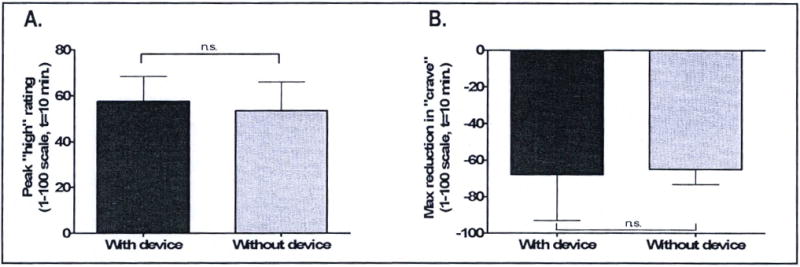

As expected, given that no statistically significant differences were found in nicotine levels produced by smoking with the new device compared to without the device, no significant differences were found when subjective ratings of drug effect and cardiovascular effects of nicotine were compared between the two smoking conditions. Peak subjective data from questionnaire entries “How high do you feel right now?”, and “How much do you crave a cigarette right now?” are shown in Figure 7. Peak changes in ratings on both these questions were observed at the end of the smoking period, concurrent with peak plasma nicotine levels. No significant differences in peak subjective ratings (or time to peak) were observed between the with-device and without device smoking conditions (paired t-test, 2-tailed, p=0.62 (high) and p=0.65 (crave)). Differences between the with-device and without-device smoking conditions for “Feel drug effect?”, “Like drug?”, “Dislike drug?”, “Jittery?”, and “Anxious?” are not shown, but were also found not to be significant. Furthermore, nicotine delivered by smoking through the smoking device produced the same changes in heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure as nicotine delivered by smoking by hand without the device (paired t-tests, 2-tailed p=0.66 for difference in heart rate; p=0.50 for difference in systolic blood pressure; p=0.27 for difference in diastolic blood pressure).

Figure 7.

Heart rate, blood pressure and subjective ratings of cigarette high, and “crave a cigarette.” Data represent the average peak heart rate (beats per minute) and peak systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels (mm Hg). Peak levels in all cardiovascular parameters measured occurred at the end of the smoking period (the 10 minute time point) concurrent with peak plasma nicotine.

In order to assess the performance of the smoking device during collection of fMRI data, we analyzed data obtained during a BOLD imaging experiment with concurrent tobacco smoking using our new smoking device. A visual stimulation paradigm was interleaved during the BOLD acquisition with 2 epochs of 12 seconds of flashing checker-board alternating with 12 seconds fixation every 250 seconds. This procedure was developed initially as a control to allow detection of drug-induced changes in neurovascular coupling in regions previously shown not to be influenced by nicotine.7 Figure 8A shows the region of visual cortex that was activated by the visual stimulus regardless of the experimental conditions (data from presmoking, air-puffing, during smoking, and post-smoking periods contribute to defining this region). Figure 9 shows the average of two BOLD signal timecourses for the two visual stimulation epochs that occurred during each of the 5 different blocks in the tobacco smoking experiment.

DISCUSSION

A wide variety of strategies other than concurrent cigarette smoking have been used in fMRI studies of the effects of nicotine in human smokers. These include allowing subjects to smoke during a break in the scanning session,16 allowing subjects to smoke before the scan,17,19 performing comparisons of scans acquired in nicotine abstinence with scans acquired (typically on another day) after nicotine replacement (gum or patch),19–23 administering subcutaneous nicotine before scanning (with saline control on a different day),24 or administering intravenous nicotine infusion during the scan.7,8 These methods involve either routes of nicotine delivery other than smoking, or delaying data acquisition until smoking is complete (and peak nicotine effects are subsiding). Here we report refinements to a device that allows cigarette smoking during fMRI neuroimaging, and produces nicotine plasma levels, cardiovascular changes, and subjective ratings of drug effect typical of those produced by smoking in the usual manner.

The previous smoke delivery device developed in our laboratory for use with marihuana cigarettes was found to deliver approximately 44% of the THC that was delivered by smoking marihuana cigarettes normally.12 Although increasing the amount of marihuana smoked by the participants partly compensated for the reduction in drug delivery in our marihuana studies to the point where participants reported comparable levels of drug effect regardless of whether they smoked marihuana with the original smoking device or without it, plasma THC levels resulting from smoking marihuana with the device were significantly different from those produced by without-device marihuana smoking (p=0.03). Based on similarities in the nature of marihuana and tobacco, and also the chemical properties of THC and nicotine,25 a similar attenuation of nicotine delivery was anticipated. In order to rapidly assess the degree of nicotine retention in the original smoking device, an experiment was conducted in which GC/MS was used to analyze relative amounts of nicotine extracted from the filter tips of cigarettes smoked with vs. without the original device and delivery was estimated to be approximately 40% (See Figure 5). Both the results from the GC/MS analysis and the plasma THC levels observed in the previous experiments were consistent with significant drug loss to the interior of the original device. Alternatively, it is possible that altered airflow dynamics associated with the original smoke delivery apparatus increased drug pyrolysis during smoking. This could also potentially account for the reductions observed in the bioavailability of THC, and in the nicotine recovered from filter extracts. However, results from an additional experiment in which GCMS was used to analyze cigarette filter extracts indicated that when the influence of the smoking device on airflow dynamics was held constant, nicotine yield sampled at a point near the smoker’s lips was dramatically reduced compared to nicotine yield sampled near the cigarette.

It was hypothesized that nicotine (as well as tar and other lipophilic components of cigarette smoke) was trapped within the previous device by adherence to plastic materials used in the construction of or initial smoke delivery device. A new smaller smoke delivery device was developed in an attempt to minimize the interior surface area for better delivery of lipophilic smoked drugs. In addition, the smaller smoke delivery device was designed to be positioned within the scanner bore to further minimize the surface area between the cigarette and the research participant, and maximize the amount of nicotine and other smoke components available to the participant. Since drug delivery is determined by the smoke delivery component of the apparatus, the exhaust system component was unchanged. The new smoke delivery apparatus was tested in the laboratory. Nine healthy smokers smoked Marlboro “Red” type cigarettes both with the new smoking device and without the new smoking device on separate study days. No significant difference was found when levels achieved during the with-device condition were compared to levels achieved in the without device condition (See Figure 6.). In addition, no significant differences were found in nicotine associated cardiovascular changes, and subjective ratings of cigarette effect between the two smoking conditions (See Figure 7).

Although care was taken to reduce the surface area of the interior of the smoke delivery apparatus to a minimum, it is likely that a measurable fraction of the nicotine contained within the tobacco smoke continues to be trapped within the device and within the inhalation tubing. However, a number of reports have suggested that tobacco smokers exhibit compensatory smoking behavior, in which attempts are made to compensate for reduced nicotine content in smoke by altering one or more puffing parameters. For example, nicotine intake may be increased if smokers take longer puffs, deeper puffs, more frequent puffs, or puff a greater number of times (reviewed by Scherer, 199926). Possibly, even under conditions of paced cigarette puffing and a fixed maximum number of puffs, smokers are able to compensate for nicotine loss within smoke delivery apparatus by compensatory smoking, as long as the loss to the apparatus surface area is not too great.

Since a large fraction of the surface area between the smoker and the cigarette in our original smoke delivery apparatus was located on the interior surface of the inhalation tubing, reductions in the tubing length required an in-bore installation in the rear of the magnet bore behind the participant’s head. A variety of tests were conducted to assess whether the smoke delivery apparatus might interfere with image acquisition including phantom studies using a spherical gadolinium-doped water phantom. We performed our smoking protocol scan sequence with delivery system and exhaust system in place, fan running, and using our typical cigarette lighting procedure. There was no observable image distortion caused by the presence of the device, and a comparison of the timecourses in an ROI in the center of the phantom showed no significant changes in noise when with smoking device condition was compared to a phantom imaged without the device in place (data not shown).

For validation of the impact of smoking behavior on scan quality, we analyzed BOLD signal change associated with flashing checker-board visual stimulation. These data were collected in the same experiment that produced the motion parameters depicted in Figure 4. A strong activation in primary visual cortex was observed as expected. No differences in activation were noted when average BOLD signal timecourses from each epoch were compared. These results are consistent with the idea that our improved smoke delivery apparatus does not interfere with BOLD data acquisitions, and furthermore are consistent with the hypothesis that nicotine does not affect global blood flow or neurovascular coupling in visual cortex, however, additional analysis of experimental data from more subjects is required.

The new smoke delivery device component performed well in a variety of chemical, biological and behavioral assays. A reduction in interior surface area, along with an in-bore installation appears to have improved drug delivery. The increase in nicotine levels in human plasma produced by smoking tobacco cigarettes through the device are statistically the same as the increase in nicotine delivery produced by smoking cigarettes by hand in the usual manner. Furthermore, neither the device nor the act of smoking produced detectable effects on fMRI images acquired with the device installed and in use. Although drugs other than nicotine have not been rigorously evaluated using the new smoke delivery system, this apparatus may be useful in imaging studies of other smoked drugs.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the following NIDA Grants: DA 14013 (BBF), DA003994 (SEL), DA019238 (SEL), DA021231(KPL), and DA021730 (KPL).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST

K. P. Lindsey, S. E. Lukas, R. R. Maclean, E. T. Ryan, K. R. Reed and B. deB. Frederick have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

References

- 1.Breiter HC, Gollub RL, Weisskoff RM, et al. Acute effects of cocaine on human brain activity and emotion. Neuron. 1997;19(3):591–611. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gollub RL, Breiter HC, Kantor H, et al. Cocaine decreases cortical cerebral blood flow but does not obscure regional activation in functional magnetic resonance imaging in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18(7):724–734. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kufahl P, Li Z, Risinger R, et al. Expectation modulates human brain responses to acute cocaine: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Bioi Psychiatry. 2008;63(2):222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kufahl PR, Li Z, Risinger RC, et al. Neural responses to acute cocaine administration in the human brain detected by fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;28(4):904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyer S, Kosel M, Altrichter S, et al. Pattern of regional cerebral blood-flow changes induced by acute heroin administration—a perfusion MRI study. J Neuroradiol. 2007;34(5):322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sell LA, Simmons A, Lemrnens GM, Williams SC, Brammer M, Strang J. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of the acute effect of intravenous heroin administration on visual activation in long-term heroin addicts: results from a feasibility study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;49(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobsen LK, Gore JC, Skudlarski P, Lacadie CM, Jatlow P, Krystal JH. Impact of intravenous nicotine on BOLD signal response to photic stimulation. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20(2):141–145. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein EA, Pankiewicz J, Harsch HH, et al. Nicotine-induced limbic cortical activation in the human brain: a functional MRI study. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(8):1009–1015. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ma Y, et al. Expectation enhances the regional brain metabolic and the reinforcing effects of stimulants in cocaine abusers. J Neurosci. 2003;23(36):11461–11468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11461.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBride D, Barrett SP, Kelly JT, Aw A, Dagher A. Effects of expectancy and abstinence on the neural response to smoking cues in cigarette smokers: an fMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(12):2728–2738. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose JE, Behm FM, Westman EC, et al. PET studies of the influences of nicotine on neural systems in cigarette smokers. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Feb;160(2):323–333. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frederick B, Lindsey KP, Nickerson LD, Ryan ET, Lukas SE. An MR-compatible device for delivering smoked marijuana during functional imaging. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87(1):81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolrich MW, Ripley BD, Brady M, Smith SM. Temporal autocorrelation in univariate linear modeling of FMRI data. Neuroimage. 2001;14(6):1370–1386. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Worsley KJ. Statistical analysis of activation images. In: Jezzard P, Matthews PM, Smith SM, editors. Functional MRI: An Introduction to Methods. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson SJ, Sayette MA, Delgado MR, Fiez JA. Effect of smoking opportunity on responses to monetary gain and loss in the caudate nucleus. J Abnorm Psycho I. 2008;117(2):428–434. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franklin TR, Wang Z, Wang J, et al. Limbic activation to cigarette smoking cues independent of nicotine withdrawal: a perfusion fMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(11):2301–2309. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Mendrek A, Cohen MS, et al. Effects of acute smoking on brain activity vary with abstinence in smokers performing the N-Back task: a preliminary study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;148(2-3):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanabe J, Crowley T, Hutchison K, et al. Ventral striatal blood flow is altered by acute nicotine but not withdrawal from nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(3):627–633. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn B, Ross TJ, Yang Y, Kim I, Huestis MA, Stein EA. Nicotine enhances visuospatial attention by deactivating areas of the resting brain default network. J Neurosci. 2007;27(13):3477–3489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5129-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobsen LK, D’Souza DC, Mend WE, Pugh KR, Skudlarski P, Krystal JH. Nicotine effects on brain function and functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Bioi Psychiatry. 2004;55(8):850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence NS, Ross TJ, Stein EA. Cognitive mechanisms of nicotine on visual attention. Neuron. 2002;36(3):539–548. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobsen LK, Pugh KR, Mend WE, Gelernter J. C957T polymorphism of the dopamine D2 receptor gene modulates the effect of nicotine on working memory performance and cortical processing efficiency. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188(4):530–540. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postma P, Gray JA, Sharma T, et al. A behavioural and functional neuroimaging investigation into the effects of nicotine on sensorimotor gating in healthy subjects and persons with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184(3-4):589–599. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marijuana and Health, National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine Report. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scherer G. Smoking behaviour and compensation: a review of the literature. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;145(1):1–20. doi: 10.1007/s002130051027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]