Introduction

In the past several years, a significant body of work has been published in ATVB regarding new research in the field of vascular biology and redox signaling. We would like to highlight new publications that have enriched our understanding of redox signaling in the context of vasculopathy. While redox balance and perturbation involve a plethora of proteins and signaling molecules, the focus of recent research has involved the examination of chemically reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and the interactions with other molecules or enzymes that lead to vascular pathology.1,2 There are often a variety of downstream targets and mechanisms of cross-talk that can lead to pathologies observed in the vasculature as a result of redox imbalance. The objective of this article is to underscore the novel research in the field devoted to vascular redox physiology and disease.

Reactive oxygen species

The main sources of vascular ROS are NAD(P)H oxidase (NOX),3 mitochondrial-derived superoxide (O2−),4 uncoupled nitric oxide synthase,5 and to a lesser extent xanthine oxidase,6 cyclooxygenase,7 and myeloperoxidase.8,9 A delicate ROS balance exists within the vascular wall that can be either beneficial or deleterious, depending on the source of ROS or the mechanisms of ROS capture or quenching, and these topics have been extensively discussed in previous reviews.10,11,12 ROS-associated proteins and their expression profiles vary in depending on vessel location within the vascular tree and tissue origin. Indeed, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), endothelial cells, immune cells, and other hematopoietic cell types have vastly different expression patterns for the various ROS-related proteins. Moreover, these molecules readily change in response to stimuli and disease state.13,14,15,16,17,18,19

The balance between NOX protein expression and their role in disease is highly context and tissue-dependent. There are 4 isoforms of NOX proteins found in vasculature (NOX1, NOX2, NOX4, and NOX5), and their impact on specific disease states has been broad. Consequently, much of the recent research has focused on NOX’s 1, 2 and 4, as the expression of these proteins have been found to change because of pathology and play a causal role in disease.20,21

One major point of debate has been the role of NOX4 in vascular disease. A significant body of work indicates that NOX4 is a causative agent in vascular pathology, for example, NOX4 facilitates the progression of late stage of vasculopathies like atherosclerosis and age-related inflammation.22,23,24 Inhibiting NOX4-mediated ROS may have therapeutic implications, as demonstrated by recent findings. Administration of the small n-terminal fragment of Adrenomedullin-2 (Intermedin1–53) was found to significantly reduce both angiotensin II-induced Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) knockout and CaCl2-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm in mice. It was also shown that Intermedin1–53 reduces both NOX4 protein and mRNA in vivo, suggesting transcriptional regulation of NOX4 by the small peptide.25 Moreover, NOX4 overexpression in cultured mouse aortic VSMC’s induced changes toward a senescent phenotype with higher susceptibility to apoptosis, which in atherosclerosis was found to be harmful for plaque stability in NOX4-overexpression mice.26 Novel findings on the molecular mechanisms involved in NOX4-induced stress implicate the induction of endoplasmic reticular stress through activation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) pathway.27 NOX4, which is known to produce both hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and O2−,28 can also induce DNA damage because the higher chemical stability of H2O2 prevents rapid interaction, allowing for nuclear translocation and DNA modification.29 It should be noted that not all NOX4 bioactivity creates pathological consequences. Some research has shown a protective role for NOX4 using ApoE −/− mice and LDLR−/− mice. 30,31,32,33 Brown adipose-derived H2 O2 from NOX4 protein was shown to protect the vasculature through activation of protein kinase G (PKG),34 and adipose tissue-derived NOX4 was also shown to slow the progression of type II diabetes and inflammation in obesity.35 Taken together, more investigation in this area is necessary to elucidate the role that NOX4-produced ROS plays in accumulation of atheromatous plaque and maintenance of the structural integrity of the vascular wall.

NOX2, in contrast to NOX4, is not a constitutively active NOX isoform.36 NOX2 is more highly expressed in fibroblasts and immune cells,37 participating in recruitment of other macrophages to sites of inflammation that is beneficial during removal of infectious pathogens.38 When NOX2 was overexpressed in the endothelium, increased inflammation and infiltration of leukocytes ensued.39 NOX2 protein upregulation is often observed in infiltrating fibroblasts and leukocytes. Pharmacological inhibition of NOX2 using atorvastatin reduced thrombotic stress in the vasculature.40,41 Administration of mesenchymal stem cells resulted in reduction of NOX2 and increased matrix stability, and both NOX2 null mice and mesenchymal stem cell-treated mice showed a lower incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysm, apparently through a NOX2 downregulation-mediated pathway. 42 Because multiple cell types contribute to thrombotic stress,43 and because NOX2 seems to play a role in pathological ROS production by leukocytes and fibroblasts, identification of the mechanistic details will help to combat potential NOX2-derived ROS pathologies.

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL)-induced migration of macrophages and endothelial cells seems to be NOX-dependent. Constitutive activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (PTPN11, aka SHP-2), which are proteins required for CD36-facilitated macrophage migration, is dependent on NOX-mediated ROS production. Park, et al. established this phenomenon that oxidized LDL was dependent upon NOX-produced ROS.44 Conversely, ROS-mediated activation of CD36 in extracellular vesicles was found to inhibit migration of endothelial cells.45 While the exact role of extracellular vesicles remains to be determined, this contrasting finding for ROS in endothelial cell migration needs further investigation.

NOX1 protein has also been shown to be upregulated in similar pathological conditions to those found with NOX4 in both endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells.46,47,48 Myocyte enhancing factor-2B (MEF2B) was identified as an important transcription factor in proliferation, growth and differentiation.49,50 Another study showed that engagement of the matricellular protein thrombospondin-1 with CD47 activated NOX1,51 an important finding, given that vascular matrices contribute heavily to the progression of diseases.52 Cyclic stretch in vessels induces MEF2B, which subsequently induces NOX1, and this has been identified as a necessary pathway for cyclic stretch-induced phenotypic switching of VSMC’s to a proliferative state.53 Similarly, both NOX1 and NOX4 isoforms are upregulated by high plasma glucose concentrations. Excess NOX1 and NOX4 production of ROS led to PKC-dependent downregulation of PKG protein and mRNA, which caused blunted NO-sGC-cGMP-PKG response in vitro and in vivo.54 Interestingly, human clinical data indicates that obese, sedentary individuals have elevated ROS in the blood and NOX proteins in skeletal muscle, both of which were significantly lower in lean and active subjects. These data suggest that exercise and fat accumulation heavily contribute to the regulation of ROS in the vasculature through NOX protein expression in adjacent tissues.55

Mitochondrial-derived ROS have also been identified and studied as a major contributor to vasculopathy when ROS generation goes untempered by other cellular mechanisms. ROS production is a continual process that occurs under normophysiological conditions and is estimated to produce ROS with ~1–2% of the molecular oxygen consumed by the mitochondria.56 This production is distinct from an upregulation of NOX proteins as a response to potential pathogen or danger associated molecular patterns (P/DAMPs).57 The perivascular neutrophil microenvironment has been identified as a malleable niche, influenced by the presence of excess O2− generated from mitochondria.58 Likewise, lysophosphatidylcholine has been implicated in mitochondrial ROS production and endothelial cell activation likely due to electron leakage across mitochondrial membranes.59 Both of these conditions have been implicated in the progression of atherosclerosis through surplus mitochondrial ROS. Heart muscle produces ~95% of its ATP from oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria.60,61 The energetic need for oxygen is much higher in coronary blood vessels than in other tissues in order to accommodate myocardial oxidative metabolism demands. As a result, cardiomyocyte oxygen consumption and aerobic respiration dominate oxidative production of H2O2 in the cardiac microcirculation.62 Studies have also shown that H2O2 derived from mitochondrial O2− alters human coronary resistance artery diameter.63,64,65 Healthy mitochondrial metabolism is responsible for the turnover of damaged mitochondria, but excess mitochondrial ROS can lead to depressed respiratory capacity.66 Production of ROS in coronary arteries is coupled to myocardial metabolism and, by extension, mitochondrial respiration. In sum, these data suggest that excess mitochondrial ROS and downstream manifestations are tightly regulated and may be useful as predictors for progression of atherosclerosis and other diseases of lipid accumulation.

Other sources of excess ROS production can produce pathology with subclinical indications. For example, females have been shown to have a higher incidence of vascular stiffness and increased levels of plasma uric acid.67,68,69,70 Pharmacological inhibition of xanthine oxidase was shown to increase vasoreactivity and reduce aortic hardening in female mice fed a western diet.71 In a similar manner, COX-2 is a responsive element to other forms of ROS and can exacerbate hypertension through feed-forward chronic production of inflammatory or vasoconstrictive prostaglandin synthesis and increase the magnitude of hypertension and ROS production in patients with ROS-induced vasculopathy.72

Many other ROS-sensitive mechanisms have been further elucidated, giving the field additional mechanisms and pathways to target for treatment of the most common vasculopathies. It has been established that HIF-1α expression correlates with lipid-laden plaques,73 and it has recently been demonstrated that loss of HIF-1α in mouse models of atherosclerosis reduced lesion size due to decreased macrophage recruitment and infiltration.74 It was found that HIF-1α was highly expressed in hypoxic compartments of the plaques and that HIF-1α induction associated with increased M1 differentiation. In accordance with previous findings, mice given bone marrow transplants from HIF-1α deficient mice were less likely to show the same progression of atherosclerosis.75 These results are consistent with the finding that ROS are capable of stabilizing HIF-1α.76 Another vital ROS regulatory mechanism involves Nrf2 activation.77 Indeed, reduction of Nrf2 with siRNA reduces production of antioxidant genes and proteins, promoting smooth muscle cell hyperproliferation and differentiation. This finding is consistent with the protective role for the Nrf2 pathway in atherosclerosis.78 Foam cell formation by macrophages was prevented by inhibition of the Ca2+ uptake channel Orai1, resulting in decreased lesion size, infiltration and markers of inflammation in ApoE−/− animals.79 Importantly, it was found that secretion of pro-inflammatory markers in atherosclerosis remain elevated throughout all stages, aggravating progression of the disease irrespective of foam cell senescence or proliferative capacity.80

Reactive nitrogen species

Similar to ROS, reactive nitrogen species, specifically NO and its derivatives, play vital roles in vascular function. NO is necessary for vascular tone regulation and control of blood pressure in muscular arteries throughout the vascular tree. NO signaling also participates in numerous vasculopathies, depending on the microenvironment in which it is produced and chemical reaction partners, neither of which need be mutually exclusive. As with ROS, NO generation requires tight regulation in order to avoid pathologies of insufficient or excess RNS for homeostasis.

Locale of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) expression and NO generation is an important determinant of NO fate and activity. Differential localization of endothelial NOS (eNOS) expression leads to distinct downstream responses, with apical stimulation depressing adhesion of circulating leukocytes to the vascular wall and basal stimulation resulting in higher cGMP-dependent vasodilation of blood vessels. Localization and activity of eNOS are affected by lipid enrichment and enhanced kinetic stimulation of protein kinase C-meditated phosphorylation of eNOS at S1177.81,82 Shear stress-induced PKC-mediated phosphorylation of endothelial eNOS at S1177 is also affected by glycolysis-dependent purine signaling and autophagy,83 indicating that eNOS stimulation occurs via multiple mechanisms. Where eNOS and vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) – a PKG target – have been genetically deleted in mice, inflammatory cytokines, monocyte adhesion and macrophage infiltration have been observed in adipose tissue.84,85 Indeed, the regulation of intimal proliferation through downregulation of M1-macrophage markers like matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13, is a major function of NO.86 Novel research using cross-transplanted eNOS knockout chimeras to investigate the role of eNOS in circulating blood cells established that hematopoetic cells are an important source of circulating NO within the blood.87 A specific role for erythrocyte eNOS seems to be important for the regulation of nitrite homeostasis and systemic blood pressure.

Homeostatic regulation of NO production and signaling is of widespread importance to normophysiological processes. As with ROS, excess NO production can have harmful effects on the vasculature. In both transgenic mice overexpressing eNOS and endothelium-specific caveolin-1 (cav-1) knockout mice, excess NO production promotes cardiovascular imbalance.88 Genetic deficiency of cav-1 induces cardiac hypertrophy, and overexpression of eNOS results in hypotension, which is a similar result to sepsis-associated hyper-production of NO by iNOS.89,90 Additional research has shown that excess NO, often due to inducible NOS (iNOS) leads to loss of endothelial integrity in diseases like atherosclerosis,91 despite the fact that exercise was shown to promote healthy arteriogenesis in an iNOS-dependent manner.92

Recent studies have focused on identifying mechanisms of NO inactivation by pathological O2− generation. It was shown that perivascular adipose tissue of obese mice promotes uncoupling of eNOS, converting the protein to a O2− generator that exacerbates the underlying pathology.93,94,95 Similar findings were reported in obese mice fed a high fat diet, wherein cardiovascular dysfunction associated with NO deficiency driven by perivascular adiposity which was reversed by L-arginine supplementation and arginase inhibitor treatment therapies.96

A new area of research has focused on hemoproteins in endothelium and VSMC’s and how heme oxidation state (ferric (Fe3+) versus ferrous (Fe2+)) modulate NO signaling. It was shown that the redox state of hemoglobin α (Hbα) at the myoendothelial junction (MEJ) regulates NO signaling. When in the Fe3+ state, Hbα has a reduced binding affinity for NO, allowing the gaseous molecule to diffuse between the endothelium and the VSMC. By contrast, when Hbα is in the reduced Fe2+ state, NO is intercepted and signaling between endothelium and smooth muscle cells types is blunted, decreasing NO-sGC-cGMP-mediated vasodilation.97,98,99 Studies have demonstrated that disruption of Hbα coupling to eNOS with a Hbα-mimetic peptide enhanced NO-sGC-cGMP-dependent dilation of resistance arteries in both the systemic and pulmonary circuits.100,101 In endothelial cells, pharmacological inhibition of flavoprotein NADH cytochrome B5 reductase 3 (Cyb5R3), otherwise known as methemoglobin reductase, facilitates NO signaling via the MEJ.102,103 In VSMC’s, a recent study showed a new role of Cyb5R3 where it functions to reduce sGC from its Fe3+ to its Fe2+ state. This reduction of the sGC heme iron allows for NO sensing needed for cGMP production and dilation of arteries. Indeed, this finding represents the first insight into an enzymatic mechanism for regulating heme iron redox state of sGC.104 Innovative research using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) techniques has allowed for visualization of cGMP movement in real-time, revealing that not only is the breakdown of cGMP by phosphodiesterase (PDE) isoforms 3 and 5 important, but cellular export of cGMP plays an important role as well.105

Conclusions

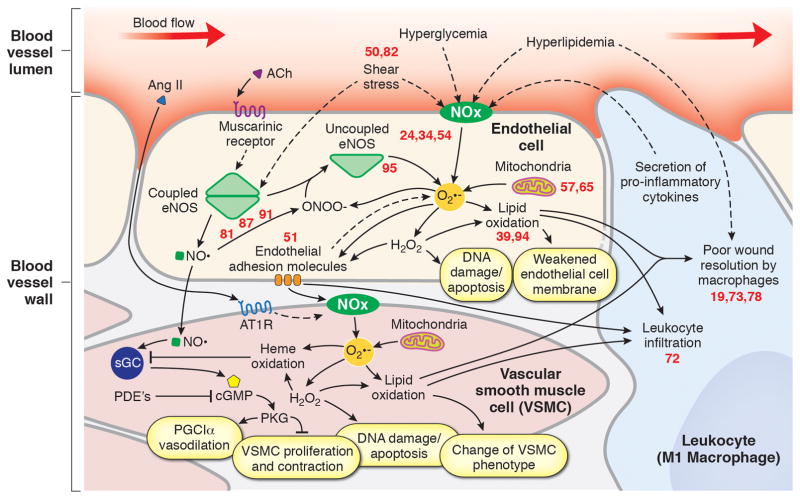

When taken together, these new studies have led to valuable insight emphasizing the importance of redox equilibrium needed for vascular health and how an imbalance promotes cardiovascular pathology (Figure. 1). As the field leverages new techniques to measure the kinetics of production and quantitate the amount of ROS/RNS needed for basic cell signaling, the nuances of this relationship will become clearer. Finally, as new discoveries surface, emphasis should be placed on developing innovative strategies to therapeutically target redox imbalance in cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1.

Numbers correspond to a reference in the bibliography from recent literature published in ATVB that has added to this area of the field and aided in our understanding of this pathway. Ach indicates acetylcholine; AngII, angiotensin II; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NOx, NAD(P)H oxidase; O2−, superoxide; NO., nitric oxide; AT1R, angiotensin II receptor type 1; sGC, soluble guanylate cyclase; PDE, phosphodiesterase; cGMP, 3′,5′-cyclic-guanosine monophosphate; PGC1α, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL 133864, R01 HL 128304, AHA Grant-in-Aid 16GRNT27250146 (ACS) and NIH T32 AG021885 (J.C.G). This work was also supported by the Institute for Transfusion Medicine and the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania (Straub). We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Katherine Wood, Brittany Durgin, Scott Hahn, Megan Miller, Subramaniam Sanker, Rohan Shah, and Nolan Carew for their aid in critical analysis of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Bibliography

- 1.Nowak WN, Deng J, Ruan XZ, Xu Q. Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;37(5):e41–e52. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirst DG, Robson T. Nitric Oxide Physiology and Pathology. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;704:1–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-964-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nri1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadenas E, Boveris A, Ragan CI, Stoppani AO. Production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide by NADH-ubiquinone reductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from beef-heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;180:248–257. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia Y, Tsai AL, Berka V, Zweier JL. Superoxide generation from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase: A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent and tetrahydrobiopterin regulatory process. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25804–25808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley EE, Khoo NKH, Hundley NJ, Malik UZ, Freeman BA, Tarpey MM. Hydrogen Peroxide is the Major Oxidant Product of Xanthine Oxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48(4):493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Retailleau K, Belin de Chantemele EJ, Chanoine S, Guihot AL, Vessières E, Toutain B, Faure S, Bagi Z, Loufrani L, Henrion D. Reactive oxygen species and cyclooxygenase 2-derived thromboxane A2 reduce angiotensin II type 2 receptor vasorelaxation in diabetic rat resistance arteries. Hypertension. 2009;55:339–344. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholls SJ, Hazen SL. Myeloperoxidase and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1102–1111. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000163262.83456.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klebanoff SJ. Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe. J Leuk Biol. 2005;77(5):598–625. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra V, Shah C, Mokashe N, Chavan R, Yadav H, Prajapati J. Probiotics as potential antioxidants: A systematic review. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63(14):3615–3626. doi: 10.1021/jf506326t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sindhia V, Gupta V, Sharma K, Bhatnagar S, Kumari R, Dhaka N. Potential applications of antioxidants – A review. J Pharm Res. 2013;7(9):828–835. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carocho M, Ferreira ICFR. A review on antioxidants, prooxidants and related controversy: Natural and synthetic compounds, screening and analysis methodologies and future perspectives. Food and Chem Toxicol. 2013;51:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause KH. Tissue distribution and putative physiological function of NOX family NADPH oxidases. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57(5):S28–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lassegue B, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases: functions and pathologies in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:653–661. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kratofil RM, Kubes P, Deniset JF. Monocyte Conversion During Inflammation and Injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(1):35–42. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasterkamp G, van der Laan SW, Haitjema S, Asl HF, Siemelink MA, Bezemer T, van Setten J, Dichgans M, Malik R, Worrall BB, Schunkert H, Samani NJ, de Kleijn DPV, Markus HS, Hoefer IE, Michoel T, de Jager SCA, Björkegren JLM, den Ruijter HM, Asselbergs FW. Human validation of genes associated with a murine atherosclerotic phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1240–1246. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reglero-Real N, Colom B, Bodkin JV, Nourshargh S. Endothelial Cell Junctional Adhesion Molecules: Role and Regulation of Expression in Inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(10):2048–2057. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin K, You Y, Swier V, Tang L, Radwan MM, Pandya AN, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D protects against atherosclerosis via regulation of cholesterol efflux and macrophage polarization in hypercholesterolemic swine. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2432–2442. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korytowski W, Wawak K, Pabisz P, Schmitt JC, Chadwick AC, Sahoo D, Girotti AW. Impairment of Macrophage Cholesterol Efflux by Cholesterol Hydroperoxide Trafficking: Implications for Atherogenesis Under Oxidative Stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(10):2104–2113. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassegue B, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases: functions and pathologies in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:653–661. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181610. [REPEAT] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambeth JD. Nox Enzymes, ROS, and Chronic Disease: An Example of Antagonistic Pleiotropy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43(3):332–347. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vendrov AE, Vendrov, Smith A, Yuan J, Sumida A, Robidoux J, Runge MS, Madamanchi NR. NOX4 NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Aging-Associated Cardiovascular Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;23(18):1389–1409. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lozhkin A, Vendrov AE, Pan H, Wickline SA, Madamanchi NR, Runge MS. NADPH oxidase 4 regulates vascular inflammation in aging and atherosclerosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;102:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barman SA, Chen F, Su Y, Dimitropoulou C, Wang Y, Catravas JD, Han W, Orfi L, Szantai-Kis C, Keri G, Szabadkai I, Barabutis N, Rafikova O, Rafikov R, Black SM, Jonigk D, Giannis A, Asmis R, Stepp DW, Ramesh G, Fulton DJ. NADPH oxidase 4 is expressed in pulmonary artery adventitia and contributes to hypertensive vascular remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(8):1704–15. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu WW, Jia LX, Ni XQ, Zhao L, Chang JR, Zhang JS, Hou YL, Zhu Y, Guan YF, Yu YR, Du J, Tang CS, Qi YF. Intermedin1–53 attenuates abdominal aortic aneurysm by inhibiting oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2176–2190. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu S, Chamseddine AH, Carrell S, Miller FJ., Jr Nox4 NADPH oxidase contributes to smooth muscle cell phenotypes associated with unstable atherosclerotic plaques. Redox Biology. 2014;2:642–650. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos CX, Hafstad AD, Beretta M, Zhang M, Molenaar C, Kopec J, Fotinou D, Murray TV, Cobb AM, Martin D, Zeh Silva M, Anilkumar N, Schröder K, Shanahan CM, Brewer AC, Brandes RP, Blanc E, Parsons M, Belousov V, Cammack R, Hider RC, Steiner RA, Shah AM. Targeted redox inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 by Nox4 regulates eIF2α-mediated stress signaling. EMBO J. 2016;35(3):319–334. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nisimoto Y, Diebold BA, Cosentino-Gomes D, Lambeth JD. Nox4: a hydrogen peroxide-generating oxygen sensor. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5111–5120. doi: 10.1021/bi500331y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weyemi U, Dupuy C. The emerging role of ROS-generating NADPH oxidase NOX4 in DNA-damage responses. Mutat Res. 2012;751(2):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray SP, Di Marco E, Kennedy K, Chew P, Okabe J, El-Osta A, Calkin AC, Biessen EA, Touyz RM, Cooper ME, Schmidt HH, Jandeleit-Dahm KA. Reactive oxygen species can provide atheroprotection via NOX4-dependent inhibition of inflammation and vascular remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:295–307. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.307012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schürmann C, Rezende F, Kruse C, Yasar Y, Löwe O, Fork C, van de Sluis B, Bremer R, Weissmann N, Shah AM, Jo H, Brandes RP, Schröder K. The NADPH oxidase Nox4 has anti-atherosclerotic functions. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(48):3447–56. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craige SM, Kant S, Reif M, Chen K, Pei Y, Angoff R, Sugamura K, Fitzgibbons T, Keaney JF., Jr Endothelial NADPH oxidase 4 protects ApoE−/− mice from atherosclerotic lesions. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;89:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langbein H, Brunssen C, Hofmann A, Cimalla P, Brux M, Bornstein SR, Deussen A, Koch E, Morawietz H. NADPH oxidase 4 protects against development of endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in LDL receptor deficient mice. Eur Heart J. 2015;37:1753–1761. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friederich-Persson M, Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Persson P, Montezano AC, Touyz RM. Brown adipose tissue regulates small artery function through NADPH oxidase 4-derived hydrogen peroxide and redox-sensitive protein kinase G-1α. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(3):455–465. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Den Hartigh LJ, Omer M, Goodspeed L, Wang S, Wietecha T, O’Brien KD, Han CY. Adipocyte-specific deficiency of NADPH oxidase 4 delays the onset of insulin resistance and attenuates adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(3):466–475. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nisimoto Y, Jackson HM, Ogawa H, Kawahara T, Lambeth JD. Constitutive NADPH-dependent electron transferase activity of the nox4 dehydrogenase domain. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2433–2442. doi: 10.1021/bi9022285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.NADPH oxidases: an overview from structure to innate immunity-associated pathologies. Cell & Molec Immunol. 2015;12:5–23. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kovács I, Horváth M, Lányi Á, Petheő GL, Geiszt M. Reactive oxygen species-mediated bacterial killing by B lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;97(6):1133–1137. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4AB1113-607RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douglas G, Bendall JK, Crabtree MJ, Tatham AL, Carter EE, Hale AB, Channon KM. Endothelial-specific Nox2 overexpression increases vascular superoxide and macrophage recruitment in ApoE−/− mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94(1):20–29. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Violi F, Carnevale R, Loffredo L, Pignatelli P, Gallin JI. NADPH oxidase-2 and atherothrombosis: insight from chronic granulomatous disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:218–225. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pignatelli P, Carnevale R, Pastori D, Cangemi R, Napoleone L, Bartimoccia S, Novella C, Basili S, Violi F. Immediate antioxidant and antiplatelet effect of atorvastatin via inhibition of Nox2. Circulation. 2012;126:92–103. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.095554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma AK, Salmon MD, Lu G, Su G, Pope NH, Smith JR, Weiss ML, Upchurch GR., Jr Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate NADPH oxidase-dependent high mobility group box 1 production and inhibit abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:908–918. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizvi M1, Pathak D, Freedman JE, Chakrabarti S. CD40–CD40 ligand interactions in oxidative stress, inflammation and vascular disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(12):530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park YM, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL. CD36 modulates migration of mouse and human macrophages in response to oxidized LDL and may contribute to macrophage trapping in the arterial intima. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:136–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI35535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramakrishnan DP, Hajj-Ali RA, Chen Y, Silverstein RL. Extracellular Vesicles Activate a CD36-Dependent Signaling Pathway to Inhibit Microvascular Endothelial Cell Migration and Tube Formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(3):534–544. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.307085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1994;74:1141–1148. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szöcs K, Lassègue B, Sorescu D, Hilenski LL, Valppu L, Couse TL, Wilcox JN, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Upregulation of nox-based NAD(P)H oxidases in restenosis after carotid injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:21–27. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.102189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang J, Saha A, Boo YC, Sorescu GP, McNally JS, Holland SM, Dikalov S, Giddens DP, Griendling KK, Harrison DG, Jo H. Oscillatory Shear Stress Stimulates Endothelial Production of Formula from p47phox-dependent NAD(P)H Oxidases, Leading to Monocyte Adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(47):47291–47298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katoh Y, Molkentin JD, Dave V, Olson EN, Periasamy M. MEF2B is a component of a smooth muscle-specific complex that binds an A/T-rich element important for smooth muscle myosin heavy chain gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1511–1518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Potthoff MJ, Olson EN. MEF2: a central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development. 2007;134:4131–4140. doi: 10.1242/dev.008367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Csányi G, Yao M, Rodriguez AI, Al Ghouleh I, Sharifi-Sanjani M, Frazziano G, Xiaojun H, Kelley EE, Isenberg JS, Pagano PJ. Thrombospondin-1 Regulates Blood Flow via CD47 Receptor-Mediated Activation of NADPH Oxidase 1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2966–2973. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kick K, Nekolla K, Rehberg M, Vollmar AM, Zahler S. New view on endothelial cell migration: switching modes of migration based on matrix composition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2346–2357. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodríguez AI, Csányi G, Ranayhossaini DJ, Feck DM, Blose KJ, Assatourian L, Vorp DA, Pagano PJ. MEF2B-Nox1 signaling is critical for stretch-induced phenotypic modulation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:430–438. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu S, Ma X, Gong M, Shi L, Lincoln T, Wang S. Glucose down-regulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I expression in vascular smooth muscle cells involves NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:852–863. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.La Favor JD, Dubis GS, Yan H, White JD, Nelson MA, Anderson EJ, Hickner RC. Microvascular endothelial dysfunction in sedentary, obese humans is mediated by NADPH oxidase: influence of exercise training. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(12):2412–2420. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J. 1973;134(3):707–16. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kovács I, Horváth M, Lányi Á, Petheő GL, Geiszt M. Reactive oxygen species-mediated bacterial killing by B lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;97(6):1133–1137. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4AB1113-607RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y, Wang W, Wang N, Tall AR, Tabas I. Mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes atherosclerosis and neutrophil extracellular traps in aged mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(8):e99–e107. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li X, Fang P, Li Y, Kuo YM, Andrews AJ, Nanayakkara G, Johnson C, Fu H, Shan H, Du F, Hoffman NE, Yu D, Eguchi S, Madesh M, Koch WJ, Sun J, Jiang X, Wang H, Yang X. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Mediate Lysophosphatidylcholine-Induced Endothelial Cell Activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(6):1090–1100. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Opie LH. Metabolism of the heart in health and disease. I. Am Heart J. 1968;76:685–698. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(68)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Opie LH. Metabolism of the heart in health and disease. II. Am Heart J. 1969;77:100–122. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(69)90135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saitoh S, Zhang C, Tune JD, Potter B, Kiyooka T, Rogers PA, Knudson JD, Dick GM, Swafford A, Chilian WM. Hydrogen peroxide: a feed-forward dilator that couples myocardial metabolism to coronary blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2614–2621. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000249408.55796.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y, Zhao H, Li H, Kalyanaraman B, Nicolosi AC, Gutterman DD. Mitochondrial sources of H2O2 generation play a key role in flow-mediated dilation in human coronary resistance arteries. Circ Res. 2003;93:573–580. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091261.19387.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Archer SL, Huang JMC, Reeve HL, Hampl V, Tolarova S, Michelakis E, Weirnik PH. Differential distribution of electrophysiologically distinct myocytes in conduit and resistance arteries determines their response to nitric oxide and hypoxia. Circ Res. 1996;78:431–442. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miura H, Bosnjak JJ, Ning G, Saito T, Miura M, Gutterman DD. Role for hydrogen peroxide in flow-induced dilation of human coronary arterioles. Circ Res. 2003;92:e31–e40. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000054200.44505.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Song M, Chen Y, Gong G, Murphy E, Rabinovitch PS, Dorn GW., 2nd Super-suppression of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species signaling impairs compensatory autophagy in primary mitophagic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2014 Jul 18;115(3):348–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park JS, Nam JS, Cho MH, Yoo JS, Ahn CW, Jee SH, Lee HS, Cha BS, Kim KR, Lee HC. Insulin resistance independently influences arterial stiffness in normoglycemic normotensive postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17:779–784. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181cd3d60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shapiro Y, Mashavi M, Luckish E, Shargorodsky M. Diabetes and menopause aggravate age-dependent deterioration in arterial stiffness. Menopause. 2014;21:1234–1238. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fang JI, Wu JS, Yang YC, Wang RH, Lu FH, Chang CJ. High uric acid level associated with increased arterial stiffness in apparently healthy women. Atherosclerosis. 2014;236:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nogi S, Fujita S, Okamoto Y, Kizawa S, Morita H, Ito T, Sakane K, Sohmiya K, Hoshiga M, Ishizaka N. Serum uric acid is associated with cardiac diastolic dysfunction among women with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H986–H99. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00402.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lastra G, Manrique C, Jia G, Aroor AR, Hayden MR, Barron BJ, Niles B, Padilla J, Sowers JR. Xanthine oxidase inhibition protects against Western diet-induced aortic stiffness and impaired vasorelaxation in female mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2017;313(2):R67–R77. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00483.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martinez-Revelles S, Avendano MS, Garcia-Redondo AB, Alvarez Y, Aguado A, Perez-Giron JV, Garcia-Redondo L, Esteban V, Redondo JM, Alonso MJ, Briones AM, Salaices M. Reciprocal relationship between reactive oxygen species and cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(1):51–65. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vink A, Schoneveld AH, Lamers D, Houben AJ, van der Groep P, van Diest PJ, Pasterkamp G. HIF-1 alpha expression is associated with an atheromatous inflammatory plaque phenotype and upregulated in activated macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195(2):e69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Korytowski W, Wawak K, Pabisz P, Schmitt JC, Chadwick AC, Sahoo D, Girotti AW. Endothelial Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Promotes Atherosclerosis and Monocyte Recruitment by Upregulating MicroRNA-19a. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(10):2104–2113. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aarup A, Pedersen TX, Junker N, Christoffersen C, Bartels ED, Madsen M, Nielsen CH, Nielsen LB. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression in macrophages promotes development of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1782–1790. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Movafagh S, Crook S, Vo K. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a by reactive oxygen species: new developments in an old debate. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116:696–703. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kobayashi EH, Suzuki T, Funayama R, Nagashima T, Hayashi M, Sekine H, Tanaka N, Moriguchi T, Motohashi H, Nakayama K, Yamamoto M. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11624. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ashino T, Yamamoto M, Yoshida T, Numazawa S. Redox-sensitive transcription factor Nrf2 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell migration and neointimal hyperplasia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:760–768. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liang SJ, Zeng DY, Mai XY, Shang JY, Wu QQ, Yuan JN, Yu BX, Zhou P, Zhang FR, Liu YY, Lv XF, Liu J, Ou JS, Qian JS, Zhou JG. Inhibition of Orai1 Store-Operated Calcium Channel Prevents Foam Cell Formation and Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(4):618–628. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Childs BG, Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Conover CA, Campisi J, van Deursen JM. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science. 2016 Oct 28;354(6311):472–477. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Biwera LA, Taddeoc EP, Kenwood BM, Hoehn KL, Straub AC, Isakson BE. Two functionally distinct pools of eNOS in endothelium are facilitated by myoendothelial junction lipid composition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861(7):671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Denimal D, Monier S, Brindisi MC, Petit JM, Bouillet B, Nguyen A, Demizieux L, Simoneau I, Pais de Barros JP, Vergès B, Duvillard L. Impairment of the ability of HDL from patients with metabolic syndrome but without diabetes mellitus to activate eNOS: correction by S1P enrichment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(5):804–811. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bharath LP, Cho JM, Park SK, Ruan T, Li Y, Mueller R, Bean T, Reese V, Richardson RS, Cai J, Sargsyan A, Pires K, Anandh Babu PV, Boudina S, Graham TE, Symons JD. Endothelial cell autophagy maintains shear stress-induced nitric oxide generation via glycolysis-dependent purinergic signaling to endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(9):1646–1656. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rizzo NO1, Maloney E, Pham M, Luttrell I, Wessells H, Tateya S, Daum G, Handa P, Schwartz MW, Kim F. Reduced NO-cGMP signaling contributes to vascular inflammation and insulin resistance induced by high-fat feeding. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(4):758–765. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.199893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen L1, Daum G, Chitaley K, Coats SA, Bowen-Pope DF, Eigenthaler M, Thumati NR, Walter U, Clowes AW. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein regulates proliferation and growth inhibition by nitric oxide in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004 Aug;24(8):1403–1408. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134705.39654.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lavin B, Gómez M, Pello OM, Castejon B, Piedras MJ, Saura M, Zaragoza C. Nitric oxide prevents aortic neointimal hyperplasia by controlling macrophage polarization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(8):1739–46. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wood KC, Cortese-Krott MM, Kovacic JC, Noguchi A, Liu VB, Wang X, Raghavachari N, Boehm M, Kato GJ, Kelm M, Gladwin MT. Circulataing blood endothelial nitric oxide synthase contributes to the regulation of systemic blood pressure and nitrite homeostasis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(8):1861–71. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.301068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Godo S, Sawada A, Saito H, Ikeda S, Enkhjargal B, Suzuki K, Tanaka S, Shimokawa H. Disruption of physiological balance between nitric oxide and endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization impairs cardiovascular homeostasis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(1):97–107. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lambden S, Kelly P, Ahmetaj-Shala B, Wang Z, Lee B, Nandi M, Torondel B, Delahaye M, Dowsett L, Piper S, Tomlinson J, Caplin B, Colman L, Boruc O, Slaviero A, Zhao L, Oliver E, Khadayate S, Singer M, Arrigoni F, Leiper J. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 regulates nitric oxide synthesis and hemodynamics and determines outcome in polymicrobial sepsis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(6):1382–1392. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Reventun P, Alique M, Cuadrado I, Márquez S, Toro R, Zaragoza C, Saura M. iNOS-derived nitric oxide induces integrin-linked kinase endocytic lysosome-mediated degradation in the vascular endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(7):1272–1281. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schirmer SH, Millenaar DN, Werner C, Schuh L, Degen A, Bettink SI, Lipp P, van Rooijen N, Meyer T, Böhm M, Laufs U. Exercise promotes collateral artery growth mediated by monocytic nitric oxide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(8):1862–1871. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang HD, Pagano PJ, Du Y, Cayatte AJ, Quinn MT, Brecher P, Cohen RA. Superoxide anion from the adventitia of the rat thoracic aorta inactivates nitric oxide. Circ Res. 1998;82(7):810–818. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.7.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen W, Druhan LJ, Chen CA, Hemann C, Chen YR, Berka V, Tsai AL, Zweier JL. Peroxynitrite induces destruction of the tetrahydrobiopterin and heme in endothelial nitric oxide synthase: transition from reversible to irreversible enzyme inhibition. Biochemistry. 2010;49(14):3129–37. doi: 10.1021/bi9016632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kamstrup PR, Hung MY, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Nordestgaard BG. Oxidized phospholipids and risk of calcific aortic valve disease: the copenhagen general population study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(8):1570–1578. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xia N, Horke S, Habermeier A, Closs EI, Reifenberg G, Gericke A, Mikhed Y, Münzel T, Daiber A, Förstermann U, Li H. Uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in perivascular adipose tissue of diet-induced obese mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:78–85. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Straub AC, Lohman AW, Billaud M, Johnstone SR, Dwyer ST, Lee MY, Bortz PS, Best AK, Columbus L, Gaston B, Isakson BE. Endothelial cell expression of haemoglobin α regulates nitric oxide signalling. Nature. 2012;491(7424):473–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Straub AC, Butcher JT, Billaud M, Mutchler SM, Artamonov MV, Nguyen AT, Johnson T, Best AK, Miller MP, Palmer LA, Columbus L, Somlyo AV, Le TH, Isakson BE. Hemoglobin α/eNOS coupling at myoendothelial junctions is required for nitric oxide scavenging during vasoconstriction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(12):2594–2600. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alvarez RA, Miller MP, Hahn SA, Galley JC, Bauer E, Bachman T, Hu J, Sembrat J, Goncharov D, Mora AL, Rojas M, Goncharova E, Straub AC. Targeting pulmonary endothelial hemoglobin α improves nitric oxide signaling and reverses pulmonary artery endothelial dysfunction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017 Aug 11; doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0418OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Straub AC, Butcher JT, Billaud M, Mutchler SM, Artamonov MV, Nguyen AT, Johnson T, Best AK, Miller MP, Palmer LA, Columbus L, Somlyo AV, Le TH, Isakson BE. Hemoglobin α/eNOS coupling at myoendothelial junctions is required for nitric oxide scavenging during vasoconstriction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(12):2594–2600. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303974. [REPEAT] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Alvarez RA, Miller MP, Hahn SA, Galley JC, Bauer E, Bachman T, Hu J, Sembrat J, Goncharov D, Mora AL, Rojas M, Goncharova E, Straub AC. Targeting pulmonary endothelial hemoglobin α improves nitric oxide signaling and reverses pulmonary artery endothelial dysfunction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017 Aug 11; doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0418OC. [REPEAT] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Straub AC, Lohman AW, Billaud M, Johnstone SR, Dwyer ST, Lee MY, Bortz PS, Best AK, Columbus L, Gaston B, Isakson BE. Endothelial cell expression of haemoglobin α regulates nitric oxide signalling. Nature. 2012;491(7424):473–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11626. [REPEAT] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rahaman MM, Reinders FG, Koes D, Nguyen AT, Mutchler SM, Sparacino-Watkins C, Alvarez RA, Miller MP, Cheng D, Chen BB, Jackson EK, Camacho CJ, Straub AC. Structure guided chemical modifications of propylthiouracil reveal novel small molecule inhibitors of cytochrome b5 reductase that increase nitric oxide bioavailability. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(27):16861–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.629964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rahaman MM, Nguyen AT, Miller MP, Hahn SA, Sparacino-Watkins C, Jobbagy S, Carew NT, Cantu-Medellin N, Wood KC, Baty C, Schopfer FJ, Kelley EE, Gladwin MT, Martin E, Straub AC. Cytochrome b5 reductase 3 modulates soluble guanylate cyclase redox state and cGMP signaling. Circ Res. 2017;121(2):137–148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Krawutschke C, Koesling D, Russwurm M. Cyclic GMP in Vascular Relaxation: Export Is of Similar Importance as Degradation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(9):2011–2019. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]