Abstract

Background

Myricetin has been shown to possess potential antiangiogenic effects in endothelial cells. However, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Therefore, we evaluated its antiangiogenic effects in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs).

Methods

HUVECs were cultured in endothelial cell growth medium-2 to induce proliferation and angiogenesis and treated with different doses of myricetin (0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) for 24 hours. Cell proliferation was analyzed by the MTT and lactate dehydrogenase release assays; angiogenesis was determined by the tube formation assay. In addition, cell signaling pathways related to angiogenesis were investigated by Western blotting.

Results

Myricetin induced apoptosis and procaspase-3 cleavage though the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS). It significantly inhibited cell migration, tube formation, and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in HUVECs.

Conclusions

Myricetin exerts antiangiogenic effects by inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis and inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in HUVECs.

Keywords: Myricetin, Apoptosis, Angiogenesis, Human umbilical vascular endothelial cells

INTRODUCTION

Angiogenesis is a physiological process through which new blood vessels are formed preexisting vessels.1 The inhibition of vascular formation holds promising anticancer potential.2,3 Therefore, studies to elucidate the mechanisms of angiogenesis in cancer and identify novel antiangiogenic agents are warranted.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulate angiogenesis; high levels of ROS can lead to oxidative cell damage and apoptosis.4 However, low levels of ROS promote endothelial cell growth, migration, and organization into tubular network structures, thereby driving angiogenesis.5 ROS-induced oxidative stress is considered an intrinsic death stimulus for the direct or indirect activation of the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.6 The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is important for signaling in normal cells, but is also implicated in the development of various cancers. This pathway regulates cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, invasion, metabolism, differentiation, apoptosis, and survival.7,8 Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate activates serine/threo-nine kinases, such as 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) and Akt. Phosphatase and tensin homolog encodes a phosphatase that opposes the action of PI3K and reduces the level of activated Akt, which controls protein synthesis and cell growth by stimulating the phosphorylation of mTOR.9 PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling proteins are reported to arrest cell growth and induce apoptosis via ROS generation.10

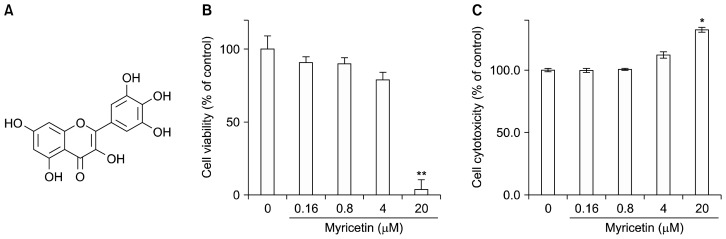

Natural phytochemicals are reported to possess significant therapeutic potential with negligible side effects.11,12 Polyphenols constitute an important class of natural bioactive compounds that are abundant in different plant species. Flavonoids are a type of polyphenols that are present in many different fruits and vegetables. They exert anticancer activities through their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic, anti-proliferative, and apoptotic actions.13–18 Myricetin has a quercetin backbone with an additional hydroxyl group (Fig. 1A). It is the major flavonoid found in onions, berries, and grapes.19–21 Its antioxidant, cytoprotective, antiviral, antimicrobial, antiplatelet, and anticancer activities have been reported.22–24 It significantly inhibits angiogenesis in vascular endothelial growth factor-stimulated human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs).25 However, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood.

Figure 1.

Inhibitory effect of myricetin on the growth of human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). (A) Chemical structure of myricetin. After HUVECs were cultured with myricetin (0.16, 0.8, 4, and 20 μM) for 24 hours, (B) cell viability and (C) cytotoxicity were assessed by the MTT and lactate dehydrogenase release assays, respectively. Results are expressed as the percentage of control cells cultured in the absence of myricetin and reported as the mean ± SD of three separate experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with control.

We evaluated whether myricetin suppresses angiogenesis through the induction of ROS-mediated apoptosis and the inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in HUVECs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Reagents

Myricetin (Fig. 1A) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The compound was dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A 100 mmol/L stock solution of myricetin was prepared and stored as small aliquots at −20°C until needed. We purchased MTT, DMSO, gelatin, and Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies from Sigma-Aldrich. Growth factor-reduced Matrigel was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). The specific antibodies against PI3K, PDK1, AKT, mTOR, and their phospho forms, anti-procaspase-3 antibody, and the AKT inhibitor LY294002 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The HRP-conjugated β-actin, p53, and Bax antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) diacetate (H2DCFDA) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

2. Endothelial cell culture

HUVECs were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured in endothelial cell growth medium-2 (EGM-2; Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. HUVECs at passages 3 to 5 were used in the experiments. The commercially available vascular endothelial cell-specific supplement EGM®-2 MV Bullet kit was used.26

3. Growth inhibition assay

The cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay. HUVECs (5 × 103 cells/well) were seeded into a 96-well plate with EGM-2 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were allowed to adhere and the culture medium was removed. The cells incubated with serum-free medium for 12 hours. After serum starvation, the cells were cultured in fresh medium supplemented with 2% FBS and various concentrations of myricetin at 37°C for 24 hours. After incubation, MTT solution was added and the reaction plate was incubated for an additional 4 hours. The resulting formazan deposit was solubilized with DMSO and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a VersaMax ELISA microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The effects of myricetin on cytotoxicity were tested by using the CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, Ma-dison, WI, USA). The viability and cytotoxicity of myricetin were calculated as a percentage relative to the solvent-treated control. The IC50 values were calculated by using a non-linear regression analysis of the percentage growth versus concentration.

4. Cell cycle analysis

HUVECs were plated in culture dishes with a 100-mm diameter and incubated. On the next day, the cells were treated with various concentrations (0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) of myricetin for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were harvested and fixed with 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. The cells were washed, stained with 50 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) and 50 μg/mL RNase A for 1 hour in the dark, and then analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of cells in each specific cell cycle phase. Flow cytometric analysis was performed by using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped with a 488 nm argon laser. The events were evaluated for each sample and the cell cycle distribution was determined by using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). The results were presented as the number of cells versus the amount of DNA, as indicated by fluorescence signal intensity. All experiments were conducted three times.

5. Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis

To determine the level of apoptosis after exposure of HUVECs to myricetin for 24 hours, an annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) apoptosis detection kit (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used. In this assay, annexin V-FITC binds to phosphatidylserine, which translocates to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during the early stages of cell apoptosis. Therefore, apoptotic cells are specifically stained with annexin V-FITC, whereas the necrotic cells were double-stained with both annexin V-FITC and PI. The cells were suspended in binding buffer at a final cell concentration of 1 × 105 cells/mL and incubated with both annexin V-FITC and PI for 25 minutes in the dark. The DNA content of the stained cells was analyzed by using CellQuest Software and a FACS Vantage SE flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

6. Quantification of reactive oxygen species production

The intracellular ROS levels were measured by using the fluorescent dye H2DCFDA. First, HUVECs were incubated with myricetin for 24 hours. The cells were then washed twice, stained with 20 μM H2DCFDA for 30 minutes, and subjected to two further washes. As H2DCFDA reacts with ROS to form the fluorescent compound DCF, the intracellular DCF intensity was measured by using a flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

7. Scratch-wound migration assay

HUVECs were allowed to grow to full confluence in 6-well plates pre-coated with 0.1% gelatin and then incubated with 10 mg/mL mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 2 hours to inactivate the HUVECs. The monolayers of HUVECs were wounded by a scratch with a 0.2-mL pipette tip. Fresh medium containing various concentrations of myricetin was added. After incubation for 24 hours, representative images were captured by using an inverted phase contrast light microscope (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) after 24 hours incubation. The migrated cells from three randomly selected fields were quantified by manual counting (DMC advanced program) under an optical microscope at 200× magnification and the inhibition was calculated as a percentage relative to the control.

8. Tube formation assay with human umbilical vascular endothelial cells on Matrigel

Matrigel (70 μL/well) was added to a 96-well plate and polymerized for 30 minutes at 37°C. The HUVECs (3 × 104 cells) were seeded onto each well of the Matrigel-coated 96-well plate and then incubated in EBM-2 supplemented with 2% FBS and various concentrations of myricetin. After incubation for 8 hours, the formation of the endothelial cell tubular structure was visualized under an inverted microscope and photographed at 40× magnification. Furthermore, tube formation was calculated from the tube length, normalized, and expressed as a percentage by normalization with untreated control cells.

9. Western blot analysis

The cells were treated with myricetin for 24 hours. Harvested cells were lysed in protein extraction solution (Intron Biotechnology, Inc., Seongnam, Korea) containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors for 10 minutes at 4°C. The total protein concentration in the supernatant was measured by using the Bradford assay. Forty microgram samples of the total proteins were heated at 95°C for 5 minutes and subjected to 6% to 15% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) at 100 V for 60 to 100 minutes. The membranes were incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS with 0.05% tween 20 (TBST) for 30 minutes at room temperature and then with primary antibodies diluted at dilutions of 1 : 200 to 1 : 1,000 in 5% BSA in TBST overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies. The protein bands were detected by using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Intron Biotechnology, Inc.) and an LAS-1000 Imager (Fuji Film Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

10. Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by using one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test for paired data. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The calculations were computed by using SPSS for Windows ver. 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

1. Effects of myricetin on endothelial cell proliferation

To determine the non-cytotoxic concentration of myricetin against HUVECs, the cells were treated with myricetin (0.16, 0.8, 4, and 20 μM) for 24 hours. Subsequently, cell viability was evaluated by the MTT (Fig. 1B) and lactate dehydrogenase release assays (Fig. 1C). We observed that concentrations above 4 μM caused cytotoxic effects. Therefore, analysis of biological activities of myricetin was conducted at concentrations lower than 4 μM in subsequent experiments. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the effects of myricetin on the cell cycle of HUVECs. After exposure to myricetin for 24 hours, the cells were harvested and analyzed for their cell cycle distribution (sub-G1, G0/G1, S, and G2/M). Myricetin increased the population of cells in the sub-G1 phase, which is indicative of apoptotic cell death (Fig. 2A).

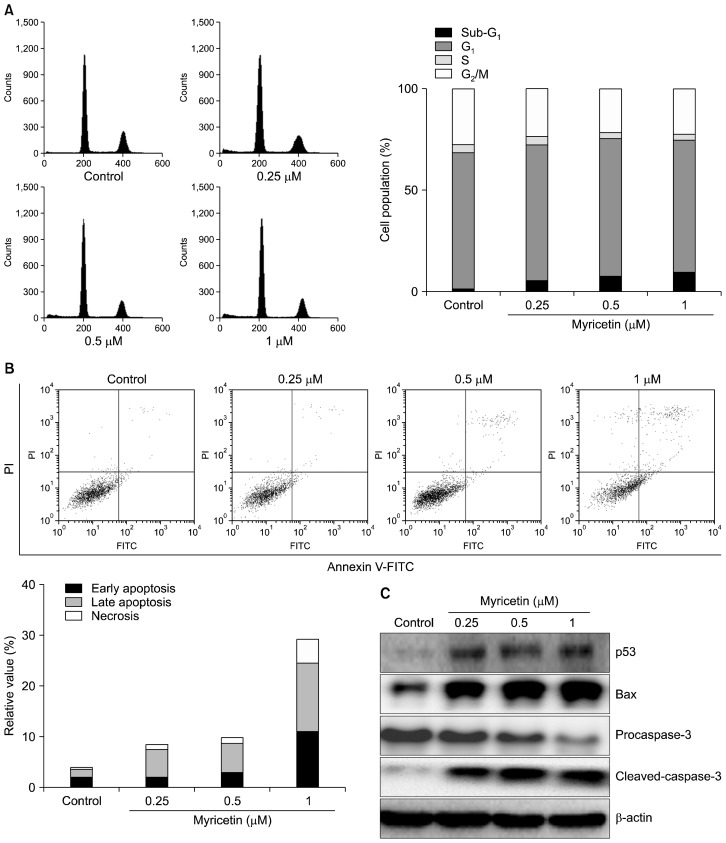

Figure 2.

Effects of myricetin on cell cycle progression and apoptosis in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). HUVECs were treated with myricetin (0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) for 24 hours, stained with propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. (A) The percentage distribution of cell population in each phase of cell cycle is shown. (B) Annexin V−/PI− (lower left), annexin V+/PI−(lower right), annexin V+/PI+ (upper right), and annexin V−/PI+ (upper left) cells represent surviving, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic apoptotic cells; values are representative of three separate experiments. (C) The levels of apoptosis-related proteins were analyzed by Western blotting; β-actin was used as an internal control. V-FITC, V-fluorescein isothiocyanate.

2. Effects of myricetin on apoptosis induction

The apoptotic effect of myricetin was further confirmed by flow cytometric analysis based on annexin V-FITC/PI double staining. The results (Fig. 2B) showed that exposure to myricetin (0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) for 24 hours increased the number of late apoptotic and necrotic cells in a dose-dependent manner. Particularly, myricetin (1 μM) increased the percentage of apoptotic cells (24.47%) compared to vehicle treatment (3.55%). We further evaluated the effects of myricetin on the regulators of apoptosis. Western blot analysis revealed that exposure to myricetin for 24 hours increased the levels of p53 and Bax (pro-apoptotic protein) and induced the cleavage of procaspase-3 to caspase-3 (Fig. 2C).

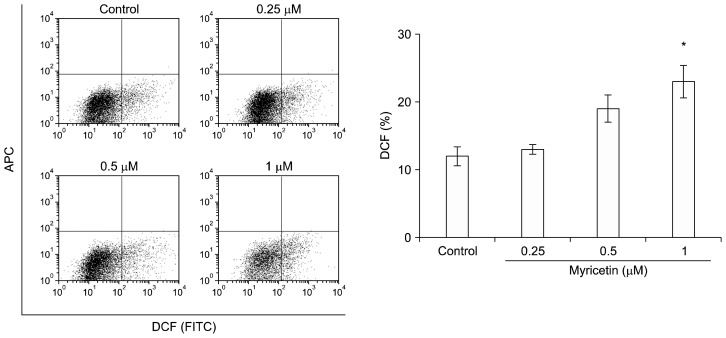

3. Effects of myricetin on intracellular oxidative stress

To investigate whether myricetin induced apoptosis through the generation of intracellular ROS, its effects on ROS levels were analyzed using an oxidant-sensitive fluorescent dye in the endothelial cells; myricetin (1 μM) significantly increased intracellular ROS levels compared to vehicle treatment (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of myricetin on the mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). ROS levels were quantified using an oxidant-sensitive dye, H2DCFDA, in HUVECs exposed to myricetin (0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) for 24 hours; values represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments; *P < 0.05 compared with control. APC, allophycocyamine; DCF, dichlorofluorescein; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

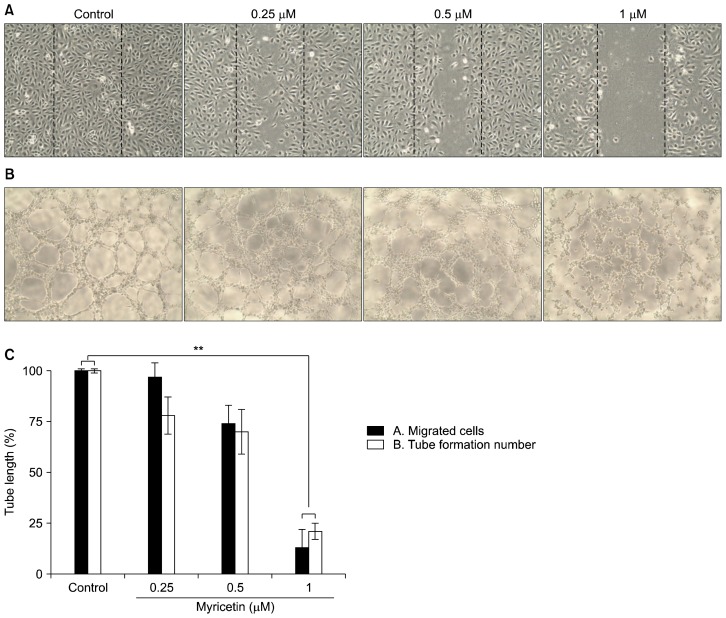

4. Effects of myricetin on migration and tube formation in endothelial cells

Endothelial cell migration and tube formation are essential steps in angiogenesis. Therefore, we determined the effects of myricetin on endothelial cell migration using a wound healing assay. Myricetin suppressed the migration of HUVECs in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4A and 4C). We also observed capillary-like tube structures after incubation for 4 to 8 hours in Matrigel (Fig. 4B and 4C). However, myricetin treatment resulted in broken and foreshortened tubes, indicating that it markedly inhibits vascular formation in HUVECs.

Figure 4.

Effects of myricetin on migration and tube formation in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). (A) HUVECs were grown to confluence in 6-well plates, scratch-wounded, and treated with the indicated concentrations of myricetin. Cell migration was visualized under an optical microscope (×100). (B) HUVECs were cultured in 96-well plates coated with Matrigel and incubated for 4 to 8 hours in the absence or presence of myricetin (×100). (C) The numbers of migrated cells and tube formations in HUVECs after myricetin treatment were counted; values represent the mean ± SD; **P < 0.01 compared with control.

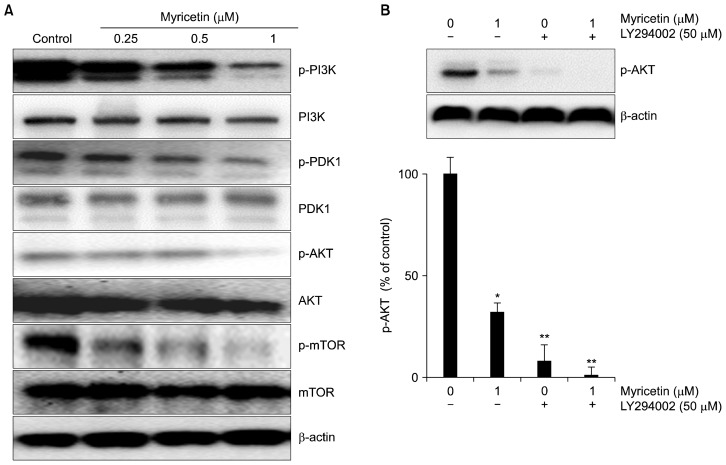

5. Effects of myricetin on PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling

To investigate whether myricetin affected the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, the constitutive activation of downstream targets of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway was evaluated in HUVECs. Myricetin attenuated the phosphorylation of both PI3K and PDK1 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). In addition, it inhibited Akt phosphorylation, indicating that it suppresses mTOR signaling in HUVECs. We also found that co-treatment with an Akt inhibitor, LY294002, and myricetin synergistically suppressed Akt activation (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of myricetin on the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). (A) HUVECs were treated with myricetin (0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) for 24 hours. Protein samples (40 μg) were subjected to 6% to 15% SDS-PAGE and the levels of PI3K, PDK1, Akt, mTOR, and their phosphorylated forms were detected by Western blotting. (B) The cells were treated with myricetin in combination with an Akt inhibitor, LY294002, and the level of p-Akt was detected by Western blotting; β-actin was used as the internal control. Values represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with control.

DISCUSSION

Angiogenesis inhibitors hold significant anticancer potential. Due to fewer adverse effects, herbal or natural drugs are preferred over synthetic drugs.27,28 The inhibition of angiogenesis slows tumor growth,29 making antiangiogenic therapy a promising anticancer treatment option.30 Flavonoids have been reported to exert antitumor effects.31,32 Myricetin, a flavonoid that is abundant in fruits and vegetables, exhibits anticancer and anti-diabetic properties.33 It has been shown to inhibit proliferation, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis in human colon cancer cells.34 It suppresses UVB-induced skin cancer,35 inhibits the growth of MCF7 cells,36 and acts as an agonist of estrogen receptor alpha in breast cancer.37 Myricetin has been shown to induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells without damaging normal pancreatic ductal cells; it is reported to activate mitochondrial apoptosis by increasing the levels of annexin V- and TUNEL-positive cells, the release of cytochrome c, and the expression of caspase-9 and caspase-3.38 In general, angiogenic and vasculogenic inhibitors suppress endothelial cell proliferation. However, the effects of myricetin on endothelial cells remains unexplored. In the present study, we demonstrated that myricetin exerts an antiangiogenic activity by inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis and inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in HUVECs.

Apoptosis is a highly regulated process; the tumor suppressor protein, p53, induces as well as inhibits apoptosis.39 It regulates DNA repair and cell cycle progression.40 The induction of apoptosis by myricetin was confirmed by an increase in the percentage of annexin V-positive cells, the levels of p53 and Bax, and the cleavage of procaspase-3 to caspase-3. Oxidative stress occurs due to an imbalance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant cellular factors, and causes cell damage.41 ROS comprise superoxide and hydroxyl radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and singlet oxygen; they are byproducts of mitochondrial respiration and contribute to oxidative stress. Increased intracellular levels of ROS lead to the activation of apoptotic pathways.42 Upon analysis using an oxidant-sensitive fluorescent dye (H2DCFDA), we found that myricetin significantly enhanced the production of intracellular ROS in HUVECs, indicating that it induces apoptosis by increasing intracellular ROS levels. Mitochondria play a crucial role in respiratory metabolism and cell cycle progression; they regulate extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways, and affect cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. They are the major cell organelles responsible for intracellular ROS production. Increased ROS levels reduce the mitochondrial membrane potential, thereby activating apoptotic pathways; therefore, mitochondrial dysfunction leads to apoptosis.43 The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and its downstream targets are activated during angiogenesis.44 Akt is a serine/threonine kinase that regulates a variety of cellular functions, including cell growth, proliferation, migration, protein synthesis, transcription, survival, and angiogenesis.45 mTOR kinase, the central regulator of cell metabolism, growth, proliferation, and survival, is also activated during tumor initiation, progression, and angiogenesis.9,45

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that myricetin inhibits angiogenesis in endothelial cells by inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis and inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling. Therefore, we propose that myricetin, as an antiangiogenic agent, is a promising anticancer drug candidate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2014R1A1A3052322).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Olson JD, Mintz A, et al. Type-2 pericytes participate in normal and tumoral angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2014;307:C25–38. 10.1152/ajpcell.00084.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature 2005;438:967–74. 10.1038/nature04483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang H, Chen AY, Rojanasakul Y, Ye X, Rankin GO, Chen YC. Dietary compounds galangin and myricetin suppress ovarian cancer cell angiogenesis. J Funct Foods 2015;15:464–75. 10.1016/j.jff.2015.03.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauer H, Günther J, Hescheler J, Wartenberg M. Thalidomide inhibits angiogenesis in embryoid bodies by the generation of hydroxyl radicals. Am J Pathol 2000;156:151–8. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64714-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Wetering S, van Buul JD, Quik S, Mul FP, Anthony EC, ten Klooster JP, et al. Reactive oxygen species mediate Rac-induced loss of cell-cell adhesion in primary human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci 2002;115:1837–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 2003;552:335–44. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yap TA, Garrett MD, Walton MI, Raynaud F, de Bono JS, Workman P. Targeting the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway: progress, pitfalls, and promises. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2008;8:393–412. 10.1016/j.coph.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bader AG, Kang S, Zhao L, Vogt PK. Oncogenic PI3K deregulates transcription and translation. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:921–9. 10.1038/nrc1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karar J, Maity A. PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in angiogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci 2011;4:51. 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim GD, Oh J, Park HJ, Bae K, Lee SK. Magnolol inhibits angiogenesis by regulating ROS-mediated apoptosis and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in mES/EB-derived endothelial-like cells. Int J Oncol 2013;43:600–10. 10.3892/ijo.2013.1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nabavi SF, Russo GL, Daglia M, Nabavi SM. Role of quercetin as an alternative for obesity treatment: you are what you eat! Food Chem 2015;179:305–10. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nabavi SM, Marchese A, Izadi M, Curti V, Daglia M, Nabavi SF. Plants belonging to the genus Thymus as antibacterial agents: from farm to pharmacy. Food Chem 2015;173:339–47. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gates MA, Vitonis AF, Tworoger SS, Rosner B, Titus-Ernstoff L, Hankinson SE, et al. Flavonoid intake and ovarian cancer risk in a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer 2009;124: 1918–25. 10.1002/ijc.24151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang L, Paonessa JD, Zhang Y, Ambrosone CB, McCann SE. Total isothiocyanate yield from raw cruciferous vegetables commonly consumed in the United States. J Funct Foods 2013;5:1996–2001. 10.1016/j.jff.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrington R, Williamson G, Bennett RN, Davis BD, Brodbelt JS, Kroon PA. Absorption, conjugation and efflux of the flavonoids, kaempferol and galangin, Using the Intestinal CACO-2/TC7 Cell Model. J Funct Foods 2009;1:74–87. 10.1016/j.jff.2008.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arif H, Rehmani N, Farhan M, Ahmad A, Hadi SM. Mobilization of copper ions by flavonoids in human peripheral lymphocytes leads to oxidative DNA breakage: a structure activity study. Int J Mol Sci 2015;16:26754–69. 10.3390/ijms161125992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gacche RN, Shegokar HD, Gond DS, Yang Z, Jadhav AD. Evaluation of selected flavonoids as antiangiogenic, anticancer, and radical scavenging agents: an experimental and in silico analysis. Cell Biochem Biophys 2011;61:651–63. 10.1007/s12013-011-9251-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noolu B, Gogulothu R, Bhat M, Qadri SS, Reddy VS, Reddy GB, et al. In vivo inhibition of proteasome activity and tumour growth by murraya koenigii leaf extract in breast cancer xenografts and by its active flavonoids in breast cancer cells. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2016;16:1605–14. 10.2174/1871520616666160520112210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Häkkinen SH, Kärenlampi SO, Heinonen IM, Mykkänen HM, Törrönen AR. Content of the flavonols quercetin, myricetin, and kaempferol in 25 edible berries. J Agric Food Chem 1999;47: 2274–9. 10.1021/jf9811065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribeiro de Lima MT, Waffo-Téguo P, Teissedre PL, Pujolas A, Vercauteren J, Cabanis JC, et al. Determination of stilbenes (trans-astringin, cis- and trans-piceid, and cis- and trans-resveratrol) in Portuguese wines. J Agric Food Chem 1999;47:2666–70. 10.1021/jf9900884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sellappan S, Akoh CC. Flavonoids and antioxidant capacity of Georgia-grown Vidalia onions. J Agric Food Chem 2002;50:5338–42. 10.1021/jf020333a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang XH, Chen SY, Tang L, Shen YZ, Luo L, Xu CW, et al. Myricetin induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells through Akt/p70S6K/bad signaling and mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2013;13:1575–81. 10.2174/1871520613666131125123059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J, Papp LV, Fang J, Rodriguez-Nieto S, Zhivotovsky B, Holmgren A. Inhibition of Mammalian thioredoxin reductase by some flavonoids: implications for myricetin and quercetin anticancer activity. Cancer Res 2006;66:4410–8. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KW, Kang NJ, Rogozin EA, Kim HG, Cho YY, Bode AM, et al. Myricetin is a novel natural inhibitor of neoplastic cell transformation and MEK1. Carcinogenesis 2007;28:1918–27. 10.1093/carcin/bgm110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JD, Liu L, Guo W, Meydani M. Chemical structure of flavonols in relation to modulation of angiogenesis and immune-endothelial cell adhesion. J Nutr Biochem 2006;17:165–76. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim GD, Kim GJ, Seok JH, Chung HM, Chee KM, Rhee GS. Differentiation of endothelial cells derived from mouse embryoid bodies: a possible in vitro vasculogenesis model. Toxicol Lett 2008;180:166–73. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim KM, Heo DR, Lee J, Park JS, Baek MG, Yi JM, et al. 5,3′-Dihydroxy-6,7,4′-trimethoxyflavanone exerts its anticancer and antiangiogenesis effects through regulation of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in human lung cancer cells. Chem Biol Interact 2015;225:32–9. 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Marine natural products and related compounds in clinical and advanced preclinical trials. J Nat Prod 2004;67:1216–38. 10.1021/np040031y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tong YG, Zhang XW, Geng MY, Yue JM, Xin XL, Tian F, et al. Pseudolarix acid B, a new tubulin-binding agent, inhibits angiogenesis by interacting with a novel binding site on tubulin. Mol Pharmacol 2006;69:1226–33. 10.1124/mol.105.020537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen SH, Murphy DA, Lassoued W, Thurston G, Feldman MD, Lee WM. Activated STAT3 is a mediator and biomarker of VEGF endothelial activation. Cancer Biol Ther 2008;7:1994–2003. 10.4161/cbt.7.12.6967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren W, Qiao Z, Wang H, Zhu L, Zhang L. Flavonoids: promising anticancer agents. Med Res Rev 2003;23:519–34. 10.1002/med.10033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galati G, O’Brien PJ. Potential toxicity of flavonoids and other dietary phenolics: significance for their chemopreventive and anti-cancer properties. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;37:287–303. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López-Lázaro M, Willmore E, Austin CA. The dietary flavonoids myricetin and fisetin act as dual inhibitors of DNA top-oisomerases I and II in cells. Mutat Res 2010;696:41–7. 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuntz S, Wenzel U, Daniel H. Comparative analysis of the effects of flavonoids on proliferation, cytotoxicity, and apoptosis in human colon cancer cell lines. Eur J Nutr 1999;38:133–42. 10.1007/s003940050054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung SK, Lee KW, Byun S, Kang NJ, Lim SH, Heo YS, et al. Myricetin suppresses UVB-induced skin cancer by targeting Fyn. Cancer Res 2008;68:6021–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodgers EH, Grant MH. The effect of the flavonoids, quercetin, myricetin and epicatechin on the growth and enzyme activities of MCF7 human breast cancer cells. Chem Biol Interact 1998;116:213–28. 10.1016/S0009-2797(98)00092-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maggiolini M, Recchia AG, Bonofiglio D, Catalano S, Vivacqua A, Carpino A, et al. The red wine phenolics piceatannol and myricetin act as agonists for estrogen receptor alpha in human breast cancer cells. J Mol Endocrinol 2005;35:269–81. 10.1677/jme.1.01783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim W, Yang HJ, Youn H, Yun YJ, Seong KM, Youn B. Myricetin inhibits Akt survival signaling and induces Bad-mediated apoptosis in a low dose ultraviolet (UV)-B-irradiated HaCaT human immortalized keratinocytes. J Radiat Res 2010;51:285–96. 10.1269/jrr.09141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe SW, Schmitt EM, Smith SW, Osborne BA, Jacks T. p53 is required for radiation-induced apoptosis in mouse thymocytes. Nature 1993;362:847–9. 10.1038/362847a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haunstetter A, Izumo S. Apoptosis: basic mechanisms and implications for cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 1998;82:1111–29. 10.1161/01.RES.82.11.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang L, Wang P, Wang H, Li Q, Teng H, Liu Z, et al. Fucoidan derived from Undaria pinnatifida induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma SMMC-7721 cells via the ROS-mediated mitochondrial pathway. Mar Drugs 2013;11:1961–76. 10.3390/md11061961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu HL, Tang W, Du GH, Kokudo N. Targeting apoptosis pathways in cancer with magnolol and honokiol, bioactive constituents of the bark of Magnolia officinalis. Drug Discov Ther 2011;5:202–10. 10.5582/ddt.2011.v5.5.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon HU, Haj-Yehia A, Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 2000;5:415–8. 10.1023/A:1009616228304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato F, Kurokawa M, Yamauchi N, Hattori MA. Gene silencing of myostatin in differentiation of chicken embryonic myoblasts by small interfering RNA. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006;291: C538–45. 10.1152/ajpcell.00543.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell 2007;129:1261–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]