Abstract

Introduction

Identifying at what point atrophy rates first change in Alzheimer’s disease is important for informing design of presymptomatic trials.

Methods

Serial T1-weighed magnetic resonance imaging scans of 94 participants (28 noncarriers, 66 carriers) from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network were used to measure brain, ventricular, and hippocampal atrophy rates. For each structure, nonlinear mixed-effects models estimated the change-points when atrophy rates deviate from normal and the rates of change before and after this point.

Results

Atrophy increased after the change-point, which occurred 1–1.5 years (assuming a single step change in atrophy rate) or 3–8 years (assuming gradual acceleration of atrophy) before expected symptom onset. At expected symptom onset, estimated atrophy rates were at least 3.6 times than those before the change-point.

Discussion

Atrophy rates are pathologically increased up to seven years before “expected onset”. During this period, atrophy rates may be useful for inclusion and tracking of disease progression.

Keywords: Longitudinal, Atrophy, Alzheimer’s disease, Dementia, Autosomal dominant, Neuroimaging, MRI, Boundary Shift Integral, Nonlinear modeling, Change-point

1. Introduction

Testing potentially disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) during the preclinical phase [1] presents challenges of recruitment and staging of asymptomatic individuals, as well as determining suitable measures for assessing disease modification. One recruitment strategy is to study members of families known to carry a pathogenic mutation in a gene—presenilin 1 (PSEN1), presenilin 2 (PSEN2), or amyloid precursor protein (APP)—that causes autosomal dominant AD (ADAD). These mutations have almost 100% penetrance, and ~50% of at-risk individuals are carriers. ADAD typically has an early and relatively predictable age at symptom onset [2,3]. The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) is a multicentre observational study of individuals at risk of, or affected by, ADAD. DIAN performs longitudinal assessments of imaging, fluid biomarkers, and cognitive function, which reflect pathological features in ADAD [4] and sporadic AD [5]. In particular, cerebral atrophy measures derived from volumetric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used as biomarkers of neurodegeneration and as outcome measures in trials [6].

Longitudinal data from presymptomatic ADAD individuals provide a unique opportunity to determine when atrophy rates begin to diverge from normal. Previous cross-sectional or small longitudinal studies report a wide range of estimates of this point of divergence: from 10 years before [4,7] to 7 years after [8] expected clinical onset (as determined by the affected parent’s age at onset).

We used serial MRI data from DIAN to model cerebral atrophy rates during presymptomatic and early symptomatic stages of ADAD. We assessed whole brain and hippocampal atrophy and ventricular expansion, three well-established imaging measures used as exploratory endpoints in clinical trials [6]. We hypothesize that presymptomatic carriers have similar atrophy rates to noncarriers (NC) up until a “change-point” when the biomarker starts to diverge from normal. This hypothesis is consistent with models of sporadic AD [5] that assume a sigmoidal trajectory and cross-sectional findings from the DIAN cohort [4,7]. We used two nonlinear mixed-effects models (Supplementary Material A) to estimate the timing of change-points relative to expected symptom onset and atrophy rates before and after these change-points. The first model assumes that the atrophy rate undergoes a single “step change” to a new, stable value; whereas the second model assumes a “gradual acceleration” in atrophy rate after the change-point. These models help characterize when therapeutic effects on brain atrophy could potentially be observed in presymptomatic ADAD and could help focus future sample size calculations for upcoming prevention trials.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

All participants were members of DIAN [9], and details of participating sites are available online (http://dian-info.org). The study received prior approval from appropriate Institutional Review Boards and Ethics Committees at each site. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Genotyping was performed to determine the presence of an ADAD mutation for each at-risk participant. A semistructured interview assessed the expected age at onset (EAO), based on when the affected parent first showed progressive cognitive decline. Estimated years from expected symptom onset (EYO) is the difference between age at scan and EAO [3]. Negative values indicate years before expected onset and positive values years after.

At the sixth data freeze (July 2013), there were 102 participants with two or more MRI scans available and complete data (mutation status, age, EAO, and global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score [10]).

2.2. Volumetric MRI

Volumetric T1-weighted scans were acquired on 3-Tesla MRI scanners using Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative standardized protocols [11] and corrected for intensity inhomogeneity [12]. Whole brain and hippocampal regions were automatically segmented [13–15]. Lateral ventricles were delineated semiautomatically by an expert rater. Baseline volumetric measures were corrected for total intracranial volume (TIV), calculated using an automated technique [16]. For each structure, volume change was directly measured using a group-wise implementation [17–19] of the Boundary Shift Integral [20] to ensure longitudinal consistency. A trained image analyst, blinded to participants’ mutation and clinical status, reviewed all raw and processed images.

2.3. Clinical classification

Participants were classified into four groups, based on mutation status, global CDR score, and actual age at onset (where this had occurred), determined by Uniform Data Set form B9, “Clinical judgment of symptoms” [21]:

Mutation NC; our control group.

Presymptomatic mutation carriers (pMut+); included mutation carriers with a global CDR score of 0 at both their first two visits.

Questionably or mildly symptomatic mutation carriers (qMut+); included participants with at least one global CDR score of 0.5 during their first two visits, with the other visit being either 0 or 0.5. We excluded from this group the participants who had a reported onset more than four years before study entry.

Overtly symptomatic mutation carriers (sMut+); included participants with a CDR score of 1.0 or greater at either (or both) of their first two visits or who were more than four years after reported onset at study entry.

Eight participants were excluded from the analysis: seven (one NC, four pMut+, one qMut+, and one sMut+) were identified during initial visual review of the image data and excluded due to non-Alzheimer’s pathology (e.g., infarct, neoplasm), imaging artifacts, or acquisition-related changes likely to result in unreliable atrophy measures. An additional participant (qMut+) was excluded due to moderate motion artifacts on follow-up imaging and implausible growth in brain and hippocampi. As part of the sensitivity analysis, we reran the model including this participant (Supplementary Material B).

Two participants who initially satisfied the qMut+ criteria were retrospectively reclassified as sMut+, as both participants had consistent evidence of cognitive decline over a sustained period.

Our final sample therefore included 94 participants: 24 pMut+, 18 qMut+, 24 sMut+, and 28 NC. Of the 66 carriers, 54 had mutations in PSEN1, three in PSEN2, and nine in APP. There were 66 participants with two MR scans, 20 with three, and eight with four scans. The scan interval between baseline and follow-up ranged from 0.9 to 3.3 years and was independent of carrier status or clinical severity. Two participants (one qMut+ and one sMut+) had inadequate image quality for analyses involving hippocampi.

2.4. Statistical analysis

To compare baseline values between each of the three mutations groups (pMut+, qMut+, and sMut+) and the noncarrier group, ANOVA models were used for age, EYO, and TIV, whereas logistic regression was used for apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 positivity and sex. A generalized least squares linear regression model that allows different group-specific residual variances was used to compare baseline volumes (standardized to mean TIV) between each of the three carrier groups and noncarriers.

The change-point model [22–24] was used to explore brain, ventricular, and hippocampal atrophy rates (Supplementary Material A provides a detailed model description). As the focus of our study was the presymptomatic and earliest symptomatic stages of ADAD, the model included NC, presymptomatic, and questionably symptomatic carriers (pMut+/qMut+).

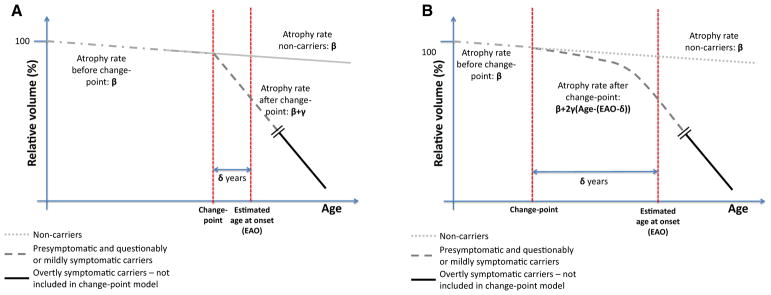

Fig. 1 provides a schematic representation of the “step change” and “gradual acceleration” change-point models. In both, β represents the shared atrophy rate for NC and pMut+/qMut+groups before the change-point, which takes place δ years before or after the EAO. Due to limited data, δ (for a specific brain structure) was assumed to be the same for all pMut+/qMut+ individuals.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the “step change” (A) and “gradual acceleration” (B) change-point models.

For the “step change” model, γ is the change in atrophy rate for the pMut+/qMut+ group after the change-point. In the “gradual acceleration” model, the atrophy rate for the pMut+/qMut+ group accelerates after the change-point by a value of 2γ per year. With each model, we estimated β, γ, and δ for each region, and using these, we estimated atrophy rates at various points before and after EAO.

Our change-point model was not designed to estimate atrophy rates several years after symptom onset; to do so, we risked distorting a model that was designed to focus on the progression from early changes to clinical symptoms. Thus, a separate linear mixed-effects random-slopes model (with no change-point) was used to model atrophy rates of the sMut+ group, assuming all observations were after the change-point.

The change-point models are nonlinear extensions of a previously described linear mixed-effects random-slopes model [25] (Supplementary Material A). Atrophy measures were log-transformed to provide symmetric approximations of percentage change from baseline. The change-point models were implemented using SAS (version 9.4) procedure NLMIXED, which simultaneously estimated β, γ, and δ. Robust estimates of uncertainty for these coefficients were obtained through bootstrapping [26,27], with 10,000 replicates and using bias corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals. Sensitivity of the estimates and confidence intervals to outliers was explored (see Supplementary Material B).

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical data. The sMut+ group was, as expected, older than the noncarriers, with smaller brain and hippocampal volumes and larger ventricular volumes (all TIV-adjusted), reflecting pathologic losses and larger TIV, which likely reflects the higher (albeit statistically nonsignificant) proportion of males in this group. The qMut+ group had smaller hippocampal volumes and larger ventricular volumes compared with noncarriers, whereas the preMut+ group just had smaller right hippocampal volumes.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and region volumes for participants included in the longitudinal analysis

| Demographics | Noncarriers (NC) | Presymptomatic mutation carriers (preMut+) | Questionably or mildly symptomatic mutation carriers (qMut+) | Overtly symptomatic mutation carriers (sMut+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 28 | 24 | 18 | 24 |

| Age, years (SD) | 41.0 (8.4) | 37.7 (10.1) | 39.1 (10.2) | 48.6 (8.2)§ |

| Sex, F/M | 17/11 | 16/8 | 11/7 | 10/14 |

| APOE status, No. (%)* | 6/28 (21%) | 7/24 (29%) | 6/18 (33%) | 7/24 (29%) |

| Estimated years from expected symptom onset (EYO), years (SD)† | −5.52 (8.62) | −8.05 (8.38) | −4.19 (5.76) | 4.01 (6.46)§ |

| TIV, mL (SD) | 1374 (129) | 1373 (142) | 1416 (124) | 1483 (164)§ |

| Brain volume, mL (95% CI)‡ | 1178 (1163, 1194) | 1182 (1162, 1201) | 1163 (1142, 1184) | 1055 (1028, 1081)§ |

| Ventricular volume, mL (95% CI)‡ | 15.2 (13.0, 17.46) | 15.4 (12.5, 18.3) | 20.0 (15.9, 24.0)§ | 34.3 (28.5, 40.1)§ |

| Left hippocampal volume, mL (95% CI)‡ | 3.01 (2.91, 3.10) | 2.90 (2.79, 3.00) | 2.73 (2.62, 2.84)§ | 2.45 (2.28, 2.61)§ |

| Right hippocampal volume, mL (95% CI)‡ | 3.08 (2.99, 3.17) | 2.93 (2.82, 3.01)§ | 2.76 (2.63, 2.89)§ | 2.55 (2.37, 2.73)§ |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; TIV, total intracranial volume; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Number (%) with APOE genotype 24, 34, or 44.

A negative value of EYO indicates that a participant joined the study before their expected age of onset, based on parental age at onset; EYO values for noncarriers are only indicative; EYO values for overtly symptomatic mutation carriers do not reflect clinically determined actual age of onset.

Regional volumes were standardized to the mean TIV using a linear regression model.

P <.05 versus NC.

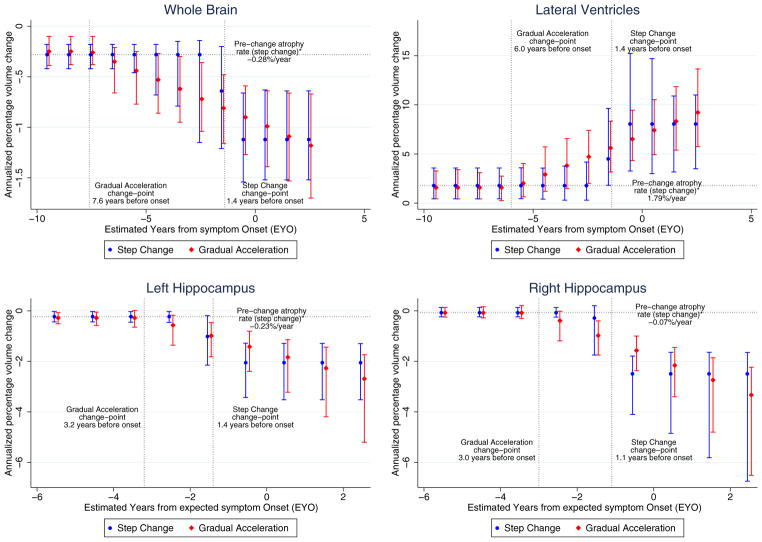

Tables 2 and 3 show the change-point model results for each structure. In the “step change” model, the pre-change atrophy rate (β) was statistically significant in every structure except the right hippocampus. In all regions, there were significant increases in atrophy rate (γ) after the change-point. This is demonstrated by deriving, from the results of the model, a ratio between the atrophy rate at EAO (1–0 years before) to the pre-change atrophy rate. This ratio was 4.0 for whole brain, 4.5 for ventricles, and 9.0 for left hippocampus, but it could not be produced for right hippocampus as the estimated prechange atrophy rate was small and not statistically significantly different from zero. However, the increase in γ after the change-point for the right hippocampus was larger than the corresponding coefficient in the results for the left hippocampus. The estimated change-point (δ) for brain, ventricle, and left hippocampus was 1.4 years before EAO and 1.1 years before EAO for the right hippocampus. For whole brain and left hippocampus, the confidence intervals for δ did not span zero, providing evidence that they occurred before EAO. Estimates of the ventricular change-point had greater uncertainty (−1.1 to 13.5 years) than the other structures. Tables 2 and 3 provide estimates for rates of change at various times before and after EAO.

Table 2.

Rates of change in whole brain and ventricular atrophy measures estimated using the step change and gradual acceleration change-point models

| Whole brain

|

Lateral ventricles

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step change | Gradual acceleration | Step change | Gradual acceleration | |

| Annualized rate of prechange atrophy (95% CI) | −0.28% (−0.42, −0.18) | −0.25% (−0.37, −0.11) | 1.79% (0.44, 3.58) | 1.59% (0.53, 2.91) |

| Postchange coefficient (95% CI)* | −0.84% (−1.22, −0.32) | −0.05 (−0.11, −0.01) | 6.29% (1.99, 9.18) | 0.45 (0.16, 1.17) |

| Change-point years before onset (95% CI) | 1.4 (0.5, 3.8) | 7.6 (2.3, 14.8) | 1.4 (−1.1, 13.5) | 6.0 (2.0, 15.5) |

| Atrophy rate (95% CI) | ||||

| 10–9 years before | −0.28% (−0.42, −0.18) | −0.25% (−0.39, −0.10) | 1.79% (0.44, 3.58) | 1.59% (0.44, 3.28) |

| 9–8 years before | −0.28% (−0.42, −0.18) | −0.25% (−0.38, −0.10) | 1.79% (0.44, 3.58) | 1.59% (0.43, 3.41) |

| 8–7 years before | −0.28% (−0.42, −0.18) | −0.26% (−0.38, −0.10) | 1.79% (0.44, 3.58) | 1.59% (0.43, 3.11) |

| 7–6 years before | −0.28% (−0.42, −0.18) | −0.35% (−0.66, −0.21) | 1.79% (0.44, 3.58) | 1.59% (0.26, 2.75) |

| 6–5 years before | −0.28% (−0.46, −0.18) | −0.44% (−0.77, −0.25) | 1.79% (0.46, 3.60) | 2.02% (0.64, 4.03) |

| 5–4 years before | −0.28% (−0.68, −0.18) | −0.53% (−0.86, −0.27) | 1.79% (0.41, 3.57) | 2.92% (1.20, 5.73) |

| 4–3 years before | −0.28% (−0.79, −0.15) | −0.62% (−0.95, −0.30) | 1.79% (0.30, 3.77) | 3.82% (1.49, 6.57) |

| 3–2 years before | −0.28% (−1.15, −0.14) | −0.72% (−1.04, −0.36) | 1.79% (0.30, 4.18) | 4.72% (2.00, 7.41) |

| 2–1 years before | −0.64% (−1.21, −0.20) | −0.81% (−1.16, −0.48) | 4.51% (1.82, 9.64) | 5.62% (3.17, 8.34) |

| 1–0 years before | −1.12% (−1.54, −0.66) | −0.90% (−1.27, −0.59) | 8.07% (3.27, 15.24) | 6.52% (4.34, 9.46) |

| 0–1 years after | −1.12% (−1.52, −0.63) | −0.99% (−1.39, −0.64) | 8.07% (3.00, 14.70) | 7.42% (4.93, 10.53) |

| 1–2 years after | −1.12% (−1.52, −0.64) | −1.09% (−1.53, −0.66) | 8.07% (3.18, 10.90) | 8.33% (5.39, 11.85) |

| 2–3 years after | −1.12% (−1.52, −0.64) | −1.18% (−1.70, −0.67) | 8.07% (3.50, 11.01) | 9.23% (5.76, 13.66) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence.

For the “step change” model, the postchange coefficient parameter of the model, γ, represents the change to the atrophy rate for presymptomatic and early symptomatic carriers after the change-point and has units of percentage per year. In the “gradual acceleration” model, the postchange coefficient is proportional to the rate of acceleration in the atrophy rate after the change-point. Due to this coefficient representing a time-squared term in the model, the rate of acceleration after the change-point is a value of 2γ per year. This coefficient has units of percentage per year squared.

Table 3.

Rates of change in left and right hippocampal atrophy measures estimated using the step change and gradual acceleration change-point models

| Left hippocampus

|

Right hippocampus

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step change | Gradual acceleration | Step change | Gradual acceleration | |

| Annualized rate of prechange atrophy (95% CI) | −0.23% (−0.44, −0.03) | −0.28% (−0.49, −0.07) | −0.07% (−0.24, 0.13) | −0.08% (−0.24, 0.13) |

| Postchange coefficient (95% CI)* | −1.82% (−3.28, −1.06) | −0.21 (−0.51, −0.12) | −2.42% (−6.45, −1.56) | −0.29 (−0.86, −0.15) |

| Change-point years before onset (95% CI) | 1.4 (0.9, 1.8) | 3.2 (2.0, 5.8) | 1.1 (−2.0, 1.8) | 3.0 (1.5, 6.2) |

| Atrophy rate | ||||

| 6–5 years before | −0.23% (−0.44, −0.03) | −0.28% (−0.51, −0.07) | −0.07% (−0.24, 0.13) | −0.08% (−0.25, 0.14) |

| 5–4 years before | −0.23% (−0.44, −0.03) | −0.28% (−0.58, −0.05) | −0.07% (−0.24, 0.13) | −0.08% (−0.28, 0.16) |

| 4–3 years before | −0.23% (−0.45, −0.03) | −0.28% (−0.65, 0.01) | −0.07% (−0.24, 0.13) | −0.08% (−0.30, 0.21) |

| 3–2 years before | −0.23% (−0.46, −0.03) | −0.57% (−1.36, −0.18) | −0.07% (−0.25, 0.13) | −0.39% (−1.19, −0.02) |

| 2–1 years before | −1.02% (−2.15, −0.19) | −0.99% (−1.82, −0.47) | −0.29% (−1.75, 0.20) | −0.98% (−1.75, −0.40) |

| 1–0 years before | −2.06% (−3.43, −1.28) | −1.42% (−2.40, −0.81) | −2.49% (−4.10, −1.79) | −1.57% (−2.37, −1.00) |

| 0–1 years after | −2.06% (−3.52, −1.29) | −1.84% (−3.22, −1.14) | −2.49% (−4.85, −1.64) | −2.16% (−3.40, −1.45) |

| 1–2 years after | −2.06% (−3.52, −1.29) | −2.27% (−4.19, −1.44) | −2.49% (−5.81, −1.64) | −2.74% (−4.80, −1.86) |

| 2–3 years after | −2.06% (−3.52, −1.30) | −2.69% (−5.20, −1.74) | −2.49% (−6.74, −1.65) | −3.33% (−6.51, −2.23) |

For the “step change” model, the postchange coefficient parameter of the model, γ, represents the change to the atrophy rate for presymptomatic and early symptomatic carriers after the change-point and has units of percentage per year. In the “gradual acceleration” model, the postchange coefficient is proportional to the rate of acceleration in the atrophy rate after the change-point. Due to this coefficient representing a time-squared term in the model, the rate of acceleration after the change-point is a value of 2γ per year. This coefficient has units of percentage per year squared.

As with the “step change” model, in the “gradual acceleration” model, all structures except the right hippocampus had statistically significant prechange atrophy rates. All regions had coefficients (γ) indicating statistically significant increased neurodegeneration after the change-point. The ratio of atrophy rate at EAO to the prechange rate was 3.6 for whole brain, 4.1 for ventricles, and 5.1 for left hippocampus. The ratio for the right hippocampus was also not available due to the small, nonsignificant prechange atrophy rate, but the coefficient (γ) indicated that the right hippocampus had a similar increase toward neurodegeneration as the left. The change-point estimates (δ) for the whole brain and ventricles were 3.0–4.6 years earlier than for the hippocampi. For all structures, the confidence intervals for δ did not span zero. Fig. 2 shows estimated atrophy rates and 95% confidence intervals from both models in relation to EYO.

Fig. 2.

Rates of change estimated from the “step change” and “gradual acceleration” models, as a function of the estimated years from symptom onset (EYO) for the pMut+/qMut+ carriers. The figure shows the relationship between rate of annualized volume change (%) and EYO. 95% confidence intervals are included, computed from the bootstrap samples. Although the schematics in Fig. 1 display the decline in actual volume, these graphs represent the rate of change in volume. A horizontal line indicates the estimated atrophy rate (from the “step change” model) for noncarriers and carriers before the change-point before any deviation from normal rates of change. Vertical dotted lines indicate the change-points for both the “step change” and “gradual acceleration” models. For periods that include the change-point, the estimated rate of atrophy is a weighted combination, representing the transition from the pre-change-point atrophy to the post-change-point atrophy. Top left: whole brain; top right: lateral ventricles; bottom left: left hippocampus; bottom right: right hippocampus.

In the sensitivity analysis, we reran the model including the participant with movement artifact and clinically implausible data (Supplementary Material B). The pattern of the results was not materially altered although the statistical significance of some parameter estimates was lost.

The estimated rates of change in sMut+ participants were approximately double for those found in pMut+/qMut+ carriers at EAO using the change-point models. The symptomatic rates were as follows: −2.41% (95% CI: −2.88 to −1.95) per year for whole brain, 15.0% (95% CI: 12.6–17.5) for ventricles, −4.70% (95% CI: −6.39 to −3.01) for left hippocampus, and −4.64% (95% CI: −5.68 to −3.60) for right hippocampus.

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to estimate when brain, ventricular, and hippocampal volume changes in ADAD diverge from noncarriers and to model the rates before and after this transition using serial MRI data from the DIAN cohort. We designed two nonlinear mixed-effects models: one assuming a single “step change” and another assuming a “gradual acceleration” in rates of atrophy after the change-point. This type of model has previously been used to investigate the trajectories of cognitive decline [23,28] and atrophy rates [29,30]. In all cases, there was evidence of increased atrophy after the change-point, suggesting that our models better reflect the nonlinear nature of atrophy in early-stage disease than a linear relationship would. The “gradual acceleration” model found evidence for all assessed regions that atrophy rates diverge from normal values before symptom onset, with the change-point occurring 3.0 to 7.6 years before EAO. The “step change” model found a change-point of 1.4 years before EAO for whole brain and left hippocampus but was unable to show evidence of a change-point preceding EAO for ventricles or right hippocampus.

4.1. Interpreting the change-point model results

A key advantage of using two different change-point models is that they provide complementary information about the timing of the change-point. The “step change” model provides the most conservative estimate of when atrophy rates diverge. In contrast, the “gradual acceleration” model is probably more biologically plausible, based on previous results in ADAD [4,7,31,32] and by the well-characterized spatial spread of neurodegeneration [33] that typically begins in the medial temporal lobe and gradually spreads into neocortical regions. However, there are caveats to the gradual acceleration model used. The nonlinear nature of the atrophy may vary between individuals, and a quadratic may not be the most appropriate fit. However, given the size of the data set, this approach minimizes risk of overfittings. Change-point models also avoid some of the pitfalls that can occur when including polynomial terms in a linear regression to model this nonlinear relationship [34]. Although a quadratic term could better capture the increase in atrophy rate observed around expected onset, it may also produce artifacts of increased atrophy in carriers who are decades before their expected onset.

Unlike linear models, change-point models can capture the different phases of atrophy/expansion during the long period of presymptomatic disease progression. Both models provide similar estimates of β (see Tables 2 and 3) and the prechange atrophy rate. This suggested age-related changes broadly consistent with previous aging studies [35–37], showing small but significant rates of whole-brain atrophy of the order of 0.2–0.6% per year and hippocampal atrophy of the order of 0.3–0.4% per year for similar age ranges to this cohort. From both models, there was evidence of increased atrophy after the change-point in all regions.

4.2. Estimating onset of pathological atrophy

It is unclear when disease-related atrophy first becomes evident in ADAD. Cross-sectional results from PSEN1 E280 A mutation carriers [38,39] and DIAN [4,7] suggest atrophy of hippocampi diverge from noncarriers ~6 years and 10 years before symptom onset, respectively, earlier than in our models. However, initial longitudinal results from DIAN [7] (N = 53) identified increased atrophy rates only in symptomatic carriers. A study of 13 presymptomatic PSEN1 carriers found increased cortical thickness at baseline but subsequent thinning of a number of cortical regions [40], suggesting a nonlinear nature to presymptomatic changes–with gray matter increases preceding declines.

Most previous longitudinal volumetric MRI studies of ADAD mutation carriers have been relatively small, single-site studies. One study following presymptomatic participants to clinical onset indicated pathological hippocampal atrophy rates appeared ~5.5 years before AD diagnosis [31]. Weston et al. [41] examined cortical thickness longitudinally in presymptomatic carriers and detected significant losses in the precuneus eight years before EAO. These values are consistent with our findings using a gradual acceleration model where the change-point was 7.6 years before onset. However, another study of 16 ADAD mutation carriers (seven with long-term follow-up) did not detect structural MRI changes until after symptom onset [8], suggesting that a heterogeneity in these small cohorts and the methods used to analyze them may generate markedly different results.

No prior ADAD study has used change-point models, making it difficult to compare estimates. However, there are similarities between our findings and sporadic AD studies that used similar approaches. A study of 79 elderly patients, 37 of whom developed mild cognitive impairment (MCI), reported a ventricular expansion change-point 2.3 years before MCI diagnosis [29]. Another longitudinal study (N = 296, 66 progressing to MCI) found a similar hippocampal atrophy change-point of 2–4 years before clinical onset [30]. Their estimate of a 0.2% per year prechange hippocampal atrophy rate accords with ours (0.2% left, 0.1% right). Their postchange atrophy rate estimate for the right hippocampus (2.7% per year) was similar to our value (2.5%) whereas their left hippocampal rate estimate (1.2%) was lower than ours (2.1%).

4.3. Predicting clinical onset in ADAD

An important challenge is what estimate to use for clinical onset before it has occurred. Many studies, including ours, use an EAO based on when the affected parent first developed symptoms consistent with progressive decline. Other measures are based on the average across all previously affected family members, or the reported age at onset in the literature for a particular mutation [3]. However, each is an imperfect estimate of the future age at onset.

If future clinical trials use EYO as an inclusion criterion, then it is the distribution of atrophy rates relative to EAO that is of importance. However, if we wish to understand the etiology of the disease, then the distribution of atrophy rates relative to actual onset is more informative, as change-points are likely to be more strongly related to actual rather than EAO. The effect of switching from actual to expected onset in statistical models will change the form of the estimated volume change over time, smoothing it to some degree. Without knowledge of actual onset, this effect is not easily avoided. We did, however, attempt to reduce its impact by excluding overtly symptomatic carriers from our change-point models.

Identifying precisely when clinical onset has occurred is not straightforward. To facilitate standardization across sites, DIAN rigorously monitors how raters perform CDR and other assessments [42]. In at-risk individuals, other factors can influence cognitive function or behavioral changes including stress, anxiety, and the constant level of vigilance and introspection that participants experience. In this study, there were six qMut+participants who reverted from a baseline global CDR of 0.5 to 0 at follow-up. These cases highlight the subtle nature of transitions from unimpaired to “affected” and the potential confounds of mood disturbance and other factors. We addressed this uncertainty by including questionably or mildly symptomatic carriers in our change-point models.

4.4. Limitations and future work

Change-point models have been used to model atrophy rates in preclinical sporadic AD [29,30]. We expand on these approaches by adapting the model for repeated measures of direct change instead of individual volumetric measures and allowing for either a “step change” or “gradual acceleration” after the change-point. Due to the nonlinear nature of our models and the use of bootstrapping to obtain confidence intervals for the model coefficients, these models are susceptible to influential outliers, especially with smaller sample sizes (see the sensitivity analysis in Supplementary Material B). Additional longitudinal data should provide improved robustness against such issues.

No prior study has characterized the progression of atrophy in such a large cohort of presymptomatic and earliest symptomatic ADAD. There are active multicentre clinical trials underway that involve participants from DIAN [43], and the samples from our analysis should more closely reflect a clinical trial setting. Whole brain, lateral ventricles, and hippocampi are the most studied structures in sporadic AD and are often used as trial outcome measures. From the results, these atrophy measures appear to be elevated compared with noncarriers approximately 5 years before expected onset, making them best suited for prevention trials in ADAD from this period onward. Given the evidence of presymptomatic atrophy in specific cortical regions [40,41], future application of the change-point model could involve studying atrophy rates of specific cortical structures, such as the precuneus and posterior cingulate. Atrophy in these structures may appear earlier and thus be better suited for trials that target presymptomatic patients. In addition, the model should incorporate information from other biomarkers including cerebrospinal fluid amyloid and tau concentrations, to determine how markers of these pathologies affect the timing of the change-point. Finally, it is essential to understand which preclinical changes in ADAD generalize to sporadic AD, as differences in the structures preferentially affected appear to exist [44].

5. Conclusions

Atrophy rates increase in ADAD some years before expected symptom onset. Using two different change-point models, we can characterize when this change occurs. The “step change” model provides a minimum estimate, 1.4 years before expected onset. The “gradual acceleration” model provides a more biologically plausible approach toward how atrophy rates diverge from normal, with brain atrophy rates showing pathological acceleration ~7.6 years before expected onset and hippocampal rates changing ~3.0 years before expected onset. These models may help predict the time to clinical onset for presymptomatic individuals with increased atrophy and identify individuals for prevention trials.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: We searched PubMed for longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies of brain atrophy in autosomal dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease (ADAD) and preclinical sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (published Jan 1, 1996–May 31, 2016). We have appropriately cited the relevant references.

Interpretation: This study extends previous cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis in ADAD by examining the nonlinear trajectories of atrophy rates in key structures during the presymptomatic and earliest symptomatic stages of the disease, identifying when these rates are likely to diverge from normal. Our findings have implications for secondary prevention trials, where brain atrophy is a potential outcome measure.

Future directions: Future studies should explore the role of underlying mechanisms, using fluorodeoxy-glucose and tau positron emission tomography and other magnetic resonance imaging–based modalities techniques to investigate changes in molecular pathology, microstructure, and brain activity. It will be important to understand whether changes observed in presymptomatic and early symptomatic ADAD generalize to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgments

The study sponsors had no role in any aspects of designing or executing this study. The authors had full access to the data used in the study and made the final decision to submit for publication. Data collection and sharing for this project was supported by the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN, U19AG032438), funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Queen Square Dementia Biomedical Research Unit, the Alzheimer’s Society (AS-PG-205), and the Medical Research Council’s (MRC) Dementias Platform UK (DPUK). The present study was undertaken at UCLH/UCL, who received a proportion of funding from the Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centre’s funding scheme. The Dementia Research Centre (DRC) is supported by the UK Dementia Research Institute, Alzheimer’s Research UK (ARUK), Brain Research Trust, and The Wolfson Foundation. The DRC is also an ARUK coordinating centre and has received equipment funded by ARUK and the Brain Research Trust. K.M.K. reports grants from Anonymous Foundation, during the conduct of the study; grants from ARUK (ARUK-PCRF2014B-1), outside the submitted work. D.M.C. reports grants from Anonymous Foundation and the Alzheimer’s Society (AS-PG-15-025), during the conduct of the study; grants from Anonymous Foundation, Alzheimer’s Research UK, and Medical Research Council outside the submitted work. CF received a grant from the Institute of Neurology, UCL that funded the work reported here. He also reports grants from NIHR, the Economic and Social Research Council, Effective Intervention, the Multiple Sclerosis Trials Collaboration and Oxford University, and consultancy payments from CSL Behring, all for work unrelated to this paper. T.L.S.B. reports grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U19AG032438, UL1TR000448, and 5P30NS04805), during the conduct of the study; grants from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (Eli Lilly), other from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (Eli Lilly), other from Roche, other from Medscape LLC, and other from Quintiles, outside the submitted work. J.C.M. reports grants from NIH (P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276, and U19AG032438), during the conduct of the study. M.N.R. reports personal fees from Servier, grants from National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), DIAN, GENFI, and DPUK, outside the submitted work. N.C.F. reports personal fees (all paid to University College London directly) from Janssen/Pfizer, GE Health-care, IXICO, Johnson & Johnson, Genzyme, Eisai, Janssen Alzheimer’s Immunotherapy Research and Development, Lilly Research Laboratories (AVID) and Eli Lilly, and Novartis Pharma AG, outside the submitted work. In addition, N.C.F. has a patent QA Box issued. R.J.B. reports grants from NIH/NIA U19 AG032438 and Anonymous Foundation, during the conduct of the study; grants from the Alzheimer’s Association, American Academy of Neurology, Anonymous Foundation, AstraZeneca, BrightFocus Foundation, Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, Merck, Metropolitan Life Foundation, NIH, grants from Pharma Consortium (Biogen Idec, Elan Pharmaceuticals Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Hoffman La-Roche Inc., Genentech Inc., Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, Mithridion Inc., Novartis Pharma AG, Pfizer Biotherapeutics R and D, Sanofi-Aventi, and Eisai), Roche, Ruth K. Broadman Biomedical Research Foundation, NIH/NINDS 2R01NS065667-05, Alzheimer’s Association, NIH/NIA (5K23AG030946, P50AG05681), nonfinancial support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, other from C2N Diagnostics, NIH and NIH/State Government Sources, personal fees and other from Washington University, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Roche, IMI, Sanofi, Global Alzheimer’s Platform, FORUM, OECD, and Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Merck, outside the submitted work. S.S. reports grants and personal fees from Lilly, Biogen, Genentech, Roche, and Merck, personal fees from Piramal and Forum, grants from GE and Avid, outside the submitted work. A.G. reports grants from NIH and Anonymous Foundation, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Cognition Therapeutics and Amgen, grants and nonfinancial support from Genentech, grants from DIAN Pharma Consortium, outside the submitted work. In addition, A.G. has a patent (6,083,694, 5,973,133) issued. R.A.S. reports grants from National Institute on Aging, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, American Health Assistance Foundation, and Alzheimer’s Association, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Eisa, Merck, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, Roche, Isis, Janssen, Biogen, and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. A.M.B. reports grants from NIH (AG034189, AG043337, AG016495, AG036469, AG037212), during the conduct of study; personal fees from Keystone Heart, personal fees from ProPhase, outside the submitted work. M.R.F., B.G., and A.J.S. were supported by NIH grant P30 AG010133 during the study; A.J.S. was supported by additional NIH grants (R01 AG019771, R01 LM011360, R44 AG049540, R01 CA129769, and U01 AG032984) during the conduct of the study, and also received grant support from Eli Lilly and PET tracer support from Avid Radio-pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. C.R.J. reports grants from NIH, Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease professorship of the Mayo Foundation, other from Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work. PRS reports grants from NIA, Anonymous Foundation, and Wicking and Mason Trusts, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from ICMI Speakers & Entertainers and Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd, outside the submitted work. M.W.W. reports grants from DOD, NIH/NIA, Veterans Administration, Alzheimer’s Association, and Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Synarc, Janssen, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Neurotrope Bioscience, Merck, Avid, Biogen Idec, Genentech, and Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work. J.M.R. reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study; other from Biogen Idec, other from Eli-Lilly, outside the submitted work. All other authors have nothing to disclose. C.C.R. reports personal fees from Roche and GE Healthcare, grants from GE Healthcare, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and Piramal Imaging, outside the submitted work. S.O. is funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/H046410/1, EP/J020990/1, EP/K005278), the Medical Research Council (MR/J01107X/1), the EU-FP7 project VPH-DARE@IT (FP7- ICT-2011-9-601055), and the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR BRC UCLH/UCL High Impact Initiative BW.mn.BRC10269.

We gratefully acknowledge the altruism of the participants and their families and the contributions of the DIAN research and support staff at each of the participating sites. In addition, Shona Clegg, Casper Nielsen, Felix Woodward, Emily Manning, Elizabeth Gordon, and Josephine Barnes from the Dementia Research Centre assisted with the quality control of automated segmentation and coregistration of regions for longitudinal analysis. Cono Ariti and James Henry Roger from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine assisted with SAS coding. All authors reviewed the manuscript critically for scientific content and approved the final draft before it was submitted for publication. DIAN Study investigators reviewed the manuscript for consistency of data interpretation with previous DIAN Study publications.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.2268.

References

- 1.Golde TE, Schneider LS, Koo EH. Anti-aβ therapeutics in Alzheimer’s disease: the need for a paradigm shift. Neuron. 2011;69:203–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan NS, Rossor MN. Correlating familial Alzheimer’s disease gene mutations with clinical phenotype. Biomark Med. 2010;4:99–112. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryman DC, Acosta-Baena N, Aisen PS, Bird T, Danek A, Fox NC, et al. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;83:253–60. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–16. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cash DM, Rohrer JD, Ryan NS, Ourselin S, Fox NC. Imaging endpoints for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6:87. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0087-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benzinger TL, Blazey T, Jack CR, Koeppe RA, Su Y, Xiong C, et al. Regional variability of imaging biomarkers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4502–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317918110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yau WY, Tudorascu DL, McDade EM, Ikonomovic S, James JA, Minhas D, et al. Longitudinal assessment of neuroimaging and clinical markers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:804–13. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00135-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JC, Aisen PS, Bateman RJ, Benzinger TL, Cairns NJ, Fagan AM, et al. Developing an international network for Alzheimer research: the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Clin Investig (Lond) 2012;2:975–84. doi: 10.4155/cli.12.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Borowski BJ, Gunter JL, Fox NC, Thompson PM, et al. Update on the magnetic resonance imaging core of the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:212–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17:87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung KK, Barnes J, Modat M, Ridgway GR, Bartlett JW, Fox NC, et al. Brain MAPS: an automated, accurate and robust brain extraction technique using a template library. Neuroimage. 2011;55:1091–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardoso MJ, Leung K, Modat M, Keihaninejad S, Cash DM, Barnes J, et al. STEPS: Similarity and Truth Estimation for Propagated Segmentations and its application to hippocampal segmentation and brain parcelation. Med Image Anal. 2013;17:671–84. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modat M, Ridgway GR, Taylor ZA, Lehmann M, Barnes J, Hawkes DJ, et al. Fast free-form deformation using graphics processing units. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2010;98:278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malone IB, Leung KK, Clegg S, Barnes J, Whitwell JL, Ashburner J, et al. Accurate automatic estimation of total intracranial volume: a nuisance variable with less nuisance. Neuroimage. 2015;104:366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung KK, Ridgway GR, Ourselin S, Fox NC. Consistent multi-time-point brain atrophy estimation from the boundary shift integral. Neuroimage. 2012;59:3995–4005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung KK, Clarkson MJ, Bartlett JW, Clegg S, Jack CR, Weiner MW, et al. Robust atrophy rate measurement in Alzheimer’s disease using multi-site serial MRI: tissue-specific intensity normalization and parameter selection. Neuroimage. 2010;50:516–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung KK, Barnes J, Ridgway GR, Bartlett JW, Clarkson MJ, Macdonald K, et al. Automated cross-sectional and longitudinal hippocampal volume measurement in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2010;51:1345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeborough PA, Fox NC. The boundary shift integral: an accurate and robust measure of cerebral volume changes from registered repeat MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1997;16:623–9. doi: 10.1109/42.640753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, Cummings J, DeCarli C, Ferris S, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:210–6. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Den Hout A, Muniz-Terrera G, Matthews FE. Smooth random change point models. Stat Med. 2011;30:599–610. doi: 10.1002/sim.4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall CB, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M, Stewart WF. A change point model for estimating the onset of cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Stat Med. 2000;19:1555–66. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1555::aid-sim445>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall CB, Ying J, Kuo L, Lipton RB. Bayesian and profile likelihood change point methods for modeling cognitive function over time. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2003;42:91–109. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost C, Kenward MG, Fox NC. The analysis of repeated “direct” measures of change illustrated with an application in longitudinal imaging. Stat Med. 2004;23:3275–86. doi: 10.1002/sim.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyslop T. SAS Macros for Bootstrap Samples With Stratification and Multiple Observations Per Subject. Washington DC. Presented at the Northeast SAS Users Group; October 8–10, 1995; pp. 805–12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barker NA. Practical Introduction to the Bootstrap Using the SAS System. Heidelberg, Germany. Presented at the Pharmaceutical Users Software Exchange (PhUSE), Statistics and Pharmacokinetics section; October 10–12, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Den Hout A, Muniz-Terrera G, Matthews FE. Change point models for cognitive tests using semi-parametric maximum likelihood. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2013;57:684–98. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson NE, Moore MM, Dame A, Howieson D, Silbert LC, Quinn JF, et al. Trajectories of brain loss in aging and the development of cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2008;70:828–33. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000280577.43413.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Younes L, Albert M, Miller MI. Inferring changepoint times of medial temporal lobe morphometric change in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;5:178–87. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridha BH, Barnes J, Bartlett JW, Godbolt A, Pepple T, Rossor MN, et al. Tracking atrophy progression in familial Alzheimer’s disease: a serial MRI study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:828–34. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70550-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knight WD, Kim LG, Douiri A, Frost C, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Acceleration of cortical thinning in familial Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1765–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Westlye LT, Østby Y, Tamnes CK, Jernigan TL, et al. When does brain aging accelerate? Dangers of quadratic fits in cross-sectional studies. Neuroimage. 2010;50:1376–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen JS, Bruss J, Brown CK, Damasio H. Normal neuroanatomical variation due to age: the major lobes and a parcellation of the temporal region. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1245–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fraser MA, Shaw ME, Cherbuin N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal hippocampal atrophy in healthy human ageing. Neuroimage. 2015;112:364–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walhovd KB, Westlye LT, Amlien I, Espeseth T, Reinvang I, Raz N, et al. Consistent neuroanatomical age-related volume differences across multiple samples. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:916–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quiroz YT, Stern CE, Reiman EM, Brickhouse M, Ruiz A, Sperling RA, et al. Cortical atrophy in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease presenilin 1 mutation carriers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:556–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleisher AS, Chen K, Quiroz YT, Jakimovich LJ, Gutierrez Gomez M, Langois CM, et al. Associations between biomarkers and age in the presenilin 1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease kindred. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:316. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sala-Llonch R, Lladó A, Fortea J, Bosch B, Antonell A, Balasa M, et al. Evolving brain structural changes in PSEN1 mutation carriers. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1261–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weston PS, Nicholas JM, Lehmann M, Ryan NS, Liang Y, Macpherson K, et al. Presymptomatic cortical thinning in familial Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal MRI study. Neurology. 2016;87:2050–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storandt M, Balota DA, Aschenbrenner AJ, Morris JC. Clinical and psychological characteristics of the initial cohort of the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) Neuropsychology. 2014;28:19–29. doi: 10.1037/neu0000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bateman RJ, Benzinger TL, Berry S, Clifford DB, Duggan C, Fagan AM, et al. The DIAN-TU Next Generation Alzheimer’s prevention trial: adaptive design and disease progression model. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cash DM, Ridgway GR, Liang Y, Ryan NS, Kinnunen KM, Yeatman T, et al. The pattern of atrophy in familial Alzheimer disease: volumetric MRI results from the DIAN study. Neurology. 2013;81:1425–33. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a841c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.