ABSTRACT

Purpose: To determine the local government area (LGA)-level prevalence of trachoma in all 34 LGAs of Katsina State.

Methods: A population-based prevalence survey was conducted in each LGA of Katsina State, using the Global Trachoma Mapping Project methodology. We used a 3-stage cluster random sampling strategy to select 25 households from each of 25 clusters. We examined all residents of selected households aged 1 year and older for the clinical signs of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF), trachomatous inflammation–intense and trichiasis, using the World Health Organization (WHO) simplified grading scheme.

Results: We examined 129,281 persons. Six LGAs had a TF prevalence ≥10%, and another six LGAs had a TF prevalence between 5% and 9.9%; all 12 require mass drug administration with azithromycin plus other interventions. The prevalence of trichiasis was ≥1.0% in 13 LGAs, and there is a need to perform trichiasis surgery in over 26,000 persons to reach targets set by the WHO for elimination of trichiasis.

Conclusion: The prevalence of TF is generally low in Katsina state, but urgent steps must be taken to implement the full SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, environmental improvement) in at least 12 LGAs while also stepping up efforts to provide community-based trichiasis surgery throughout the whole state, in order to make trachoma elimination by 2020 a reality.

KEYWORDS: Blindness, mass drug administration, SAFE strategy, trachoma prevalence, trichiasis

Introduction

Trachoma, caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, is spread by direct contact with ocular and nasal discharges from infected persons, by contact with fomites, and by eye-seeking muscid flies. Recurrent infections can result in scarring of the conjunctivae and inward turning of the eyelashes, which scratch the eyeball. This condition, referred to as trachomatous trichiasis, is painful and when untreated may lead to trachomatous corneal opacification, an irreversible cause of visual impairment.

Blindness from trachoma can be avoided by implementation of the SAFE strategy (surgery for trichiasis, antibiotics to clear infection, and promotion of facial cleanliness and environmental improvement to reduce transmission). The SAFE strategy is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO)1 for elimination of trachoma as a public health problem.2 Considerable successes have been reported with this strategy.3–6

In Katsina State, Nigeria, trachoma was last documented about 10 years ago7,8 in 10 local government areas (LGAs). Those data suggested that five LGAs required at least three years’ implementation of the full SAFE strategy and the other five required at least 1 year’s implementation.8 LGAs are the normal administrative units for health care management in Nigeria, and therefore the appropriate choice as the local equivalent of the WHO-defined “district” for trachoma elimination.9,10 However, LGA-level prevalence data have not been available for the whole state, and as a result, the SAFE strategy has not yet been fully deployed in Katsina State.

This work aimed to provide the data required for planning SAFE strategy implementation throughout Katsina State, by conducting a population-based trachoma prevalence survey in each of the state’s 34 LGAs.

Materials and methods

Sample size calculation, pre-survey field team training and certification, and data collection techniques all followed the standard Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) protocols, as described elsewhere.11 LGAs were used as evaluation units. We selected 25 clusters of 25 households in each LGA, expecting to find a mean of just over two children aged 1–9 years per household. This put 1250 children in the sampling frame per LGA. Allowing for 20% non-response, we anticipated being able to recruit the minimum sample size of 1019 children aged 1–9 years in each LGA using this approach.

Ethics

Protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (reference 6319), the National Health Research Ethics Committee of Nigeria (reference NHREC/01/01/2007), and the Katsina State Ministry of Health ethics subcommittee. The Katsina State Ministry of Health also gave administrative permission to conduct the surveys. Field teams explained the examination protocol to each adult in a language they understood. Since most study subjects could neither read nor write, only verbal consent for enrolment and examination was obtained. The head of the household gave consent for the participation of minors and adults gave consent for their own participation. Consent was documented in an Open Data Kit-based Android smartphone application (LINKS)11 by research teams. Individuals with active trachoma were given two tubes of 1% tetracycline eye ointment together with instructions for its use, and persons with trichiasis were referred for lid surgery at the nearest facility with trained trichiasis surgeons.

Sampling

We used a 3-stage cluster sampling strategy to select the survey population in each LGA. Villages (with populations between 13,000 and 16,000 people) were used as first stage clusters and 25 villages were selected from a list of all the villages in each LGA, using a probability-proportional-to-size technique. Each selected village’s (pre-existing) administrative units, which were of approximately equal size (mean 4500 people), were listed, and one of these units was selected at random. In selected units, 25 households were required, with a household defined as all the individuals normally resident in the compound eating from the same pot. All persons older than 1 year of age in selected households were invited to participate. Because security in northern Nigeria was somewhat tenuous at the time of survey planning and implementation, use of a household selection method already familiar to the population was felt to be critical to field team safety, so the random walk approach was used despite its epidemiological drawbacks.12–14 A person resident in the village showed the survey team the center of the administrative unit. A pen was spun on the ground at that point and the direction the pen pointed was followed, with households in this direction being selected. Field teams made an effort to return on the same day and examine persons that were absent at the first visit.

Survey definitions

We used the WHO simplified grading scheme.15 Teams examined participants for the presence of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF), trachomatous inflammation–intense, and trichiasis. In eyes with trichiasis, we did not record the presence or absence of trachomatous conjunctival scarring, so in this manuscript we are only able to talk about trichiasis, rather than trachomatous trichiasis. We have reported the prevalence of TF in 1–9-year-olds and the prevalence of trichiasis in persons aged 15 years and older as our primary outcome measures for disease elimination planning purposes. Data on household-level access to water and sanitation were collected using standard GTMP protocols.11

Data analysis

As described previously, data were cleaned by the GTMP data manager (RW) and analyzed using pre-specified algorithms to control for age and sex of those recruited, and the number of individuals examined in each cluster11. The trichiasis backlog in each LGA was calculated by multiplying the prevalence estimate in persons aged 15 years and older by 56% of the total population in the LGA (as determined in the most recent census), because 56% of the Nigerian population is 15 years and older.16

Results

We examined a total of 129,281 persons in Katsina State between March and June 2014. The ages of participants ranged from 1 year to over 100 years. More females (69,961; 54.1%) were examined than males (59,320; 45.9%). The age and sex distributions of participants for the state as a whole are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of participants, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Katsina State, Nigeria, 2014.

| Age group (years) |

Female, n (%) | Male, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 31,835 (49.3) | 32,685 (50.7) | 64,520 (49.9) |

| 11–20 | 9,961 (59.1) | 6900 (40.9) | 16,861 (13.0) |

| 21–30 | 10,852 (76.9) | 3261 (23.1) | 14,113 (10.9) |

| 31–40 | 7766 (64.6) | 4256 (35.4) | 12,022 (9.3) |

| 41–50 | 4631 (50.0) | 4638 (50.0) | 9269 (7.2) |

| 51–60 | 2598 (41.2) | 3710 (58.8) | 6308 (4.9) |

| 61–70 | 1496 (37.8) | 2465 (62.2) | 3961 (3.1) |

| 71–80 | 637 (37.3) | 1071 (62.7) | 1708 (1.3) |

| 81+ | 185 (35.6) | 334 (64.4) | 519 (0.4) |

| Total | 69,961 (54.1) | 59,320 (45.9) | 129,281 (100.0) |

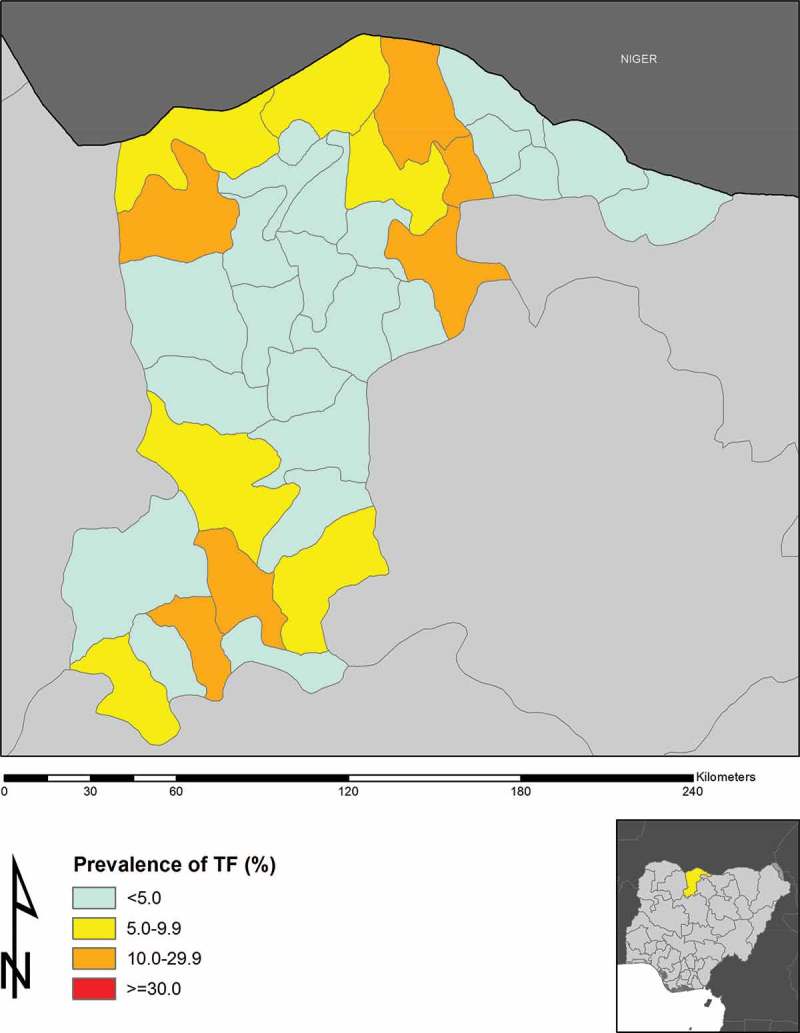

A total of 59,971 children aged 1–9 years were examined; 30,351 (50.6%) were male and 29,620 (49.4%) were female. State-wide, the prevalence of TF in this age group was 4.9% (95% confidence interval, CI, 4.7–5.1%). The prevalence in girls (4.8%, 95% CI 4.6–5.1%) was lower than in boys (4.9%, 95% CI 4.7–5.2%), but there was no statistically significant difference in TF prevalence between the sexes (odds ratio, OR, 1.02, 95% CI 0.95–1.10; χ2 = 0.41, p = 0.52). The LGA-level age-adjusted prevalences of TF in 1–9-year-olds ranged from 0.0–29.5% (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Local government area (LGA)-level prevalence of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) and trichiasis, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Katsina State, Nigeria, 2014.

| LGA | Age-adjusted TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds, % (95% CI) | Age- and sex-adjusted trichiasis prevalence in those ≥15 years, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Bakori | 29.5 (25.5–34.6) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

| Batagarawa | 4.7 (3.5–6.2) | 1.7 (1.1–2.4) |

| Batsari | 13.5 (7.6–18.9) | 1.7 (1.1–2.2) |

| Baure | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 3.6 (2.6–4.6) |

| Bindawa | 4.4 (3.5–5.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) |

| Charanchi | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) |

| Dan Musa | 3.2 (2.5–3.9) | 0.4 (0.1–0.7) |

| Dandume | 1.6 (0.6–3.3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) |

| Danja | 3.1 (1.9–4.2) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) |

| Daura | 2.4 (1.5–3.4) | 2.7 (1.5–4.4) |

| Dutsi | 11.3 (8.7–13.6) | 1.9 (1.0–2.9) |

| Dutsin Ma | 1.5 (0.6–2.7) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) |

| Faskari | 1.1 (0.5–1.8) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

| Funtua | 10.7 (7.0–15.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) |

| Ingawa | 12.2 (8.2–17.2) | 1.4 (0.9–1.9) |

| Jibia | 5.1 (4.0–6.5) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) |

| Kafur | 7.0 (5.4–8.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) |

| Kaita | 9.8 (6.4–13.6) | 1.1 (0.5–1.8) |

| Kankara | 6.3 (4.4–8.0) | 0.7 (0.3–1.2) |

| Kankia | 4.2 (2.7–6.2) | 0.7 (0.2–1.2) |

| Katsina | 4.4 (3.3–5.7) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) |

| Kurfi | 3.3 (1.8–4.8) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) |

| Kusada | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.0 (0.5–1.7) |

| Mai’Adua | 4.5 (3.0–6.5) | 3.0 (1.8–4.6) |

| Malumfashi | 0.5 (0.1–0.9) | 0.3 (0.0–0.9) |

| Mani | 8.1 (6.5–9.9) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) |

| Mashi | 15.4 (10.9–21.5) | 1.2 (0.7–1.8) |

| Matazu | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.6 (0.2–1.1) |

| Musawa | 1.5 (0.1–4.1) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) |

| Rimi | 0.2 (0.0–0.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) |

| Sabuwa | 9.6 (6.8–12.4) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) |

| Safana | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 1.7 (1.1–2.2) |

| Sandamu | 2.4 (0.9–4.2) | 1.6 (0.8–2.3) |

| Zango | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) | 2.6 (1.7–3.8) |

CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of active trachoma (trachomatous inflammation–follicular, TF) in 1–9-years-olds in Katsina State, Nigeria, 2014.

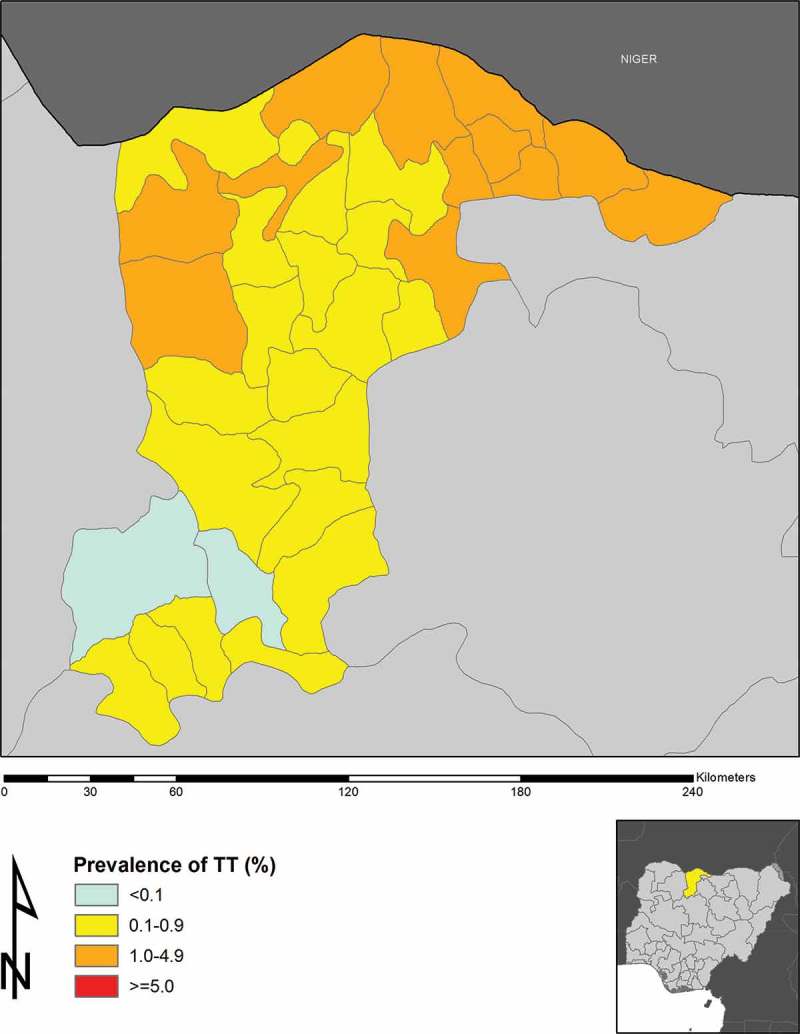

We examined 56,156 persons aged 15 years and older; 22,607 (40.3%) were male and 33,549 (59.7%) were female. The state-wide prevalence of trichiasis was 1.8% (95% CI 1.7–1.9%) in this age group. The trichiasis prevalence in adult females (2.1%, 95% CI 1.9–2.2%) was greater than in adult males (1.4%, 95% CI 1.3–1.6%), this difference was statistically significant, with an OR of 1.4 (95% CI 1.1–1.6; χ2 = 37.5, p = 0.0005). The LGA-level age- and sex-adjusted prevalences of trichiasis in adults ranged from 0.0–3.6% (Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of trichiasis in ≥15-year-olds in Katsina State, Nigeria, 2014.

Six LGAs (Bakori, Batsari, Dutsi, Funtua, Ingawa, and Mashi) in Katsina State had TF prevalences ≥10%, with another six LGAs (Jibia, Kafur, Kaita, Kankara, Mani, and Sabuwa) had TF prevalences between 5% and 9.9%. The prevalence of trichiasis was ≥1% in 13 LGAs (Batagarawa, Batsari, Baure, Daura, Dutsi, Ingawa, Kaita, Kusada, Mai’ Adua, Mashi, Safana, Sandamu, and Zango). Given the estimated population of Katsina State is 5,801,584,16 there is therefore an estimated trichiasis backlog of 32,335 persons; ignoring incident trichiasis, 26,258 people need to be offered trichiasis surgery to achieve the trichiasis prevalence criterion for elimination of trachoma as a public health problem17 in every Katsina State LGA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Local government area (LGA)-level estimates of trichiasis surgery backlog, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Katsina State, Nigeria, 2014.

| LGA | Estimated total population | Trichiasis prevalence in persons aged ≥15 years, % | Estimated trichiasis backlog, n | People to be offered trichiasis surgery to achieve the trichiasis component of “elimination of trachoma as a public health problem”, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakori | 149,516 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Batagarawa | 189,059 | 1.7 | 1849 | 1637 |

| Batsari | 207,874 | 1.7 | 2003 | 1770 |

| Baure | 202,941 | 3.6 | 4038 | 3811 |

| Bindawa | 151,002 | 0.3 | 245 | 76 |

| Charanchi | 136,989 | 0.2 | 122 | 0 |

| Dan Musa | 113,190 | 0.4 | 229 | 102 |

| Dandume | 145,323 | 0.3 | 226 | 63 |

| Danja | 125,481 | 0.3 | 195 | 54 |

| Daura | 224,884 | 2.7 | 3448 | 3196 |

| Dutsi | 120,902 | 1.9 | 1266 | 1131 |

| Dutsin Ma | 169,829 | 0.7 | 671 | 481 |

| Faskari | 194,400 | 0.0 | 9 | 0 |

| Funtua | 225,156 | 0.2 | 250 | 0 |

| Ingawa | 169,148 | 1.4 | 1297 | 1107 |

| Jibia | 167,435 | 0.6 | 572 | 384 |

| Kafur | 209,360 | 0.2 | 264 | 30 |

| Kaita | 182,405 | 1.1 | 1073 | 868 |

| Kankara | 243,259 | 0.7 | 905 | 632 |

| Kankia | 151,395 | 0.7 | 609 | 440 |

| Katsina | 318,132 | 0.3 | 604 | 247 |

| Kurfi | 116,700 | 0.4 | 241 | 110 |

| Kusada | 98,348 | 1.0 | 546 | 435 |

| Mai’Adua | 201,800 | 3.0 | 3373 | 3147 |

| Malumfashi | 182,891 | 0.3 | 354 | 149 |

| Mani | 176,301 | 0.3 | 301 | 104 |

| Mashi | 171,070 | 1.2 | 1156 | 965 |

| Matazu | 113,814 | 0.6 | 371 | 243 |

| Musawa | 170,006 | 0.3 | 294 | 103 |

| Rimi | 154,092 | 0.2 | 161 | 0 |

| Sabuwa | 140,679 | 0.5 | 428 | 271 |

| Safana | 185,207 | 1.7 | 1756 | 1549 |

| Sandamu | 136,944 | 1.6 | 1189 | 1036 |

| Zango | 156,052 | 2.6 | 2291 | 2117 |

| Total | 5,801,584 | 32,335 | 26,258 |

Across LGAs, the proportion of households that had access to water for hygiene purposes within 1 km of the location of the house ranged from 24% to 100%. Similarly, proximate access to improved water for hygiene purposes was as low as 10% in three LGAs. Over 80% of households had proximate access to improved washing water in only two LGAs. Access to improved latrines ranged from 1% to 100%, but only four of the 34 LGAs had >80% access to improved latrines (Table 4).

Table 4.

Household access to wash water and improved latrines, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Katsina State, Nigeria, 2014.

| LGA | Wash water access <1 km, % | Improved wash water access <1 km, % | Improved latrine access, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bakori | 69.2 | 43.0 | 34.3 |

| Batagarawa | 93.1 | 33.9 | 41.0 |

| Batsari | 51.6 | 31.9 | 18.0 |

| Baure | 39.0 | 48.1 | 30.1 |

| Bindawa | 71.0 | 46.5 | 10.4 |

| Charanchi | 65.7 | 45.7 | 9.8 |

| Dan Musa | 98.1 | 11.2 | 9.8 |

| Dandume | 99.5 | 33.9 | 64.6 |

| Danja | 73.7 | 50.7 | 55.5 |

| Daura | 71.5 | 10.8 | 71.9 |

| Dutsi | 52.4 | 10.4 | 57.1 |

| Dutsin Ma | 76.4 | 53.8 | 29.4 |

| Faskari | 65.3 | 26.9 | 30.1 |

| Funtua | 100.0 | 96.4 | 44.5 |

| Ingawa | 49.9 | 33.0 | 29.1 |

| Jibia | 80.2 | 30.1 | 27.7 |

| Kafur | 86.9 | 29.6 | 100.0 |

| Kaita | 49.2 | 61.2 | 9.7 |

| Kankara | 82.7 | 35.6 | 95.0 |

| Kankia | 49.1 | 48.1 | 16.7 |

| Katsina | 95.3 | 18.1 | 88.7 |

| Kurfi | 52.4 | 46.9 | 16.1 |

| Kusada | 66.7 | 71.5 | 21.3 |

| Mai’Adua | 24.0 | 28.6 | 34.4 |

| Malumfashi | 93.9 | 57.0 | 47.8 |

| Mani | 43.3 | 50.6 | 25.0 |

| Mashi | 83.8 | 17.4 | 15.0 |

| Matazu | 62.6 | 62.8 | 25.6 |

| Musawa | 65.3 | 60.2 | 28.0 |

| Rimi | 67.8 | 57.1 | 42.4 |

| Sabuwa | 95.8 | 95.8 | 1.4 |

| Safana | 65.9 | 38.3 | 11.3 |

| Sandamu | 66.0 | 10.2 | 65.0 |

| Zango | 49.8 | 49.8 | 81.6 |

Various aspects of the SAFE strategy will need to be implemented in each LGA to be able to attain the elimination thresholds recommended by WHO (Table 5).

Table 5.

SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, environmental improvement) activities required to be implemented to eliminate trachoma in each local government area (LGA) of Katsina State, Nigeria, 2014.

| LGA | Action for surgery (S) required | Action for A, F, and E required |

|---|---|---|

| Bakori | Facility-based TT S | Implementation of AFE for at least 3 years before impact assessment |

| Batagarawa | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Batsari | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Implementation of AFE for at least 3 years before impact assessment |

| Baure | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Bindawa | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Charanchi | Facility-based TT S | Continued F and E activities |

| Dan Musa | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Dandume | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Danja | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Daura | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Dutsi | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Implementation of AFE for at least 3 years before impact assessment |

| Dutsin Ma | Lower priority for implementation of S | Continued F and E activities |

| Faskari | Facility-based TT S | Continued F and E activities |

| Funtua | Facility-based TT S | Implementation of AFE for at least 3 years before impact assessment |

| Ingawa | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Implementation of AFE for at least 3 years before impact assessment |

| Jibia | Lower priority for implementation of S | Implementation of AFE for at least 1 year before impact assessment |

| Kafur | Facility-based TT S | Implementation of AFE for at least 1 year before impact assessment |

| Kaita | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Implementation of AFE for at least 1 year before impact assessment |

| Kankara | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Implementation of AFE for at least 1 year before impact assessment |

| Kankia | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Katsina | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Kurfi | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Kusada | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Mai’Adua | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Malumfashi | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Mani | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Implementation of AFE for at least 1 year before impact assessment |

| Mashi | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Implementation of AFE for at least 3 years before impact assessment |

| Matazu | Lower priority for implementation of community based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Musawa | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Rimi | Facility-based TT S | Continued F and E activities. |

| Sabuwa | Lower priority for implementation of community-based S | Implementation of AFE for at least 1 year before impact assessment |

| Safana | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Sandamu | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

| Zango | High priority for implementation of community-based S | Continued F and E activities |

TT, trachomatous trichiasis.

Discussion

In Katsina State, trachoma is still a public health problem. Bakori, Batsari, Dutsi, Funtua, Ingawa and Mashi LGAs had TF prevalences in 1–9-year-olds between 10% and 29.9%, and therefore qualify for azithromycin mass drug administration (MDA) plus implementation of the F and E components of the SAFE strategy, for an initial period of 3 years, as recommended by WHO.10 Another six LGAs had TF prevalences between 5% and 9.9% and may benefit from at least one round of MDA in addition to the F and E components of SAFE.18 All but two of six LGAs with TF prevalences ≥10% had <80% household-level access to a proximate washing water supply, and none had ≥80% household-level access to improved latrine facilities. Some LGAs had very low prevalence of access to improved latrines, and this seemed to mirror higher prevalences of TF. The proportion of households using improved washing water in these LGAs was generally extremely low, starting from 9%. Funtua was the exception, with good reported access to water for washing, but the population in this LGA had poor access to improved latrines; all other LGAs with TF ≥10% also had poor access to improved latrines. Full implementation of the SAFE strategy in Katsina State will require a particular focus on provision of improved water and sanitation facilities. In addition to providing the hardware, communities will need to be educated on the relationship between trachoma blindness, and water and sanitation, with an emphasis on the need for facial cleanliness and appropriate disposal of solid human waste.

The LGA of Kaita had a relatively low (9.8%) TF prevalence, indicating the need for intervention with only one year of MDA, but had a significant trichiasis burden, with an estimated trichiasis prevalence in adults of 1.1%. This would be consistent with the view that trachoma is disappearing from this LGA, as previously suggested.7 In two previous surveys, Kaita was found to have a high prevalence of both TF and trichiasis.7,8

A total of 10 LGAs in Katsina State participated in population-based trachoma prevalence surveys in 2005, using comparable methodologies to those outlined here.7 For five of those 10, the results of the current round of surveys are similar to those obtained in 2005. For Baure, Kaita, Mai Adua, and Zango, however, the 2005 work suggested that three or more rounds of azithromycin MDA was needed, while the current data indicate that either a single round should be attempted (Kaita) or that (for the other four LGAs), implementation of the A, F and E components of SAFE is not a priority. Access to water and sanitation facilities has remained essentially the same in these LGAs in the 10-year interval between surveys, and trachoma elimination interventions have not been undertaken. We therefore attribute the apparent falls in the prevalence of TF to general socioeconomic development, or changes in population dynamics. Part of the rationale for repeating the prevalence estimates in already-surveyed areas of Katsina was the impression within government that living conditions have improved, and that therefore the scale of interventions against trachoma required could be smaller than might have been previously planned. Those suspicions about the reduction in the prevalence of TF and the scale of interventions required appear to have been borne out.

Katsina State has a trichiasis backlog of over 31,000 people needing surgery. Trichiasis prevalence is >1% in adults in 13 LGAs (Batagarawa, Batsari, Baure, Daura, Dutsi, Ingawa, Kaita, Kusada, Mai’ Adua, Mashi, Safana, Sandamu, and Zango). Ignoring incident trichiasis, over 26,000 individuals will need to be offered trichiasis surgery in Katsina State in order to eliminate trachoma throughout the state. With only seven active trichiasis surgeons living in the state, this presents a considerable challenge. There is clearly a need for more trained surgeons; this should be achieved through an organized local training and certification program for active eye nurses.19 Once trained, there is a need to ensure that each nurse is properly equipped, incentivized, deployed and supervised. Katsina State will require at least 15 lid surgeons performing at least 10 trichiasis surgeries weekly to be able to attain the elimination target for trichiasis by the year 2020 or earlier. In rolling out a trichiasis program in Katsina State, priority needs to be given to Baure, Daura, Mai’Adua, and Zango LGAs, where the prevalence of trichiasis is higher compared to the other LGAs.

For the SAFE strategy to succeed in Katsina State, expansion of trichiasis surgery services, rapid implementation of high coverage azithromycin MDA, and provision and appropriate use of sanitation and water services, are required. Early and robust engagement with water and sanitation agencies will be critical, as well as focused efforts to incorporate education on trachoma and its prevention within existing health education campaigns. With less than 5 years to go before the target date for global elimination of trachoma as a public health problem, this work cannot begin too soon.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.

Funding Statement

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. World Health Organization Future Approaches to Trachoma Control Geneva: WHO/PBL/9656; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Assembly Global elimination of blinding trachoma. 51st World Health Assembly, Geneva, 16 May 1998, Resolution WHA51.11; Geneva: World Health Organization, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization Global WHO Alliance for the elimination of blinding trachoma by 2020. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012;87:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization Report of the 17th meeting of the WHO Alliance for the global elimination of blinding trachoma. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ngondi J, Onsarigo A, Matthews F, et al. Effect of 3 years of SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental change) strategy for trachoma control in southern Sudan: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2006;368(9535):589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferriman A. Blinding trachoma almost eliminated from Morocco. BMJ 2001;323(7326):1387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rabiu MM, Abiose A.. Magnitude of trachoma and barriers to uptake of lid surgery in a rural community of northern Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2001;8:181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jip N, King JD, Diallo MO, et al Blinding trachoma in Katsina state, Nigeria: population-based prevalence survey in ten local government areas. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2008;15:294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization Report of the 2nd global scientific meeting on trachoma, Geneva, 25–27 August, 2003. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Solomon AW, Zondervan M, Kuper H, et al. Trachoma control: a guide for program managers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:214–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brogan D, Flagg EW, Deming M, et al. Increasing the accuracy of the Expanded Programme on Immunization’s cluster survey design. Ann Epidemiol 1994;4:302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Turner AG, Magnani RJ, Shuaib M.. A not quite as quick but much cleaner alternative to the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) cluster survey design. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grais RF, Rose AMC, Guthmann JP.. Don’t spin the pen: two alternative methods for second stage sampling in cluster surveys in urban zones. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2007;4:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, et al. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ 1987;65:477–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Population Commission 2006 population and housing census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria: national and state population and housing tables, priority tables (volume 1). Abuja: National Population Commission, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization Report of the 3rd global scientific meeting on trachoma, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, 19–20 July 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization Meeting Report: Technical Consultation on Trachoma Surveillance. Decatur, GA, USA. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Merbs S, Resnikoff S, Kello AB, et al. Trichiasis surgery for trachoma (2nd ed). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]