Abstract

Adolescent decision-making is highly sensitive to input from the social environment. In particular, adult and maternal presence influence adolescents to make safer decisions when encountered with risky scenarios. However, it is currently unknown whether maternal presence confers a greater advantage than mere adult presence in buffering adolescent risk taking. In the current study, 23 adolescents completed a risk-taking task during an fMRI scan in the presence of their mother and an unknown adult. Results reveal that maternal presence elicits greater activation in reward-related neural circuits when making safe decisions but decreased activation following risky choices. Moreover, adolescents evidenced a more immature neural phenotype when making risky choices in the presence of an adult compared to mother, as evidenced by positive functional coupling between the ventral striatum and medial prefrontal cortex. Our results underscore the importance of maternal stimuli in bolstering adolescent decision-making in risky scenarios.

Graphical abstract

The contents of this page will be used as part of the graphical abstract of html only. It will not be published as part of main article. Prior research showed that mothers could influence teens to make safe decisions during a risk taking task, but it was unknown whether this effect was unique to mothers. In this study, we found that maternal presence, compared to that of an unknown adult, uniquely altered adolescent neural circuitry associated with reward processing and social cognition and helped sway their adolescents towards safe decision making. These findings highlight the continued importance of maternal social scaffolding in adolescence.

Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental period marked by remarkably flexible neural systems (Spear, 2000; Casey, 2015; Hauser, Iannaccone, Walitza, Brandeis & Brem, 2015). Theorized to serve an adaptive purpose (Spear, 2011; Hauser et al., 2015), this flexibility renders adolescents highly susceptible to environmental inputs. Accordingly, contextual influences during adolescence possess a powerful capacity to affect adolescent behavior, especially via rapidly developing affective neural systems (Casey, 2015). While past research has traditionally focused on how environmental inputs adversely affect adolescent behavior (e.g. negative peer influence; Chein, Albert, O'Brien, Uckert & Steinberg, 2011), more recent studies have begun to focus on how other types of contextual influences may interact with neural plasticity during adolescence to guide adolescent behavior towards healthy development (see Telzer, 2016). In the current study, we focus on better understanding how social influences, specifically those from one's parents, interact with adolescent neural systems to promote safe decision-making.

Brain development during adolescence is marked by development of affective neural systems involved in approach motivation and reward sensitivity, and pre-frontal regions implicated in inhibitory control (Casey, 2015; Steinberg, 2010; Somerville, Jones & Casey, 2010). The coordination of these two neural systems is associated with adolescent adjustment. Negative functional coupling between subcortical affective regions and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is associated with optimal behavioral outcomes, such as less risky behavior (Qu, Galvan, Fuligni, Lieberman & Telzer, 2015), whereas positive coupling, a more immature neural state, is associated with maladjustment (Gee, Gabard-Durman, Telzer, Humphreys, Goff et al., 2014). Although childhood is marked by immature regulation (i.e. negative functional coupling), it is not characterized by affective hypersensitivity and high frequencies of encountering risky contexts (Casey, 2015; Spear, 2000, 2011). Thus, while adolescents compared to children possess the requisite neural maturity to independently regulate basic emotional responses (Gee et al., 2014), they are still vulnerable under conditions of socioemotional arousal, such as in risky contexts (e.g. Chein et al., 2011).

Frontolimbic connectivity is sensitive to social input such that the regulatory function of prefrontal regions can be enhanced or impaired depending on the presence of parental stimuli (Gee, Humphreys, Flannery, Goff, Telzer et al., 2013, Gee et al., 2014), highlighting that parents play an important role in the regulation of their offspring's emotions (Gee et al., 2014). Indeed, parents can affect their adolescent offspring's impulse control and emotion regulation by means of social scaffolding, such that parents help their children develop skills necessary for proper adult functioning in vulnerable contexts when children do not yet have the requisite developmental maturity to do so (Dahl, 2004). For example, adolescents with more positive parent-adolescent relationship quality show dampened ventral striatum (VS) and modulated PFC activity during risk-taking and cognitive-control tasks (Qu et al., 2015; Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman & Galvan, 2013; McCormick, Qu & Telzer, 2016). Furthermore, adolescents engage in fewer risky decisions in the mere presence of their mothers and display a dampened reward response (indexed by VS activity) following a risky decision under maternal presence (Telzer, Ichien & Qu, 2015). These studies underscore an important role of families in scaffolding adolescent behavior via changes in brain activation, helping to promote healthy adolescent development.

Despite notable advances in understanding how parents help regulate adolescent affective sensitivity, it remains unclear whether the observed effects generalize to other adults. As they transition into adolescence, youth typically detach from their families and spend an increasing amount of time surrounded by adults other than their caregivers (Larson & Richards, 1991), making it necessary to understand whether these individuals may also provide adequate scaffolding. Prior studies incorporating parental presence during risk taking did not include a condition in which another adult was present, making it difficult to determine whether adaptive social scaffolding is unique to familial relationships, or simply due to adult presence. While recent behavioral work has provided evidence that non-parental, unfamiliar adults can adaptively scaffold adolescent decision-making in risky contexts, at least more so than peers (Silva, Chein & Steinberg, 2016), we still do not understand which exerts a greater influence on adolescent decision-making. Because parents remain an important fixture in the lives of adolescents (Tsai, Telzer & Fuligni, 2013), it is likely that parents offer unique contributions in helping regulate their adolescent's emotions during risky scenarios beyond those of another adult.

In the current study, we sought to clarify the role of parental presence compared to that of an unknown adult in providing social scaffolding for adolescents during risk taking. Adolescent participants completed a risk-taking task during an fMRI scan in the presence of their mother and an unknown adult stranger. Behaviorally, we predicted that adolescents would make more safe choices in the presence of their mother than an unknown adult. At the neural level we expected that parental presence, compared to that of an adult, would modulate bottom-up VS activity during risk taking in a manner that promoted safe decision-making such that maternal presence would be associated with heighted activation in the VS following a safe decision and dampened VS activation following a risky decision. Second, we expected parental presence to be associated with relatively more mature neural coupling between the VS and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Prior studies have indicated a developmental switch in functional coupling between the mPFC and the limbic system, such that children show positive coupling (i.e. more immature neural state) whereas adolescents tend to show more negative coupling (i.e. more mature neural state; Gee et al., 2013). Given the sensitivity of this circuit to social influences along with previous research demonstrating that parental stimuli, relative to unknown adults, elicit mature connectivity in children (Gee et al., 2014), we predicted maternal presence to be associated with a more mature pattern of functional coupling, whereas adult presence would be associated with a more immature pattern of functional coupling (i.e. positive connectivity). Lastly, because adolescence is a sensitive period for social cognitive development (Blakemore & Mills, 2014), we also examined brain regions involved in social cognition such as those implicated in the detection of social salience or perspective taking. We expected adolescents to display greater activation in social cognitive networks in the presence of their mothers compared to an unknown adult.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-four adolescents accompanied by their mothers participated in the study. One participant did not complete the brain scan, resulting in a final sample of 23 15-year-old adolescents (Mage = 15.22 years, SD = 0.35; 9 females). Adolescents were from diverse ethnic backgrounds, including White (n = 14), African American (n = 6), Asian (n = 1) and mixed race (n = 2). We decided before the study to collect as many participants as possible in a four-month span, with the goal of recruiting 20–25 participants, consistent with sample sizes of similar studies (e.g. Chein et al., 2011; Gee et al., 2013). Analyses were not conducted until all data had been collected. All participants and their mothers provided written assent and consent, respectively, in accordance with the policies of the Institutional Review Board.

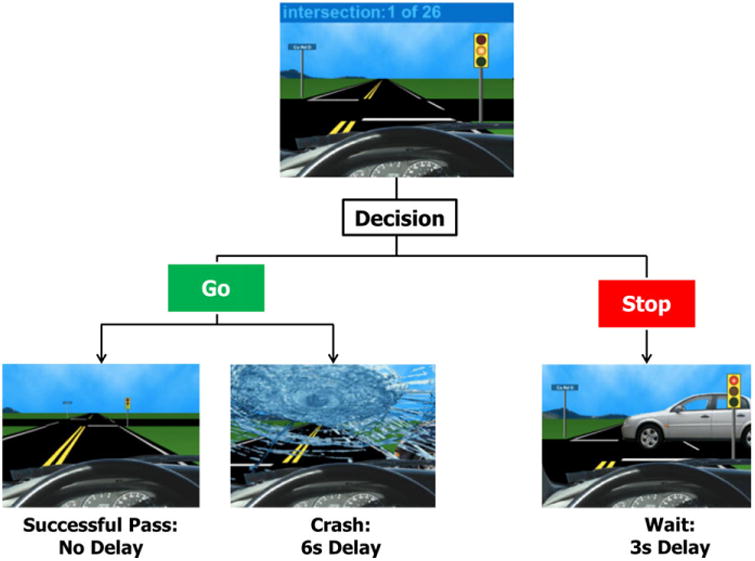

Risk taking paradigm

Adolescents completed the Stoplight Task, a widely utilized and ecologically valid driving simulation used to behaviorally and neurally measure risk taking (Chein et al., 2011). During the task, adolescents took the perspective of a person driving a car and encountered 26 yellow stoplights. At each intersection, adolescents had to make a choice to either (1) brake before the intersection or (2) accelerate through the intersection by pressing one of two buttons. Adolescents were instructed to try to finish the task as quickly as possible in order to earn a larger monetary reward. Accelerating through the intersection (i.e. a ‘go’ decision) resulted in no delay and was thus faster than the decision to brake (i.e. a ‘stop’ decision), which yielded a 3-second delay. However, by choosing to ‘go’ at the intersection, adolescents ran the risk of crashing, resulting in a 6-second delay (Figure 1). Participants had a 30% chance of crashing across the 26 intersections. That is, eight intersections displayed cars approaching the cross roads, resulting in a crash if a decision to ‘go’ was enacted. Participants were not made aware of the probability of crashing. At the behavioral level, risky decision-making was measured as the percentage of trials in which the participant chose to accelerate through the intersection.

Figure 1.

The Stoplight Task. By pressing one of two buttons, adolescents could choose to go through or stop at each yellow light.

Adolescents completed two runs of the Stoplight Task while undergoing functional MRI. During one run, the adolescent's mother was present; another run was completed in which they were told another adult was present. Prior to the run under maternal presence, the adolescent's mother came into the scan control room and was instructed to speak into the intercom and notify their child they were going to watch them for the entire duration of the round. Mothers were instructed to recite a script into the scan intercom (‘Hi [adolescent name], I just wanted to let you know that I'm here and I'll be watching you play this round’) in order to ensure that they would not make any comments that may bias their child's behavior. The mother then stayed in the scan room and observed their child's behavior during the task. Before beginning the run under adult presence, the experimenters informed the participant that an adult, described as a professor who is an expert in adolescent driving behavior, would be observing all participants play one round of the Stoplight Task. The researchers ostensibly called her into the scan room, placed a photo on the screen of the professor so the participant could be ‘introduced to her’, and played a personalized female voice into the scan microphone of the exact same script as the mother condition in order to establish the impression that the adult stranger was present and watching the participant. Upon completion of each scan, the experimenters informed the participant that the respective observer had left the room. The order of conditions was counterbalanced across participants. Participants were trained on how to properly complete the task prior to their brain scan by watching a video of the task and completing two practice runs in order to account for learning effects.

fMRI data acquisition

Neuroimaging data were collected using a 3 Tesla Siemens Trio MRI scanner. Our stoplight task included T2*-weighted echoplanar images (EPI; slice thickness of 3 mm; 38 slices; TRof 2 s; TE of 25 ms; 92 × 92 matrix; FOV of 230 mm; 2.5 × 2.5 × 3 mm3 voxel size). The structural scans consisted of a T2*-weighted, matched-bandwidth (MBW), high resolution, anatomical scan (TR of 4 s; TE of 64 ms; FOVof 230; 192 × 192 matrix; slice thickness of 3 mm; 38 slices) and a T1* magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE; TR of 1.9 s; TE of 2.3 ms; FOV of 230; 256 × 256 matrix; sagittal plane; slice thickness of 1 mm; 192 slices). To maximize brain coverage, the orientation of the MBW and EPI scans were set to be oblique axial.

fMRI data processing and analysis

Neuroimaging data were processed and analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM8; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London, UK). Spatial realignment was conducted in order to correct for head motion (no participant exceeded 2.5 mm of slice-to-slice motion in any direction). Realigned functional data were then coregistered to the high resolution MPRAGE image and were subsequently segmented into cerebrospinal fluid, gray matter, and white matter. The normalization transformation matrix from the segmentation step was applied to the functional and T2 structural images, transforming them into standard stereotactic space as defined by the Montreal Neurological Institute and the International Consortium for Brain Mapping. The normalized functional data were smoothed using an 8 mm Gaussian kernel, full-width-at-half maximum, to increase the signal-to-noise ratio.

Statistical analyses were performed in SPM8 using the general linear model (GLM). Each trial was convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function. High-pass temporal filtering with a cut-off of 128 s was applied to remove low-frequency drift in the time-series. Serial autocorrelations were estimated with a restricted maximum likelihood algorithm with an autoregressive model order of 1. For each participant's fixed-effects analysis, a GLM was created with four regressors of interest for both the adult-present and mother-present conditions. There were two decision regressors (Go and Stop) and three outcome regressors (GoCrash, GoPass and StopPass) per condition. In addition, the wait time after decisions to stop and a final ‘Game Over’ period after each scan were modeled in order to remove them from the implicit baseline. Accordingly, there were 12 total conditions, six for both the mother and adult present runs. Durations for outcomes (e.g. pass or crash) were 1 second. The duration of decision trials constituted the time between when the intersection first appeared and when the participant indicated their response. Pass and wait events had no specific onset times whereas the onset of crash events was that when another car crashed into the participant's car. Crash events happened at most 2 seconds following the yellow light so we modeled the pass and wait events as such, corresponding to the point at which the outcome of a risky decision was clear. Null events were not explicitly modeled, constituting the implicit baseline.

The parameter estimates resulting from the GLM were used to create linear contrast images comparing the conditions of interest. Random effects, group-level analyses were performed on all our individual subject contrasts using GLMFlex. GLMFlex corrects for variance–covariance inequality, partitions error terms, removes outliers and sudden activation changes in the brain, and analyzes all voxels containing data (http://mrtools.mgh.harvard.edu/index.php/GLM_Flex).

We conducted whole-brain t-tests at the group level to examine overall differences in neural activation during the decision phase when enacting safe (i.e. ‘Stop’) and risky (i.e. ‘Go’) decisions, and during the outcome phase following a risky decision (i.e. successful pass) during maternal compared to adult presence. Because certain participants had limited data for crash events, we were unable to test the crash events with the appropriate power. In addition, in some instances, participants did not have enough data for a given condition because they stopped or accelerated at the majority of stoplights (e.g. too few ‘go’ trials under maternal presence). Therefore, the sample size varies slightly by analysis, but never drops below 21.

We conducted psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analyses (O'Reilly, Woolrich, Behrens, Smith & Johansen-Berg, 2012) to examine functional connectivity between the ventral striatum and prefrontal regions associated with cognitive control. Given our a priori predictions, we specified the ventral striatum as the seed region. We structurally defined the striatum using the WFUpickatlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer, Landeau, Pap-athanassiou, Crivello, Etard et al., 2002; Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft & Burdette, 2003). A generalized form of context-dependent PPI was used to run PPI analyses. In particular, the gPPI toolbox in SPM (gPPI; McLaren, Ries, Xu, Fitzgerald, Kastman et al., 2008) was used to (1) extract the deconvolved time-series from the ventral striatum ROI for each participant to create the physiological variables, (2) convolve each trial type with the canonical HRF, creating the psychological regressor, and (3) multiply the time-series from the psychological regressors with the physiological variable to create the PPI interaction terms. The interaction terms identified regions that covaried in a task-dependent manner with the ventral striatum. For the first-level model, one regressor representing the deconvolved BOLD signal was included alongside the psychological and PPI interaction terms for each condition in order to create a gPPI model. Subsequently, at the group level, we conducted random-effects, whole-brain analyses using GLMFlex to examine differences in functional coupling across the Adult and Mother conditions.

In order to correct for multiple comparisons, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation using 3dClustSim in the software package AFNI (Ward, 2000). Results of the simulation indicated a voxel-wise threshold of p < .005 combined with a minimum cluster size of 45 voxels for the whole brain, corresponding to p < .05, Family Wise Error (FWE) corrected, and 44 voxels for our PPI analyses. Because the VS is an anatomically small structure, we did not expect activity in the region to survive these thresholds. Consistent with previous research (Giuliani & Pfeifer, 2015), we used a threshold of p < .005 and 20 voxels for the VS.

Results

Differences in risk-taking behavior during maternal compared to adult presence

Because we had a priori hypotheses of the directionality of our effects such that adolescents would make fewer risky decisions in the presence of their mothers, we ran a one-tailed, paired samples t-test to determine whether differences in rates of risky decisions were significantly different under maternal and adult presence. After removing two outliers, who were over 2.5 SD below or above the mean on risk-taking decisions we found a marginally significant effect (t(20) = -1.58, p = .065) such that adolescents made fewer risky decisions (i.e. ‘go’ decisions) during maternal (M = 56% of trials, SE = .042) compared to adult (M = 60% of trials, SE = .041) presence.

Differences in neural activation during maternal compared to adult presence

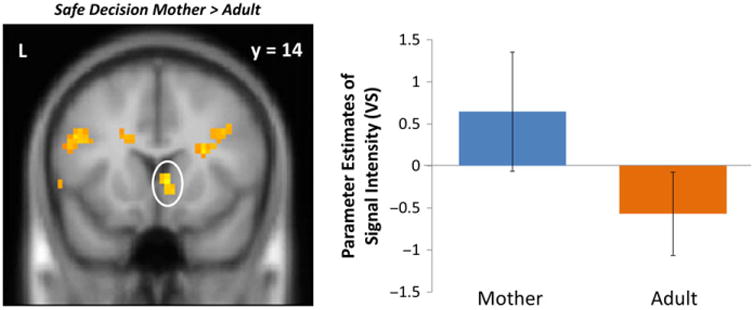

Safe decisions

We observed greater activation in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and fusiform gyrus when mothers were present, compared to another adult (Table 1). The activity in the IFG replicates and extends our previous work (Telzer et al, 2015). When we relaxed the cluster size, we also found greater activation in the VS when adolescents made stop decisions under maternal presence compared to the presence of an adult (k = 18). For descriptive purposes, we extracted parameter estimates of signal intensity from the VS cluster separately for the contrast of Stop decisions when their mother was present and Stop decisions when an adult present. As shown in Figure 2, adolescents exhibit heightened activation in the VS when making stop decisions in the presence of their mother but did not show heightened VS activation in the presence of the adult, suggesting that the intrinsic value of making a safe decision is made more rewarding uniquely by one's parents. No brain regions were more active during adult presence compared to maternal presence.

Table 1. Brain regions which showed significant activation during stop decisions, go decisions, and successful passes.

| Region | BA | x | y | z | t | k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safe Decision Mother > Adult | |||||||

| Ventral Striatum | R | 6 | 14 | −5 | 3.34 | 18* | |

| Fusiform | 37 | R | 42 | −52 | −17 | 3.97 | 147a |

| Cerebellum | R | 24 | −64 | −17 | 3.75 | a | |

| MTG | 37/39 | R | 51 | −52 | 4 | 3.74 | a |

| IOG | 17/18 | L | −48 | −76 | −8 | 3.80 | 47 |

| IFG | 6/8 | L | −45 | 8 | 31 | 4.18 | 175 |

| Cerebellum | L | −24 | −61 | −41 | 3.58 | 65 | |

| Risky Decision Mother > Adult | |||||||

| ACC | 32/34 | L | −9 | 35 | 7 | 4.94 | 168b |

| vlPFC | 46 | L | −36 | 53 | 1 | 3.99 | b |

| dmPFC | 8/9 | R | 9 | 41 | 28 | 4.43 | 146 |

| TPJ | 39 | L | −45 | −49 | 34 | 4.72 | 139c |

| IPL | 7 | L | −36 | −46 | 52 | 5.24 | c |

| Fusiform | 37 | L | −42 | −49 | −20 | 5.48 | 108 |

| mPPC | 31 | R | 6 | −55 | 10 | 3.30 | 51 |

| Thalamus | L | −9 | −10 | 4 | 3.26 | 81d | |

| Putamen | L | −24 | 5 | 13 | 6.41 | d | |

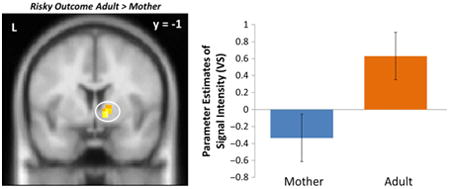

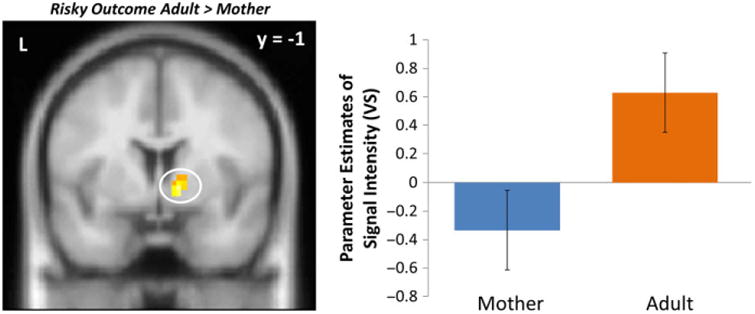

| Risky Outcome Adult > Mother | |||||||

| Ventral Striatum | R | 12 | −1 | −2 | 3.86 | 43* | |

| Superior Frontal Gyrus | L | −24 | 56 | 16 | 3.54 | 69 | |

| TPJ | L | −48 | −52 | 31 | 4.72 | 70 | |

Note: R = right and L = left. x, y, and z refer to MNI coordinates; t = the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima); IFG = inferior frontal gyrus; MTG = middle temporal gyrus; IOG = inferior occipital gyrus; ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; vlPFC = ventrolateral pre-frontal cortex; dmPFC = dorsomedial prefrontal; TPJ = temporopari-etal junction; IPL = inferior parietal lobule; mPPC = medial posterior parietal cortex. Regions that share the same superscript are part of the same cluster.

denotes a priori region with relaxed cluster extent threshold.

Figure 2.

VS activation when adolescents chose to stop in the presence of their mother compared to that of an adult. For descriptive purposes, parameter estimates of signal intensity were extracted from stop > baseline for each condition. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

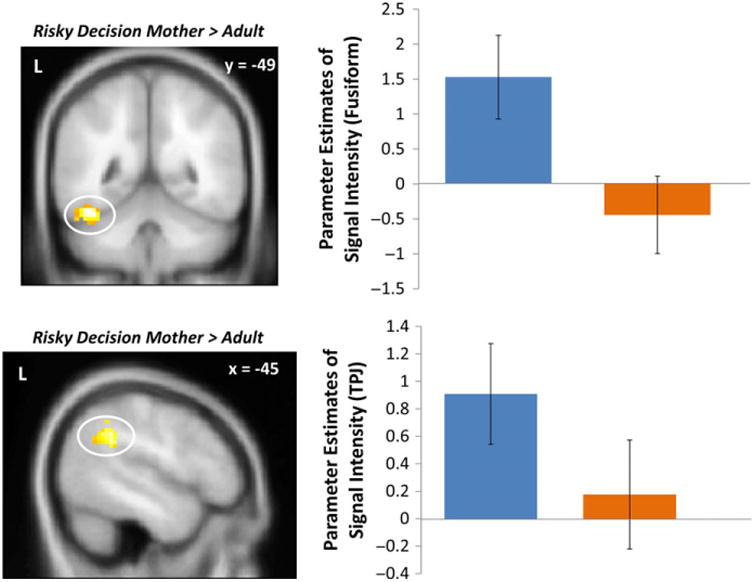

Risky decisions

When making go decisions in the presence of their mother compared to an adult, adolescents displayed greater activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a brain region involved in conflict monitoring. In addition, we found several clusters of increased activation in social brain regions, such that when making a risky decision under maternal presence compared to adult presence, adolescents displayed heightened activation in the TPJ, fusiform gyrus, mPPC, and dmPFC (Figure 3; Table 1). No brain regions were more active during adult presence compared to maternal presence.

Figure 3.

Fusiform and TPJ activation when adolescents chose to go in the presence of their mother compared to that of an adult. For descriptive purposes, parameter estimates of intensity were extracted from go > baseline for each condition. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Risky outcomes

We also examined adolescents' neural responses following a successful pass (i.e. a ‘Go’ decision that did not result in a crash). Following a successful pass, adolescents exhibited greater activation in the VS during adult presence relative to maternal presence (Figure 4, Table 1), replicating prior work (Telzer et al., 2015). We observed greater activation in the superior frontal gyrus and TPJ for adult presence compared to maternal presence.

Figure 4.

VS activity when adolescents successfully passed through an intersection following a risky decision in the presence of an adult compared to their mothers. For descriptive purposes, parameter estimates of intensity were extracted from Risky Outcome > baseline for each condition. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

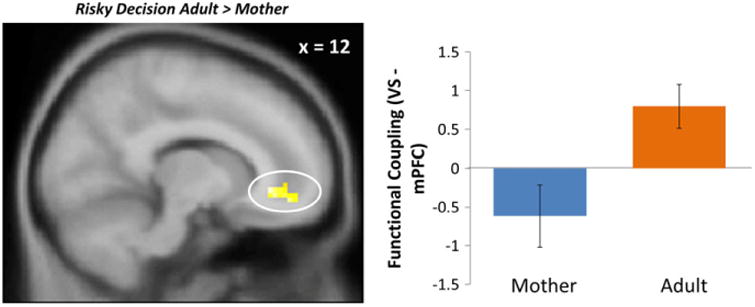

Differences in neural connectivity during maternal compared to adult presence

Next, we conducted PPI analyses using the ventral striatum as the seed region to test for functional connectivity between the VS and the mPFC. We found a significant interaction between the mPFC and VS when adolescents chose to go in the presence of their mothers compared to an adult (Table 2). To further examine this effect, we extracted parameter estimates of signal intensity from the mPFC cluster for each condition separately and plotted these effects. As shown in Figure 5, adolescents displayed positive connectivity (i.e., immature neural pattern; Gee et al., 2014) between the VS and mPFC when making risky decisions in the presence of an adult. However, when adolescents made risky decisions in the presence of their mother, they exhibited more negative coupling between the VS and mPFC, a signature which is considered to be indicative of more mature neural connectivity (Gee et al., 2013). In addition, we found greater coupling between the VS and the fusiform and precuneus when adolescents chose to go in the presence of their mothers compared to another adult. We did not find any significant clusters of functional coupling between the VS and any other regions when adolescents made a stop decision.

Table 2. Brain regions which were functionally coupled with the ventral striatum during go decisions.

| Region | BA | x | y | z | t | k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risky Decision Adult > Mother | |||||||

| mPFC | 11 | R | 12 | 41 | −5 | 3.56 | 62 |

| Risky Decision Mother > Adult | |||||||

| Precuneus | 7 | R | 15 | −46 | 58 | 5.05 | 70 |

| Fusiform | 37 | R | 39 | −52 | −8 | 4.62 | 53 |

Note: R = right and L = left. x, y, and z refer to MNI coordinates; t = the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima); mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex.

Figure 5.

mPFC-VS connectivity when adolescents chose to go in the presence of an adult compared to their mothers. For descriptive purposes, parameter estimates of intensity were extracted from go > baseline for each condition. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Discussion

Adolescence marks a time in which individuals seek more autonomy from their parents and encounter changes across several social contexts (Steinberg, 2001; Larson & Richards, 1991; Dishion & Tipsord, 2011), including ones that possess the capacity for harm or danger (e.g., Cavazos-Rehg, Krauss, Spitznagel, Schootman, Bucholz et al., 2009). These social changes, in conjunction with affective hypersensitivity and poor cognitive control, often leave adolescents at risk for suboptimal health outcomes, most notably stemming from poor decision-making (Steinberg, 2008). In the present study, we examined the specific role of parental presence relative to an unknown adult in providing social scaffolding during risk taking.

We found that adolescents displayed increased ventral striatal activity when choosing to make a safe decision in the presence of their mothers but not in the presence of another adult. However, we note that this VS cluster is relatively small. Based on our a priori hypotheses and replication of prior work, we feel comfortable reporting these results, but also advise readers to interpret these results with caution. In addition, immediately following a successful risky decision, adolescents displayed decreased VS activation under maternal presence relative to adult presence, replicating our prior work which tested the effect of maternal presence, compared to being alone, on adolescent neurocognition during risk taking (Telzer et al., 2015). In the current study, we extend this prior work to show that this VS response is unique to parental presence and does not extend to another adult. One interpretation of these results is that parental presence modulates bottom-up reward sensitivity in a manner that alters the intrinsic value of making a safe decision, thereby increasing the rewarding nature of making safe decisions (Telzer, 2016). Moreover, our results suggest that the presence of an adult does not decrease the pleasure or salience of being risky – this only appears to happen under maternal presence. These results are important for several reasons. First, they help enhance our knowledge of social scaffolding, highlighting that even in adolescence, offspring are still sensitive to parental stimuli. Our results may inform those interested in creating novel intervention programs that target adolescent health risks, especially since extant programs have been largely ineffective (e.g. Stice, Shaw & Marti, 2006; Lapsley & Yeager, 2012; Steinberg, 2015). Our findings suggest that these programs would be more effective if parents played a direct role.

Our findings may also help elucidate the characteristics of developing frontolimbic brain circuits. Although adolescents possess the capacity to independently regulate basic emotions – that is, they show more negative subcortical–cortical functional coupling during basic emotional processing (Gee et al., 2013) – it is less clear whether they still require social scaffolding in more complex socioemotional contexts. We found that adolescents exhibited more positive functional coupling when making risky decisions while another adult was present than when their mothers were present. This immature pattern of neural activation may explain why adolescents tended to make more risky decisions in the presence of a non-parental adult compared to maternal presence. Specifically, it appears that regulatory pre-frontal regions are ineffective at inhibiting the striatal response in the presence of a non-parental adult as evidenced by positive coupling. In contrast, under maternal presence, adolescents did not display this immature neural phenotype, suggesting that maternal presence facilitates more mature and effective neural regulation via top-down inhibitory control from pre-frontal regions. This is notable because previous work has found that adolescents display mature frontolimbic connectivity when regulating basic emotions, regardless of maternal presence, whereas children only display mature connectivity in the presence of maternal stimuli (Gee et al., 2014). Our results suggest that contexts which require scaffolding change across age and development, such that adolescents benefit from maternal scaffolding in developmentally relevant contexts like those which are likely to activate hypersensitive reward systems.

An alternative interpretation of our findings is that the mPFC belongs to a broader reward circuit, helping encode subjective experiences of reward, such that decreases in functional coupling between the VS and mPFC across development are not necessarily indicative of top-down regulation, but instead reflect changes in the nature of how rewards are coded (Crone, van Duijvenvoorde & Peper, 2016). Thus, our findings may suggest that the intrinsic value of risk taking is not as rewarding in the presence of one's mother, compared to another adult, during which the VS and mPFC show strong connectivity. This would imply that maternal presence affects how rewards are coded along this brain circuit. One consideration for future research is determining whether similar patterns of connectivity like the one reported here reflect top-down influences on affective processes or simply the maturation of a larger and broader reward value coding circuit.

Another intriguing component to our findings regard the activation observed in social brain regions. We found increased activation in the TPJ, mPPC, dmPFC, and fusiform gyrus when adolescents chose to enact a risky decision in the presence of their mothers compared to an adult. Presumably, adolescents in our sample were more likely to be concerned with their mother's opinion of their behavior than that of another adult stranger when making a risky decision, an action which teens might assume elicits concern or scorn from their mothers. Because adolescence is an important period for social cognitive processing (Blakemore & Mills, 2014), it is plausible that individuals are more sensitive to their mothers' perspective following a brief instance of misbehavior. Indeed, the TPJ, mPPC, and dmPFC are implicated in perspective taking and mentalizing processes (Blakemore & Mills, 2014), while the fusiform is involved in processing social and emotional salience (Van Bavel, Packer & Cunningham, 2011; McRae, Gross, Weber, Robertson, Sokol-Hessner et al., 2012; Monroe, Griffin, Pinkham, Loughead, Gur et al., 2013), suggesting that adolescents may be processing their risky choices while in the presence of their mothers as a more socially salient event. More broadly, these findings can help address how brain regions involved in social cognitive processes are implicated in decision-making processes and risk-taking contexts.

There are limitations to our study that need to be addressed in addition to interesting considerations for future directions. One limitation and point for consideration in future studies involves the disparity in familiarity between our two conditions. Our teenage participants had a lifetime of experiences and interactions with their mothers, whereas the adult was an unknown stranger. Another limitation is that we did not include a baseline condition in which the adolescent plays the task alone without any other social presence, limiting our ability to fully understand the direction of adult influences on adolescent behavior. Although our findings suggest that results from previous studies (Telzer et al., 2015) appear to be unique to mothers relative to adult strangers, we cannot say whether this would also be the case when compared to fathers, siblings or other prominent, non-familial adults (e.g. teachers, sports coaches, etc.). Future research should examine whether mothers uniquely provide social scaffolding above the effects of other familiar adults. Moreover, future research should examine how relationship quality may modulate the buffering effect of maternal presence. Negative family relationships have been shown to exert detrimental effects on cognitive processes implicated in risk taking such as impulse inhibition (McCormick et al., 2016). Such relationships may fail to provide effective scaffolding for adolescents and may even elicit immature patterns of frontolimbic connectivity.

Researchers studying the effect of social processes on the development of decision-making should also examine broader age groups in future studies in order to determine whether our observed effects are unique to adolescents. Our findings do not indicate whether this pattern of neural activity is a developmental occurrence unique to adolescence or if it manifests itself ubiquitously across the lifespan, making it difficult to make inferences about expanded developmental processes. This is an especially important consideration with regard to our connectivity analyses, as it would allow for insights into the age at which a mature pattern of functional coupling between the limbic system and mPFC is finally assembled, helping contribute to a topic that has recently garnered much attention (Wu, Kujawa, Lu, Fitzgerald, Klumpp et al., 2016; Gabard-Durnam, Gee, Goff, Flannery, Telzer et al., 2016). Longitudinal studies, which follow children into adolescence, will be essential in fully unpacking developmental trajectories of brain maturation. Finally, our sample size was relatively small, which may have precluded our ability to find significant behavioral differences between maternal and adult presence. Previous research has found that both parents and unknown adults reduce adolescent risk taking (Silva et al., 2016; Telzer et al., 2015). Our findings suggest that parents exert a modestly greater effect than unknown adults. Yet, without the power that accompanies a larger sample size, our tests could not fully detect such a difference.

In sum, our results highlight the importance of parents above other adults in guiding their adolescent offspring's behavior in risky scenarios. These findings are the first to suggest that parental presence may be more effective than the presence of other adults to help adaptively scaffold adolescents in vulnerable contexts, highlighting how this occurs at the neural level. Ultimately, our findings speak to the importance of maternal stimuli beyond childhood, underscoring the importance of context in determining whether adolescents benefit from scaffolding.

Research highlights.

Maternal presence buffers risky decision-making in adolescence more than the presence of a non-parental adult.

Reward processing and social cognitive brain systems are engaged when making decisions under maternal presence compared to non-parental adult presence.

Maternal presence elicits relatively more mature functional coupling between the prefrontal cortex and reward processing regions.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank Inge Karosevica and Nicholas Ichien for collecting the data along with the Biomedical Imagining Center at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science. This work was supported by funds from the NSF (SES 1459719) and NIH (R01DA039923) to EHT. Preparation of this manuscript was supported by funding from the Office of Undergraduate Research at the University of Illinois (JFGM).

References

- Blakemore SJ, Mills KL. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology. 2014;65:187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ. Beyond simple models of self-control to circuit-based accounts of adolescent behavior. Annual Review of Psychology. 2015;66:295–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Schootman M, Bucholz KK, et al. Age of sexual debut among US adolescents. Contraception. 2009;80(2):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chein J, Albert D, O'Brien L, Uckert K, Steinberg L. Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain's reward circuitry. Developmental Science. 2011;14(2):F1–F10. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, Duijvenvoorde ACK, Peper JS. Annual Research Review: Neural contributions to risk-taking in adolescence – developmental changes and individual differences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2016;57(3):353–368. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE. Adolescent brain development: a period of vulnerabilities and opportunities Keynote address. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021(1):1–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Tipsord JM. Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:189–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabard-Durnam LJ, Gee DG, Goff B, Flannery J, Telzer E, et al. Stimulus-elicited connectivity influences resting-state connectivity years later in human development: a prospective study. Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36(17):4771–4784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0598-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, Humphreys KL, Flannery J, Goff B, Telzer EH, et al. A developmental shift from positive to negative connectivity in human amygdala-prefrontal circuitry. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33(10):4584–4593. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3446-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, Gabard-Durman L, Telzer EH, Humphreys KL, Goff B, et al. Maternal buffering of human amygdala-prefrontal circuitry during childhood but not adolescence. Psychological Science. 2014;25:2067–2078. doi: 10.1177/0956797614550878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani NR, Pfeifer JH. Age-related changes in reappraisal of appetitive cravings during adolescence. NeuroImage. 2015;108:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser TU, Iannaccone R, Walitza S, Brandeis D, Brem S. Cognitive flexibility in adolescence: neural and behavioral mechanisms of reward prediction error processing in adaptive decision making during development. NeuroImage. 2015;104:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapsley D, Yeager D. Moral-character education. In: Weiner IB, editor. Handbook of psychology. Vol. 7. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2012. pp. 117–146. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Richards MH. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: changing developmental contexts. Child Development. 1991;62(2):284–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick EM, Qu Y, Telzer EH. Adolescent neurodevelopment of cognitive control and risk-taking in negative family contexts. NeuroImage. 2016;124:989–996. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren DG, Ries ML, Xu G, Fitzgerald ME, Kastman EK, et al. A method for improved sensitivity and flexibility of psychophysiological interactions in event-related fMRI experiments. Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping 2008 [Google Scholar]

- McRae K, Gross JJ, Weber J, Robertson ER, Sokol-Hessner P, et al. The development of emotion regulation: an fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal in children, adolescents and young adults. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012;7(1):11–22. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. NeuroImage. 2003;19(3):1233–1239. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe JF, Griffin M, Pinkham A, Loughead J, Gur RC, et al. The fusiform response to faces: explicit versus implicit processing of emotion. Human Brain Mapping. 2013;34(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly JX, Woolrich MW, Behrens TE, Smith SM, Johansen-Berg H. Tools of the trade: psychophysiological interactions and functional connectivity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012;7(5):604–609. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Galvan A, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, Telzer EH. Longitudinal changes in prefrontal cortex activation underlie declines in adolescent risk taking. Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35(32):11308–11314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1553-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva K, Chein J, Steinberg L. Adolescents in peer groups make more prudent decisions when a slightly older adult is present. Psychological Science. 2016;27(3):322–330. doi: 10.1177/0956797615620379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Jones RM, Casey BJ. A time of change: behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain and Cognition. 2010;72(1):124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24(4):417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Rewards, aversions and affect in adolescence: emerging convergences across laboratory animal and human data. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;1(4):390–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review. 2008;28(1):78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52(3):216–224. doi: 10.1002/dev.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. How to improve the health of American adolescents. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10(6):711–715. doi: 10.1177/1745691615598510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: the skinny on interventions that work. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(5):667–691. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH. Dopaminergic reward sensitivity can promote adolescent health: a new perspective on the mechanism of ventral striatum activation. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2016;17:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, Galvan A. Meaningful family relationships: neurocognitive buffers of adolescent risk taking. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;25(3):374–387. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Ichien NT, Qu Y. Mothers know best: redirecting adolescent reward sensitivity toward safe behavior during risk taking. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2015;10:1383–1391. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai KM, Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ. Continuity and discontinuity in perceptions of family relationships from adolescence to young adulthood. Child Development. 2013;84(2):471–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage. 2002;15(1):273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel JJ, Packer DJ, Cunningham WA. Modulation of the fusiform face area following minimal exposure to motivationally relevant faces: evidence of in-group enhancement (not out-group disregard) Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23(11):3343–3354. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward BD. Simultaneous inference for fMRI data. AFNI 3dDeconvolve Documentation, Medical College of Wisconsin; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Kujawa A, Lu LH, Fitzgerald DA, Klumpp H, et al. Age-related changes in amygdala-frontal connectivity during emotional face processing from childhood into young adulthood. Human Brain Mapping. 2016;37:1684–1695. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]