Abstract

Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) is a rare hereditary autosomal dominant cancer disorder. Germ-line mutations in TP53 are responsible for most cases of LFS. p53 is also the most commonly mutated gene in human cancers. Because inhibition of mutant p53 is considered a promising therapeutic strategy to treat these diseases, LFS provides a perfect genetic model to study p53 mutation-associated malignancies as well as screen potential compounds targeting oncogenic p53. In this review, we will briefly summarize the biology of LFS and the current understanding of oncogenic functions of mutant p53 in cancer development. We will discuss the strengths and limitations of current LFS disease models and touch on existing compounds targeting oncogenic p53 and in vitro clinical trials to develop new ones. Finally, we discuss how recently developed methodologies can be integrated into the LFS iPSC platform to develop precision cancer therapy.

Keywords: Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, Mutant p53 Gain of Function, Disease Model, Pluripotent Stem Cells, Drug Screening and Development, In Vitro Clinical Trial

Discovery of Li-Fraumeni syndrome and identification of p53 as critical gene for tumorigenesis

Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) (OMIM #151623) is a rare familial autosomal dominant cancer syndrome characterized by early onset of multiple tumors, particularly soft-tissue sarcomas, osteosarcomas, breast cancers, brain tumors, adrenocortical carcinomas and leukemia. LFS was first described in 1969 by Li and Fraumeni [1, 2] (Figure 1). In reviewing 280 medical charts and 418 death certificates of 648 childhood rhabdomyosarcoma patients in the United States from 1960 to 1964, they identified four families in whom a second child had developed a soft tissue sarcoma. These 4 families also had striking histories of breast cancer and other neoplasms, suggesting a previously undescribed familial cancer syndrome (https://www.omim.org/entry/151623).

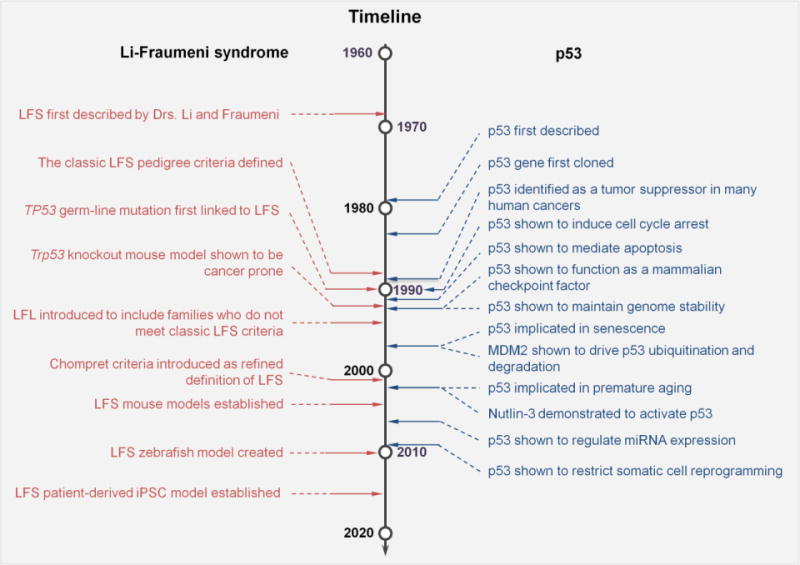

Figure 1. Milestones of LFS and p53 research.

Left column timeline shows important research developments in LFS, including discovery of the disease, identifying underling genetic cause and establishment of the disease model. The right column timeline lists out the comparable key findings during 38 years of research on p53.

The classic LFS pedigree was defined in the proband as a patient with sarcoma diagnosed before age 45, plus a first-degree relative with any cancer before the age of 45 years and another first- or second-degree relative with any cancer before the age of 45 years or a sarcoma at any age. This definition was based on 24 kindreds with the syndrome of sarcoma, breast carcinoma and other neoplasms in young patients [3]. The defined criteria for this syndrome gradually evolved to include not only classic LFS, but also Li-Fraumeni-like syndrome (LFL), which shares features of LFS but does not conform to the strict definition [4].

While the six core cancers mentioned above account for the majority of LFS associated tumors, the remaining cancers include diverse carcinomas of the lung, stomach, ovary, and colon/rectum, as well as lymphoma, melanoma and other neoplasms [5]. Half of patients with LFS develop at least one LFS-associated cancer before age 30, compared to a 1% incidence of cancer before age 30 in the general population [6]. The lifetime risk of cancer in LFS is estimated to be 73% for males and almost 100 % for females, with the increased risk of breast cancer accounting for the difference [7, 8].

LFS patients are also at a remarkably increased risk for developing a second malignancy [9, 10]. A study of 200 LFS patients from 24 kindreds showed that 57% of patients developed a second malignancy within 30 years after diagnosis of the first cancer [10]. LFS patients also are at increased risk of developing treatment-related secondary malignancies. Several case reports suggested that ionizing radiation-induced cancers are more common in LFS patients [11–13], and research studies also support this relationship [14, 15]. Therefore, radiation therapy is generally avoided in the management of these patients if possible. A stringent surveillance strategy is one of the key components of LFS patient management. A prospective clinical trial aimed at improving cancer screening for LFS patients showed that a surveillance strategy including whole body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other biochemical tests was able to detect tumors earlier, which is associated with improved long-term survival [16].

In 1990, Malkin et al. used a candidate gene approach to first link a TP53 germ-line mutation to LFS [17]. Srivastava et al. later analyzed TP53 mutations in a LFS family, identifying the same point mutation in codon 245 of the TP53 gene in different generations of this pedigree [18]. Together with the previous observations that p53 is also inactivated in the sporadic (non-familial) forms of cancers, these studies suggested the loss of p53 as a rate-limiting step for tumorigenesis [17], and implied that inherited TP53 mutations could be responsible for the increased susceptibility to cancer.

The initial detection of a TP53 heterozygous point mutation was only carried out in five LFS families [17]. Numerous subsequent studies have shown that approximately 70% of LFS families harbor detectable germ-line TP53 mutations [4, 19–22]. These mutations are also highly associated with a significant increase in DNA copy number variations (CNVs) [23]. For those patients without detectable TP53 mutations, a complete heterozygous germline deletion of TP53 was reported [24], indicating that rearrangements affecting TP53 occur rarely, but should be considered in LFS families. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (https://www.nccn.org/), TP53 genetic testing is recommended for individuals from a family with a known TP53 mutation, or individuals who meet either the classic LFS criteria, the Chompret criteria [25], or who were diagnosed with breast cancer before age 31. To date, TP53 germ-line variants from more than 700 LFS pedigrees have been reported and integrated into the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) TP53 Database (http://p53.iarc.fr/), providing updated resources of hereditary TP53 variants, such as the distribution of the mutations over the TP53 codon and the influence of different types of mutations on the tumor spectrum [26].

Biological Functions of p53: ever-growing complexity

As a central regulator within an extremely complex biological network, p53 plays a much broader role in many normal cellular and developmental processes besides its well-known tumor suppressor function. The most extensively studied mechanism by which wild-type (WT) p53 functions is as a transcription factor, regulating expression of a set of target genes that are involved in cell-cycle arrest, senescence, apoptosis and DNA damage repair [27–29]. Beyond these classic functions, p53 also plays roles in regulating glucose metabolism [30, 31], antioxidant activities [31–33], autophagy [34, 35], motility and invasion [36], angiogenesis [37], bone remodeling [38, 39], stem cell self-renewal [40, 41], differentiation [42–49], and somatic cell reprogramming [50–52]. Most of these biological processes regulated by p53 have also been proved to contribute to its tumor suppressive effect [29], although there is emerging evidence of a “dark side” of p53 in which WT function prevents cell death or even promotes cancer development and progression [53–55].

Although much still needs to be understood about this ever-growing p53-associated network, it is clear that restoration of functional WT p53 leads to tumor growth suppression [56–58]. Therapeutic manipulation of p53 is an ongoing hot research field, and more than 100 related clinical trials have been conducted [59]. Translation of our current knowledge of p53 into the clinic has been challenging and is often complicated by the interplay between WT and mutant p53, mutant p53 gain-of-function, inconsistent findings from different study systems, and the versatility of p53 under distinct microenvironments. Still, novel and creative approaches to treat p53-associated diseases are in high demand.

Mutant p53 gain-of-function: more than just a loss

TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in human cancers [60, 61]. Deletion or truncation mutations in p53 abrogate its normal function by attenuating p53-responsive cellular activities; when both alleles become mutated, the anticancer protection of p53 will be shut down. Although loss of normal p53 function is one of the common features in cancer, p53 does not fully follow the classic Knudson’s “two-hit” theory during carcinogenesis or cancer progression [62]. It is not simply the loss of WT p53 that drives cells to cancer. The majority of the p53 mutations found in tumors are missense mutations, resulting in production of full-length protein with only one amino acid change [44, 63]. Many of these mutant p53 exhibit a dominant-negative effect over WT p53, mostly by forming mixed tetramers with diminished DNA binding and transactivation activity [64]. In this way, mutation of only one copy of p53 may lead to many of the downstream effects that would otherwise require loss of both copies.

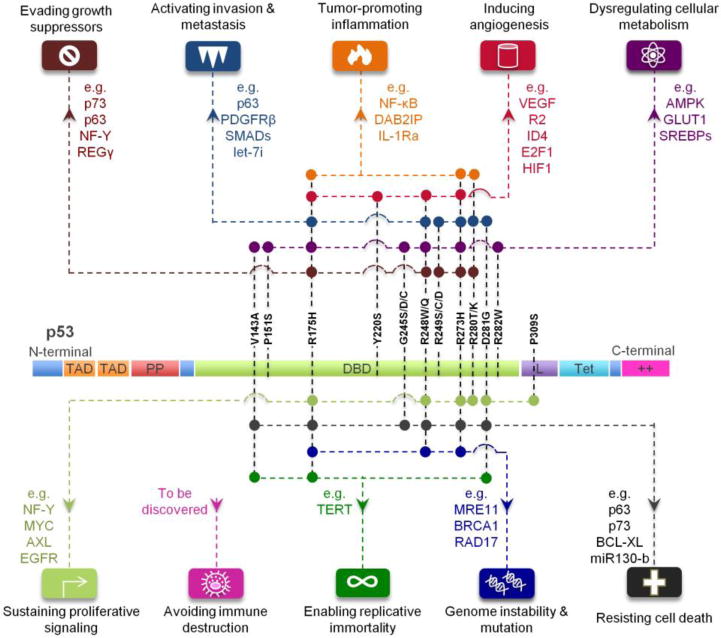

Probably the most striking fact about the p53 mutation landscape in cancer is the high prevalence of missense substitutions at certain spots, mainly at the DNA binding domain (DBD) [63] (Figure 2). These ‘hotspot’ mutations indicate selective advantages during cancer development and progression. Indeed, many hotspot mutations arm the mutant p53 with new weapons to promote cancer. Such activities, known as mutant p53 gain-of-function, are involved in regulation of various cancer hallmarks (Figure 3), including genomic instability [65–69], anti-apoptotic activities [70–79], replicative mortality [69, 80], invasion and metastasis [63, 64, 66, 67, 79, 81–91], angiogenesis [92–95], dysregulated metabolism [96–99], and tumor-related inflammation [100–103]. Mutant p53 gain-of-function can drive cancer through several potential mechanisms [104, 105]: (i) binding to structure-specific DNA to subsequently exert transcriptional regulation; (ii) interacting with transcription factors or cofactors to enhance or decease transcription of their targeted genes; (iii) associating with chromatin or the chromatin regulatory complex; and (iv) directly interacting with and influencing other proteins and their functions.

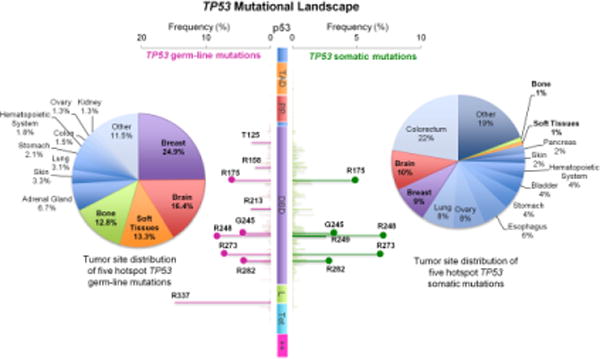

Figure 2. Mutational landscape of TP53 germline and somatic mutations in human cancer.

TP53 missense mutation data is obtained from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) TP53 database (http://p53.iarc.fr/). Distributions of p53 mutations are plotted over the function of amino acid position, where left side indicating germline mutations and right side indicating somatic mutations. Horizontal axis shows the frequency of any mutation at indicated residues. Vertical axis is the schematic of the p53 protein starting with N-terminal at the top. p53 protein domain contains transcriptional activation domain I and II (TAD 1, 20–40; TAD II, 40–60), the proline domain (PP, 60–90), the sequence-specific core DNA-binding domain (DNA-binding core, residues 100–300), the linker region (L, 301–324), the tetramerization domain (Tet, 325–356), and the lysine-rich basic C-terminal domain (++, 363–393). Most common mutations on “hot spot” are indicated as bold line; R175, G245, R248, R273, R282 residue are the five common hot spots in both germline and somatic mutations (indicated as lollipop). Pie charts illustrate the tumor site distribution of five hotspot TP53 mutations (left, germline; right, somatic). Malignancies located at breast, brain, soft tissues and bone are most commonly seeing over the five hotspot germline mutations; malignancies from these tumor sites are also distributed in the same five hotspot of TP53 somatic mutations (indicated in bold).

Figure 3. Mutant p53 gain-of-function driver cancer through cancer hallmarks.

Different mutations on p53 protein (structure details describe in the previous figure) arm p53 with new weapons (downstream targets indicted in the figure) to drive cancer development and progression. Each color-coded node indicates gain-of-function of specific mutation of TP53, which further drives cancer through various cancer hallmarks.

Several excellent reviews [64, 104–113] have addressed p53 gain-of-function from various aspects. Here, we will highlight some of the most recent discoveries on mutant p53 gain-of-function and address their therapeutic potential in cancer treatment.

Regulating imprinted genes

Aberrant imprinting or dysregulation of imprinted genes are associated with developmental disorders and an increased risk of cancer [114–116]. Alterations in the expression of genes in the H19-IGF2 imprint locus have been described in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) [117] and Russell-Silver syndrome (RSS) [118], which are associated with risk for Wilms tumor, hepatoblastoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Bidirectional links between WT p53 and imprinted genes in the H19-IGF2 locus have been demonstrated in several studies [119–121]. Loss of imprinting of IGF2 accelerates tumor formation by inactivating WT p53 [119]. Maternally imprinted H19, which encodes a long noncoding RNA, has been shown to be negatively regulated by p53 [120]. In 2015, this link was extended to the mutant p53. A study by Lee et al. revealed that numerous p53 mutants exhibit gain of function and can inhibit H19 expression [122]. Using LFS patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to model osteosarcoma, this study found that the p53 (G245D) mutant represses H19 expression during osteoblastic differentiation. Moreover, many hotspot p53 mutants including R175H, G245S, R248W, and R280K also showed strong inhibition of H19 expression compared to WT p53, indicating that mutant p53 gain-of-function in regulating imprinted gene expression is a general mechanism in LFS-associated osteosarcoma across distinct p53 mutations.

Driving cancer through interplay with chromatin

One of the features of gain-of-function mutant p53 is the ability to associate with chromatin and other transcriptional factors to globally influence the gene expression profile [77, 96, 101, 123, 124]. Recently, it was shown that multiple mutant p53 forms bind to the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex [95]. This interaction with the SWI/SNF complex mediates up to 40% of the mutant p53 regulated genes, including angiogenesis promoting gene VEGFR2, further suggesting that repressing the SWI/SNF complex or its downstream targets (e.g. by anti-VEGF) may help reverse the changes caused by mutant p53-mediated in cancer. A proteome-wide analysis found that the p53 (R273H) mutant is tightly associated with chromatin and can modulate the protein levels of PARP, PCNA, and MCM4 in a transcription-independent manner [125]. Inhibition of PARP activity showed efficacy in treating these mutant p53 expressing cancer cells. Another mutant p53 gain of function causes mutant p53 to interact specifically with transcription factor ETS2 and leads to upregulation of chromatin regulatory genes, including MLL1, MLL2 and KAT6A, resulting in a global increase of histone modifications (methylation and acetylation) and tumor progression [126]. This suggests the possibility of therapeutic inhibition of the MLL1 methyltransferase complex to decrease cancer cell proliferation.

Driving oncogene expression by repressing transcription factors

Mutant p53 can exert its pro-oncogenic properties by physically interacting with the p53 family members, p63 and p73, and altering their transcriptional activity [78, 81, 127, 128]. Mutant p53 promotes pancreatic cancer invasion and metastasis by upregulating the cancer driver PDGFRG [129]. p53 mutants at the hotspot sites R175H and R273H were shown to bind to the p73/NF-Y complex. This interaction impairs the repressive transcriptional regulation of p73 on PDGFRB at the PDGFRB promoter region. The study also showed that inhibition of PDGFRG using RNAi or small molecules is effective in attenuating metastasis in vivo, suggesting a possible target in controlling metastasis in p53 mutant pancreatic cancer.

Current LFS disease models

Engineered mouse models

Engineered mouse models have been used extensively for mammalian in vivo and in vitro studies of LFS. In 1992, in order to investigate the role of the p53 gene in mammalian development and tumorigenesis, a null mutation was introduced into the gene by homologous recombination in murine embryonic stem cells [130]. Mice homologous for the null allele (p53−/−) appear developmentally normal but are highly susceptible to early onset of a variety of neoplasms. Subsequent homozygous knockout mice with different deletions of the p53 allele showed similar tumorigenic phenotypes [131, 132].

However, a more reasonable genetic model for LFS with heterozygous mutations in p53 is needed, because LFS patients are invariably heterozygous rather than homozygous for mutant p53. With this in mind, heterozygous p53-null mice (p53+/−) were generated. Nearly 50% of them developed tumors by 18 months of age, although with a comparative cancer onset delay compared with homologous mice. This was roughly similar to the 50% cancer incidence prior to age 30 in affected LFS individuals, given that C57BL/6 mice have an average lifespan of 30 to 36 months [133]. The similarities between p53+/− mice and LFS patients are even more striking with respect to their tumor spectrum. p53+/− mice develop osteosarcomas and soft tissue sarcomas, as seen with high frequency in LFS families, while homozygous mice predominantly develop malignant lymphomas [134].

Missense mutations are the most common mutations in affected LFS individuals apart from null mutations. Mouse models of these mutations garnered significant attention in the p53 research community. In 2000, the first heterozygous mouse containing an R to H substitution at p53 amino acid 172 was generated, which corresponds to the R175H hot spot mutation in human cancers and the germ-line mutation in LFS kindreds [135]. Although this model contained an unexpected deletion of a G nucleotide at a splice junction that attenuated levels of mutant p53 to near WT levels, mice heterozygous for the mutant allele differed from p53+/− mice, as the osteosarcomas and carcinomas developed in these missense mutant mice frequently metastasized (69% and 40%, respectively). This indicated, for the first time, that a p53 missense mutation could confer a gain of function in vivo, even when expressed at relatively low levels.

Later in 2004, two groups independently reported knock-in mouse models of LFS expressing the p53 mutation allele R172H and R270H (p53M/−), equivalent to the codons 175 and 273 in humans [136, 137] (Table 1). Both studies demonstrated that p53M/− mice developed a broader tumor spectrum with a more invasive and metastatic phenotype compared to p53+/− mice, although no change in survival was observed. This broad spectrum of tumors included a variety of carcinomas, bone sarcomas, leukemias, and even a glioblastoma multiforme (GBM, the most common brain tumor in LFS), indicating p53M/− mice better recapitulate the human LFS familial syndrome than p53+/− mice. Interestingly, p53M/− or p53+/− mice did not develop breast cancer, one of the most common tumors in LFS patients but increased the incidence to develop hematological malignancies (e.g., lymphomas) [136, 137], implying either possibility of species differences or a susceptible genetic background required for the veracity of these mice models.

Table 1.

Current LFS disease models

| Model | p53 mutation | Mutant p53 function | LOH | Tumor types | Metastasis | Model system | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | I166T | Dominant negative | Yes | Broad spectrum | N.A. | In vivo | [141] |

| Heterozygous mouse | R172H and R270H | Gain of function | Yes | Broad spectrum | Yes | In vivo | [136, 137] |

| HUPKI mouse | R175H, R245S, R248Q, R248W and R273H | Gain of function | N.A. | Broad spectrum | N.A. | In vivo | [65, 139, 140] |

| Patient derived iPSCs | G245D | Gain of function | N.A. | Osteosarcoma | N.A. | In vitro | [122] |

N.A., not available

Similarly, HUPKI (humanized p53 knock-in) mouse models [138] were constructed by targeting the mutant human TP53 DNA sequence into murine embryonic stem cells (Table 1). HUPKI models were generated for the human mutations R175H, G245S, R248W, R248Q and R273H [65, 139, 140]. All these knock-in mice except the G245S model showed a broader tumor spectrum than p53 null mice, providing strong support for the gain-of-function hypothesis of various missense p53 mutants in driving and enhancing spontaneous tumorigenesis.

Zebrafish models

Another model of LFS was created in zebrafish (Table 1), a powerful vertebrate system that is accessible to both large-scale screens and in vivo manipulation for cancer studies [141]. A forward genetic screen was performed using a specific ionizing radiation (IR)-induced phenotype in zebrafish embryos, leading to the identification of the p53 I166T mutations. This mutation was shown to give rise to tumors, predominately sarcomas, with 100% penetrance in adult fish. As in humans with LFS, heterozygous p53I166T follow Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis, in which the tumors displayed loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the p53 locus. Additionally, the data demonstrated that the p53 regulatory pathway, including Mdm2, is evolutionarily conserved in zebrafish. This work demonstrated the potential of zebrafish models to discover novel genes and therapeutic compounds that modulate the evolutionarily conserved LFS pathway.

Primary cell line system

Researchers have also gained insight into LFS through direct investigation of patient primary cells. A comparison of soft tissue sarcomas, including fibrosarcomas, from affected LFS patients with fibroblasts derived from skin biopsies from the same patients demonstrated chromosomal anomalies, resistance to senescence, and spontaneous immortalization in the LFS fibroblasts compared with control cultures [142, 143]. Immortalization of these cells appeared to be associated with loss of the WT p53 allele, p16INK4 expression and telomere elongation [144–146]. Loss of p53 during this immortalization has been shown to cause a decrease in TSP-1 expression, a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis, and switch the LFS fibroblasts to a pro-angiogenic phenotype [147, 148]. In addition, normal breast epithelial cells obtained from a patient with LFS (with a mutation at codon 133 of the p53 gene) spontaneously immortalized during in vitro culture, while breast stromal fibroblasts from this same patient did not [149]. The immortalization of normal cells from LFS patients strongly indicates that transformation is characteristic of the LFS genetic background.

Patient-derived iPSCs

The motivation for use of patient-derived iPSCs stems from limitations inherent to other systems. Animal models do not fully represent human LFS disease features, while primary cells from affected patients are limited to a few cell types [150, 151]. In order to access a wider spectrum of cell types, iPSCs were generated from patient fibroblasts obtained from a LFS family with a heterozygous p53(G245D) hot spot mutation and differentiated into targeted lineages [122] (Table 1). Despite their defective p53 function, LFS iPSCs-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) maintained normal MSC characteristics and could be differentiated into osteoblasts. Interestingly, once turned into osteoblasts, the cells expressed an osteosarcoma signature by genome-wide transcriptome analysis. LFS osteoblasts recapitulated the differentiation defects and oncogenic properties of osteosarcoma. Part of this phenotype was shown to be mediated by repression of the imprinted gene H19 by mutant p53 gain-of-function. Furthermore, LFS osteoblasts and tumors in this model system showed a only negligible number of the cytogenetic rearrangements commonly found osteosarcoma, indicating the existence of a relatively intact genome in this model system and the feasibility of studying early cancer progression prior to accumulation of broad genome alterations. These data show that the LFS iPSC disease model successfully transforms clinical samples into cell line models. As techniques for directed differentiation improve, this technique may be applied to study many more cancer types found in affected LFS families.

Prospective LFS disease models

Existing LFS models have various limitations. Mouse and zebrafish models have species differences with human LFS patients. Primary cells from LFS families are limited to only a few cell types and challenging to obtain and maintain. Only a limited number of all adult tissue types are currently accessible through directed differentiation of LFS iPSCs. The developing methods of patient-derived tumor xenograft (PDTX) and conditional reprogramming (CR) may provide alternative approaches to compensate for limitations in current models.

PDTXs are obtained by directly implanting freshly resected patient tumor pieces subcutaneously or orthotopically into immuno-compromised mice [152]. Numerous tumor-specific PDTX models have been established. Importantly, they are biologically stable when passaged in mice in terms of global gene-expression patterns, mutational status, metastatic potential, drug responsiveness and tumor architecture [153]. They often preserve the molecular and cellular basis of tumor heterogeneity and have been shown in certain cases to predict therapeutic responses [154]. These features suggest that PDTX models may reliably predict clinical activity of novel compounds in cancer patients.

CR is a cell culture technique used to rapidly and efficiently establish patient-derived cell cultures from both human normal and tumor cells [155], which is accomplished by co-culturing them with irradiated mouse fibroblast feeder cells in the presence of a Rho kinase inhibitor (Y-27632). In CR culture conditions, cells are rapidly reprogrammed to cells with the characteristics of adult stem cells. When transferred into conditions that mimic in vivo environments, they reverse back to differentiated states, and organize into structures similar to the tissue from which they were derived. Comparing to immortalized cells, CR cells maintain the phenotypic and genotypic features of the primary tumors, thus providing a faithful preclinical model. Moreover, taking advantage of its rapid and efficient expansion of cell cultures, CR can be applied to drug screen quickly enough to provide information for clinical use. Meanwhile, this large amount of cells can be used in PDTX and organoid cultures.

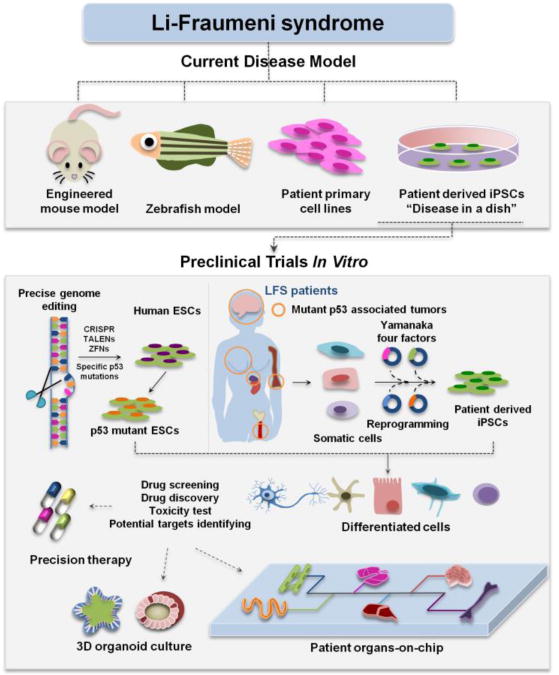

In conclusion, the combination of the techniques mentioned above provides a brighter vision of the disease modeling (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The application of LFS iPSC model to drug development for LFS and p53 mutation-associated tumors.

LFS iPSC model overcomes the limitations of current LFS disease models like mouse model, zebrafish model and primary cell lines, and holds potentials in modeling LFS associated cancers and facilitating clinical trials in a dish. Precise genome editing techniques make it possible to expand the bank of PSCs with different p53 mutations, which provides valuable resource for precision cancer medicine. Integration of 3D organoid and organs-on-chip with LFS iPSC disease model offers exciting opportunities for testing existing both WT and mutant p53-associated pathway related drugs and discovering new therapeutic compounds.

Translating LFS iPSC models into clinical therapies

In vitro Clinical Trials

Animal models are conventionally used to test efficacy and toxicity of preclinical compounds. Although these surrogate models are valued as gatekeeper in clinical trials, they often yield disappointing results due to fundamental differences between species [156, 157]. Failure to translate results from animal models into clinical trials led to suggestions that therapies also be tested for efficacy on specimens collected from patients during pre-clinical trials. This concept of in vitro clinical trials as advanced by the FDA also emphasizes utilizing new scientific methodology that enables testing treatment strategies on living human tissues [158]. The availability of iPSC technology has augmented the potential of clinical trials in a dish [157]. Increasingly refined differentiation protocols have enabled the generation of large quantities of differentiated cells of various types from patient-derived iPSCs. An unlimited supply of otherwise inaccessible disease-relevant cells should permit in vitro drug screening, toxicity testing and drug response prediction.

Patient-derived iPSCs have been used to model various diseases, including long QT syndrome (LQTS) [159, 160], alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency [161, 162], familial dysautonomia (FD) [163, 164] Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA) [165–167], familial Alzheimer’s disease [168] and RASopathy disorders [169, 170], to name a few. Successful disease modeling not only sheds light on disease mechanisms but also leads to the development of in vitro assays – readouts of disease-associated phenotype – that facilitate high-throughput drug screening. AAT deficiency patient iPSC-derived hepatocyte-like cells have been used to conduct large scale screening of clinically available compounds for the purpose of discovering potential treatments [171]. High-throughput screening to identify small-molecule compounds to rescue IKBKAP expression in FD iPSC-derived neural crest cells revealed the potential of an α2-adrenergic receptor (α2-AR) antagonist in FD treatment [163]. Another recent study also utilized iPSC-derived hematopoietic progenitors to perform a non-biased drug screening for DBA, which identified autophagy as a therapeutic pathway in this rare blood disorder. iPSC-based drug screening has also been applied to diseases other than genetic disorders, such as infectious diseases [167]. iPSC-derived hepatocytes have been used to screen drugs for treating chronic infectious disease, such as hepatitis B and liver-stage malaria [172, 173]. High-throughput drug screenings have also been carried out to identify potential antiviral drugs using iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and neurons from patient with viral cardiomyopathy or Zika virus infection [174, 175].

One of the critical steps for developing clinical drugs is to test toxicity, which often leads to failure and/or withdrawal of preclinical drugs [176]. Increasing attention is being paid to models for predicting drug-induced toxicity down to the single-patient level. Human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) are proving useful in predicting a drug-induced prolonged action potential (also referred to as long QT), which places patients at high risk of life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias [177]. A recent study reported the use of iPSC-CMs in predicting doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in cancer patients [178], suggesting the benefits of generating patient iPSCs and examining toxicity prior to initiating chemotherapy.

LFS iPSC model: new opportunities for screening compounds

Given its role as a tumor suppressor and high rate of mutation in cancer, p53 poses an attractive target for cancer therapy. Many human tumors require loss of WT p53 or gain-of-function of mutant p53 to progress to a fully malignant phenotype. Thus, significant efforts have been devoted to p53-based drug development targeting both wide type and mutant forms of p53. These strategies include: (i) WT p53 activation, (ii) mutant p53 restoration, (iii) mutant p53 elimination, and (iv) p53 family inhibition, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Compounds targeting WT and mutant p53

| Target | Compound | p53 | Mechanism | Testing Stage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT p53 Activation | RITA | WT | Inhibition of p53 binding | Preclinical | [181] |

| Nutlin-3 | WT | Inhibition of p53-MDM2 interaction | Phase I | [182] | |

| MI-219 | WT | Inhibition of p53-MDM2 interaction | Preclinical | [183] | |

| Mutant p53 Restoration | NSC319726 | R175H | Restore WT structure and its transactivational function | Preclinical | [189] |

| PhiKan083 | Y220C | Raise the melting temperature of mutant p53 and slow down its denaturation rate | Preclinical | [190] | |

| WR-1065 | V272M | Restore the WT conformation of the temperature-sensitive p53 mutant V272M | Phase I | [191] | |

| Mutant p53 Elimination | Hsp90 inhibitors: 17-AAG | R175H, L194F, R273H, R280K, | Destroy the complex mutant p53/HSP90 to release mutant p53 for its degradation | Phase I/II/III | [193] |

| HDAC inhibitors: SAHA | R175H, R280K, V247F/P223L | Inhibit HDAC6 and disrupt the HDAC6/Hsp90/mutant p53 complex | Phase I/II | [194] | |

| HMG-CoA Reductase inhibitor: Statins | R156P, R175G, Y220C | Inhibit Mevalonate pathway and interfere HSP40/DNAJA1/mutant p53 complex | Phase I/II/III | [195] | |

| p53 family inhibition | RETRA | R273H, R248W G266E R280K | Increase the p73 levels and release p73 from mutant p53/p73 complex | Preclinical | [238] |

WT p53 remains at relatively low intracellular levels predominantly due to ubiquitination by the E3 ligase MDM2 for rapid degradation [179]. In many cancers, the MDM2 proteins are dysregulated and exert an oncogenic function mainly by inhibiting the p53 tumor suppressor [180]. As a result, considerable efforts have been made to develop compounds that interfere with the p53-MDM2 interaction, leading to the discovery of Nutlin-3, RITA and MI-219 [181–183]. In addition, a new class of stapled peptides, designed to contain a hydrophobic binding interface that mimics the bound α-helical conformation of p53, have been shown to effectively block the p53-MDM2 interactions [184–186]. Besides regulating WT p53, MDM2 can also regulate the degradation of mutant p53, and loss of MDM2 promotes tumor development in mutant p53 mice [187]. This implies that drugs aimed at activating WT p53 by inhibiting MDM2 will also stabilize mutant p53 with adverse consequences.

Mutant p53 is also an attractive druggable target, since mutant p53 protein is expressed at high levels in various tumor types but generally not found in normal cells [188]. To accomplish this, two strategies have been attempted: restoration of WT p53 transcriptional activity; and depletion of mutant p53. The feasibility of restoration of WT activity in mutant protein stems from observations that loss of WT function introduced by some destabilizing mutations can be rescued by additional point mutations that stabilize the conformation of the p53 protein [152]. As a result, a variety of compounds that might restore WT p53 function have been characterized, including NSC319726 [189], PhiKan083 [190], and WR-1065 [191].

Depletion of oncogenic mutant p53 turns out to be effective as well. Proper function of mutant p53 depends on interactions with the Hsp90 chaperone complex and HDAC6. The Hsp90/HDAC6 chaperone machine is significantly upregulated in tumors compared with normal tissues and function as a major determinant of mutant p53 stabilization [192]. Inhibitors that target Hsp90 or HDAC6 both show positive results in depleting mutant p53 in preclinical trials [193, 194]. Repression of the mevalonate pathway by statins, which inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, not only abrogates binding of multiple p53 mutants to DNAJA1 and the HSP40 complex but also increases mutant p53 degradation through interaction and ubiquitination by the co-chaperone carboxyl terminus Hsp70/90 interacting protein (CHIP) E3 ubiquitin ligase [195].

Developments in iPSCs methodologies will likely improve drug discovery for p53-related therapies. Since LFS patient-derived iPSCs would provide a more reliable genetic background for drug efficacy and toxicity screen, failure in translation from animal models to humans can be reduced. Moreover, LFS iPSCs can be differentiated into multiple cell lineages, each of which can serve as a tumor model. As a result, a p53 drug screen can be narrowed down to one specific tumor type, increasing the fidelity of the system and the expected success rate. Already, this approach has shown promise in other genes. Engineered human embryonic stem cell (ESC)-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and neural stem cells (NSCs) have been used to study and model diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPGs) [196] and GBM [197] respectively. Both of these studies identified novel potential drugs for brain tumors. As applications of iPSC models to cancer increase, the technology will likely gain increasing importance in developing and guiding cancer treatment [198].

Personalizing cancer therapy through precise genome editing

Advances in genomics have led to an exponential increase in available cancer genomic data and finally directed us to the gene mutations driving cancer. In some cases mutations found in only a fraction of cells extracted from a single patient tumor sample can be identified. Still, translation of this knowledge into personalized therapy is far from reality. One of the biggest bottlenecks is how to convert knowledge of a specific genomic alteration into a therapeutic assay against which therapies can be targeted [199]. Hundreds of p53 mutations have been detected in both germline [26] and sporadic tumors [200], but collecting samples from all these patients and assembling them into a bio-bank of LFS iPSCs would entail a substantial research endeavor.

Precise genome editing tools such as zinc finger nuclease (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeat/Cas9 (CRISPR/Cas9) present an alternative way around this bottleneck. These site-specific nucleases (SSNs) have proved their power in facilitating site-directed mutagenesis as well as correcting mutations in PSCs and are beginning to revolutionize fields of biomedical research [201–203]. By increasing the diversity of genetic diseases available to study and model, these genome editing tools are facilitating discovery of therapeutics.

Specific p53 mutations can be engineered into WT pluripotent stem cells (PSCs; including ESCs and iPSCs) utilizing genomic editing tools and allow for a wide and varied collection of mutant p53 PSCs against which candidate drugs can be screened and tested. Establishment of such a collection of mutant p53 PSCs will allow the testing of existing compounds that target specific p53 mutants (discussed above) on a wider range of p53 mutants (Figure 3). This collection will also facilitate screening and testing of novel potential therapeutics in a more targeted fashion. Finally, with preclinical data that clearly defines the p53 mutants for which a therapy would be expected to be successful, the cost of conducting clinical trials can be dramatically through better patient stratification.

While iPSC technology offers unique advantages in modeling disease down to a particular patient’s genetic background, this specificity can be a double-edged sword. Genetic diversity between individuals often complicates the interpretation of findings across multiple iPSC lines. On the other hand, genome-edited PSCs, either from well-characterized ESCs or iPSCs from healthy subjects have proved to be useful in revealing disease-relevant phenotypic differences while minimizing the variability found across patient-derived iPSC lines. For instance, introduction of KCNH2 mutations in human ESCs [199] or integration of KCNQ1 and KCNH2 dominant negative mutations [204] in WT PSCs recapitulates the long QT syndrome phenotype when the PSCs are differentiated to cardiomyocytes. Deletion of kidney disease genes PKD1 or PKD2 induces cyst formation in a PSC-derived kidney organoid model, recapitulating the human disease phenotype [205]. These successful research examples suggest the potential of PSCs with various p53 mutations in elucidating pathogenesis of mutant p53 associated cancers, and facilitating identification of potential drug targets for tumors with different p53 mutations.

Intersection of the LFS iPSC model with new methodologies: organoids and organs-on-chip

Advances in 3D culture technology allow generation of organoids from PSCs and adult stem cells (AdSCs). These 3D organoids better mimic the physiologic structure and functions of organs than 2D culture and have been used to model normal development as well as human diseases [206, 207]. Interestingly, the 3D organoid culture system has been extended to primary cancer culture, in which cancer organoids can be generated from primary tumors, including colon [208, 209], pancreatic [210] and prostate cancers [211]. Both normal and cancer organoids provide a unique platform for drug sensitivity and toxicity testing. Mature proximal tubular cells within iPSCs-derived kidney organoids undergo apoptosis after cisplatin treatment, indicating that kidney organoids could be used to test drug nephrotoxicity [212]. Cystic fibrosis patient-derived rectal organoids have been used to characterize response to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-modulating drugs, suggesting that organoids can be prospectively used to identifying drug responders [213]. A team from the Netherlands generated a living organoid biobank from colorectal cancer patients and demonstrated the feasibility of high-throughput drug screening while highlighting, as an example of potential personalized therapy, the sensitivity of one line to alterations in Wnt signaling [209].

Carcinogenesis and cancer progression can also be modeled using organoids. Introducing mutations of tumor suppressors APC, SMAD4, TP53 and the oncogene KRAS into normal intestinal organoids led to malignant transformation both in vitro and in vivo [214, 215]. Neoplastic transformation was also observed when expressing mutant KRAS and/or TP53 in normal PSC-derived pancreatic organoids [216]. Knocking down Tgfbr2 in Tp53−/−, Cdh1−/− murine stomach organoids resulted in a metastatic phenotype in vivo [217]. The classic “adenoma to carcinoma” model has been recapitulated by sequentially creating cancer-driving mutations in human intestinal organoids [218].

These advances in 3D organoid systems lead us to postulate that integration of the LFS iPSC model with the organoid platform will provide additional opportunities for deciphering the pathogenesis of mutant p53-associated cancers and identifying potential druggable targets (Figure 3). One of the promising combinations will be using 3D cerebral organoids to study LFS-associated brain tumors. PSC-derived cerebral organoids can be grown in a spinning bioactor system, which enables rapid and abundant generation of a “mini-brain” [219]. Cerebral organoids have been utilized to model neurodevelopmental disease, such as microcephaly [219, 220] and lissencephaly [221], and have also been used to identify antiviral compounds against Zika virus [175]. LFS iPSC-derived cerebral organoids hold potential in brain tumor modeling and may clarify the origins of GBM in affected patients.

Recently, researchers have developed organs-on-chip systems in an attempt to accurately mimic the cellular environment [222, 223]. Organ-on-chip systems integrate cell culture with microfabrication and microfluidics technologies and allow cells to be cultured in connected chambers. The term organs-on-chip was subsequently used to describe growth of multiple organs on a chip, in which various living human cells are cultured in a microenviroment designed to replicate the in vivo milieu [222]. Organs-on-chip can represent key functional units of human organs or tissues. With the goal of mimicking the entire human body on a chip, this biomimetic system has great value in drug discovery and testing [224, 225]. While many early organs-on-chips were developed from primary or transformed cell lines [226–231], newer systems incorporate iPSCs and relevant differentiated tissues into microfluidic devices [232–234]. Mathur et al. grew 3D cardiac tissue within a microfluidic device which mimics the blood flow and endothelial barrier. This human iPSC-based cardiac microphysiology system proved particularly valuable in predicting drug-induced cardiotoxicity [232]. In addition, functional differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells directly on microfluidic devices has recently been reported. Through optimal delivery of differentiation medium, Giovanni et al [235] generated functional cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes that showed an expected response to defined drug treatments. We foresee this powerful technique providing invaluable information to clarify important missing pieces in the p53/LFS/cancer/development puzzle.

Concluding Remarks

The link between LFS and TP53 germ-line mutation has made this hereditary cancer syndrome a unique and useful model in studying p53-associated cancers. Application of patient-derived iPSCs to LFS-associated cancers will be of great value in: (i) recapitulating the phenotype of LFS-associated cancer; (ii) elucidating the pathogenesis of mutant p53-associated cancers; (iii) discovering novel mutant p53 gain-of-function: (iv) identifying potential drug targets for mutant p53; (v) providing unlimited rearrangement-free cell sources for novel drug discovery and compound screening; and (vi) facilitating in vitro efficacy and toxicity testing for preclinical compounds. In addition, creating specific p53 mutations in WT PSCs using precise genome editing methodologies will become a valuable resource for developing precision cancer therapy targeting specific p53 gain-of-function mutations.

The variability between individual iPSCs could hinder a precise measurement of a mutation-associated phenotype. Generating isogenic control cell lines for disease-specific iPSCs will help reduce variability caused by genetic background. Precise genome editing enables creation of isogenic pairs of disease-specific and control iPSCs whose only difference is a disease-causing mutation [236]. The isogenic pairs of iPSCs generated from patients can also be used to test drug toxicity and predict treatment response, and the in vitro testing results for each patient will facilitate individual precision treatment.

The fast-growing 3D organoids technology will be increasingly central to cancer models and will assist in identifying and testing potential anti-cancer drugs. The high structural organization afforded by 3D organoids better mimics organ function than 2D culture, and the complexity of this microenvironment in cancer development cannot be ignored. Recent progress has been made in constructing 3D blood vessels from PSC-derived endothelial and pericytes [237]. The microengineered blood vessels can be lined inside a microfluidic device, which can be used to test drug efficacy and study interaction between vascular cells. In the future, vasculature and immune cells may be integrated into a larger tissue construct to advance the development of organs-on-chips. Inclusion of the microenvironment into PSC derivatives will offer exciting opportunities to model cancer from a more complex dimension.

In conclusion, LFS disease models offer unique platforms to study and model mutant p53-associated cancers (see Outstanding Questions). Integration of LFS iPSCs and engineered p53 mutant PSCs to cancer modeling will offers a valuable source for mechanistic study and drug discovery. We look forward to the wider application of the LFS iPSC model, including to 3D organoid and organ-on-chip technologies, in future studies.

Trends Box.

LFS is a cancer hereditary syndrome caused by TP53 germ-line mutations. This syndrome serves as a useful model to study mutant p53-associated cancers. LFS patient-derived iPSCs offer several advantages compared to other LFS disease models, including unlimited supply of tissue, a human platform, and access to the heterogeneity of disease across multiple cell types. This system enables cancer modeling and facilitates in vitro drug testing.

LFS iPSCs and engineered p53 mutant PSCs can be used to discover drugs that target mutant p53 and its related pathways. LFS iPSCs can also assist in the development of in vitro assays, which are of great value in drug screening and testing in a dish. Marriage of LFS iPSC models to precise genome editing, 3D based cell culture and organ-on-chip systems will facilitate cancer modeling and anti-cancer drug discovery in a more comprehensive and nuanced way than otherwise possible.

Outstanding Questions.

Do cancers derived from LFS iPSC models harbor intra-tumor heterogeneity resembling the heterogeneity found in patient primary tumors?

Can LFS iPSCs comprehensively recapitulate LFS malignancies in the absence of the microenvironment found inside human bodies?

Can PSCs engineered to express p53 mutants recapitulate the disease malignancies demonstrated to exist in LFS patients and in LFS iPSCs, or is there something else unique about the genetic background of LFS?

Can LFS iPSC-derived tumors offer a practical “disease-in-a-dish” platform for novel cancer therapeutics discovery?

Can LFS iPSC-derived tumors serve as an alternative PDTX model?

Acknowledgments

We sincerely apologize to authors whose excellent studies we could not include owing to space limitations. R. Z. is supported by UTHealth Innovation for Cancer Prevention Research Training Program Pre-doctoral Fellowship (Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas grant # RP160015). D.-F.L. is a Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) scholar in Cancer Research and is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Pathway to Independence Award R00 CA181496 and CPRIT Award RR160019.

Glossary

- Knudson’s “two-hit” theory

Alfred G. Knudson formulated this theory in 1971 by analyzing cases of retinoblastoma which occurs as autosomal dominant inherited disease and sporadically. The fact that inherited retinoblastoma occurs at a younger age than the sporadic case and tumors often affect both eyes, lead to Knudson’s hypothesis: the first hit is present in the germ-line, and the first hit (germ-line mutations) at the susceptibility locus is not insufficient for tumor formation; a second hit (somatic mutation) is necessary for promoting tumor formation. Knudson’s “two-hit” theory leads to identification of RB1 as a tumor suppressor gene and also provides evidence of other tumor suppressive genes, such as WT1, APC and TP53

- p53 loss of function

WT p53 can exert a tumor-suppressive effect by regulating cellular functions such as cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis and DNA damage repair. When the TP53 gene undergoes mutations, the tumor-suppressive effect of WT p53 can be abrogated or completely lost, which contributes to the course of tumor development

- Mutant p53 dominant-negative effect

certain p53 mutants, when expressed together with WT p53, can inactivate WT p53 and overcome its tumor-suppressive functions. This dominant-negative effect of mutant p53 over WT p53 protein can be achieved by forming mixed tetramers with diminished transactivation activity, therefore promoting tumorigenesis

- Mutant p53 gain-of-function

certain p53 mutants possess functions of their own entirely independent of those observed in WT p53. These newly gained functions are usually oncogenic, contributing to cancer progression from various aspects

- HUPKI mouse model

The human p53 knock-in mouse model is constructed using gene-targeting technology to generate a mouse strain harboring the human wild-type TP53 genome in both copies of the mouse Trp53 gene locus. Trp53 exons 4–9 are replaced with the human gene TP53 exons 4–9

- Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

Pluripotent stem cells derived from differentiated somatic cells through somatic reprogramming by defined factors (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and c-MYC)

- Patient-derived tumor xenograft (PDTX)

xenograft model created when surgically resected tumor samples from patients are engrafted directly into immunodeficient mouse. Tumors in the PDTX model can be maintained through serial passaging in mice. PDTXs recapitulate molecular, genetic and histological characteristics of the primary tumors of origin; therefore they offer an excellent in vivo preclinical platform for novel cancer therapeutics discovery

- Conditional reprogramming (CR)

A cell culture methodology applied to rapidly and efficiently establish cells for long-term propagation using normal and cancer cells taken directly from patients

- Organoid

a 3D culture system that enables a collection of multiple organ-specific cells self-organizes into organ-bud structures. 3D-cultured organoids mimic better of the microanatomy of organs and are capable of recapitulating specific organ functions, enabling experimental study of otherwise inaccessible tissue

- Organs-on-Chip

a microfluidic device containing one or more culture chambers connected with channels in which culture media flow. The cells cultured in each chamber can proliferate, differentiate and mature in a more physiological environment, and mimic the smallest functional subunits of human tissue or organ. Incorporation of human iPSCs, 3D culture and vasculature in the microfluidic device makes organs-on-chip a promising platform for drug screening and discovery

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this review.

References

- 1.Li FP, Fraumeni JF., Jr Rhabdomyosarcoma in children: epidemiologic study and identification of a familial cancer syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1969;43(6):1365–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li FP, Fraumeni JF., Jr Soft-tissue sarcomas, breast cancer, and other neoplasms. A familial syndrome? Ann Intern Med. 1969;71(4):747–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-71-4-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li FP, et al. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 1988;48(18):5358–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birch JM, et al. Prevalence and diversity of constitutional mutations in the p53 gene among 21 Li-Fraumeni families. Cancer Res. 1994;54(5):1298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichols KE, et al. Germ-line p53 mutations predispose to a wide spectrum of early-onset cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10(2):83–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorrell AD, et al. Tumor protein p53 (TP53) testing and Li-Fraumeni syndrome : current status of clinical applications and future directions. Mol Diagn Ther. 2013;17(1):31–47. doi: 10.1007/s40291-013-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chompret A, et al. P53 germline mutations in childhood cancers and cancer risk for carrier individuals. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(12):1932–7. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu CC, et al. Joint effects of germ-line p53 mutation and sex on cancer risk in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cancer Res. 2006;66(16):8287–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hisada M, et al. Multiple primary cancers in families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(8):606–11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.8.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bougeard G, et al. Revisiting Li-Fraumeni Syndrome From TP53 Mutation Carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(21):2345–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zebisch A, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with TP53 germ line mutations. Blood. 2016;128(18):2270–2272. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-732610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heymann S, et al. Radio-induced malignancies after breast cancer postoperative radiotherapy in patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:104. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Limacher JM, et al. Two metachronous tumors in the radiotherapy fields of a patient with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2001;96(4):238–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemp CJ, et al. p53-deficient mice are extremely susceptible to radiation-induced tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 1994;8(1):66–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle JM, et al. The relationship between radiation-induced G(1)arrest and chromosome aberrations in Li-Fraumeni fibroblasts with or without germline TP53 mutations. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(2):293–6. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villani A, et al. Biochemical and imaging surveillance in germline TP53 mutation carriers with Li-Fraumeni syndrome: 11 year follow-up of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1295–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malkin D, et al. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990;250(4985):1233–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1978757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srivastava S, et al. Germ-line transmission of a mutated p53 gene in a cancer-prone family with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Nature. 1990;348(6303):747–9. doi: 10.1038/348747a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varley JM. Germline TP53 mutations and Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2003;21(3):313–20. doi: 10.1002/humu.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olivier M, et al. The IARC TP53 database: new online mutation analysis and recommendations to users. Hum Mutat. 2002;19(6):607–14. doi: 10.1002/humu.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frebourg T, et al. Germ-line p53 mutations in 15 families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56(3):608–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varley JM, et al. Germ-line mutations of TP53 in Li-Fraumeni families: an extended study of 39 families. Cancer Res. 1997;57(15):3245–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shlien A, et al. Excessive genomic DNA copy number variation in the Li-Fraumeni cancer predisposition syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(32):11264–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802970105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bougeard G, et al. Screening for TP53 rearrangements in families with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome reveals a complete deletion of the TP53 gene. Oncogene. 2003;22(6):840–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chompret A, et al. Sensitivity and predictive value of criteria for p53 germline mutation screening. J Med Genet. 2001;38(1):43–7. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouaoun L, et al. TP53 Variations in Human Cancers: New Lessons from the IARC TP53 Database and Genomics Data. Hum Mutat. 2016;37(9):865–76. doi: 10.1002/humu.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogelstein B, et al. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408(6810):307–10. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laptenko O, Prives C. Transcriptional regulation by p53: one protein, many possibilities. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(6):951–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bieging KT, et al. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(5):359–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matoba S, et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312(5780):1650–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bensaad K, Vousden KH. p53: new roles in metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(6):286–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connor JC, et al. A novel antioxidant function for the tumor-suppressor gene p53 in the retinal ganglion cell. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(10):4237–44. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bensaad K, Vousden KH. Savior and slayer: the two faces of p53. Nat Med. 2005;11(12):1278–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1205-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crighton D, et al. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126(1):121–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tasdemir E, et al. Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(6):676–87. doi: 10.1038/ncb1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roger L, et al. Control of cell migration: a tumour suppressor function for p53? Biol Cell. 2006;98(3):141–52. doi: 10.1042/BC20050058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teodoro JG, et al. p53-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis through up-regulation of a collagen prolyl hydroxylase. Science. 2006;313(5789):968–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1126391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, et al. p53 functions as a negative regulator of osteoblastogenesis, osteoblast-dependent osteoclastogenesis, and bone remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2006;172(1):115–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Li B. p53 control of bone remodeling. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111(3):529–34. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pant V, et al. The p53 pathway in hematopoiesis: lessons from mouse models, implications for humans. Blood. 2012;120(26):5118–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-356014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yi L, et al. Multiple roles of p53-related pathways in somatic cell reprogramming and stem cell differentiation. Cancer Res. 2012;72(21):5635–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng H, et al. p53 and Pten control neural and glioma stem/progenitor cell renewal and differentiation. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1129–33. doi: 10.1038/nature07443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray-Zmijewski F, et al. p53/p63/p73 isoforms: an orchestra of isoforms to harmonise cell differentiation and response to stress. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(6):962–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He Y, et al. p53 loss increases the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33(4):1304–19. doi: 10.1002/stem.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H, et al. p53 regulates neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation via BMP-Smad1 signaling and Id1. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(6):913–27. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McConnell AM, et al. p53 Regulates Progenitor Cell Quiescence and Differentiation in the Airway. Cell Rep. 2016;17(9):2173–2182. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cottle DL, et al. p53 activity contributes to defective interfollicular epidermal differentiation in hyperproliferative murine skin. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(1):204–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Q, et al. The p53 Family Coordinates Wnt and Nodal Inputs in Mesendodermal Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20(1):70–86. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee DF, et al. Regulation of embryonic and induced pluripotency by aurora kinase-p53 signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(2):179–94. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong H, et al. Suppression of induced pluripotent stem cell generation by the p53-p21 pathway. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1132–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawamura T, et al. Linking the p53 tumour suppressor pathway to somatic cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1140–4. doi: 10.1038/nature08311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarig R, et al. Mutant p53 facilitates somatic cell reprogramming and augments the malignant potential of reprogrammed cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207(10):2127–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137(3):413–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Janicke RU, et al. The dark side of a tumor suppressor: anti-apoptotic p53. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(6):959–76. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim E, et al. Wild-type p53 in cancer cells: when a guardian turns into a blackguard. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martins CP, et al. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell. 2006;127(7):1323–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ventura A, et al. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445(7128):661–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xue W, et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445(7128):656–60. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheok CF, et al. Translating p53 into the clinic. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(1):25–37. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olivier M, et al. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(1):a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kandoth C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502(7471):333–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hohenstein P. Tumour suppressor genes–one hit can be enough. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(2):E40. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petitjean A, et al. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(6):622–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weisz L, et al. Transcription regulation by mutant p53. Oncogene. 2007;26(15):2202–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song H, et al. p53 gain-of-function cancer mutants induce genetic instability by inactivating ATM. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(5):573–80. doi: 10.1038/ncb1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Caulin C, et al. An inducible mouse model for skin cancer reveals distinct roles for gain- and loss-of-function p53 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(7):1893–901. doi: 10.1172/JCI31721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hingorani SR, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(5):469–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Valenti F, et al. Gain of function mutant p53 proteins cooperate with E2F4 to transcriptionally downregulate RAD17 and BRCA1 gene expression. Oncotarget. 2015;6(8):5547–66. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Samassekou O, et al. Different TP53 mutations are associated with specific chromosomal rearrangements, telomere length changes, and remodeling of the nuclear architecture of telomeres. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53(11):934–50. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang X, et al. A novel PTEN/mutant p53/c-Myc/Bcl-XL axis mediates context-dependent oncogenic effects of PTEN with implications for cancer prognosis and therapy. Neoplasia. 2013;15(8):952–65. doi: 10.1593/neo.13376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ali A, et al. Gain-of-function of mutant p53: mutant p53 enhances cancer progression by inhibiting KLF17 expression in invasive breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2014;354(1):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dong P, et al. Mutant p53 gain-of-function induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition through modulation of the miR-130b-ZEB1 axis. Oncogene. 2013;32(27):3286–95. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Atema A, Chene P. The gain of function of the p53 mutant Asp281Gly is dependent on its ability to form tetramers. Cancer Lett. 2002;185(1):103–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu K, et al. TopBP1 mediates mutant p53 gain of function through NF-Y and p63/p73. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(22):4464–81. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05574-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.El-Hizawi S, et al. Induction of gene amplification as a gain-of-function phenotype of mutant p53 proteins. Cancer Res. 2002;62(11):3264–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matas D, et al. Integrity of the N-terminal transcription domain of p53 is required for mutant p53 interference with drug-induced apoptosis. EMBO J. 2001;20(15):4163–72. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Di Agostino S, et al. Gain of function of mutant p53: the mutant p53/NF-Y protein complex reveals an aberrant transcriptional mechanism of cell cycle regulation. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(3):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gaiddon C, et al. A subset of tumor-derived mutant forms of p53 down-regulate p63 and p73 through a direct interaction with the p53 core domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(5):1874–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1874-1887.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Murphy KL, et al. A gain of function p53 mutant promotes both genomic instability and cell survival in a novel p53-null mammary epithelial cell model. FASEB J. 2000;14(14):2291–302. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0128com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scian MJ, et al. Tumor-derived p53 mutants induce oncogenesis by transactivating growth-promoting genes. Oncogene. 2004;23(25):4430–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marin MC, et al. A common polymorphism acts as an intragenic modifier of mutant p53 behaviour. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):47–54. doi: 10.1038/75586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Muller PA, et al. Mutant p53 enhances MET trafficking and signalling to drive cell scattering and invasion. Oncogene. 2013;32(10):1252–65. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dong P, et al. Elevated expression of p53 gain-of-function mutation R175H in endometrial cancer cells can increase the invasive phenotypes by activation of the EGFR/PI3K/AKT pathway. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:103. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adorno M, et al. A Mutant-p53/Smad complex opposes p63 to empower TGFbeta-induced metastasis. Cell. 2009;137(1):87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Coffill CR, et al. Mutant p53 interactome identifies nardilysin as a p53R273H-specific binding partner that promotes invasion. EMBO Rep. 2012;13(7):638–44. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Muller PA, et al. Mutant p53 drives invasion by promoting integrin recycling. Cell. 2009;139(7):1327–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Noll JE, et al. Mutant p53 drives multinucleation and invasion through a process that is suppressed by ANKRD11. Oncogene. 2012;31(23):2836–48. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yeudall WA, et al. Gain-of-function mutant p53 upregulates CXC chemokines and enhances cell migration. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(2):442–51. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vaughan CA, et al. p53 mutants induce transcription of NF-kappaB2 in H1299 cells through CBP and STAT binding on the NF-kappaB2 promoter and gain of function activity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;518(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ji L, et al. Mutant p53 promotes tumor cell malignancy by both positive and negative regulation of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) pathway. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(18):11729–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.639351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Subramanian M, et al. A mutant p53/let-7i-axis-regulated gene network drives cell migration, invasion and metastasis. Oncogene. 2015;34(9):1094–104. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fontemaggi G, et al. The execution of the transcriptional axis mutant p53, E2F1 and ID4 promotes tumor neo-angiogenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(10):1086–93. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Capponcelli S, et al. Evaluation of the molecular mechanisms involved in the gain of function of a Li-Fraumeni TP53 mutation. Hum Mutat. 2005;26(2):94–103. doi: 10.1002/humu.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khromova NV, et al. p53 hot-spot mutants increase tumor vascularization via ROS-mediated activation of the HIF1/VEGF-A pathway. Cancer Lett. 2009;276(2):143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pfister NT, et al. Mutant p53 cooperates with the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex to regulate VEGFR2 in breast cancer cells. Genes Dev. 2015;29(12):1298–315. doi: 10.1101/gad.263202.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Freed-Pastor WA, et al. Mutant p53 disrupts mammary tissue architecture via the mevalonate pathway. Cell. 2012;148(1–2):244–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang C, et al. Tumour-associated mutant p53 drives the Warburg effect. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2935. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhou G, et al. Gain-of-function mutant p53 promotes cell growth and cancer cell metabolism via inhibition of AMPK activation. Mol Cell. 2014;54(6):960–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li X, et al. Anti-cancer efficacy of SREBP inhibitor, alone or in combination with docetaxel, in prostate cancer harboring p53 mutations. Oncotarget. 2015;6(38):41018–32. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Weisz L, et al. Mutant p53 enhances nuclear factor kappaB activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(6):2396–401. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cooks T, et al. Mutant p53 prolongs NF-kappaB activation and promotes chronic inflammation and inflammation-associated colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(5):634–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Di Minin G, et al. Mutant p53 reprograms TNF signaling in cancer cells through interaction with the tumor suppressor DAB2IP. Mol Cell. 2014;56(5):617–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ubertini V, et al. Mutant p53 gains new function in promoting inflammatory signals by repression of the secreted interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Oncogene. 2015;34(19):2493–504. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Freed-Pastor WA, Prives C. Mutant p53: one name, many proteins. Genes Dev. 2012;26(12):1268–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.190678.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Muller PA, Vousden KH. p53 mutations in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(1):2–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sigal A, Rotter V. Oncogenic mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor: the demons of the guardian of the genome. Cancer Res. 2000;60(24):6788–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Strano S, et al. Mutant p53 proteins: between loss and gain of function. Head Neck. 2007;29(5):488–96. doi: 10.1002/hed.20531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Strano S, et al. Mutant p53: an oncogenic transcription factor. Oncogene. 2007;26(15):2212–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brosh R, Rotter V. When mutants gain new powers: news from the mutant p53 field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(10):701–13. doi: 10.1038/nrc2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Muller PA, Vousden KH. Mutant p53 in cancer: new functions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):304–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Olivier M, et al. Recent advances in p53 research: an interdisciplinary perspective. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oren M, Rotter V. Mutant p53 gain-of-function in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(2):a001107. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lozano G. The oncogenic roles of p53 mutants in mouse models. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(1):66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Peters J. The role of genomic imprinting in biology and disease: an expanding view. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(8):517–30. doi: 10.1038/nrg3766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Holm TM, et al. Global loss of imprinting leads to widespread tumorigenesis in adult mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(4):275–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Murrell A. Genomic imprinting and cancer: from primordial germ cells to somatic cells. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:1888–910. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]