Abstract

Purpose

To characterize the relaxation properties of reactive oxygen species (ROS) for the development of endogenous ROS contrast MRI.

Materials and Methods

ROS producing phantoms and animal models were imaged at 9.4T MRI to obtain T1 and T2 maps. Egg white samples treated with varied concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were used to evaluate the effect of produced ROS in T1 and T2 for up to 4 hours. pH and temperature changes due to H2O2 treatment in egg white were also monitored. The influences from H2O2 itself and oxygen were evaluated in solution producing no ROS in bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution. In addition, dynamic temporal changes of T1 in H2O2 treated egg white samples were used to estimate ROS concentration over time and hence the detection sensitivity of relaxation based endogenous ROS MRI. The relaxivity of ROS was compared with that of Gd-DTPA as a reference. Finally, the feasibility of in vivo ROS MRI with T1 mapping acquired using inversion recovery sequence was demonstrated with a well-established rotenone-treated mouse model (n = 6).

Results

pH and temperature changes in treated egg white sample were insignificant (< 0.1 unit and < 1°C, respectively). T1 relaxation time in the H2O2-treated egg white was reduced significantly (p<0.05), while there was insignificant reduction in T2 (<10%). In the H2O2-treated BSA solution that produce no ROS, there was small change in T1 due to H2O2 itself (±1%), although a significant T2-shortening effect was observed (>10%, p<0.05). Also there was small reduction in T1 (13±1%, p>0.05) and T2 (1±2%, p>0.05) from molecular oxygen. The detection sensitivity of ROS MRI was estimated around 10 pM. The T1 relaxivity of ROS was found to be much higher than that of Gd-DTPA (3.4×107 vs. 0.9 s−1·mM−1). Finally significantly reduced T1 was observed in rotenone-treated mouse brain (5.1±2.5%, p<0.05).

Conclusions

We have demonstrated in the study that endogenous ROS MRI based on their paramagnetic effects has the sensitivity for in vitro and in vivo applications.

Keywords: Free radicals, Reactive oxygen species, Relaxation time, MRI, Paramagnetic effect

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including singlet oxygen(O2(1Δg)), superoxide (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (.OH), have long been subjects of study due to their central role in cell signaling, aging process, and in pathogenesis of a variety of diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.(1–5) ROS can be divided into radical species (e.g. .OH) and non-radical species (e.g. H2O2). They are mainly produced by several different enzyme systems (e.g. cytosolic enzyme) and by the mitochondrial complex I and III.(6) They can react readily with any surrounding tissue component (e.g. lipids, proteins, and DNA)(2) and can initiate complicated chain processes with high biological impact (e.g. Haber-Weiss or Fenton reactions).(7)

The high reactivity and short lifetime of ROS make them very challenging to detect. For example, the lifetime of singlet oxygen, superoxide, and hydroxyl radical in aqueous solutions is within the μs regime.(8–13) In addition, the in vivo concentration of ROS is generally low (μM level),(14) making their detection more challenging. In order to measure ROS, several methods have been developed including optical redox scanning(15) and exogenous contrast MR based methods.(16–21) Optical redox scanning acquires ex vivo fluorescence images from endogenous reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and oxidized flavoproteins (Fp) in order to map tissue redox state that is related to ROS-induced oxidative stress.(15) However, this technique is invasive and only applicable to ex vivo tissues. MR-based methods such as Overhauser-enhanced MRI (OMRI)(16), proton electron double resonance (PEDRI),(17) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)(18) obtain contrast from the Overhauser effect of irradiated radicals, although requiring exogenous reagents to trap such radicals. Other MRI methods under development also rely on exogenous contrast agents with paramagnetic metallic ions (e.g. Gd3+ and Eu3+).(19–21) Nevertheless, ideal ROS imaging should be endogenous and able to determine their changes in vivo with high spatial resolution and sensitivity.

The power of MRI resides in providing superb soft-tissue structural contrast for clinical diagnosis. In addition to the anatomical information provided by MRI, molecular information may also be obtained. ROS with unpaired electrons have potential to influence tissue relaxation properties that can be used for the quantification of ROS with endogenous contrast MRI. This study therefore investigated the MRI relaxation properties of ROS produced from fresh egg white tissues treated with various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). When H2O2 is added to egg white, hydroxyl radical can be produced for hours in the presence of natural transition metals (such as iron) through Fenton reactions (Equation 1).(22)

| [1] |

In addition, the detection sensitivity of ROS MRI was quantified and its in vivo feasibility demonstrated to pave the way for clinical translation.

Materials and Methods

Egg white was manually extracted from fresh hen eggs and was gently stirred for 2–3 min. Samples were then placed into test-tubes and were treated with a bolus of H2O2 solution at a volume ratio of 1 (H2O2 solution) to 11 (pure egg white). The H2O2 solution was proportionally diluted from 30% hydrogen peroxide with a density ~1.1 kg/L (Fisher Scientific Co., Hampton, NH, USA) to have final concentrations of H2O2 in egg white at 0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.25 v/v% equivalent to 0, 8.1, 16.2, 32.4, and 80.9 mM (n=5). After 1 hour of treatment, samples were MRI scanned at 9.4 T at room temperature (~21°C). In a separate set of samples, the pH and temperature of H2O2-treated egg white were monitored using a Hanna Instruments meter (model HI 2211, Hanna instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA) for up to 4 hours.

The influence on T1 and T2 relaxation times by H2O2 itself was evaluated in 20% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Fraction V powder, A2153, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) protein solutions prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (n=3) at room temperature. This phantom was used to avoid ROS production given that BSA samples contain no transition metals to catalyze Fenton reactions. The BSA samples were MRI scanned after being treated with same concentrations of H2O2 as in the egg white studies. For evaluation of MR effects from molecular oxygen, one of the end products in Fenton reactions, separate BSA solutions were bubbled with 100% oxygen gas (0.1 L/min) at room temperature for 15, 30, 45, and 60 min and compared with samples without oxygen bubbling (n=5).

For the determination of ROS detection sensitivity using MRI, separated egg white samples (n=6) treated with 0.25 v/v% H2O2 were longitudinally monitored for up to 4 hours. As described in the Fenton reactions (Equation 1), one molecule H2O2 produces one hydroxyl radical (.OH) on average. Hence, the overall ROS production over time is equal to the total initial H2O2. The produced ROS concentration over time can be modeled with the pseudo-first order reaction kinetics(22):

| [2] |

Where [ROS]0 is the concentration of ROS immediately after (t = 0) the addition of H2O2, is the kinetic coefficient (rate constant of ROS production), and is time. Suggested by our experimental data that relaxation time change and ROS concentration are correlated, the dynamic changes of relaxation time is expected to follow the same reaction kinetics (Equation 2). Since the areas under the curves is equivalent to the total ROS production, that is equivalent to the initial H2O2 concentration, [ROS] at any given time can be quantified from curve fitting. The lifetime of produced ROS was assumed to be about 1 μs(13), and the detection sensitivity was therefore determined as the detectable concentration when contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) > 5, according to the Rosen criteria.(23) In this study, CNR was calculated from magnitude changes of T1-weighted MRI images between treated and control samples divided by the standard deviation of a user defined noise region (background) as the following,

| [3] |

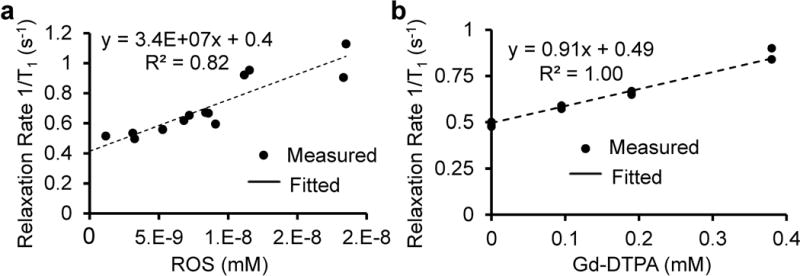

Furthermore, the estimated ROS concentrations over time and the corresponding T1 relaxation times were then used to derive T1-relaxivity of ROS. T1 relaxivity of ROS was compared to that of Gd-DTPA, the most common paramagnetic agent in the MRI clinic, as a reference. The T1 relaxivity of Gd-DTPA was derived from T1 maps of egg white samples (n=3) mixed with various concentrations of Gd-DTPA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (0, 0.095, 0.19, and 0.38 mM).

For in vivo detection of ROS at the steady-state concentration, we imaged mice (CD-1, male, n=6, 12 weeks old, 50±6 g body weight) treated with rotenone solutions (An IP bolus injection, 20 mg/kg body weight) that were prepared based on previous reports.(24,25) In brief, rotenone dissolved in chloroform (>99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was mixed with 4% of carboxymethylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to render a final concentration of 1.25 mg/mL. MRI of mouse brains was performed at baseline and 1.5 hours post rotenone injection. In addition, we imaged another group of mice (CD-1, male, n=3, 12 weeks old, 50±8 g body weight) treated with PBS with same injection volume for rotenone group as reference. All experimental procedures and protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

MRI of egg white samples and mouse brains were performed on an Agilent 9.4-T horizontal bore MRI scanner (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with an 11-cm gradient coil (1000 mT/m, 0.13 ms) and with a 39-mm ID birdcage quadrature proton RF coil. MRI protocols consisted of anatomical imaging and T1/T2 mapping. High resolution multi-slice anatomical images were acquired with a fast spin echo sequence and parameters: TE/TR = 8.4/2000 ms; echo-train length = 8; field of view (FOV) = 25 × 25 mm2; matrix size = 256 × 256; slice thickness = 1 mm; number of average = 4. With the anatomical brain images, a central brain slice was selected as the imaging slice for further MRI scan to obtain T1 and T2 maps. For T1 mapping, an inversion recovery fast spin echo sequence with variable inversion times (TI = 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2, and 5 s) was used (~7 min scan time). Other parameters include TE/TR = 5 ms/10 s, echo train length = 8, FOV = 25 × 25 mm2, and matrix size = 64 × 64. For T2 mapping, a fast spin echo sequence with variable echo times was used (~4 min scan time). Imaging parameters were TR = 6s, echo train length = 8, TE= 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 200, and 500 ms, FOV = 25 × 25 mm2, and matrix size = 64 × 64. For the calculation of CNR due to H2O2 treatment, T1 weighted images were acquired using a single-shot Fast Low-Angle Shot (FLASH) sequence with parameters including TE/TR = 3.5/300 ms, flip angle = 20°, FOV = 25×25 mm2, and matrix size = 128 × 128. Image processing and data analyses were all performed using home-built programs in MATLAB (R2012b, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Comparison of results from treated and untreated egg white samples was performed using unpaired one-tailed Student’s t-tests. The reaction kinetics curve-fitting was performed using the non-linear least squares procedure in MATLAB (R2012b, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). The quality of fit was evaluated by the R-squared (26). For the animal study, paired one-tailed Student’s t-tests were used. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Values were presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation Error (SE).

Results

Changes in pH and temperature due to Fenton reactions in H2O2 treated egg white samples were very small (< 0.1 unit and < 1 °C, respectively). T1 relaxation time of egg white samples was found to reduce with H2O2 treatment (Fig. 1a–b), while the reduction in T2 relaxation time was negligible (<10%) (Fig. 1c–d). On the other hand, in the BSA samples producing no ROS, the reduction of T1 relaxation time due to H2O2 was negligible (±1%) (Fig. 2a–b). On the other hand, the T2 relaxation time of BSA was greatly decreased with H2O2 treatment (>10%, p<0.05) (Fig. 2c–d). Figure 3 shows effects of molecular oxygen in T1 and T2 in BSA solutions. In the comparison between bubbled and non-bubbled BSA solution, there was small reduction in T1 (13±1%, p>0.05) and T2 (1±2%, p>0.05) (Fig. 3 a–b). Representative T1 and T2 time maps obtained from BSA samples bubbled with an hour were showed in Fig. 3 c–d, respectively.

Figure 1.

T1 and T2 times of egg white treated with various concentrations of H2O2. Apparent reduction in T1 is seen in treaded egg white (a, b) while there is much less change in T2 (c,d).

Figure 2.

T1 and T2 times of 20 % BSA treated with various concentrations of H2O2. No distinct change in T1 is seen (a, b) and there is obvious reduction in T2 (c,d).

Figure 3.

Effects of molecular oxygen on relaxation times T1 and T2 in BSA solutions. Small or negligible changes are observed in both T1 (a) and T2 (b) due to oxygen introduced by bubbling in the sample up to an hour. (c) and (d) are representative T1 and T2 time maps of a control sample and a sample treated for an hour. In general, the effects from oxygen T1 and T2 are not significant (p>0.05).

The dynamic of T1 and its relative changes over time for the egg white sample (0.25 v/v% H2O2) are shown in Fig. 4a and b, respectively. The relative T1 changes were fitted with pseudo-first order reaction kinetics with high overall goodness-of-fit (R-square=83±6%). Based on the fitting, the produced ROS concentration over time were estimated (18.4±0.1 pM at 0.5 hour, 11.6±2.9 pM at 1 hour, 6.4±2.3 pM at 2 hour, 5.2±4 pM at 3 hour, and 3.24±0 pM at 4 hour) using Equation 2. The corresponding CNR are (10.0±0.0 at 0.5 hour, 7.0±1.9 at 1 hour, 3.9±1.2 at 2 hour, 1.5±0.8 at 3 hour, and 1.8±0.0 at 4 hour) (Fig. 4c). According to Rosen criteria, requiring CNR > 5, the detection sensitivity of ROS imaging was around 10 pM assuming a lifetime of 1 μs for the hydroxyl radicals.(8–13)

Figure 4.

Temporal change of T1 in egg white treated with 0.25 v/v% H2O2 (a). T1 is recovered back to the baseline after 4 hours. The relative changes of T1 measurements were fitted to a mono-exponential decay (b). The corresponding contrast-to-noise ratios are shown in (c).

With the estimated ROS concentrations over time and the corresponding T1 relaxation times, the T1 relaxivity of ROS was computed to be 3.4×107 s−1·mM−1, which is much larger than that of Gd-DTPA (0.9 s−1·mM−1) (Fig.5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of T1 relaxivity of ROS (a) with that of Gd-DTPA (b).

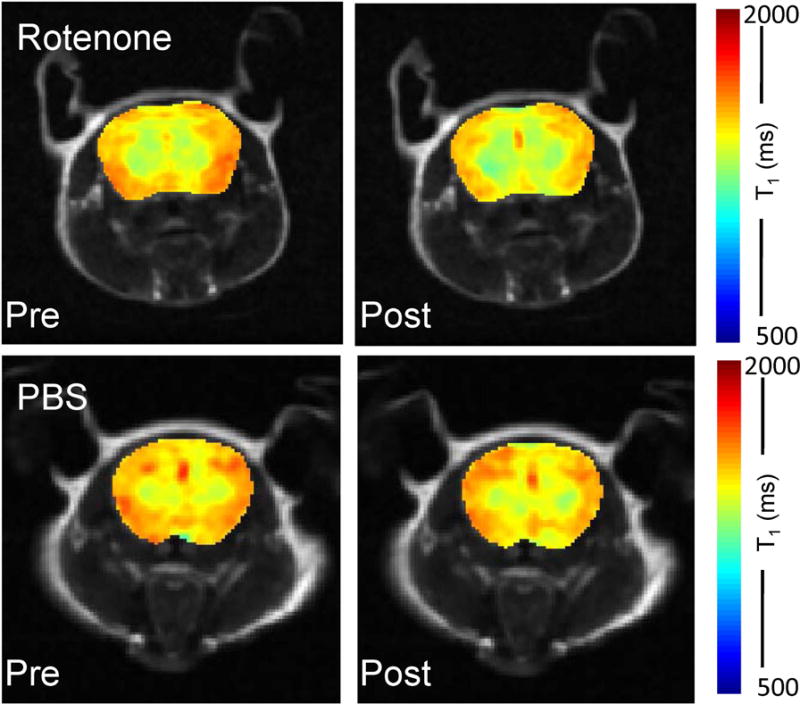

T1 maps for the detection of ROS production in vivo was demonstrated in rotenone treated mice. In vivo results were consistent with phantom studies by showing a significant reduction in brain T1 relaxation time due to rotenone compared to the baseline (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6). Representative T1 maps from a rotenone treated mice and a control are shown in Fig. 7. The relative reduction in T1 from cortex, thalamus, and whole brain are 7.0±1.7%, 6.4±1.6%, and 5.1±2.5%, respectively. In contrast, the T1 changes were not observed in control mice (~1.9±1.3 %).

Figure 6.

T1 values of mouse brains before and after rotenone (upper row) /PBS (lower row) treatment. There is significant reduction in T1 in cortex (a), thalamus (b) and whole brain (c) indicating overproduced ROS in mice with rotenone treatment. In contrast, the change in T1 in PBS-treated mice is trivial (lower row).

Figure 7.

Representative T1 maps of mouse brains (color-overlaid over anatomical images) before and after rotenone (upper row) /PBS (lower row) treatment. Observable changes in T1 are only shown from rotenone treated mice.

Discussion

Non-invasive high-resolution ROS imaging based on endogenous contrasts is highly demanding. The paramagnetic effect of ROS (with unpaired electrons) has been recently reported.(28,29) Those studies focusing on degenerative retina diseases show evidence that T1 time in the retinal pigment epithelium layer was reduced in manganese-superoxide-dismutase (MnSOD) knockout (KO) mice compared to healthy controls.(29) Note that MnSOD is a primary antioxidant enzyme in mitochondria. Moreover, T1 time recovered in KO mice after antioxidant treatments, indicating that free radicals were responsible for T1 shortening. Although the link between paramagnetic effects and free radicals has been suggested in these studies, for the first time, we quantitatively characterized the T1 relaxivity of ROS and the detection sensitivity of ROS MRI based on its endogenous paramagnetic effect.

Free radical ROS has an extremely short lifetime, typically in μs.(8–13) Instead of developing an MRI technique with sub microsecond temporal resolution to study its MRI properties, we alternatively established an imaging platform that sustainably produces ROS. Fresh egg white treated with H2O2 prolongs ROS production for hours with quantifiable ROS concentrations over time. Note that in Fenton reactions, a variety of ROS may be produced including OH and HOO.. Those radicals are convertible through complicated redox reactions and pathways. On average, one H2O2 produces one .OH as indicated in Fenton reactions.

It has been reported that ROS concentration over time in H2O2 involved reactions follows first order or pseudo-first order kinetics.(22,30) Our dynamic T1 reduction data also reflected such kinetics consistently. Based on this simple model, we estimated the detection sensitivity of ROS MRI is at the pM level under the assumption of 1 μs lifetime for hydroxyl radicals.(8–13) Under shorter lifetimes (e.g. 1 ns), the detection sensitivity will be proportionally higher (e.g. 10−3 pM level). Given that the physiological concentrations of ROS is in the μM level (14) and their concentration can be elevated by over 100 times under conditions such as inflammation or stroke and reperfusion, (14,31,32) the pM detection sensitivity provides us the capability to detect ROS under both physiological and pathological conditions.

By curve fitting time resolved ROS concentration estimates, we were able to quantify the relaxivity of free radicals, which was much larger than Gd-DTPA in egg white tissues. Such high relaxivity is presumably due to ROS’ unpaired electrons and their extremely high reactivity.

In terms of specificity, the observed T1-shortening effect observed in H2O2 treated egg white may be contributed by other confounding factors such as H2O2 itself, molecular oxygen, and oxidized proteins. We found that the effects from these factors were small. First of all, the influence of H2O2 itself on relaxation time T1 was negligible, as less than 2% of T1 reduction was observed in H2O2 doped BSA solutions, that produced no ROS. However, there was significant reduction in T2 relaxation time from H2O2 treatment that is consistent to reported studies.(27) For molecular oxygen, given that the observed T1 reduction in our BSA solution was small (~10%), its contribution to the observed T1 reduction in H2O2-treated egg white studies was limited. Third, H2O2 treatment might oxidize proteins in egg white and lead to possible reduction in relaxation properties. However, it has been shown that the significant coagulation, gelation, modification, or denaturation of egg white protein occurs when H2O2 treatment concentration exceeds 1 v/v% (33), which is far beyond from the concentrations used in this study. The fact that T1 time in H2O2-treated egg white samples recovered back towards the baseline level at 4 hours after treatment indicated that the contribution from irreversible protein oxidation was also negligible. Given these considerations, we concluded that the T1 changes observed in the egg white experiments are predominantly due to ROS.

The feasibility of in vivo detection was demonstrated in the healthy mice with and without rotenone treatment. Our study showed consistent changes in T1 in a similar way as what we observed in the phantom studies. Meanwhile, there was no obvious change in T1 in PBS treated mice. All these indicate that the elevation in steady-state ROS concentration due to rotenone treatment is detectable with endogenous ROS MRI based on T1 contrast. Given that rotenone was used to produce Parkinson’s diseases (PD) in preclinical models (24,25), ROS MRI may provide more insights of the role of ROS in the pathogenesis of PD in the future studies.

T1 relaxation time can be affected by many factors, including dipole-dipole interactions, chemical shift anisotropy, molecular translation (such as flow and diffusion), chemical exchange, and scalar (J-coupling) and electric-quadrupole coupling (34–37). Absolute quantification of ROS based on T1 weighted MRI contrast will be challenging. This technique may be more suitable to detect or to quantify the relative changes in radical production compared to control groups in vivo under acute and chronic conditions while other factors are relatively controlled.

Another limitation is that we did not compare our estimation of ROS contents to an established measurement. However, it is worthwhile to note that there is currently no reference standard for the absolute quantification of ROS because biochemical analysis and exogenous contrast-based imaging methods inherently alter ROS concentrations in tissues under study through the addition of probes or contrast agents.

Nevertheless, we have characterized the sensitivity of ROS detection using MRI T1 weighted contrast and their T1 relaxivity. In vivo detection of ROS with endogenous T1 contrast MRI has also been demonstrated. These initial results are potentially important for clinical translations of the endogenous MRI of short-lived ROS.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dr. Frederick C. Damen from the Radiology Department at the University of Illinois at Chicago who helped with comments and criticism by reading the manuscript.

Grant support: This study was supported by NIH grant R21 EB023516.

References

- 1.Cahill-Smith S, Li JM. Oxidative stress, redox signalling and endothelial dysfunction in ageing-related neurodegenerative diseases: a role of NADPH oxidase 2. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(3):441–453. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Bush AI. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(3):205–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97(6):1634–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray PD, Huang B-W, Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24(5):981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acharya A, Das I, Chandhok D, Saha T. Redox regulation in cancer: A double-edged sword with therapeutic potential. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3(1):23–34. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.1.10095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li N, Ragheb K, Lawler G, et al. Mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone induces apoptosis through enhancing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):8516–8525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pryor WA. Oxy-radicals and related species: their formation, lifetimes, and reactions. Annu Rev Physiol. 1986;48:657–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitt FJ, Renger G, Friedrich T, et al. Reactive oxygen species: re-evaluation of generation, monitoring and role in stress-signaling in phototrophic organisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1837(6):835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalyanaraman B. Teaching the basics of redox biology to medical and graduate students: Oxidants, antioxidants and disease mechanisms. Redox Biol. 2013;1(1):244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabrese AN, Ault JR, Radford SE, Ashcroft AE. Using hydroxyl radical footprinting to explore the free energy landscape of protein folding. Methods. 2015;89:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan Y, Chen G, Wei H, et al. Fast photochemical oxidation of proteins (FPOP) maps the epitope of EGFR binding to adnectin. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014;25(12):2084–2092. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0993-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van de Meerakker SYT, Vanhaecke N, van der Loo MPJ, Groenenboom GC, Meijer G. Direct Measurement of the Radiative Lifetime of Vibrationally Excited OH Radicals. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95(1):013003. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attri P, Kim YH, Park DH, et al. Generation mechanism of hydroxyl radical species and its lifetime prediction during the plasma-initiated ultraviolet (UV) photolysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9332. doi: 10.1038/srep09332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grill HP, Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P, Weisfeldt ML, Flaherty JT. Direct measurement of myocardial free radical generation in an in vivo model: Effects of postischemic reperfusion and treatment with human recombinant superoxide dismutase. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20(7):1604–1611. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu HN, Nioka S, Glickson JD, Chance B, Li LZ. Quantitative mitochondrial redox imaging of breast cancer metastatic potential. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(3) doi: 10.1117/1.3431714. 036010-036010-036010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarracanie M, Armstrong BD, Stockmann J, Rosen MS. High speed 3D overhauser-enhanced MRI using combined b-SSFP and compressed sensing. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(2):735–745. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lurie DJ, Li H, Petryakov S, Zweier JL. Development of a PEDRI free-radical imager using a 0.38 T clinical MRI system. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(1):181–186. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emoto MC, Yamato M, Sato-Akaba H, Yamada K, Matsuoka Y, Fujii HG. Brain imaging in methamphetamine-treated mice using a nitroxide contrast agent for EPR imaging of the redox status and a gadolinium contrast agent for MRI observation of blood–brain barrier function. Free Radic Res. 2015;49(8):1038–1047. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2015.1040787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsitovich PB, Burns PJ, McKay AM, Morrow JR. Redox-activated MRI contrast agents based on lanthanide and transition metal ions. J Inorg Biochem. 2014;133(0):143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratnakar SJ, Viswanathan S, Kovacs Z, Jindal AK, Green KN, Sherry AD. Europium(III) DOTA-tetraamide Complexes as Redox-Active MRI Sensors. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(13):5798–5800. doi: 10.1021/ja211601k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratnakar SJ, Soesbe TC, Lumata LL, et al. Modulation of CEST Images in Vivo by T1 Relaxation: A New Approach in the Design of Responsive PARACEST Agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(40):14904–14907. doi: 10.1021/ja406738y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin S-S, Gurol MD. Catalytic Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide on Iron Oxide: Kinetics, Mechanism, and Implications. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32(10):1417–1423. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickerscheid D, Lavalaye J, Romijn L, Habraken J. Contrast-noise-ratio (CNR) analysis and optimisation of breast-specific gamma imaging (BSGI) acquisition protocols. EJNMMI Research. 2013;3:21–21. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cannon JR, Tapias V, Na HM, Honick AS, Drolet RE, Greenamyre JT. A highly reproducible rotenone model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34(2):279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan-Montojo F, Anichtchik O, Dening Y, et al. Progression of Parkinson’s Disease Pathology Is Reproduced by Intragastric Administration of Rotenone in Mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1):e8762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colin Cameron A, Windmeijer FAG. An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models. J Econometrics. 1997;77(2):329–342. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buljubasich L, Blümich B, Stapf S. Reaction monitoring of hydrogen peroxide decomposition by NMR relaxometry. Chemical Engineering Science. 2010;65(4):1394–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajca A, Wang Y, Boska M, et al. Organic radical contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(38):15724–15727. doi: 10.1021/ja3079829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkowitz BA, Lewin AS, Biswal MR, Bredell BX, Davis C, Roberts R. MRI of Retinal Free Radical Production With Laminar Resolution In Vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(2):577–585. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krumova K, Cosa G. Overview of Reactive Oxygen Species. Singlet Oxygen: Applications in Biosciences and Nanosciences Volume 1: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2016:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, Reddy SP, Malik AB. Reactive Oxygen Species in Inflammation and Tissue Injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;20(7):1126–1167. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunther MR, Sampath V, Caughey WS. Potential roles of myoglobin autoxidation in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(11–12):1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snider DW, Cotterill OJ. Hydrogen peroxide oxidation and coagulation of egg white. J Food Sci. 1972;37(4):558–561. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bloembergen N, Purcell EM, Pound RV. Relaxation Effects in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Absorption. Phys Rev. 1948;73(7):679–712. [Google Scholar]

- 35.EL H. Spin echoes. Phys Rev. 1950;80(4):15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr HY, Purcell EM. Effects of Diffusion on Free Precession in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Experiments. Phys Rev. 1954;94(3):630–638. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torrey HC. Bloch Equations with Diffusion Terms. Phys Rev. 1956;104(3):563–565. [Google Scholar]