Abstract

Administration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has emerged as a potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of myocardial infarction (MI). However, the increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) in ischemic cardiac tissue compromises the survival of transplanted MSCs, thus resulting in limited therapeutic efficiency. Therefore, strategies that attenuate oxidative stress-induced damage and enhance MSC viability are required. Geraniin has been reported to possess potent antioxidative activity and exert protective effects on numerous cell types under certain conditions. Therefore, geraniin may be considered a potential drug used to modulate MSC-based therapy for MI. In the present study, MSCs were pretreated with geraniin for 24 h and were exposed to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 4 h. Cell apoptosis, intracellular ROS levels and mitochondrial membrane potential were measured using Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate/ propidium iodide staining, the 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate fluorescent probe and the membrane permeable dye JC-1, respectively. Glutathione and malondialdehyde levels were also investigated. The expression levels of apoptosis-associated proteins and proteins of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway were analyzed by western blotting. The results demonstrated that geraniin could significantly attenuate H2O2-induced cell damage by promoting MSC survival, reducing cellular ROS production and maintaining mitochondrial function. Furthermore, geraniin modulated the expression levels of phosphorylated-Akt in a time- and dose-dependent manner. The cytoprotective effects of geraniin were suppressed by LY294002, a specific PI3K inhibitor. In conclusion, the present study revealed that geraniin protects MSCs from H2O2-induced oxidative stress injury via the PI3K/Akt pathway. These findings indicated that cotreatment of MSCs with geraniin may optimize therapeutic efficacy for the clinical treatment of MI.

Keywords: geraniin, mesenchymal stem cells, hydrogen peroxide, oxidative stress, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathway

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is among the main causes of mortality worldwide (1). Irreversible loss of cardiac myocytes and concomitant cicatrization are induced by MI; therefore, patients exhibit poor cardiac pump function and congestive heart failure. Cell-based therapy for MI represents an emerging strategy in biological therapeutics (2,3). As one of the most frequently investigated cellular populations, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are particularly attractive therapeutic candidates. MSC-based therapy relies on the self-renewal capability of MSCs, and the ability of MSCs to differentiate into cardiovascular cells and secrete multitudinous bioactive molecules. These actions subsequently activate endogenous neovascularization, immunomodulation and cardiac regeneration, thus resulting in restoration of cardiac function (4). However, current evidence indicates that poor viability of engrafted MSCs in the infarcted myocardium is a primary limitation of the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs (5,6). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide radicals and hydroxyl radicals, are produced during infarction (7) or reperfusion of ischemic hearts (8). ROS may lead to impaired cell metabolism and decreased cell viability, thus inhibiting transplanted MSCs from taking effect. Therefore, protecting MSCs from apoptosis, together with enhancing their ability to survive under oxidative stress, is crucial for optimizing MSC-based therapy.

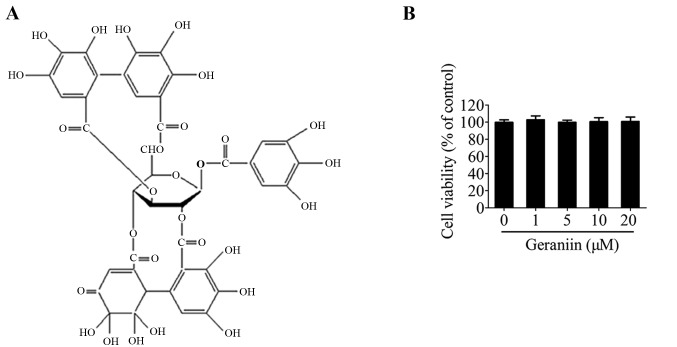

Polyphenols, or polyphenolic compounds, are widely distributed in natural plants, and range from simple structures, such as flavonoids, to highly complex polymeric substances, including proanthocyanidins and ellagitannins (9). Due to their various biological activities, polyphenols exhibit potential as effective therapeutic drugs. In addition, they have been demonstrated to display numerous pharmacological activities, including anticarcinogenic (10), antibacterial (11) and antidiabetic (12) effects. Furthermore, polyphenols are strong antioxidants, due to their free radical-scavenging activities (13). Geraniin is a typical ellagitannin, which has been identified as the major active compound extracted from Geranium sibiricum. A previous study reported that geraniin possesses marked nitric oxide-scavenging, superoxide radical-scavenging and β-carotene-linoleic acid-bleaching properties due to its unique chemical structure (Fig. 1A) (14). Furthermore, geraniin has been confirmed to protect liver cells against ethanol-induced cytotoxicity (15) and inhibit apoptosis of pulmonary fibroblasts under γ-radiation conditions (16). Our previous study demonstrated that geraniin may exert strong ROS-scavenging activities when preventing THP-1 macrophages from switching to an M1 phenotype under lipopolysaccharide stimulation (17). Since H2O2 is often used in vitro to simulate the oxidative stress microenvironment detected in ischemic heart tissue, the present study hypothesized that geraniin may defend MSCs against H2O2-induced damage. The present study aimed to investigate the cytoprotective effects of geraniin on MSCs against H2O2-induced cellular injury, as well as the underlying mechanism.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of geraniin and effects of geraniin on MSC viability. (A) Chemical structure of geraniin. (B) MSCs were treated with various concentrations of geraniin for 24 h, and viability was measured using the Cell Counting kit-8 assay. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from five replicate wells and are representative of three independent experiments. MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Geraniin (purity ≥98%) was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −80°C. The stock concentration of geraniin was 10 mM. DMSO and H2O2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The conjugated antibodies used to identify MSCs: Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-CD29 (555005) and anti-CD44 (561859), and phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD45 (553091) and anti-CD90 (551401), as well as the Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis detection kit, were all purchased from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8) was from Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. (Kumamoto, Japan). Hoechst 33342, JC-1 dye, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescent probe, glutathione (GSH) kit (S0053), malondialdehyde (MDA) kit (S0131), ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), cell mitochondrial protein isolation kit (C3601), radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer, bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit and mouse polyclonal anti-β-actin (AA128) were all purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Rabbit antibodies against phosphorylated-protein kinase B [p-Akt (Ser473); 4060s], Akt (9272s), caspase-3 (9662s), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2; 2876s), Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax; 2772s) and cytochrome c (Cyt C; 4272s), and LY294002 [phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) specific inhibitor], were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit (ZB-2301) and anti-mouse (ZB-2305) secondary antibodies were obtained from OriGene Technologies, Inc., (Beijing, China).

MSCs isolation and culture

MSCs were isolated and harvested from male Sprague-Dawley rats (age, 3 weeks old; weight, 60–80 g), as previously described with minor modifications (18). A total of 10 SPF Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Science Department of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (Harbin, China). They were kept under standard animal housing conditions (temperature, 21±1°C; humidity, 55±5%), at a 12-h dark/light cycle and had access to unlimited food and water. The present study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee on Animal Care and Use of Harbin Medical University. Briefly, total bone marrow was flushed from the tibias and femurs of the rats with 10 ml DMEM/F12 using a sterile syringe. After centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min, the remaining pellets were resuspended in 5 ml DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and were then seeded into cell culture flasks at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Following incubation for 48 h, the culture medium and non-adherent cells were discarded and fresh medium was added. The medium was replaced every 72 h thereafter. Cells were cultured until they reached 80% confluence, after which they were passaged. Cells were split using 0.25% trypsin and were expanded at a 1:2 or 1:3 dilution. Cells from passages 3–5 were used in the subsequent experiments. The MSC population was characterized according to positive (CD44, CD29 and CD90) and negative (CD45) cell surface markers by flow cytometry, as reported in our previous studies (18,19).

Cell treatments

All treatments were conducted at 37°C in the incubator. MSCs were seeded into six-well plates or a 25 cm2 culture flask. Once cell density reached 60–70%, H2O2 (100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 µM), mixed with serum-free DMEM/ F12 for 4 h, was used to establish an in vitro oxidative stress model. Geraniin, at 1, 5, 10 and 20 µM, was separately preincubated in DMEM/F12 for 24 h. The inhibitor of PI3K, LY294002 (25 µM), or the ROS scavenger, NAC (500 µM), was added 1 h prior to H2O2 treatment without geraniin co-treatment. Cells cultured in complete medium without any specific treatment comprised the control group.

Cell viability assay

MSC viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. Briefly, cells were plated into 96-well plates (3×103 cells/well). Following cell adhesion to the plates, appropriate treatments were administered. Subsequently, the medium was removed and replaced with 100 µl fresh DMEM/F12 and 10 µl CCK-8 solution in each well. The plates were maintained at 37°C for 1 h. Finally, absorbance was detected at 450 nm using a Tecan Infinite 200 PRO microplate reader (Tecan Austria GmbH, Grödig, Austria).

Measurement of cell apoptosis

Apoptosis of MSCs was determined using the Annexin V-FITC/PI staining method. Following treatment, the cells were harvested, washed with ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 400 µl binding buffer. The cell suspension was then incubated with 5 µl Annexin V solution for 15 min at room temperature in the dark, followed by incubation with 5 µl PI for an additional 5 min. The cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry using BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences). Approximately 1×105 cells were detected in each sample. According to the reaction principles, Annexin V−/PI− staining signified viable cells, Annexin V+/PI− indicated early apoptotic cells, and Annexin V+/PI+ represented late apoptotic or necrotic cells.

Assessment of morphological alterations

MSCs were treated with geraniin and H2O2 in six-well plates. Hoechst 33342 was used to detect cell nuclear condensation and fragmentation. After fixing in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, cells were washed twice with PBS, stained with 5 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 5 min and washed a further two times with PBS. Finally, cells were assessed by fluorescence microscopy. Apoptotic cells were identified by condensed or fragmented nuclei.

ROS, GSH and MDA assays

Intracellular ROS levels were determined using a ROS assay kit. Briefly, cells were incubated with the diluted fluorescent probe, DCFH-DA, for 20 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed three times with serum-free DMEM/F12, collected and analyzed using a flow cytometer. Due to the important roles of GSH and MDA in ROS-associated oxidative stress, their concentrations were also measured using commercial kits according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm)

JC-1 was used to measure alterations in Ψm. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS, stained with 5 µM JC-1 and maintained for 20 min at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were washed twice with ice-cold JC-1 staining buffer and were then directly observed under a fluorescence microscope, or were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, lysed with RIPA lysis buffer and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The extraction of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial proteins was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. BCA protein assay was used to quantify protein concentrations. Equal amounts of total protein (50 µg/ lane) were separated by 8–12% SDS-PAGE and were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk diluted in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) at 37°C for 1 h, and were then incubated with diluted primary antibodies against p-Akt (S473) (1:1,000), total-Akt (1:1,000), cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000), Bax (1:1,000), Bcl-2 (1:1,000), Cyt C (1:1,000) and β-actin (1:800) overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with TBST, membranes were incubated with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000) for 1 h at room temperature. The images of the immune complexes were developed by ECL in the dark, and images were captured using a Tanon-5200 (Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Band density was determined using ImageJ (1.48u; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of geraniin on MSC viability

Initially, the effects of geraniin on MSC viability were examined using the CCK-8 assay. Treatment with geraniin for 24 h had little influence on cell viability compared with the 0 µM geraniin group (Fig. 1B). This result indicated that geraniin did not exert toxic effects on MSCs.

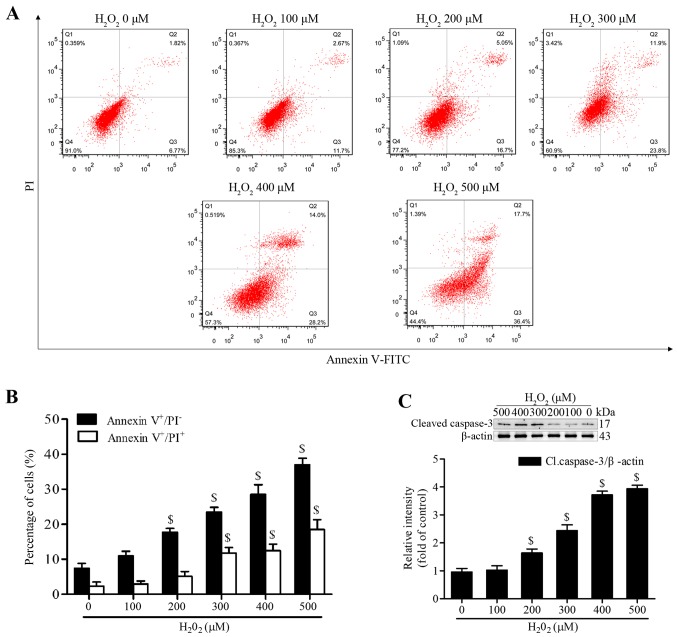

Geraniin significantly inhibits H2O2-induced apoptosis of MSCs

H2O2 has been reported to induce apoptosis of MSCs at various concentrations and time-points (20,21). To establish a successful in vitro oxidative stress model, the present study investigated the proapoptotic effects of H2O2 on MSCs. Following treatment with various concentrations of H2O2 (100–500 µM) in serum-free medium for 4 h, MSCs were stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI. The proportion of early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI−) was significantly increased following treatment with ≥200 µM H2O2, whereas the proportion of late apoptotic or necrotic MSCs (Annexin V+/PI+) was markedly increased following treatment with ≥300 µM (Fig. 2A and B). In addition, the expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 were significantly increased at 200 µM and continued to increase to 500 µM (Fig. 2C). We then selected treatment with H2O2 at 300 µM for 4 h as the condition to induce effective apoptosis, since this concentration generated moderate apoptotic cells.

Figure 2.

H2O2 induces apoptosis of MSCs. (A and B) Cells were treated with a range of H2O2 concentrations for 4 h, and apoptosis was analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining assay. (C) H2O2-induced cleaved caspase-3 expression was measured by western blotting, β-actin was used for normalization. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent measurements. $P<0.05 compared with the 0 µM H2O2 group. Cl.caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; PI, propidium iodide.

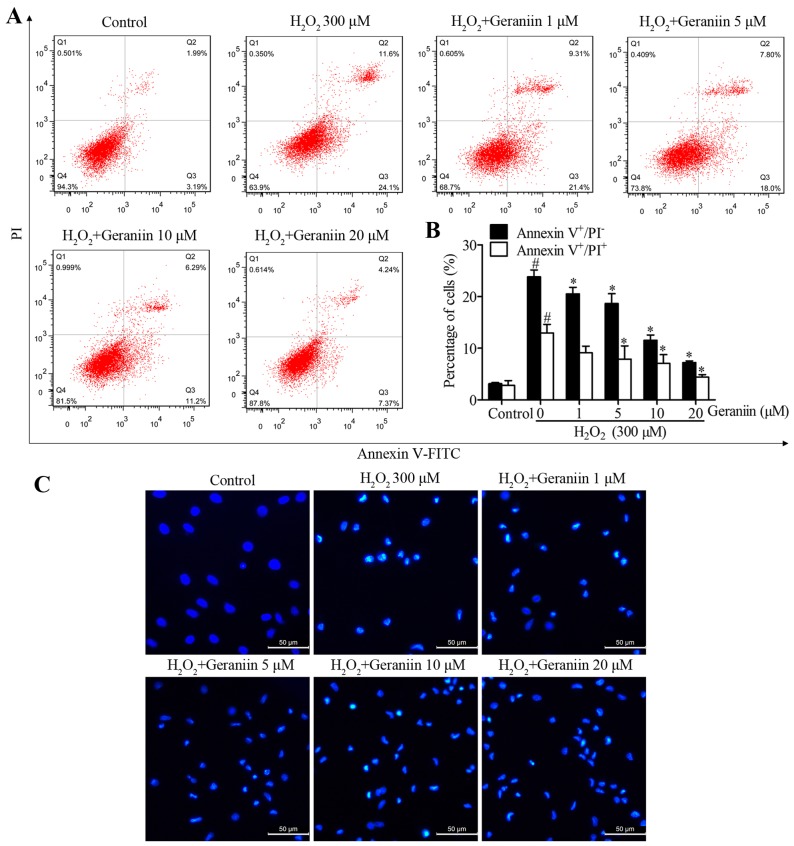

To determine whether geraniin rescues MSCs from H2O2-induced apoptosis, MSCs were pretreated with increasing concentrations of geraniin (1, 5, 10 and 20 µM) for 24 h. MSCs were then co-treated with geraniin and H2O2. A significant reversal in the percentage of H2O2-induced Annexin V+/PI− cells, in response to geraniin, was observed by flow cytometry (geraniin 1 µM, 20.53±1.25%; 5 µM, 18.67±1.89%; 10 µM, 11.57±1.01%; 20 µM, 7.23±0.31%; P<0.05 vs. H2O2, 23.83±1.32%) (Fig. 3A and B). However, 1 µM geraniin had no effect on the proportion of Annexin V+/PI+ cells, whereas the other concentrations significantly reduced the percentage of late apoptotic or necrotic cells (geraniin 5 µM, 7.88±2.58%; 10 µM, 7.05±1.72%; 20 µM, 4.40±0.48%; P<0.05 vs. H2O2, 12.97±1.65%) (Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, in apoptotic cells, nuclei become condensed or fragmented, whereas in normal cells, nuclei are circular or oval. Hoechst 33342 staining was used to confirm the presence of nuclear morphological alterations. Cells treated with H2O2 appeared to possess shrunken and fragmented nuclei; however, those pretreated with geraniin exhibited marked amelioration of H2O2-induced nuclear impairment. These data indicated that geraniin may effectively attenuate H2O2-induced MSC apoptosis (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Geraniin reduces H2O2-induced MSC apoptosis. MSCs were treated with increasing concentrations of geraniin for 24 h and were then exposed to 300 µM H2O2 for 4 h. Apoptosis was reduced by geraniin in a dose-dependent manner, as identified by (A and B) flow cytometry and (C) Hoechst 33342 staining (original magnification, 200×; scale bar, 50 µm). #P<0.05 compared with the control group; *P<0.05 compared with the 300 µM H2O2 group. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells PI, propidium iodide.

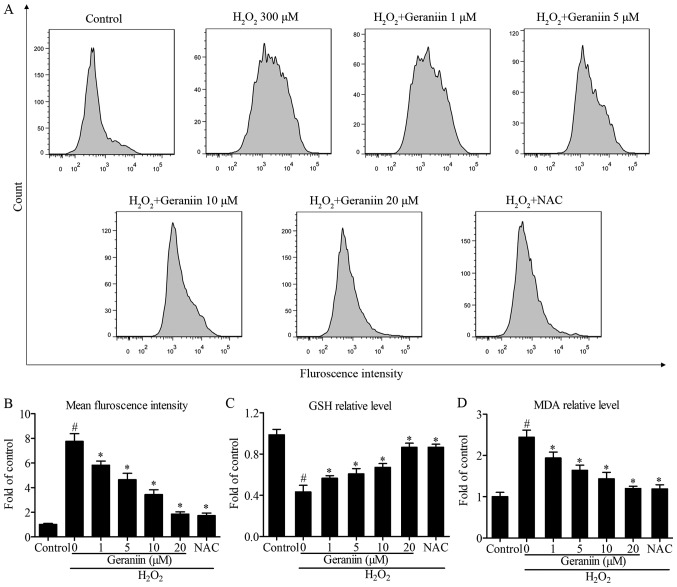

Geraniin exerts protective effects by regulating ROS genera- tion

Since ROS serves a pivotal role in proapoptotic signaling cascades (22), the present study examined the effects of geraniin on ROS generation using flow cytometry. The results demonstrated that H2O2 induced a 7.6-fold increase in ROS production compared with the control group. However, pretreatment with geraniin markedly suppressed ROS generation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4A and B). Following treatment with NAC, a general ROS scavenger, similar results were recorded compared with 20 µM geraniin (mean fluorescence intensity: Geraniin 20 µM, 476.33±46.65; NAC, 443.80±53.15, P>0.05) (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, alterations in intracellular GSH and MDA contents were investigated; cells pretreated with geraniin had significantly increased GSH levels, whereas MDA production was suppressed by geraniin (Fig. 4C and D). These findings indicated that geraniin is able to enhance the cellular antioxidant system and remove redundant ROS.

Figure 4.

Geraniin exerts protective effects by regulating ROS generation. MSCs were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of geraniin for 24 h or NAC for 1 h, followed by exposure to H2O2 for 4 h. (A) Intracellular ROS levels were evaluated by flow cytometry and (B) data were quantified. Alterations in (C) GSH and (D) MDA levels were measured. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. #P<0.05 compared with the control group; *P<0.05 compared with the H2O2-treated group. GSH, glutathione; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MDA, malondialdehyde; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; NAC, N-acetyl-L-cysteine; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

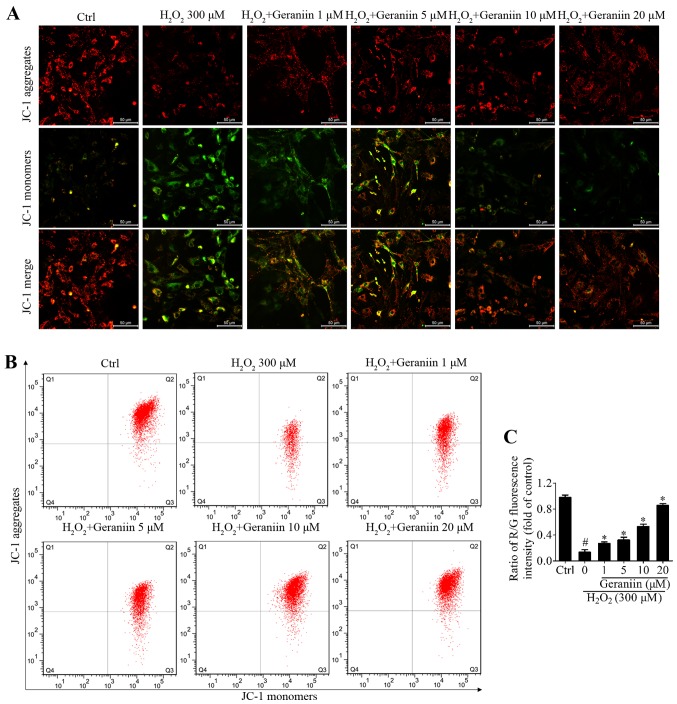

Geraniin protects MSCs against oxidative stress through stabilizing the Ψm

Mitochondria in eukaryotic cells are the primary components of respiration, and are critical in the defense against oxidative stress-induced damage (23). Maintaining the Ψm is essential to ensure the scavenging efficiency of ROS, and to prevent cell apoptosis or other stress-associated events induced by excessive ROS (24). JC-1 is a Ψm-sensitive dye, which aggregates in the mitochondrial matrix and exhibits red fluorescence in normal cells. However, when the Ψm is reduced, JC-1 is converted to its monomer state, which exhibits green fluorescence. H2O2 resulted in a marked reduction in Ψm within MSCs, whereas geraniin markedly upregulated the Ψm, as identified by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5A). In addition, the ratio of red/green fluorescence intensity was significantly downregulated under H2O2 exposure compared with in the control group; however, this effect was reversed by geraniin in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5B and C). These findings suggested that geraniin may exert beneficial effects on mitochondrial function.

Figure 5.

Geraniin protects MSCs against oxidative stress through stabilizing the Ψm. MSCs were treated with the indicated concentrations of geraniin for 24 h, followed by H2O2 administration for 4 h. Alterations in Ψm were analyzed by (A) fluorescence microscopy (original magnification, ×200; scale bar, 50 µm) and (B) flow cytometry using the JC-1 staining method. (C) Ratio of R/G fluorescence intensity was quantified. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three separate experiments. #P<0.05 compared with the control group; *P<0.05 compared with the H2O2-treated group. Ψm, mitochondrial membrane potential; Ctrl, control; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; R/G, red/green.

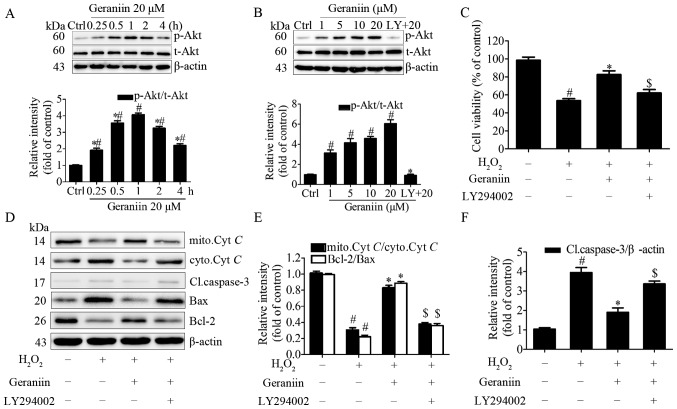

PI3K/Akt signaling is required for geraniin to exert anti-apoptotic effects on MSCs

It has previously been reported that geraniin exerts cytoprotective effects on HepG2 cells via activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and PI3K/Akt pathways (25). Due to the importance of the PI3K/Akt pathway on classical survival signals (26), the present study aimed to determine the association between geraniin and the PI3K/Akt pathway in MSCs. Cells were treated with geraniin (20 µM) for the indicated periods of time; the protein expression levels of p-Akt (Ser473) were transiently upregulated at 15 min and peaked at 60 min, prior to subsequent downregulation (Fig. 6A). In addition, the effects of 1 h treatment with various concentrations of geraniin on p-Akt (Ser473) expression in MSCs was investigated; p-Akt expression was upregulated in a dose-dependent manner. Conversely, p-Akt expression was markedly inhibited following pretreatment with LY294002, a PI3K-specific inhibitor (Fig. 6B). These findings indicated that geraniin may activate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in a time- and dose-dependent manner.

Figure 6.

PI3K/Akt signaling is involved in the anti-apoptotic effects of geraniin on MSCs. (A) Cells were treated with geraniin (20 µM) for the indicated time-periods or (B) with the indicated concentrations of geraniin for 1 h. The expression levels of p-Akt were evaluated by western blotting. (C) Cells were pretreated with LY294002, and were then incubated with geraniin and H2O2; cell viability was measured using the Cell Counting kit-8 assay. Expression levels of proteins associated with the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway were assessed (D) by western blotting and (E and F) data were semi-quantified. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. #P<0.05 compared with the control group; *P<0.05 compared with the group treated with 20 µM geraniin for 1 h (A and B); *P<0.05 compared with the H2O2 group (C-F); $P<0.05 compared with the geraniin + H2O2 group. Akt, protein kinase B; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; Cl.caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3; ctrl, control; cyto.Cyt C, cytoplasmic cytochrome c; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; LY, LY294002; mito.Cyt C, mitochondrial cytochrome c; p-, phosphorylated; t-, total.

To gain further insight into the role of the PI3K/Akt pathway in the protective effects of geraniin on MSCs, cells were preconditioned with LY294002 and were then exposed to 20 µM geraniin and H2O2. PI3K inhibition significantly attenuated the anti-apoptotic effects of geraniin on MSCs under H2O2 treatment, as evidenced by a decrease in cell survival rate using CCK-8 assay (Fig. 6C). Since reductions in the Ψm and increased cleaved caspase-3 expression are initiating and amplifying factors of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, it may be suggested that H2O2 induces apoptosis of MSCs through regulating the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Therefore, the expression levels of Cyt C, cleaved caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2 were investigated. Treatment with geraniin induced a marked increase in the expression levels of mitochondrial Cyt C and Bcl-2, and a decrease in the expression levels of cytoplasmic Cyt C, cleaved caspase-3 and Bax (Fig. 6D–F). These effects were reversed by LY294002. These data indicated that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway may contribute to the prosurvival role of geraniin in MSCs under H2O2 treatment.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that geraniin could attenuate H2O2-induced cell damage through promoting MSC survival, reducing cellular ROS production and maintaining mitochondrial function. Furthermore, the effects of geraniin were mediated by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Conversely, inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway weakened the protective effects of geraniin. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to report the cytoprotective effects of geraniin on MSCs and reveal the underlying mechanism.

MSCs are easily isolated and expanded, and can be transplanted in the heart; therefore, they are considered leading candidates for cellular therapy (27). Substantial data from preclinical and clinical studies support the cardioprotective effects of MSCs. Amado et al demonstrated that, following MSC implantation into swine, reappearance of myocardial tissue and restoration of cardiac contractility could be detected using serial computed tomography imaging (28). Furthermore, the POSEIDON randomized trial demonstrated that intravenous administration of allogeneic MSCs within 7 days of acute MI markedly attenuated cardiac hypertrophy, reduced ventricular arrhythmia, improved heart function and decreased rehospitalization for cardiac complications (27). However, the practical applications of MSCs are restricted by their poor survival rate. A previous study indicated that after 4 days, only 0.44% of engrafted MSCs survived and resided in the myocardium (29). This low survival rate is mainly due to the hostile microenvironment in injured heart tissue, and ROS burst in the infarcted region is the major risk factor (30). As one of the most stable ROS, H2O2 is often used to establish an in vitro oxidative stress model for studies regarding apoptosis-associated mechanisms (31). In the present study, treatment with 300 µM H2O2 for 4 h markedly increased apoptosis of MSCs, thus indicating that exogenous ROS burst results in the critical inducement of transplanted MSC apoptosis. In addition, this result reflects the necessity to identify novel methods to enhance MSC survival upon oxidative stress injury.

Pharmacological studies have confirmed that polyphenols are efficacious in treating ischemic heart diseases. Polyphenols extracted from grapes and wine have been reported to increase coronary flow in vivo (32). Epigallocatechin gallate, which is the major polyphenolic compound in green tea, has been revealed to prevent oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vitro (33). In addition, emerging evidence demonstrated that the mechanism of action of polyphenols is predominantly ascribed to their strong free radical-scavenging activity. Polyphenols are rich in hydroxyl groups, which can capture free radicals and inactivate ROS (34). There are numerous hydroxyl groups within geraniin, indicating its strong antioxidant activity. Therefore, the present study detected the antioxidative effects of geraniin on MSCs exposed to H2O2; the results confirmed that geraniin pretreatment may reduce excessive cellular ROS levels and preserve mitochondrial function, which may contribute to inhibiting H2O2-induced apoptosis. Furthermore, cells can defend themselves against oxidative stress through specific scavenging mechanisms, in which GSH and MDA are vital participants. GSH is an important intracellular antioxidative mediator that interacts with redundant ROS and balances cellular oxidation status. MDA is the end product of cellular lipid peroxidation in response to ROS damage. The severity of oxidative injury is, to some degree, reflected by cellular GSH and MDA levels. In the present study, geraniin was able to restore GSH levels, and decrease the amount of MDA, thus suggesting that geraniin functions through enhancing the intrinsic antioxidant repair system to inhibit ROS production and prevent accumulation of intracellular oxidative damage. Furthermore, reduced Ψm indicates severe mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction and increased generation of ROS, which enhances oxidative stress and activates caspase family-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis (35). The present study indicated that geraniin treatment increases Bcl-2 expression, and decreases the expression levels of Bax and cleaved caspase-3, thus suggesting that geraniin may act on Ψm stabilization. In addition, in normal cells, Cyt C is located in the mitochondrial inner membrane and works as an electron transmitter. Numerous proapoptotic stimuli, including ROS, increase permeability of the outer membrane and promote mobilization of Cyt C from the mitochondria to the cytosol. In the cytosol, Cyt C mediates maturation of the caspase family, including caspase-3, which ultimately induce cell death (36). In the present study, geraniin treatment inhibited the release of Cyt C from the mitochondria to the cytosol, which indirectly indicated that geraniin preserved mitochondrial membrane integrity. Taken together, these results revealed that geraniin improved MSC viability under oxidative stress by enhancing the ability of the antioxidant defense system to remove excessive ROS, maintaining mitochondrial function and inhibiting the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

The PI3K/Akt pathway has been reported to serve an important role in the biological behavior of MSCs in vitro and in MSC engraftment for ischemic treatment in vivo. A previous study confirmed that cell survival, proliferation and migration were enhanced when the PI3K/Akt pathway was activated in MSCs (21). In addition, transplantation of MSCs overexpressing Akt preserved normal cardiac metabolism and pH post-MI (37). In the present study, the results verified that geraniin could activate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, whereas PI3K inhibition abolished the effects of geraniin on MSCs. However, inhibiting PI3K using LY294002 could not absolutely abrogate the protective effects of geraniin, thus suggesting that other pathways may be involved in the actions of geraniin. Numerous studies have indicated that geraniin activates the PI3K/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways (25,38). Whether MAPK or other pathways also contribute to the beneficial effects of geraniin requires further study. Furthermore, the stromal cell-derived factor 1/C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) axis serves a vital role in mobilization and recruitment of MSCs to the infarcted area (39). PI3K/Akt activation has also been demonstrated to induce an increase in CXCR4 expression in MSCs (40). Whether geraniin may promote CXCR4 expression via the PI3K/Akt pathway remains unknown and requires further research.

In conclusion, the present study provided preliminary evidence to suggest that geraniin exerts prosurvival effects on MSCs against H2O2-induced cellular oxidative stress, predominantly by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. These findings indicated that geraniin may be considered a potential drug to enhance MSC-based therapeutic efficacy for the future treatment of MI.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 30800233 to Y.Z.; grant no. 81330033 to B.Y.).

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ripa RS, Haack-Sørensen M, Wang Y, Jørgensen E, Mortensen S, Bindslev L, Friis T, Kastrup J. Bone marrow derived mesenchymal cell mobilization by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor after acute myocardial infarction: Results from the Stem Cells in Myocardial Infarction (STEMMI) trial. Circulatio. 2007;116(Suppl 11):I24–I30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z, Liang D, Gao X, Zhao C, Qin X, Xu Y, Su T, Sun D, Li W, Wang H, et al. Selective inhibition of inositol hexakisphosphate kinases (IP6Ks) enhances mesenchymal stem cell engraftment and improves therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2014;109:417. doi: 10.1007/s00395-014-0417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karantalis V, Hare JM. Use of mesenchymal stem cells for therapy of cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:1413–1430. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher SA, Zhang H, Doree C, Mathur A, Martin-Rendon E. Stem cell treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD006536. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006536.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geng YJ. Molecular mechanisms for cardiovascular stem cell apoptosis and growth in the hearts with atherosclerotic coronary disease and ischemic heart failure. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;1010:687–697. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:31–47. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logue SE, Gustafsson AB, Samali A, Gottlieb RA. Ischemia/ reperfusion injury at the intersection with cell death. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quideau S, Deffieux D, Douat-Casassus C, Pouységu L. Plant polyphenols: Chemical properties, biological activities, and synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:586–621. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang NJ, Shin SH, Lee HJ, Lee KW. Polyphenols as small molecular inhibitors of signaling cascades in carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:310–324. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marín L, Miguélez EM, Villar CJ, Lombó F. Bioavailability of dietary polyphenols and gut microbiota metabolism: Antimicrobial properties. BioMed Res Int. 2015;905215 doi: 10.1155/2015/905215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habtemariam S, Varghese GK. The antidiabetic therapeutic potential of dietary polyphenols. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2014;15:391–400. doi: 10.2174/1389201015666140617104643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins AR. Assays for oxidative stress and antioxidant status: Applications to research into the biological effectiveness of polyphenols. Am J Clin Nut. 2005;81(Suppl 1):261S–267S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.261S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu N, Zu Y, Fu Y, Kong Y, Zhao J, Li X, Li J, Wink M, Efferth T. Antioxidant activities and xanthine oxidase inhibitory effects of extracts and main polyphenolic compounds obtained from Geranium sibiricum L. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:4737–4743. doi: 10.1021/jf904593n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Londhe JS, Devasagayam TP, Foo LY, Shastry P, Ghaskadbi SS. Geraniin and amariin, ellagitannins from Phyllanthus amarus, protect liver cells against ethanol induced cytotoxicity. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:1562–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang KA, Lee IK, Zhang R, Piao MJ, Kim KC, Kim SY, Shin T, Kim BJ, Lee NH, Hyun JW. Radioprotective effect of geraniin via the inhibition of apoptosis triggered by γ-radiation-induced oxidative stress. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2011;27:83–94. doi: 10.1007/s10565-010-9172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Li J, Peng X, Lv B, Wang P, Zhao X, Yu B. Geraniin inhibits LPS-induced THP-1 macrophages switching to M1 phenotype via SOCS1/NF-κB pathway. Inflammation. 2016;39:1421–1433. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang F, Cui J, Lv B, Yu B. Nicorandil protects mesenchymal stem cells against hypoxia and serum deprivation-induced apoptosis. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36:415–423. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang LL, Liu JJ, Liu F, Liu WH, Wang YS, Zhu B, Yu B. MiR-499 induces cardiac differentiation of rat mesenchymal stem cells through wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;420:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang XY, Fan XS, Cai L, Liu S, Cong XF, Chen X. Lysophosphatidic acid rescues bone mesenchymal stem cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2015;20:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou H, Li D, Shi C, Xin T, Yang J, Zhou Y, Hu S, Tian F, Wang J, Chen Y. Effects of exendin-4 on bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis in vitro. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12898. doi: 10.1038/srep12898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maryanovich M, Gross A. A ROS rheostat for cell fate regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson DT, Harris RA, Blair PV, Balaban RS. Functional consequences of mitochondrial proteome heterogeneity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C698–C707. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00109.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brand MD, Buckingham JA, Esteves TC, Green K, Lambert AJ, Miwa S, Murphy MP, Pakay JL, Talbot DA, Echtay KS. Mitochondrial superoxide and aging: Uncoupling-protein activity and superoxide production. Biochem Soc Symp. 2004;71:203–213. doi: 10.1042/bss0710203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang P, Peng X, Wei ZF, Wei FY, Wang W, Ma WD, Yao LP, Fu YJ, Zu YG. Geraniin exerts cytoprotective effect against cellular oxidative stress by upregulation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzyme expression via I3K/AKT and ERK1/2 pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850:1751–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, Melo LG, Morello F, Mu H, Noiseux N, Zhang L, Pratt RE, Ingwall JS, et al. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nm0405-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hare JM, Fishman JE, Gerstenblith G, DiFede Velazquez DL, Zambrano JP, Suncion VY, Tracy M, Ghersin E, Johnston PV, Brinker JA, et al. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: The POSEIDON randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:2369–2379. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amado LC, Schuleri KH, Saliaris AP, Boyle AJ, Helm R, Oskouei B, Centola M, Eneboe V, Young R, Lima JA, et al. Multimodality noninvasive imaging demonstrates in vivo cardiac regeneration after mesenchymal stem cell therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2116–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toma C, Pittenger MF, Cahill KS, Byrne BJ, Kessler PD. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation. 2002;105:93–98. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urao N, Ushio-Fukai M. Redox regulation of stem/progenitor cells and bone marrow niche. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;54:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gechev TS, Hille J. Hydrogen peroxide as a signal controlling plant programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:17–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitzpatrick DF, Hirschfield SL, Coffey RG. Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxing activity of wine and other grape products. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H774–H778. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.2.H774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheng R, Gu ZL, Xie ML, Zhou WX, Guo CY. EGCG inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and protects cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:191–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sangeetha P, Das UN, Koratkar R, Suryaprabha P. Increase in free radical generation and lipid peroxidation following chemotherapy in patients with cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90139-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andón FT, Fadeel B. Programmed cell death: Molecular mechanisms and implications for safety assessment of nanomaterials. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:733–742. doi: 10.1021/ar300020b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garrido C, Galluzzi L, Brunet M, Puig PE, Didelot C, Kroemer G. Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1423–1433. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gnecchi M, He H, Melo LG, Noiseaux N, Morello F, de Boer RA, Zhang L, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ, Ingwall JS. Early beneficial effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing Akt on cardiac metabolism after myocardial infarction. Stem Cells. 2009;27:971–979. doi: 10.1002/stem.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhai JW, Gao C, Ma WD, Wang W, Yao LP, Xia XX, Luo M, Zu YG, Fu YJ. Geraniin induces apoptosis of human breast cancer cells MCF-7 via ROS-mediated stimulation of 38 MAPK. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2016;26:311–318. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2016.1139025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaruba MM, Theiss HD, Vallaster M, Mehl U, Brunner S, David R, Fischer R, Krieg L, Hirsch E, Huber B, et al. Synergy between CD26/DPP-IV inhibition and G-CSF improves cardiac function after acute myocardial infarction. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ping YF, Yao XH, Jiang JY, Zhao LT, Yu SC, Jiang T, Lin MC, Chen JH, Wang B, Zhang R, et al. The chemokine CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 promote glioma stem cell-mediated VEGF production and tumour angiogenesis via I3K/AKT signalling. J Pathol. 2011;224:344–354. doi: 10.1002/path.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]