Highlights

-

•

Spontaneous splenic rupture should be considered in patients presenting with peritonism without preceding trauma.

-

•

Haematological and infectious causes, including Varicella Zoster, should be sought when investigating spontaneous splenic rupture.

-

•

There is limited published guidance regarding the surgical options when faced with spontaneous splenic rupture.

Keywords: General surgery, Infectious disease, Varicella zoster, Splenectomy

Abstract

Introduction

Here we present a case of atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to varicella infection requiring emergency splenectomy. The presentation was as would be expected for epstein barr virus (EBV) related splenic injury, which is well documented in the literature. Dermatological findings however suggested varicella zoster, and viral serology subsequently confirmed the diagnosis.

Presentation of case

A young Romanian male presented to the emergency department with peritonism without preceding trauma. Free fluid on USS was aspirated as frank blood and cross-sectional imaging demonstrated a ruptured spleen. He underwent emergency splenectomy and recovered well. During his presentation he was noted to have an erythematous rash with different rates of evolution raising the suspicion for Varicella Zoster. This was subsequently confirmed on viral serology.

Discussion

A number of precedents have been identified for spontaneous splenic rupture, however Varicella Zoster has only been reported a handful of times. A number of surgical options are available for splenic rupture, and guidelines exist for traumatic splenic injury. There is limited guidance on the most effective surgical management for spontaneous splenic ruptures with haemodyamic compromise.

Conclusion

Atraumatic splenic rupture should be considered as an important differential in those presenting with abdominal pain and peritonism without a history of preceding trauma. Haematological and infectious diagnoses should be sought to identify causation for the splenic rupture.

1. Introduction

Splenic rupture typically presents as left upper quadrant pain, peritonism, and haemodynamic compromise. The diagnosis is made with clinical suspicion being confirmed on ultrasound and/or computed tomography (CT). Reflecting the aetiology of the injury, splenic ruptures are considered either traumatic or atraumatic. Abdominal injury leading to immediate and delayed traumatic splenic rupture is a well recognised event [1]. Whilst less common [2], atraumatic rupture of the spleen is also widely documented in the literature and is associated with a pathological precedent in 93% of cases [3]. Infection precedes 27.3% of atraumatic splenic ruptures and is commonly related to Epstein-Barr virus and malaria [[3], [4], [5]].

Varicella zoster (VZV) is a highly infectious member of the human herpes viruses, often presenting as chickenpox in childhood leading to approximately 90% immunity amongst adults [6]. Following primary infection VZV remains dormant in dorsal root ganglia where it can reactivate in adulthood as herpes zoster. Systemic complications of VZV such as pneumonitis and encephalitis are rare and largely associated with the immunosuppressed population [7]. Here we present a rare case of atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to VZV presenting to a large district general hospital with emergency surgery capabilities.

Note this case report has been constructed in accordance with the SCARE guidelines [17].

2. Presentation of case

A 32 year old male presented to the accident and emergency department complaining of a 2 day history of worsening abdominal pain and chest pain. There were no other associated symptoms; notably his bowels had opened normally, he had no urinary symptoms, and there was no stigmata of systemic viral disease such as a sore throat nor rash. He could not recall any recent traumatic injury. There was no past medical/surgical history and he had no known unwell personal contacts.

His observations at presentation were a temperature of 36.8 ° centigrade, oxygen saturations 100% in room air, respiratory rate 16, blood pressure 164/99, and heart rate 108, giving him a national early warning score of [8].

Physical examination demonstrated an alert, acutely unwell adult male. He had a distended abdomen with generalised tenderness, involuntary guarding throughout and evidence of peritonism. There was no palpable organomegaly at time of examination. He had no palpable lymphadenopathy or evidence of enlarged or exudative tonsils. Cardiorespiratory examination was normal.

Laboratory investigations revealed: Hb 120 g/L, WCC 5.5 × 10*9, platelet count 109 × 10*9, CRP 59.2, Creatinine 116, Urea 10.1, Amylase 37, lactate 0.8. A repeated haemoglobin test demonstrated a fall in levels to 104 g/L on full blood count.

The patient subsequently underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen and pelvis with contrast (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). This demonstrated an enlarged spleen with a contained collection lateral to the spleen, consistent with a substantial sub-capsular haematoma. Free-intra abdominal fluid was also demonstrated which was subsequently aspirated under USS guidance and confirmed as blood. A CT mesenteric angiogram (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) was performed which demonstrating irregularity in the superior anterolateral corner of the spleen, confirming splenic rupture. No arterial aneurysm were identified including those of the splenic artery.

Fig. 1.

CT abdomen (axial) demonstrating sub-capsular splenic haematoma.

Fig. 2.

CT abdomen (coronal) demonstrating sub-capsular splenic haematoma.

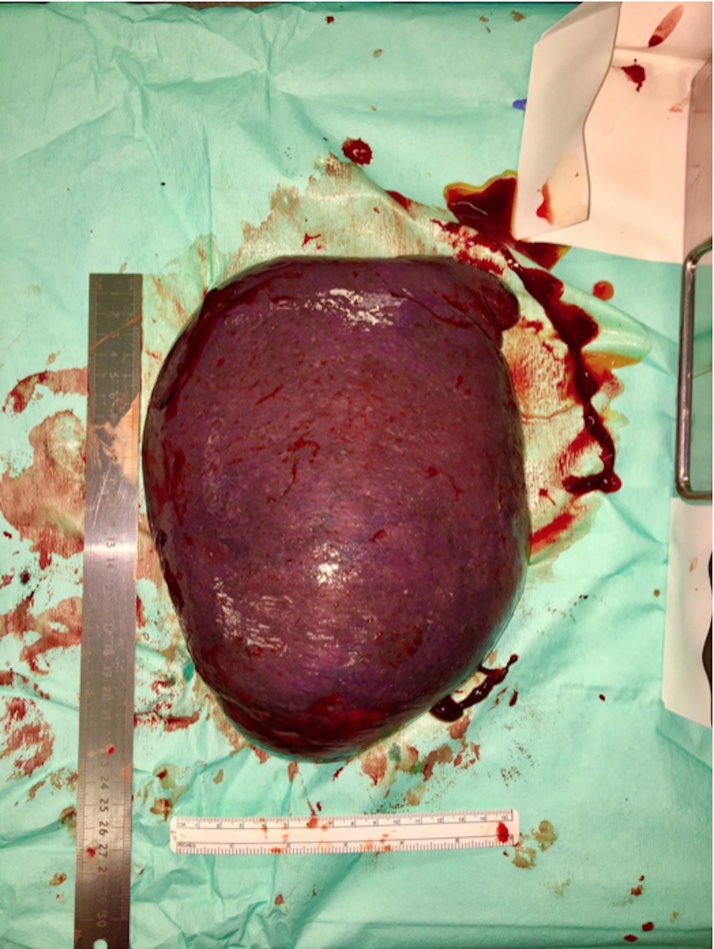

The patient was initially resuscitated and an emergency open splenectomy was performed. A ruptured splenic capsule with a large adherent haematoma was identified at laparotomy (Fig. 3). The spleen was medialised and the splenic vessels controlled and ligated at the hilum, allowing safe excision of the spleen

Fig. 3.

Enlarged spleen retrieved at laparotomy.

In light of the atraumatic splenic rupture in the presence of splenomegaly a viral screen was performed. The initial screen did not include varicella. Immunoglobulin quantification and autoantibody testing including a direct antiglobulin test were also performed:

CMV IgG positive (evidence of previous infection)

CMV IgM negative

EBV VCA IgG/IgM negative

EBV EBNA IgG positive (evidence of EBV infection over 8 weeks ago)

Heb B SAg non reactive

Hep C abs non reactive

HIV-1/-2 abs non reactive

The patient was reviewed by infectious diseases team who commented on a new rash with erythematous clusters with different rates of evolution. They also reported a palpable spleen. Based on this finding the impression was a varicella induced systemic illness, with subsequent spontaneous splenic rupture. He was commenced on acyclovir, and varicella and herpes simplex serology was sent which confirmed this suspicion:

Varicella Zoster DNA detected

Herpes simplex type 1 not detected

Herpes simplex type 2 not detected

The patient was commenced on long term phenoxymethylpenicillin and given appropriate post-splenectomy vaccinations. The patient was followed up by both the surgical and infectious diseases team.

As a non-English speaking patient communication was complex from the beginning of this case. He was able to express his concern and lack of understanding of why this has happened, particularly without any trauma. With translators assisting we were able to explain his diagnosis which alleviated some of his concerns and he was able to inform his family of the VZV diagnosis. He recovered well, was very pleased with his post operative course, and understands the importance of regular antibiotics.

3. Discussion

This case has demonstrated a rare occurrence of atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to VZV. In 2012 a systematic review of 613 cases of splenic rupture from 1950 to 2011 identified 143 infection associated ruptures [9], only one of these was varicella related [10]. The most common infections presented by this review were malaria (65 reports) and EBV (42 reports). An extended literature search identified only 3 other cases of varicella induced spontaneous splenic rupture [[11], [12], [13]] making this the 5th reported case in the literature. All reported cases have shared features in the patient demographics of a young male and expected dermatological findings for VZV preceding the onset of abdominal pain.

The case illustrates effective use of the hospital multi-disciplinary team to accurately diagnose and promptly manage what was an acutely life threatening event. The patient was quickly referred to the general surgeons in the emergency department who then involved the infectious disease and haematology physicians in the pre-operative diagnostic work up. Without a clear precedent of trauma, atypical causes of splenic rupture should be considered. These include neoplasm, haematological disease, and infection as with the case presented here. When faced with splenic injury the Orloff Peskin criteria can be referred to which state that atraumatic rupture is likely if the following 4 criterion are met: 1) a history of no recent trauma; 2) no evidence of systemic disease is other organs that may precipitate rupture; 3) no peri-splenic adhesions/scarring suggestive of previous injury; 4) macroscopically and histologically normal spleen [14].

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) have published guidance on the management of traumatic splenic rupture [15]. Depending on the extent of injury and involvement of the hilum, intervention may involve total splenectomy, splenic conservation surgery, selective splenic arterial embolization, or observation and conservative care [16]. The guidance for atraumatic rupture however is limited. It is likely that embolization of the splenic artery and splenic conservation surgery have a minimal role to play in the context of a pathological spleen and thus the mainstay of management for atraumatic rupture is total splenectomy or conservative care. Of the varicella induced splenic ruptures in the literature, 3 were managed with splenectomy and one conservatively. In the case presented here, a substantial sub-capsular haematoma was suggestive of a significant splenic rupture (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). This was confirmed on CT mesenteric angiography, prompting total open splenectomy.

The standard of care in asplenic patients is widely accepted as vaccination against haemophilus influenzae, meningococci, pneumococci, and influenza virus, and antibiotic prophylaxis [16]. This was adhered to with the case presented who is continuing to receive phenoxymethylpenicillin. Lifelong prophylaxis is recommended in those who have suffered a bout of post splenectomy sepsis and initial prophylaxis is mandatory in asplenic children under 5 years old. Otherwise the decision for antimicrobial prophylaxis should be made on an individual basis considering factors such as age at time of surgery, reason for rupture, and presence of existing haemoglobinopathy [16].

4. Conclusion

Atraumatic splenic rupture should be considered as an important differential in those presenting with abdominal pain and peritonism without a history of preceding trauma. The cause of splenic rupture in these cases can cause diagnostic uncertainty and should be managed under joint care with general surgeons and physicians. VZV is a rare cause of atraumatic splenic rupture but should be considered alongside other more common infectious precedents, neoplasm, and haematological disease.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This is a single case review and will not require ethics approval from the Research Ethics Committee and does not need to go through the HRA assessment process.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request

Author contribution

MS - manuscript writing and review

BA - manuscript writing and review

LJ - manuscript review

SB - manuscript review

Guarantor

Mark Sykes

References

- 1.Olsen W.R., Polley T.Z. A second look at delayed splenic rupture. Arch. Surg. 1977;112(April (4)):422–425. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1977.01370040074012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leijnen D., Steur W., Brekelmans W. Non-traumatic rupture of the spleen: an atypical presentation of the acute abdomen. Abdominal Surg. 2011;28 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renzulli P., Hostettler A., Schoepfer A.M. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br. J. Surg. 2009;96(October (10)):1114–1121. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halkic N., Vuilleumier H., Qanadli S.D. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis treated by embolization of the splenic artery. Can. J. Surg. 2004;47(June (3)):221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Won A.C., Ethell A. Spontaneous splenic rupture resulted from infectious mononucleosis. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2012;3(December (3)):97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health England. (2015). The Green Book. Chapter 34. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/456562/Green_Book_Chapter_34_v3_0.pd. (Accessed 8 May 2017).

- 7.Tunbridge A.J., Breuer J., Jeffery K.J. Chickenpox in adults-Clinical management. J. Infect. 2008;57(August (2)):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Early Warning Score. National Clinical Guideline No.1. http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/NEWSFull-ReportAugust2014.pdf. (Accessed 7 June 2017).

- 9.Aubrey-Bassler F.K., Sowers N. 613 cases of splenic rupture without risk factors or previously diagnosed disease: a systematic review. BMC Emerg. Med. 2012;12(August (1)):11. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vial I., Hamidou M., Coste-Burel M. Abdominal pain in varicella: an unusual cause of spontaneous splenic rupture. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2004;11(June (3)):176–177. doi: 10.1097/01.mej.0000104026.33339.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifton L.J., Dhaliwal K.S., Saif D. Varicella zoster virus infection is an unusual cause of splenic rupture. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015(August) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210909. bcr2015210909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapp E. Ruptured spleen associated with chicken-pox. Br. Med. J. 1969;1(March (5644)):617. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5644.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris R.A., Boland S.L. Varicella zoster associated with spontaneous splenic rupture. ANZ J. Surg. 1998;68(February (2)):162–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orloff M. Spontaneous rupture of the normal spleen, a surgical enigma. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1958;106:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Injury Scoring Scales. http://www.aast.org/Library/TraumaTools/InjuryScoringScales.aspx. (Accessed 7 June 2017).

- 16.Rubin L.G., Schaffner W. Care of the asplenic patient. New Engl. J. Med. 2014;371(July (4)):349–356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1314291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]