Abstract

Background

Marijuana is a widely used recreational substance. Few cases have been reported of acute myocardial infarction following marijuana use. To our knowledge, this is the first ever study analyzing the lifetime odds of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) with marijuana use and the outcomes in AMI patients with versus without marijuana use.

Methods

We queried the 2010-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database for 11-70-year-old AMI patients. Pearson Chi-square test for categorical variables and Student T-test for continuous variables were used to compare the baseline demographic and hospital characteristics between two groups (without vs. with marijuana) of AMI patients. The univariate and multivariate analyses were used to assess and compare the clinical outcomes between two groups. We used Cochran–Armitage test to measure the trends. All statistical analyses were executed by IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). We used weighted data to produce national estimates in our study.

Results

Out of 2,451,933 weighted hospitalized AMI patients, 35,771 patients with a history of marijuana and 2,416,162 patients without a history of marijuana use were identified. The AMI-marijuana group consisted more of younger, male, African American patients. The length of stay and mortality rate were lower in the AMI-marijuana group with more patients being discharged against medical advice. Multivariable analysis showed that marijuana use was a significant risk factor for AMI development when adjusted for age, sex, race (adjusted OR 1.079, 95% CI 1.065-1.093, p<0.001); adjusted for age, female, race, smoking, cocaine abuse (adjusted OR 1.041, 95% CI 1.027-1.054, p<0.001); and also when adjusted for age, female, race, payer status, smoking, cocaine abuse, amphetamine abuse and alcohol abuse (adjusted OR: 1.031, 95% CI: 1.018-1.045, p<0.001). Complications such as respiratory failure (OR 18.9, CI 15.6-23.0, p<0.001), cerebrovascular disease (OR 9.0, CI 7.0-11.7, p<0.001), cardiogenic shock (OR 6.0, CI 4.9-7.4, p<0.001), septicemia (OR 1.8, CI 1.5–2.2, p<0.001), and dysrhythmia (OR 1.8, CI 1.5-2.1, p<0.001) were independent predictors of mortality in AMI-marijuana group.

Conclusion

The lifetime AMI odds were increased in recreational marijuana users. Overall odds of mortality were not increased significantly in AMI-marijuana group. However, marijuana users showed higher trends of AMI prevalence and related mortality from 2010-2014. It is crucial to assess cardiovascular effects related to marijuana overuse and educate patients for the same.

Keywords: marijuana, cannabis, acute myocardial infarction, substance abuse, mortality, trend, myocardial infarction, nationwide, cardiovascular, recreational

Introduction

In addition to alcohol and tobacco, cannabis is one of the most abused substances globally [1]. It is an extensively used recreational substance [2]. Few states in the United States of America (USA) currently have laws broadly legalizing marijuana in some form. With the rise in cannabis legalization across the USA, the prevalence of marijuana use is expected to grow. Some studies reported that marijuana use affects the cardiovascular system, posing a risk in older people with coronary heart disease and with tachycardia at rest [3]. In other study and few case reports, the risk of myocardial infarction increased nearly five times after 1-hour post marijuana smoking when compared to marijuana non-smoking period [4, 5]. The results of long-term use of marijuana have been reported in very few studies, with no increased risk of mortality in the age group of younger than 50 years [6]. However, the literature remains contentious with regard to this issue and additional studies are required to elucidate the potential relationship between marijuana use and cardiovascular events. The current study was designed to analyze the acute myocardial infarction (AMI) prevalence with marijuana use, the odds of AMI incidence with marijuana use, and the predictors of inpatient mortality in AMI with marijuana use.

Materials and methods

We analyzed a population-based sample of AMI patients from the 2010 to 2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) Database of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) sponsored by Healthcare Research and Quality Agency (AHRQ). NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient healthcare database which is publicly accessible in the United States. NIS database comprises a 20% sample inpatient from 1000 hospitals of more than 40 states which contain an average of seven million unweighted discharges per year. This data estimate results for more than 35 million weighted hospitalizations of the US population [7].

In our study, the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) diagnosis code 100 was used to recognize the AMI patients aged 11 to 70 years. Of these, histories of marijuana dependence and non-dependent marijuana use were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 304.30, 304.31, 304.32, 305.20, 305.21, and 305.22. The approach has already been used before to precisely distinguish patients with a history of recreational use of marijuana [8]. Moreover, we examined patients’ baseline demographic and hospital details between two groups AMI-marijuana vs. AMI-non marijuana as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Hospitalized Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients with known Marijuana Use.

SNF: skilled nursing facility, ICF: intermediate care facility

| Variables | AMI without Marijuana | AMI with Marijuana | P-value* |

| Unweighted Index admissions | 487,317 | 7,202 | |

| Weighted Index admissions | 2,416,162 | 35,771 | |

| Age in years at admission | <0.001 | ||

| Mean age ± SD | 57.79 ± 8.98 | 49.34 ± 10.80 | |

| 11-25 | 0.3% | 2.5% | |

| 26-40 | 4.2% | 18.0% | |

| 41-55 | 31.0% | 50.1% | |

| 56-70 | 64.5% | 29.4% | |

| Weekend Admissions | <0.001 | ||

| Monday-Friday | 74.2% | 71.6% | |

| Saturday-Sunday | 25.8% | 28.4% | |

| Died during hospitalization | <0.001 | ||

| Did not die | 94.2% | 96.6% | |

| Died | 5.8% | 3.4% | |

| Disposition of Patient | <0.001 | ||

| Routine | 66.0% | 74.0% | |

| Transfer to short-term hospital | 8.6% | 6.9% | |

| Other Transfers (SNF, ICF, another facility) | 9.1% | 4.9% | |

| Home Health Care | 9.3% | 6.8% | |

| Against Medical Advice (AMA) | 1.2% | 4.0% | |

| Died | 5.8% | 3.4% | |

| Elective vs. Non-elective Admissions | <0.001 | ||

| Non-elective | 91.7% | 94.8% | |

| Elective | 8.3% | 5.2% | |

| Indicator of Sex | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 66.0% | 76.9% | |

| Female | 34.0% | 23.1% | |

| Length of stay (cleaned) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean length of stay (days) ±SD | 5.65 ± 8.01 | 4.74 ± 5.94 | |

| ≤3 days | 54.4% | 58.7% | |

| 4 to 6 days | 20.3% | 21.8% | |

| 7 to 9 days | 10.1% | 8.8% | |

| 10 to 12 days | 5.5% | 4.5% | |

| ≥13 days | 9.7% | 6.2% | |

| Primary Expected Payer | <0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 36.6% | 20.6% | |

| Medicaid | 11.9% | 26.9% | |

| Private including HMO | 37.4% | 22.5% | |

| Self - Pay | 9.3% | 22.9% | |

| No charge | 0.9% | 2.2% | |

| Other | 3.9% | 4.9% | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 71.4% | 55.4% | |

| Black | 13.8% | 33.0% | |

| Hispanic | 8.4% | 6.8% | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2.4% | 0.7% | |

| Native American | 0.7% | 0.9% | |

| Other | 3.4% | 3.3% | |

| Median Household Income Quartile on Patient’s ZIP | <0.001 | ||

| $1 - $39, 999 | 32.2% | 44.0% | |

| $40, 000 - $50,999 | 27.0% | 26.4% | |

| $51, 000 - $65, 999 | 23.2% | 18.9% | |

| $66, 000 + | 17.7% | 10.6% | |

| Total charges (Mean) | $85,702.22 | $76,272.23 | <0.001 |

| Bed Size of Hospital¥ | 0.001 | ||

| Small | 10.6% | 10.0% | |

| Medium | 24.5% | 24.4% | |

| Large | 64.9% | 65.6% | |

| Location/Teaching Status of Hospital | <0.001 | ||

| Rural | 8.9% | 6.3% | |

| Urban - non teaching | 36.7% | 32.1% | |

| Urban - teaching | 54.4% | 61.7% | |

| *Significant P-values ≤ 0.05 at 95% confidence Interval, ¥ The bed size cutoff points divided into small, medium, and large have been done so that approximately one-third of the hospitals in a given region, location, and teaching status combination would fall within each bed size category. Derived from https://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/db/vars/hosp_bedsize/nisnote.jsp | |||

AHRQ co-morbidities and other related co-morbidities were also scrutinized as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Comorbidities in Hospitalized Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients with known Marijuana Use.

| Variables | AMI without Marijuana | AMI with Marijuana | P-value* |

| Comorbidities# | |||

| AIDS | 0.3% | 1.0% | <0.001 |

| Motor Vehicle Accident | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.218 |

| Septicemia | 8.2% | 5.0% | <0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal | |||

| RA/CVD | 2.3% | 1.5% | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular | |||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 7.6% | 5.8% | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 58.9% | 50.6% | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerosis | 8.7% | 6.6% | <0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 8.4% | 12.1% | <0.001 |

| Thromboembolism | 4.3% | 3.5% | <0.001 |

| Previous MI | 10.7% | 12.9% | <0.001 |

| Family History of CAD | 10.7% | 13.7% | <0001 |

| Previous PCI | 15.6% | 14.5% | <0.001 |

| Previous CABG | 6.7% | 3.8% | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 5.4% | 3.5% | <0.001 |

| History of SCA | 0.6% | 0.7% | <0.001 |

| Valvular Disease | 1.9% | 1.6% | <0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 10.6% | 7.9% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 67.6% | 62.8% | <0.001 |

| Dysrhythmia | 25.6% | 23.0% | <0.001 |

| Vasopressor Infusion | 1.4% | 1.1% | <0.001 |

| Post-MI Dressler’s Syndrome | 0.3% | 0.4% | <0.001 |

| Left Ventricular Failure | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.628 |

| Respiratory | |||

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 21.5% | 22.4% | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorders | 1.7% | 1.0% | <0.001 |

| Respiratory Failure | 18.7% | 15.8% | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 9.3% | 7.0% | <0.001 |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 8.1% | 5.2% | <0.001 |

| Neurological | |||

| Paralysis | 2.3% | 1.6% | <0.001 |

| Other Neurological Disorders | 5.4% | 6.5% | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 2.8% | 2.7% | 0.133 |

| Transient Ischemic Attacks | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.057 |

| Psychiatry | |||

| Depression | 8.6% | 10.9% | <0.001 |

| Psychoses | 3.5% | 8.4% | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 5.1% | 22.6% | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 46.3% | 75.9% | <0.001 |

| Cocaine Abuse | 1.2% | 18.9% | <0.001 |

| Amphetamine Abuse | 0.3% | 5.6% | <0.001 |

| Drug Abuse | 3.3% | 99.5% | <0.001 |

| Hemato-oncological | |||

| Deficiency Anemia | 15.7% | 12.1% | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 6.6% | 6.1% | <0.001 |

| Weight Loss | 4.2% | 3.6% | <0.001 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 1.2% | 0.4% | <0.001 |

| Solid Tumor without Metastasis | 1.3% | 0.7% | <0.001 |

| Endocrinological | |||

| Diabetes, Uncomplicated | 30.0% | 18.3% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes with Chronic Complications | 8.4% | 4.7% | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 7.8% | 3.7% | <0.001 |

| Renal | |||

| Renal Failure | 16.5% | 10.3% | <0.001 |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | 25.4% | 27.3% | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 5.4% | 2.7% | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||

| Liver Disease | 2.7% | 4.5% | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 19.2% | 15.3% | <0.001 |

| *Significant P-values ≤ 0.05 at 95% confidence Interval, #Variables are AHRQ Co-morbidity measures | |||

| Abbreviations: AIDS – Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, RA/CVD – Rheumatoid Arthritis/ Collagen Vascular Disease, MI – Myocardial Infarction, CAD – Coronary Artery Disease, PCI – Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, CABG – Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting, SCA – Sudden Cardiac Arrest | |||

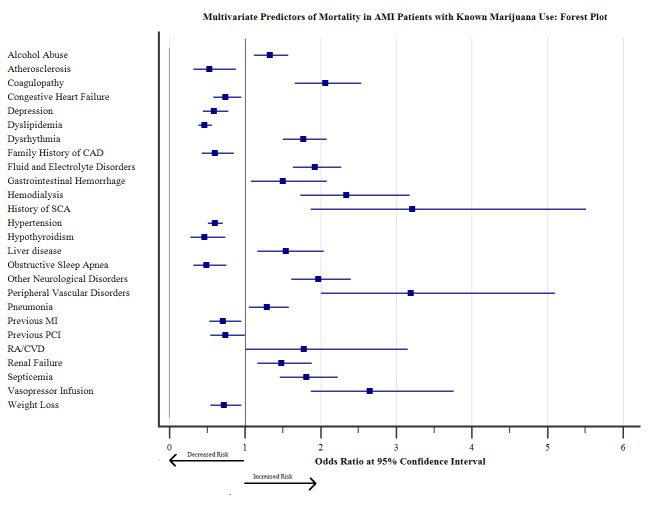

We also assessed the trends of AMI prevalence and AMI-related mortality in 11-70 years old marijuana users as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Trends of AMI Prevalence and Mortality per 100,000 Marijuana Users in the United States .

The primary outcome in our study was the prevalence of AMI, predictors of AMI incidence and inpatient mortality and secondary outcomes included the length of stay (LOS), total hospital charges, and complications. We used ICD-9 CM codes and Clinical Classification Software codes to identify the comorbidities which were not classified in NIS database shown in the appendix.

Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables and Student t-test for continuous variables were used to compare the baseline demographic and hospital characteristics between two groups (without vs. with marijuana) of AMI patients. A two side tailed p-value <0.05 was considered to determine the statistical significance. The categorical variables were measured in percentages, and continuous variables were expressed in mean±SD. We evaluated odds of AMI incidence and in-hospital mortality in AMI with marijuana use by univariate analysis and then clinically significant relevant patients’ variables were incorporated in multivariate logistic regression after adjusting for potential confounders including demographic and hospital criteria, history of substance abuse, and other relevant comorbidities. Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval, and p-value were used to report logistic regression results. The multivariate regression model was adjusted for potential confounders such as age, race, sex, median household income, smoking, and cocaine abuse to assess the odds of AMI incidence in marijuana users (Table 3). The multivariate regression models for inpatient mortality was adjusted for confounding factors such as age, race, the length of stay, the median house of income in the zip code, an indicator of sex, hospital bed size, smoking and cocaine abuse. The trends of baseline demographics, AMI prevalence and complications from 2010-2014 were measured by Cochran–Armitage test. All statistical analyses were executed by IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). We used weighted data to produce national estimates in our study. Institutional Review Board authorization was not needed in this study because NIS database does not contain patients’ identification details.

Table 3. Multivariate Predictors of Acute Myocardial Infarction with known Marijuana Use.

MI: myocardial infarction, CAD: coronary artery disease, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting.

| Variables | Adjusted Odds Ratio$ | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value* | |

| Age in years at admission | ||||

| 11-25 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 26-40 | 4.141 | 3.848 | 4.457 | <0.001 |

| 41-55 | 9.099 | 8.463 | 9.782 | <0.001 |

| 56-70 | 11.510 | 10.678 | 12.406 | <0.001 |

| Indicator of Sex | ||||

| Male vs. Female | 1.507 | 1.465 | 1.549 | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 0.802 | 0.750 | 0.857 | <0.001 |

| Black | 0.697 | 0.651 | 0.747 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.702 | 0.649 | 0.760 | <0.001 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.766 | 0.659 | 0.889 | <0.001 |

| Native American | 0.693 | 0.600 | 0.802 | <0.001 |

| Other | Referent | Referent | ||

| Comorbidities# | ||||

| Smoking | 1.695 | 1.650 | 1.742 | <0.001 |

| Cocaine | 1.106 | 1.073 | 1.140 | <0.001 |

| AIDS | 1.221 | 1.083 | 1.377 | 0.001 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0.789 | 0.748 | 0.831 | <0.001 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 0.838 | 0.814 | 0.862 | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.663 | 1.582 | 1.749 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, Uncomplicated | 0.941 | 0.911 | 0.971 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes with Complications | 0.797 | 0.753 | 0.844 | <0.001 |

| Drug Abuse | 16.182 | 13.824 | 18.942 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.536 | 1.495 | 1.579 | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.708 | 0.666 | 0.753 | <0.001 |

| Liver Disease | 0.702 | 0.664 | 0.742 | <0.001 |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | 1.278 | 1.245 | 1.313 | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 1.264 | 1.222 | 1.307 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorder | 1.676 | 1.538 | 1.827 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorder | 0.734 | 0.652 | 0.827 | <0.001 |

| Renal Failure | 1.057 | 1.014 | 1.103 | 0.010 |

| Valvular Diseases | 0.692 | 0.629 | 0.761 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3.275 | 3.188 | 3.363 | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerosis | 0.849 | 0.773 | 0.931 | 0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 2.715 | 2.612 | 2.823 | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 0.668 | 0.621 | 0.718 | <0.001 |

| Oral Contraceptive Pills | 0.726 | 0.583 | 0.905 | 0.004 |

| Thromboembolism | 0.775 | 0.728 | 0.824 | <0.001 |

| Previous MI | 1.101 | 1.056 | 1.148 | <0.001 |

| Family History of CAD | 4.481 | 4.315 | 4.652 | <0.001 |

| Previous PCI | 2.443 | 2.344 | 2.546 | <0.001 |

| Previous CABG | 0.896 | 0.839 | 0.957 | 0.001 |

| History of Sudden Cardiac Arrest | 3.899 | 3.313 | 4.589 | <0.001 |

| *Significant P-value ≤ 0.05 at 95% Confidence Interval, #Variables are AHRQ Co-morbidity measures. $Regression model adjusted for age, race, sex, drug abuse, cocaine abuse, other relevant comorbidities and hospital characteristics | ||||

Results

Study population

We identified 2,451,933 weighted hospitalized AMI patients from the 2010 –2014 NIS database. Of these, there were 35,771 patients with a history of marijuana and 2,416,162 patients without a history of marijuana use. The mean age (years) was 49.3 ± 10.7 in the AMI-marijuana group as compared to 57.7 ± 8.9 in AMI non-marijuana group. AMI-marijuana group consisted more of younger, male (76.9% vs. 66.0%), black (33.0% vs. 13.8%) patients with more Medicaid enrollees (26.9% vs. 11.9%) compared to the non-marijuana group. In White, Hispanic and Asian ethnicities, males had a higher prevalence of AMI with marijuana use while in the Black race, females had a higher prevalence of AMI in marijuana users. The age group 41-55 years had the highest prevalence (50.1%) of AMI with marijuana use.

The disposition by 'against medical advice' was higher in AMI with marijuana patients (4.0% vs.1.2%). Urban – teaching hospital documented more of AMI patients with marijuana use (61.7% vs. 54.4%). The low-income group ($1 - $39,999) had a higher number of AMI-marijuana group patients as compared to AMI-non marijuana group (44.0% vs. 32.2%). Weekend hospital admissions were increased in AMI with marijuana patients (28.4% vs. 25.8%) as compared to AMI without marijuana patients. Inpatient mortality rate was found lower in AMI with marijuana group (3.4% vs. 5.8%) (Table 1).

Co-morbidities such as cardiomyopathy, previous myocardial infarction (MI), family history of coronary artery disease, chronic pulmonary disease, other neurological disorders, depression, psychosis, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, smoking, cocaine abuse, amphetamine abuse, fluid and electrolytes disorders, and liver disease were more prevalent in the AMI with marijuana group (all p<0.001) (Table 2).

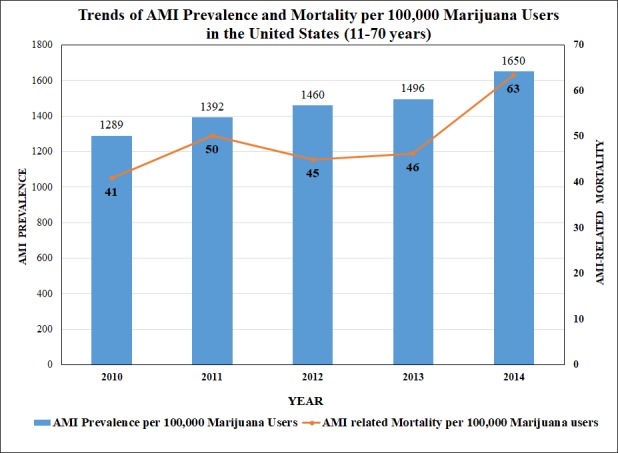

The prevalence trends of dysrhythmias, respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, and congestive heart failure increased by 4.7%, 6.4%, 1.4%, 1.4%, respectively from 2010 to 2014 (p<0.0001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Prevalence Trends of Congestive Heart Failure, Cardiogenic Shock, Dysrhythmias and Respiratory Failure in AMI Patients with Marijuana Use (11-70 years).

Year-wise distribution of baseline demographics, comorbidities, and prevalence of complications in AMI with known marijuana use patients are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Year-wise Baseline Demographics and Comorbidities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients with known Marijuana Use.

| Years | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | P– value* |

| Variables | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Age in years at admission | <0.001 | |||||

| 11-25 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2 | 2.3 | |

| 26-40 | 19.1 | 18.9 | 18.6 | 17.3 | 16.7 | |

| 41-55 | 52.8 | 52.2 | 49.5 | 48.5 | 48.9 | |

| 56-70 | 24.7 | 26.2 | 29.3 | 32.1 | 32.2 | |

| Indicator of Sex | <0.001 | |||||

| Male | 81.1 | 78.5 | 76.6 | 75.8 | 74.5 | |

| Female | 18.9 | 21.5 | 23.4 | 24.2 | 25.5 | |

| Admission Day | <0.001 | |||||

| Monday-Friday | 70.6 | 74.5 | 73.3 | 69.3 | 71 | |

| Saturday-Sunday | 29.4 | 25.5 | 26.7 | 30.7 | 29 | |

| Type of Admissions | <0.001 | |||||

| Non-elective | 93.7 | 93.5 | 95.4 | 96.3 | 94.6 | |

| Elective | 6.3 | 6.5 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 5.4 | |

| Died during hospitalization | <0.018 | |||||

| Did not die | 96.8 | 96.4 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 96.2 | |

| Died | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.8 | |

| Race | <0.001 | |||||

| White | 54.8 | 54.2 | 54 | 55.8 | 57.2 | |

| Black | 33.9 | 33.4 | 33.4 | 33.4 | 31.5 | |

| Hispanic | 7.6 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 6.9 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | |

| Native American | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |

| Other | 2.1 | 3.8 | 4 | 3.4 | 2.9 | |

| Length of stay | <0.001 | |||||

| ≤3 days | 59.8 | 57.5 | 58.1 | 59.3 | 58.9 | |

| 4 to 6 days | 21.3 | 22.4 | 22.8 | 21.5 | 21.2 | |

| 7 to 9 days | 7.6 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 8 | 9.2 | |

| 10 to 12 days | 5.6 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 5 | 4.3 | |

| ≥13 days | 5.8 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.3 | |

| Bed Size of Hospital | <0.001 | |||||

| Small | 8.1 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 9.5 | 14.6 | |

| Medium | 17.8 | 19.5 | 25.1 | 25.6 | 30.2 | |

| Large | 74.2 | 73 | 66.7 | 65 | 55.1 | |

| Location/teaching status of hospital | <0.001 | |||||

| Rural | 9.6 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 4.9 | |

| Urban - non teaching | 35.1 | 38.7 | 34.2 | 34.1 | 22.5 | |

| Urban - teaching | 55.3 | 54.5 | 60.2 | 60.1 | 72.6 | |

| Region of hospital | <0.001 | |||||

| Northeast | 14.6 | 16.8 | 16 | 13.3 | 14.4 | |

| Midwest or North Central | 26 | 24.3 | 26.5 | 28.1 | 29.2 | |

| South | 39.2 | 37.5 | 36.1 | 37.8 | 38.7 | |

| West | 20.3 | 21.4 | 21.4 | 20.8 | 17.7 | |

| Comorbidities# | ||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 25.5 | 24 | 21.8 | 23.3 | 19.8 | <0.001 |

| Deficiency anemias | 10.1 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 11.2 | 13.8 | <0.001 |

| RA/CVD | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4.6 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 20.4 | 20.3 | 22.1 | 23.7 | 24.3 | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 5.6 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 6.7 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 15.3 | 17 | 19.1 | 19 | 20 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 3.1 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 5.7 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 61.6 | 59.2 | 62 | 64.9 | 65 | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2.9 | 3 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 3.3 | 6 | 4 | 4.5 | 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 22.2 | 27.6 | 28.4 | 28.1 | 28.7 | <0.001 |

| Other neurological disorders | 5.8 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 7 | 0.009 |

| Obesity | 12.6 | 14.5 | 15.4 | 15.8 | 17.1 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 6.9 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 0.002 |

| Psychoses | 8.2 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 9.7 | 9.2 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 7.3 | 9.7 | 11.4 | 9.4 | 12.4 | <0.001 |

| Valvular disease | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.001 |

| Weight loss | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 4 | 0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia | 49.1 | 49.4 | 51.1 | 52.6 | 50.1 | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerosis | 5.2 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 7.4 | <0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 11.9 | 11.6 | 13.1 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 0.043 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.006 |

| Thromboembolism | 3 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Previous MI | 13.1 | 10.5 | 12.2 | 14.2 | 13.9 | <0.001 |

| Family history of CAD | 12 | 13.5 | 13.6 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 0.001 |

| Previous PCI | 13.7 | 12.8 | 14.6 | 14.8 | 15.8 | <0.001 |

| History of SCA | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 76.1 | 74.6 | 75.3 | 76.4 | 76.9 | 0.011 |

| Cocaine | 22.1 | 21.3 | 18.3 | 17.5 | 16.8 | <0.001 |

| Amphetamine | 4.6 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Dysrhythmia | 21.3 | 20.8 | 21 | 24.4 | 26 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory Failure | 12.8 | 17.5 | 15 | 15.1 | 17.8 | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 6.1 | 7.6 | 5.8 | 7.6 | 7.4 | <0.001 |

| Septicemia | 3.1 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 6.5 | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 2.3 | 3 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 0.001 |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 3.8 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Vasopressor infusion | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| *Significant P-values ≤ 0.05 at 95 confidence Interval, #Variables are AHRQ Co-morbidity measures | ||||||

| Abbreviations: AIDS – Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, RA/CVD – Rheumatoid Arthritis/ Collagen Vascular Disease, MI – Myocardial Infarction, CAD – Coronary Artery Disease, PCI – Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, CABG – Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting, SCA – Sudden Cardiac Arrest. | ||||||

Odds of AMI incidence in marijuana use

The odds of developing AMI in marijuana users were considerably higher in the male sex (OR=1.507, CI 1.465 - 1.549, p<0.001) and the 56 – 70 years’ age group (OR 11.510, CI 10.678 - 12.406, p<0.001). Drug abuse (OR 16.182, CI 13.824 - 18.942, p<0.001), family history of CAD (OR 4.481, CI 4.315 - 4.652, p<0.001), dyslipidemia (OR 3.275, CI 3.188 - 3.363, p<0.001), cardiomyopathy (OR 2.715, CI 2.612 - 2.823 , p<0.001), previous PCI (OR 2.443, CI 2.344-2.546, p<0.001), smoking (OR 1.695, CI 1.650-1.742, p<0.001), peripheral vascular disorder (OR 1.676, CI 1.538-1.827, p<0.001), and coagulopathy (OR 1.663, CI 1.582-1.749, p <0.001) increased the odds of developing AMI in marijuana users (Table 3). Multivariable analysis showed that marijuana use was a significant risk factor for AMI development when adjusted for age, sex, race (adjusted OR 1.079, 95% CI 1.065-1.093, p<0.001); adjusted for age, female, race, smoking, cocaine abuse (adjusted OR 1.041, 95% CI 1.027-1.054, p<0.001); and also when adjusted for age, female, race, payer status, smoking, cocaine abuse, amphetamine abuse and alcohol abuse (adjusted OR: 1.031, 95% CI: 1.018-1.045, p<0.001). Thus, overall marijuana use was associated with a 3-8% increased the risk of AMI.

Length of stay & total hospital charges

The mean length of stay (days) (4.7±5.9) vs. 5.6±8.0)) and total hospital charges ($76,272.23 vs. $85,702.22) were lower in AMI with marijuana group. The total mean hospital charges were increased from 2010 to 2014 whereas, there was no major change in the mean length of stay from 2010 to 2014. The mean length of stay was almost equivalent in females and males ((4.8±5.7) vs. (4.7±6.0)). All p-values were <0.001.

In-hospital mortality

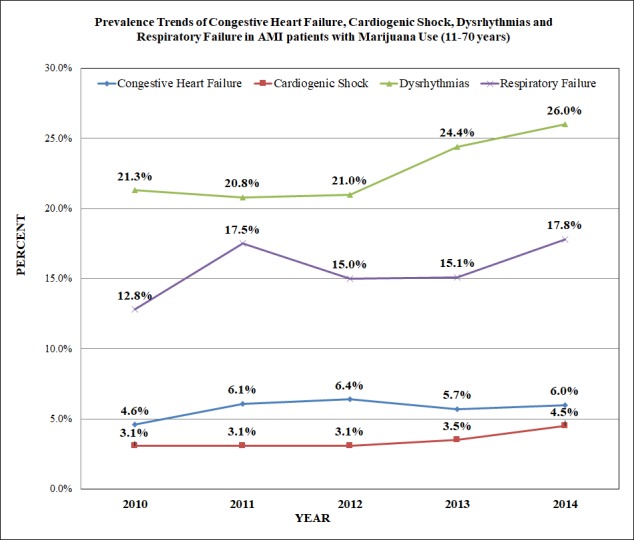

Among all age groups, the 41-55 years’ group showed the highest mortality (46.3%) related to AMI in marijuana users. The mortality in females was found to be higher in White and Black races, whereas Asian and Native American ethnicities showed male predominance. The trend of inpatient mortality pertinent to AMI in marijuana users was significantly increased by 14.7% from 2010 to 2014 (trend p<0.0001) (Figure 1), however; the odds of mortality was not significantly increased in AMI-marijuana group as compared to AMI- non-marijuana group (adjusted OR 0.742, CI 0.693-0.795, p<0.001). The top independent predictors of mortality were respiratory failure (OR 18.895, CI 15.572 – 22.928, p<0.001), cerebrovascular disease (OR 8.977, CI 6.905-11.671, p<0.001), metastatic cancer (OR 7.055, CI 3.482 - 14.294, p<0.001), cardiogenic shock (OR 6.008, CI 4.888 – 7.385, p<0.001), solid tumor without metastasis (OR 3.673, CI 2.054 - 6.570, p<0.001), vasopressor infusion (OR 2.649, CI 1.866-3.761, p<0.001), and hemodialysis (OR 2.342 CI 1.725–3.179, p<0.001). The other predictors are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Multivariate Predictors of Mortality in AMI Patients with known Marijuana Use: Forest plot.

The top independent predictors of mortality were respiratory failure (OR 18.895, CI 15.572 – 22.928, p<0.001), cerebrovascular disease (OR 8.977, CI 6.905-11.671, p<0.001), metastatic cancer (OR 7.055, CI 3.482 - 14.294, p<0.001), cardiogenic shock (OR 6.008, CI 4.888 – 7.385, p<0.001), solid tumor without metastasis (OR 3.673, CI 2.054 - 6.570, p<0.001), vasopressor infusion (OR 2.649, CI 1.866-3.761, p<0.001), and hemodialysis (OR 2.342 CI 1.725–3.179, p<0.001). The other predictors are shown in forest plot.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis, after adjusting the potential confounding factors in different regression models, we reported that use of marijuana linked to amplify the risk of AMI 3- 8% irrespective of the duration of marijuana consumption. The previous study has also shown that risk of AMI is amplified in the individuals who smoke marijuana [4]. There were 13 cases of chest pain and MI which were associated with marijuana smoking [9]. However, the previous studies had the small sample size and did not take the confounding factors into account in the results. Our study utilized the largest inpatient database of the United States which can measure the more accurate risk of AMI in marijuana users. In our study, marijuana use in AMI did not increase overall mortality. Current literature also supports that individuals with long-term use of marijuana may have no increased risk of mortality in the age group of younger than 50 years [10]. According to The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Statistics National Survey [11] for 2006, the substance abuse dependence among adolescents older than 12 years of age and adults was twice more in males than females (12.3% vs. 6.3%). The epidemiology of substance abuse has changed in past few decades, with an increase in girls’ substance abuse [12]. Our study revealed steadily increasing trends (year-wise frequency) of AMI incidence with marijuana use in the female group from 2010 to 2014.

Our study showed that AMI with marijuana group consisted more of younger, male (76.9% vs. 66.0%), African American (33.0% vs. 13.8%) patients compared to the non-marijuana group. The same result has been documented previously [2, 9]. The higher weekend admissions in AMI-marijuana users could be related to recreational substance use more during weekends leading to higher AMI during the same time. The shorter length of stay (LOS) in days and lesser hospital charges in the AMI-marijuana group can be explained due to higher patient disposition against medical advice as compared to the AMI-non marijuana group. In our study, Medicaid is the primary payer in the majority of AMI-marijuana group patients which could be explained by a higher number of low-income patients affected by AMI and forced to have costly substance abuse treatment through Medicaid [8]. The main biological effects of smoking marijuana are mediated by the cannabinoids (CBs) receptors (CB1, CB2) which are located in the central nervous system, heart, adrenal gland, lung, liver [13].

Our study revealed that previous history of MI was documented higher in AMI with marijuana group. In patients with past medical history of coronary artery disease, marijuana appears to produce angina symptoms sooner after exertion as compared to tobacco smoking [14]. The family history CAD which is originally risk factor for AMI was also found to be higher in hospitalized AMI-marijuana group patients. As the previous study has also described depression, psychosis, alcohol abuse, smoking, cocaine abuse, amphetamine abuse and drug abuse were found to be higher with marijuana as compared to non-marijuana users [15]. In addition to the impact of cocaine abuse on stroke [16], an association between cannabinoids use and neurovascular complications have also been reported [17]. In an animal experiment done on rats, THC has shown toxic effects on the mitochondria of the brain by the generation of hydrogen peroxide and reactive oxygen radicals, which is one of the mechanisms involved in stroke in humans [18, 19]. Our study showed increasing year-wise-frequency of dysrhythmias, respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, and congestive heart failure in AMI patients with marijuana use between 2010 to 2014 which could be because of inhaled marijuana generating more carboxyhemoglobin that could interfere in cellular oxygenation [20]. Poor oxygenation to myocardium and lungs could be the explanation for increased cardiovascular diseases with marijuana use [21]. The dysrhythmias after marijuana smoking can be due to increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic activity by tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) [22]. The tachycardia is the most consistent finding after smoking marijuana because of increased sinus node automaticity [23]. Beta-adrenergic stimulation by marijuana induces sinus tachycardia in humans [24]. Cannabis usage can lead to ischemic episodes and tachyarrhythmias [22, 25-27], it can also result in an increase in parasympathetic tone and parasympathetic activity which cause sudden asystolic arrest causing death [28]. The obstructive lung diseases could result from long-time exposure to marijuana smoking [29]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is more common among AMI patients (13.2%) with extended LOS, higher mortality, and more adverse outcomes as compared to those without COPD [30].

This study has a few limitations. Over-reporting or under-reporting the estimated population is possible in this study because of ICD-9 coding errors in an administrative database such as NIS. The time for which patients used marijuana was not specified in the database so we could only measure lifetime risk of AMI in marijuana users. We cannot follow up our study population due to nature of the data. The limitations can be overlooked if the benefits of the large database are weighed against it to analyze marijuana impact on cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

In our study, the lifetime AMI odds were increased up to 8% in recreational marijuana users. Overall odds of mortality were not increased significantly in AMI with marijuana group. However, marijuana users showed higher trends of AMI prevalence and AMI related mortality from 2010 to 2014. It is crucial to assess marijuana-related cardiovascular effects before we can fully explore therapeutic use. We aim to demonstrate the importance of patient history, including recreational drug use, in identifying the etiology of an otherwise unexplained myocardial infarction. The important role of clinicians in educating patients about the potential risks involved in marijuana overuse needs to be emphasized amidst legalization of marijuana use for therapeutic purposes.

Appendices

Table 5. Appendix: ICD-9-CM and CCS Codes Used to Identify Comorbidities, In-Hospital Procedures, and Complications.

| Risk Factors/ Co-morbidity | Source | Codes |

| Smoking | ICD-9 | V15.82, 305.1 |

| Dyslipidemia | CCS | 53 |

| Family history of CAD | ICD-9 | V17.3 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | ICD-9 | 412 |

| Prior PCI | ICD-9 | V45.82 |

| Prior CABG | ICD-9 | V45.81 |

| Atrial fibrillation | ICD-9 | 427.31 |

| Acute respiratory failure | ICD-9 | 518.81, 518.82, 518.84, 799.1, 786.09, 518.4, 518.5 |

| Cardiogenic shock | ICD-9 | 785.51 |

| Atherosclerosis | CCS | 114 |

| Congestive heart failure | CCS | 108 |

| Cardiomyopathy | CCS | 97 |

| History of Sudden Cardiac Arrest | ICD-9 | V12.53 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | CCS | 109 |

| Family History of Stroke | ICD-9 | V17.1 |

| Transient ischemic attack | CCS | 112 |

| Oral contraceptive use | CCS | 176 |

| Thromboembolism | CCS | 118 |

| Hemodialysis | CCS | 58 |

| Motor Vehicle Accident | ICD-9 | E810, E811, E812, E813, E814, E815, E816, E817, E818, E819 |

| Septicemia | CCS | 2 |

| Dressler’s Syndrome | ICD-9 | 411.0 |

| Left Ventricular Failure | ICD-9 | 428.1 |

| Vasopressor Infusion | ICD-9 | 00.17 |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | ICD-9 | 327.23, 780.50, 780.51, 780.53, 780.57, 780.59, or 786.03 |

| Pneumonia | CCS | 122 |

| Cocaine | ICD-9 | 304.20–304.22; 305.60–305.62 |

| Amphetamine | ICD-9 | 304.40–304.42; 305.70–305.72 |

| Alcohol Abuse | ICD-9 | 303.00–303.02; 303.90–303.92; 305.00–305.02 |

| Abbreviations: ICD‐9‐CM= International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; CCS= Clinical Classification Software. | ||

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.World Drug Report 2012. United Nations publication, Sales No E12XI1. [Oct;2017 ];UNODC UNODC. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/WDR-2012.html 2012

- 2.Rockville, MD: [Oct;2017 ]. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardiovascular consequences of marijuana use. Sidney S. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:64–70. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triggering Myocardial Infarction by Marijuana. Mittleman MA, Lewis RA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Muller JE. Circulation. 2001;103:2805–2809. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A rare case of myocardial infarction and ischemia in a cannabis-addicted patient. Kotsalou I, Georgoulias P, Karydas I, Fourlis S, Sioka C, Zoumboulidis A, Demakopoulos N. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32:130–131. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000252218.04088.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marijuana use and mortality. Sidney S, Beck JE, Tekawa IS, Quesenberry CP, Friedman GD. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:585–590. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Database. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD . Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [Oct;2018 ]. March, 2017. Overview of the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trends of Cannabis Use Disorder in the Inpatient: 2002 to 2011. Charilaou P, Agnihotri K, Garcia P, Badheka A, Frenia D, Yegneswaran B. Am J Med. 2017;130:678–687. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acute Myocardial Infarction in a Young Man; Fatal Blow of the Marijuana: A Case Report. Yurtdaş M, Aydın MK. Korean Circ J. 2012;42:641–645. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2012.42.9.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannabis and mortality among young men: a longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Andreasson S, Allebeck P. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2320981. Scand J Soc Med. 1990;18:9–15. doi: 10.1177/140349489001800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-32, DHHS Publication No. SMA 07-4293). Rockville, MD. [Oct;2017 ];Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.asipp.org/documents/2006NSDUH.pdf 2007

- 12.Understanding gender differences in adolescent drug abuse: issues of comorbidity and family functioning. Dakof Dakof, GA GA. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:25–32. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannabinoid receptors in acute and chronic complications of atherosclerosis. Mach F, Montecucco F, Steffens S. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:290–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Effect of marihuana and placebo-marihuana smoking on angina pectoris. Aronow WS, Cassidy J. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:65–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197407112910203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Recreational marijuana use and acute ischemic stroke: A population-based analysis of hospitalized patients in the United States. Rumalla K, Reddy AY, Mittal MK. J Neurol Sci. 2016;364:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Impact of cocaine use on acute ischemic stroke patients: insights from nationwide inpatient sample in the United States. Desai R, Patel U, Rupareliya C, et al. Cureus. 2017;9:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strokes are possible complications of cannabinoids use. Wolff V, Jouanjus E. Epilepsy & Behav. 2017;70:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oxidative stress in ischemic brain damage: mechanisms of cell death and potential molecular targets for neuroprotection. Chen H, Yoshioka H, Kim GS, Jung JE, Okami N, Sakata H, Maier CM, Narasimhan P, Goeders CE, Chan PH. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1505–1517. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tetrahydrocannabinol induces brain mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction and increases oxidative stress: a potential mechanism involved in cannabis-related stroke. Wolff V, Schlagowski AI, Rouyer O, Charles AL, Singh F, Auger C, Schini-Kerth V, Marescaux C, Raul JS, Zoll J, Geny B. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:323706. doi: 10.1155/2015/323706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pharmacology and effects of cannabis: a brief review. Ashton CH. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:101–106. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation: An unknown relationship. Goudis CA. J Cardiol. 2017;69:699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana. Jones RT. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:58–63. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The electrophysiological effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (cannabis) on cardiac conduction in man. Miller RH, Dhingra RC, Kanakis C, Jr. Jr., Amat-y-Leon F, Rosen KM. Am Heart J. 1977;94:740–747. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(77)80215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marihuana smoking. Cardiovascular effects in man and possible mechanisms. Beaconsfield P, Ginsburg J, Rainsbury R. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:209–212. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197208032870501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marijuana as a trigger of cardiovascular events: speculation or scientific certainty? Aryana A, Williams MA. Int J Cardiol. 2007;118:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cannabis as a precipitant of cardiovascular emergencies. Lindsay AC, Foale RA, Warren O, Henry JA. Int J Cardiol. 2005;104:230–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atrial fibrillation associated with marijuana use. Singh GK. Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;21:284. doi: 10.1007/s002460010063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cardiovascular complications induced by cannabis smoking: a case report and review of the literature. Fisher BA, Ghuran A, Vadamalai V, Antonios TF. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:679–680. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.014969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications: a systematic review. Tetrault JM, Crothers K, Moore BA, Mehra R, Concato J, Fiellin DA. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:221–228. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Effect of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease on In-Hospital Mortality and Clinical Outcomes After ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Agarwal M, Agrawal S, Garg L, Garg A, Bhatia N, Kadaria D, Reed G. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:1555–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]