Abstract

Membrane proteins are still heavily underrepresented in the protein data bank (PDB) due to multiple bottlenecks. The typical low abundance of membrane proteins in their natural hosts makes it necessary to overexpress these proteins either in heterologous systems or through in vitro translation/cell-free expression. Heterologous expression of proteins, in turn, leads to multiple obstacles due to the unpredictability of compatibility of the target protein for expression in a given host. The highly hydrophobic and/or amphipathic nature of membrane proteins also leads to challenges in producing a homogeneous, stable, and pure sample for structural studies. Circumventing these hurdles has become possible through introduction of novel protein production protocols; efficient protein isolation and sample preparation methods; and, improvement in hardware and software for structural characterization. Combined, these advances have made the past 10–15 years very exciting and eventful for the field of membrane protein structural biology, with an exponential growth in the number of solved membrane protein structures. In this review, we focus on both the advances and diversity of protein production and purification methods that have allowed this growth in structural knowledge of membrane proteins through X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM).

Keywords: Membrane protein, structural biology, stable isotope enrichment, protein expression and purification, fusion proteins

Introduction

Membrane proteins play crucial roles in a wide variety of cellular functions, including regulation of ion transport across the membrane; sensing and transmitting chemical and electrical signals; mediating cellular attachment; and, controlling membrane lipid composition (von Heijne 2007). The importance of membrane proteins is also highlighted by the facts that they represent ~26% of the human proteome (Fagerberg et al. 2010) and that >50% of currently marketed drugs target this class of proteins (Arinaminpathy et al. 2009; Overington et al. 2006; Yildirim et al. 2007). Membrane proteins can arguably be referred to as the ‘Holy Grail’ in the field of structural biology. Correspondingly, despite their importance and relative prevalence, <2% of the experimentally determined structures in the protein data bank (PDB) are of membrane proteins (mpstruc database (Table 1) relative to the PDB). Characterization of the structure and dynamics of these proteins not only provides insight into their mechanisms of function, but also aids in rational design of novel drugs (Lounnas et al. 2013; Vinothkumar and Henderson 2010).

Table 1.

List of available databases and resources on membrane protein structure.

| Resource description | URL |

|---|---|

| Membrane Proteins of Known 3D Structure (mpstruc database) | http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpstruc/ |

| PDBTM: Protein Data Bank of Transmembrane Proteins | http://pdbtm.enzim.hu/ |

| Membrane Protein Explorer (MPEx) | http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpex/ |

| Membrane Proteins Of Known Structure Determined By NMR | http://www.drorlist.com/nmr/MPNMR.html |

| Detection of Transmembrane Regions by Using 3D Structure of Proteins (TMDET) | http://tmdet.enzim.hu/ |

| IUPHAR Database | http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/ |

| Transporter Classification Database | http://www.tcdb.org/ |

| Experimentally Solved GPCR Structures (GPCR-exp) | http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/GPCR-EXP/ |

| GPCR Database (GPCRDB) | http://www.gpcr.org/7tm/ |

| Plant Membrane Protein Database | http://aramemnon.uni-koeln.de/ |

| Human Membrane Protein Analysis System | http://fcode.kaist.ac.kr/hmpas/ |

Over the past few decades, X-ray diffraction (XRD) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) have been the predominant techniques for atomic resolution structural determination, with electron crystallography and microscopy increasing in prevalence primarily through advances in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) instrumentation and methodologies. By 2000, there were 26 (9 by NMR) unique integral membrane structures in the PDB (Bowie 2000). Studies to this point often relied upon proteins found naturally at high abundance, meaning that a relatively small number of proteins were accessible to structural studies. Notable early examples include bacteriorhodopsin (Henderson and Unwin 1975) and light harvesting complex proteins (Deisenhofer et al. 1984); channels such as the β-barrel porins (Weiss et al. 1990) or the α-helical aquaporin (Cheng et al. 1997; Li et al. 1997; Walz et al. 1997) and KcsA potassium channel (Doyle et al. 1998); respiratory enzymes (Tsukihara et al. 1995); the G-protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin (Palczewski et al. 2000); and, the sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase (Toyoshima et al. 2000).

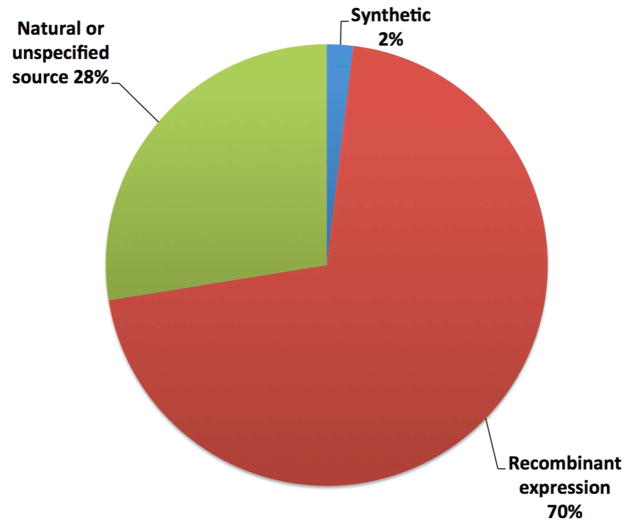

In the past 15 years, improvements in methods for protein expression, solubilization, and stabilization have led to a tremendous increase in the number of solved membrane protein structures (Pedersen and Nissen 2015). As of now, there are ~587 unique membrane protein structures solved, including >130 by NMR spectroscopy (see Table 1 for useful databases). Notably, in contrast to early studies relying upon natural sources, at least 70% of currently available structures in the PDBTM (Kozma et al. 2013) are of recombinantly expressed proteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Source of protein for all 2631 experimentally solved membrane protein structures currently available in the PDBTM. (Numbers based upon annotations in the PDB file headers, with “unspecified source” based only on the PDB file header.)

The clear disparity in the degree of structural information available for membrane proteins relative to soluble proteins stems mainly from their hydrophobicity and low levels of natural abundance, which produce obstacles in the path of studying membrane proteins at all steps from protein expression through to sample preparation. This review focuses on the significant progress made in expression and purification of membrane proteins, relating this to considerations in sample preparation for structural characterization of membrane proteins using XRD, NMR or cryo-EM, with an underlying goal of comparing and contrasting a wide variety of successful strategies.

Expression hosts

Structural studies typically require milligram quantities of protein. Given that membrane proteins are generally scarce in their natural environment, heterologous expression of these proteins has become the predominant method (Figure 1) to obtain enough protein for characterization (Bill et al. 2011). However, heterologous expression in the host of choice is not always feasible due to the often toxic nature of a membrane protein upon overexpression in that host (Bernaudat et al. 2011). In addition, discrepancies in the levels of expression from one membrane protein to the next are not yet completely understood (Grisshammer 2006). Thus, it is not currently possible to predict the degree of toxicity of a target protein, making its relative expression in a given host still a matter of trial and error. Correspondingly, a variety of expression hosts have been used successfully for expression of target membrane protein. These differ in their ability to carry out post-translational modifications (PTM), in level of expression, and in sensitivity to modification of culture conditions, which can dictate the selection of one host over the other (summarized in Table 2). In this section, we briefly discuss the advantages and limitations of the most commonly used expressions systems, with Figure 2 demonstrating the relative usage of each for membrane proteins.

Table 2.

Pros and cons of various membrane protein expression systems.

| Expression system | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | High expression levels Low cost Simple culture conditions Rapid growth Scaleable Simple transformation protocols Many parameters can be altered to optimise expression Least expensive for NMR-active isotope labelling Engineered strains can help alleviate the problems with disulfide bond formation (Shuffle and Origami) and codon bias (Rossetta and CodonPlus RIL/RP) |

Inefficient disulfide bond formation Poor folding of proteins in the cytoplasm sometimes leading to inclusion body formation Codon usage different to eukatyotes Minimal post-translational modifications (systems available to allow some modifications) Endotoxin present |

| Saccharaomyces cerevisiae | Good expression levels Choice of secreted or cellular expression Low cost Simple culture conditions Scaleable Able to perform most eukaryotic post-translational modifications Efficient protein folding Endotoxin-free |

Likely lower expression than with Pichia pastoris Secretion likely lower than with Pichia pastoris Glycosylation differs from mammalian cells Tendancy to hyperglycosylate proteins N-glycan structures considered allergenic |

| Pichia pastoris | High expression levels Low cost Simple culture conditions Relatively rapid growth Scaleable Choice of secreted or intracellular expression Extensive post-translational modification of proteins Relatively inexpensive NMR-active isotope labeling Efficient protein folding N-glycosylation more similar to higher eukaryotes than with Saccharomyces cerevisiae Endotoxin-free |

Use of methanol as inducer is a safety (fire) hazard at scale Glycosylation differs from mammalian cells |

| Baculovirus-infected insect cells | Good expression levels Relatively rapid growth Efficient protein folding Moderately scaleable Extensive post-translational modification of proteins Glycosylation more like mammalian cells Relatively easy enzymatic deglycosylation Endotoxin-free |

Expensive culture media Large volumes of virus needed on scale-up Inefficient processing of pro-peptides in secretory pathway Glycosylation still different to mammalian cells Viral infection leads to cell lysis and potential degradation of expressed proteins |

| Mammalian cells | Good expression levels Moderately scaleable Suspension-adapted cells facilitate scale-up Efficient protein folding All post-translational modifications Endotoxin-free |

Expensive culture media Complex growth requirements |

| Cell-free protein production |

E.coli, wheat germ, insect and mammalian systems commercially available Scaleable Protein synthesis conditions can be manipulated Can readily incorporate non-natural amino acids Easy to vary isotope labeling patterns for NMR spectroscopy Can use PCR products as template Endotoxin-free |

Limited post-translational modifications Relatively expensive (however, protein yield per unit volume may overcome this) |

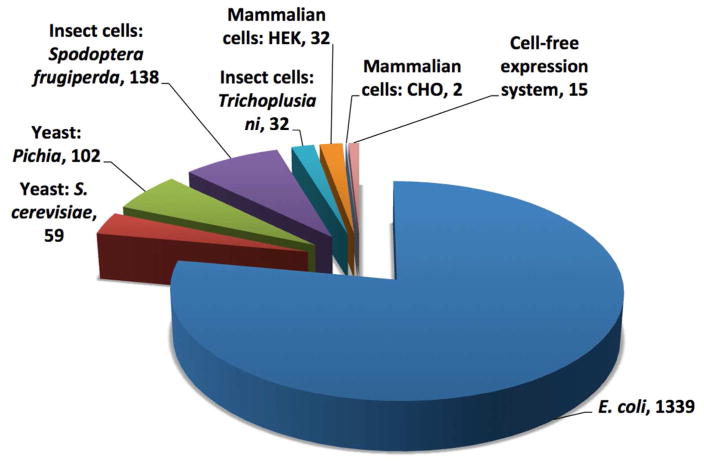

Figure 2.

Expression system employed for all solved membrane protein structures produced by recombinant expression currently available in the PDBTM. (Numbers based upon annotations in the PDB file headers; hence, the total of 1719 is slightly lower than the 1855 implied by Figure 1.)

Escherichia coli

E. coli is the most widely used host system for expression of recombinant proteins, with membrane proteins being no exception (Figure 2), for five main reasons. (i) E. coli has fast growth kinetics with a doubling time of 20 min in optimal conditions (Sezonov et al. 2007). This reduces the time required for expression of the protein of interest (POI). (ii) Cells can be grown to high density to achieve very high protein production (Shiloach and Fass 2005). (iii) Growth medium is inexpensive and can be manipulated without a significant loss in yield, enabling enrichment with stable isotopes for NMR (Marley et al. 2001; Tyler et al. 2005) and selenomethionine for XRD (Sreenath et al. 2005; Stols et al. 2004). (iv) Extensive knowledge of genetics, physiology, and metabolism has enabled intelligent genetic manipulations to produce strains with specific advantages (e.g.,(Andersen et al. 2013; Sorensen and Mortensen 2005; Studier 1991; Wagner et al. 2008)). (v) An abundance of expression vectors (https://www.embl.de/pepcore/pepcore_services/cloning/choice_vector/ecoli/index.html) enables easy incorporation of desired properties in the plasmid vector.

T7 RNA polymerase (T7RNAP) from Enterobacteria phage λ is often used to drive recombinant protein production in E. coli (Studier 1991). T7RNAP exclusively recognizes the T7 promoter and synthesizes RNA several times faster than E. coli RNA polymerase with fewer observed incomplete transcripts due to premature termination, allowing higher protein yield (Iost et al. 1992). Typically, T7RNAP is employed under control of the lac operon, where addition of isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) induces expression of T7RNAP and subsequently enables overexpression of the POI (Studier 1991). Since E. coli can grow on minimal medium, rich medium can be replaced with a medium containing isotope-enriched precursors or amino acids before inducing expression, enabling cost effective production of proteins amenable to heteronuclear NMR characterization (Marley et al. 2001).

Recently, auto-induction of membrane protein expression has been suggested to be more effective than traditional T7RNAP IPTG-induced expression (Gordon et al. 2008). In this method, protein production is induced by lactose in the medium, which only occurs upon the depletion of metabolites such as glucose. Although the auto-induction protocol seems to provide an edge over the traditional IPTG induction protocol, its cost-effectiveness is somewhat compromised in producing isotope-enriched proteins for NMR (Tyler et al. 2005). For additional background, the reader is referred to detailed reviews of various aspects of recombinant protein expression using E. coli expression systems (Baneyx 1999; Makrides 1996; Rosano and Ceccarelli 2014; Sorensen and Mortensen 2005; Stevens 2000).

The prokaryotic E. coli system also has many limitations. Specifically, this organism often lacks the essential lipids, molecular chaperons, and machinery for PTMs required for correct membrane insertion and eukaryotic protein folding. It is important to note that efforts have been made to overcome these barriers by methods such as codon-optimization (Burgess-Brown et al. 2008); addition of fusion tags for a variety of purposes (detailed below); and, co-translation/induction of post-translational machineries to facilitate protein folding (de Marco et al. 2005). However, use of E. coli still leads to many challenges in order to be an ideal expression system for a membrane POI. For further detail, Miroux and co-workers (Hattab et al. 2015) have recently provided an extensive analysis of the impact of E. coli expression systems in the field of membrane protein structural characterization.

Yeast

Yeast are next in popularity to E. coli (Figure 2) and exhibit many similar advantages for heterologous expression. For example, yeast also have rapid growth rate, the ability to be grown to high density, well-studied genetics, and readily available advanced tools for genetic manipulation. However, yeast cells have the added advantage of being capable of performing various eukaryotic PTMs. These modifications include proteolytic processing of signal peptide sequences; disulfide-bond formation; prenylation; phosphorylation; acylation; and, certain types of O- and N-linked glycosylation that may be essential for activity, correct folding, and membrane insertion of proteins (Boer et al. 2007). It is important to note that glycosylation patterns vary between different yeast strains, with some strains engineered to produce more uniform and human-like glycosylation patterns (Hamilton et al. 2003; Hamilton et al. 2006; Vervecken et al. 2007). These factors make yeast an inexpensive and efficient alternative to prokaryotic expression systems for production of membrane proteins. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia Pastoris (Pichia) are the most commonly used species for expression of membrane proteins (Bornert et al. 2012; Joubert et al. 2010). Schizosaccharomyce pombe is less frequently used, but sometimes outperforms other yeast species in expression of mammalian membrane proteins (Sander et al. 1994b; Takegawa et al. 2009).

Using S. cerevisiae, a model eukaryote with a long history of study, comes with a few perks. These include a completely sequenced genome, a variety of genetic manipulation tools, and a large number of available strains available for expression of eukaryotic membrane proteins (Drew et al. 2008; Goffeau et al. 1996; Li et al. 2009; Winzeler et al. 1999). In comparison to other strains of yeast, protocols are available for high-throughput expression of membrane proteins (Newstead et al. 2007). The ability to carry out in vivo homologous recombination also makes S. cerevisiae an attractive host to produce membrane protein mutants in a high-throughput fashion to optimize expression for downstream applications (Ito et al. 2008).

Despite these advantages, the methylotrophic yeast Pichia has been the most frequently and successfully applied membrane protein expression host among all the yeast strains (Figure 2). A Pichia expression system was first released for academic use in 1993, following which there has been an exponential increase in the knowledgebase and the number of membrane proteins expressed using this system (Cregg et al. 2000; Ramon and Marin 2011). A key physiological trait of Pichia is its strong preference for respiratory growth, facilitating culturing at higher densities than fermentative yeast. Its methylotrophic nature also means that it can derive energy by metabolism of methanol using enzymes such as alcohol oxidase (AOX) and dihydroxyacetone synthase (DHAS) (Stewart et al. 2001). Since the promoters of methanol utilization pathways are very efficient and tightly regulated, they are most commonly used for expression of heterologous proteins (Hollenberg and Gellissen 1997). Using this system, very high expression yields have been achieved for membrane proteins (e.g., 90 mg·L−1 for human aquaporin (Nyblom et al. 2007)). Similar to E. coli, Pichia can grow on minimal medium that can be modified to produce isotope-enriched protein required for structural characterization using NMR (Denton et al. 1998; van den Burg et al. 2001; Wood and Komives 1999). Although the cost of production of an isotope-enriched protein may be higher compared to E. coli, Pichia is still a very attractive alternate host for production of isotope-enriched proteins that cannot be efficiently produced in E. coli (Clark et al. 2015).

Baculovirus/insect cells

Third in popularity (Figure 2), and providing many advantages, are baculovirus/insect cell expression systems. In comparison to other virus-based methodologies, baculovirus is safe due to its inability to infect mammals. Similarly to other eukaryotic expression systems, baculovirus/insect cell expression of heterologous genes typically permits proper protein folding as a consequence of PTMs that are often identical to those that occur in higher eukaryotes (Shi and Jarvis 2007). Cell cultures from the insects Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9, Sf21) and Trichoplusia ni (Hi5) infected by the baculovirus Autographa californica multi-nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) are the most commonly used systems for membrane protein expression (Hitchman et al. 2009). As in all expression systems, the heterologous expression of proteins varies in yield when expressed in different types of insect cells (Unger and Peleg 2012).

A typically employed commercially available system for production of recombinant baculovirus for expression of proteins in insect cells is the BAC-to-BAC® (Invitrogen by life technologies, Waltham, MA, USA) system. In this protocol, the target gene is sub-cloned into the pFastBac vector, which is then transformed into DH10Bac E. coli competent cells harbouring a baculovirus shuttle vector (bacmid) with a transposon site and a helper plasmid. Transposition of the target gene onto the bacmid gives rise to a recombinant bacmid that can be purified and used for production of recombinant virus that can be later used for infection of insect cells for testing protein expression. This entire process takes approximately 3–4 week to reach the stage of testing protein expression. Recently, a faster and more convenient method employing transient transfection was designed for a rapid screening of membrane protein expression (Chen et al. 2013).

To date, baculovirus-insect cell expression has given the highest number of eukaryotic membrane proteins for structural characterization (He et al. 2014). It is, however, relatively expensive to produce proteins by this method in comparison to the systems discussed earlier. Moreover, due to complex metabolism and inability to grow in minimal medium, it is currently prohibitively expensive to produce isotope-enriched proteins for structural characterization by NMR (Gossert and Jahnke 2012; Sitarska et al. 2015). Notably, an economical approach has recently been put forward for expression of isotope-enriched proteins using a homemade isotope-enriched yeast extract (Opitz et al. 2015). Given the reported success of this system, it is highly appealing to devise strategies to reduce cost over currently available protocols.

Mammalian cells

Membrane proteins that require specific PTMs and subcellular environments for proper folding and activity are often impossible to produce in functional form by prokaryotic or lower eukaryotic systems. Interestingly, the difficulty in competent protein production has been stated to not be proportional to the number of transmembrane segments or to the size of the protein; rather, it appears to arise from the complexity of folding process for the protein in question (Tate 2001). It is likely that a combination of various factors decides the fate of protein expression in a specific expression host. Therefore, mammalian cell lines seem to be an obvious choice to obtain functional mammalian proteins. However, these systems also have drawbacks.

One of the main drawbacks with mammalian cell systems is that levels of expression relative to the systems already introduced are typically very low, even under conditions of induced overexpression, making it prohibitively expensive to produce sufficient protein for structural studies (Andrell and Tate 2013). Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO), human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293), baby hamster kidney cells (BHK-21) and monkey kidney fibroblast cells (COS-7) are the most commonly used cell lines for expression (Andrell and Tate 2013). These different cell lines can vary significantly in terms of expression level depending on the POI, requiring individual optimization for each POI.

Mammalian cell line-based expression can also be performed either by transient transfection or by making stable cell lines. Transient transfection can be either carried out using recombinant viruses (Dukkipati et al. 2008; Hassaine et al. 2006; Matrai et al. 2010) or using chemical agents (Geisse and Fux 2009). Although more time consuming, stable transfection provides a means of producing heterologous proteins with high reproducibility and expression level (Camponova et al. 2007; Chelikani et al. 2006). It is also important to note that there are engineered cell lines that can have beneficial outcome depending on the POI. For example, the HEK293S-TetR cell line, with a tetracycline-inducible expression system (Reeves et al. 2002b), allowed crystallization of a mutant form of rhodopsin that could not be expressed in a constitutive expression system, likely due to the toxic nature of the POI. Cell lines such as CHO Lec.3.2.8.1 (Stanley 1989), HEK293S GnTI(−) (Reeves et al. 2002a), and HEK 293S Lec36 (Crispin et al. 2009) have mutations that lead to modified levels of N-glycosylation and/or decreased complexity, which can lead to improved crystallization (Deupi et al. 2012). To date, due to complex metabolism and prohibitively expensive expression media, a very limited number of proteins have been expressed using mammalian expression system with isotope-enrichment, illustrating the current challenge of applying this class of expression system for NMR (Sastry et al. 2012).

Cell-free expression systems

In all of the conventional cell-based expression systems, the focus is on overexpression, which often results in improper protein folding and membrane insertion. In the case of membrane proteins, overexpression also frequently leads to formation of protein aggregates, destabilization of cellular membranes, and interaction with host metabolic machinery leading to cytotoxicity (Klammt et al. 2006). Therefore, cell-free expression systems (also referred to as in vitro translation systems) were developed to bypass the complexities and sensitivities inherent in dealing with living cells (Nirenberg and Matthaei 1961). In recent years, cell-free expression has gained in popularity for the expression of membrane proteins.

Typically, a cell-free expression system is an open system enabling in vitro protein translation with the help of translation machineries provided by the cell lysates from various organisms (Schwarz et al. 2008). A major attractive feature of cell-free systems for membrane protein expression is the ability to implement a carefully chosen folding environment. This allows for better control over the driving forces of membrane protein folding such as lipid composition (Phillips et al. 2009); hydrophobic mismatch (Cybulski and de Mendoza 2011); membrane lateral pressure and curvature (Botelho et al. 2006; Marsh 2007); membrane elasticity (Lundbaek 2006; Lundbaek et al. 2010); and, cholesterol content (Chini and Parenti 2009; Pucadyil and Chattopadhyay 2006). Cell-free expression systems exhibit supressed interconversion of amino acids, enabling a wide range of isotope-enrichment patterns that can be exploited in various NMR approaches to solve the signal overlap problem that is common in membrane protein structural characterization (Junge et al. 2011; Ozawa et al. 2006; Parker et al. 2004; Reckel et al. 2011). Cell-free systems also allow production of proteins with Stereo-Array Isotope Labeling (SAIL) (Kainosho et al. 2006). SAIL is a method of producing proteins with amino acids having certain stereospecific patterns of isotopes optimal for protein NMR analysis, particularly for structural characterization of large proteins by NMR (Takeda et al. 2008; Tonelli et al. 2011).

Currently, several types of cell-free system are available, based upon extracts from different sources, such as: E. coli (Schwarz et al. 2007), wheat germ (Harbers 2014), rabbit reticulocyte (Anastasina et al. 2014), Spodoptera frugiperda (Ezure et al. 2014), CHO cells (Brodel et al. 2014), mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Zeenko et al. 2008), and the HeLa cell line (Mikami et al. 2006). Among these, E. coli lysate is currently the most widely, and successfully, applied cell-free expression medium. Variations have been developed, such as the Protein synthesis Using Recombinant Elements (PURE) system (Shimizu et al. 2001) containing a minimal set of purified elements required for the translation reaction, and the Cytomim system (Jewett et al. 2008) where, besides the E. coli cell extract, inverted inner membrane vesicles from E. coli are also added. Recently, the PURE system has been optimized for rapid production of high quantities of functional membrane proteins by adding liposomes to the reaction mixture (Kuruma and Ueda 2015). Although relatively expensive in terms of the required isotope-enriched precursors, cell-free expression is a very attractive technique for production of isotope-enriched proteins for structural characterization by NMR. It should also be noted that although production of properly folded membrane proteins has not yet been streamlined in cell-free expression systems, this class of expression has a great deal of potential, especially when it comes to production of membrane proteins for NMR.

Use of fusion proteins - advantages and limitations

As stated earlier, recombinant proteins can be difficult to express and purify. One of the most common strategies to solve this problem is to fuse a proteinaceous tag to the protein of interest (POI), as detailed in Table 3. Such additions have been shown to improve the yield of the target proteins in E. coli through increased expression (Kefala et al. 2007; Leviatan et al. 2010; Pandey et al. 2014), allowing for greater potential yield. Another strategy to increase the yield of membrane proteins and other difficult-to-express proteins is to specifically target them to inclusion bodies using insoluble fusion partners, shielding them from proteolytic degradation and preventing other perturbations to cell function (Hwang et al. 2014). Some tags increase solubility (Butt et al. 2005; Marblestone et al. 2006) to improve handling during subsequent purification and/or to enhance purification through affinity chromatography methods (Hochuli et al. 1988). Tags may also be extremely valuable to facilitate crystallization for XRD (Engel et al. 2002; Cherezov et al. 2007).

Table 3.

Properties and applications of commonly used fusion tags sorted by class of use in alphabetical order.

| Tag (Reference(s)) | Size* | Organism | Tag placement | Use | Used in membrane protein expression in [expression system]? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calmodulin binding domain (Vaillancourt et al. 2000) | 26 aa | Mammalian | N- or C-terminal | Purification | Yes (Pestov and Rydstrom 2007) [E. coli] |

| Cellulose binding module (Tomme et al. 1998) | 4–20 kDa | Synthetic | N- or C-terminal | Purification | Yes (Maurice et al. 2003) [fish] |

| c-Myc (Ellison and Hochstrasser 1991) | 11 aa | H. sapien | N- or C-terminal | Purification | Yes (Sarramegna et al. 2002) [yeast] |

| Dock (dockerin domain) (Kamezaki et al. 2010) | 22 aa | C. josui | N-or C-terminal | Purification | No |

| FLAG (Munro and Pelham 1984) | 8 aa | Synthetic | N- or C-terminal | Purification | Yes (Quick and Wright 2002) [E. coli] |

| HA (hemagglutinin) (Field et al. 1988) | 9 aa | Influenza Virus | N- or C-terminal | Purification | Yes (Gao et al. 2015) [insect] |

| IMPACTTM (intein-mediated purification with chitin binding domain) (Chong et al. 1997) | 51 aa | B. ciruculans, Pyrococcus sp., S. cerevisiae | N- or C-terminal | Purification† | No |

| Poly-His (Hochuli et al. 1988; Kohno et al. 1998) | 6–12 aa | Synthetic | N or C-terminal | Purification | Yes (Park et al. 2012a) [E. coli] |

| S (S protein of RNase A) (Kim and Raines 1993) | 15 aa | Mammalian | N- or C-terminal | Purification | No |

| Strep II (Schmidt et al. 1996) | 8 aa | S. avidinii | N or C-terminal | Purification | Yes (Rahman et al. 2007) [E. coli] |

| Fh8 (Fasciolahepatica 8-kDa antigen) (Costa et al. 2013a; Costa et al. 2013b) | 69 aa | F. hepatica | N-terminal | Purification & solubility | No |

| GST (glutathione S-transferase) (Smith and Johnson 1988) | 211 aa | S. japonicum | N-terminal | Purification & solubility | Yes (Park et al. 2012a) [E. coli] |

| HaloTag (Mutated dehalogenase) (Ohana et al. 2009) | ~300 aa | Rhodococcus sp. | N-terminal | Purification & solubility | Yes (Suzuki et al. 2013) [mammlian] |

| MBP (maltose binding protein) (di Guana et al. 1988; Pryor and Leiting 1997) | 396 aa | E. coli | N- or C-terminal | Purification & solubility | Yes (Chaudhary et al. 2011) [E. coli] |

| T7 gene10 (Olins et al. 1988) | 260 aa | Bacteriophage T7 | N-terminal | Purification & solubility | No |

| Ubiquitin (Kohno et al. 1998) | 76 aa | S. cerevisiae | N-terminal | Purification & solubility | Yes (Bird et al. 2015) [E. coli] |

| Acidic proteins (MsyB and YjgD) (Zou et al. 2008) | 124, 138 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| AK (adenylate kinase) (Liu et al. 2015) | 362 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | Yes (Londesborough et al. 2014) [yeast] |

| ArsC (Stress-responsive arsenate reductase) (Song et al. 2011) | 141 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| CaBP (Calcium-binding protein) (Reddi et al. 2002) | 134 aa | E. histolya | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| Crr (glucose-specific phosphotransferase enzyme IIA component) (Han et al. 2007a) | 169 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| CysQ (3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphatase) (Lee et al. 2014) | 266 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| EDA (KDPG aldolase) (Kang et al. 2015) | 213 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| EspA (E. coli secreted protein A) (Cheng et al. 2010) | 192 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| GB1 (IgG domain of B1 of protein G) (Huth et al. 1997; Kumar et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2001) | 56 aa | Streptococcus sp. | N-terminal | Solubility | Yes (Kumar et al. 2012) [E. coli] |

| IF2-domain I (N-terminal fragment of translation initiation factor IF2) (Sørensen et al. 2003) | 158 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| Mocr (Monomeric bacteriophage T7 0.3 protein) (DelProposto et al. 2009) | 117 aa | Bacteriophage T7 | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| NusA (N-utilization substance) (Davis et al. 1999) | 495 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | Yes (Goehring et al. 2014) [mammalian] |

| PotD (spermidine/putrescine-binding periplasmic protein) (Han et al. 2007a) | 348 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| RpoA, S, D (RNA polymerase subunits) (Ahn et al. 2007; Zou et al. 2008) | 329, 330, 613 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| Skp (Seventeen kDa protein) (Chatterjee and Esposito 2006) | 161 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| SlyD (FKBP-type peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase) (Han et al. 2007b) | 196 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| SNUT (Solubility enhancing ubiquitous tag) (Caswell et al. 2010) | 147 aa | S. aureus | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| SUMO (small ubiquitin modified protein) (Zuo et al. 2005a) | 100 aa | H. sapiens | N-terminal | Solubility | Yes (Zuo et al. 2005b) [E. coli] |

| T7PK (Phage T7 protein kinase) (Chatterjee and Esposito 2006) | ~240 aa | Bacteriophage T7 | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| Trx (Thioredoxin) (LaVallie et al. 1993) | 109 aa | E. coli | N- or C-terminal | Solubility | Yes (Yeliseev et al. 2007) [E. coli] |

| Tsf (elongation factor Ts) (Han et al. 2007b) | 283 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility | No |

| GlpF (the glycerol-conducting channel protein) (Neophytou et al. 2007) | 281 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Inner membrane insertion | Yes (Neophytou et al. 2007) [E. coli] |

| OmpA signal sequence (Tiralongo and Maggioni 2011) | 21 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Inner membrane insertion | Yes (Tiralongo and Maggioni 2011) [E. coli] |

| S. cerevisiae α-factor signal sequence (Weiss et al. 1995) | 89 aa | S. cerevisiae | N-terminal | Plasma membrane insertion | Yes (Weiss et al. 1995)[yeast] |

| Yeast STE2 receptor signal sequence (King et al. 1990; LaVallie et al. 1993) | 24 aa | S. cerevisiae | N-terminal | Plasma membrane insertion | Yes (Ficca et al. 1995; King et al. 1990; Sander et al. 1994a)[yeast] |

| Lpp-OmpA (Lpp signal peptide + OmpA) (Francisco et al. 1992) | 142 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Outer membrane display | Yes# [E. coli] |

| Ice nucleation protein (Inp) (Jung et al. 1998) | 114 kDa | P. syringae | N-terminal | Outer membrane display/insertion | Yes# (Yim et al. 2010) |

| Ecotin (E. coli trypsin inhibitor) (Malik et al. 2006) | 162 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Solubility & periplasm/media secretion | No |

| ZZ (IgG repeat domain ZZ of Protein A) (Löwenadler et al. 1987; Rondahl et al. 1992) | 116 aa | S. aureus | N- and C-terminal | Solubility & periplasm/media secretion | Yes (Nizard et al. 2001) [mammalian] |

| Cell-CD (cellulase catalytic domain) (Gao et al. 2015) | 20, 375 aa | Bacillus sp. | N-terminal | Periplasm/media secretion | No |

| Cex (exoglucanase) (Hasenwinkle et al. 1997) | 41 aa | C. fimi | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | No |

| DsbA (disulfide oxidoreductase A) (Soares et al. 2003) | 19 aa | E. coli | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | Yes (Jappelli et al. 2014) [E. coli] |

| Exl/Enx (endoxylanase) (Jeong and Lee 2000, 2001) | 12, or 28 aa | Bacillus sp. | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | No |

| LamB (λ receptor protein) (Pratap and Dikshit 1998) | 25 aa | E. coli | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | Yes# |

| LTB (heat-labile enterotoxin subunit B) (Sanchez et al. 1988) | 21 aa | E. coli | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | No |

| Outer membrane protein (OmpC, F) (Becker and Hsiung 1986) | 21, 22 aa | E. coli | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | Yes# [E. coli] |

| OmpT (protease VII) (Kurokawa et al. 2001) | 20 aa | E. coli | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | Yes# [E. coli] |

| PhoA (alkaline phosphatase) (Xu et al. 2002) | 21 aa | E. coli | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | Yes (Kaderbhai and Kaderbhai 1996) [E. coli] |

| PelB (pectate lyase B) (Better et al. 1993) | 22 aa | E. carotov | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | Yes (Jappelli et al. 2014) [E. coli] |

| SpA (S. aureus Protein A) (Abrahmsén et al. 1986) | 280 | S. aureus | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Purification& periplasm/media secretion | Yes (Hansson et al. 1995) [E. coli] |

| SthII (heat stable enterotoxin II) (Qiu et al. 1998) | 23 aa | E. coli | N-terminal (signal sequence) | Periplasm/media secretion | No |

| AT rich gene tags (PS, T7, AT, SER, H, G, R) (Haberstock et al. 2012; Pandey et al. 2014) | 8, 11, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6 aa | Derived from various species | 5′-end of mRNA | Expression enhancement | Yes (Haberstock et al. 2012; Pandey et al. 2014) [E. coli] |

| HmBRI/D94N (mutated bacteriorhodopsin (BR) (Hsu et al. 2013) | 250 aa | H. marismortui | N-terminal | Expression enhancement | Yes (Hsu et al. 2013) [E. coli] |

| Mistic (Kefala et al. 2007; Marino et al. 2015) | 110 aa | B. subtilis | N-terminal | Expression enhancement | Yes (Kefala et al. 2007; Marino et al. 2015) [E. coli] |

| YaiN (regulator of frmRAB operon) (Leviatan et al. 2010) | 98 aa | E. coli | N- or C-terminal | Expression enhancement | Yes (Leviatan et al. 2010) [E. coli] |

| YbeL (Leviatan et al. 2010) | 120 aa | E. coli | N- or C-terminal | Expression enhancement | Yes (Leviatan et al. 2010) [E. coli] |

| EDDIE (N-terminal autoprotease NPRO) (Achmuller et al. 2007) | 168 aa | Classical swine fever virus | N-terminal | Inclusion body targeting | No |

| KSI (ketosteroid isomerase) (Kuliopulos and Walsh 1994) | 14 kDa | P. testosteroni | N-terminal | Inclusion body targeting | Yes (Chun et al. 2012) [E. coli] |

| Outer membrane protein FΔSP (OmpF missing signal peptide) | 142 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Inclusion body targeting | Yes (Su et al. 2013) [E. coli] |

| PagPΔSP (palmitoyltransferase missing the signal peptide) (Hwang et al. 2012) | 161 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Inclusion body targeting | No |

| PaP3.30 (ORF 30) (Rao et al. 2004) | 162 aa | P. aeruginosa bacteriophage Pap3 | N-terminal | Inclusion body targeting | No |

| PurF (N-terminal of polypeptide F4) (Lee et al. 2000) | 152 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Inclusion body targeting | No |

| TAF12 HFD (histone folding domain of human transcription factor) (Vidovic et al. 2009) | 72 kDa | H. sapiens | N-terminal | Inclusion body targeting | No |

| TrpΔLE (deletion of a part of TrpL from TrpE operon) (Cook et al. 2011) | 17 aa | E. coli | N-terminal | Inclusion body targeting | Yes (Cook et al. 2011) [E. coli] |

| BRIL (thermostabilized apocytochrome b562) (Chun et al. 2012) | 10.9 kDa | H. sapiens | Intermolecular | Stabilization & crystallization | Yes (Chun et al. 2012) [insect] |

| T4 lysozyme (Engel et al. 2002) | 15.9 kDa | Bacteriophage T4 | Intermolecular | Stabilization & crystallization | Yes (Engel et al. 2002) [E. coli] & (Cherezov et al. 2007; Chun et al. 2012; Granier et al. 2012; Kruse et al. 2012) [insect] |

aa: amino acids

intein-mediated removal of chitin binding domain (single step purification, no protease-mediated removal of tag)

Given that the tags are derived from membrane proteins, they have inherently been used for membrane protein expression

Note: tags may not function as specified depending on the effect of POI on the fusion protein.

In the case of membrane proteins, targeted localization of an aggregate-prone and hydrophobic POI to the expression medium or periplasm has also been shown to improve yield (Better et al. 1993). Periplasmic targeting may also be employed to produce disulfide-bonded recombinant proteins (de Marco 2009). In some instances, inner membrane targeting of the POI through fusion tags has proven successful for membrane POI overexpression (Neophytou et al. 2007; Tiralongo and Maggioni 2011). Localization to the outer membrane may also be targeted Jung, 1998 #280; Francisco, 1992 #281}, although this is typically used for surface display of soluble proteins (van Bloois et al. 2011). Fusion tags composed of native yeast signal sequences are also used to target the membrane in yeast expression systems (King et al. 1990; Weiss et al. 1995).

The benefits of fusion tags may potentially be both additive and complementary, meaning that they are often fused together in various arrangements to improve yield (Costa et al. 2013a; Liu et al. 2015; Pryor and Leiting 1997), including for isotope-enriched membrane proteins for NMR (Kohno et al. 1998; Leviatan et al. 2010). Given the difficulties in expressing mammalian (and non-mammalian) membrane proteins in heterologous systems such as E. coli, use of fusion tags is usually essential in producing sufficient quantities for structural studies.

Although fusion tags have many advantages, the design of fusion tag-POI constructs demand careful planning with consideration of the exact construct in question. One property of the tag itself that calls for careful selection is its size. Larger tags tend to impose a heavy metabolic burden on the host system, which increases with the complexity of the amino acid composition (Table 3). Use of large tags can also lead to interactions between the fusion tag and the POI. This phenomenon can be favourable for aggregate-prone proteins, since larger tags such as NusA inhibit the aggregation and promote solubility (Davis et al. 1999). However, these interactions will likely interfere with structure and/or activity (Majtan and Kraus 2012; Sabaty et al. 2013; Singh et al. 2013). This leads to another factor that must be carefully optimized: the length of the linker between the tag and the POI. This linker region must be long enough to prevent unfavourable tag-target interaction and to allow for proper folding of the target protein (Raran-Kurussi and Waugh 2012). Unfortunately, the linker region can also impede structural characterization, since its flexibility can interfere with crystallization. A solution for many of these issues is removal of the tag through various means, as detailed below. An additional factor with direct relation to selection of tag(s) is the optimal purification protocol, where success can vary in the presence or absence of various salts, chelating agents, and/or detergents. This is discussed in greater detail below.

In short, use of fusion tags can cause a great deal of grief due to the complexities, required optimization of conditions, and, nearly limitless number of possible arrangements for fusion tags. However, the advantages afforded are often significant. Given their utility in protein expression upon optimized design, fusion tags are likely to remain a key factor in membrane protein production.

Tag removal strategies

Although fusion tags are highly useful, they often must be removed from the POI prior to structural studies, since they can affect both structure and function of the target protein. This leads to an additional layer of complexity in recombinant protein production and is often the bottleneck in such a procedure. As in the choice of the tags themselves (Table 3), there is a wide variety of choice for tag removal strategies. Possibilities include protease-mediated cleavage, self-cleavage, chemical cleavage, and in vivo cleavage. Each of these methods may take advantage of a number of different reagents/proteases to cleave the tag (Table 4 lists a variety of commercially available proteases that have been employed with membrane proteins). With the ongoing introduction of new reagents and proteases, the already wide array of potential tag-target fusion designs continues to increase (Marino et al. 2012).

Table 4.

Properties of commercially available proteases reported for cleavage of fusion tags from membrane proteins in alphabetical order. Note that references include both key primary literature around protease and examples of usage for membrane proteins.

| Proteasea (Reference(s)) | Cleavage site (at “|”) | Size | Location of tag | pH range | Chaotrope sensitivity | Salt sensitivity | Temperature range (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterokinase (Choi et al. 2001; Goncharuk et al. 2011) | DDDDK| | 31 kDa | N-terminal | 7–8 | 4–37 | ||

| Factor Xa (Jenny et al. 2003; Periasamy et al. 2013) | IEGR| | 43 kDa | N- or C-terminal | 6–9 | ≤ 0.25 M Urea ≤ 0.25 M GnCl ≤1% Triton X- 100 ≤ 0.001% SDS |

≤ 0.25 M NaCl or imidazole | 4–37 |

| Rhinovirus 3C protease (PreScission) (Clark et al. 2010; Cordingley et al. 1990) | LEVLFQ|GP | 46 kDa | N- or C- terminal | 7–8 | ≤ 1% Triton, Tween, NP40 | ≤ 0.5 M NaCl | 5–15 |

| Subtilisin BPN (Profinity eXact) (Huang et al. 2012) | EEDKLFKAL| (C-terminus of propeptide) | 27.8 kDa | N-terminal | 7.2 | ≤ 2 M Urea (no GnCl) | ≤3 M NaCH3CO O (no Cl−) | 4–30 |

| SUMO protease (Li and Hochstrasser 1999; Malakhov et al. 2004; Zuo et al. 2005a) | GG| (C-terminus of SUMO) | 72 kDa | N- terminal | 7–9 | ≤ 2 M Urea | ≤ 0.3 M NaCl ≤ 0.15 M imidazole |

4–30 |

| TEV (tobacco etch virus) (Kapust and Waugh 2000; Parks et al. 1994) | ExxYxQ|(G/S) | 27 kDa | N- or C- terminal | 6–8.5 | ≤ 2 M Urea | ≤ 0.1 M | 4–37 |

| Thrombin (Jenny et al. 2003; Jidenko et al. 2006) | LVPR|G | 37 kDa | N- or C- terminal | 5–10 | ≤ 0.1 M Urea | ≤ 0.15 M | 4–37 |

Cleavage conditions and chemical compatibility based on commercial protocols/handbooks: Sigma/Aldrich - TEV, thrombin and enterokinase; NEB – Factor Xa; Invitrogen – SUMO; BioRad – Subtilisin BPN; GE Healthcare – 3C.

Further complicating this issue, the efficiency of tag removal can vary dramatically between different target proteins. For example, steric hindrance or unfavourable residues at cleavage sites can hamper protease-mediated tag removal. This may be circumvented by use of a different protease with different active site requirements; lengthening of the linker region; use of a smaller tag; or, through use of chemical cleavage methods involving reagents such as cyanogen bromide (CNBr) or 2-nitro-5-thiocyanatobenzoic acid (NTCB), which cleave C-terminal to Met and Cys, respectively (Crimmins et al. 2005). In addition, different methods present different difficulties. For example, off-target cleavage can occur from proteases that recognize specific short amino acid motifs. Some proteases also leave residual amino acids on the target protein, thus increasing the protein size (Table 4) and, potentially, perturbing function. The removal of a tag can also yield improperly folded or disrupted target protein structures due to protein aggregation and precipitation under cleavage conditions. Thus, cleavage conditions require optimization through trial and error and can be highly time-consuming.

Following optimized cleavage, purification of the POI away from the cleaved tag is usually accomplished in three-steps: i) initial purification of the fusion protein; ii) subsequent in vitro removal of the tag; and, iii) separation of the tag and protease from the target protein. As discussed in detail below, each purification step has components that require careful selection and optimization, and again can be very time-consuming. To avoid some of these limitations, a variety of methods have been developed. One example is the IMPACT™ system (Chong et al. 1997), which uses inducible self-cleaving tags to increase yield by decreasing the loss of protein during multiple purification steps and also reduces the overall time required for purification. These tags rely on inteins, an internal peptide segment that can self-excise upon activation and join the remaining portions (exteins), to produce two independent products. Another method is in vivo cleavage, also referred to as controlled intracellular processing (CIP) (Kapust and Waugh 2000). In CIP, the tagged protein and protease are co-expressed, but their expression is independent. Upon its induction, the protease can proteolytically cleave the tag from the POI intracellularly, resulting in considerable savings in time and cost. Innovations such as these in tag removal may allow for more rapid and optimal production of difficult membrane proteins for structural study and ongoing developments have great promise for future studies.

Considerations for membrane protein purification

One of the first factors to consider after overexpression of the POI is its localization. This is essential, since localization must be factored into selection of the initial purification method. For example, use of pelB tag can lead to localization of the protein to the medium or periplasm, which is mostly void of intracellular protein, allowing for simpler down-stream purification. Some proteins tend to aggregate into inclusion bodies, either with or without tags, and may require more stringent methods of solubilization prior to initial purification (Carrio and Villaverde 2002). Localization to inclusion bodies can also be highly beneficial, assuming the POI can be refolded, since this may greatly simplify downstream purification (Fan et al. 1996). Depending upon the host, membrane proteins can even be localized to the host cell membrane, which requires purification of cell membrane and subsequent solubilization prior to purification. Thus, identifying or manipulating (through tags) the localization of the target protein is an important step as it can dictate the method of purification.

The next logical consideration in purification is the solubilization process. Similar to tag removal methods, there are various methods of solubilization. The relative effectiveness of these methods is difficult to predict; therefore, trial and error is often involved to identify the most optimal and compatible method. Solubilization of membrane proteins typically relies either upon detergents, which coat exposed hydrophobic regions of the protein to allow solubilization, or chaotropic agents, which disrupt hydrogen bonds and decrease the hydrophobic effect, in turn favouring protein disaggregation. If possible, maintaining protein structure throughout the solubilization and purification process can be advantageous, as the process of refolding a denatured protein can prove to be extremely challenging (Booth 2003). However, membrane proteins have a tendency to aggregate without detergents or chaotropic agents, making subsequent purification more difficult (Smith 2011). Thus, it must be decided at this step whether it is essential to maintain protein structure (and potentially function) throughout the process, as this can severely limit the scope of available solubilization and purification methods.

Purification techniques can be grouped into two categories: techniques that exploit the intrinsic properties of the protein, and techniques that require the use of a fusion tag. In practice, the purification process for many membrane proteins involves several techniques performed sequentially to achieve the desired purity (Park et al. 2008; Whiteman et al. 2014; Yun et al. 2015). Perhaps the most important consideration in choosing a purification technique is the compatibility of the solubilizing detergent or chaotropic agent with the purification technique of choice. For example, the charge state of a detergent may interfere with any technique that exploits the isoelectric point of the protein. Alternatively, detergent micelles bound to proteins may inhibit interaction in any affinity-based purification technique.

Following these considerations, fusion tag-based purification is the most popular method for initial purification of membrane proteins. Of all the fusion tags, polyhistidine tags are the most commonly used, enabling immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC). IMAC is a versatile technique as it can be used for proteins solubilized using ionic or nonionic detergents alongside chaotropic agents (Bornhorst and Falke 2000). Detergent-solubilized membrane proteins are also susceptible to degradation by proteases, making the use of protease inhibitors necessary. It should be noted that protease inhibitors such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) that work by chelation of metal ions are incompatible with IMAC, even at moderately high concentrations. Many alternative fusion tag purification (Table 3) techniques can be applied to overcome this issue. Unfortunately, those techniques may also be hindered by the use of detergents required to solubilize the POI. For example, the interaction between the Strep-II tag and its affinity purification resin is often weakened by the presence of detergent micelles. Repeating the tag sequence is one strategy to counter these negative effects and increase affinity (Yeliseev et al. 2007).

Proteins can also be purified on the basis of differences in isoelectric point using ion exchange chromatography (IEC). Generally, ionic detergents cannot be used for solubilization of membrane proteins when employing this technique, which limits the number of possible detergent choices for solubilization. While using non-ionic or zwitterionic detergents, this method can also be applied to separate the protein-detergent complexes from the homogeneous detergent clusters (Seddon et al. 2004).

Reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) separates proteins based upon predominantly hydrophobicity and, to some degree, size, providing a purification technique particularly useful for small membrane proteins (Langelaan et al. 2013; Lee et al. 1996). The use of RP-HPLC requires careful consideration, as detergents cannot be used, and membrane proteins will be in a denatured state. This could cause large membrane proteins to exhibit a broad elution profile or to elute as a series of separate populations due to adoption of different conformations.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC), or gel filtration chromatography, separates proteins based on hydrodynamic volume, in some instances corresponding directly to molecular weight (Kunji et al. 2008). Sephadex, Superose, Superdex and Sephacryl are the most commonly used matrices for purification of membrane proteins by SEC. In comparison to other purification techniques, it has a lower resolution due to its inability to differentiate between species of similar hydrodynamic volume (Kunji et al. 2008). Therefore, it is often coupled with other methods to obtain the desired purity of the membrane protein. It is also critical to recognize that the apparent molecular weight of the protein will increase if it is bound to detergent micelle(s), complicating purification.

Detailed resources, e.g. (Arnold and Linke 2007; GE Healthcare 2007; Von Jagow et al. 1994), are available to aid in designing purification protocols for membrane proteins. In short, when using any protein purification technique, one must consider the downstream effects that the chosen strategy may have on both the final structure and functional state of the protein.

Rapid screening methods for membrane protein expression

In the case of membrane proteins, it is often challenging to identify a suitable expression host, optimize the level of protein expression and obtain a monodisperse sample for structural characterization. Successful high-level expression of functional membrane proteins for structure determination often requires evaluation of multiple versions of the POI obtained using strategies including additions and deletions in the N- and C- terminus, mutants with variations in natural sequence, and/or different fusion proteins. Therefore, methods for screening of expression of multiple membrane proteins in parallel are very useful. Fusing green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the POI is one of the most commonly used methods to gauge expression levels without purifying the protein (Chalfie et al. 1994). Coupling SEC with fluorescence-detection enables screening for both expression and homogeneity of the produced membrane protein sample. Fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography (FSEC) experiments using a GFP-tagged POI to screen for expression level and monodispersity has been used for various proteins produced using different expression systems (Bird et al. 2015; Chaudhary et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2013; Goehring et al. 2014; Kawate and Gouaux 2006). Proper implementations of such high-throughput methods have great potential to significantly enhance structural biology efforts for membrane proteins.

Considerations in sample preparation for structural studies

If the objective is X-ray crystallography, then crystallization conditions must be optimized to obtain well-diffracting, sufficiently large crystals upon successful purification of a folded membrane protein. For initial crystallization trials, various crystallization conditions are usually screened using the vapour diffusion method (Delmar et al. 2015). Conditions leading to crystal formation are then subsequently optimized. Screening systems such as MemStart, MemGold and MemSys are specifically designed for membrane protein crystallization trials (Carpenter et al. 2008; Newstead et al. 2008). In order to solubilize a membrane POI for crystallization, protein detergent complexes, bicelles, or lipid cubic phases (LPCs) may be employed.

In the case of protein-detergent complexes (the most commonly employed phase for membrane protein crystallization (Loll 2014)), an important point to keep in mind is that the membrane protein must be solubilized with a detergent that forms micelles that are relatively small in size as compared to the size of the protein itself. This is due to the fact that large micelles may inhibit protein crystallization (Prive 2007). The most successfully and frequently applied detergents for membrane protein crystallization (Loll 2014; Prive 2007) are alkyl glycosides such as n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG), n-nonyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (NG), n-decyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DM), n-undecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (UM), n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM), and the cyclohexyl maltoside (CYMAL) family of detergents alongside the maltose-neopentyl glycol (MNG) amphiphiles; N,N-dimethyldodecylamine-N-oxide (LDAO); and, octyltetraoxyethylene (C8E4) and other polyoxyethylenes.

Alternatively, bicelles (disk or Swiss cheese-like structures comprising a mix of long chain lipids and short chain lipids or detergents (Poulos et al. 2015; Prosser et al. 2006)) may be employed for crystallization. Most frequently, the lipid 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) is mixed with 3-([3-Cholamidopropyl]dimethylammonio)-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPSO) or an analogue of CHAPSO (Poulos et al. 2015). Although relatively unpopular and, arguably, underutilized at present (Loll 2014), bicelles provide the potential to maintain a bilayer environment throughout the crystallization process and offer some advantages in sample handling and manipulation over detergent-protein complexes and the LCP. Methodologies and considerations for bicelle-based crystallization and analysis are comprehensively covered in (Poulos et al. 2015).

The lipid cubic phase (LCP), also referred to as in meso conditions, is an alternative method of protein crystallization that has gained popularity and shown great success in membrane protein crystallization in the past decade (Loll 2014). For in meso crystallization, the standard protocol involves homogenizing the purified protein–detergent complex with a monoacylglycerol (MAG) like monoolein, and then adding the precipitant to initialize crystallization. This is comprehensively reviewed in (Caffrey 2015).

Reduction of protein dynamics is another very important prerequisite in obtaining well-diffracting crystals. There are various factors that can be modified to reduce protein dynamics, including optimization of buffers, detergents, bicelle components, or LCP constituents employed during crystallization. In addition, fusion proteins or antibodies have been beneficial in crystallization. Although the previous section discussed fusion tag removal, retaining the tag has been fundamental for decreased dynamics and improving crystallization for many proteins studied by XRD. For example, T4 lysozyme fusion (Engel et al. 2002) was instrumental in the crystallization of many GPCRs including β2-adrenergic receptor (Cherezov et al. 2007), δ-opioid receptor (Granier et al. 2012), and M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (Kruse et al. 2012). Antibodies, antibody fragments, or nanobodies have also been used to decrease dynamics to facilitate crystallization. In the case of GPCRs, use of nanobodies (as G-protein mimics) allowed for crystallization of GPCRs in the active conformation to provide valuable information on receptor activation and subsequent G-protein binding (Kruse et al. 2013; Rasmussen et al. 2011). Also, mutating residues with a high degree of dynamics also yielded well-diffracting crystals, as seen in β1-adrenergic receptor (Serrano-Vega et al. 2008), neurotensin receptor (Shibata et al. 2009), and adenosine A(2A) receptor (Lebon et al. 2011). Lastly, post-expression modification of proteins has been helpful in promoting crystallization of membrane proteins. Such modifications including limited proteolysis to remove flexible regions (Doyle et al. 1998) and deglycosylation to remove heterogenous glycosylation (Sui et al. 2000) are frequently employed, as reviewed in (Columbus 2015). Thus, screening different crystallization conditions, antibodies and fusion proteins, and mutations/modifications for decreased dynamics are common and fundamental steps in crystallization (Loll 2014; Prive 2007; Serrano-Vega et al. 2008).

Notably, recent advancements in XRD have been afforded by the introduction of free-electron lasers. This has allowed a significant step forward in structural characterization of membrane proteins, making possible the collection of diffraction data from micron- or submicron-scale crystals alongside time-resolved studies of protein dynamics on an ultrafast time scale (Neutze et al. 2015). This has clear potential for extremely high impact in the field, but is also not a routinely available technique.

NMR is a very versatile technique for atomic-level studies of biomolecular structure and dynamics. Membrane proteins may be characterized in environments amenable to either solution- or solid-state NMR methods. These methods differ in their requirement for isotropic tumbling of the nuclei being probed, with large molecules or complexes (>100 kDa) being extremely challenging to characterize by, if at all amenable to, solution-state NMR (Nietlispach and Gautier 2011). NMR allows study of membrane proteins in their native environment (Brown and Ladizhansky 2015; Murray et al. 2013) or, following reconstitution, in native-like environments, including membrane-mimetics such as organic solvent mixtures (Schwaiger et al. 1998), micelles (Arora et al. 2001), bicelles (Prosser et al. 2006), nanodiscs (Gluck et al. 2009; Hagn et al. 2013), and bilayers (Das et al. 2013). Based on the size of the reconstituted assembly of the membrane protein, either solution-state or solid-state approaches are used for their characterization. For solution-state NMR, approaches such as transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY) (Pervushin et al. 1997) and specific-isotope labeling schemes (Tugarinov et al. 2002) have been used to extend the use of solution-state NMR for larger protein assemblies. These approaches rely upon exploitation of differential/optimal relaxation properties, and have also been exploited to study both structure and dynamics of integral membrane proteins (Gautier et al. 2010; Hwang and Kay 2005). Solution-state NMR is a very powerful technique to study appropriately sized membrane protein samples in mimetics such as an organic solvent mixture, detergent micelles, isotropic bicelles and monodisperse nanodiscs,

For both solution-state NMR and XRD, it is of great importance that the monodispersity and stability of the reconstituted membrane protein (whether in micelles, bicelles, or another environment) be determined prior to attempting structure determination. For XRD, maintaining soluble monodispersed protein is crucial for successful crystallization while for solution-state NMR a polydisperse sample will unduly confound what is likely an already challenging resonance assignment process. SEC may be used to confirm homogeneity of a purified/solubilized POI, monodispersity and oligomeric state of the POI, and as such is frequently used as an analytical technique to validate sample integrity (Kunji et al. 2008), rather than “just” for purification as discussed above. Hydrodynamics techniques, such as dynamic light scattering (Neale et al. 2013), sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifuation (Ebel 2011), or pulsed-field gradient diffusion NMR (Liebau et al. 2015), are highly valuable alternatives or corroborative techniques for SEC-based confirmation of sample mondispersity.

Study of membrane proteins in a native environment typically requires different types of lipids, leading to larger protein-lipid complexes such as non-isotropic bicelles, macrodiscs, or bilayers that are not compatible with solution-state NMR. In the case of these samples, where transverse relaxation is typically extremely rapid while longitudinal relaxation may be extremely slow, one must resort to solid-state NMR approaches. Recent advance in solid-state NMR have enabled structural characterization of membrane proteins in environments very close to the native membranes, as very nicely reviewed in (Opella 2015) and (Judge et al. 2015). Solid-state NMR has strong potential for characterization of both structure and dynamics of membrane proteins, and is still being actively developed.

Cryo-EM is a method which is rapidly growing in popularity in the field of membrane proteins. In cryo-EM, atomic-level structures can be determined either by electron crystallography, in which electron diffraction from 2D crystals afford high-resolution, or single particle analysis, where a 3D structure is determined through computational reconstruction of 2D images from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of many individual macromolecules in identical or similar conformations but stochastic orientation. Cryo-EM presents a number of practical difficulties to overcome for near-atomic resolution structure calculations. These include sample dehydration under vacuum, radiation damage by the electron beam, and poor electron scattering by biological macromolecules. To get around first two issues, preparations of biological cryo-EM samples involve cryogen-mediated trapping of samples in a thin layer of noncubic amorphous or vitrified ice; thus, giving the name cryo-EM. This step allows for preservation of specimen at near-native, hydrated environment.

Although cryo-EM was once limited by low-resolution arising from a poor signal to noise ratio, current state of the art cryo-EM can characterize protein structures at a single digit Å level and is pushing towards smaller and smaller proteins (Smith and Rubinstein 2014). To date, the best resolution of 1.9 Å (on par with the best XRD structures) was observed for the membrane protein aquaporin using the electron crystallography technique (Gonen et al. 2005). Recently, the single particle reconstruction technique was used to solve the structure of the 170 kDa human γ-secretase to 3.4 Å, an elusive target of XRD, and the smallest protein solved by cryo-EM thus far (Bai et al. 2015). Improved microscope technology (Zhou and Chiu 1993); detector technology (Campbell et al. 2012; Ruskin et al. 2013), and computational resources and image processing strategies (Shigematsu and Sigworth 2013) have all been instrumental in the increased resolution now possible.

In particular, cryo-EM is phenomenally suited to characterization of large molecular weight complexes. It is important to note that such characterization often relies upon structures of some or all of the components making up the complex previously determined by XRD or NMR in order to produce an atomic model. The γ-secretase structure mentioned above, for example, used the XRD-derived domain structures to model the 170 kDa complex (Bai et al. 2015). The role of cryo-EM in understanding of membrane protein structure will only increase as technology continues to advance. Comprehensive overviews of cryo-EM are provided by (Binshtein and Ohi 2015; Kuhlbrandt 2014; Liao et al. 2014).

Deciding between methods of membrane protein structure determination

If a protein is relatively small (<50 kDa), and amenable to isotopic enrichment through expression in an appropriate host and subsequent solubilization, then solution-state NMR may be preferable as this provides the potential to gain insight into conformational dynamics and ligand binding mechanisms. The structure and dynamics of the heptahelical protein sensory rhodopsin II, for example, proved amenable to structural and dynamic characterization in both detergent micelles and in bicelles (Gautier et al. 2010). Probing of specific regions of β2-adrenergic receptor was made possible by labeling with NMR-active 19F Trp (Manglik et al. 2015) or 13C Met (Nygaard et al. 2013), allowing elucidation of the effects of agonists, antagonists, and G-proteins upon the conformational equilibrium of the receptor.

If a protein is larger than ~50 kDa, solution-state NMR becomes very difficult (although by no means impossible) for the reasons outlined earlier. Larger proteins amenable to isotope enrichment may then be good targets for solid-state NMR study, allowing solubilization in a bilayer setting and study of both dynamic and more rigid portions of the protein. Nice recent examples of state-of-the-art capabilities of solid-state NMR include the backbone structure of the GPCR CXCR1 (Park et al. 2012b) alongside characterization of heptahelical Anabaena sensory rhodopsin structure (Wang et al. 2013) and dynamics (Good et al. 2014) in lipid bilayers.

If the protein is ordered in its nature or can be forced into an ordered structure through use of tags, antibodies, or mutagenesis, then both cryo-EM (2D crystal) and XRD (3D crystal) may be desirable. In particular, XRD allows for relatively rapid determination of structures of unknown novel POIs, as is manifest in its near monopoly in the field of protein structure characterization for many years. Given that XRD is dependent on crystallization, any dynamic regions of the POI will unfortunately not be visible. Ideally, specific regions of this nature could be probed either in isolation or in the full protein by NMR spectroscopy, assuming that POI is amenable to the conditions stated above.

In the case of a relatively large POI that contains domains of solved structure, cryo-EM can be greatly advantageous compared to NMR and XRD in elucidating various conformations simultaneously in a single sample set. A recent example was the differentiation between multiple conformations of V-ATPases, providing valuable insights in the mechanism of ATPase activity (Zhao et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2015). However, given that cryo-EM does not always present high-resolution images, one could argue that cryo-EM may be most optimal as a complementary technique. For reference, Table 5 provides an overview of pros and cons of each the techniques discussed. Exploiting the advantages of each technique under proper conditions will further our understanding of membrane protein structure and dynamics.

Table 5.

Pros and cons of XRD, solution- and solid-state NMR, and cryo-EM.

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| XRD | Get entire 3D structure at atomic-level resolution if well-diffracting Single model visualization (easy interpretation) Large protein structure determination possible Largely automated Fast data acquisition |

Stable and well-diffracting crystals required (long screening time) Cannot resolve dynamic regions Unnatural/non-physiological conditions Potential artefacts during crystallization |

| Solution-state NMR | Does not require crystals Ability to probe dynamics, conformational equilibrium, protein folding, intra- and intermolecular interactions, reaction kinetics (many different experiments observing various nuclei) Potential for near-native (if not native) conditions/environment |

Optimization of conditions to solubilize samples May require concentrated samples (potential aggregation) Isotope-labeled samples, often requiring multiple variations (costly) Data assignment is time-consuming Produces an ensemble of possible structures (data interpretation less straightforward than single model) Limited to relatively small proteins |

| Solid-state NMR | Does not require crystals Ability to probe dynamics, conformational equilibrium, protein folding, intra- and intermolecular interactions, reaction kinetics (many different experiments observing various nuclei) Large protein structure determination possible Native or near-native environments quite readily employed |

Optimization of sample conditions Isotope-labeled samples (costly) Data assignment is time-consuming Produces an ensemble of possible structures |

| Cryo-EM | Mostly physiological or native in its condition Do not require crystals Can resolve different conformations in an ensemble (heterogeneous and dynamic samples) Large protein structure and complex determination possible |

May not achieve atomic resolution Highly technical sample preparation procedure Require large data set (costly and lengthy acquisition) Electron beam can damage samples and cause particle movement |

Concluding Remarks

The past 15 years have been truly remarkable for the field of membrane protein structural biology, with tremendous expansion in protein production, sample preparation, and experimental approaches. As an example, this growth has provided structural insight into 31 unique members of one of the most sought after class of membrane proteins, the G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Chrencik et al. 2015; Dore et al. 2014; Park et al. 2012b; Srivastava et al. 2014; Tautermann 2014; Yin et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2015a; Zhang et al. 2015b). However, this set of 31 GPCRs represents only a fraction of all GPCRs (~800 in the human genome; (Fredriksson et al. 2003)), with many receptors remaining uncharacterized due to a lack of high throughput and generalized methods for membrane protein production. As has been highlighted throughout this review, even with all of the recent advances, determining optimal, often protein-specific, conditions for membrane protein production and characterization still tends to heavily rely upon trial and error and remains an extremely time-consuming task.

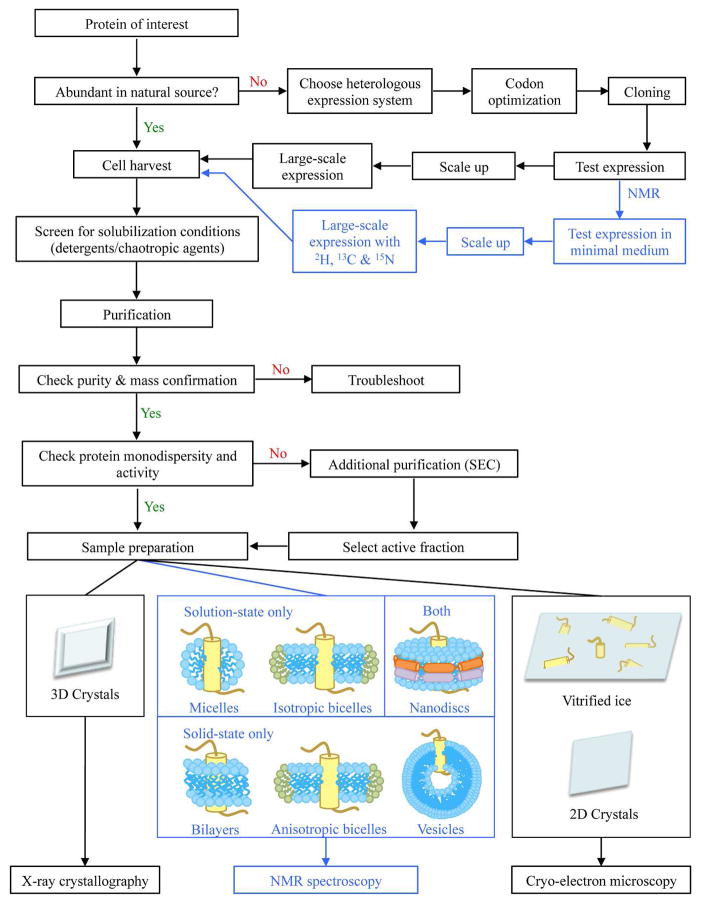

In this review, we have tried to encapsulate the advancements that have allowed the recent growth in structural knowledge of membrane proteins, with an emphasis on heterologous production, subsequent purification, and screening of conditions for structure characterization (Figure 3). To summarize, E. coli tends to be the most cost-effective (and popular, Figure 2) host for membrane protein production. However, due to the lack of eukaryotic PTM machineries, membrane proteins tend to aggregate, misfold, and impair cell viability. In these cases, use of yeast, baculovirus, or mammalian system may be beneficial; however, yields may be substantially lower and cost may be prohibitive. Cell-free expression systems are, therefore, perhaps the most attractive alternative, given the number of different configurations possible. Regardless of expression system, new fusion tags, proteolytic, and chemical cleavage strategies continue to provide new routes to enhanced expression and purification. Unfortunately, until more streamlined methods to screen membrane protein production and purification protocols are developed, obtaining the required quantity of well-folded and functional protein will remain the bottleneck in membrane protein structural biology.

Figure 3.

Flowchart outlining various optimization steps allowing for structural characterization of membrane proteins by XRD, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-EM.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant (MOP-111138 to J.K.R.); a Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation (NSHRF) Scotia Support Grant (to J.K.R.); and, a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (to X.Q.L.). AP was supported by the Beatrice Hunter Cancer Research Institute with funds provided by the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce and the Harvey Graham Cancer Research Fund as part of The Terry Fox Strategic Health Research Training Program in Cancer Research at CIHR; KS is supported by an Alexander Graham Bell Canadian Graduate Scholarship from NSERC; and, JKR is supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award.

References

- Abrahmsén L, Moks T, Nilsson B, Uhlén M. Secretion of heterologous gene products to the culture medium of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14(18):7487–7500. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.18.7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achmuller C, Kaar W, Ahrer K, Wechner P, Hahn R, Werther F, Schmidinger H, Cserjan-Puschmann M, Clementschitsch F, Striedner G, Bayer K, Jungbauer A, Auer B. N(pro) fusion technology to produce proteins with authentic N termini in E. coli. Nat Methods. 2007;4(12):1037–1043. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn KY, Song JA, Han KY, Park JS, Seo HS, Lee J. Heterologous protein expression using a novel stress-responsive protein of E. coli RpoA as fusion expression partner. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2007;41(6–7):859–866. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasina M, Terenin I, Butcher SJ, Kainov DE. A technique to increase protein yield in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate translation system. Biotechniques. 2014;56(1):36–39. doi: 10.2144/000114125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]