Abstract

Background

Understanding the social determinants underlying health disparities benefits from a mixed-methods, participatory research approach.

Objectives

Photovoice was used in a research project seeking to identify and validate existing data and models used to address socio-spatial determinants of health in at-risk neighborhoods.

Methods

High-risk neighborhoods were identified using geospatial models of pre-identified social determinants of health. Students living within these neighborhoods were trained in Photovoice, and asked to take pictures of elements that influence their neighborhood’s health and to create narratives explaining the photographs.

Results

Students took 300 photographs showing elements that they perceived affected community health. Negative factors included poor pedestrian access, inadequate property maintenance, pollution, and evidence of gangs, criminal activity, and vagrancy. Positive features included public service infrastructure and outdoor recreation. Photovoice data confirmed and contextualized the geospatial models while building community awareness and capacity.

Conclusions

Photovoice can be a useful research tool for building community capacity and validating quantitative data describing social determinants of health.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research Photovoice, youth, Hispanic, community, health

For most of its 225-year history, Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, was a quintessential southern city with little international immigration. Now, this city is in the midst of a significant demographic transformation. As one of the United States’ pre-emerging immigrant gateways, Charlotte is experiencing rapid immigrant population growth. Between 1980 and 2010, Mecklenburg County’s foreign-born population grew from 2.3% to 13.5%, with half of this population originating from Latin America.1

Although Hispanic immigrants have a wide variety of social and economic backgrounds, many experience linguistic, economic, cultural, legal, structural, and/or transportation barriers to accessing the community resources they need to build new lives. This is particularly true for access to medical services; research has shown that Hispanic immigrant health is influenced by many of these factors. A mixed-methods research approach is needed to fully understand this community’s utilization of and access to healthcare services because quantitative data derived from government and hospital sources provides only a partial view. Triangulating quantitative data with qualitative findings captures what is happening in the community at the local level and illuminates people’s everyday experiences accessing services. Adding a participatory component to the research further facilitates community capacity building.2–9

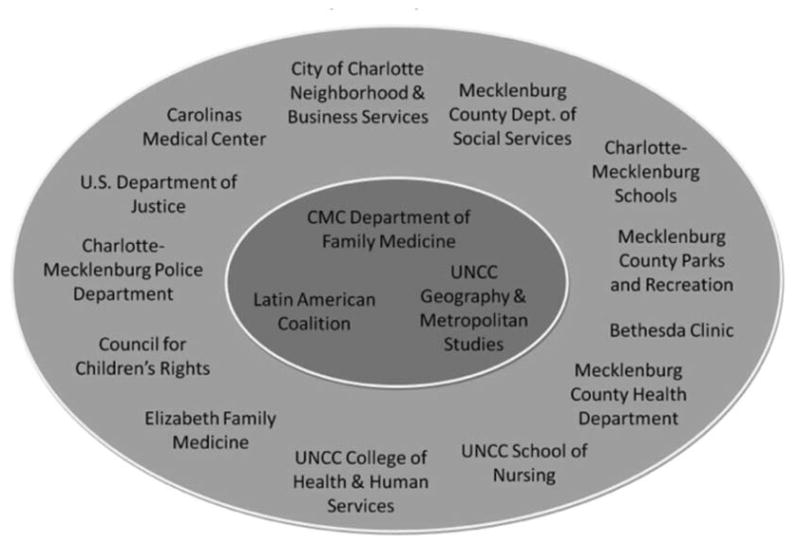

The Mecklenburg Area Partnership for Primary-Care Research (MAPPR) is a collaboration of healthcare providers, researchers, and community organizations whose mission is to improve healthcare access for underserved and vulnerable populations in the city and county. MAPPR is a Practice-Based Research Network founded in 2006 with funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The network’s goal is to use principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR) to bring different sectors of the community together and create positive change by improving healthcare and overall quality of life. The core team consists of researchers from the Carolinas HealthCare System’s Department of Family Medicine and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte (UNCC). Specific UNCC collaborators include the Metropolitan Studies unit, the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, and the College of Health and Human Services. A network of community-based partners includes community clinic within Carolinas HealthCare System; free/low-cost primary care clinics, and community advocacy and social service organizations. Charlotte’s largest and oldest Hispanic service and advocacy organization, the Latin American Coalition (LAC), is a core collaborator that is often the first point of contact for Hispanic immigrants settling in the Charlotte area (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Community Advisory Board Members

In the Fall of 2011, MAPPR designed and facilitated a Photovoice project in collaboration with the LAC’s “United 4 The Dream” (U4TD) program and UNCC’s undergraduate neighborhood planning class. U4TD is a youth-led, 95% Hispanic, high school-aged advocacy group committed to fighting for equal access to higher education, civil liberties, and jobs for immigrant and minority community members in Charlotte.

This Photovoice project is part of a larger ongoing study, A Transdisciplinary Approach for the Evaluation of Social Determinants of Health, which seeks to identify and address social determinants of healthy communities using the CBPR model. The “social determinants of health” framework acknowledges that interacting social, spatial, cultural, environmental, and economic characteristics of individuals and neighborhoods are major contributors to health. The goals of the project are to develop novel and innovative approaches to reduce health disparities and improve access to and utilization of primary care and preventative services, specifically focusing on Hispanic immigrants.

As part of MAPPR’s CBPR approach, the research process actively engages community members in all steps of the research process. The study design incorporates four key steps. (i) Identify quantitative data that describe the major social determinants of health based on qualitative community input. Examples include Census data, health services utilization information, and crime statistics. (ii) Develop geospatial models using the social determinants data to identify neighborhoods at high risk of suffering from health disparities.9,10 (iii) Validate and ground truth these models using qualitative and participatory methods such as Photovoice. (iv) Build neighborhood-level interventions that positively impact health by addressing the specific social determinants identified through the prior steps of the research process. This paper describes an essential and highly impactful part of the work done in the third step of this larger study. Although full details of the study design have been previously published, it is important to outline our research approach.11 We follow a triangulated and inductive approach to building knowledge from empirical work in a recursive and reflexive fashion. Themes or trends are identified from the data at each stage then checked against information previously collected which in turn helps to guide whether and how more data need to be gathered. Consequently, at each stage we are refining our findings and using repeated checks with the data to build understanding that is comprehensive and more thoroughly “grounded” in the real world than it would be were we to have relied on traditional methodologies.12,13

Methods

The MAPPR research team began this project by identifying the primary social, environmental, and spatial determinants of health of the Hispanic community in Charlotte using qualitative data derived from key informant interviews and focus groups with community members and service providers. The five major themes derived from the interviews (immigration/acculturation, education, safety, socioeconomic status, and healthcare utilization) were then compared with findings from an extensive literature review and matched with quantitative data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Charlotte Mecklenburg School data, and Charlotte City data describing crime rates and neighborhood safety. The healthcare utilization components were determined using hospital data showing inappropriate utilization of the emergency department, hospitalizations, and primary care access. Using a previously described approach, geospatial models were developed to pinpoint neighborhoods that were at high risk for health-related disparities.9,10 Photovoice was then used to further validate these models and illuminate the lived experience of the community through the perspective of Hispanic youth. As a participatory technique, the use of Photovoice lends itself well to incorporation within a broader CBPR study and we saw further potential in this approach as part of a community–campus–healthcare system partnership. In particular, the use of Photovoice enabled preexisting partnerships to be expanded to include more community members (as opposed to community advocates or representatives) and to bring voice and insights from youth living in, or actively familiar with, the identified neighborhoods. Our pairing of university planning students with Hispanic high school students to conduct the Photovoice field work further allowed for a reciprocal sharing of knowledge and skill sets. The Community Advisory Board (CAB) chose to approach youth from U4TD for this Photovoice project because of the groups already existing work and advocacy in the community surrounding social justice issues for the Hispanic immigrant community. All of the youth who chose to participate in the Photovoice process either lived in or had strong ties to the neighborhoods where they took photographs and provided the research team and CAB with an insider view of the neighborhoods that are at the heart of our research. For the field work component of the project, the CAB additionally approved the pairing of these U4TD high schoolers with university students enrolled in a UNCC neighborhood planning class also focused on issues of social justice for underserved communities.

Photovoice Methods

The Photovoice method was developed as a public health research tool, and has been used in other youth health promotion projects. The goal is to use photographic images taken by people with little money, power, or status to enhance community needs assessments, empower participants, and induce change.14–17 This methodological approach was selected by the MAPPR research team and approved by the CAB overseeing the larger research project. Photovoice is an integral component of our mixed-methods study because it reveals visual, perceptual, and contextual information about both neighborhoods and the communities within them that is often underrepresented or inadequately understood using more traditional research methods. We took a novel approach by using Photovoice results as another way to validate previously collected qualitative and quantitative data and to add additional insight into the everyday realities of the neighborhoods and communities with which we were working. Carolinas HealthCare System’s Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for both the larger research project and the Photovoice substudy described herein.

This Photovoice project included the following steps: Training and consenting of the participants, picture taking, discussion and picture selection, story development, sharing, and evaluation. Two groups of students participated: 11 (6 male and 5 female) students enrolled in a neighborhood planning course at UNCC and 13 (3 male, 10 female) local Hispanic high school students that were part of the U4TD group. For the UNCC students, participation was part of their coursework. As noted, the selection of the U4TD group was purposeful in that this group already had experience in community activism centered around social justice issues impacting that immigrant Hispanic community. Only those who lived in the specific neighborhoods that were selected via our model or frequented the neighborhood regularly (e.g., had family members or businesses in the area) were selected to participate. All participants spoke English well. Before field work, both the U4TD and UNCC students were asked to attend a training session led by MAPPR research staff. The 5-hour training covered human subjects’ research and etiquette, the MAPPR network design, the overall study goals and methods, the CBPR approach to research, Photovoice methods, and basic photography skills. The training content was developed by research members based on previous Photovoice studies and guides.14–17 The few students who were unable to attend the (full) training session were informed of topics covered in a phone conversation with one of the researchers and sent the materials used during the training.

The university and high school students were placed in small groups and deployed into four targeted neighborhoods, taking on the role of co-investigators rather than research subjects. They were paired in groups with at least two members having attended the full training session. The groups were asked to take pictures of elements in the targeted neighborhoods that in their view impacted health both positively and negatively. To prevent the characterization of the community based solely on pathology, special emphasis was placed on students identifying resources in the community that would assist in overcoming health problems and show the benefits of living within the targeted neighborhood. The teams spent 3 to 5 daytime hours walking and driving through the neighborhoods. As instructed in the training, they took pictures subtlety and were careful not to take pictures of (identifiable) people. They were provided English- and Spanish-language brochures with information about the research group and study to pass out if they were approached and asked about what they were doing. The teams used Vivitar iTwist X014N HD 10.1 megapixel cameras. After the photography excursions, the U4TD students met with a research team member at the LAC to review and select a subset of pictures for further analysis. The students selected the pictures that in their view most accurately represented the social determinants of health encountered in the neighborhood by the Hispanic community. In many cases, multiple pictures were taken of one thing at multiple angles. In that case, their preferred angle and the sharpest image were selected. Students were then asked to prepare a paragraph describing the images in the selected photographs. They were guided by the discussion questions in Table 1, based on the SHOWeD framework which is commonly used in Photovoice to engage participants in critical reflection of their photographs (Table 2).18

Table 1.

Participants

| United 4 The Dream | UNCC Planning Students | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 3 | 6 |

| Female | 10 | 5 |

Table 2.

Reflection Guiding Questions

| Why did you choose this picture? |

| What do you see here? |

| What is really happening here? |

| Who are impacted? |

| How does it relate to our lives or the health of our community? |

| Why does this situation, concern or strength exist? |

| Does it make you think of opportunities for change/intervention? |

These Photovoice findings were reviewed by MAPPR researchers and presented to the project’s CAB. In an effort to empower and offer further training, MAPPR invited the Hispanic youth to take an active role in exhibiting the research findings. The LAC hosted a Photovoice event and the students displayed and discussed their work for LAC staff, their families, researchers, and the CAB. After the event, all U4TD students were recognized in a letter sent to their homes and high school principals, outlining their important research role in a community health project. MAPPR team members encouraged students to use the letter for college and scholarship application packets.

Results

The student teams recorded almost 300 pictures that they narrowed down to 45 images best representing the points they wanted to make about the social determinants of health in their neighborhoods. After the students’ analyses and presentation of their findings, members of the research team analyzed the pictures and descriptions to identify the most frequently featured topics. After discussions of the pictures with the students and the CAB, we then collectively decided on a finalized list of common themes identified through this process as key community health concerns across the different student teams and neighborhoods:

Connectivity, or the Lack Thereof (Sidewalks), and Dangerous Crossings

Numerous pictures showed people trying to cross roads without proper crossings or roads without sidewalks, which were portrayed pedestrian unfriendly. This was expressed as a particular concern for individuals without access to personal motor vehicles.

Trash and Lack of Property Maintenance

Many pictures are taken of scattered trash on the streets and of the poor housing conditions in the area, especially in some of the apartment complexes. These were viewed as visible signs of deterioration that compromised the well-being of the inhabitants.

Visible Water and Air Pollution

Trash and unclean standing waters surrounding the apartment complexes are shown in the pictures. There is also a picture of a power plant next to a Boys & Girls Club. Such images were viewed as representative of potential health hazards for neighborhood residents.

Physical Evidence of Gangs, Criminal Activity, and Vagrancy

Graffiti, public drinking, and a homeless man sleeping in a playground are featured in the students’ pictures and mentioned as undesirable features that invoke feelings of unsafe spaces. Safety and the presence of unsafe areas within the neighborhood were presented as a threat to women and children. Fear of kidnapping, rape, or a car hitting a pedestrian were prevalent stories describing negative factors that influence health. Places where these events may have happened were photographed by the youth and they wrote about them in their paragraphs. Additionally, the documentation of trash and empty and/or broken beer bottles was used to describe the impact of alcohol abuse on the community. Specifically the participants described men gathering and drinking together in various places that children access, including playgrounds and athletic courts.

Positive and Negative Features

Women Infant and Children offices, grocery stores, a new fire station, and schools were identified by Photovoice researchers as positive resources in the community, whereas fast food restaurants and a potential “scam doctor” are identified as negative. Particular neighborhood spaces were also presented as both positive and negative, depending on their use and upkeep (e.g., track, athletics courts, playgrounds can be used for physical activity and leisure but also for criminal activities like public drinking and sexual assault).

After the presentation and review of the Photovoice research findings, the MAPPR researchers were challenged to reconsider earlier assumptions. The Photovoice work triggered a set of new discussions within the research team regarding group differences within the Hispanic community and how spaces within the urban landscape can act as both positive and negative features. The photos and discussions with the youth made us aware that the social constructs and activity patterns for single immigrant men and families are very different and needed to be taken into more explicit account in both research analyses and intervention development. For instance, the activities in which the single men or gangs were depicted as involved—like public drinking—were presented as being in conflict with the activities in which children were engaged—like playing outside. Because of the lack of communal space in the neighborhoods, behaviors and substances that may jeopardize the safety or feelings of security for women and children are taking place in spaces designed for child play (playground) or exercise (track). Community resources that are generally considered to be assets, like playgrounds, can also be judged as unsafe and unhealthy by community members when they are poorly maintained and occupied by gangs or vagrants. Health interventions need to recognize these critical differences in behaviors and needs. This finding led researchers to consider how part of a health intervention may include forming groups that would walk together or play soccer together to “take back” the spaces that are currently used for activities viewed by the community as inappropriate or unhealthy.

A similarly assessed community resource was the road infrastructure. The Photovoice research showed that although arterial roads running through these neighborhoods provide access to bus transportation and easy access to many other parts of the city, they are also considered safety hazards because of limited crosswalks and lights, as well as the numerous accidents that have occurred where pedestrians have been injured or killed. In this case, the research team and CAB was made aware that intervention development and location needed to take into account not only accessibility, but also the safe travel of participants.

The results of the Photovoice study also helped the researchers and CAB to confirm the validity of the factors included in the earlier developed geospatial models identifying neighborhoods at high risk of suffering from health disparities. The photos, written narratives, and presentations of the students included unprompted mention and discussion of several of the variables included in the models. As such, the Photovoice work of the students added a layer of confirming, qualitative findings onto to the scholarly literature review and interviews previously conducted with community members and providers in the area (Table 3). Variations in healthcare utilization and the prominence of social variables directing the Geographic Information Systems model (immigration/acculturation, education, safety, and socioeconomic status) were all identified as significant issues within the identified neighborhoods through Photovoice.

Table 3.

Common Themes

| Connectivity, or the lack thereof (sidewalks), and dangerous crossings |

| Trash and lack of property maintenance |

| Visible water and air pollution |

| Physical evidence of gangs, criminal activity and vagrancy |

| Positive and negative features |

| Positive: Women Infant and Children offices, grocery store, a new fire station, schools |

| Negative: fast food restaurants, potential scam doctor |

| Spaces were also presented as both positive and negative, depending on their use and upkeep (e.g. track, athletics courts, playgrounds) |

In addition to variable confirmation, Photovoice results provided information that the geospatial models could not address or illuminate. For example, several large apartment complexes were identified during the Photovoice study as being home to many of the newest immigrants living in the community. These complexes form distinct micro-neighborhoods that provide needed housing and communities of kind to the most vulnerable, recently arrived immigrant populations. These areas were not previously identified during the quantitative development of the geospatial models, but rather through discussions with Hispanic students, the research team were able to identify these and learn more about the ways that they could benefit from improved access to healthcare services. The invisibility of these areas in the study up to this point reinforced the notion that, although the community-level data gleaned through census-based, government- and hospital-derived sources are extensive and reliable, they can become quickly outdated or underestimate certain populations. This is especially true for disenfranchised or at-risk populations. Therefore, field-based assessments and qualitative analyses are especially crucial for understanding rapidly growing immigrant populations and transitioning communities.

Discussion

Racial and ethnic minorities and immigrants often suffer from health disparities that are based on underlying social determinants of health. Research studies examining inequalities and social determinants at a neighborhood scale are limited; to be effective, these studies must engage community members at all levels. This project worked with youth activists and enabled them to become research collaborators working to identify the social determinants of health that are visually expressed in their communities, neighborhoods, and daily lives. The CBPR framework and existing partnership between MAPPR and the LAC were essential to this project’s success, allowing for the development of equitable partnerships between clinicians, health researchers, and the Hispanic community to take place.

In this study, MAPPR built on existing research capacity and created new relationships with high school-aged community members that proved crucial to success during the next steps of intervention development. The Photovoice project was utilized to validate and supplement data and findings developed in earlier phases of a larger research investigation. It was also used to deepen and develop a more nuanced understanding of the communities, neighborhoods, and individuals at the heart of our research and intervention efforts. For instance, the research team had previously been informed by community members and provider of the critical role that the apartments play in the immigration process. This was confirmed by the youth, whose pictures and comments often revolved around life and social dynamics in apartment complexes. This led the team to create new connections with the complexes and to target them for community participant recruitment and as possible intervention sites. Additionally, through the Photovoice analysis, we were able to identify particular complexes in which micro-communities of particularly vulnerable populations were resident and potentially in need of more targeted and tailored assistance.

The Photovoice initiative has thus improved the precision of MAPPR’s understanding about the diversity within the neighborhoods and communities in which we work in terms of demographics, physical feature impacts, and nuanced insights into resource assessment and utilization. We realize that, although our four targeted neighborhoods have similar large-scale characteristics, there are significant differences. These place-specific factors need to be weighed when devising intervention programs. Consequently, the MAPPR research team reevaluated our approach to neighborhood resources and issues and added additional key informant interviews and resident focus groups to gain a better understanding of the complexity of community health issues. Although these additional tasks were not a part of the original research timeline, they enhanced our understanding of critical issues and provided an additional layer of community participation.

Beyond the research insights from the Photovoice process, we gained valuable practical experience working with young people. Given the diverse backgrounds and circumstances of high school-aged students, communication and organization were essential. It was challenging to have students attend all meetings, in part because of their schedules, limited transportation options, and other time commitments. Because of this, not all students were able to attend the on-site training; we resolved this by ensuring that those who were absent received phone calls and information packages in the mail. Sending out reminders via text proved to be much more effective than using email for both university and high school students.

Moreover, it could be considered a limitation to only have youth participate in the project because they likely have different perspectives on determinants of health than adults. That said, this group of youth often take on many “adult” responsibilities in their families (as is common in Hispanic immigrant communities) and are active leaders in their community, making them well aware of issues relating to access to services and personal and community health. Allowing older adults to participate in a similar project could be an opportunity to enhance the information in future studies.

Future CBPR with minors and non–English-speaking parents should take into account that the consent process can be lengthy. In our case, the English consent forms had to be officially translated in Spanish, and submitted to CMC’s IRB. A copy of the consent in both languages was sent to the high school students’ home address for the student and parent/caretaker to sign. The students were reminded to bring their signed consent form to the training session. Students who were unable to attend training had to bring their form when we met for the picture-taking trip to participate and receive a camera.

The Photovoice experience was a learning opportunity for the MAPPR team, the UNCC students, and the U4TD students, but in different ways. During the training, discussions with the high school students about the Latino community in Charlotte and some of the challenges they face were a humbling and transformative experience for MAPPR members and UNCC students. At the same time, the U4TD students gained information and skill building with respect to research conduct. The reflective process of documenting and describing their neighborhood also helped them to see their community in a different light. Perhaps most important, they expressed feeling recognized and empowered because their opinions were taken into consideration and they were acknowledged as equal research members, and even experts. At the public meeting hosted by the LAC, the youth expressed a sense of accomplishment and gratitude for the opportunity to broaden their activism around the promotion of immigrant rights and health services access.

This Photovoice project also provides new insights into the CBPR process. It presents ways to collaborate effectively with university and high school students to identify potential social determinants of health and demonstrates the use of Photovoice as part of a larger methodology in a participatory research study. Specifically, we applied Photovoice to conduct a form of landscape analysis that shed light onto the lived experiences and perceptions of neighborhood contexts that in turn allowed us to better understand the complex dynamics of community health determinants. It also facilitated the triangulation of Photovoice findings with data collected through other means and at earlier phases of the study and the experiential knowledge of different community groups with the practical and scholarly knowledge of the research team and CAB. We therefore believe that this paper may be useful to other partnerships who wish to incorporate Photovoice in mixed-methods participatory research as a way to more fully understand neighborhoods and lived experiences through the eyes of community members. We continue our involvement with the students and their families, for example by inviting them to participate in a subsequent Neighborhood Forum and upcoming community wellness events. MAPPR also hired one of the older U4TD students to assist with the intervention phase of the NIH study and help to conduct public meetings. In summary, Photovoice led to more effective community outreach, improved trust between the research team, Charlotte’s Hispanic communities, and the organizations and providers in Mecklenburg working around issues of immigration and community health and to enhanced community capacity.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (R01 MD006127).

The authors are grateful for the Latin American Coalition and the university and high school students for their participation and valuable contributions.

Appendix A

The quotes are taken directly from the paragraphs the students wrote about their selected pictures.

Figure A1. “Public transportation helps those of us who may not drive get around, whether it is to a doctor’s appointment or to school. One of the biggest issues with transportation is the placement of the bus stops. In this picture, you can see a family with a baby in a stroller crossing Eastway Drive, which is a busy intersection with a set speed limit of 45 MPH. This is a threat to health because people can get hit by a car, and end with serious or life-threatening injuries.”

Figure A2. “In the photo above, you can see some children playing with cardboard boxes in the “ABC” apartments. You may be wondering how that is a health concern, and the answer is simple: the children got the boxes from the dumpster. Interacting around the dumpster can lead to the spread of infectious diseases and other potentially hazardous substances.”

Figure A3. “The Boys and Girls club of Charlotte poses as a sanctuary for many children in this urban area. The most ironic thing however is that it’s located beside a huge electrical power-plant. The power-plant is beneficial to the area but harmful to be so close to children. It relates to the health of our community because the club cannot fulfill its intent with dangerous restrictions such as the power plant. This problem can be fixed by isolating it further from people and children.”

Figure A4. “We found trash, empty beer cans, and a homeless man in the park. This means the children cannot use it to play.”

Figure A5. “Doctors For What? Another issue that many communities seem to face is fraud medical help, because sadly, in this world there are people who would rather take advantage of the lower income families and communities. … This example of Latino exploitation is a serious risk to the community because not only does the Latino community not get the proper health care, they will also have a lack of trust in any health care place.”

Figure A6. “The construction of a local fire department is a positive for the community in this track because it provides an extra service for communities there. They will have a better chance of being safer and more protected from fires because of the proximity of the fire department.”

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau 1980–2010.

- 2.Arredondo EM, Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell NR. Is church attendance associated with Latinas’ health practices and self-reported health? Am J Health Behav. 2005;29(6):502–11. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer HM, Rodriguez MA, Quiroga SS, Flores-Ortiz YG. Barriers to health care for abused Latina and Asian immigrant women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2000;11(1):33–44. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berk ML, Schur CL, Chavez LR, Frankel M. Health care use among undocumented Latino immigrants. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19(4):51–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duke MR, Bourdeau B, Hovey JD. Day laborers and occupational stress: Testing the Migrant Stress Inventory with a Latino day laborer population. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2010;16(2):116–22. doi: 10.1037/a0018665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Parra-Medina D, Talavera GA. Health communication in the Latino community: issues and approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:227–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenlees CS, Saenz R. Determinants of employment of recently arrived Mexican immigrant wives. Int Migr Rev. 1999;33(2):354–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ransford HE, Carrillo FR, Rivera Y. Health care-seeking among Latino immigrants: Blocked access, use of traditional medicine, and the role of religion. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):862–78. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dulin MF, Ludden TM, Tapp H, Blackwell J, Urquieta de Hernandez B, Smith HA, et al. Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to understand a community’s primary care needs. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(1):13–21. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.01.090135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dulin MF, Ludden TM, Tapp H, Smith HA, Urquieta de Hernandez B, Blackwell J, et al. Geographic information systems (GIS) demonstrating primary care needs for a transitioning Hispanic community. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(1):109–20. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.01.090136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cope M. Coding qualitative data. In: Hay I, editor. Qualitative research methods in human geography. 3. Ontario, OUP Canada: Don Mills; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dulin MF, Tapp H, Smith HA, Urquieta de Hernandez B, Coffman MJ, Ludden T, et al. A trans-disciplinary approach to the evaluation of social determinants of health in a Hispanic population. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:769. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Cash JL, Powers LS. Who knows the streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action through Photovoice. Health Promot Pract. 2000;1(1):81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C, Morrel-Samuels S, Hutchison PM, Bell L, Pestronk RM. Flint Photovoice: community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):911–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Necheles JW, Chung EQ, Hawes-Dawson J, Ryan GW, Williams LB, Holmes HN, et al. The Teen Photovoice Project: A pilot study to promote health through advocacy. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(3):221–9. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Behav. 1988;15(4):379–94. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]