Abstract

Conventional DNA replication is initiated from specific origins and requires the synthesis of RNA primers for both the leading and lagging strands. In contrast, the replication of yeast mitochondrial DNA is origin-independent. The replication of the leading strand is likely primed by recombinational structures and proceeded by a rolling circle mechanism. The coexistent linear and circular DNA conformers facilitates the recombination-based initiation. The replication of the lagging strand is poorly understood. Re-evaluation of published data suggests that the rolling circle may also provide structures for the synthesis of the lagging-strand by mechanisms such as template switching. Thus, the coupling of recombination with rolling circle replication and possibly, template switching, may have been selected as an economic replication mode to accommodate the reductive evolution of mitochondria. Such a replication mode spares the need for conventional replicative components, including those required for origin recognition/remodelling, RNA primer synthesis and lagging-strand processing.

Keywords: mitochondrial DNA, yeast, replication, recombination, rolling circle, template switching

Insight into the mechanism of mitochondrial DNA replication in both higher and lower eukaryotes has not been straightforward. With metazoans that have a defined small circular genome, there has been a controversy between proponents of a strand-displacement model1 and advocates of a strand-coupled mode of mtDNA replication2, 3. Evidence supporting the strand-displacement model has been presented that demonstrates participation of the light strand origin of replication, OriL4, 5. In the strand-coupled mechanism OriL is not required. In this article we focus on mtDNA replication in yeasts where mtDNA differs from metazoans both in size, configuration and number of encoded genes. We first summarize structural features of yeast mtDNA relevant to replication. We emphasize on the data accumulated in the last 4 decades that refutes an absolute requirement of an origin for mtDNA replication. Reanalysis of previously published data together with more recent findings in the field leads to the proposal that yeast mtDNA may be replicated by coupling recombination, rolling circle replication and template switching, which allows the synthesis of both leading and lagging strands independent of specific origins and various replicative components that are used in conventional DNA replication.

A role for rep/ori for mitochondrial DNA replication in yeast?

mtDNA in yeasts can vary both in size and form, that is, circularity or linearity. As early mapping studies showed, there is no correlation between size and number of encoded genes6. In sequenced mtDNAs of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (19 kb)7, Candida glabrata (20 kb)8 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (85 kb)9, there is nearly the same type and number of genes. An exception to this is found in some yeast genomes that encode seven genes of the NADH dehydrogenase complex10. However, for the three mtDNAs mentioned above, differences in mtDNA are due to the number and size of introns and the amount of non-coding sequence between genes. Intergenic regions in yeast mtDNAs can consist of AT rich segments and smaller GC rich palindromic clusters11–13. In addition, S. cerevisiae mtDNA contains three or four copies of a GC rich sequence element termed rep or ori that was thought to contain an origin of replication.

In the conventional view of DNA replication it is expected that there is a special sequence, an origin, where synthesis of DNA can start. At this region a short RNA segment has to be made by a primase enzyme followed by DNA synthesis with a DNA polymerase. Because rep/ori regions of S. cerevisiae mtDNA contain a consensus transcriptional promoter it seemed reasonable that they could be origins of replication. The discovery of rep/ori elements arose from observations with petite colony mutants of bakers yeast14. Petite mutants cannot grow on non-fermentable carbon sources as they are deficient in enzymes of respiration. Respiratory deficiency can result from mutations in mtDNA (cytoplasmic changes), or from alterations of nuclear genes. In the former class, mutations can result from loss of more than 99% of mtDNA sequence. Some of these deleted mtDNAs in haploid strains, when crossed to respiratory competent strains, can result in more than 95% of diploid progeny being respiratory deficient15. These mutants were termed highly suppressive (HS) and were subsequently shown to have a 280–300 bp segment of mtDNA with 3 conserved GC rich sequences11, 12. This sequence organization shares some similarities to the heavy strand origin of mtDNA replication in mouse and humans16. Furthermore, a consensus nonanucleotide promoter for mitochondrial RNA polymerase, Rpo41, was identified in HS rep/ori sequences that is disrupted in inactive elements17, 18. Subsequent studies showed that RNA was indeed transcribed from intact promoters leading to DNA synthesis17–20.

However, it became unlikely that intact rep/ori elements were the sole arbiters of mtDNA synthesis by the observation of surrogate origins of replication in petites lacking rep/ori segments21. Ultimately it was found that moderately suppressive petites, with only 70 or 89 bp of repetitive AT sequence, lacked GC bp22. In other words, if an origin of replication exists it need not have GC bp. In further work Fangman and colleagues found that Rpo41, the only mtRNA polymerase, is not required for replication of mtDNA of petite genomes23, 24. As noted by the authors, their results imply that there is another way to start mtDNA replication that does not require RNA transcripts as primers. An outstanding conundrum raised by these studies is the observation that Rpo41 is required for maintenance (replication) of an entire (wild type) genome as well as for transcription25. As mitochondrial protein translation is required for the maintenance of wild type but not petite genomes26, via a yet unknown mechanism, the question remains unresolved as to whether the maintenance of the wild type mtDNA is actually dependent on transcription or simply, the translation products of Rpo41-derived mRNAs.

Further studies have indicated that rep/ori elements are not universal in mtDNA of yeasts. No rep/ori elements were found in the intergenic regions of the mitochondrial genome in C. glabrata27 and in the first completely sequenced mtDNA of Hansenula wingei28. It now appears from complete sequences of yeast genomes, including mtDNAs, that only S. cerevisiae and close relatives have rep/ori elements. Consequently, it is not unreasonable to believe that this segment of DNA has been gained by horizontal gene transfer of a heavy strand origin of replication from an early metazoan to an ancestor of S. cerevisiae after close relatives such as C. glabrata, Saccharomyces castellii and Saccharomyces servazzi had already diverged29. In summary, it now appears that most yeast species have no recognisable origin of mtDNA replication that generates RNA primers made with the RNA polymerase Rpo41.

mtDNA conformation

In a comprehensive review tracing work on mtDNA structure in yeasts, Williamson outlined initial evidence supporting the circularity of the genome and how this view was overturned30. Circularity was inferred by analogy to the form of metazoan mtDNA and corroborated by the restriction site map of the baker’s yeast mitochondrial genome. Support was also obtained by an electron microscope picture of a yeast mtDNA supercoiled molecule31 and a relaxed circular molecule was seen in another study32. Long linear molecules were explained as ‘broken circles’ because of the large 85 kb size of the genome. However, it became straightforward to isolate adequate amounts of supercoiled circular DNA from yeasts with smaller, 20–40 kb, genomes33, 34. The basis of the isolation technique was ethidium bromide (EtBr)/CsCl buoyant density centrifugation following Braun shaker homogenization of yeast cells with the extraction buffer containing EtBr to minimize endonuclease activity. By this method supercoiled circular molecules as large as 57 kb from Brettanomyces anomalus were obtained35. Sizes of circular mtDNA molecules from yeasts as well as other fungi and Oomycetes up to 1991 have been listed in a review6. At this time only 2 linear yeast mitochondrial genomes had been reported, but things were about to change in two respects. Firstly, several yeasts were shown to have linear mtDNA and secondly, circular mapping genomes were found to exist mainly as linear polydisperse molecules.

By using pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and electron microscopy Maleszka et al. demonstrated that the small 19–20 kb mtDNA genome of Candida (Torulopsis) glabrata had 3% supercoiled circular molecules, 6% relaxed circles, 53% linear and 37% of the molecules remained at the top of the gel36. Linear molecules varied in size from 50–150 kb. Clearly, these molecules were not derived from broken circles of the 19 kb genome. More telling was when DNA of the 9.5 kb circular plasmid, pMK2, was introduced into either the nucleus or mitochondrion of S. cerevisiae. It was discovered that it replicates as a 2 micron plasmid in the nucleus or in a conformation having linear polydisperse molecules varying from 23–100 kb in the mitochondrion. This surprising result emphasized that the majority of mtDNAs in mitochondria of yeasts consists of polydisperse linear forms even though, in the case of pMK2, it starts in a circular configuration. Support for the view that the majority of mtDNAs in some lower eukaryotes are polydisperse circular-mapping linear molecules has been assembled in a comprehensive review covering genomes from fungi and plants37.

Although the majority of yeast mtDNAs are circular mapping, two species, Hansenula mrakii (now Williopsis mrakii)38 and Candida rhagii (now Candida parapsilosis)39 were the first yeasts reported to have linear genomes. By 1995 several yeasts were shown to have linear mtDNA with specific termini40–42. Of particular interest was the observation that species with linear genomes had close relatives with circular forms42. Indeed, a small number of double-stranded monomer circles were seen in an electron microscope study of Pichia piperi having linear mtDNA41. Based on the above data it was suggested that interconversion between linear and circular mtDNAs of yeasts may have occurred by relatively simple mechanisms43. It was proposed that mitochondrial telomeres could be derived from mobile elements that invaded mitochondria and integrated into circular mapping polydisperse linear genomes, a not unreasonable supposition in view of the restricted distribution of rep/ori sequences described previously. Recombination through integrated mobile or resolution elements a genome length apart, would form linear molecules of unit length with the resolution segments forming telomeres. Further studies have led to the identification of a putative telomere–binding protein in C. parapsilosis44 and a protein covalently attached to the 5’ termini of linear mtDNA of C. subhashii45. Additionally, a suggestion has been made that linear molecules with defined ends may provide an advantage to cellular proliferation over circular polydisperse genomes46.

In sequencing studies of mtDNAs from 8 yeasts related to C. parapsilosis it was found that genome structures encompassed linear and circular mapping and multipartite forms. It was hypothesized that inverted repeats play a crucial role in allowing resolution of a circular mapping genome into a linear form. Furthermore, a suggestion was made that linear-mapping genomes with terminal structures such as t-hairpins are a transient state between circular mapping and true monomeric linear genomes47.

Replication of yeast mtDNA - why a mystery?

Any attempt to gain insight into mtDNA replication by analogy to conventional coupled leading and lagging strand synthesis confronts the fact that some of the enzymes for this process are not present in mitochondria. For instance, the yeast genome does not have genes for a mitochondrial primase, ribonuclease H or a topoisomerase. Nor is a mitochondrial targeting signal sequence a common component of nuclear-encoded proteins for these enzymes eliminating a dual location, although DNA-transacting enzymes have been reported to target both the mitochondrial and nuclear compartments (e.g., the Pif1 helicase48). Furthermore, mtDNA polymerase consists of a single sequence with no attendant subunit encoding a processivity factor49. The apparent non-existence of the above proteins, and the dispensability of RNA priming and origin of replication, are consistent with the possibility that mtDNA replication in yeast occurs by an unconventional mechanism as outlined below.

Evidence for rolling circle replication

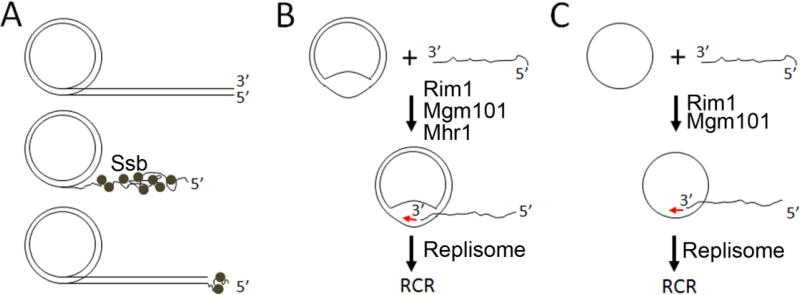

The mild technique of PFGE has shown that the conformation of mtDNA in Candida (Torulopsis) glabrata, S.cerevisiae36 and S. pombe50 is mainly linear of 50–150 kb with approximately 10% being super coiled and relaxed circles. With C. glabrata, using harsher preparation conditions for electron microscopy, it was found that in addition to linear forms, there were supercoiled and relaxed circular molecules, circles with single or double stranded tails (lariats, Figure 1A) and Y and H forms. Some double stranded tails were longer than a genome length suggesting they could have been produced by rolling circle replication (RCR). Similar DNA structures including circles with collapsed single stranded tails have been observed in mtDNA of the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum51. Like the yeasts mentioned above it has been proposed that replication of mtDNA in P. falciparum takes place by a rolling circle mechanism. RCR could be initiated by nicking of one DNA strand in a circular molecule followed by addition of residues to the free 3’ end by DNA polymerase. Whether a specific nicking activity is present in mitochondria to control DNA replication is unsettled. Alternatively, it has been suggested that recombination, characterized by the invasion of a pre-existing circle by a linear molecule with a free 3’ end, could prime the synthesis of the leading strand (Figure 1B). Neither nicking of double stranded mtDNA nor recombination in the S. cerevisiae mitochondrial genome requires to occur at specific sites, consistent with the observation that there is no special sequence for replication initiation in different petite mutants that may retain less than 1% of the mitochondrial genome22, 52. RCR was observed on either DNA strand as found in S. pombe50, similar to what was observed during late replication of phage lambda53.

Figure 1.

Rolling circle replication (RCR) of mtDNA in yeast. (A) Schematics for potential intermediates resulting from rolling circle replication of C. glabrata mtDNA, as revealed by electron microscopy36. Upper panel, mtDNA circle with double-stranded lariat; middle panel, mtDNA circle with a collapsed lariat which likely represents ssDNA bound by single strand binding protein; bottom panel, mtDNA circle with a collapsed lariat end, likely representing incompletely replicated lagging strand. (B) Model for the invasion of a processed double-stranded mtDNA circle by single-stranded linear DNA, which primes rolling circle replication. (C) Mgm101 catalyses the annealing of single-stranded linear DNA with a singled-stranded circle to initiate RCR.

Mechanism of replication initiation

The core mtDNA replisome consists of a DNA helicase to unwind the double stranded DNA template, a polymerase (Polγ) to synthesize the nascent strands, and a single strand DNA binding (Ssb) protein that stabilises the displaced single stranded DNA. The Polγ and mitochondrial Ssb proteins are evolutionarily related to those in bacteriophages54, suggesting a potential commonality in DNA replication between mtDNA and the phage genomes. If yeast mtDNA replication proceeds in a RCR mode, a central question is how the process is initiated. A gene encoding a topoisomerase I activity that can potentially nick the double stranded circles has not been identified so far in yeast mitochondria. Several studies have suggested that recombination may play a role in mtDNA replication23, 51, 55. More recent studies have shown that mtDNA replication forks in C. albicans and C. parapsilosis are unequivocally mapped near the recombination sites56, 57. Furthermore, yeast mitochondria possess a single strand annealing protein (SSAP) of bacteriophage origin, defined by the Mgm101 protein. This led to the proposition that homologous recombination, via single strand annealing, may play a role in initiating RCR-based replication.

MGM101 was initially discovered in a forward genetic screen for temperature-sensitive nuclear mutants that are unable to maintain the mitochondrial genome58. At the non-permissive temperature, mtDNA copy number in the mutant cells is reduced by two-fold every cell generation, suggesting that Mgm101 may participate in a process critical for mtDNA metabolism59. Early circumstantial evidence suggested that Mgm101 may participate in mtDNA recombination. Disruption of MGM101 was found to cause the loss of the wild-type and the AT-rich non-suppressive ρ− genomes, but not the HS ρ− mtDNAs that contain an active rep/ori sequence59. Mgm101 is therefore dispensable for the maintenance of the ρ− genomes with highly repeated rep/ori sequences. In cells disrupted for both MGM101 and RPO41, encoding the mitochondrial RNA polymerase, the HS ρ− mtDNAs are stably maintained, suggesting the existence of an element that enables the initiation of replication dependent neither on Mgm101 nor on Rpo41-based transcription. As GC-rich clusters in the rep/ori elements of S. cerevisiae mtDNA are regions of intra molecular recombination60, 61, it is possible that the presence of a high density of GC-rich clusters may bypass the requirement for Mgm101 in promoting catalysed or uncatalyzed recombination that primes mtDNA replication. ρ− mtDNAs that lack these recombinogenic elements are therefore dependent on Mgm101 for initiating recombination and replication. The ρ+ mtDNAs have only 3–4 dispersed rep/ori elements, which may not be sufficient to sustain the recombination-based replication of the entire genome.

It was not until recently that Mgm101 was found to belong to the Rad52 protein family. Mgm101 shares only 17% sequence identity with the N-terminal single-strand annealing (SSA) domain of the yeast Rad5262. Like Rad52, Mgm101 has high affinity for ssDNA. It catalyses the annealing of ssDNA coated by the single strand binding protein, Rim1. Structurally, Mgm101 forms oligomeric rings of ~14-fold symmetry63, 64. Single strand annealing and the formation of large rings are salient features of Rad52-family proteins. The latter proteins include Redβ and Erf from the bacterial phage λ and P22, RecT from the prophage rac, and Sak from the lactococcal phage ul36. These proteins, also known as single-strand annealing proteins (SSAP), have barely recognisable sequence identity to Mgm101 despite that they share similar quaternary structures.

Rad52 is involved in homologous recombination. In a canonical recombination pathway, the key player is the Rad51/RecA-type recombinase, which is recruited by Rad52 to ssDNA to form nucleoprotein filaments capable of initiating homology search along a template DNA molecule. Successful homology search is followed by strand invasion and other processes such as DNA synthesis and Holliday junction formation. However, the Rad52-family proteins or SSAPs in bacteriophages lack a RecA interacting domain. These proteins catalyse recombination by the single–strand annealing mechanism independent of RecA. In this alternative recombination pathway, SSAPs are loaded on the ssDNA tails. By an as yet unknown mechanism, the annealing to homologous ssDNA is facilitated.

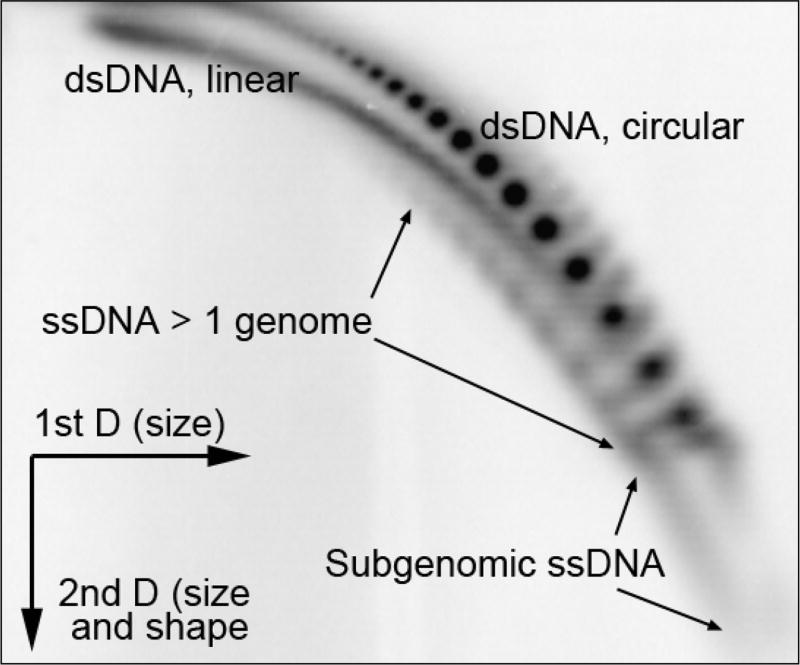

In the context of RCR, the simplest model would be that Mgm101 anneals a single-stranded or 5’-resected double-stranded linear DNA molecule with a pre-existing single-stranded circular DNA (Figure 1B). This generates a free 3’ end that is used to initiate mtDNA replication, independent of primase, RNA polymerase and topoisomerase I. Mgm101 interacts with the mtDNA polymerase Mip165. It is possible that Mgm101 directly recruits Mip1 to initiate replication, immediately following the strand annealing event. As shown in Figure 2, a typical ρ− genome of S. cerevisiae lacking an ori/rep element genome is present in various molecular configurations, including multimeric circles, and double- and single-stranded concatemers. The coexistence of linear and circular DNA species would facilitate the formation of structures for RCR. Regions of ssDNA in a double stranded circular genome may be generated by nucleases, helicases or by the process of DNA replication. The palindromic structures in the ori/rep elements with exposed ssDNA regions may provide natural recombination substrates without enzymatic processing, which at least partially explains the replicative advantage and hypersuppressiveness. Additionally, single-stranded circles displaced by RCR may also be used as a SSA substrate to initiate replication (Figure 1C). In addition to Mgm101, Ling and Shibata proposed that the Mhr1 protein plays a role in initiating rolling circle replication by promoting the invasion of a single stranded DNA into a double stranded DNA circle like Rad51/RecA, which has been comprehensively reviewed66, 67.

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis of the DS400/N1 (430 bp) ρ− genome, showing the coexistence of various mtDNA conformers.

Although recombination-initiated RCR has been discussed in the context of yeast mtDNA, it is an open question whether this replication mode is extended beyond fungi. Recent studies have shown that RCR is the predominant mode of mtDNA replication in C. elegans, despite that mtDNA remains mainly circular in this metazoan species68. On the other hand, electron microscopy revealed that human heart and brain mtDNA has a complex organization with abundant dimeric and oligomeric molecules, branched structures, linear fragments, and prominent four- and three way junctions. Such a conformational ununiformity, although not exactly resembling what is seen in yeast, suggests that homologous recombination may take place with potential implications for replication69.

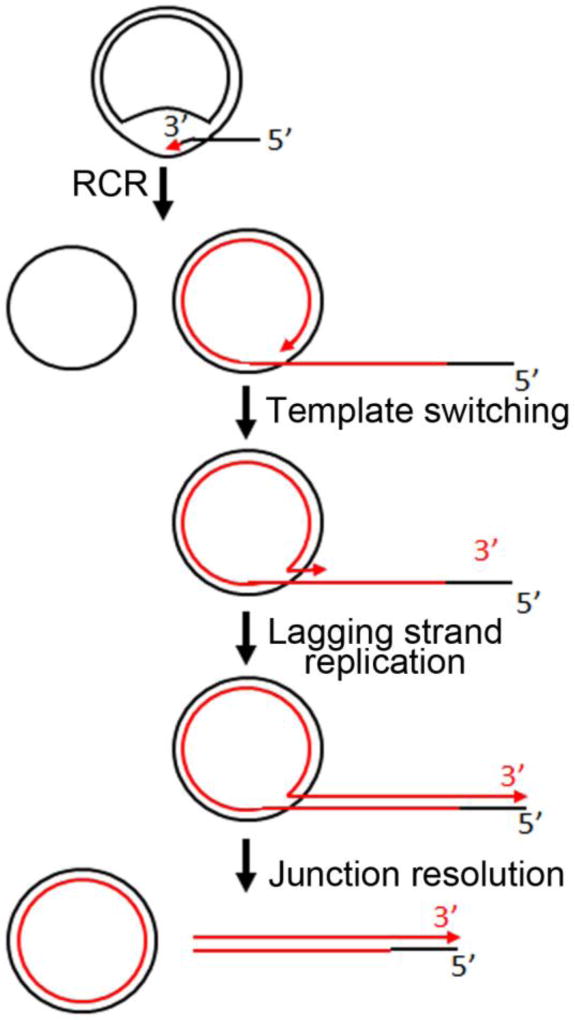

Template switching as a possible mechanism of lagging strand replication

An unsolved problem posed by RCR is how the second strand is synthesised. In the electron microscope study of RCR in C. glabrata two thirds of circles with tails were double stranded while one third had collapsed structures diagnostic of single stranded DNA (Figure 1A)36. The presence of single stranded tails suggests that formation of double stranded forms does not immediately follow the replication initiation event. One possible explanation for this observation is that synthesis of the second strand occurs by a mechanism known as template switching (Figure 3). Previously, second strand synthesis was thought to take place by conventional lagging strand formation involving the production of RNA primed DNA fragments. There is no evidence for this assumption at least in S. cerevisiae, as this process cannot occur because RNA polymerase is not essential for mtDNA replication nor is there a gene for mitochondrial RNase H that would be needed for RNA primer removal.

Figure 3.

Model for lagging strand synthesis, initiated by template switching of the replisome.

Details of double strand DNA formation by template switching have recently been described in RCR of bacteriophage phi 29 from Bacillus subtilis70. In this model, a double stranded tail is made by the DNA polymerase switching from the circular template to the displaced single strand. Once the polymerase has duplicated the single stranded tail, replication stops. One consequence of template switching is that it can account for the presence of circles with subgenomic double stranded tails of variable length as seen in C. glabrata mtDNA36. Lariats with collapsed single-stranded regions at the free end of the tail were also observed (Figure 1A). These molecules may represent uncompleted replicative products following template switching. Upon the completion of the tail, the resolution of tail-circle junctions through enzymatic processing generates double stranded circles and polydispersed linear genomes of varying sizes.

In the phi 29 study it was described that template switching could be stopped by SSB preventing transfer of the polymerase to the displaced strand. In both C. glabrata and P. falciparum51 the presence of circles with single stranded tails is apparent from the collapsed or bunched molecules. The granular appearance of these regions suggests that they may have some attached SSB protein.

Another question raised by RCR in yeasts (and other eukaryotes) is a reason for the persistence of this process in view of the majority of mtDNA being linear as shown in pulsed field gel electrophoresis. This question has also been raised by Williamson and colleagues51. Their view is that RCR is a way of retaining all genetic information in the presence of prolific recombination of mtDNA that could delete vital regions of the genome. Only in petite positive yeasts like S. cerevisiae do such mtDNA deletion mutants survive14.

Concluding remark

Published data does not support an absolute requirement of origins and several molecular components for the synthesis of yeast mtDNA, which are otherwise essential in a conventional DNA replication mode. Recombination-based initiation followed by RCR is likely sufficient to initiate and complete the replication of the leading strand. Retrospective analysis of experimental data supports template switching as a possible mechanism for the synthesis of the lagging strand, which spares the need for additional replicative components including primase, RNase H and even a replicative DNA ligase. Although the rep/ori elements may still contribute to the replication of ρ+ mtDNAs via the RNA-primed mechanism, the predominant role of the recombination-mediated replication mechanism is highlighted by recent observation that blocking of free double strand DNA ends by the bacterial Ku protein destabilizes the mitochondrial genome in yeast71. Recombination-primed replication, RCR and template switching have been well established in bacteriophages. When origin–based replication is programmed to cease, these mechanisms become essential for phage growth. The yeast Mgm101 is evolutionarily related to the phage SSAPs. By analogy, it is not unreasonable to predict that Mgm101 may play a key role in promoting recombination-based replication. The maintenance of both linear and circular forms of mtDNA in yeast may be necessary to provide substrates for this minimalized mode of DNA replication. Many questions remain to be answered in the coming years. For example, it is critical to understand how the replication of the leading strand is licensed and the replisome is assembled in function to cell physiology. There is still much to learn regarding the mechanisms that promote the replication of the lagging strand, including template switching.

Highlights.

Despite several decades of investigation, many questions regarding the replication of mitochondrial DNA in yeast remain unsolved.

This review summarizes the structural features of yeast mtDNA and the molecular machineries for DNA recombination, which support the coupling of recombination with the rolling circle replication mechanism.

Re-evaluation of early published data led to the proposal of template switching as a possible mechanism for the replication of the lagging strand.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of health (NIH) grants R01AG023731 and R21AG047400 to X.J.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Clayton DA. Replication of animal mitochondrial DNA. Cell. 1982;28:693–705. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt IJ, Lorimer HE, Jacobs HT. Coupled leading- and lagging-strand synthesis of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. Cell. 2000;100:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasukawa T, et al. Replication of vertebrate mitochondrial DNA entails transient ribonucleotide incorporation throughout the lagging strand. EMBO J. 2006;25:5358–5371. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lightowlers RN, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM. Exploring our origins--the importance of OriL in mtDNA maintenance and replication. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:1038–1039. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wanrooij S, et al. In vivo mutagenesis reveals that OriL is essential for mitochondrial DNA replication. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:1130–1137. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark-Walker GD. Evolution of mitochondrial genomes in fungi. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;141:89–127. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bullerwell CE, Leigh J, Forget L, Lang BF. A comparison of three fission yeast mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:759–768. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koszul R, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the pathogenic yeast Candida (Torulopsis) glabrata. FEBS Lett. 2003;534:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foury F, Roganti T, Lecrenier N, Purnelle B. The complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:325–331. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01467-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nosek J, Fukuhara H. NADH dehydrogenase subunit genes in the mitochondrial DNA of yeasts. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5622–5630. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5622-5630.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanc H, Dujon B. Replicator regions of the yeast mitochondrial DNA responsible for suppressiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3942–3946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Zamaroczy M, et al. The origins of replication of the yeast mitochondrial genome and the phenomenon of suppressivity. Nature. 1981;292:75–78. doi: 10.1038/292075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouchier C, Ma L, Creno S, Dujon B, Fairhead C. Complete mitochondrial genome sequences of three Nakaseomyces species reveal invasion by palindromic GC clusters and considerable size expansion. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9:1283–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen XJ, Clark-Walker GD. The petite mutation in yeasts: 50 years on. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;194:197–238. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ephrussi B, de Margerie-Hottinguer H, Roman H. Suppressiveness: A new factor in the genetic determinism of the synthesis of respiratory enzymes in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1955;41:1065–1071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.41.12.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitt ME, Clayton DA. Conserved features of yeast and mammalian mitochondrial DNA replication. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:769–774. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldacci G, Bernardi G. Replication origins are associated with transcription initiation sequences in the mitochondrial genome of yeast. EMBO J. 1982;1:987–994. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldacci G, Cherif-Zahar B, Bernardi G. The initiation of DNA replication in the mitochondrial genome of yeast. EMBO J. 1984;3:2115–2120. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graves T, Dante M, Eisenhour L, Christianson TW. Precise mapping and characterization of the RNA primers of DNA replication for a yeast hypersuppressive petite by in vitro capping with guanylyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1309–1316. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Dyck E, Clayton DA. Transcription-dependent DNA transactions in the mitochondrial genome of a yeast hypersuppressive petite mutant. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2976–2985. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goursot R, Mangin M, Bernardi G. Surrogate origins of replication in the mitochondrial genomes of ori-zero petite mutants of yeast. EMBO J. 1982;1:705–711. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fangman WL, Dujon B. Yeast mitochondrial genomes consisting of only A.T base pairs replicate and exhibit suppressiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7156–7160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fangman WL, Henly JW, Brewer BJ. RPO41-independent maintenance of rho− mitochondrial DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:10–15. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorimer HE, Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. A test of the transcription model for biased inheritance of yeast mitochondrial DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4803–4809. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenleaf AL, Kelly JL, Lehman IR. Yeast RPO41 gene product is required for transcription and maintenance of the mitochondrial genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3391–3394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers AM, Pape LK, Tzagoloff A. Mitochondrial protein synthesis is required for maintenance of intact mitochondrial genomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1985;4:2087–2092. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark-Walker GD, McArthur CR, Sriprakash KS. Location of transcriptional control signals and transfer RNA sequences in Torulopsis glabrata mitochondrial DNA. EMBO J. 1985;4:465–473. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekito T, Okamoto K, Kitano H, Yoshida K. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of Hansenula wingei reveals new characteristics of yeast mitochondria. Curr Genet. 1995;28:39–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00311880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langkjaer RB, Casaregola S, Ussery DW, Gaillardin C, Piskur J. Sequence analysis of three mitochondrial DNA molecules reveals interesting differences among Saccharomyces yeasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3081–3091. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson D. The curious history of yeast mitochondrial DNA. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:475–481. doi: 10.1038/nrg814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollenberg CP, Borst P, Thuring RW, van Bruggen EF. Size, structure and genetic complexity of yeast mitochondrial DNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;186:417–419. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(69)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petes TD, Byers B, Fangman WL. Size and structure of yeast chromosomal DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:3072–3076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.11.3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connor RM, McArthur CR, Clark-Walker GD. Closed-circular DNA from mitochondrial-enriched fractions of four petite-negative yeasts. Eur J Biochem. 1975;53:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Connor RM, McArthur CR, Clark-Walker GD. Respiratory-deficient mutants of Torulopsis glabrata, a yeast with circular mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid of 6 µm. J Bacteriol. 1976;126:959–968. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.2.959-968.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark-Walker GD, McArthur CR. Structure and functional relationships of mitochondrial DNAs from various yeasts. In: Bacila M, Horecker L, Stoppani AOM, editors. Biochemistry and Genetics of yeast: Pure and Applied Aspects. Academic Press; New York: 1978. pp. 255–271. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maleszka R, Skelly PJ, Clark-Walker GD. Rolling circle replication of DNA in yeast mitochondria. EMBO J. 1991;10:3923–3929. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bendich AJ. Reaching for the ring: the study of mitochondrial genome structure. Curr Genet. 1993;24:279–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00336777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wesolowski M, Fukuhara H. Linear mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid from the yeast Hansenula mrakii. Mol Cell Biol. 1981;1:387–393. doi: 10.1128/mcb.1.5.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovac L, Lazowska J, Slonimski PP. A yeast with linear molecules of mitochondrial DNA. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197:420–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00329938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukuhara H, et al. Linear mitochondrial DNAs of yeasts: frequency of occurrence and general features. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2309–2314. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dinouel N, et al. Linear mitochondrial DNAs of yeasts: closed-loop structure of the termini and possible linear-circular conversion mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2315–2323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nosek J, Tomaska L, Fukuhara H, Suyama Y, Kovac L. Linear mitochondrial genomes: 30 years down the line. Trends Genet. 1998;14:184–188. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nosek J, Tomaska L. Mitochondrial genome diversity: evolution of the molecular architecture and replication strategy. Curr Genet. 2003;44:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s00294-003-0426-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomaska L, Nosek J, Fukuhara H. Identification of a putative mitochondrial telomere-binding protein of the yeast Candida parapsilosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3049–3056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fricova D, et al. The mitochondrial genome of the pathogenic yeast Candida subhashii: GC-rich linear DNA with a protein covalently attached to the 5' termini. Microbiology. 2010;156:2153–2163. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038646-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kosa P, Valach M, Tomaska L, Wolfe KH, Nosek J. Complete DNA sequences of the mitochondrial genomes of the pathogenic yeasts Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis: insight into the evolution of linear DNA genomes from mitochondrial telomere mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2472–2481. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valach M, et al. Evolution of linear chromosomes and multipartite genomes in yeast mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4202–4219. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bochman ML, Sabouri N, Zakian VA. Unwinding the functions of the Pif1 family helicases. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lucas P, Lasserre JP, Plissonneau J, Castroviejo M. Absence of accessory subunit in the DNA polymerase gamma purified from yeast mitochondria. Mitochondrion. 2004;4:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han Z, Stachow C. Analysis of Schizosaccharomyces pombe mitochondrial DNA replication by two dimensional gel electrophoresis. Chromosoma. 1994;103:162–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00368008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Preiser PR, et al. Recombination associated with replication of malarial mitochondrial DNA. EMBO J. 1996;15:684–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fangman WL, Henly JW, Churchill G, Brewer BJ. Stable maintenance of a 35-base-pair yeast mitochondrial genome. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1917–1921. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.5.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bastia D, Sueoka N. Studies on the late replication of phage lambda: rolling-circle replication of the wild type and a partially suppressed strain, Oam29 Pam80. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:305–320. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shutt TE, Gray MW. Bacteriophage origins of mitochondrial replication and transcription proteins. Trends Genet. 2006;22:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacAlpine DM, Perlman PS, Butow RA. The high mobility group protein Abf2p influences the level of yeast mitochondrial DNA recombination intermediates in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6739–6743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerhold JM, Aun A, Sedman T, Joers P, Sedman J. Strand invas ion structures in the inverted repeat of Candida albicans mitochondrial DNA reveal a role for homologous recombination in replication. Mol Cell. 2010;39:851–861. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gerhold JM, et al. Replication intermediates of the linear mitochondrial DNA of Candida parapsilosis suggest a common recombination based mechanism for yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:22659–22670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.552828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen XJ, Guan MX, Clark-Walker GD. MGM101, a nuclear gene involved in maintenance of the mitochondrial genome in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3473–3477. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuo XM, Clark-Walker GD, Chen XJ. The mitochondrial nucleoid protein, Mgm101p, of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is involved in the maintenance of rho+ and ori/rep-devoid petite genomes but is not required for hypersuppressive rho− mtDNA. Genetics. 2002;160:1389–1400. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.4.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark-Walker GD. In vivo rearrangement of mitochondrial DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8847–8851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ling F, Hori A, Shibata T. DNA recombination-initiation plays a role in the extremely biased inheritance of yeast rho− mitochondrial DNA that contains the replication origin ori5. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1133–1145. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00770-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuo X, Xue D, Li N, Clark-Walker GD. A functional core of the mitochondrial genome maintenance protein Mgm101p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae determined with a temperature-conditional allele. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7:131–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mbantenkhu M, et al. Mgm101 is a Rad52-related protein required for mitochondrial DNA recombination. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42360–42370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.307512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nardozzi JD, Wang X, Mbantenkhu M, Wilkens S, Chen XJ. A properly configured ring structure is critical for the function of the mitochondrial DNA recombination protein, Mgm101. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37259–37268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meeusen S, Nunnari J. Evidence for a two membrane-spanning autonomous mitochondrial DNA replisome. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:503–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ling F, Shibata T. Recombination-dependent mtDNA partitioning: in vivo role of Mhr1p to promote pairing of homologous DNA. EMBO J. 2002;21:4730–4740. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shibata T, Ling F. DNA recombination protein-dependent mechanism of homoplasmy and its proposed functions. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lewis SC, et al. A rolling circle replication mechanism produces multimeric lariats of mitochondrial DNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pohjoismaki JL, et al. Human heart mitochondrial DNA is organized in complex catenated networks containing abundant four-way junctions and replication forks. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21446–21457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ducani C, Bernardinelli G, Hogberg B. Rolling circle replication requires single-stranded DNA binding protein to avoid termination and production of double-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:10596–10604. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prasai K, Robinson LC, Scott RS, Tatchell K, Harrison L. Evidence for double-strand break mediated mitochondrial DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]