Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to examine the association between verbal learning, fluency, and processing speed with anxious-depression symptomatology among diverse Hispanic/Latinos. We hypothesize an inverse association of anxious-depression with neurocognition among Hispanic/Latinos of different heritage.

Design

Data are from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). The sample included 9,311participants aged 45–74 years (Mean:56.6). A latent class analysis of items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies for Depression (CESD-10 item) and the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory was used to derive an anxious-depression construct. Neurocognitive measures included scores on the Brief Spanish English Verbal Learning Test (B-SEVLT learning and recall trials), Word Fluency (WF), Digit Symbol Substitution (DSS) test and a Global Cognitive Score (GCS). We fit survey linear regression models to test the associations between anxious-depression symptomatology and cognitive function.

Results

Among men, 71% reported low, 24% moderate, and 5% high ADS. Among women, 54.7% reported low, 33.2% moderate, and 12.2% high ADS. After controlling for age, sex, weight, socio-demographic characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, and antidepressant use, we found significant inverse associations between moderate and high anxious-depression (ref:low) with B-SEVLT learning and recall, DSST and GCS (p-values≤0.05). Moderate, but not high, anxious-depression was inversely associated with WF (p-value<0.05).

Conclusion

Increased anxious-depression symptomatology is associated with decreased neurocognitive function among Hispanic/Latinos. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish temporality and infer if negative emotional symptoms precede cognitive deficits.

Introduction

Depression often coexists with symptoms of anxiety, and it has been argued that anxious-depression symptomatology (ADS) may form a distinct construct and syndrome (Camacho et al., 2015; Ionescu DF, Niciu MJ, Henter ID, & Zarate CA, 2013; Katon W & Roy-Byrne PP, 1991; Kessler RC et al., 1994). Despite being commonly encountered by practicing clinicians, the anxious depression construct is also frequently missed in clinical settings, and has not been widely studied among middle-aged and older Hispanics/Latinos (Jeste, Hays, & Steffens, 2006; Lenze et al., 2001; Olariu et al., 2015; Zvolensky et al., 2016). Both anxiety and depression have been linked to lower cognitive function (Austin MP, Mitchell P, & Goodwin GM, 2001) and cognitive disorders (Alexopoulos GS et al., 1997; González HM, Tarraf W, Whitfield K, & Gallo JJ, 2012), however there is limited research on the associations between anxious-depression symptomatology and cognitive function in high disparity groups (e.g. Hispanics/Latinos). This study addresses this gap using a well-characterized community-based sample of middle-aged and older Hispanic/Latinos.

We previously examined anxiety and depressive symptoms among participants from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) and found that Hispanic/Latinos have a high prevalence (30%) of anxious-depression symptomatology (Camacho et al., 2015). Differential anxiety and depressive symptoms based on Hispanic/Latino heritage has advocated for more research given the important cross-cultural psychiatric implications among Hispanics/Latinos from different heritage groups (Lewis-Fernández et al., 2010).

We used data from the baseline visit of HCHS/SOL (Daviglus ML et al., 2012) the largest and most recent cohort of Hispanic/Latinos from diverse heritage groups, to examine the association between ADS and neurocognitive (NC) functioning. We predicted inverse associations between ADS and NC functioning, consistent across multiple cognitive domains. Based on our previous finding of higher rates of anxious-depression symptomatology among Puerto Ricans compared to individuals of Mexican heritage (Camacho et al., 2015), we expected these associations to vary by Hispanic/Latino heritage group.

Methods

Data

The Hispanic Community Health Study / Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) is a multisite (Bronx,NY; Chicago,IL; Miami,FL; San Diego,CA) cohort study. Complex sampling procedures that have been detailed elsewhere,(Daviglus ML et al., 2012; Lavange LM et al., 2010; Sorlie et al., 2010) were designed and executed to ensure appropriate generalizability to the target populations. The HCHS/SOL aims to identify risk and protective factors for chronic disease among diverse Hispanic/Latino heritage groups living across the United States. The cohort consists of 16,415 men and women aged 18 to 74 years at the time of recruitment (2008–2011). This population includes first through third generation participants self-identifying as one of six Hispanic/Latino heritage groups including Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Dominican, Central and South-American. In-clinic visits and standardized questionnaires were used to collect detailed socio-demographic, socio-cultural, and health information (Daviglus ML et al., 2012; Sorlie et al., 2010). The HCHS/SOL was approved by the Institutional Review Board of all participating study sites.

The current study focused on participants 45-years and older that agree to take the study’s neurocognitive module (n=9,623). Our analytical sample consisted of 9,183 participants ages 45–74 (Mean:56.6 years). We excluded n=321 participants who had missing data on any of the model covariates and n=128 participants with missing data on anxiety and depressive symptoms. Excluded participants did not differ from those included in our analytical sample in age (p=0.60) or sex (p=0.58). Methods appropriate for subpopulation analyses under complex sampling design were used to generate all reported parameter estimates (Heeringa, West, & Berglund, 2010).

Neurocognitive outcomes

A battery of four cognitive tests and a global cognition score were administered.

First, we used the Brief Spanish English Verbal Learning Test (B-SEVLT), a measure of memory and learning, abbreviated to include three instead of five of the 15-word SEVLT List A learning trials to reduce participant burden (González et al., 2015). This test has been validated both in English and Spanish (González HM, Mungas D, & Haan MN, 2002). A detailed description of the SEVLT including the translation and back translation has been published elsewhere (González HM et al., 2002). Learning was assessed using the sum of the total items of List A recalled across the three learning trials (Sum B-SEVLT), and memory was assessed using participants’ scores on the delayed trial (González et al., 2015).

Second, we used Word Fluency Test (WF) to assess semantic memory and fluency. Two letters, F and A, were used and the letter S was omitted. The letters S and C are often pronounced similarly in Spanish, making the use of the letter S a potential source of language bias (González et al., 2015). Participants were asked to orally generate as many unique words beginning with a specified letter (F or A; excluding proper nouns and conjugated words) as possible within 60 seconds. The sum of correctly generated words with both letters served as the dependent measure.

Third, the Digit Symbol Subtest (DSS) was administered according to published procedures (Wechler D, 1981). As a subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised, the DSS measures processing speed and executive processes (Joy S, Fein D, & Kaplan E, 2003; Wechler D, 1981). Participants were asked to rapidly copy as many symbols corresponding to numbers as possible, without error, within 90 seconds. The sum of correctly produced stimuli served as the dependent variable.

Finally, we considered a Global Cognitive Score, which was operationalized as the average of the z-scores across these four tests (Callahan, Unverzagt, Hui, Perkins, & Hendrie, 2002; González et al., 2015).

With the exception of the B-SELVT (already available in Spanish), all neurocognitive tests were translated to Spanish, and results back translated from Spanish to English. Validation and translation procedures are described elsewhere (González HM et al., 2002). The neurocognitive tests were administered in the participants' preferred language during face-to-face interviews by trained research staff who were supervised by doctorate-level, licensed clinical neuropsychologists (González et al., 2015).

Anxious-Depression Symptoms

An anxious-depression construct was derived from latent class analysis of items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies for Depression (CESD-10 item) and the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Camacho et al., 2015). A three-class model resulted in a high anxious-depressed group (10% of sample), a moderate anxious-depressed group (30% of sample) and a low anxious-depressed group (60% of the target population of sample). This approach has previously generated consistent characteristics of anxious-depression latent classes, similarly typified as high, moderate, and low, and provided support for our dimensional operationalization (Camacho, 2013; Camacho et al., 2015; Roesch SC, Villodas M, & Villodas F, 2010). The resulting classes were non-separable and highly correlated within the anxious-depression construct. Item distributions across the three derived classes are presented in Supplemental Figure 1.

Covariates

We considered several covariates in our adjusted models. Socio-demographic characteristics included age, sex, participant language of preference, income (<$20,000; $20,001–50,000; >$50,000; unreported), and educational attainment(<high school; high school graduate and >high school).Hispanic/Latino heritage group was measured using 7 categories based on respondent self-identification as: “Dominican or Dominican descent, Central-American or Central-American descent, Cuban or Cuban descent, Mexican or Mexican descent, Puerto Rican or Puerto Rican descent, South-American or South-American descent, More than one heritage, Other.” Cardiovascular factors included presence (Y/N) of diabetes, hypertension, heart attack and heart failure. We also adjusted for BMI.

Statistical Analyses

First, we generated descriptive statistics for our analytical sample (Table 1). Second, we used survey linear regression to examine bivariate associations between anxious-depression and our cognitive function domains (Table 2). Third, we fit two adjusted models for each cognitive outcome to examine attenuations in the bivariate associations due to 1) age, sex, and education; and 2) cardiovascular risks/factors and controls (Table 2). For each model we report the estimates beta coefficient, survey adjusted standard error for correct inferences, and two tailed t-test p-values for statistically significant associations (i.e. p<0.05).To facilitate the interpretation of our results, we calculated and plotted the estimated unadjusted and adjusted average marginal effects and their 95% confidence intervals in Figure 1. Fourth, to test for differential associations by sex and background groups, we refitted the fully adjusted models as described above and included Hispanic/Latino heritage and sex by anxious-depression interactions. We used survey adjusted Wald-tests to examine the statistical significance of the interaction effects. Additionally, group specific marginal effects and their 95% confidence intervals are plotted in Figures2 and 3, and marginal contrasts are calculated and included in Supplemental Tables1 and 2. LCA analyses were conducted in Mplus version 7.2 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA), and all other analyses were done in STATA version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All analyses accounted for the complex design of the HCHS/SOL including clustering, stratification, and adjustment for sampling probability and non-response.(Daviglus ML et al., 2012; Lavange LM et al., 2010; Sorlie et al., 2010)

Table 1.

Prevalence (%) of anxious-depression symptomatology among participants (45–75 years old) in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL).

| Low | Moderate | High | Pearson χ2/F-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Latino Background | p<0.001 | |||

| Dominican | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Central | 63.9 | 29.5 | 6.6 | |

| Cuban | 61.0 | 29.0 | 10.0 | |

| Mexican | 68.6 | 25.9 | 5.5 | |

| Puerto-Rican | 53.0 | 33.1 | 13.9 | |

| South American | 66.6 | 26.8 | 6.6 | |

| Other | 61.3 | 31.4 | 7.3 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Sex | p<0.001 | |||

| Male | 71.6 | 23.3 | 5.1 | |

| Female | 55.1 | 33.2 | 11.8 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Education | p<0.001 | |||

| Less than HS | 56.8 | 32.2 | 11.0 | |

| HS or Equivalent | 61.3 | 30.1 | 8.7 | |

| More than HS | 69.1 | 24.4 | 6.5 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Income | p<0.001 | |||

| <=$20,00 | 54.3 | 33.5 | 12.2 | |

| $20,001- | 70.5 | 24.2 | 5.4 | |

| >=$50,00 | 81.2 | 16.6 | 2.1 | |

| Not Reported | 52.8 | 35.8 | 11.5 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Language | p<0.001 | |||

| Spanish | 58.6 | 28.6 | 12.8 | |

| English | 63.2 | 28.7 | 8.1 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Nativity | p<0.001 | |||

| Foreign Born | 63.1 | 28.6 | 8.3 | |

| US Born | 57.6 | 29.8 | 12.5 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Hypertension | P = 0.00 | |||

| No | 64.9 | 27.3 | 7.8 | |

| Yes | 60.1 | 30.2 | 9.7 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| CHD/Angina | P = 0.0000 | |||

| No | 63.9 | 27.9 | 8.3 | |

| Yes | 51.3 | 36.2 | 12.6 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Stroke/TIA | p=0.005 | |||

| No | 63.1 | 28.3 | 8.6 | |

| Yes | 51.4 | 37.6 | 11.0 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Diabetes ADA | p=0.01 | |||

| No | 63.9 | 27.9 | 8.2 | |

| Yes | 59.1 | 30.8 | 10.1 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Heart Attack | p<0.001 | |||

| No | 62.8 | 28.8 | 8.4 | |

| Yes | 56.0 | 27.5 | 16.4 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Heart Failure | p<0.001 | |||

| No | 63.1 | 28.4 | 8.5 | |

| Yes | 45.0 | 38.2 | 16.8 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| BMI | p<0.001 | |||

| Underweight | 74.4 | 15.1 | 10.5 | |

| Normal | 62.5 | 29.3 | 8.2 | |

| Overweight | 66.3 | 27.0 | 6.7 | |

| Obese | 58.9 | 30.3 | 10.9 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

| Antidepressants | p<0.001 | |||

| No | 65.3 | 27.4 | 7.4 | |

| Yes | 35.4 | 42.0 | 22.5 | |

| Total | 62.6 | 28.7 | 8.7 | |

Table 2.

Associations between anxious-depression symptomatology and neurocognitive function. Results are from survey linear regression models using data from participants ages 45–74 years from the Hispanic Community Health Study (HCHS/SOL).

| Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| SEVLT Sum | |||

|

|

|||

| β/(se) | β/(se) | β/(se) | |

|

|

|||

| ADS✢ | |||

| Low | ref | ref | ref |

| Medium | −0.26*** (0.05) | −0.29*** (0.04) | −0.18*** (0.04) |

| High | −0.51*** (0.06) | −0.59*** (0.06) | −0.40*** (0.06) |

| SEVLT Recall | |||

|

|

|||

| ADS | |||

| Low | ref | ref | ref |

| Medium | −0.24*** (0.04) | −0.27*** (0.04) | −0.17*** (0.04) |

| High | −0.55*** (0.07) | −0.63*** (0.06) | −0.45*** (0.07) |

| Word Fluency | |||

|

|

|||

| ADS | |||

| Low | ref | ref | ref |

| Medium | −0.25*** (0.05) | −0.20*** (0.04) | −0.10* (0.04) |

| High | −0.36*** (0.11) | −0.29** (0.11) | −0.11 (0.10) |

| Digit Symbol Substitution Test | |||

|

|

|||

| ADS | |||

| Low | ref | ref | ref |

| Medium | −0.33*** (0.05) | −0.27*** (0.03) | −0.19*** (0.03) |

| High | −0.40*** (0.08) | −0.34*** (0.07) | −0.26*** (0.06) |

| Global Cognition | |||

|

|

|||

| ADS | |||

| Low | ref | ref | ref |

| Medium | −0.26*** (0.03) | −0.25*** (0.03) | −0.16*** (0.03) |

| High | −0.45*** (0.06) | −0.46*** (0.06) | −0.31*** (0.05) |

P<0.001

P<0.01

P<0.05

Anxious Depression Symptomatology

Model 0 includes crude associations; Model 1 adjusts for age, sex, and education; Model 2 is a fully adjusted model and includes M1 covariates + Latino background, income, language preference, nativity, hypertension, CHD/angina, stroke/TIA, diabetes, heart attack, heart failure, BMI groupings, and antidepressant medications use.

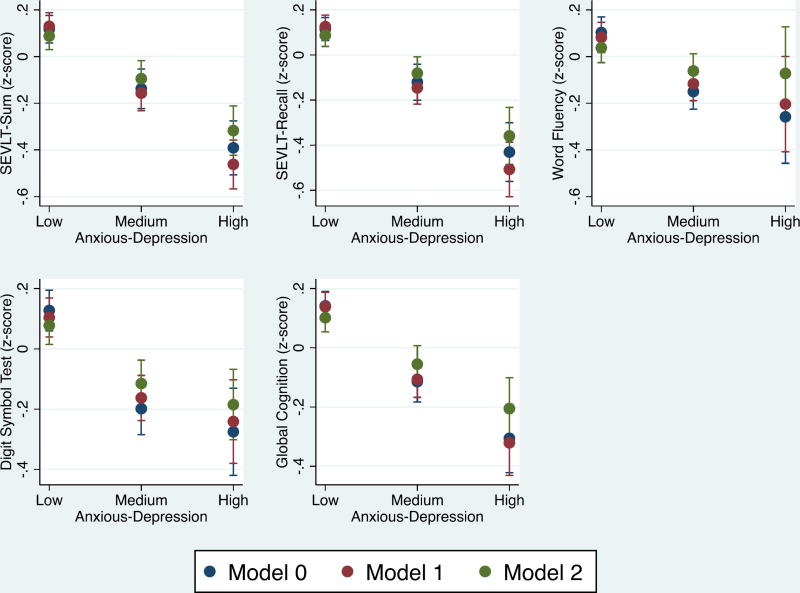

Figure 1.

Marginal effects differences of anxious-depression classes with the different cognitive tests used among Hispanic/Latinos of different heritage.

Model 0: includes crude associations; Model 1: adjusts for age, sex, and education; Model 2: is a fully adjusted model and includes M1 covariates + Latino background, income, language preference, nativity, hypertension, CHD/angina, stroke/TIA, diabetes, heart attack, heart failure, BMI groupings, and antidepressant medications use. Estimated marginal means are based on survey linear regression models.

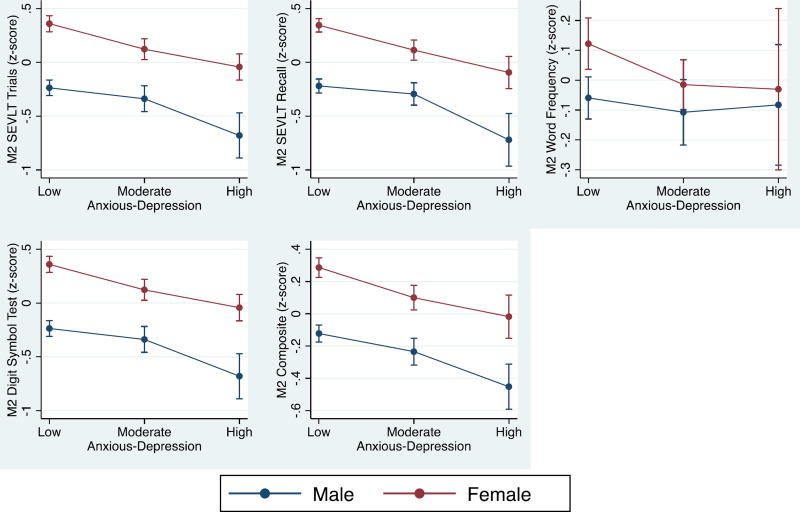

Figure 2.

Interaction between sex and groups of anxious-depression symptomatology.

Estimated marginal means are based on survey linear regression models adjusted for age, Latino background, income, language preference, nativity, hypertension, CHD/angina, stroke/TIA, diabetes, heart attack, heart failure, BMI groupings, and antidepressant medications use.

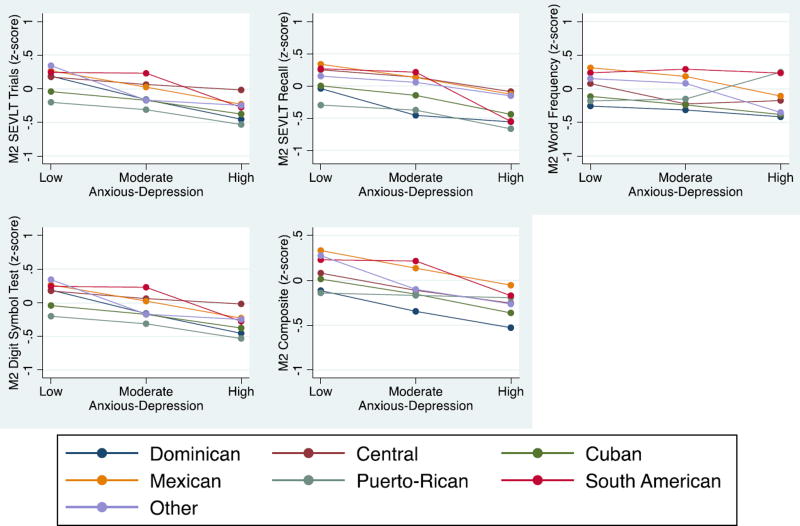

Figure 3.

Interaction between Hispanic/Latinos backgrounds and groups of anxious-depression.

Estimated marginal means are based on survey linear regression models adjusted for age, sex, income, language preference, nativity, hypertension, CHD/angina, stroke/TIA, diabetes, heart attack, heart failure, BMI groupings, and antidepressant medications use.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the sample. Among men 71.6% reported low, 23.3% moderate, and 5.1% high ADS. Among women, 55.1% reported low, 33.2% moderate and 11.8% high ADS. In this older middle age and older sample, we also found significant Hispanic/Latino heritage differences in ADS distribution; Mexicans reported the lowest prevalence of high ADS (5.5%) and Puerto Ricans reported the highest (13.9%) which is consistent with our other report.(Camacho et al., 2015) We also found significant variations by education, income, language, and nativity status that pointed to higher prevalence of ADS among socioeconomically disadvantaged, Spanish speaking, and US born respondents. Finally, we found consistent evidence for comorbid high ADS and our considered cardiovascular risk factors and diseases.

Crude Associations

We found inverse associations between high anxious-depression symptomatology and lower neurocognitive function that were consistent across the five considered NC indicators (Table 2). Compared to the low anxious-depression reference group, participants in the moderate anxious-depression group had cognitive scores that were 0.26, 0.24, 0.25, 0.33, and 0.26 standard deviations (SD) lower on the SEVLT-Sum, SEVLT-recall, WF, DSS, and GC, respectively (all p<0.001). Relative to same reference group, participants in the high anxious-depression group had cognitive scores that were 0.51, 0.55, 0.36, 0.40, and 0.45 standard deviations (SD) lower on the SEVLT-Sum, SEVLT-recall, WF, DSS, and Global Cognitive score respectively (all p<0.001).

Adjusted Models

All negative associations between anxious-depression and neurocognition remained statistically evident in age, sex, and education adjusted models (Table 2). The inverse associations between anxious-depression group and learning (SEVLT-Sum) and memory (SEVLT-recall) scores were accentuated by about 12% and 15% for the moderate and high ADS groups. The associations between anxious-depression group and the WF and DSS scores, however, were attenuated by about 20% for both the moderate and high anxious-depression groups. Age, sex, and education adjustment had no noticeable effect on the reported significant crude associations between anxious-depression groups and global cognition. Additional adjustment for the CV risks and disease factors uniformly attenuated the reported associations between anxious-depression and NC function compared to the age, sex, and education adjusted models. There was an average of a 38% attenuation of the coefficients of the moderate anxious-depression group (ref: low) for the SELVT-Sum, SEVLT-recall, WF, DSS, and Global Cognitive score; the inverse association remained significant. For the high anxious-depression group (ref: low) there was an average of a 30% attenuation for the SELVT-Sum, SEVLT-recall, DSS, and Global Cognitive score; the inverse association remained significant. The coefficient for the high anxious-depression group (ref: low) was completely attenuated (p>0.05) with respect to the WF test. Table 2 summarized these findings.

Interaction Models

We found no evidence to support either sex or Hispanic/Latino heritage as modifying factors in the reported associations between anxious-depression group and cognitive function. The tested interactions across the five NC outcomes were not statistically significant. The tested group specific marginal differences for sex and Latino backgrounds are presented in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. The estimated average marginal effects by sex and Latino background and their 95% confidence intervals are presented in Figures 2 and 3.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we found a significant inverse association of high and moderate anxious-depression class with neurocognitive function. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated the anxious-depression construct and neurocognitive function among diverse middle-aged and older Hispanics/Latinos. High independent levels of anxiety and depression symptoms have been reported to be associated with cognitive decline in the elderly (Balash et al., 2013; Bierman, Comijs, Jonker, & Beekman, 2007; Lenze et al., 2001; Lenze et al., 2000; Wetherell, Reynolds, Gatz, & Pedersen, 2002). One study (Lopez et al., 2003) reported depressive symptoms as an early marker of cognitive change, while others have found no associations (Bierman et al., 2007; Bravi, Calvani, & Carta, 1996; Li, Meyer, & Thornby, 2001; Lyketsos et al., 2002). Our results emphasize how elevated combined anxious-depression symptomatology is associated with poorer cognitive performance among diverse Hispanics/Latinos. To our knowledge, this is the first study that examined ADS and neurocognition among middle age and older Hispanics/Latinos adding an important contribution to the literature.

Although our results showed that individuals of Puerto Rican heritage had the highest inverse association between anxious-depression and cognitive function, the magnitude of the inverse association applies across all groups of Hispanic/Latinos of different heritage. Except for Word Fluency among Hispanic/Latinos reporting high anxious-depression, all the other inverse associations between moderate and high anxious-depression remained significant with cognition after controlling for demographics, income, education and cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension and coronary heart disease. These results emphasize how elevated anxious-depression which is very common among Hispanic/Latinos,(Camacho et al., 2015; Lewis-Fernández et al., 2002; Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2014) affect cognitive function.

Our results showed that the inverse association of high and moderate anxious-depression with neurocognition is uniform among the different Hispanic/Latino heritage groups. How this association of anxious-depression symptomatology with neurocognition affects other ethnic groups remains to be studied. Furthermore, future studies looking at the association of anxious-depression and neurocognition need to be linked to a functional outcome reported by the patient or caregiver. This is an important consideration since cognition and function have are associated with cultural and socioeconomic status (Evans et al., 1993).

It is important to consider if premorbid moderate to high levels of anxious-depression symptomatology affects the participant's performance in the neurocognitive tests. A longitudinal path-analyses study tested the bidirectional association between neurocognition and depressive symptoms (Perrino, Mason, Brown, Spokane, & Szapocznik, 2008). In their study, Perrino et al. found a significant association between cognition and further development of cognitive decline but did not find a significant bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and cognitive decline over a 3 year period (Perrino et al., 2008). To our knowledge there are no studies examining the bidirectional association between anxious-depression and neurocognitive function. Our study is a preliminary report in that directions, considering that individuals with combined anxiety and depressive symptomatology face greater disability, are frequently undertreated and have a greater proportion of chronic cardiometabolic diseases (Camacho et al., 2015; Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2014).

A previous study from the HCHS/SOL reported that there is an association between anxiety and depressive symptoms with cardiovascular risk factors (Castañeda et al., 2016). Additionally, one study found that 43% of participants with cognitive decline had a comorbid cardiometabolic disease such as hypertension or diabetes (Haan et al., 2003). Our study is the first to report an association of the commonly encountered anxious-depression construct with poor neurocognition function among diverse Hispanic/Latinos independent from existing socio-economic and cardiovascular risk factors.

These findings have important public health implications due to the high prevalence of anxiety, depressive symptoms and cardiovascular risk factors among Hispanics/Latinos. The literature has described that symptoms of depression and cognitive decline are commonly encountered in clinical settings and are frequently untreated (Artero, Touchon, & Ritchie, 2001; Perrino et al., 2008). Further, a previous HCHS/SOL study found a significant association between high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms and under treatment with antidepressants among participants with several cardiovascular risk factors (Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2014). Our results further suggest the importance of early identification and treatment of anxious-depression in conjunction with cardio-metabolic risk factors to reduce the burden associated with poor cognitive function and prevention of further cognitive decline.

Is important to remember that anxious-depression symptomatology is common among Hispanic/Latinos (Camacho et al., 2015). Based on the significant association of anxious-depression with poor neurocognitive function, our findings suggest that is important to raise awareness about the burden of untreated anxious-depression symptomatology and the individual’s ability to function. This burden affects both the individual as well as the family members that traditionally take care of their older relatives in the Hispanic/Latino culture (Neary & Mahoney, 2005). Our results further support the need for longitudinal studies to determine the causal association between anxious-depression symptomatology and cognitive decline among Hispanic/Latinos from different heritage groups.

Caution is warranted in interpreting our results due to limitations associated with the sample, study methods, and design. First, the sample is not nationally representative of Hispanics/Latinos living in the US. Rather, it is representative of the Hispanic/Latino population residing in the four study sites. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow causal inferences. Third, structured clinical interviews were not used therefore formal diagnoses were not made. Despite this limitation, our study has the strength of the sample size, the incorporation of Hispanics from different heritage and use of comprehensive battery of NC tests. Additionally, the measurement of the anxious-depression construct uses a latent class approach that minimizes measurement error.

In conclusion, anxious-depression symptomatology is common and significantly associated with poor cognitive function among diverse Hispanic/Latinos independent of socioeconomic background and cardiovascular risk factors. Additional research is needed to address treatment and interventions to reduce the burden associated with anxious-depression symptomatology and cognitive function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos, which was supported by contracts from the NHLBI to the University of North Carolina (N01-HC65233), University of Miami (N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (N01-HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01-HC65237). Drs. González, Daviglus, Gallo, Kaplan, and Tarraf also receive support from the National Institute of Aging (AG48642).The following Institutes/Centers/Offices contribute to the HCHS/SOL through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Office of Dietary Supplements. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank the participants and staff of the HCHS/SOL for their important contributions.

Special thanks to Alan Conceicao for the editorial support for this manuscript.

References

- Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kakuma T, Silbersweig D, Charlson M. Clinically defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(4):562–565. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artero S, Touchon J, Ritchie K. Disability and mild cognitive impairment: a longitudinal population-based study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16(11):1092–1097. doi: 10.1002/gps.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MP, Mitchell P, Goodwin GM. Cognitive deficits in depression: Possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178(3):200–206. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balash Y, Mordechovich M, Shabtai H, Giladi N, Gurevich T, Korczyn A. Subjective memory complaints in elders: depression, anxiety, or cognitive decline? Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2013;127(5):344–350. doi: 10.1111/ane.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman E, Comijs H, Jonker C, Beekman A. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in the course of cognitive decline. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2007;24(3):213–219. doi: 10.1159/000107083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravi D, Calvani M, Carta A. Longitudinal Assessment of Symptoms of Depression, Agitation, and Psychosis in 18 1 Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease. Age (years) 1996;51(65):41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-Item Screener to Identify Cognitive Impairment Among Potential Subjects for Clinical Research. Medical Care. 2002;40(9):771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Á. Is anxious-depression an inflammatory state? Medical Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):577–581. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Á, Gonzalez P, Buelna C, Emory KT, Talavera GA, Castañeda SF, Roesch SC. Anxious-depression among Hispanic/Latinos from different backgrounds: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Soc Psychiatry and Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(11):1669–1677. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1120-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda SF, Buelna C, Giacinto RE, Gallo LC, Sotres-Alvarez D, Gonzalez P, Talavera GA. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and psychological distress among Hispanics/Latinos: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Preventive Medicine. 2016;87:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.032. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, Stamler J. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308(17):1775–1785. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DA, Beckett LA, Albert MS, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Funkenstein HH, Taylor JO. Level of education and change in cognitive function in a community population of older persons. Annals of Epidemiology. 1993;3(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90012-s. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/1047-2797(93)90012-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González HM, Mungas D, Haan MN. A verbal learning and memory test for English- and Spanish-speaking older Mexican-American adults. Clin Neuropsychol. 2002;16(4):439–451. doi: 10.1076/clin.16.4.439.13908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González HM, Tarraf W, Whitfield K, Gallo JJ. Vascular depression prevalence and epidemiology in the United States. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;(46):4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González HM, Tarraf W, Gouskova N, Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Davis SM, Mosley TH. Neurocognitive Function Among Middle-aged and Older Hispanic/Latinos: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2015;30(1):68–77. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A, Jagust WJ. Prevalence of Dementia in Older Latinos: The Influence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Stroke and Genetic Factors. Journal of the American geriatrics society. 2003;51(2):169–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied survey data analysis. CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu DF, Niciu MJ, Henter ID, Zarate CA. Defining anxious depression: a review of the literature. CNS Spectr. 2013:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1092852913000114. Mar 14 Epub Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste ND, Hays JC, Steffens DC. Clinical correlates of anxious depression among elderly patients with depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;90(1):37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.10.007. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy S, Fein D, Kaplan E. Decoding Digit Symbol: Speed, Memory, and Visual Scanning. Assessment. 2003;10(1):56–65. doi: 10.1177/0095399702250335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Roy-Byrne PP. Mixed anxiety and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(3):337–345. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman St, AL E. Lifetime and 12-moth prevalance of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, Avilés-Santa LM, Kaplan RC, Barnhart J, Elder JP. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Shear MK, Alexopoulos GS, Frank E, Reynolds CF. Comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorders in later life. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;14(2):86–93. doi: 10.1002/da.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Shear MK, Schulberg HC, Dew MA, Begley AE, Charles F, Reynolds I. Comorbid Anxiety Disorders in Depressed Elderly Patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):722–728. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernández R, Guarnaccia P, Martínez I, Salmán E, Schmidt A, Liebowitz M. Comparative Phenomenology of Ataques de Nervios, Panic Attacks, and Panic Disorder. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2002;26(2):199–223. doi: 10.1023/a:1016349624867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernández R, Hinton DE, Laria AJ, Patterson EH, Hofmann SG, Craske MG, Liao B. Culture and the anxiety disorders: recommendations for DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(2):212–229. doi: 10.1002/da.20647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YS, Meyer JS, Thornby J. Longitudinal follow-up of depressive symptoms among normal versus cognitively impaired elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16(7):718–727. doi: 10.1002/gps.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Becker JT, Sweet RA, Klunk W, Kaufer DI, Saxton J, DeKosky ST. Psychiatric symptoms vary with the severity of dementia in probable Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2003;15(3):346–353. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–1483. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary SR, Mahoney DF. Dementia Caregiving: The Experiences of Hispanic/Latino Caregivers. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2005;16(2):163–170. doi: 10.1177/1043659604273547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olariu E, Forero CG, Castro-Rodriguez JI, Rodrigo-Calvo MT, Álvarez P, Martín-López LM, Alonso J. Detection of Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care:A Meta-Analysis of Assisted and Unassisted Diagnoses. Depression and Anxiety. 2015;32(7):471–484. doi: 10.1002/da.22360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Mason CA, Brown SC, Spokane A, Szapocznik J. Longitudinal Relationships Between Cognitive Functioning and Depressive Symptoms Among Hispanic Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63(5):P309–P317. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.5.P309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch SC, Villodas M, Villodas F. Latent class/profile analysis in maltreatment research: A commentary on Nooner et al., Pears et al, and looking beyond. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie PD, Avilés-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, Heiss G. Design and Implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20(8):629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassertheil-Smoller S, Arredondo EM, Cai J, Castaneda SF, Choca JP, Gallo LC, Zee PC. Depression, anxiety, antidepressant use, and cardiovascular disease among Hispanic men and women of different national backgrounds: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Annal Epidemiol. 2014;24(11):822–830. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.09.003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechler D. WAIS-R Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell JL, Reynolds CA, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. Anxiety, cognitive performance, and cognitive decline in normal aging. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(3):P246–P255. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.p246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Paulus DJ, Bakhshaie J, Garza M, Ochoa-Perez M, Medvedeva A, Schmidt NB. Interactive effect of negative affectivity and anxiety sensitivity in terms of mental health among Latinos in primary care. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.