Abstract

Sleep disturbance symptoms are common in persons living with Alzheimer disease (AD). However little is known about the impact of sleep disturbance symptoms in patients living with AD on caregiver burden and quality of life (QOL). The aims of this study were to determine the prevalence of symptoms of disturbed sleep in patients with AD, identify the care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms that predict caregiver burden and QoL, and determine how care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms compare to other caregiver and patient characteristics when predicting caregiver QoL. Caregiver burden was assessed using the Screen for Caregiver Burden. Sixty percent of the care-recipients had at least one sleep symptom. In 130 caregiver/patient dyads, nocturnal awakenings, nocturnal wandering, and snoring predicted caregiver burden. Multivariate modeling demonstrated that caregiver burden, caregiver physical and mental health, and caregiver depression were predictors of overall caregiver QoL. Treating disturbed sleep in care-recipients and caregiver mental health symptoms could have important public health impact by improving the lives of the caregiving dyad.

Keywords: dementia, wandering, depression, quality of life, burden

Introduction

Persons living with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have disrupted sleep, with prevalence rates as high as 71%. 1–3 They frequently have altered circadian rhythms that contribute to fragmented sleep and waking patterns.4 Persons with AD have significantly higher average frequency ratings on number of nightly awakenings, nightly sleep duration, time taken to fall asleep, time awake during night, waking up too early, and restless sleep.5 These sleep disturbance symptoms can also result in sleep disturbance symptoms for caregivers with up to 66% of caregivers of persons with AD reporting sleep disturbance symptoms such as longer sleep onset latency, longer wake after sleep onset, frequent awakenings and poor sleep quality.6,7,8

In addition to experiencing sleep disturbance symptoms, caregivers also report high burden.6 One survey of 205 AD patients’ caregivers examined the frequency and severity of burden caused by seven sleep-related patient behaviors.9 Roughly one-third of respondents had a “high disturbance” score, indicating that patients’ sleep problems were a source of significant caregiver burden. However, Tractenberg and colleagues 10 found that some sleep behaviors rated as the most frequent or severe were not associated with the highest ratings of burden. For example, daytime napping received one of the highest frequency ratings but the lowest burden rating. These results suggest that the presence of sleep disturbance in patients with AD does not necessarily increase the burden of caregiving and that the level of burden can vary considerably based on the type of sleep abnormality.

Research has also shown that caregivers also report lower quality of life (QoL).11,12 Caregivers are at greater risk for mental and physical health problems including depression,6,13,14 and overall poor health compared to age-matched no-caregiver controls15 which can contribute to their assessment of a poor QoL. Moon and colleagues16 reported that that higher care-recipient activities of daily living (ADL) limitations were also associated with lower QoL.

To elucidate the role that caregiver-perceived care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms play in AD caregiving, we examined the relationships among caregiver reports of patients’ sleep disturbance symptoms and caregivers’ burden and QoL. The aims of the present investigation were thus to 1) determine the prevalence of symptoms of disturbed sleep in patients with AD, 2) identify the care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms that predict caregiver burden and QoL, and 3) determine how care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms compare to other caregiver characteristics, such as depressive symptoms and finances, and patient factors, such as functional status, when predicting QoL. We hypothesized that the caregiver-perceived sleep disturbance symptoms which involved caregiver awakening, i.e., nocturnal wandering, nocturnal awakening, and snoring, would predict caregiver burden; however, they would not be as important in predicting QoL when other caregiving factors are included in the model.

Methods

The study was a cross-sectional, secondary data analysis of data collected from caregivers of community-dwelling patients who met National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria for probable or possible AD.17 The survey was conducted during the semi-annual visit at the Penn Memory Center of the University of Pennsylvania’s Alzheimer Disease Center. Caregivers provided written informed consent prior to completing the surveys, and the study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Measures

In addition to demographics, caregivers completed questions about burden, QoL, physical and mental health status, depressive symptoms, care-recipients’ ability to perform basic activities of daily living (BADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and care-recipients’ sleep. The physician assessed care-recipients’ depression and cognitive impairment.

Demographics

Demographic information collected from the caregiver included the relationship with the care-recipient, education, employment status, and monthly household income.

Burden

Caregiver burden was assessed using the Screen for Caregiver Burden (SCB), a 25-item scale that measures level of caregiver distress from various patient behaviors.18 To calculate a burden score, the “no occurrence” and “occurrence, but no distress” response options were each assigned a score of 1, while the other response options retained their scoring (i.e., “occurrence with moderate distress” has a score of 3). The scores were then summed. Scores ranged from 25–100.18 The SCB has been found to be reliable with caregivers of persons with AD.19

Quality of life

QoL was assessed using a single item that asked caregivers to “Please rate your overall quality of life at present” and was followed by five Likert options ranging from “poor” to “excellent” (1 to 5, respectively).20

Physical and mental health status

Physical and mental health status were assessed using the Medical Outcomes Survey Short-Form: Physical and Mental Composite Score [SF-12 PCS; SF-12 MCS]. The SF-12 PCS provides an overall physical health rating (range: 0–100) with higher scores indicate greater perceived physical health. The SF-12 MCS provides an overall mental health rating (range: 0–100) with high SF-12 MCS scores indicating better overall emotional well-being.21,22 The SF-36 scale has been found to be reliable with older adults.23

Depressive symptoms

Caregiver depressive symptoms were measured using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D 10). 24 A single score was computed as a sum of the individual questions (possible range 0–24), with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptomatology and scores ≥7 indicating significant depressive symptomatology.24 The CES-D 10 has been found to be valid and reliable with older adults.25

Care recipient’s ability to perform basic activities of daily living (BADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)

Caregivers responded to one question each that asked if the care-recipients needed assistance with BADLs and IADLs (yes or no response).

Caregiver perception of care-recipients’ sleep

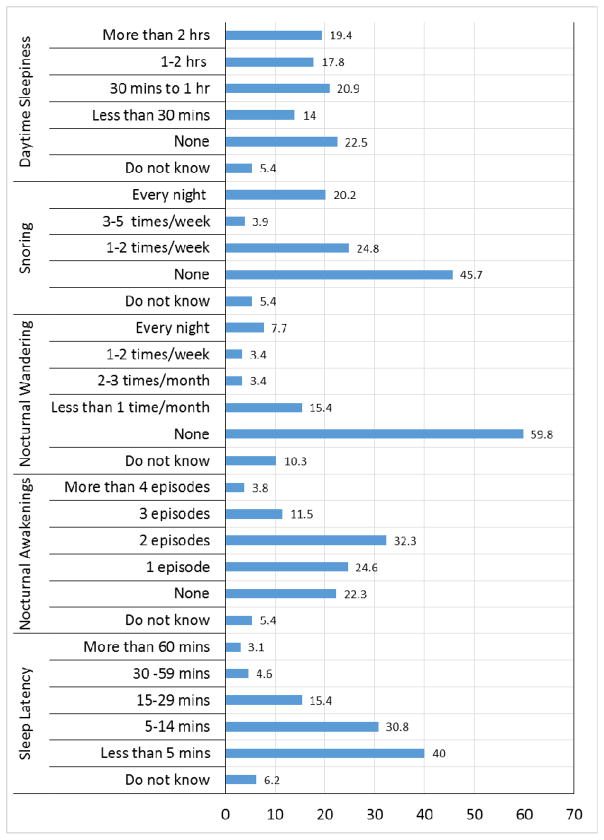

Caregivers rated several aspects of the care-recipients’ sleep over the past month: sleep latency (the amount of time taken to fall asleep), average number of nocturnal awakenings, frequency of nocturnal wandering, frequency of loud nocturnal snoring, and average duration of daytime naps. Each question was followed by five to six Likert-style response options (Figure 1). Care-recipients were considered to have symptoms of sleep disturbance if they were reported to have any of the following: a sleep latency greater than 30 minutes, three or more nocturnal awakenings per night, frequency of nocturnal wandering greater than once per month, frequency of loud snoring greater than twice per week, and/or spending greater than one hour asleep during the day. These thresholds were based on criteria commonly used in clinical trials of interventions for sleep disturbance as well as clinical judgment.26–28

Figure 1.

Prevalence of caregiver-perceived sleep complaints

Care-recipients’ depressive symptoms

The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)-short form, administered to the patient by the clinician, rated the patient’s depressive symptoms. 29 Higher scores (range of 0–15; scores >5 suggest depression) indicate more severe depression. The 15-item GDS has been found to be reliable and valid with older adults.30

Care-recipients’ cognitive status

Care-recipients’ cognitive status was assessed with the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), which has a range of scores from 0–30, with lower scores indicating more severe dementia.31 The MMSE has been found to be reliable and valid with older adults.32,33

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed to characterize sleep in the persons with AD. As part of this descriptive analysis, we examined the level of caregiver burden associated with specific sleep symptoms using univariate linear regression models. Individuals who responded “don’t know” to specific sleep questions were excluded from the analysis related to that question. To correct for multiple comparisons, a conservative Bonferroni correction was used. We then examined the effect of the sleep disturbance symptoms on caregiver QoL. Factors significantly associated with caregiver QoL at a p<0.10 were included in a multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis. All statistical analysis was done using SPSS v24.

Results

The initial study population consisted of 203 community-dwelling caregiver and care-recipient pairs. Data were not used if the family member responding as the caregiver was not the primary caregiver or did not live with the care recipient (n=73).34 The final sample used data from 130 caregiver/care-recipient dyads. Caregivers’ mean age was 65.8 (SD±11.3) years. The majority of the caregivers were female (60%), Caucasian (87.9%), and wives of the care-recipients (45.4%). The care-recipients’ mean age was 69.5(SD±8.3) years. Approximately half of them were female (49%) and the majority were Caucasian (86.2%). Table 1 presents the sample’s characteristics. The mean score for the MMSE was 17.8(SD±8.3). Of note, examination of the depressive symptoms for the caregivers and care-recipient samples indicated they were non-depressed on a whole; caregiver mean was 3.19(SD±1.71) and care-recipient mean was 2.6(SD±2.8). Only about 6% of caregivers and 3% of the care-recipients were depressed. Overall, the majority (81.4%) of caregivers reported that their QOL was good to excellent (i.e., greater than or equal to three).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | Patient | Caregiver |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 70.8 (SD=8.1; range=51 to 87) | 66.1 (SD=11.7; range=24.7 to 89.8) |

| Female | 50% | 61% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 87% | 86.5% |

| African-American | 13% | 12.5% |

| Mini-mental status exam score | 17.8 (SD=8.3; range=0 to 29) | |

| Depression severity | 2.3 (SD=2.7; range=0 to 13) (15-item Geriatric Depression Scale) | 1.9 (SD=2.2; range=0 to 9)(CES-D, 10 items) |

| Caregiver relationship | ||

| Wife | 45% | |

| Husband | 36% | |

| Daughter | 13% | |

| Son | 2% | |

| Other | 4% | |

| Yearly household income | ||

| less than $20,000 | 77.6% | |

| $20,000 – $39,999 | 20.4% | |

| $40,000 – $59,999 | 2.0% | |

CES-D- Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, SD-Standard Deviation

Figure 1 shows the frequency of the caregivers’ reports of the quality and quantity of the care-recipients’ sleep disturbance symptoms. Approximately eight percent reported that care-recipients took 30 or more minutes to fall asleep; 15.4% reported that care-recipients had two or more nocturnal awakenings; 14.5% reported that care-recipients wandered at least one time weekly during the night; almost a quarter (24%) had loud snoring more than two times weekly; and 37.2% reported that care-recipients had daytime sleepiness of more than an hour daily. Based on the criteria for defining sleep disturbance symptoms described above, 78(60%) care-recipients were reported to have at least one sleep disturbance symptom.

A series of univariate linear regressions were then performed with the outcome variable being caregiver burden. After a Bonferroni correction was applied (in which a critical alpha of .05/5=.01 was used), nocturnal awakenings, nocturnal wandering, snoring, and daytime sleepiness remained significant. Caregiver burden was significantly associated with the following specific sleep symptoms: nocturnal awakenings (F(1,103)=15.6, p<.001); nocturnal wandering (F(1,103)=15., p<.001), snoring (F(1,120)=9.9, p=.002), and daytime sleepiness more than one hour daily (F(1,120)=10.1, p<.001).

Univariate linear regressions were next used to examine the relationship between each sleep disturbance symptom and QoL as an outcome. After Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied, there were significant associations between caregiver QoL and any of the specific patient sleep disturbance symptoms.

Multivariate analyses were then performed to determine the relative importance of the care-recipients’ sleep disturbance symptoms on caregiver QoL when compared to other factors that may influence caregiver QoL. Univariate analyses were initially performed to determine which predictors should be included in multivariate models. A 0.10 significance level was used to determine entrance in multivariate models, which led to the inclusion of nocturnal awakenings, snoring, ability to perform IADLs and BADLs, caregiver level of education, financial status, caregiver physical and mental health, caregiver depressive symptoms, caregiver burden, care-recipient MMSE score, and care-recipient dementia severity rating scale. Using a stepwise selection method, the variables included in the final model (F(4,54=14.2, p<0.001, r2=0.51) were caregiver burden (F(1,57)=23.0, p<.001, r2=.29), physical health status (F(2,56)=14.7, p<0.001, r2=.34); mental health status (F(3,55=14.6, p<.001, r2=.44), and caregiver depression (F(4,54=14.2, p<0.001, r2=0.51). No sleep disturbance symptoms was statistically significant in this model. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Stepwise multiple regression model results for caregiver quality of life

| B | β | t | r | R2 | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | .536 | .287 | 22.928 | .000 | |||

| Burden | −.067 | −.536 | −4.788 | .000 | |||

| Model 2 | .586 | .344 | 14.655 | .000 | |||

| Burden | −.070 | −.559 | −5.140 | .000 | |||

| PCS | .040 | .239 | 2.200 | .032 | |||

| Model 3 | .666 | .414 | 14.642 | .000 | |||

| Burden | −.036 | −.287 | −2.157 | .035 | |||

| PCS | .057 | .336 | 3.179 | .002 | |||

| MCS | .043 | .435 | 3.153 | .003 | |||

| Model 4 | .512 | .476 | 14.187 | .000 | |||

| Burden | −.041 | −.327 | −2.588 | .012 | |||

| PCS | .060 | .358 | 3.573 | .001 | |||

| MCS | .072 | .735 | 4.324 | .000 | |||

| CES-D | .221 | .415 | 2.752 | .008 |

CES-D- Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, PCS- Physical Composite Score, MCS- Mental Composite Score

Discussion

The aim of the present investigation was to determine the prevalence of sleep disturbance symptoms in persons with AD, identify the care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms that predict caregiver burden and QoL, and determine how care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms compare to other caregiver and patient characteristics when predicting QoL. We found that sleep disturbance symptoms were common in this sample of persons with AD and predicted caregiver burden and QoL. Specifically, nocturnal wandering, nocturnal awakening, snoring, and daytime sleepiness predicted caregiver burden. However, no sleep disturbance symptoms predicted QoL after the inclusion of additional caregiver and patient characteristics such as burden, physical and mental health status, and caregiver depressive symptoms.

Of the sample, 60% had sleep disturbance symptoms sufficiently severe to be considered abnormal. The prevalence rate in this care-recipient sample was high but this rate is has been seen in other studies in this population.2,35,36 The most common sleep problems were daytime sleepiness and snoring. Considering that snoring and daytime sleepiness are symptoms of sleep apnea, untreated sleep apnea is likely an important contributory factor, which is not surprising since previous studies have shown that the prevalence of sleep apnea is higher in older adults, especially those with dementia.37,38 Preliminary evidence suggests that the sleep fragmentation and repeated hypoxemia of untreated sleep apnea can exacerbate dementia and, in extreme cases, produce dementia-like symptoms in otherwise non-demented individuals.39 Recent trials have shown reduced daytime sleepiness and possibly improved cognitive function in AD patients who receive continuous positive airway pressure treatment for their sleep apnea.40,41 Ironically, daytime sleepiness and napping as symptoms may be less likely than other sleep symptoms to raise a caregiver’s concern because providing care may be easier for sleepy individuals.42

A strong relationship existed between care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms and caregivers’ burden. Disturbed sleep symptoms of note were more frequent nocturnal awakenings, nocturnal wandering, and snoring. It is not surprising that the strongest effects were seen for nocturnal awakenings, nocturnal wandering, and snoring since these behaviors are likely to have the greatest impact on the sleep of caregivers.43 These results are consistent with those of previous studies that also found that wakefulness at night, although among the less commonly reported symptoms, was associated with the greatest burden.6,9,10

The relationship between sleep disturbance symptoms and caregiver burden likely follows a threshold model in which caregivers are able to manage or adapt to the poor sleep until a ‘tipping point’ is reached. Research has shown that sleep problems are often a key factor in the decision to admit an elder to a nursing home.44 Beyond this level of severity, providing care becomes difficult, in part because of the caregiver’s own cumulative sleep loss. Individual caregivers vary in the degree of sleep disturbance they can manage, and this threshold is likely affected by other factors such as AD severity and depression. Ultimately, sleep disturbance symptoms are components which predict caregiver burden and can have a significant negative impact on caregiver burden over time.

With the inclusion of caregiver and patient characteristics in the model, care-recipient sleep disturbance symptoms did not predict QoL. Caregiver burden and their mental and physical health status were the significant predictors of caregiver QoL. While the mean depressive score and the percentage of caregivers with significant depressive symptoms were low, depressive symptoms were still a predictor of QoL. This suggests that emotional appraisals of caregiving influence how caregivers evaluate their QoL.45 In addition, poor physical and emotional health can increase caregivers’ burden.45,46 With the presence of these factors, care-recipients’ sleep disturbance symptoms are not then significant predictors of QoL.

Several important limitations of the current study should be considered. As with many studies of the impact of sleep, self-report was used as the source of data about sleep, and the potential inaccuracies of self-report data are well known.47 We did not include a specific question to assess whether the caregiver and care-recipient shared the same bedroom or bed for sleep. When these questionnaires are completed by caregivers or sleep partners, as was the case in the AD cohort in this study, there may be some loss of validity in certain items since the caregiver may sleep through symptomatic episodes. This parallels the clinical situation with memory impaired subjects when we rely on caregivers for symptomatic report.5 To confirm and extend the results of the current study, future studies should measure both subjective and objective care-recipient sleep and examine their associations with caregiver burden and QoL.

The study is cross-sectional in nature, and thus causality cannot be assessed. In addition, cross-sectional studies are subject to survivorship effects that may diminish potential associations. For the regression analyses, we used stepwise instead of hierarchical regression. While stepwise analyses tend to inflate R-squared values and are particularly problematic when predictor variables are highly correlated, there is insufficient a priori or theoretical research to support ordering the predictor variables in any particular way. Also, quality of life, and BADL/IADL assistance were assessed with single items. Future studies should use validated measures to assess QoL and BADL/IADL limitations.

Lastly, the study sample was drawn from the patient population at a university hospital memory center, which may have ramifications for study generalizability. However, this center is a principal site for AD research at the University of Pennsylvania, including NIH-funded epidemiological research, and has several outreach mechanisms to ensure adequate representation of a diverse population. Most patients in the study had mild to moderate levels of cognitive impairment from AD, and thus these findings do not necessarily apply to caregivers of patients with severe cognitive impairment from AD; however, the majority of patients that are community-dwelling have mild to moderate AD.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that sleep disturbance symptoms are relatively common in individuals with dementia and predict caregiver burden. Healthcare providers should also consistently assess for sleep disturbance symptoms in both the individuals with dementia and their caregivers. Interventions aimed at identifying and treating those with sleep disturbance may ease the burden of caregiving in this population. In the case of sleep apnea, treatment may slow the rate of cognitive decline. Furthermore, it has been suggested that high caregiver burden can result in dysfunctional caregiver behaviors that could negatively impact the course of the patient’s dementia.18 If such a reciprocal interaction exists, treating disturbed sleep could have important public health impact by improving the lives of both the caregiver and the individual with dementia.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Penn Memory Center for their assistance with this study.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [NIA K23 AG01021, NIA P30-AG-010124, T32-HL07713].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McCurry SM, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003;5(3):261–272. doi: 10.1007/s11940-003-0017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rongve A, Boeve BF, Aarsland D. Frequency and correlates of caregiver-reported sleep disturbances in a sample of persons with early dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(3):480–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cagnin A, Fragiacomo F, Camporese G, et al. Sleep-Wake Profile in Dementia with Lewy Bodies, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Normal Aging. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2017;55(4):1529–1536. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musiek ES, Xiong DD, Holtzman DM. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer Disease. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2015;47(3):e148. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tractenberg RE, Singer CM, Kaye JA. Symptoms of sleep disturbance in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and normal elderly. Journal of sleep research. 2005;14(2):177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creese J, Bedard M, Brazil K, Chambers L. Sleep disturbances in spousal caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(1):149–161. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, Vitiello MV. Sleep disturbances in caregivers of persons with dementia: Contributing factors and treatment implications. Sleep medicine reviews. 2007 Apr;11(2):143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKibbin CL, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale J, et al. Sleep in spousal caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep. 2005;28(10):1245–1250. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, et al. Characteristics of sleep disturbance in community-dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;12(2):53–59. doi: 10.1177/089198879901200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tractenberg RE, Singer CM, Cummings JL, Thal LJ. The Sleep Disorders Inventory: an instrument for studies of sleep disturbance in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Sleep Res. 2003;12(4):331–337. doi: 10.1046/j.0962-1105.2003.00374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell CM, Araki SS, Neumann PJ. The association between caregiver burden and caregiver health-related quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(3):129–136. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scholzel-Dorenbos CJ, Draskovic I, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Quality of life and burden of spouses of Alzheimer disease patients. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009 Apr-Jun;23(2):171–177. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e318190a260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kochar J, Fredman L, Stone KL, Cauley JA. Sleep problems in elderly women caregivers depend on the level of depressive symptoms: results of the Caregiver--Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Dec;55(12):2003–2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Aoust RF, Brewster G, Rowe MA. Depression in informal caregivers of persons with dementia. International journal of older people nursing. 2015;10(1):14–26. doi: 10.1111/opn.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martire LM, Hall M. Dementia caregiving: recent research on negative health effects and the efficacy of caregiver interventions. CNS Spectr. 2000;7(11):791–796. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900024305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon H, Townsend AL, Whitlatch CJ, Dilworth-Anderson P. Quality of Life for Dementia Caregiving Dyads: Effects of Incongruent Perceptions of Everyday Care and Values. The Gerontologist. 2016 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vitaliano PP, Young HM, Russo J, Romano J, Magana-Amato A. Does expressed emotion in spouses predict subsequent problems among care recipients with Alzheimer’s disease? J Gerontol. 1993;48(4):P202–209. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitaliano PP, Russo J, Young HM, Becker J, Maiuro RD. The Screen for Caregiver Burden1. The Gerontologist. 1991;31(1):76–83. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James BD, Xie SX, Karlawish JH. How do patients with Alzheimer disease rate their overall quality of life? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(6):484–490. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Kolinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandeck B. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Resnick B, Nahm ES. Reliability and validity testing of the revised 12-item Short-Form Health Survey in older adults. Journal of nursing measurement. 2001;9(2):151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irwin M, Artin K, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: Criterion validity of the 10-item center for epidemiological studies depression scale (ces-d) Archives of internal medicine. 1999;159(15):1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, et al. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep. 2004;27(8):1567–1596. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lan TY, Lan TH, Wen CP, Lin YH, Chuang YL. Nighttime sleep, Chinese afternoon nap, and mortality in the elderly. Sleep. 2007 Sep 1;30(9):1105–1110. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zammit G, Erman M, Wang-Weigand S, Sainati S, Zhang J, Roth T. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of ramelteon in subjects with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5):495–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyunt MS, Fones C, Niti M, Ng TP. Criterion-based validity and reliability of the Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) in a large validation sample of community-living Asian older adults. Aging & mental health. 2009 May;13(3):376–382. doi: 10.1080/13607860902861027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hébert R. Community screening for dementia: The Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50(4):377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Connor DW, Pollitt PA, Hyde JB, et al. The reliability and validity of the mini-mental state in a British community survey. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1989;23(1):87–96. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(89)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raccichini A, Castellani S, Civerchia P, Fioravanti P, Scarpino O. The caregiver’s burden of Alzheimer patients: differences between live-in and non-live-in. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009;24(5):377–383. doi: 10.1177/1533317509340025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bliwise D. Sleep in dementing illness. In: Oldham JM, Riba MB, editors. American Psychiatric Press Review of Psychiatry. Vol. 13. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. pp. 757–776. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCurry SM, Song Y, Martin JL. Sleep in caregivers: what we know and what we need to learn. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2015;28(6):497–503. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ancoli-Israel S, Gehrman P, Kripke DF, et al. Long-term follow-up of sleep disordered breathing in older adults. Sleep Med. 2001;2(6):511–516. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gehrman PR, Martin JL, Shochat T, Nolan S, Corey-Bloom J, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep-disordered breathing and agitation in institutionalized adults with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(4):426–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bliwise DL. Sleep in normal aging and dementia. Sleep. 1993;16(1):40–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chong MS, Ayalon L, Marler M, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure reduces subjective daytime sleepiness in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease with sleep disordered breathing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):777–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ancoli-Israel S, Palmer BW, Cooke JR, et al. Cognitive effects of treating obstructive sleep apnea in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2076–2081. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JH, Bliwise DL, Ansari FP, et al. Daytime sleepiness and functional impairment in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(7):620–626. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180381521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowe MA, Kelly A, Horne C, et al. Reducing Dangerous Nighttime Events in Persons with Dementia Using a Nighttime Monitoring System. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2009;5(5):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pollak CP, Perlick D, Linsner JP, Wenston J, Hsieh F. Sleep problems in the community elderly as predictors of death and nursing home placement. J Community Health. 1990;15(2):123–135. doi: 10.1007/BF01321316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srivastava G, Tripathi RK, Tiwari SC, Singh B, Tripathi SM. Caregiver Burden and Quality of Life of Key Caregivers of Patients with Dementia. Indian journal of psychological medicine. 2016;38(2):133–136. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.178779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreakou MI, Papadopoulos AA, Panagiotakos DB, Niakas D. Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life for Caregivers of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2016;2016:9213968. doi: 10.1155/2016/9213968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185(4157):1124–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]