Abstract

Ischaemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is the leading cause of injury seen in the liver following transplantation. IRI also causes injury following liver surgery and haemodynamic shock. The first cells within the liver to be injured by IRI are the liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC). Recent evidence suggests that LSEC co-ordinate and regulates the livers response to a variety of injuries. It is becoming increasingly apparent that the cyto-protective cellular process of autophagy is a key regulator of IRI. In particular LSEC autophagy may be an essential gatekeeper to the development of IRI. The recent availability of liver perfusion devices has allowed for the therapeutic targeting of autophagy to reduce IRI. In particular normothermic machine liver perfusion (NMP-L) allow the delivery of pharmacological agents to donor livers whilst maintaining physiological temperature and hepatic flow rates. In this review we summarise the current understanding of endothelial autophagy and how this may be manipulated during NMP-L to reduce liver IRI.

Keywords: Autophagy, Liver transplant, Ischaemia-reperfusion injury, Normothermic machine liver perfusion

Core tip: Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells autophagy regulates liver ischaemia reperfusion injury and this process can be targeted for therapeutic benefit using normothermic machine liver perfusion.

INTRODUCTION

The term autophagy is derived from the Greek meaning “eating of self” and the precise cellular role of autophagy has been controversial[1]. However research over the past decade has demonstrated that the evolutionarily conserved process of autophagy is primarily a cell survival mechanism allowing cells and tissues to maintain homeostasis during periods of stress such as starvation and ischaemia[2]. Specifically autophagy eliminates damaged organelles, long-lived proteins or intracellular pathogens through the co-ordinated engulfment of the targeted cargo in a double membrane cytoplasmic structure known as an autophagosome[3,4]. Autophagosomes then fuse with lysosomes to form autophagolysosomes that degrade the engulfed cargo allowing their reuse and thus potentially negating periods of cellular stress[2,4-6]. Hence unsurprisingly autophagy is involved in number of cellular processes such as metabolism, protein synthesis and cellular transportation[4,7]. Dysregulated or uncoordinated autophagy is linked to cell injury and a number of disease processes such as neurodegenerative diseases and cancer[2,4,6,7].

Three distinct types of autophagy have been characterised. The mostly widely studied is macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy hereafter) and is the primary focus of this review[4,5,8]. Micro-autophagy is characterized by the invagination of the target by the lysosomal membrane itself[5,9]. Chaperone-mediated autophagy targets proteins with the KFERQ motif to the lysosome via interaction with lysosomal-associated membrane protein (LAMP)[9,10]. More recently distinct macroautophagy signalling pathways have been characterised that are activated to specifically eliminate portions of the cell and/or cytoplasm leading to the characterisation of mitophagy (mitochondria), ERphagy (endoplasmic reticulum), xenophagy (microorganisms), lipophagy (lipids) and ribophagy (ribosomes). It is becoming increasingly apparent that specific forms of autophagy are important in the development and pathophysiology of different disease processes. The precise regulation of each type of autophagy is beyond the scope of this review but the reader is referred to recent excellent reviews on the subject[2,4,6,7].

The therapeutic targeting of autophagy has gathered momentum since the publication of the first clinical trials using autophagy inhibitors in treatment of cancers[11-13]. For instance autophagy inhibitors (e.g., hydroxychloroquine) were used in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and in those patients with increased levels of the autophagy marker LC3 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells there was an improvement in disease free and patient survival[11]. However in other trials using hydroxychloroquine in patients with glioblastoma the optimal therapeutic dose was not found due to the marked side effects with the investigators concluding that drugs with less toxicity should be awaited[12]. Although these studies have provided the impetus to manipulate autophagy it still remains to be established whether autophagy should be activated or inhibited to derive therapeutic benefit in many disease processes. Moreover many groups working on the therapeutic manipulation of autophagy are now suggesting that the targeting of autophagy during pathophysiological processes needs to tissue and possibly even cell specific[14].

The use of autophagy as a target in treating liver diseases have been the focus of intense recent research[15]. Indeed the manipulation of autophagy may be useful in treating many liver diseases. For instance induction of autophagy/lipophagy may reduce steatosis in fatty liver disease[16] and inhibiting autophagy in hepatobiliary cancers may promote cancer cell death[11,17]. The manipulation of the autophagy signalling pathway also holds significant promise in attempting to reduce the liver ischaemia-reperfusion injury (IRI). IRI is an antigen independent pro-inflammatory process that mediates liver injury following transplantation, liver surgery and haemorrhagic shock[18]. The injury occurs in two distinct phases. In the ischaemia phase blood flow to the liver is interrupted leading to tissue hypoxia and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). During the reperfusion phase although blood flow to the liver is restored there is a concomitant increase in pro-inflammatory mediators, ROS and inflammatory cells that amplifies the liver injury[18]. It is well established that IRI targets and injuries the liver parenchymal cells such as hepatocytes and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC)[19]. However early IRI is characterised by LSEC injury and dysfunction[19]. Indeed recent studies demonstrate the key role of LSEC in co-ordinating the livers response to injury whilst also mediating the recovery from liver injury[20]. Thus the targeting of autophagy in the LSEC during IRI is an attractive method with which to reduce liver IRI.

The emerging technology of normothermic machine perfusion of the liver (NMP-L) provides an exciting modality with which to target autophagy in LSEC whilst simultaneously allowing an assessment of liver function[21]. There are different NMP-L devices available allowing either selective hepatic artery perfusion or dual hepatic perfusion of donor livers. Using primarily blood based perfusion fluids, oxygen is delivered to donor livers whilst maintaining a normal temperature (37 °C). NMP-L is typically performed for 6 h and the sequential sampling of perfusates and liver tissue allows a dynamic assessment of liver function. One of the many potential benefits of NMP-L is the reduction in the liver IRI. Therefore, the manipulation of autophagy in LSEC during NMP-L is an attractive therapeutic target with which to improve donor liver organ function prior to transplantation.

AUTOPHAGY SIGNALLING PATHWAY

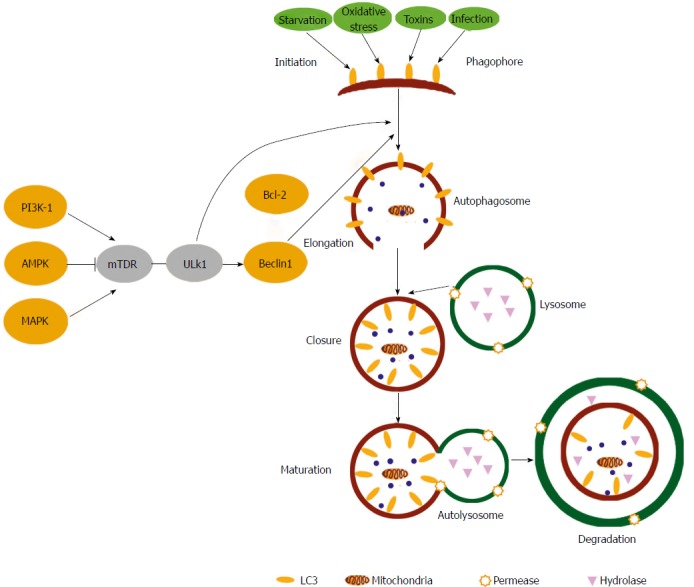

The autophagy signalling pathway is regulated by specific and dedicated cellular machinery. These proteins were first isolated in yeast two-hybrid screens and are now known as the Autophagy-related proteins (ATGs). To date 30 ATGs have been characterised that are essential for autophagy induction. Recent reviews by Stork et al[21] provide an in-depth review of the pathway whilst a brief overview is given here. In general the autophagy signalling pathway can be divided into distinct phases including the initiation, elongation, autophagosome formation, fusion and autophagolysosomal formation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Autophagy signalling pathways. Upstream autophagy activation is regulated by the integration of signalling from a number of pathways including AMPK, PI-3K and the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. Phagophore initiation is directly regulated by the serine/threonine protein kinases ULK1 that forms a complex with Beclin 1. Upon initiation, cytoplasmic constituents are enclosed in a double membraned isolation structure known as an autophagosome that is elongated mainly through the action of two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems. Autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes to form autophagolysosomes, where breakdown of the vesicle contents/cargo takes place along with the autophagosome inner membrane. Autophagy can be activated by many stimuli including starvation, toxins, oxidative stress and infections. (Taken from Shan NN et al Targeting autophagy as a potential therapeutic approach for immune thrombocytopenia therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016; 100: 11-15. DOI: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.01.011).

The formation of autophagosomes commences upon omegasomes and is known as the initiation phase[22]. This process is regulated by the ATG proteins unc-51 like autophagy activation kinase (ULK1) and WIPI1-4/ATG18[22,23]. Starvation is a classical activator of autophagy and in nutrient rich conditions the activation of autophagy is inhibited by Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR)[24]. However when autophagy is activated, the inhibitory effect of mTOR is lost allowing for the activation of ULK1 kinase complex during the initiation phase[9]. In addition autophagy can also be initiated by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)[25] (Figure 1). Subsequently there is recruitment of class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K), Vps34 and Beclin-1/ATG6 to the developing autophagosome[5,9]. ULK1 is then able to activate the PI3-K complex leading to the activation of Beclin-1 and the later phases of autophagy. This pathway details the canonical autophagy signalling pathway but recent evidence suggests that autophagy can be activated by Beclin-1 independent mechanisms/non-canonical pathways too[9,26].

The elongation phase of autophagy involves two separate ATG conjugation systems. Firstly ATG12 conjugates ATG5 via ATG7/ATG10. The ATG12-ATG5 complex is then able to interact with ATG16 resulting in the formation of the ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L complex[5,27]. The second conjugation system involves LC3-I/ATG8 that is cleaved by ATG4 in a process requiring ATG7 and ATG3. This culminates in the formation of LC3-II[5,28]. Both these conjugation systems are integral to autophagosome membrane expansion[4,7,9]. At the point at which appropriate membrane expansion has been reached there is closure of double layered membrane that is regulated by amongst other proteins the docking protein p62 which is located on the outer membrane of the autophagosome and is responsible for docking with the lysosome via a dynein-dependent mechanism[5]. Thereafter, lysosomal acid hydrolases degrade the engulfed content/cargo and lysosomal efflux permeases release the final products to the cytosol for anabolic processes (Figure 1).

AUTOPHAGY AND ENDOTHELIAL CELLS

Regulation of autophagy activation in endothelial cells

Much of our understanding of the role of autophagy in endothelial cells, such as LSEC, has come from the study of endothelial cell biology in cardiovascular disease. Recent studies have demonstrated how autophagy dysfunction in endothelial cells contributes to the pathogenesis of arthrosclerosis by regulating angiogenesis, haemostasis and nitric oxide production[9].

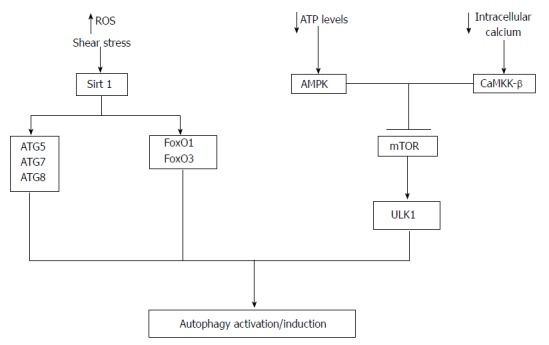

In endothelial cells upstream activation of the autophagy is regulated by the integration of signalling from the AMPK and mTOR-ULK1 pathways[9] (Figure 1). AMPK can detect decreases in cellular ATP levels and activate autophagy primarily to provide substrates for energy used for essential cellular processes[9,29] (Figure 2). Specifically AMPK phosphorylates the Tuberous Sclerosis 2 (TSC2) protein that inhibits mTOR and activates autophagy in an analogous mechanism to that seen during starvation[9,29-33]. In HeLa cells starvation increases intracellular calcium levels and can activate AMPK through Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-β (CaMKK-β) that then subsequently activates autophagy[9,34,35]. In endothelial cells CaMKK-β mediated AMPK activation inhibits mTOR leading to ULK1 upregulation and autophagy activation[34]. Thus in endothelial cells the activation of autophagy is a dynamic interplay between AMPK, intracellular calcium, mTOR and ULK-1.

Figure 2.

Autophagy activation in endothelial cells. A number of mechanisms potentially regulate autophagy activation in endothelial cells. A decrease in cellular ATP or reduction in growth factors availability leads to the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Once activated AMPK can inhibit mTOR leading to the activation of ULK1 and hence autophagy activation. In addition decreases in intracellular calcium can activate CaMKK-β leading to mTOR inhibition and autophagy activation. Moreover, Sirt1 can activate autophagy via deacetylation of ATG5, ATG7, ATG8 and increased transcription of FoxO1 and FoxO3 that then regulate the expression ATGs via deacetylation of Akt. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and shear stress are important regulators of Sirt1 activity.

The deacylation protein Sirt1 has attracted recent attention as an important regulator of autophagy activation. Specifically Sirt1 can deacetylate ATG5, ATG7, and ATG8[9,36] whilst activating the transcription factors Forkhead box O (FoxO) FoxO1 and FoxO3. Both FoxO1 and FoxO3 can regulate the expression of ATGs via deacetylation of Akt[9,35,37-39]. Indeed during liver IRI ROS can regulate the activation of Sirt1, which may have important implications for endothelial cell autophagy during NMP-L[9,40-43]. Specifically perfusion fluid used during NMP-L induces tangential force across the endothelium causing shear stress that is associated with autophagy activation via the Sirt1-FoxO pathway[43]. Low shear stress is associated with reduced levels of autophagy suggesting an important relationship between shear stress and autophagy[44]. Therefore autophagy activation in endothelial cell can be regulated by multiple signalling pathways and at present is remains to be established which of these pathways is important during NMP-L.

Effects of autophagy on endothelial cell function

Autophagy activation has recently been demonstrated to have a number of important effects upon endothelial cell function. Following endothelial injury exposure of the sub-intimal layer promotes glycoproteins, expressed on platelets, to bind to subendothelial von Willebrand Factors (vWF) leading to the formation of a platelet thrombus and production of thromboxane A2, serotonin and adenosine diphosphate[34]. Recent studies demonstrate that vWF is found in close proximity to autophagosomes in endothelial cells[35]. The inhibition of autophagy impairs the secretion of vWF from endothelial cells suggesting that endothelial cell autophagy may have an anti-thrombotic function[45].

In endothelial cells, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) regulates nitric oxide (NO) production that in turn regulates vascular tone, platelet aggregation and leukocyte adhesion[46]. Indeed this may be a central function of endothelial cells during liver IRI and a potential protective mechanism induced within the liver by NMP-L. Furthermore eNOS can regulate autophagy induction[47,48]. The exact mechanisms involved in eNOS/NO-autophagy axis are not yet understood although impaired autophagy does result in reduced eNOS function reduced NO production[49].

As eluded to earlier blood flow within the liver generates shear stress across the endothelium that is associated with induction of eNOS and NO production[50]. This is in turn associated with a reduction in oxidative stress and inflammation in endothelial cells. Disturbed shear stress generated by non-laminar flow is associated with endothelial dysfunction that can be implicated in disease processes such as arthrosclerosis[50]. Hence low shear induces autophagy dysfunction[48] which is associated with insufficient autophagy activation in endothelial cells and thus endothelial dysfunction[43]. NMP-L may aid endothelial cell autophagy by ensuring laminar flow within the hepatic vasculature thereby prompting autophagy leading to increased eNOS transcription and NO production. In summary, physiologic shear stress is an essential mechanism for the maintenance of endothelial cells function and is in part mediated by autophagy activation[47].

Autophagy activation is also associated with angiogenesis in endothelial cells particularly within ischaemic microenvironments[51]. The relationship between redox signalling and autophagy is complex and out of the scope of this review although it has been recently reviewed[42]. Autophagy regulation of angiogenesis appears to be dependent upon the activation of the Akt signalling pathway in endothelial cells although the precise mechanism remains to be determined[9,51,52].

Therapeutic targeting of autophagy in endothelial cells

The evolving understanding of the autophagy signalling pathway has lead to the targeting of the pathway for potential therapeutic benefit in many clinical scenarios. However what is becoming evident from these studies is that for the successful therapeutic targeting of autophagy the timing of the intervention, the part of the autophagy pathway targeted, the cell type targeted and whether autophagy should be inhibited or activated are all critical factors. The targeting of autophagy within endothelial cells remains a nascent field with few studies investigating this area.

Epigallocatechin gallate, found in green tea, can induce the specific form of autophagy known as lipophagy in endothelial cells. Lipophagy causes the specific elimination of lipid droplets. In artheroscelosis the degradation of lipid droplets in vascular endothelial cells can potentially modulate the disease process by allowing endothelial cells to resist the effects of lipotoxicity[35,53]. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) exposed to oxidative stress, vitamin D dependent autophagy activation prevents cell death by activating Beclin1 that prevents mitochondrial depolarisation and caspase activation[54]. Pterostilbene can activate AMPK to stimulate autophagy in HUVEC promoting the elimination of excess lipids and thus reducing apoptosis[53] whilst other groups have suggest that Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) may regulate the activation of autophagy in this scenario[55]. Furthermore the autophagy activator rapamycin can increase the viability of HUVEC during starvation[56]. These limited studies do suggest that selective activation of autophagy in cells of endothelial lineage promotes cell survival.

Very few studies have addressed the role of autophagy in endothelial cells in vivo. Torisu et al[45] reported, using a Cre-lox conditional ATG7 endothelial knockdown mice, that inhibition of autophagy leads a reduction in the secretion of vWF suggesting that autophagy may have a role in preventing thrombosis. However the role of endothelial cell autophagy in vivo need much more investigation.

THERAPEUTIC MANIPULATION OF ENDOTHELIAL CELL AUTOPHAGY DURING NMP-L

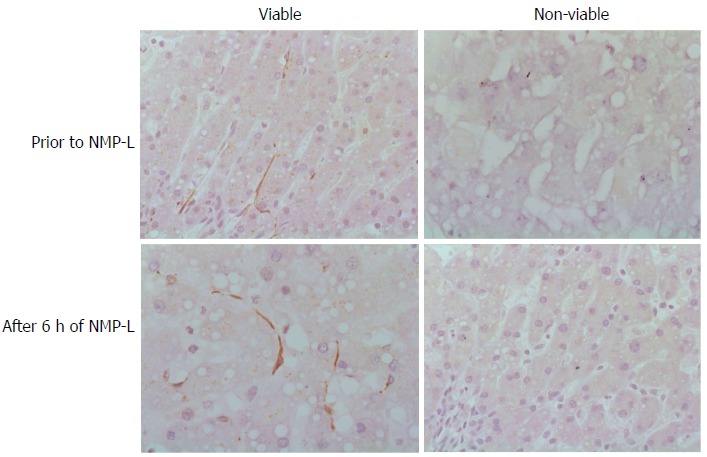

NMP-L is a novel technique that can be employed to assess and recondition donor livers prior to transplantation. One of the potential benefits of NMP-L is the potential reduction in liver IRI especially when compared to traditional static cold storage[57,58]. Recent studies have established haemodynamic and biochemical parameters that allow donor livers to be classified as viable and non-viable where viable denotes a liver that can be transplanted following NMP-L. Indeed donor livers represent conditions were autophagy is expected to be activated; relative tissue ischaemia and reduced availability of nutrients. Recent data from our laboratory has shown that donor livers that demonstrate these viability criteria shows increased levels of autophagy within hepatic sinusoids as assessed by immunohistochemical analysis of the specific autophagy marker LC3B (Figure 3). This suggests a relationship between autophagy induction and liver viability although further work is needed to fully establish this relationship.

Figure 3.

Autophagy and liver viability following normothermic machine liver perfusion. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed for the autophagy protein LC3B in liver tissue prior to normothermic machine liver perfusion (NMP-L) and after 6 h of NMP-L. Livers deemed viable after NMP-L demonstrated LC3B immunostaining in the hepatic sinusoids prior to commencing NMP-L and at the end of perfusion. Donor livers not fulfilling viability criteria demonstrated no LC3B Immunostaining.

As discussed above targeting of autophagy needs to be considered in terms of the timing of intervention, the cell type targeted and the part of the autophagy pathway targeted. During NMP-L there are two forms of intervention that could modulate autophagy in endothelial cells; mechanical or pharmacological.

Livers exposed to NMP-L are associated with increased cellular ATP levels in comparison to cold static stored livers. For instance in a porcine model of donation after cardiac death (DCD) livers exposed to 1 h warm ischaemia, followed by 2 h of cold ischaemia and then 4 h of NMP-L increased cellular ATP levels by 80% in comparison with livers maintained in cold static storage for 2 h[59]. Higher ATP levels within liver grafts prior to liver transplantation are associated with better patient outcomes in some series[60,61]. Although it must be remembered that these studies have assessed global liver ATP levels and not specifically LSEC ATP levels. Additionally, NMP-L is associated with preservation of liver architecture and integrity of the mitochondria[59]. The regulation of mitochondrial function and number is regulated in large part by the specific autophagy process termed mitophagy[62]. The regulation of mitophagy during NMP-L and liver IRI is now being actively investigated as a potential method to reduce liver injury following transplantation[62]. The manipulation of mitophagy in LSEC is emerging as a method to reduce liver injury. However despite this it remains to be established whether LSEC autophagy contributes to increased ATP levels during NMP-L and whether autophagy, through promoting survival of LSEC, improves the survival of neighbouring liver parenchymal cells.

NMP-L may also regulate autophagy activation through calcium signalling. During NMP-L the perfusion fluid is supplemented with calcium to maintain physiological extracellular levels of the ion ensuring that the electrochemical gradient of calcium is maintained across cell membranes[58]. Low intracellular levels of calcium are reported to induce CaMMk-β activation followed by mTOR inhibition and therefore ULK1/autophagy activation[34]. Physiological calcium levels during NMP-L potentially promote normal autophagy activity within LSEC and other liver cells ensuring homeostasis is maintained.

The mechanical manipulation of autophagy during NMP-L is dependent upon shear stress. NMP-L has the advantage of providing an adjustable vascular/laminar flow rate to livers. In turn these flow rate provides a near physiological shear stress known to promote autophagy induction[43]. Activated autophagy in endothelial cells is fundamental for eNOS transcription, NO production and maintenance of vascular tone maintenance[47]. Increased NO may also reduce platelet aggregation and leukocyte adhesion in endothelial cells thus reducing IRI and hepatic microcirculatory disturbance[63].

Pharmacological modulation of autophagy during NMP-L may also allow the targeting of endothelial cells dysfunction in donor liver grafts prior to transplantation. Extended criteria liver donors (e.g., DCD grafts and steatotic grafts) tend to be associated with lower cellular ATP content and increased ROS production increasing their susceptibility to IRI[57,59]. Pharmacological agents promoting activation of autophagy during NMP-L may promote elimination of damaged organelles and toxins prior to graft implantation. In particular aiding mitophagy function may be crucial to maintaining LSEC function during NMP-L and thus aiding the survival of other liver cells. As described above, many drugs are already known to regulate autophagy activation and the use of these drugs in experimental NMP-L perfusion offers an important method to evaluate these interventions. This manipulation of autophagy in LSEC using NMP-L is an exciting area of interest for research groups working on liver IRI particularly as this technology will become more widespread in addition to the development of new autophagy modulating drugs.

CONCLUSION

In summary, autophagy is a complex metabolic process that is essential for the cell survival; it promotes clearance of harmful substances and provides energy to the cell during cellular stress. The role of autophagy in endothelial cells and its manipulation using NMP-L offers significant promise in reducing liver IRI thereby improving the quality of donor liver organs used for transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper presents independent research that was supported by the NIHR Liver Biomedical Research Unit at the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors would like to thank the Hepato-pancreatico-biliary/liver transplant surgery team at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom for the access to human liver tissue. Ricky Bhogal was funded by research grant from The Wellcome Trust (DDDP.RCHX14183), St John’s Ambulance Travelling Fellowship in Transplantation and Academy of Medical Sciences (DKAA.RCZV18746).

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

P-Reviewer: Yan LN S-Editor: Qi Y L-Editor: E-Editor:

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Peer-review started: May 5, 2017

First decision: June 7, 2017

Article in press: July 12, 2017

P- Reviewer: Yan LN S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Yuri L Boteon, The Liver Unit, University Hospitals of Birmingham, Mindelsohn Way, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; The Centre for Liver Research, Centre for Liver Research, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute for Biomedical Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom.

Richard Laing, The Liver Unit, University Hospitals of Birmingham, Mindelsohn Way, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; The Centre for Liver Research, Centre for Liver Research, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute for Biomedical Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom.

Hynek Mergental, The Liver Unit, University Hospitals of Birmingham, Mindelsohn Way, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; The Centre for Liver Research, Centre for Liver Research, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute for Biomedical Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom.

Gary M Reynolds, The Centre for Liver Research, Centre for Liver Research, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute for Biomedical Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom.

Darius F Mirza, The Liver Unit, University Hospitals of Birmingham, Mindelsohn Way, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; The Centre for Liver Research, Centre for Liver Research, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute for Biomedical Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom.

Simon C Afford, The Centre for Liver Research, Centre for Liver Research, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute for Biomedical Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom.

Ricky H Bhogal, The Liver Unit, University Hospitals of Birmingham, Mindelsohn Way, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom ricky.bhogal@uhb.nhs.uk; The Centre for Liver Research, Centre for Liver Research, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute for Biomedical Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Swart C, Du Toit A, Loos B. Autophagy and the invisible line between life and death. Eur J Cell Biol. 2016;95:598–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010;221:3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman SJ, Zhang Y, Jin S. Autophagic degradation of mitochondria in white adipose tissue differentiation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1971–1978. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhogal RH, Weston CJ, Curbishley SM, Adams DH, Afford SC. Autophagy: a cyto-protective mechanism which prevents primary human hepatocyte apoptosis during oxidative stress. Autophagy. 2012;8:545–558. doi: 10.4161/auto.19012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jing K, Lim K. Why is autophagy important in human diseases? Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:69–72. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.2.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroemer G, Mariño G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2010;40:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klionsky DJ. Autophagy. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R282–R283. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang F. Autophagy in vascular endothelial cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;43:1021–1028. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saftig P, Beertsen W, Eskelinen EL. LAMP-2: a control step for phagosome and autophagosome maturation. Autophagy. 2008;4:510–512. doi: 10.4161/auto.5724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boone BA, Bahary N, Zureikat AH, Moser AJ, Normolle DP, Wu WC, Singhi AD, Bao P, Bartlett DL, Liotta LA, et al. Safety and Biologic Response of Pre-operative Autophagy Inhibition in Combination with Gemcitabine in Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4402–4410. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4566-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenfeld MR, Ye X, Supko JG, Desideri S, Grossman SA, Brem S, Mikkelson T, Wang D, Chang YC, Hu J, et al. A phase I/II trial of hydroxychloroquine in conjunction with radiation therapy and concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Autophagy. 2014;10:1359–1368. doi: 10.4161/auto.28984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Hu Q, Shen HM. Pharmacological inhibitors of autophagy as novel cancer therapeutic agents. Pharmacol Res. 2016;105:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Towers CG, Thorburn A. Therapeutic Targeting of Autophagy. EBioMedicine. 2016;14:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Netea-Maier RT, Plantinga TS, van de Veerdonk FL, Smit JW, Netea MG. Modulation of inflammation by autophagy: Consequences for human disease. Autophagy. 2016;12:245–260. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1071759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cingolani F, Czaja MJ. Regulation and Functions of Autophagic Lipolysis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27:696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nitta T, Sato Y, Ren XS, Harada K, Sasaki M, Hirano S, Nakanuma Y. Autophagy may promote carcinoma cell invasion and correlate with poor prognosis in cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4913–4921. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannistrà M, Ruggiero M, Zullo A, Gallelli G, Serafini S, Maria M, Naso A, Grande R, Serra R, Nardo B. Hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury: A systematic review of literature and the role of current drugs and biomarkers. Int J Surg. 2016;33 Suppl 1:S57–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyashita T, Nakanuma S, Ahmed AK, Makino I, Hayashi H, Oyama K, Nakagawara H, Tajima H, Takamura H, Ninomiya I, et al. Ischemia reperfusion-facilitated sinusoidal endothelial cell injury in liver transplantation and the resulting impact of extravasated platelet aggregation. Eur Surg. 2016;48:92–98. doi: 10.1007/s10353-015-0363-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLeve LD. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and liver regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1861–1866. doi: 10.1172/JCI66025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravikumar R, Jassem W, Mergental H, Heaton N, Mirza D, Perera MT, Quaglia A, Holroyd D, Vogel T, Coussios CC, et al. Liver Transplantation After Ex Vivo Normothermic Machine Preservation: A Phase 1 (First-in-Man) Clinical Trial. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1779–1787. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wesselborg S, Stork B. Autophagy signal transduction by ATG proteins: from hierarchies to networks. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4721–4757. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2034-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamb CA, Yoshimori T, Tooze SA. The autophagosome: origins unknown, biogenesis complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:759–774. doi: 10.1038/nrm3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruf S, Heberle AM, Langelaar-Makkinje M, Gelino S, Wilkinson D, Gerbeth C, Schwarz JJ, Holzwarth B, Warscheid B, Meisinger C, et al. PLK1 (polo like kinase 1) inhibits MTOR complex 1 and promotes autophagy. Autophagy. 2017;13:486–505. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1263781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song YM, Lee YH, Kim JW, Ham DS, Kang ES, Cha BS, Lee HC, Lee BW. Metformin alleviates hepatosteatosis by restoring SIRT1-mediated autophagy induction via an AMP-activated protein kinase-independent pathway. Autophagy. 2015;11:46–59. doi: 10.4161/15548627.2014.984271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spencer B, Potkar R, Trejo M, Rockenstein E, Patrick C, Gindi R, Adame A, Wyss-Coray T, Masliah E. Beclin 1 gene transfer activates autophagy and ameliorates the neurodegenerative pathology in alpha-synuclein models of Parkinson’s and Lewy body diseases. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13578–13588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4390-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizushima N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Tanaka Y, Ishii T, George MD, Klionsky DJ, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature. 1998;395:395–398. doi: 10.1038/26506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, Satomi Y, Shimonishi Y, Ishihara N, Mizushima N, Tanida I, Kominami E, Ohsumi M, et al. A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature. 2000;408:488–492. doi: 10.1038/35044114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altman BJ, Rathmell JC. Metabolic stress in autophagy and cell death pathways. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a008763. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cantó C, Auwerx J. AMP-activated protein kinase and its downstream transcriptional pathways. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:3407–3423. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0454-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Høyer-Hansen M, Jäättelä M. AMP-activated protein kinase: a universal regulator of autophagy? Autophagy. 2007;3:381–383. doi: 10.4161/auto.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor R, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghislat G, Patron M, Rizzuto R, Knecht E. Withdrawal of essential amino acids increases autophagy by a pathway involving Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-β (CaMKK-β) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38625–38636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HS, Montana V, Jang HJ, Parpura V, Kim JA. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) stimulates autophagy in vascular endothelial cells: a potential role for reducing lipid accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22693–22705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.477505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee IH, Cao L, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, Liu J, Bruns NE, Tsokos M, Alt FW, Finkel T. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci US. 2008;105:3374–3379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712145105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sengupta A, Molkentin JD, Yutzey KE. FoxO transcription factors promote autophagy in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28319–28331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang H, Tindall DJ. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2479–2487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qiang L, Banks AS, Accili D. Uncoupling of acetylation from phosphorylation regulates FoxO1 function independent of its subcellular localization. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27396–27401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.140228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen W, Tian C, Chen H, Yang Y, Zhu D, Gao P, Liu J. Oxidative stress mediates chemerin-induced autophagy in endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;55:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng M, Wei X, Wu Z, Li W, Li B, Fei Y, He Y, Chen J, Wang P, Liu X. Reactive oxygen species contribute to simulated ischemia/reperfusion-induced autophagic cell death in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1017–1023. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Navarro-Yepes J, Burns M, Anandhan A, Khalimonchuk O, del Razo LM, Quintanilla-Vega B, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI, Franco R. Oxidative stress, redox signaling, and autophagy: cell death versus survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:66–85. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J, Bi X, Chen T, Zhang Q, Wang SX, Chiu JJ, Liu GS, Zhang Y, Bu P, Jiang F. Shear stress regulates endothelial cell autophagy via redox regulation and Sirt1 expression. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1827. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li R, Jen N, Wu L, Lee J, Fang K, Quigley K, Lee K, Wang S, Zhou B, Vergnes L, et al. Disturbed Flow Induces Autophagy, but Impairs Autophagic Flux to Perturb Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;23:1207–1219. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torisu T, Torisu K, Lee IH, Liu J, Malide D, Combs CA, Wu XS, Rovira II, Fergusson MM, Weigert R, et al. Autophagy regulates endothelial cell processing, maturation and secretion of von Willebrand factor. Nat Med. 2013;19:1281–1287. doi: 10.1038/nm.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shu X, Keller TC 4th, Begandt D, Butcher JT, Biwer L, Keller AS, Columbus L, Isakson BE. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the microcirculation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4561–4575. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo F, Li X, Peng J, Tang Y, Yang Q, Liu L, Wang Z, Jiang Z, Xiao M, Ni C, et al. Autophagy regulates vascular endothelial cell eNOS and ET-1 expression induced by laminar shear stress in an ex vivo perfused system. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:1978–1988. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Q, Li X, Li R, Peng J, Wang Z, Jiang Z, Tang X, Peng Z, Wang Y, Wei D. Low Shear Stress Inhibited Endothelial Cell Autophagy Through TET2 Downregulation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016;44:2218–2227. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L, Wang X, Miao Y, Chen Z, Qiang P, Cui L, Jing H, Guo Y. Magnetic ferroferric oxide nanoparticles induce vascular endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammation by disturbing autophagy. J Hazard Mater. 2016;304:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davies PF. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:16–26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Du J, Teng RJ, Guan T, Eis A, Kaul S, Konduri GG, Shi Y. Role of autophagy in angiogenesis in aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C383–C391. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00164.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang BH, Liu LZ. AKT signaling in regulating angiogenesis. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:19–26. doi: 10.2174/156800908783497122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang L, Cui L, Zhou G, Jing H, Guo Y, Sun W. Pterostilbene, a natural small-molecular compound, promotes cytoprotective macroautophagy in vascular endothelial cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:903–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uberti F, Lattuada D, Morsanuto V, Nava U, Bolis G, Vacca G, Squarzanti DF, Cisari C, Molinari C. Vitamin D protects human endothelial cells from oxidative stress through the autophagic and survival pathways. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1367–1374. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie Y, You SJ, Zhang YL, Han Q, Cao YJ, Xu XS, Yang YP, Li J, Liu CF. Protective role of autophagy in AGE-induced early injury of human vascular endothelial cells. Mol Med Rep. 2011;4:459–464. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Urbanek T, Kuczmik W, Basta-Kaim A, Gabryel B. Rapamycin induces of protective autophagy in vascular endothelial cells exposed to oxygen-glucose deprivation. Brain Res. 2014;1553:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Imber CJ, St Peter SD, Lopez de Cenarruzabeitia I, Pigott D, James T, Taylor R, McGuire J, Hughes D, Butler A, Rees M, et al. Advantages of normothermic perfusion over cold storage in liver preservation. Transplantation. 2002;73:701–709. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200203150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.op den Dries S, Karimian N, Sutton ME, Westerkamp AC, Nijsten MW, Gouw AS, Wiersema-Buist J, Lisman T, Leuvenink HG, Porte RJ. Ex vivo normothermic machine perfusion and viability testing of discarded human donor livers. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1327–1335. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu H, Berendsen T, Kim K, Soto-Gutiérrez A, Bertheium F, Yarmush ML, Hertl M. Excorporeal normothermic machine perfusion resuscitates pig DCD livers with extended warm ischemia. J Surg Res. 2012;173:e83–e88. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sumimoto K, Inagaki K, Yamada K, Kawasaki T, Dohi K. Reliable indices for the determination of viability of grafted liver immediately after orthotopic transplantation. Bile flow rate and cellular adenosine triphosphate level. Transplantation. 1988;46:506–509. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamiike W, Burdelski M, Steinhoff G, Ringe B, Lauchart W, Pichlmayr R. Adenine nucleotide metabolism and its relation to organ viability in human liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1988;45:138–143. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198801000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Go KL, Lee S, Zendejas I, Behrns KE, Kim JS. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Autophagy in Hepatic Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:183469. doi: 10.1155/2015/183469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rockey DC. Endothelial dysfunction in advanced liver disease. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:6–16. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]