Abstract

AIM

To investigate the impact of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) treatment on allergic colitis (AC) and gut microbiota (GM).

METHODS

We selected a total of 19 AC infants, who suffered from severe diarrhea/hematochezia, did not relieve completely after routine therapy or cannot adhere to the therapy, and were free from organ congenital malformations and other contraindications for FMT. Qualified donor-derived stools were collected and injected to the AC infants via a rectal tube. Clinical outcomes and follow-up observations were noted. Stools were collected from ten AC infants before and after FMT, and GM composition was assessed for infants and donors using 16S rDNA sequencing analysis.

RESULTS

After FMT treatment, AC symptoms in 17 infants were relieved within 2 d, and no relapse was observed in the next 15 mo. Clinical improvement was also detected in the other two AC infants who were lost to follow-up. During follow-up, one AC infant suffered from mild eczema and recovered shortly after hormone therapy. Based on the 16S rDNA analysis in ten AC infants, most of them (n = 6) had greater GM diversity after FMT. As a result, Proteobacteria decreased (n = 6) and Firmicutes increased (n = 10) in post-FMT AC infants. Moreover, Firmicutes accounted for the greatest proportion of GM in the patients. At the genus level, Bacteroides (n = 6), Escherichia (n = 8), and Lactobacillus (n = 4) were enriched in some AC infants after FMT treatment, but the relative abundances of Clostridium (n = 5), Veillonella (n = 7), Streptococcus (n = 6), and Klebsiella (n = 8) decreased dramatically.

CONCLUSION

FMT is a safe and effective method for treating pediatric patients with AC and restoring GM balance.

Keywords: Pediatric, Infantile allergic colitis, Fecal microbiota transplantation, Gut microbiota, Immune reaction

Core tip: This retrospective study explored the therapeutic effects and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) treatment in 19 allergic colitis (AC) infants who were younger than 1 year old. After FMT treatment, AC symptoms were relieved in the patients rapidly, and no patient relapsed within 15 mo. With gut microbiota (GM) analysis, six of ten patients exhibited higher microbial diversity after FMT treatment. Moreover, decreased Proteobacteria and increased Firmicutes supplied the hints of GM re-establishment in the patients after FMT treatment. Therefore, this work showed the curative effects of FMT in AC infants and its possible mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

Allergic colitis (AC) is a common infantile rectal bleeding disorder which is caused by severe allergic reactions within the digestive system[1,2]. AC is normally identified in infants younger than one year of age and its representative clinical features are hematochezia and diarrhea[3]. Bloody purulent stools, abdominal pain, and vomiting are also used to diagnose AC[3]. Various factors such as food allergens, aberrant immune system, and imbalanced gut microbiota (GM) are thought to contribute to AC[4-6].

Conventional therapies for AC are reducing exposure to suspicious allergens and applying hypoallergenic milk powder[7]. Baldassarre et al[8] used probiotics to treat AC infants and found that Lactobacillus GG may relieve symptoms of AC by altering GM composition[8]. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) can change gut micro-ecology more robustly in comparison to food or probiotics. Several reports suggested that FMT was therapeutically efficacious for treating diseases associated with GM dysbiosis, such as Clostridium difficile infection (CDI)[9,10], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[11,12], and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)[13,14]. However, to our knowledge, FMT has not been used to treat AC infants.

Thus, we assessed 19 AC infants with severe hematochezia and/or diarrhea, who had not acquired complete remission after 2 wk of routine therapy or because the guardians cannot adhere to the routine therapy thoroughly. Our intention was to confirm the safety and efficacy of FMT in AC treatment, and detect the sustained GM changes after FMT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (TJ-C20140712). All subjects and donors gave signed informed consent. Principles of patients care and all experimental procedures followed the guidelines established by the Institutional Review Board of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Patient selection

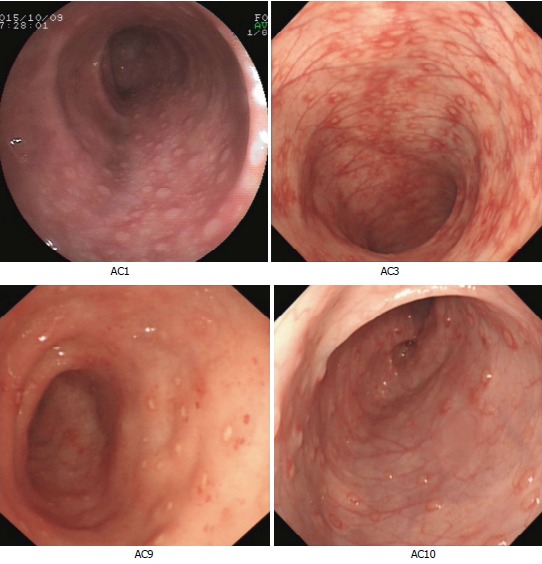

AC was diagnosed based on the following clinical symptoms: (1) rectal bleeding with/without mucus and diarrhea; (2) exclusion of infectious colitis, anal fissure, lymphoid nodular hyperplasia, and uncommon conditions such as necrotizing enterocolitis, Hirschsprung’s enterocolitis, IBD[15], and IBS[16]; (3) clinical remission after milk exclusion and recurrence after milk re-challenge[3,17]; and (4) histological examination indicated that the intestinal mucosa exhibited chronic inflammation with eosinophils infiltration and colonic lesions (Supplementary File 1). Pediatric AC patients meeting the following criteria were selected as FMT candidates: (1) the patients had no complete remission after routine therapy, the patients cannot adhere to the therapy thoroughly, or their parents had strong intention to receive the treatment of FMT; (2) free from contraindications for FMT, such as intestinal obstructions, perforations, and bleeding, or severe immunodeficiency diseases; and (3) colonoscopic inspection indicated no mucosal congestion, edema, multiple spot-like erosion, or lymphoid granular nodes (four cases included in Figure 1). As a result, 19 AC patients were enrolled in the study between September 2015 and December 2015 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Colonoscopic inspection of four allergic colitis patients prior to fecal microbiota transplantation. Colonoscopic images of patients (AC1, AC3, AC9, and AC10) were obtained prior to FMT. AC: Allergic colitis; FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation.

Table 1.

Clinical information for 19 allergic colitis infants

| ID | Gender | Age (mo) | Symptom(s) | Duration of disease (mo) | Treatment(s) before FMT | Donor source | FMT times | Symptom remission after first FMT (d) | Stool frequency before and after FMT (times/d) | Follow-up (mo) | Availability of gut microbiota data |

| AC1 | Female | 7 | Diarrhea, hematochezia sometimes; anemia; hypohepatia | > 3 | Applying amino acid formula and probiotics (C. butyricum) | Mother | 2 | 1 | 3-4, 1 | 19 | Yes |

| AC2 | Male | 10 | Hematochezia | > 0.5 | Applying amino acid formula and probiotics (Bifidobacteria) | Healthy infants aged 10 mo old | 2 | 1 | 2-3, 1 | 18 | Yes |

| AC3 | Female | 11 | Hematochezia | > 3 | Applying amino acid formula and probiotics (S. boulardii) | Healthy infants aged 8 mo old | 3 | 1 | 5-6, 2 | 19 | Yes |

| AC4 | Male | 9 | Hematochezia | > 3 | Applying amino acid formula and probiotics (S. boulardii) | Mother's cousin sister | 3 | 1 | 6-7, 1-2 | 18 | Yes |

| AC5 | Male | 5 | Diarrhea and hematochezia sometimes | > 3 | Applying amino acid formula | Healthy infants aged 8 mo old | 3 | 1 | 3-4, 2 | 19 | Yes |

| AC6 | Male | 5 | Hematochezia | > 3 | Applying amino acid formula and probiotics (C. butyricum) | Mother | 1 | 2 | 5-6, 1 | 18 | Yes |

| AC7 | Male | 4 | Hematochezia and cough sometimes | > 2 | Applying amino acid formula and nebulization | Mother | 2 | 2 | 4-7, 1 | 15 | Yes |

| AC8 | Female | 3 | Diarrhea and mucoid feces sometimes | > 2 | Applying amino acid formula | Mother | 2 | 1 | 3-4, 1-2 | 19 | Yes |

| AC9 | Male | 11 | Interval hematochezia | > 6 | Appling amino acid formula and probiotics (S. boulardii) | Mother | 2 | 1 | 3-4, 2 | 23 | Yes |

| AC10 | Female | 3 | Hematochezia | > 1.5 | Applying amino acid formula | Healthy infants aged 10 mo old | 4 | 2 | 5-6, 1 | 21 | Yes |

| AC11 | Male | 7 | Diarrhea | > 2 | Applying amino acid formula, probiotics (Bifidobacteria), Smecta and Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS) | Healthy infants aged 10 mo old | 5 | 1 | 5-6, 1 | 23 | No |

| AC12 | Female | 10 | Diarrhea and hematochezia sometimes | > 1 | Applying amino acid formula and probiotics (Bifidobacteria) | Mother | 3 | 1 | 5-6, 1-2 | 22 | No |

| AC13 | Male | 5 | Hematochezia and diahhrea sometimes | > 3 | Applying amino acid formula | Mother | 1 | 1 | 3-4, 1 | 15 | No |

| AC14 | Female | 5 | Hematochezia and then peptone shaped feces | > 1 | Applying amino acid formula and probiotics () | Mother | 1 | 1 | 7-8, 2 | 15 | No |

| AC15 | Male | 7 | Diarrhea | > 2 | Applying amino acid formula, ORS, and probiotics (C. butyricum) | Mother | 5 | 1 | 5-6, 1 | 21 | No |

| AC16 | Female | 5 | Interval hematochezia | > 2 | Appling amino acid formula | Healthy infants aged 8 mo old | 2 | 1 | 4-5, 1 | 21 | No |

| AC17 | Male | 7 | Diarrhea and hematochezia sometimes | > 3 | Applying amino acid formula, probiotics (Bifidobacteria and C. butyricum) | Healthy infants aged 11 mo old | 1 | 2 | 3-4, 1-2 | 0.5 | No |

| AC18 | Female | 8 | Diarrhea and cough sometimes | > 4 | Applying amino acid formula and nebulization | Healthy infants aged 8 mo old | 2 | 1 | 3-4, 2 | 17 | No |

| AC19 | Male | 5 | Interval diarrhea | > 4 | Applying amino acid formula | Mother | 4 | 1 | 3-4, 1 | 0.3 | No |

AC: Allergic colitis; FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation.

Donor screening

Patients’ mothers were considered to be donors of the highest priority, followed by fathers and healthy peers. Adult donors were screened as follows[18-20]: (1) no infectious diseases history (e.g., tuberculosis and hepatopathy); (2) no metabolic diseases history (e.g., obesity and diabetes); (3) no gastrointestinal diseases (e.g., diarrhea, constipation, IBD, IBS, colorectal polyps, and gastrointestinal tumors); (4) no allergic diseases (e.g., food allergy, eczema, and allergic gastroenteritis); (5) no antibiotic exposure in the last 3 months; (6) no mental disorders or autoimmune diseases; and (7) no drug abuse history, amenorrhea (for mother donors), or psychological imbalance.

Candidate donors of the same age were selected with the following criteria[18-20]: (1) preferred relatives with breast milk fed and same gender; (2) no antibiotic treatment in the last 3 months; (3) no allergic disease (e.g., food allergy, eczema, and allergic gastroenteritis); (4) no gastrointestinal disease (e.g., diarrhea, constipation, IBD, IBS, colorectal polyps, and gastrointestinal tumors); (5) no metabolic disease history (e.g., obesity and diabetes); and (6) no infectious disease history (e.g., tuberculosis, hepatopathy, and measles), and normal health and development. Tests for serum biochemistry and stool were performed for donors to ensure subject safety (Table 2).

Table 2.

Laboratory testing on donors

| Blood testing |

| Blood transfusion examinations: Quantifications of hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B surface antibody, hepatitis B E antigen, hepatitis B E antibody, hepatitis B core IgM antibody, hepatitis C antibody, human immunodeficiency virus antibody, and treponema pallidum antibody. |

| TORCH examinations: Detections on toxoplasmosis IgG, toxoplasmosis IgM, rubella virus IgG, rubella virus IgM, cytomegalovirus IgG, cytomegalovirus IgM, herpes simplex virus 1/2 IgG, and herpes simplex virus 1/2 IgM. |

| Detection on parvovirus B19. |

| Epstein-Barr virus examinations: Detections on Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen IgA, Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen IgG, Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen IgM, Epstein-Barr virus early antigen IgG, and Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen IgG. |

| Blood type examination. |

| Lymphocyte subpopulation examination. |

| Food allergen examination (sIgE). |

| Hepatic and renal function examinations: Glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, glutamic oxalacetic transaminase, total protein, albumin, globulin, prealbumin, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, gamma glutamyltranspeptidase, total cholesterol , triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, apolipoprotein A1, apolipoprotein B, lactic dehydrogenase, calcium, corrected calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, urea, creatinine, trioxypurine, bicarbonate radical, total bile acid, 5-nucleotidase, α-L-fucosidase, cholinesterase, cystatin C, and lipase andamylopsin. |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis antibody examination (or the enzyme-linked immuno-spot assay test for tuberculosis). |

| Immune system examinations: Quantifications of immune globulin A, immune globulin G, immune globulin M, alexin C3, and alexin C4. |

| Detection on hepatitis A-IgM. |

| Qualifications of C-reaction protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. |

| Stool testing |

| Fecal routine examinations: Detections on fecal color, character, red blood cells, white blood cells, occult blood, parasite eggs, protozoon, fat ball, rotavirus antigen, and fungus. |

| Bacterial culture tests: Detections on Vibrio cholera, Salmonella, Shigella, Aeromonas, Plesiomonas, and pathogenic Escherichia coli. |

| Other testing |

| Chest X-ray. |

| Urea[C13] Capsule Breath Test. |

| Abdominal ultrasound scan. |

| Electrocardiographic examination. |

FMT procedure

The application of parenteral nutrition and probiotics was stopped as soon as FMT began in the patients. No bowel preparation (cleanout or antibiotic pretreatment) was used prior to FMT, but pre-FMT clinical tests were performed as described in Table 3. Donor stool, collected 2 h before FMT, was diluted and mixed with sterile saline (1 mg of stool was diluted with 3 mL of saline). Samples were filtered through sterile gauze and 30-50 mL fecal suspension was prepared for FMT. FMT was administered over 5-10 min via a rectal tube into the left colon. The rectal tube was removed 15 min after administration and the fecal suspension was retained in the recipients’ gut for 4-6 h. Multi-FMT was given for patients with severe symptoms (Table 1).

Table 3.

Laboratory testing of the patients before fecal microbiota transplantation

| Blood testing |

| Hepatic and renal function examinations: Glutamic-pyruvic transaminas, glutamic oxalacetic transaminase, total protein, albumin, globulin, prealbumin, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, gamma glutamyltranspeptidase, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, apolipoprotein A1, apolipoprotein B, lactic dehydrogenase, calcium, corrected calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, urea, creatinine, trioxypurine, bicarbonate radical, total bile acid, 5-nucleotidase, α-L-ducosidase, cholinesterase, cystatin C, lipase, and amylopsin. |

| Food allergen examination (sIgE). |

| Lymphocyte subpopulation examination. |

| Detection on hepatitis A-IgM. |

| Blood transfusion examinations: Quantifications of hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B surface antibody, hepatitis B E antigen, hepatitis B E antibody, hepatitis B core IgM antibody, hepatitis C antibody, human immunodeficiency virus antibody, and treponema pallidum antibody. |

| TORCH examinations: Detections on toxoplasmosis IgG, toxoplasmosis IgM, rubella virus IgG, rubella virus IgM, cytomegalovirus IgG, cytomegalovirus IgM, herpes simplex virus 1/2 IgG, and herpes simplex virus 1/2 IgM. |

| Detection on parvovirus B19. |

| Blood coagulation examinations: Detections on prothrombin time, prothrombin activity, international normalized ratio, fibrinogen, activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time, and D-dimer. |

| Blood type examination. |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis antibody examination (or the enzyme-linked immuno-spot assay test for tuberculosis). |

| Stool testing |

| Fecal routine examinations: Detections on fecal color, character, red blood cells, white blood cells, occult blood, parasite eggs, protozoon, fat ball, rotavirus antigen, and fungus. |

| Bacterial culture tests: Detections on Vibrio cholera, Salmonella, Shigella, Aeromonas, Plesiomonas, and pathogenic Escherichia coli. |

| Other testing |

| Enteroscopic examination. |

| Abdominal ultrasound scan (intestinal adhesion). |

| Electrocardiographic examination. |

Follow-up

Clinical symptoms, stool frequency, symptom remission time, and adverse events (e.g., abdominal pain, gastrointestinal infection, constipation, fever, and allergic disease) were recorded at the end of FMT (Table 1). Follow-up was conducted at ≥ 15 mo after FMT, except for two cases with 0.3 and 0.5 mo follow-up (AC17 and AC19), to evaluate FMT efficacy and safety (Table 1). The remission of AC was defined as the cease of rectal bleeding and decreased stool frequency (no more than two times/d) in the patients. The primary endpoint was the improved AC symptoms and sustained clinical remission at 12 mo. Secondary endpoint was the safety of FMT which was implied by the occurrence of adverse events.

Microbiota analysis and statistics

Fecal microbiota was analyzed for ten patients before FMT and during follow-ups. Donor feces were also assayed for GM. Microbial DNA was extracted using a PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and the hyper-variable V3-V4 region was amplified using 338F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) primers. Library construction and sequencing were conducted on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, United States). Data filtration and analysis were performed as a prior report with the RDP database as an annotation reference[21]. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare samples of one patient, which were collected at different time points, and a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare donor and patient samples. Graphs were produced with R package (version 3.2.3).

RESULTS

Recipient characteristics

FMT recipients were aged from 4 to 11 mo (11 boys and 8 girls) and had hematochezia or severe diarrhea. Disease duration of AC patients was 0.5-3 mo for 16 cases and 3-6 mo for three cases (Table 1). Formula was replaced with hypoallergenic milk powder in all patients’ dietary, and 11 of them were exposed to probiotics before FMT treatment (Table 1). The colonoscopic inspection of four AC infants was included in Figure 1.

FMT safety and efficacy

Infants experienced low-quality sleep and weight loss since the onset of AC, but no one was malnourished. They had significant clinical remission within 2 d after the first FMT treatment (Table 1). After FMT, hematochezia or diarrhea rapidly improved in AC patients, and decreased defecation frequency with improved stool consistency was also observed (Table 1). Within more than 15 mo of follow-up, the symptoms of AC had not relapsed except two patients who were lost to follow-up (AC17 and AC19). Only one patient suffered from eczema, which appeared 2 mo after FMT and was resolved with hormone therapy. Beyond this, no other adverse event was recorded during FMT or the follow-up.

FMT treatment associated microbiota changes

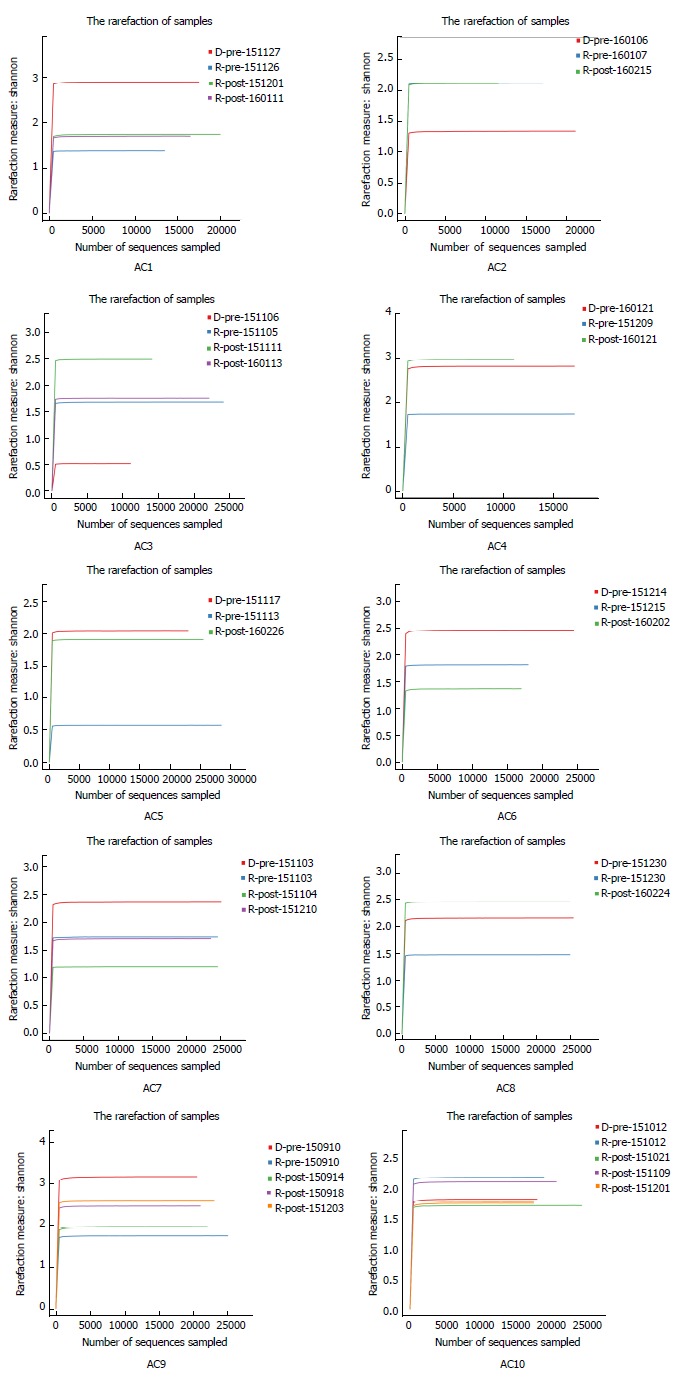

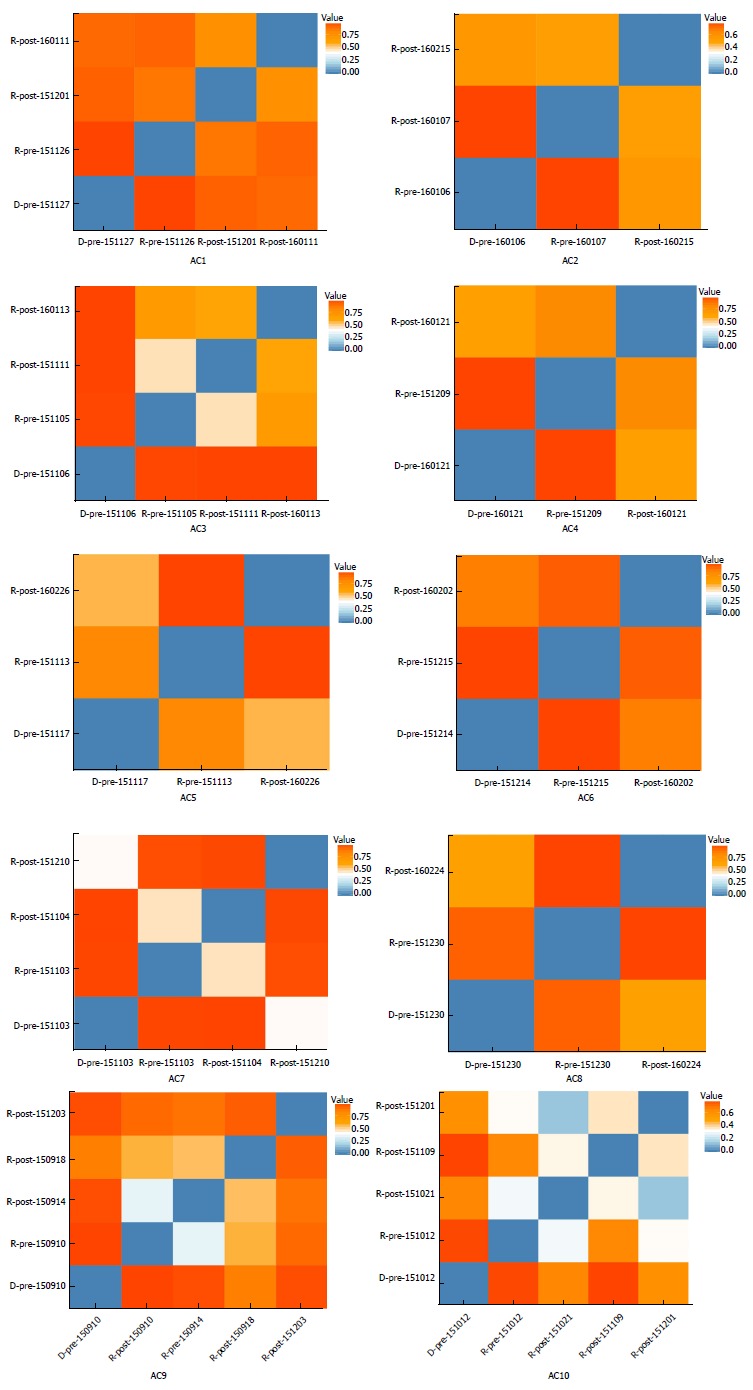

Figures 2 and 3 depict microbiota changes of ten patients before and after FMT compared to donors. Microbiota diversity increased dramatically in five patients while it decreased in three patients after FMT (Figure 2). When sampled 1 or 2 mon after FMT, microbiota of six patients was more similar to donors’ microflora by comparison with pre-FMT samples (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Shannon rarefaction curves of gut microbiota from ten allergic colitis infants and their donors. Each image represents one AC infant, and each curve represents one fecal sample from a patient or the corresponding donor. Sample ID has three parts: ‘R’ or ‘D’ indicates AC infants or donors, ’pre’ or ‘post’ represents the stools collected before or after FMT, and fecal collection date. Microbiota diversity in six patients (AC1, AC4, AC5, AC7, AC8, and AC9) increased after FMT treatment. AC: Allergic colitis; FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation.

Figure 3.

Microbiota similarity between allergic colitis infants and their donors. Values in red indicate low microbiota similarity between two samples. Blue represents high microbiota similarity. The microbiota compositions of patients (AC1, AC2, AC4, AC5, AC6, AC7, AC8, and AC10) were more similar to their donors’ composition after FMT treatment. One patient (AC9) had more and then less microbiota similarity and AC3 did not change in this regard. AC: Allergic colitis.

After FMT treatment, Firmicutes accounted for the greatest proportion of GM in the AC infants, followed by Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria. Proteobacteria decreased dramatically to < 10% for most patients except four patients (Supplementary File 2). Whilst, Firmicutes increased in all patients (Supplementary File 2).

The relative abundance of Escherichia significantly increased in eight AC infants (Supplementary File 3). Bacteroides increased in five AC infants including three who had no Bacteroides pre-FMT (Supplementary File 3). For four patients, Lactobacillus was enriched after FMT, but for three subjects, it was absent even after FMT. Possible pathogens including Clostridium and Klebsiella generally decreased after FMT. Clostridium and Klebsiella decreased in five and eight AC infants respectively (Supplementary File 3). The relative abundance of Streptococcus was lowered in six patients. Whilst, Veillonella was found decreased in seven patients and its relative abundance was no more than 8% after FMT. Bifidobacterium kept decreased in seven AC infants after FMT, and increased in two cases.

DISCUSSION

We chiefly considered the curative effects of FMT therapy in 19 AC infants and microbiota changes during treatment. Stools from both infant and adult donors suggested the same efficacy, and it was noted that all subjects had relieved symptoms of hematochezia and/or diarrhea in 2 d after the first FMT treatment. Due to the longer illness time or sever clinical symptoms, 15 patients experienced multi-FMT for the sustained clinical remission. And the multiple FMT in these patients gave us the idea that artificially modified microbiota for the specified patient might elevate the efficiency of FMT and attenuate transplantation times in the future. After being discharged from hospital, the patients were advised to take hypoallergenic milk powder instead of formula, and most patients had no relapse of colitis within more than 15 mo of follow-up. The recurrence of eczema in one infant might be caused by the inflammatory reactions which were triggered by discontinuous intake of hypoallergenic milk powder.

Fecal microbiota was analyzed in ten patients and their donors. We noted that the microbiota diversity increased in six patients after FMT. For three other subjects, GM diversity decreased after an initial increase while all the patients demonstrated clinical improvement. Individual-specific GM changes suggested the effect of donor’s GM complexity and patient’s gut micro-ecology imbalance. Khoruts et al[10] also suggested that bacteria can be eliminated due to nutrient competition, antimicrobial peptide suppression, and immune-mediated colonization resistance during GM re-establishment.

Proteobacteria, which contain opportunistic pathogens[22], decreased in six AC infants, and their relative abundance was less than 10% after FMT. In contrast, Firmicutes increased in all AC infants. Previous work implied that Firmicutes decreased in patients with Cohn’s disease[23], and the proportion of Firmicutes was negatively associated with gastrointestinal inflammation[24].

After FMT, the relative abundances of Bacteroides and Lactobacillus increased. Prior reports showed that species in Bacteroides could secrete polysaccharide A, which promoted the number of T regulatory (Treg) cells[25,26]. Interleukin (IL)-10 produced by Treg cells also eliminated inflammatory reactions and protected against infectious pathogens[25,26]. Lactobacillus can secrete lactic acid, increase the proportion of Treg cells, and relieve symptoms of AC[8,27]. Generally, the relative abundance of opportunistic pathogens decreased, including Veillonella, Streptococcus, Clostridium, and Klebsiella. Prior reports suggested that the combination of Veillonella and Streptococcus had been found in various GM systems and can augment IL-8, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) responses, which were associated with inflammatory reactions[28]. Clostridium can cause diarrhea via enterotoxin secretion, and Klebsiella was positively associated with macrophage migration-inhibitory factor (MIF) and affected host immunity[29]. However, GM imbalance and post-FMT improvement need more analysis to understand the mechanisms underlying AC improvements.

This study pioneered the application of FMT in AC treatment and provided important reference to understand microbiota changes before and after FMT. Although the results favor the application of FMT for AC treatment, it is still important to clarify whether AC symptoms can be improved in our future studies with larger sample size. Also, we will explore the microbiota changes at the gene or functional level before and after FMT, to further the understanding of GM imbalance and re-configuration during FMT treatment of infantile AC.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Allergic colitis (AC), which is characterized as hematochezia and severe diarrhea, is caused by an intense allergic reaction of the digestive system. Currently, first-line therapies for AC patients are reducing exposure to suspicious allergens and applying hypoallergenic milk powder. However, some pediatric patients could not relieve from AC symptoms completely with routine treatment, and long-term illness causes adverse impact on nutrition absorption and physical development in the children.

Research motivation

Previous studies indicated that gut microbiota (GM) was closely related with the digestive system, neural system, and immune system in human. Meanwhile, the positive effects of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) have been confirmed in various gastrointestinal diseases, including Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). However, FMT had not been applied to treat AC infants before. This research could provide important references for the treatment and research of infantile AC with FMT therapy.

Research objectives

The research aimed to detect the safety and efficiency of FMT treatment in AC, and compare GM composition before and after FMT treatment in the patients.

Research methods

The procedures of FMT, including selection of AC patients and donors, were conducted according to the guidelines established by the Institutional Review Board of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Wilcoxon tests were adopted in the research.

Research results

In this study, the safety and efficacy of FMT treatment were investigated in 19 AC infants with GM analysis. The results indicated that the AC symptoms, which included rectal bleeding, diarrhea and hematochezia, were relieved rapidly by FMT treatment. During the 15 mo follow-up, no relapse was recorded except that eczema happened in one patient. After FMT treatment, the elevation of microbial diversity was detected in six of ten patients. Meanwhile, the relative abundances of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes were decreased (6/10) and increased (10/10), respectively, in the AC infants.

Research conclusions

This study documents the positive effect of FMT treatment on infantile AC remission, suggesting the potential of FMT in gastrointestinal allergic diseases. Individual-specific GM re-configuration also extended our understanding of FMT efficacy and associated mechanisms.

Research perspectives

Despite the aspiring results of FMT in pediatric AC, verified improvements with larger cohorts and longer follow-up are necessary. In parallel, GM analysis should be performed before and after FMT, to unravel keystone microbial components in the specific disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the nurses who helped with sample collection at Tongji Hospital and the staff at WeHealthGene Institute who contributed to the project analysis.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Supported by National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project (Pediatric Digestive Disease), No. [2011]873.

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (IRB ID: TJ-C20140712).

Informed consent statement: All studied participants, or their legal guardians, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer-review started: September 5, 2017

First decision: September 27, 2017

Article in press: November 8, 2017

P- Reviewer: Daniel F, Iizuka M, Owczarek D S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Sheng-Xuan Liu, Department of Pediatrics, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Yin-Hu Li, Department of Microbial Research, WeHealthGene Institute, Shenzhen 518000, Guangdong Province, China.

Wen-Kui Dai, Department of Computer Science, College of Science and Engineering, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Xue-Song Li, Department of Pediatrics, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Chuang-Zhao Qiu, Department of Microbial Research, WeHealthGene Institute, Shenzhen 518000, Guangdong Province, China.

Meng-Ling Ruan, Department of Pediatrics, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Biao Zou, Department of Pediatrics, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Chen Dong, Department of Pediatrics, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Yan-Hong Liu, Department of Microbial Research, WeHealthGene Institute, Shenzhen 518000, Guangdong Province, China.

Jia-Yi He, Department of Pediatrics, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Zhi-Hua Huang, Department of Pediatrics, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Sai-Nan Shu, Department of Pediatrics, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China snshu@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ohtsuka Y. Food intolerance and mucosal inflammation. Pediatr Int. 2015;57:22–29. doi: 10.1111/ped.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feuille E, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome, Allergic Proctocolitis, and Enteropathy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:50. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xanthakos SA, Schwimmer JB, Melin-Aldana H, Rothenberg ME, Witte DP, Cohen MB. Prevalence and outcome of allergic colitis in healthy infants with rectal bleeding: a prospective cohort study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:16–22. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000161039.96200.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyburz A, Müller A. The Gastrointestinal Tract Microbiota and Allergic Diseases. Dig Dis. 2016;34:230–243. doi: 10.1159/000443357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheeler ML, Limon JJ, Bar AS, Leal CA, Gargus M, Tang J, Brown J, Funari VA, Wang HL, Crother TR, et al. Immunological Consequences of Intestinal Fungal Dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:865–873. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozen A, Gulcan EM, Ercan Saricoban H, Ozkan F, Cengizlier R. Food Protein-Induced Non-Immunoglobulin E-Mediated Allergic Colitis in Infants and Older Children: What Cytokines Are Involved? Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2015;168:61–68. doi: 10.1159/000441471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucarelli S, Di Nardo G, Lastrucci G, D’Alfonso Y, Marcheggiano A, Federici T, Frediani S, Frediani T, Cucchiara S. Allergic proctocolitis refractory to maternal hypoallergenic diet in exclusively breast-fed infants: a clinical observation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldassarre ME, Laforgia N, Fanelli M, Laneve A, Grosso R, Lifschitz C. Lactobacillus GG improves recovery in infants with blood in the stools and presumptive allergic colitis compared with extensively hydrolyzed formula alone. J Pediatr. 2010;156:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly CR, Ihunnah C, Fischer M, Khoruts A, Surawicz C, Afzali A, Aroniadis O, Barto A, Borody T, Giovanelli A, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection in immunocompromised patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ. Understanding the mechanisms of faecal microbiota transplantation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:508–516. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colman RJ, Rubin DT. Fecal microbiota transplantation as therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1569–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suskind DL, Singh N, Nielson H, Wahbeh G. Fecal microbial transplant via nasogastric tube for active pediatric ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:27–29. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holvoet T, Joossens M, Wang J, Boelens J, Verhasselt B, Laukens D, van Vlierberghe H, Hindryckx P, De Vos M, De Looze D, et al. Assessment of faecal microbial transfer in irritable bowel syndrome with severe bloating. Gut. 2017;66:980–982. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millan B, Laffin M, Madsen K. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Beyond Clostridium difficile. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2017;19:31. doi: 10.1007/s11908-017-0586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, Escher JC, Cucchiara S, de Ridder L, Kolho KL, Veres G, Russell RK, Paerregaard A, et al. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:795–806. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu MC, Tsai CL, Yang YJ, Yang SS, Wang LH, Lee CT, Jan RL, Wang JY. Allergic colitis in infants related to cow’s milk: clinical characteristics, pathologic changes, and immunologic findings. Pediatr Neonatol. 2013;54:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Tilg H, Rajilić-Stojanović M, Kump P, Satokari R, Sokol H, Arkkila P, Pintus C, Hart A, et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut. 2017;66:569–580. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourlioux P; workgroup of the French Academy of Pharmacy Faecal microbiota transplantation: Key points to consider. Ann Pharm Fr. 2015;73:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly CR, Kahn S, Kashyap P, Laine L, Rubin D, Atreja A, Moore T, Wu G. Update on Fecal Microbiota Transplantation 2015: Indications, Methodologies, Mechanisms, and Outlook. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:223–237. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fadrosh DW, Ma B, Gajer P, Sengamalay N, Ott S, Brotman RM, Ravel J. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome. 2014;2:6. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuentes S, Rossen NG, van der Spek MJ, Hartman JH, Huuskonen L, Korpela K, Salojärvi J, Aalvink S, de Vos WM, D’Haens GR, et al. Microbial shifts and signatures of long-term remission in ulcerative colitis after faecal microbiota transplantation. ISME J. 2017;11:1877–1889. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhagamhmad MH, Day AS, Lemberg DA, Leach ST. An overview of the bacterial contribution to Crohn disease pathogenesis. J Med Microbiol. 2016;65:1049–1059. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quévrain E, Maubert MA, Michon C, Chain F, Marquant R, Tailhades J, Miquel S, Carlier L, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Pigneur B, et al. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2016;65:415–425. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamada N, Seo SU, Chen GY, Núñez G. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:321–335. doi: 10.1038/nri3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramakrishna BS. Role of the gut microbiota in human nutrition and metabolism. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28 Suppl 4:9–17. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2016;535:75–84. doi: 10.1038/nature18848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van den Bogert B, Meijerink M, Zoetendal EG, Wells JM, Kleerebezem M. Immunomodulatory properties of Streptococcus and Veillonella isolates from the human small intestine microbiota. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lv LX, Fang DQ, Shi D, Chen DY, Yan R, Zhu YX, Chen YF, Shao L, Guo FF, Wu WR, et al. Alterations and correlations of the gut microbiome, metabolism and immunity in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:2272–2286. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]