Abstract

Flavor is an expression of olfactory and gustatory sensations experienced through a multitude of chemical processes triggered by molecules. Beyond their key role in defining taste and smell, flavor molecules also regulate metabolic processes with consequences to health. Such molecules present in natural sources have been an integral part of human history with limited success in attempts to create synthetic alternatives. Given their utility in various spheres of life such as food and fragrances, it is valuable to have a repository of flavor molecules, their natural sources, physicochemical properties, and sensory responses. FlavorDB (http://cosylab.iiitd.edu.in/flavordb) comprises of 25,595 flavor molecules representing an array of tastes and odors. Among these 2254 molecules are associated with 936 natural ingredients belonging to 34 categories. The dynamic, user-friendly interface of the resource facilitates exploration of flavor molecules for divergent applications: finding molecules matching a desired flavor or structure; exploring molecules of an ingredient; discovering novel food pairings; finding the molecular essence of food ingredients; associating chemical features with a flavor and more. Data-driven studies based on FlavorDB can pave the way for an improved understanding of flavor mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

Flavor is a complex, multi-sensory human experience with a rich evolutionary history (1). Molecules form the chemical basis of flavor expressed primarily via gustatory and olfactory mechanisms. The perception of flavor arises from interaction of flavor molecules with the biological machinery and could be perceived as an emergent property of a complex biochemical system. While some components of this puzzle have been unearthed, a holistic view of this phenomenon still eludes us (2–5). Taking a data-centric approach can provide a systems perspective of flavor sensation by offering ways to discern its key features.

Flavors derived from natural sources have shaped culinary habits throughout human history. Analogous to variations in regional languages, cultures have evolved variations in the way they cook. Traditional recipe compositions encode ingredient combinations that are not only palatable but appetizing. Heuristic associations between molecular properties and perception of flavors provide indications towards its chemical basis (1). For example, combinations of aliphatic esters play a major role in many fruit flavors. Ketones are known to impart metallic flavors in oxidized butter, and monoterpenoids provide the characteristic flavors of many herbs and spices. However, such knowledge remains largely unstructured and incomprehensive.

FlavorDB was created with the aim of integrating multidimensional aspects of flavor molecules and representing their molecular features, flavor profiles and details of natural source (Figure 1). FooDB, one of the efforts in similar direction, compiles molecules from food ingredients; although its focus is not on chemical basis of flavor or flavor pairing (http://foodb.ca). Flavornet is another resource, which provides a list of flavor molecules and their odor profiles, but does not furnish information of their natural sources (6). Other attempts in this direction have focused on compilation of data specific to aspects of flavors: tastes such as bitter (BitterDB) and sweet (SuperSweet), and volatile compounds of scents (SuperScent) (7–9). Certain others have targeted nutritional factors (NutriChem), polyphenols (Phenol-Explorer) and the medicinal value of food (10–13).

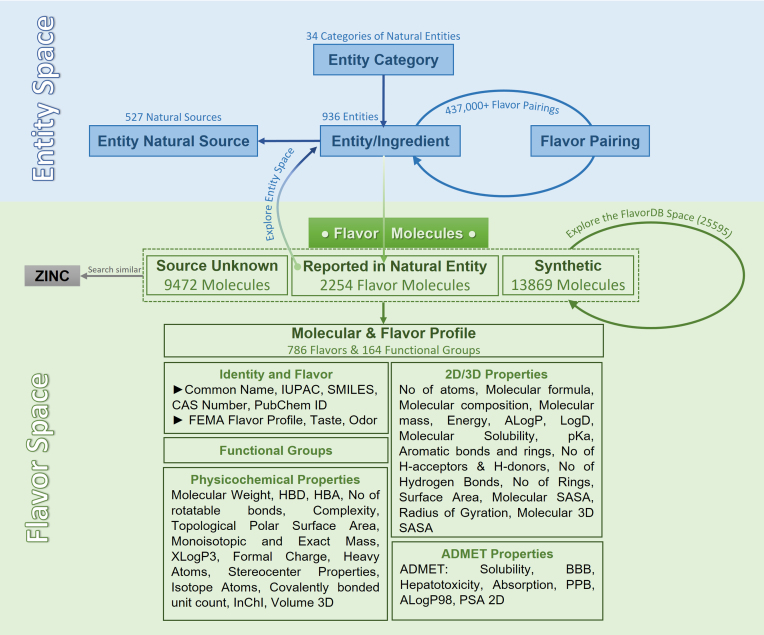

Figure 1.

FlavorDB is a seamless amalgamation of ‘entity space’ and ‘flavor space’. The resource provides a comprehensive dataset along with a user-friendly interface and interlinked search engines for exploring the flavor universe.

Among other sources, FlavorDB collates information from FooDB, Flavornet, SuperSweet and BitterDB to create a comprehensive repository of flavor molecules, flavor profiles, physicochemical properties and natural sources (Section S1, Supplementary Data). Compared to FooDB which has 2816 flavor compounds, FlavorDB covers 25,595 flavor molecules compiled from Fenaroli's Handbook of Flavor Ingredients and literature survey in addition to integrating data from all the above-mentioned sources. FlavorDB spans across 34 ingredient categories covering 936 ingredients of which 190 are unique. One of the features which sets FlavorDB apart from similar resources is that it presents information in a hierarchy of food category, ingredients, flavor molecules and their flavor profile, and chemical descriptors including functional groups and physicochemical properties. Through an extensive repertoire of ingredients and their constituent flavor molecules, FlavorDB also provides a tool for experimenting with flavor pairing. Thus, it offers an integrative platform for exploring the flavor space with the help of a feature-rich visual interface.

FlavorDB combines different dimensions of flavor constituting the ‘entity space’ and ‘flavor space’ (Figure 1). The former incorporates facets of ingredients which are entities from natural sources often used in food, whereas the latter represents molecules responsible for flavor sensation and their descriptors. By bringing relevant information under a single umbrella, FlavorDB provides a comprehensive dataset backed by a user-friendly interface, creative visualizations, and interlinked search engines for exploring features that contribute to the sensation of flavor. Thus, FlavorDB paves the way for an improved understanding of flavor perception arising out of complex interplay of flavor compounds with biological systems and allied applications.

DATABASE OVERVIEW

FlavorDB is a resource with extensive coverage of 25,595 flavor molecules (Figure 1). Among molecules listed in the database, 2254 have been reported to be found in 936 natural entities/ingredients. These natural ingredients have further been classified into 34 categories, and mapped to 527 distinct natural sources. An additional 13,869 compounds were identified as synthetic. For the remaining 9472 molecules, no specific source could be ascertained. The features provided as part of the detailed molecular and flavor profiles of these compounds have an impact on their taste and odor through gustatory and olfactory sensory mechanisms.

FlavorDB offers a user-friendly interface for querying and browsing flavor molecules, entities/ingredients, natural sources, as well as performing flavor pairing. Interactive data visualizations such as the flavor network and interlinked search options are provided to retrieve relevant information. Apart from searching via textual query or by drawing the chemical structure, FlavorDB also provides a ‘Visual Search’. Using this a user can interactively browse through the ingredient categories to access corresponding natural entities and subsequently obtain details of their flavor molecules.

For any flavor molecule, the resource also facilitates lookup for structurally similar molecules within the database as well as those commercially available from external sources (ZINC (14)). Thus, through a blend of the entity and flavor space along with a dynamic interface and visualizations, FlavorDB provides a wide spectrum of information facilitating insights into the flavor universe.

DATA COMPILATION

One of the primary motivations behind the creation of this resource was to map the space of molecules critical for the sensations of taste and smell. To begin with, a list of ingredients was created using (15–17), FooDB (http://foodb.ca) and arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03815, 2015. Each of the 936 ingredients were then manually classified into 34 categories: Additive, Animal Product, Bakery, Beverage, Beverage Alcoholic, Beverage Caffeinated, Cereal, Maize, Dairy, Dish, Essential Oil, Fish, Seafood, Flower, Fruit, Berry, Fruit Citrus, Fruit Essence, Fungus, Herb, Meat, Legume, Nut, Seed, Plant, Plant Derivative, Spice, Vegetable, Cabbage, Vegetable Fruit, Vegetable Gourd, Vegetable Root, Vegetable Stem, and Vegetable Tuber. Each entity was also mapped to its natural source, with a total of 527 unique sources being identified. The details of entities and their natural sources, related images, and scientific classification were obtained from Wikipedia using Python's BeautifulSoup4 library (https://www.crummy.com/software/BeautifulSoup) and MediaWiki's action API (MediaWiki The Free Wiki Engine).

The data of flavor molecules for each of these ingredients were compiled via flavor resources such as Fenaroli's handbook of flavor ingredients, previously reported data (16,17), FooDB (http://foodb.ca), arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03815 and literature survey (Also see Section S2, Supplementary Data). Common names, scientific name and synonyms of ingredients were used to query PubMed to obtain articles that reported their flavor molecules. Flavor molecules associated with entities/ingredients were thus curated from existing sources (15–17) (FooDB; http://foodb.ca, arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03815, 2015) and compiled manually. Molecules from Flavornet, BitterDB and SuperSweet were further included along with their flavor profiles (6,7,9). Additionally, information for 33 taste receptors (Sweet, Bitter, Sour, and Umami) and 1068 odor receptors is also available in FlavorDB. For each receptor, we provide its Uniprot ID, name, involvement in taste, and Uniprot link (18).

The chemical identifiers of molecules were obtained from various sources (FooDB; http://foodb.ca) (6,7,9,15,16) (Also see Section S2, Supplementary Data), and were standardized to procure their CAS (Chemical Abstract Service) numbers. CAS numbers were then mapped to their corresponding PubChem IDs, as the former are often degenerate with multiple CAS numbers pointing to the same molecule, and some pointing to multiple molecules. Thus, PubChem ID was used as the unique primary key for every flavor molecule. Using the PubChem ID, compound identifiers (such as common name, IUPAC, Canonical SMILES), physicochemical properties and 2D images were obtained from PubChem REST API (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pug_rest/PUG_REST.html). The flavor profile of the molecule (Flavor Profile, FEMA Flavor Profile, FEMA Number, Taste, and Odor) was created by compiling information from FooDB (http://foodb.ca), Flavornet (6), SuperSweet (9), BitterDB (7) and PubChem.

Further 2D/3D, ADMET and physicochemical properties as well as Mol2 files for all 25,595 molecules were obtained using Discovery Studio 4.0 (DS4.0; Accelrys Inc.). The functional groups were obtained using Checkmol software (19). Functional group refers to an atom, or a group of atoms that have similar chemical properties whenever they occur in different compounds (20). Thus, it defines the characteristic physical and chemical properties of families of organic compounds.

Please refer to Supplementary Figures S1, S2, S3 and S4 in Supplementary Data for the statistics of entities, categories, flavor molecules, their flavors and functional groups.

DATABASE ARCHITECTURE AND WEB INTERFACE

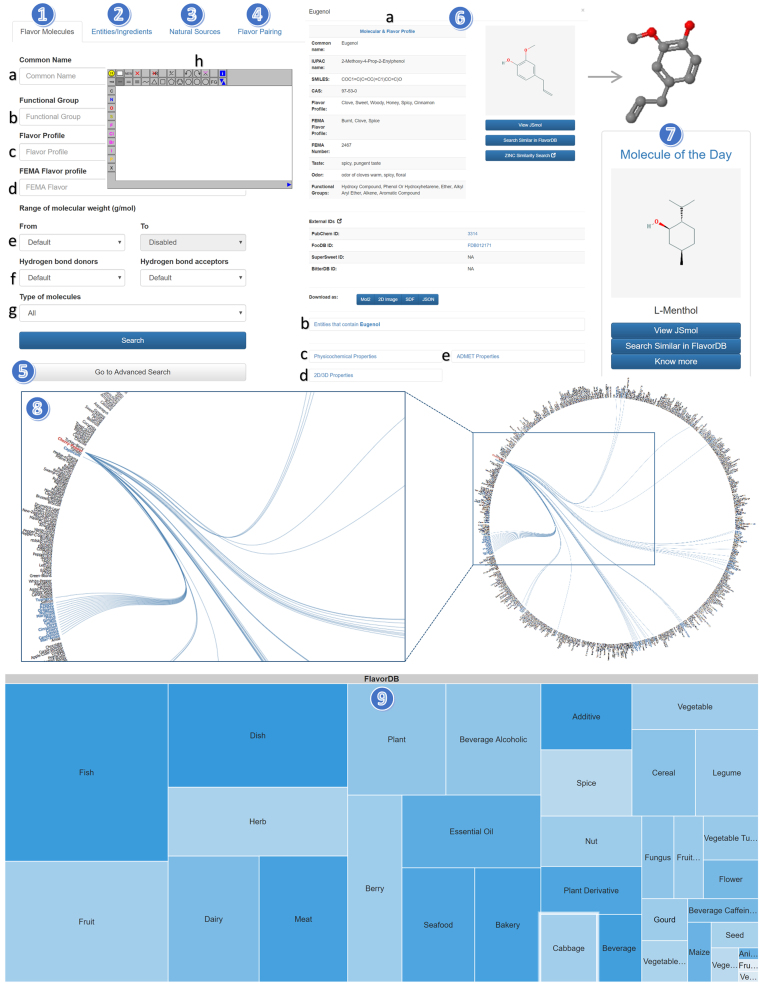

FlavorDB facilitates easy comprehension of complex interrelations among flavor molecules, entities/ingredients and their natural sources (Figure 2; also see Figure S5 of Supplementary Data). Interactive data visualizations and a wide variety of user-friendly searches provide quick access to desired information. The following utilities and applications in FlavorDB enable visual explorations of ‘flavor space’ and ‘entity space’ to get insights into the flavor universe.

Figure 2.

Schematic of FlavorDB user interface highlighting features for searching and graphical navigation of data. (1) Flavor Molecule Search, (2) Entity/Ingredient Search, (3) Natural Source Search, (4) Flavor Pairing, (5) Advanced Search, (6) Molecular & Flavor Profile (including features for finding related entities, searching for structurally similar molecules, external link-outs and data download), (7) Molecule of the Day, (8) The Flavor Network and (9) Visual Search.

The flavor network

Flavor Network visualizes the graph of flavor-sharing across all entities/ingredients. To make it easier to observe flavor-sharing within and across categories, the entities are grouped category-wise and are spaced out along the circumference. To address dense pattern of interrelationships due to abundance of sharing, the backbone network showing statistically significant edges is depicted (21). Clicking on an entity shows its association with other entities by virtue of shared flavor molecules, thereby enabling search for similarities among seemingly disparate entities. The Flavor Network was implemented with the D3.js JavaScript library (https://d3js.org).

Visual search

Visual Search, implemented with the Google Charts library (http://developers.google.com/chart), provides an interactive way of exploring FlavorDB. At the top of the hierarchy, it displays all 34 ingredient categories as boxes. The size of each box is determined by the number of unique flavor molecules present in that category. Greater the number of molecules, larger the size of the box. Clicking through any of the categories, one can navigate to its constituent ingredients and their respective flavor profiles. Thus, visual search enables multi-level, open-ended exploration of FlavorDB.

Molecular search

By virtue of extensive molecular and flavor features provided in FlavorDB, ‘Molecular Search’ forms a key query mechanism. It facilitates querying on the basis of a host of features including Common Name, Functional Group, FEMA Flavor, Molecular Weight, Number of Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors, and Type of Molecules (Natural, Synthetic, Unknown). Additionally, the JSME Molecule Editor enables search based on structural similarity (22). The editor facilitates creation of molecules using SMILES, MOL or SDF files. Structurally similar compounds can also be found using the ‘Search Similar in FlavorDB’ button provided on the molecules’ profile page.

Molecular search yields matching flavor compounds with detailed ‘molecular and flavor profile’. A 3D visualization of the molecule is provided with the JSmol library along with an external link to PubChem. Further an option for downloading the molecule in different formats (MOL2, SMILES, 2D images) is also available. The flavor molecules can be filtered using search and sort functionality provided by ‘data tables’ plugin.

The algorithm for performing structural similarity computes molecular fingerprints (FP2) of all flavor molecules using OpenBabel (11). For any molecular structure that is queried, its fingerprint is computed using an OpenBabel protocol and is compared with the database using the Tanimoto coefficient of structural similarity. Molecules with at least 30% similarity are returned. FlavorDB also facilitates browsing all 25,595 flavor molecules by doing a null search (no constraints; all query fields empty). ‘Molecule of the Day’ feature offers a peek into the flavor universe, from where the user can start exploring the resource.

Advanced search

Advanced search provides an option for refined search by querying FlavorDB data on the basis of a variety of molecular properties (number of rings, rotatable bonds, energy, surface area etc.) apart from those provided in basic search. For numeric fields either a range or discrete values can be provided as a query.

Entity and natural source search

These searches facilitate querying on the basis of ‘Entity/Ingredient Name’ as well as ‘Category Name’ to retrieve detailed information of entity, category, natural source, scientific classification, Wiki page link, synonyms, images, and flavor molecules associated with the entity. Additionally, we facilitate search based on synonyms, knowing that many ingredients are often known by a variety of alternative names. For example, to search for ‘Eggplant’, one may as well search by either ‘Aubergine’ or ‘Brinjal’. All text search fields are assisted by jQuery UI autocomplete.

Flavor pairing

‘Flavor Pairing’ (also known as ‘Food Pairing’) is a heuristic with empirical evidence (15,16), (arXiv preprint arXiv:1505.00155, 2015), used for finding ingredient pairs that are expected to go well together in a recipe/food product. On the foundation of extensive repertoire of 936 entities and their constituent flavor molecules (2254), ‘Flavor Pairing’ tool provides a powerful engine for spanning through >437,000 pairings to reveal flavor profile overlaps across categories and disparate entities. The app provides pairing results through interactive visualization for easy comprehension. Detailed analysis yields the number of shared flavor molecules between the queried entity and all the other entities having at least one shared flavor molecule. The results can be further filtered using data tables to probe the list of shared flavor molecules.

Webserver tech stack

FlavorDB has been designed as a Relational Database using MySQL (https://www.mysql.com). The webserver has been built using the Python web development framework, Django (https://www.djangoproject.com). Django has a built in ORM (Object Relational Mapper) for querying the database, thus optimizing queries and making it easier to perform complex queries, apart from reducing the development period. The front-end has been built using HTML, CSS and JavaScript. The jQuery, Bootstrap, D3.js and Google Charts libraries were used to add to the functionality of FlavorDB. An Apache HTTP Server has been used to route requests to the Django app and to enable data compression for faster page load times. The site is best viewed in latest versions of Google Chrome, Firefox, Opera, Internet Explorer, and Microsoft Edge.

EXAMPLES

Below we provide a few case studies illustrating the utility of FlavorDB for various applications.

Applications for Flavor/Food pairing

The food pairing principle suggests that ingredients which taste similar tend to be used together in recipes (23). Historically practiced on a trial-and-error basis, food pairing has relied heavily on human judgment and the intuition of food connoisseurs. Evidence-based understanding of rules that dictate food choices can facilitate informed experiments to pair ingredients in a recipe. While many Western cuisines are reported to be characterized with ‘uniform food pairing’, Indian cuisine tends to follow ‘contrasting food pairing’ pattern (15,16) (arXiv preprint arXiv:1505.00155, 2015, arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03815, 2015). Based on data of ingredients and flavor molecules, FlavorDB offers an app by which users can experiment with food pairing of desired ingredients.

Let's consider the case where a user wants to find a substitute for oregano. Using the Flavor Network, one can quickly get an overview of ingredients that share flavor molecules with oregano. Via the Flavor Pairing app, it can be observed that oregano and thyme have the most number of common molecules. Hence, by virtue of uniform food pairing, thyme can be a possible substitute for oregano. This example demonstrates the utility of different features of FlavorDB for making informed decisions on flavor pairing and choice of ingredients.

Searching for drug-like compounds

Find molecules structurally similar to a compound satisfying Lipinski's rule of five. This example demonstrates use of FlavorDB’s ‘Advanced Search’ and ‘Structural Similarity Search’ features to find molecules matching desired chemical properties. Lipinski's rule is a heuristic to evaluate drug-likeness; the suitability of a chemical compound to have pharmacological or biological activity making it a likely candidate for orally active drug. It states that, an orally active drug has no more than one violation of the following criteria: no more than five hydrogen bond donors; no more than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors; Molecular mass less than 500 Da; an octanol–water partition coefficient (log P) not >5.

Using the above mentioned criteria in the ‘Advanced Search’, one can search for molecules that satisfy Lipinski's rule. This query can be refined further by using the structural search provided through the JSME tool, to find drug-like compounds that are structurally related to a certain compound. As an example, one may specify the conditions for Lipinski's rule in the ‘Advanced Search’ and draw the chemical structure for Pyridine. The resulting search returns all molecules that are potentially suitable for being tested as a drug, ranked in descending order of structural similarity with Pyridine.

Finding flavor molecules similar to any desired compound

Allicin (SMILES: O=S(SC\C=C)C\C=C) is one of the primary molecules present in garlic. Using the structural search, one can get a list of similar molecules in FlavorDB. The top result for this example is Diallyl Disulfide with 66.7% similarity. Interestingly, as reflected in its ‘Molecular and Flavor Profile’, Diallyl Disulfide has a ‘sharp, garlic taste’. Thus it can be a possible substitute for Allicin and used as a scaffold to create a synthetic garlic flavor. One may also search for flavor molecules matching a particular FEMA flavor term and/or functional group among naturally occurring as well as synthetic compounds.

Exploring flavor properties of ingredients

Wasabi is empirically known to have a pungent odor. Using the ‘Entity Search’ option, it can be discovered that there are five known flavor molecules for Wasabi in FlavorDB. Of these, one molecule, Allyl Isothiocyanate is reported to exhibit characteristics of a ‘very pungent’ odor. It can be speculated that the pungent smell of wasabi is primarily due to the presence of Allyl Isothiocyanate.

The above examples illustrate how FlavorDB and its features can be interactively used to make data-driven decisions that cater to various aspects of flavor.

SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

Study of molecules and mechanisms involved in flavor sensation has been of interest for its applications for food and fragrances (1–13) (http://www.pherobase.com). Contributing to the efforts on compilation of molecules from food and their flavors, FlavorDB provides a detailed perspective into the ‘entity space’, ‘flavor space’ and the latent connections between the two. In doing so, it lays down the foundation for conducting data driven analysis which can aid in building applications meant for molecular gastronomy, culinary food pairing, novel recipe generation, aroma blending and predicting odor from chemical features (24–26).

Despite our best efforts, FlavorDB is not an exhaustive repository of all flavor molecules and ingredients. Our data on flavor molecules of an ingredient is limited by the availability of information about them from literature survey. Similarly, the ingredients represented in the database are not exhaustive in themselves as their choice is limited by the reports of flavor compounds. Also, at present the database focuses on flavor profiles of natural ingredients and thus, the crux of our flavor space is made up of flavor molecules from natural sources.

In future, we intend to increase the coverage of flavor molecules and look for their latent effects on human health. Our endeavor is to integrate aspects of flavor profiles with those of entities and molecules that has hitherto been unexplored.

AVAILABILITY

FlavorDB is available at http://cosylab.iiitd.edu.in/flavordb

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

G.B. thanks the Indraprastha Institute of Information Technology (IIIT-Delhi) for providing computational facilities and support. N.G., A.S., R.T., S.D., N.S., S.S. and K.K. were Summer Research Interns in Dr. Bagler's lab at the Center for Computational Biology, and are thankful to IIIT-Delhi for the support and fellowship. A.I., A.G. and S.A., M.Tech. (Computational Biology) students, thank IIIT-Delhi for the fellowship. R.N.K., R.B. and R.K. thank the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India and Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur for the senior research fellowship.

Footnotes

Present address: Ganesh Bagler, Center for Computational Biology, Indraprastha Institute of Information Technology (IIIT-Delhi), New Delhi 110020, India.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

The open access publication charge for this paper has been waived by Oxford University Press - NAR.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fisher C., Scott T.. Food Flavours: Biology and Chemistry Royal Society of Chemistry. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shepherd G. Neurogastronomy – How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why it Matters. 2013; Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malnic B., Hirono J., Sato T., Buck L.B.. Combinatorial receptor codes for odors. Cell. 1999; 96:713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mouritsen O.G. The science of taste. Flavour. 2015; 4:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Newcomb R.D., Ohla K.. The genetics and neuroscience of flavour. Flavour. 2013; 2:17. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arn H., Acree T.E.. Flavornet: a database of aroma compounds based on odor potency in natural products. Dev. Food Sci. 1998; 40:27. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wiener A., Shudler M., Levit A., Niv M.Y.. BitterDB: a database of bitter compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:413–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dunkel M., Schmidt U., Struck S., Berger L., Gruening B., Hossbach J., Jaeger I.S., Effmert U., Piechulla B., Eriksson R. et al. SuperScent – a database of flavors and scents. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:291–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahmed J., Preissner S., Dunkel M., Worth C.L., Eckert A., Preissner R.. SuperSweet-A resource on natural and artificial sweetening agents. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:D377–D382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scalbert A., Andres-Lacueva C., Arita M., Kroon P., Manach C., Urpi-Sarda M., Wishart D.. Databases on food phytochemicals and their health-promoting effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011; 59:4331–4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rothwell J.A., Perez-Jimenez J., Neveu V., Medina-Remón A., M’Hiri N., García-Lobato P., Manach C., Knox C., Eisner R., Wishart D.S. et al. Phenol-Explorer 3.0: a major update of the Phenol-Explorer database to incorporate data on the effects of food processing on polyphenol content. Database. 2013; 2013:bat070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jensen K., Panagiotou G., Kouskoumvekaki I.. NutriChem: a systems chemical biology resource to explore the medicinal value of plant-based foods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:D940–D945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neveu V., Perez-Jimenez J., Vos F., Crespy V., du Chaffaut L., Mennen L., Knox C., Eisner R., Cruz J., Wishart D. et al. Phenol-Explorer: an online comprehensive database on polyphenol contents in foods. Database. 2010; 2010:bap024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sterling T., Irwin J.J.. ZINC15—ligand discovery for everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015; 55:2324–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jain A., Rakhi N.K., Bagler G.. Analysis of food pairing in regional cuisines of India. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0139539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahn Y.-Y., Ahnert S.E., Bagrow J.P., Barabási A.-L.. Flavor network and the principles of food pairing. Sci. Rep. 2011; 1:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burdock G.A. Fenaroli's handbook of flavor ingredients. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wasmuth E.V., Lima C.D.. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 45:1–12.27899559 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haider N. Functionality pattern matching as an efficient complementary structure/reaction search tool: an open-source approach. Molecules. 2010; 15:5079–5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. IUPAC Compendium of chemical terminology. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Serrano M.A., Boguna M., Vespignani A.. Extracting the multiscale backbone of complex weighted networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106:6483–6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bienfait B., Ertl P.. JSME: a free molecule editor in JavaScript. J. Cheminform. 2013; 5:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blumenthal H. The Big Fat Duck Cookbook Bloomsbury Publishing. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keller A., Gerkin R.C., Guan Y., Dhurandhar A., Turu G., Szalai B., Mainland J.D., Ihara Y., Yu C.W., Wolfinger R. et al. Predicting human olfactory perception from chemical features of odor molecules. Science. 2017; 355:820–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Spence C., Hobkinson C., Gallace A., Fiszman B.P.. A touch of gastronomy. Flavour. 2013; 2:14. [Google Scholar]

- 26. This H. Molecular gastronomy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002; 41:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.