Abstract

DIANA-TarBase v8 (http://www.microrna.gr/tarbase) is a reference database devoted to the indexing of experimentally supported microRNA (miRNA) targets. Its eighth version is the first database indexing >1 million entries, corresponding to ∼670 000 unique miRNA-target pairs. The interactions are supported by >33 experimental methodologies, applied to ∼600 cell types/tissues under ∼451 experimental conditions. It integrates information on cell-type specific miRNA–gene regulation, while hundreds of thousands of miRNA-binding locations are reported. TarBase is coming of age, with more than a decade of continuous support in the non-coding RNA field. A new module has been implemented that enables the browsing of interactions through different filtering combinations. It permits easy retrieval of positive and negative miRNA targets per species, methodology, cell type and tissue. An incorporated ranking system is utilized for the display of interactions based on the robustness of their supporting methodologies. Statistics, pie-charts and interactive bar-plots depicting the database content are available through a dedicated result page. An intuitive interface is introduced, providing a user-friendly application with flexible options to different queries.

INTRODUCTION

Accurate characterization of microRNA (miRNA) targets is considered fundamental to elucidate their regulatory roles. miRNAs are short (∼23 nt) single-stranded non-coding RNA molecules that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression, through target cleavage, degradation and/or translational suppression (1,2).

Over the last 15 years, a multitude of in silico and experimental procedures have been developed aiming to determine the miRNA interactome (1,3). Currently, high-throughput techniques have enabled the identification of novel experimentally supported miRNA–gene interactions in a transcriptome-wide scale (4). The broad use of these experimental methodologies has advanced miRNA target recognition toward the gradual substitution of related computational approaches.

The information on validated miRNA targets is dispersed in a great number of publications and raw datasets from high-throughput experiments. To this end, several repositories have been developed aiming to catalog experimentally supported interactions and further sustain miRNA-related studies (5).

Experimental methodologies

The experimental techniques that are utilized to identify novel miRNA targets and validate predicted interactions can significantly differ in their accuracy and robustness. They are mainly divided into low- and high-throughput experiments according to the amount of information they produce. In low-throughput techniques, reporter gene assays focus on the recognition of the exact miRNA-binding location, while indirect methodologies like quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), western blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay infer interactions by taking into consideration the reduction of mRNA or protein concentration (3). High-throughput techniques, such as microarrays and proteomics are the extension of low-yield methodologies, enabling the indirect detection of numerous miRNA targets. Current advancements in next-generation sequencing technologies have radically changed the characterization of the miRNA interactome (4). RNA immunoprecipitation combined with sequencing (RIP-seq) constitutes one of the first experiments to enable the identification of RNAs bound by a protein of interest (6). Recently, Ribosome profiling sequencing (RPF-seq) experiments have been proposed as a sensitive and quantitative protocol, able to measure the efficiency and speed of translation, as well as the ribosome occupancy per transcript. This methodology allows the evaluation of miRNA-mediated translational repression by the analysis of captured ribosome-bound transcripts (7). These procedures are coupled with overexpression or knockdown of a specific miRNA in order to detect genes quantitatively affected by miRNA expression perturbations. Crosslinking and immunoprecipitation sequencing (CLIP-seq) methodologies focus on the transcriptome-wide recognition of RNA–protein-binding regions and are usually complemented with RNA expression experiments (8). AGO CLIP-seq methodologies inaugurated a new era in miRNA research, providing unprecedented accuracy and multitude of miRNA targets in a transcriptome-wide scale. Recent modified versions of the later techniques, such as CLEAR-CLIP (9) and CLASH (10) protocols, include an extra ligation step which links miRNA molecules with their respective target-binding site, resulting in hundreds of chimeric miRNA–mRNA fragments.

Databases indexing miRNA–gene interactions

The emergence of databases devoted to the cataloging of miRNA–gene interactions has played a pivotal role in the miRNA research field. miRTarBase (11) constitutes an extensive repository, integrating ∼350 000 miRNA targets supported from low-/high-throughput experiments for several species. It provides information regarding the miRNA, the targeted gene and the binding site location, while its sixth version has been enhanced with miRNA/mRNA profiles retrieved from the Cancer Genome Atlas (12). miRecords (13) and miR2Disease (14) are smaller and not continuously updated repositories. They contain ∼3000 validated interactions from low-yield techniques, while the latter hosts manually curated miRNA targets combined with information for miRNA deregulation in human diseases. Other repositories, such as StarBase (15) and CLIPZ (16), substantially differ in their scope, as they provide RNA-binding protein regions from different CLIP-seq datasets.

In this publication, we present DIANA-TarBase v8.0, an extensive repository with ∼670 000 unique experimentally supported miRNA–gene interactions. This collection of targets, supported by distinct methodologies, cell types/tissues and experimental conditions, corresponds to >1 million miRNA–gene entries. TarBase was initially released in 2006, constituting the first database to catalog experimentally validated miRNA interactions and since then is constantly updated. The current version has been enhanced with a large compilation of high quality miRNA-binding events derived from chimeric fragments, reporter gene assay and CLIP-seq experiments. More than 200 high-throughput experiments followed by perturbation of a specific miRNA have been analyzed and integrated in the database. This extension provides an increase of ∼200 000 interactions and ∼300 000 entries since the previous version (8). A concise description of TarBase v8.0 is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. TarBase v8.0 entries.

| TarBase v8.0 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Database | Total entries | >1 080 000 |

| Entries from low-yield methods | 10 339 | |

| Entries from high-throughput methods | ∼1 069 000 | |

| Cell types | 516 | |

| Tissues | 85 | |

| Publications | 1208 | |

| Support from direct experiments | miRNA–gene entries | ∼790 300 |

| miRNAs | 1761 | |

| Targeted genes | 27 613 | |

| Publications | 968 | |

| Analyzed high-throughput datasets | Datasets | 353 |

| Conditions | ∼230 | |

| Publications | 102 | |

| Experimental methods | Description of major classes | Reporter genes, western blot, qPCR, proteomics, biotin miRNA tagging, CLIP-seq, CLEAR-CLIP, CLASH, CLIP-chimeric, IMPACT-seq, AGO-IP, RPF-seq, RIP-seq, Degradome, RNA-seq, TRAP, microarrays, other |

| Interface | Data visualization | Re-designed interface, support of specific queries, browsing mode, ranking system, customizable sorting of results, advanced interactive statistics, advanced filtering options, cell type/tissue combinations, detailed meta-data, interconnection with DIANA-tools, ENSEMBL integration |

Statistics regarding the total entries, miRNA–gene interacting pairs derived from low-/high-throughput methodologies, distinct cell types/tissues and curated publications are provided. The number of analyzed datasets and unique studied conditions are presented for high-throughput experiments. The incorporated low-/high-throughput experimental techniques, as well as interface improvements are reported. Newly incorporated experimental methods and interface advancements are marked as bold.

A new browsing-mode is introduced which facilitates navigation through this wealth of information. Users can easily obtain the bulk of positive and/or negative miRNA–gene interactions per species, methodology, cell type, tissue without performing a specific miRNA/gene query. The novel ranking system aims to further assist researchers by sorting interactions based on the robustness of their supporting experimental methodologies. Statistics, advanced pie-charts and bar-plots portraying various aspects of the database content are made available to users through a dedicated results page.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collected data

In the updated database version, ∼419 publications have been manually curated and added, while >245 high-throughput datasets harboring (in-)direct interactions have been collected and/or analyzed. Emphasis was placed on extracting extensive meta-data to accompany indexed entries. Each miRNA–target interaction is coupled with information regarding the relevant publications and methodologies, tissues, cell types as well as the positive or negative type of regulation. In the case of direct techniques, the exact miRNA-binding locations have been archived and complementary information of the cloning primers and the targeted regulatory regions on the transcripts (e.g. 3′ Untranslated Region - 3′ UTR, coding sequence - CDS) are included. Interactions supported from high-throughput experiments, have been extracted either from relevant publications or from the analysis of raw libraries retrieved from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (17) and DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) (18) repositories. Descriptions regarding the experimental procedures/conditions are also available to the users.

Analysis of high-throughput datasets

High-throughput experiments were analyzed to retrieve gene expression alterations upon specific miRNA treatment. Raw microarray datasets have been processed with a standardized in silico pipeline developed in R language (19). In Affymetrix arrays, Robust Multi-Array Average from Bioconductor packages affy (20) or oligo (21) was utilized to perform probe set summarization. Agilent and Illumina microarray datasets were background corrected using normexp method and quantile normalization (22). Probe sets were mapped to Ensembl gene IDs (23) utilizing chip-specific Bioconductor R packages (24). Differential expression was assessed with limma (22), using moderated t-statistics and adjusting the associated P-values with Benjamini–Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate. The log2 fold change values of probe sets mapped on the same gene were averaged to calculate its expression alteration. Positive and negative interactions from each set were inferred using a ±0.5 log2 fold change threshold, according to the perturbation type.

Processed RPF-seq, RNA-seq and RIP-seq libraries, submitted to specific miRNA treatment were collected from the respective publications. Positive/negative miRNA interactions were formed from genes presenting >10 Reads per Kilobase per Million reads (RPKM) and >50% expression change.

AGO-CLIP-seq methodologies have been analyzed as described in the previous TarBase version (8).

Database statistics

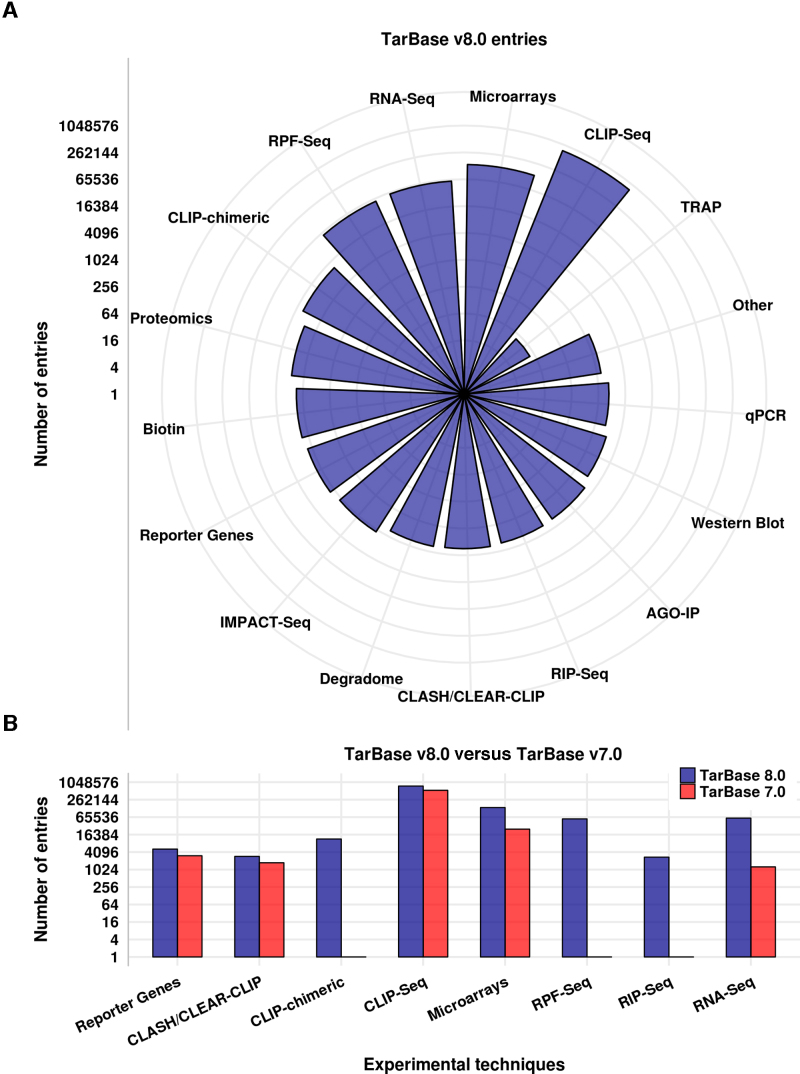

DIANA-TarBase v8.0 caters more than one million entries, corresponding to the largest compilation of experimentally supported miRNA targets. This collection of miRNA–gene interactions has been derived from experiments employing >33 distinct low-yield and high-throughput techniques, spanning 85 tissues, 516 cell types and ∼451 experimental conditions from 18 species (Figure 1A). Approximately 1200 publications were manually curated and >350 high-throughput datasets have been analyzed. The new database version incorporates an assortment of positive and negative direct miRNA interactions. It comprises >10 000 interactions derived from specific techniques. Approximately 5100 of these miRNA targets are verified by reporter gene assays, extracted from ∼950 publications, providing a 1.6-fold increase compared to relevant entries in TarBase v7.0. More than 14 000 direct miRNA–mRNA chimeric fragments defined from CLASH and CLEAR-CLIP experiments, as well as from a previous meta-analysis of published AGO-CLIP datasets (25), have been integrated to the repository. Approximately 90 000 new entries were generated from the analysis of additional AGO CLIP-seq libraries from three studies. More than 233 000 interactions have been extracted from miRNA-specific transfection/knockdown microarray, RPF-seq, RIP-seq and RNA-seq experiments which were performed in 28 tissues and 82 cell types under 206 experimental conditions. Updated entries derived from the aforementioned methodologies are summarized in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

TarBase entries divided per methodology. Values are plotted in log2 scale. Each grid line corresponds to quadrupling of indexed miRNA interactions. (A) Total miRNA–gene entries incorporated in TarBase v8.0. (B) Comparison of TarBase v8.0 and TarBase v7.0 entries.

Interface

Querying the database

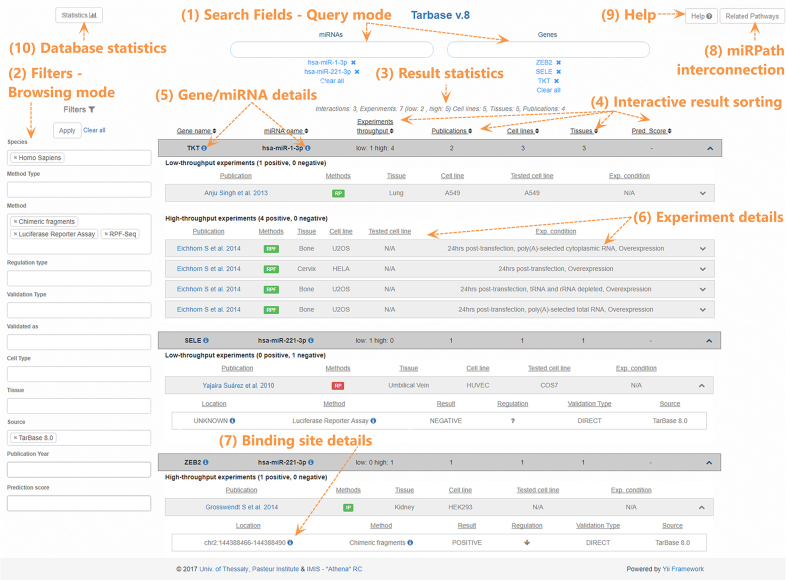

A new relational schema, developed in PostgreSQL, is introduced to host TarBase v8.0 data. The database interface has also been redesigned using the Yii 2.0 PHP framework and enhanced to provide an intuitive user-friendly application as well as flexible options to different queries (Figure 2). Users can retrieve interactions by performing a query with miRNA and/or gene names. Identifiers from ENSEMBL (23) and miRBase (26) are supported. Positive and/or negative miRNA targets can be retrieved through the combination of distinct filters such as experimental methodology, cell type and tissue according to the user’s needs. Results can be sorted in ascending or descending order based on gene and/or miRNA names as well as on the number of experiments, publications and cell types/tissues supporting these interactions. Detailed meta-data including the binding location and experimental conditions are displayed in the relevant result sections.

Figure 2.

Snapshot depicting the DIANA-TarBase v8.0 interface. Users can apply a query with miRNA and/or gene names (1) or navigate in the database content through combinations of the filtering criteria (2). Positive/negative interactions can be refined with a series of filtering options including species, tissues/cell types, methodologies, type of validation (direct/indirect), database source, publication year as well as in silico predicted score (2). Brief result statistics are promptly calculated (3). Interactions can be sorted in ascending or descending order based on gene and/or miRNA names, on the number of experiments, publications and cell types/tissues supporting them (4). Gene and miRNA details, complemented with active links to Ensembl, miRBase and the DIANA disease tag cloud, are provided (5). Details regarding the experimental procedures such as the methodology, cell type/tissue, experimental conditions and link to the actual publication are presented (6). Methods are color-coded, with green and red portraying validation for positive and negative regulation, respectively. Interactions are also accompanied by miRNA-binding site details (7). Links to DIANA-miRPath functional analysis resource (8) and to an informative Help section (9) are also available. Users can navigate to the separate database statistics page (10).

Ranking system

A novel ranking system has been incorporated in the interface. miRNA targets are by default sorted according to the robustness of the respective experimental techniques. In brief, miRNA–gene interactions determined from low-throughput experiments are reported first, followed by those derived from high-throughput techniques. More precisely, miRNA-binding events retrieved from reporter gene assays, the gold standard of methodologies in miRNA target recognition, are prioritized, followed by those defined from any other low-yield technique. Direct interactions inferred from chimeric fragments are subsequently presented, followed by those determined from CLIP-seq methods. miRNA targets supported from any other indirect miRNA-specific transfection/knockdown high-throughput technique are finally displayed. In cases of miRNA–target pairs derived from the same category of methods, ranking is performed based on the number of distinct experiments they have been validated with.

Browsing mode

A novel aspect in the new interface is the browsing mode (Figure 2). Users can easily retrieve the top targets (up to a maximum of 3000) without applying any specific query. Positive or negative interactions can be obtained based on different combinations of the filtering criteria including species, tissues/cell types and methodologies.

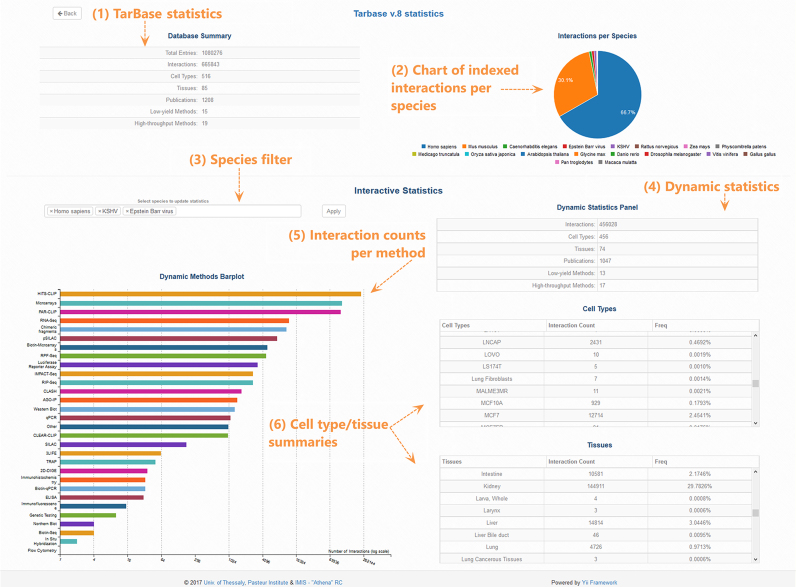

Advanced statistics

DIANA-TarBase v8.0 also provides statistics, advanced interactive pie-charts and bar plots, implemented using the D3.js JavaScript library, to portray the database content and extent for the different species (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Screenshot depicting DIANA-TarBase statistics page. The number of interactions, cell types/tissues, publications and low-/high-throughput methodologies are summarized at the top of the page (1). A pie-chart portraying the database content per species is provided (2). The user can select any species combination (3) to obtain relevant statistics (4). The bar-plot (5) and tables (6) at the end of the page show the number of interactions (log2-scaled) per methodology and the cell-type/tissue frequencies respectively. They are also dynamically populated depending on the user’s choice of species.

Database interconnections

Since the sixth version, DIANA-TarBase has been integrated in ENSEMBL (23). Interactions accompanied with the exact binding location can be viewed in the ENSEMBL genome browser via the dedicated ‘TarBase’ track. The database is also seamlessly interconnected with other available DIANA-tools, including microT-CDS (27) for in silico identification of miRNA targets, LncBase v2.0 (28) for the display of miRNA–lncRNA interactions and DIANA-miRPath v3.0 (29) for functional characterization of miRNAs.

Additionally to the ∼1 million entries indexed in TarBase, miRNA targets retrieved from other relevant databases, including miRTarBase (11) and miRecords (13), are also provided to users. These entries are disregarded from database statistics.

CONCLUSION

Comprehensive cataloging of the miRNA interactome is considered pivotal to miRNA research efforts. DIANA-Tarbase v8.0 is the first new version since the tenth anniversary of the database inauguration and showcases the continuous effort of indexing hundreds of thousands of miRNA targets. It comprises ∼1 million entries, the largest compilation of miRNA–gene interactions compared to any relevant database. The new re-designed interface facilitates the extraction of miRNA interactions derived from >33 experimental methodologies, applied to ∼600 distinct cell types/tissues under ∼451 experimental conditions. The direct interconnection with DIANA-miRPath v3.0 (29), simplifies the investigation of miRNA exerted regulation in physiological/pathological molecular pathways. DIANA-TarBase v8.0 is an important asset to the research community, empowering experimental investigations as well as in silico miRNA-related exploratory studies.

FUNDING

Fondation Santé Grant (to A.G.H.); General Secretariat of Research and Technology, Greece Grant (‘KRIPIS’) (to T.D.); Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (ELIDEK) PhD Fellowship; IKY Foundation PhD Fellowship in the framework of the Hellenic Republic-Siemens Settlement Agreement. Funding for open access charge: General Secretariat of Research and Technology, Greece Grant (‘KRIPIS’) (to T.D.).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vlachos I.S., Hatzigeorgiou A.G.. Online resources for miRNA analysis. Clin. Biochem. 2013; 46:879–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huntzinger E., Izaurralde E.. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011; 12:99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomson D.W., Bracken C.P., Goodall G.J.. Experimental strategies for microRNA target identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:6845–6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goodwin S., McPherson J.D., McCombie W.R.. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016; 17:333–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vlachos I.S., Georgakilas G., Tastsoglou S., Paraskevopoulou M.D., Karagkouni D., Hatzigeorgiou A.G.. De Pietri Tonelli D. Computational challenges and -omics approaches for the identification of miRNAs and targets. Essentials of Noncoding RNA in Neuroscience. 2017; Boston: Academic Press; 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cloonan N., Forrest A.R., Kolle G., Gardiner B.B., Faulkner G.J., Brown M.K., Taylor D.F., Steptoe A.L., Wani S., Bethel G.. Stem cell transcriptome profiling via massive-scale mRNA sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2008; 5:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eichhorn S.W., Guo H., McGeary S.E., Rodriguez-Mias R.A., Shin C., Baek D., Hsu S.-H., Ghoshal K., Villén J., Bartel D.P.. mRNA destabilization is the dominant effect of mammalian microRNAs by the time substantial repression ensues. Mol. Cell. 2014; 56:104–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vlachos I.S., Paraskevopoulou M.D., Karagkouni D., Georgakilas G., Vergoulis T., Kanellos I., Anastasopoulos I.L., Maniou S., Karathanou K., Kalfakakou D. et al. DIANA-TarBase v7.0: indexing more than half a million experimentally supported miRNA:mRNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:D153–D159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore M.J., Scheel T.K., Luna J.M., Park C.Y., Fak J.J., Nishiuchi E., Rice C.M., Darnell R.B.. miRNA-target chimeras reveal miRNA 3 [prime]-end pairing as a major determinant of Argonaute target specificity. Nat. Commun. 2015; 6:8864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Helwak A., Kudla G., Dudnakova T., Tollervey D.. Mapping the human miRNA interactome by CLASH reveals frequent noncanonical binding. Cell. 2013; 153:654–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chou C.-H., Chang N.-W., Shrestha S., Hsu S.-D., Lin Y.-L., Lee W.-H., Yang C.-D., Hong H.-C., Wei T.-Y., Tu S.-J.. miRTarBase 2016: updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 44:D239–D247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weinstein J.N., Collisson E.A., Mills G.B., Shaw K.R.M., Ozenberger B.A., Ellrott K., Shmulevich I., Sander C., Stuart J.M., Network C.G.A.R.. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013; 45:1113–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiao F., Zuo Z., Cai G., Kang S., Gao X., Li T.. miRecords: an integrated resource for microRNA–target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008; 37:D105–D110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang Q., Wang Y., Hao Y., Juan L., Teng M., Zhang X., Li M., Wang G., Liu Y.. miR2Disease: a manually curated database for microRNA deregulation in human disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008; 37:D98–D104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li J.-H., Liu S., Zhou H., Qu L.-H., Yang J.-H.. starBase v2. 0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein–RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 42:D92–D97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khorshid M., Rodak C., Zavolan M.. CLIPZ: a database and analysis environment for experimentally determined binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 39:D245–D252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barrett T., Wilhite S.E., Ledoux P., Evangelista C., Kim I.F., Tomashevsky M., Marshall K.A., Phillippy K.H., Sherman P.M., Holko M.. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets—update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 41:D991–D995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kodama Y., Shumway M., Leinonen R.. The sequence read archive: explosive growth of sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 40:D54–D56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. R Development Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found. Stat. Comp. 2016; Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gautier L., Cope L., Bolstad B.M., Irizarry R.A.. affy–analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004; 20:307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carvalho B.S., Irizarry R.A.. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26:2363–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C.W., Shi W., Smyth G.K.. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flicek P., Amode M.R., Barrell D., Beal K., Brent S., Carvalho-Silva D., Clapham P., Coates G., Fairley S., Fitzgerald S.. Ensembl 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 40:D84–D90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huber W., Carey V.J., Gentleman R., Anders S., Carlson M., Carvalho B.S., Bravo H.C., Davis S., Gatto L., Girke T. et al. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor. Nat. Methods. 2015; 12:115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grosswendt S., Filipchyk A., Manzano M., Klironomos F., Schilling M., Herzog M., Gottwein E., Rajewsky N.. Unambiguous identification of miRNA: target site interactions by different types of ligation reactions. Mol. Cell. 2014; 54:1042–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kozomara A., Griffiths-Jones S.. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 42:D68–D73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paraskevopoulou M.D., Georgakilas G., Kostoulas N., Vlachos I.S., Vergoulis T., Reczko M., Filippidis C., Dalamagas T., Hatzigeorgiou A.G.. DIANA-microT web server v5. 0: service integration into miRNA functional analysis workflows. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:W169–W173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paraskevopoulou M.D., Vlachos I.S., Karagkouni D., Georgakilas G., Kanellos I., Vergoulis T., Zagganas K., Tsanakas P., Floros E., Dalamagas T.. DIANA-LncBase v2: indexing microRNA targets on non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:D231–D238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vlachos I.S., Zagganas K., Paraskevopoulou M.D., Georgakilas G., Karagkouni D., Vergoulis T., Dalamagas T., Hatzigeorgiou A.G.. DIANA-miRPath v3. 0: deciphering microRNA function with experimental support. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:W460–W466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]